Prevention/treatment of metastasis represents the major challenge in cancer therapy today. In spite of a surge in research advances in the field, our understanding of the metastatic process is far from complete. There is much to be learned by looking back at previous failed attempt to develop anti-metastatic drugs;1–3 to ignore history is to repeat mistakes of the past.

The decade of the 1990’s was witness to a frenzy of activity in pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies to discover new forms of treatment for cancer. Enzymes that degrade the extracellular matrix (ECM) had long been viewed as essential for tumor progression. Moreover, it was thought that MMPs are upregulated in virtually all human and animal tumors and cell lines.1 MMPs, especially those capable of cleaving type IV basement membrane collagen (MMP-2 and -9) were considered to be ideal targets for drug development. Compelling preclinical data from many laboratories provided overwhelming support for a causal relationship between MMP overexpression and tumor invasion/metastasis. Based on these views, more than 50 MMP inhibitors have been pursued as clinical candidates. Peptide and peptide-like compounds were initially designed to target the chemical functional groups that chelate the active zinc (II) ion in the catalytic domain of MMPs. These drugs essentially mimicked the major collagen substrate of MMPs, and thereby work as competitive potent, reversible inhibitors of enzyme activity.3 Subsequently, MMP inhibitor design became more structure-base, due to the abundance of NMR and X-ray structural data.4

Initial non randomized clinical trials reporting impressive tumor regression, led to MMP inhibitors being tested in numerous Phase II–III trials involving thousands of patients with a variety of cancers (lung, stomach, colon, pancreas, ovary, breast, brain, prostate); unfortunately none of these trials provided positive results.1,3 Four caveats need to be emphasized about the lack of success of MMP inhibitor clinical trials to date: (1) due to extensive homology between catalytic domains of MMPs, none of the drugs were highly selective for specific MMPs; (2) entry criteria in these trials excluded patients with early stage cancer; (3) unanticipated long-term drug intolerance reduced drug compliance; (4) drug dosage based on short-term kinetic studies in healthy volunteers were not necessarily predictive of chronic therapeutic drug levels achieved in patients with cancer.5 Based on more recent studies, the lack of efficacy of broad-spectrum MMP inhibitors has been attributed to the following: (1) some MMPs display anti-tumor activities (MMP-8 and MMP-12). Hence, current recommendations favor development of MMP inhibitors directed at specific, well defined MMPs; (2) MMP inhibitors appear to be more active in early, rather than late stage cancer; (3) examination of MMP expression in human tumor tissue sections revealed that MMPs are largely produced by recruited reactive stromal cells, rather than the tumor cells themselves, hence the cellular target for protease inhibition needs to be more precisely defined;1,2,6 and (4) MMPs promote tumor progression not only through ECM degradation as originally thought, but also through cleavage of many non ECM proteins. MMPs counter apoptosis, orchestrate angiogenesis, regulate innate immunity, release growth factors bound to the ECM, and alter chemokines that affect cell migration. Today’s challenge is to distinguish the action of MMPs that contribute to tumor progression from those that are crucial for host defense, as blocking the latter will worsen clinical outcome.2

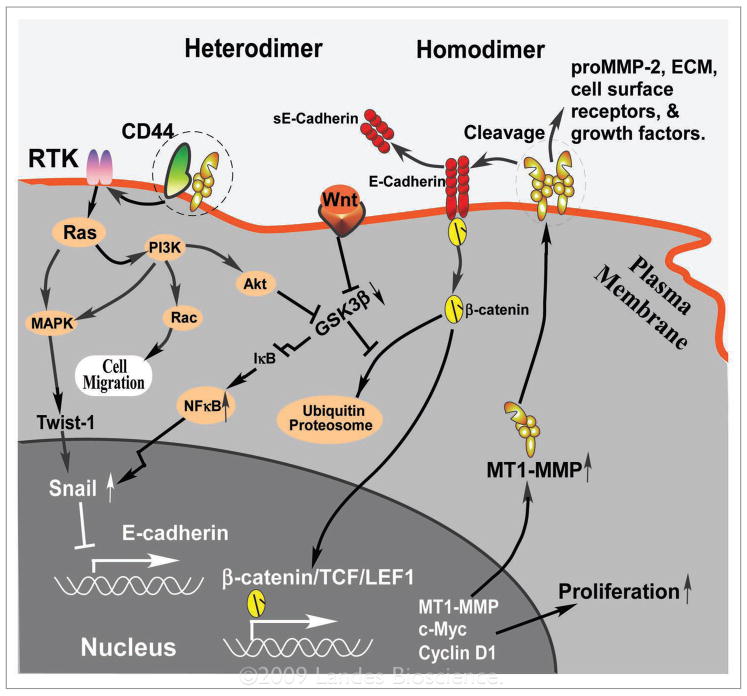

Since the discovery of cell surface-localized MMPs more than 20 years ago7 and the distinctive subfamily of membrane type (MT)-MMPs,8 a critical role has been recognized for MT1-MMP in cancer cell invasion through native type I collagen, leading to widespread cancer cell metastasis.9 Extensive cleavage of pericellular substrates by MT1-MMP, make it the most potent MMP. MT1-MMP is also involved in numerous intracellular signaling pathways (see Fig. 1).10–13 Hence, it comes as no surprise that discovery of specific inhibitors of MT1-MMP has become the Holy Grail in MMP inhibitor drug development. An alternative cancer concept proposes that total inhibition of MMPs leads to an efficient amoeboid mode of cell migration with rounded cell morphology with no obvious cell polarity, driven by actomyosin contractility, thereby negating the importance of MMPs in cancer dissemination.14,15 Although based on fascinating and intriguing in vitro experiments, the latter theory remains to be proven relevant to cancer.

