Abstract

Oncolytic virotherapy makes use of the natural ability of viruses to infect and kill cancer cells. Adenovirus serotype 5 (Ad5) has been approved for use in humans as a therapy for solid cancers. In this study, we have tested whether Ad5 and low-seroprevalence adenoviruses can be used as oncolytics for multiple myeloma (MM). We show that Ad5 productively infects most myeloma cell lines, replicates to various degrees, and mediates oncolytic cell killing in vitro and in vivo. Comparison of Ad5 with low-seroprevalence Ads on primary marrow samples from MM patients revealed striking differences in the abilities of different adenoviral serotypes to kill normal CD138– cells and CD138+ MM cells. Ad5 and Ad6 from species C and Ad26 and Ad48 from species D all mediated killing of CD138+ cells with low-level killing of CD138– cells. In contrast, Ad11, Ad35, Ad40, and Ad41 mediated weak oncolytic effects in all of the cells. Comparison of cell binding, cell entry, and replication revealed that Ad11 and Ad35 bound MM cells 10 to 100 times better than other serotypes. However, after this efficient interaction, Ad11 and Ad35 viral DNA was not replicated and cell killing did not occur. In contrast, Ad5, Ad6, Ad26, and Ad48 all replicated 10- to 100-fold in MM cells and this correlated with cell killing. These data suggest that Ad5 and other low-seroprevalence adenoviruses may have utility as oncolytic agents against MM and other hematologic malignancies.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a disorder of B lymphocyte lineage cells resulting in clonal expansion of plasma cells in the bone marrow, overproduction of monoclonal immunoglobulin, and bone destruction (Kyle and Rajkumar, 2008). Current treatment protocols involve chemotherapy with bone marrow transplantation or treatment with melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide (Kyle and Rajkumar, 2008). Although these treatments have efficacy, patients have median survivals of 2 to 5 years.

Oncolytic virotherapy is an alternative cancer therapy in which a virus is used to selectively kill cancer cells while sparing normal cells (Cattaneo et al., 2008). This approach is attractive, because it is self-amplifying and each virus that enters and kills a cancer cell can produce thousands of progeny virions that can also kill more malignant cells. Measles virus, vaccinia virus, reovirus, and coxsackievirus A21 have been tested as oncolytic agents for MM (Peng et al., 2003; Ong et al., 2006; Haralambieva et al., 2007; Thirukkumaran et al., 2003; Lichty et al., 2004; Au et al., 2007).

Adenovirus serotype 5 (Ad5) became the first oncolytic virus to be approved for clinical use in humans in solid tumors (Liu et al., 2007). In vitro, Ad5 infects cells via its fiber and penton base proteins by binding the coxsackievirus–adenovirus receptor (CAR) (Bergelson et al., 1997) and αv integrins (Wickham et al., 1993). Given that most hematologic cells do not express high levels of these receptors, Ad5 has not generally been considered as an oncolytic agent for malignancies such as MM. In this work, we show that Ad5 can infect and kill most myeloma cell lines and patient samples as evidenced by reporter gene expression, viral DNA replication, viral titering, and cell death assays. We then compared cell killing of patient MM samples by viruses from species B, C, D, and F and show that Ad5, Ad6, Ad26, and Ad48 have the ability to kill patient MM cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

Myeloma cell lines ALMC-1, ALMC-2 (Arendt et al., 2008), and ANBL-6 (Jelinek et al., 1993) were maintained in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) plus Glutamax supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone, Logan, UT), interleukin (IL)-6, and epidermal growth factor (EGF). All other myeloma cell lines were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS. Human embryonic kidney cells (HEK 293) were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS. Human lung carcinoma A549 (American Type Culture Collection [ATCC], Manassas, VA) was maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS.

Patient samples

Myeloma cell samples were collected at the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN) from the bone marrow of patients after informed consent and institutional review board approval had been obtained. CD138– and CD138+ MM cells were separated with StemSep CD138 cocktail/colloid and a positive selection program on a RoboSep separator (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada). Patient cells were maintained in culture with IMDM plus Glutamax supplemented with 10% FBS.

Viruses

Ad5-GL-RC is a replication-competent Ad5 virus that expresses the green fluorescent protein (GFP)–luciferase fusion gene under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter by insertion of this cassette between E1a and E1b (Shashkova et al., 2008). Ad-GL-RC has the immunomodulatory E3 genes deleted, but overexpresses the adenoviral death protein (ADP; E3-11.6K) for improved viral spread (Doronin et al., 2000). Ad5-GL-RC particles were generated as described in our reference (Shashkova et al., 2008). Ad5, Ad6, Ad11, Ad26, Ad40, Ad41, and Ad48 were obtained from the ATCC. Viruses were purified by CsCl purification and quantitated by determining the optical density at 260 nm (OD260).

Analysis of in vitro infection and killing

MM cells were infected with the indicated viral particles (VP) per cell for the indicated amounts of time at 37°C. In some cases, cells were trypsinized and washed to remove virions that were not internalized. Cells were then plated and incubated at 37°C for the indicated times before imaging by fluorescence microscopy. Loss of membrane integrity was assessed by trypan blue uptake as described by Barry and colleagues (1990).

Analysis of viral DNA replication by real-time polymerase chain reaction

Cells infected with Ad-GL-RC or wild-type adenovirus were collected and DNA was purified with a DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed with primers against a 150-base pair region of the hexon gene as described in Hofherr and colleagues (2008). For wild-type adenovirus, real-time PCR was performed with adenoviral species-specific primers (species C: forward primer, TTCGATGATGCCGCAGTGGTCTTACATGCAC; reverse primer, TTTCTAAACTTGTTATTCAGGCTGAAGTACG; species B: forward primer, ATCGATGCTGCCCCAATGGGCATACATGCAC; reverse primer, AGATTGAAGTAGGTGTCTGTGGCGCGGGC; species D: forward primer, ACCGCCAGAGAACGCGCGAAGATGGCCACCC; reverse primer, AGGCTGAAGTACGTGTCGGTGGCGCGGGC).

Analysis of viral progeny production

At the indicated times, cells and media were collected and frozen at −80°C. Each sample was freeze–thawed three times and mixed, and 10 μl was diluted in medium by serial dilution from 10–2 to 10–12. Dilutions were plated on a 24-well plate seeded with A549 cells. Forty-eight hours after infection, the cells were fixed and titering was performed with an Adeno-X rapid titer kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). Titer values were expressed as infectious units (IFU)/ml and calculated according to the following formula:

|

Animals

All animal experiments were carried out according to the provisions of the Animal Welfare Act, Public Health Service Animal Welfare Policy, the principles of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and the policies and procedures of Mayo Clinic. Female nonobese diabetic-severe compromised immunodeficient (NOD-SCID) mice (4–6 weeks old) were purchased from Harlan Sprague-Dawley (Indianapolis, IN).

ALMC-2 tumor model

ALMC-2 tumors were established by subcutaneous injection of 5 × 106 cells in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 50% Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) into the hind flank of NOD-SCID mice. When tumors were measurable (6 to 10 weeks after cell injection), mice were injected intratumorally with 3 × 1010 VP of Ad5-GL-RC in 100 μl of PBS. Tumor dimensions were measured at regular time points after virus injection as described by Doronin and colleagues (2000). Mice were killed when tumor volume represented 10% of mouse size.

Results

Infection of MM cell lines by Ad5

Previous studies showed that Ad5 can infect myeloma cells (Wattel et al., 1996; Meeker et al., 1997; Teoh et al., 1998), but that replication by the virus is markedly delayed (Lavery et al., 1987; Lavery and Chen-Kiang, 1990). This suggested that oncolytic Ad5 might be able to kill MM cells, but with a slower kinetic than in solid tumors. To test this, MM cell lines were infected with the replication-competent Ad5 vector Ad5-GL-RC (Shashkova et al., 2008), which expresses a green fluorescent protein–luciferase fusion protein. ALMC-1 and ALMC-2 cell lines were tested, because they represent patient samples at different stages of neoplasia (Arendt et al., 2008). ALMC-1 cells were isolated from a patient diagnosed with primary amyloidosis. ALMC-2 cells were isolated from the same patient after they relapsed with frank MM symptoms (Arendt et al., 2008).