Figure 1.

Hypothetical function of mT1-mmP homodimer and heterodimer formation on proteolytic activity, cell migration and proliferation: The hemopexin (PeX) domain of mT1-mmP interacts with CD44 or an unknown protein (heterodimer) at the cell surface, which signals for cell migration through maPK, PI3K and rac pathways,11 possibly involving initial activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (rTK) and ras. maPK also signals to the nucleus leading to epithelial-mesenchymal transition (emT) by enhancing Twist-1 and Snail activation.13 enhanced activity of PI3K or Wnt signaling pathways leads to inhibition of GSK-3β, an important regulator for β-catenin and Snail. Inhibition of GSK-3β results in transcriptional downregulation of IκB, and hence enhances activity of nFκB and subsequent Snail expression.12 mT1-mmP also forms homodimers at the cell surface which is critically important for the enzymatic activity of mT1-mmP. Cleavage of cell-cell adherens junction molecule, e-cadherin by mT1-mmP leads to dissociation of the e-cadherin-β-catenin complex and results in β-catenin relocation. β-catenin relocation to nucleus serves as a transcription factor along with TCF to upregulate gene expression for cell proliferation. Positive and negative feedback loops involving mT1-mmP and e-cadherin maintain the aggressive character of emT cancer cells. mT1-mmP also cleaves prommP-2, most of extracellular matrix (eCm) components, growth factors, and cell surface receptors. Both proteolytic activity and non-proteolytic activity of mT1-mmP coordinate to promote cancer emT. other control mechanisms for mT1-mmP function in cells involve enzyme activation by furin in the trans Golgi network and an elaborate endocytic pathway (not shown).

In this issue, Suojanen et al.16 describe the identification of a selective MT1-MMP cyclic peptide inhibitor GACFSIAHECGA (designated peptide G) derived by phage display, which did not affect the activities of 13 other MMPs. The activity of peptide G appears to be dependent on an intact disulfide bond and a structurally restrained conformation. Peptide G has an interesting history in that it was initially employed as a negative control in biological experiments in which other cyclic peptides were identified with inhibitory activity against MMP-2 and MMP-9.17 Relatively high concentrations (IC50 of 150–500 μM) of peptide G were required to inhibit the protease activity of MT1-MMP and reduce cancer cell migration and invasion in vitro. Growth of carcinoma xenografts in mice was also significantly (p < 0.04) inhibited by peptide G, but due to wide variation in tumor size, differences between treatment groups are not impressive. Suojanen et al.16 concluded that the anti-tumorigenic effect of peptide G in vivo is likely to be due to an effect on ECM remodeling and invasion of tumor cells, rather than anti-proliferative or anti-angiogenic effects.

Recently, Devy et al.18 have reported that a highly selective and potent (IC50 ~1–5 nM) fully human MT1-MMP inhibitory antibody markedly slowed tumor progression/metastasis and inhibited angiogenesis in mice with xenogenic human cancer implants. This antibody apparently reacts only with activated MT1-MMP, not the latent enzyme (personal communication). Concurrent administration of MT1-MMP antibody and paclitaxel chemotherapy or MT1-MMP antibody and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody resulted in additive anti-tumor activity. Commercial development of this antibody has been initiated with the goal of clinical trial(s) in cancer.

This brings up important issues regarding planning a clinical trial of an MMP inhibitor in cancer. When is preclinical data sufficiently compelling to enter a drug into clinical trials and what trial design should be employed? Owing to imperfect preclinical models that invariably overestimate clinical activity, the first part of the question can’t be easily answered. Based on discovery of biologic agents with molecularly targeted activity in selected subtypes of cancer e.g., traztuzumab (herceptin) in HER-2/Neu positive breast cancer, it has become clear that new methods need to be established to identify the subpopulation of cancer patients more likely to benefit from drugs directed at specific pathways. As an example, testing of traztuzumab exclusively in breast cancers lacking HER-2/Neu expression (the majority of patients) would have resulted in discarding this valuable drug.19

Approaches to identify patients likely to respond to specific MT1-MMP inhibitory drugs include: immunohistochemistry of patient tumor tissue, blood levels of MT1-MMP or its’ breakdown products or cleaved substrates, surrogate tumor markers, and in vivo optical imaging techniques to identify “hot spots” of MT1-MMP protease activity.20 Even a technique as well developed as immunohistochemistry for MT1-MMP in tumor tissue is fraught with discrepant results in the literature. Furthermore, there still is uncertainty as to whether the protease is produced by the cancer cells or stromal cells within a tumor. Going back to the example of HER-2/Neu overexpression in breast tumors, major problems in standardization of techniques still persist even a decade after introduction of the test.19