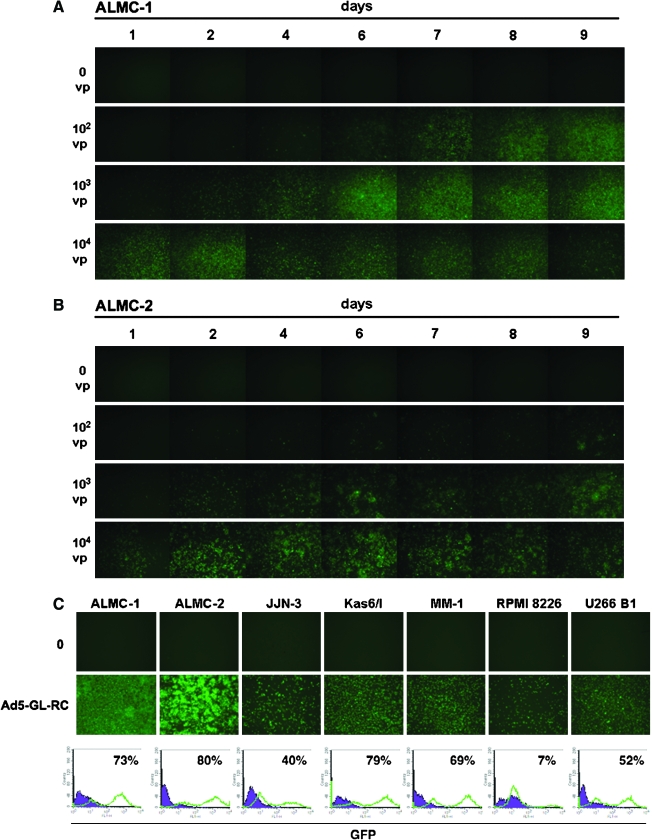

ALMC-1 and ALMC-2 cells were incubated with 0, 100, 1000, and 10,000 VP/cell of Ad5-GL-RC and GFP expression was monitored by fluorescence microscopy for 9 days after infection (Fig. 1). Both cell lines were productively infected with Ad5, consistent with previous observations in other MM cell lines (Wattel et al., 1996; Meeker et al., 1997; Teoh et al., 1998). At MOIs from 1000 to 10,000 VP/cell (20 to 200 plaque-forming units [PFU]/cell), GFP expression peaked within 2 to 3 days in both cell lines. At a lower MOI of 100 VP/cell (2 PFU/cell), the GFP signal did not maximize until 6 to 7 days after infection. This suggested that the replication-competent virus was infecting a subset of cells at this MOI and then spread through the cell population over 7 days. In both cell lines, GFP expression gradually diminished over time, suggesting that the virus might ultimately be killing the cells.

FIG. 1.

Expression of Coxsackievirus–Adenovirus Receptor in Multiple Myeloma Cell Lines

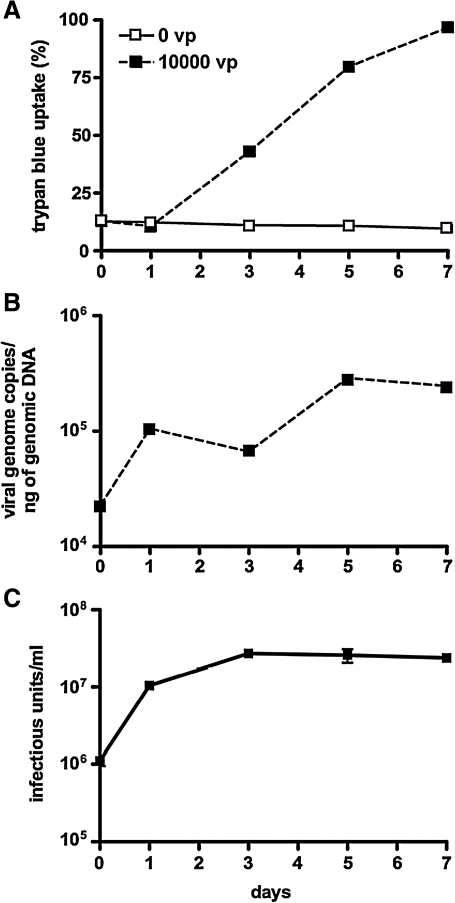

To test this, ALMC-2 cells were infected with Ad-GL-RC and stained with trypan blue to assess loss of membrane integrity over time (Fig. 2A). In this case, infection with 10,000 VP/cell produced increasing trypan blue uptake over 7 days. ALMC-2 cells were next incubated with Ad-GL-RC for 1 hr and then were treated with trypsin to remove virions that had not internalized. Cells and their supernatants were collected over 7 days and DNA was extracted from the samples for real-time PCR against the hexon gene to quantitate viral genome copies (Fig. 2B). PCR of samples demonstrated that viral genome copies increased 15-fold over 7 days after a short (1-hr) infection with the replication-competent virus. Production of progeny virions from ALMC-2 cells was assessed by infecting the cells for 1 hr with Ad-GL-RC, washing with trypsin, and then assaying for infectious units from the cells and supernatants at various times (Fig. 2C). In this assay, viral titers increased approximately 30-fold over 3 days after infection. These data indicate that Ad5 replicates and produces progeny virions during the course of killing ALMC-2 cells.

FIG. 2.

Expression of Coxsackievirus–Adenovirus Receptor in Multiple Myeloma Cell Lines

To test whether Ad5 could infect a variety of MM cells, additional MM cell lines including ALMC-2, JJN-3, KAS-6/1, MM-1, RPMI 8226, and U266B1 were infected with Ad5-GL-RC and the cells were observed by fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry. Each of the MM cell lines was productively infected as indicated by the presence of GFP-positive cells ranging from 7 to 80% (Fig. 1C). When MM cell lines were evaluated by flow cytometry for expression of the coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR), 60 to 97% of the cells expressed the Ad5 receptor (Table 1), consistent with the general ability of the virus to infect the cells.

Table 1.

Expression of Coxsackievirus–Adenovirus Receptor in Multiple Myeloma Cell Lines

| |

CAR expression |

CD46 expression |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell line | PE positive (%) | MFI | PE positive (%) | MFI |

| AMLC-1 | 60.90 | 9.17 | 94.27 | 16.27 |

| AMLC-2 | 90.94 | 18.46 | 99.58 | 23.57 |

| Kas I | 78.88 | 14.80 | 98.69 | 93.43 |

| RPMI 8226 | 95.80 | 35.27 | 99.84 | 107.13 |

| U266 B1 | 97.67 | 21.44 | 100.00 | 109.14 |

Abbreviations: CAR, coxsackievirus–adenovirus receptor; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; PE positive, percentage positive cells observed after staining with unlabeled CAR or CD46 antibody followed by phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled secondary antibody.

Treatment of ALMC-2 tumor xenografts with oncolytic Ad5

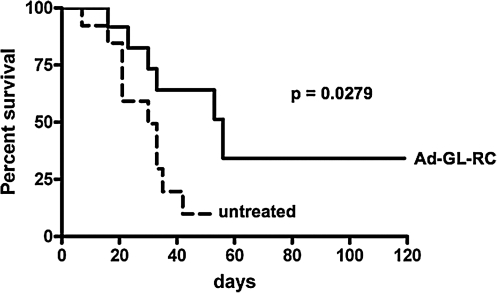

These data suggested that Ad5-GL-RC was able to infect and amplify in multiple myeloma cancer cell lines in vitro. To test the virus in vivo, subcutaneous ALMC-2 tumors were initiated in NOD-SCID mice. In this model, tumors form asynchronously, so mice were either untreated or injected with virus when tumors reached 200 mm3 in size, which occurred at various times after tumor initiation (Fig. 3). When Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated, comparison of the two groups by log-rank analysis demonstrated that Ad5 mediated a statistically significant reduction in death due to tumor growth (p = 0.0279). These data suggest that Ad5 is able to infect, replicate in, and kill MM cells in vivo.

FIG. 3.