To conclude, pharmacologic inhibitors of MT1-MMP including peptide G and the human antibody to MT1-MMP have a long way to go before being ready for “prime time”. But there is reason to be optimistic that specific MMP inhibitors will find a place in the treatment of selected cancers. Based on the “flop” of broad-spectrum MMP inhibitors in the 1990’s, the reluctance of “big pharma” to invest in new MMP inhibitors will need to be overcome by thorough preclinical studies addressing the uncertainties described above.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cbt/article/10139

Commentary to: Suojanen J, Salo T, Koivunen E, Sorsa T, Pirila E. A novel and selective membrane type-I matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) inhibitor reduces cancer cell motility and tumor growth. Cancer Biol Ther 2009; This issue.

References

- 1.Coussens L, Fingleton B, Matrisian L. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors and cancer: Trials and tribulations. Science. 2002;295:2387–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1067100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Overall CM, Kleifeld O. Validating matrix metalloproteinases as drug targets and anti-targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:227–39. doi: 10.1038/nrc1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zucker S, Cao J, Chen W-T. Critical appraisal of the use of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors in cancer treatment. Oncogene. 2001;19:6642–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puerta DT, Cohen SM. A bioinorganic perspective on matrix metalloproteinase inhibition. Curr Topics Medicinal Chem. 2004:4. doi: 10.2174/1568026043387368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sparano JA, Bernardo P, Stephenson P, Gradishar WJ, Ingle JN, Zucker S, et al. Randomized phase III trial of marimastat versus placebo in patients with metastatic breast cancer who have responding or stable disease after first-line chemotherapy: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial E2196. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4631–38. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pavlaki M, Zucker S. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors (MMPIs): The beginning of phase I or the termination of phase III clinical trials. Cancer Metastasis Reviews. 2003;22:177–203. doi: 10.1023/a:1023047431869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zucker S, Lysik RM, Wieman J, Wilkie D, Lane B. Diversity of human pancreatic cancer cell proteinases. Role of cell membrane metalloproteinases in collagenolysis and cytolysis. Cancer Res. 1985;45:6168–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato H, Takino T, Okada Y, Cao J, Shinagawa A, Yamamoto E, et al. A matrix metalloproteinase expressed on the surface of invasive tumor cells. Nature. 1994;370:61–5. doi: 10.1038/370061a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hotary KB, Allen ED, Brooks PC, Datta NS, Long MW, Weiss SJ. Membrane type I matrix metalloproteinase usurps tumor growth control imposed by the three-dimensional extracellular matrix. Cell. 2003;114:33–45. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00513-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Itoh Y, Seiki M. MT1-MMP: A potent modifier of pericellular microenvironment. J Cell Physiol. 2006;206:1–8. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munshi HG, Wu Y, Mukhopadhvay S, Ottaviano AJ, Sassano A, Koblinski JE, et al. Differential regulation of membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase activity by ERK 1/2 and p38 MAPK-modulated tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 2 expression control transforming growth factor-beta1-induced pericellular collagenolysis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39042–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404958200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma M, Chuang W, Sun Z. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT stimulates androgen pathway through GSK3beta inhibtion and nuclear beta-catenin accumulation. J Biol Chem. 2002;272:30935–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201919200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smit MA, Geiger TR, Song JY, Gitelman I, Peeper DS. A twist-snail axis critical for TrkB-induced epithelial-mesenchymal trasition-like formation, anoikis resistance and metastasis. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3722–37. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01164-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanz-Moreno V, Gadea G, Ahn J, Paterson H, Marra P, Pinner S, et al. Rac activation and inactivation control plasticity of tumor cell movement. Cell. 2008;135:510–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolf K, Mazo I, Leung H, Engelke K, Von Andrian UH, Deryunina EI, et al. Compensation mechanism in tumor cell migration: mesenchymal-amoeboid transition after blocking of pericellular proteolysis. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:267–77. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200209006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suojanen J, Salo T, Koivunen E, Sorsa T, Pirila E. A novel and selective membrane type-I matrix meatalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) inhibitor reduces cancer cell motility and tumor growth. Cancer Biology Therapy. 2009 doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.24.10139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koivunen E, Arap W, Valtanen H, Rainisalo A, Medina OP, Heikkila P, et al. Tumor targeting with a selective gelatinase inhibitor. Nature Biotechnol. 1999;17:768–74. doi: 10.1038/11703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devy L, Huang L, Noa L, Yanamandra N, Pieteters H, Frans N, et al. Selective inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-14 blocks tumor growth, invasion and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1517–24. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robert N, Leyland-Jones B, Asmar L, Belt R, Ilegbodu D, Loesch D, et al. Randomized phase III study of traztuzumab, paclitaxel and carboplatin compared with traztuzumab and paclitaxel in women with HER-2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;20:2786–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McIntyre JO, Matrisian LM. Optical proteolytic beacons for in vivo detection of matrix metalloproteinase activity. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;539:155–74. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-003-8_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]