In vivo treatment of ALMC-2 cell line tumors with oncolytic adenovirus. Tumors were initiated in mice, which were then either left untreated or treated at such times when the tumors reached 200 mm3 in size. Each mouse was injected intratumorally with 3 × 1010 viral particles of replication-competent Ad5-GL-RC. Mice were killed when tumors exceeded 10% of mouse weight. Results are represented by a Kaplan–Meier survival curve comparing untreated and Ad5-treated mice. Log-rank statistical comparison was applied, demonstrating p = 0.0279.

Ad5 infection, replication, and killing of patient MM cells

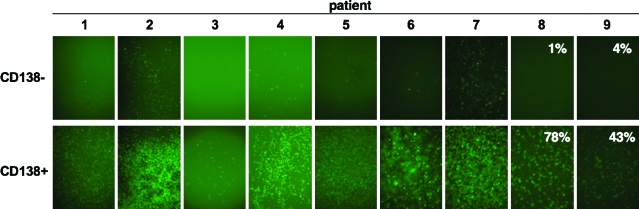

Cell lines are immortalized and can sometimes support the growth of viruses because of this transformation. Given this, we next tested the ability of Ad5-GL-RC to infect primary cells isolated from bone marrow samples from MM patients. MM cells home to the bone marrow. Within bone marrow samples, MM cells can be identified by their expression of the marker CD138. To test Ad5 versus primary samples, CD138– normal marrow cells and CD138+ MM cells were tested. In this case, patient cells were incubated for 1 hr with Ad5 and then were washed and treated with trypsin to remove virions from the surface of the cells. This removes virions that have not internalized, allowing kinetic comparisons of viral replication to be compared with transduction and cell-killing data. Two days after infection, GFP-positive cells were observed in all patient cells after infection, with markedly higher infection of CD138+ MM cells than CD138– normal marrow cells (Fig. 4). Flow cytometry was performed on CD138– and CD138+ cells from the last two patients. For CD138+ cells, Ad5-GL-RC produced 11 to 28% GFP-positive cells when exposed to an MOI of 1000 VP/cell (20 PFU/cell) (data not shown) and 42 to 78% GFP-positive cells at an MOI of 10,000 VP/cell (200 PFU/cell). For CD138– cells, there were 1 to 4% GFP-positive cells in both patients at either MOI.

FIG. 4.

Infection of primary cells from MM patients. CD138– and CD138+ samples from the bone marrow of MM patients were treated with Ad5-GL-RC at 10,000 VP/cell (200 PFU/cell) for 1 hr and were washed with trypsin to remove virions that had not entered the cells. GFP expression is shown for each sample 5 days after infection. Flow cytometry was performed on patient 8 and 9 cells and the GFP-positive cell numbers are shown in each panel. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/hum.

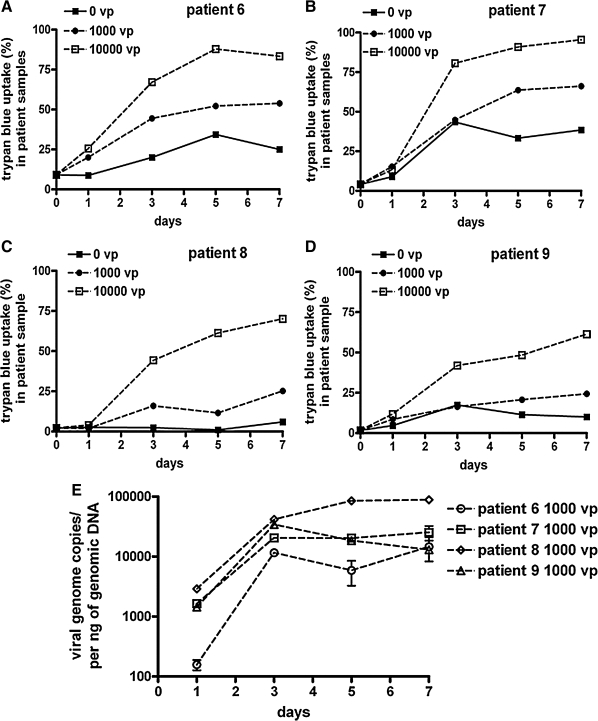

MM cells and their supernatants from four patients were collected at various times after 1 hr of Ad5 infection to measure cell death and viral DNA replication. Loss of membrane integrity was assayed by trypan blue uptake. This assay demonstrated that a short (1-hr) infection of the MM cells with 1000 or 10,000 VP/cell (20 to 200 PFU/cell) produced detectable cell killing within 7 days in all the patient samples (Fig. 5). Real-time PCR was performed at the same time points to assay changes in viral genome copies in the cells. PCR of the 1000-VP/cell (20-PFU/cell) samples with hexon-specific primers demonstrated that genome copies increased 10- to 40-fold over 7 days (Fig. 5E), indicating that Ad5 is replicating its genome in these primary MM cells.

FIG. 5.

Replication and cell killing by Ad5 in patient MM cells. The indicated CD138+ samples from the bone marrow of MM patients were treated with Ad5-GL-RC at 10,000 VP/cell (200 PFU/cell) for 1 hr and were then washed with trypsin to remove virions that had not entered the cells. (A–D) Trypan blue uptake of Ad5-infected cells. At the indicated time points, samples of infected cells were analyzed for loss of membrane integrity with trypan blue. (E) Viral genome levels. Samples from the 1000-VP/cell infections in (A) were analyzed for viral genome copy numbers by real-time PCR on the indicated days. Samples infected with 10,000 VP/cell showed similar results with higher initial genome copies (data not shown).

Screening alternative adenoviral serotypes as oncolytics

Testing with GFP-expressing Ad5-GL-RC showed that the virus infects MM cell lines and cells, particularly at higher MOIs. To test whether adenoviruses using other receptors might have better efficacy against MM, we compared the ability of wild-type Ad5 to kill MM cells versus other wild-type adenoviral serotypes including Ad6, Ad11, Ad35, Ad26, and Ad48. Ad5 and Ad6 are species C viruses that both use the coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR). Therefore, Ad6 should kill MM cells to a similar extent as Ad5. Ad11 and Ad35 are species B viruses that use CD46 protein as a receptor. Because CD46 is ubiquitously expressed on human cells and MM cells (Table 1), these viruses might have a better capacity to infect MM cells. Ad26 and Ad48 are species D viruses that may use a mix of CAR, CD46, and sialic acid for cell binding and infection. These viruses therefore might also have a better or equal potential to infect MM cells compared with Ad5. These wild-type adenoviral serotypes were compared with species F Ad40 and Ad41. These viruses use the CAR, but are “fastidious” and unlikely to act as oncolytics, thus representing likely negative control viruses.

Ad6, Ad11, Ad26, Ad35, and Ad48 were also selected for testing, because these have lower seroprevalence in humans compared with Ad5. Twenty-seven to 50% of humans have neutralizing antibodies against Ad5 (Piedra et al., 1998; Thorner et al., 2006). Therefore, patients treated with oncolytic Ad5 may experience reduced viral efficacy due to neutralization of the virus. In contrast, less than 10% of humans have preexisting immunity to Ad6, Ad11, Ad26, and Ad48 (Piedra et al., 1998; Thorner et al., 2006), making these less likely to be neutralized in immune-competent patients.

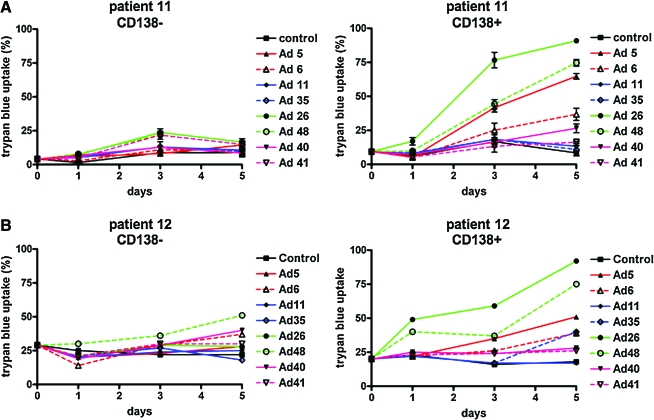

To test the utility of the various adenoviral serotypes, CD138– and CD138+ marrow cells from two patients were incubated for 1 hr with each of the viruses. Because these viruses do not express GFP, their oncolytic activity was assessed by trypan blue staining (Fig. 6). Interestingly, Ad26 and Ad48 produced the highest CD138+ cell killing, with Ad5 next in efficacy. In contrast, Ad11 and Ad35 were surprisingly ineffective on both of the patients' cells. Interestingly, Ad6 was not as effective as Ad5, despite both being from the same species.

FIG. 6.

Comparison of MM cell killing by alternative adenoviral serotypes. CD138– and CD138+ samples from the bone marrow of MM patients (A, patient 11; B, patient 12) were treated for 1 hr with the indicated adenoviral serotypes at 10,000 VP/cell, and trypan blue staining was performed on the indicated days to assess loss of membrane integrity. These viruses do not express reporter genes, and therefore trypan blue uptake was used to assess infectivity and cell killing. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/hum.

MM cell binding, entry, and replication by various adenoviral serotypes

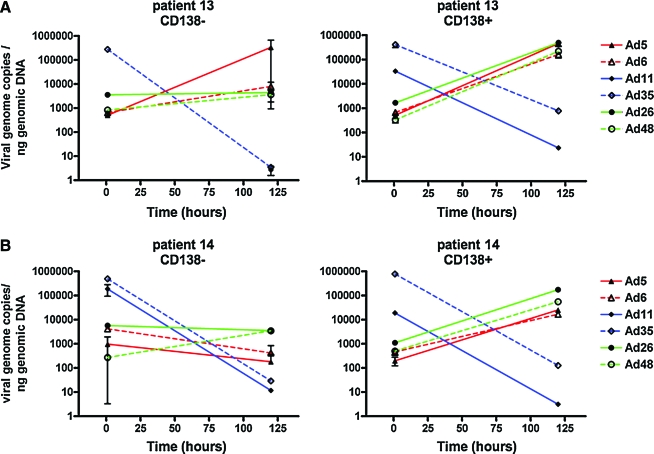

To test whether the differences in cell killing were related to viral binding, entry, and replication, two additional primary marrow samples were tested. Each virus was incubated for 1 hr at 4°C at an MOI of 10,000 VP/cell (200 PFU/cell) to allow viral binding and a sample of each was collected for PCR. The remaining cultures were then shifted to 37°C for 1 hr, the cells were washed in trypsin to remove all noninternalized virions, and a sample was collected. The remaining culture was then incubated for 5 days in medium before PCR to quantitate whether viral genome copies increased over time (intermediate time points were not collected, because only a limited number of cells was available from each patient). Each sample was then processed and real-time PCR was performed with species-specific oligonucleotides to quantitate viral genomes at each time point (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Comparison of adenoviral serotype cell binding, entry, and replication in CD138– and CD138+ marrow cells. CD138– and CD138+ samples from the bone marrow of MM patients (A, patient 13; B, patient 14) were treated with the indicated adenoviral serotypes at 10,000 VP/cell for 1 hr at 4°C at an MOI of 10,000 VP/cell and then were shifted to 37°C for 1 hr. The cells were then washed in trypsin to remove all noninternalized virions, and samples were collected. The remaining cultures were then incubated for 5 days in medium and samples were collected. Each sample was subjected to real-time PCR with species-specific oligonucleotides to quantitate viral genomes at each time point. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/hum.

After 1 hr of binding at 4°C, PCR demonstrated that Ad11 and Ad35 bound to both CD138– and CD138+ marrow cells 3- to 100-fold better than did Ad5, Ad6, Ad26, or Ad48 (Fig. 7). For all of the viruses, there was no obvious difference in binding between CD138– and CD138+ cells. Subsequent incubation for 1 hr at 37°C to allow viral internalization reduced the number of cell-associated genome copies approximately 10-fold for all of the viruses. Real-time PCR, performed on the cells after 5 days (120 hr) of infection, showed an interesting difference between the viruses. On CD138+ cells, Ad5, Ad6, Ad26, and Ad48 viral genome copies increased 10- to 100-fold, indicating the viruses had replicated. In marked contrast, Ad11 and Ad35 genome copies decreased 1000- to 10,000-fold in the CD138+ cells over the same time period. On CD138– normal cells, all viral genomes decreased over 5 days, with the exception of Ad5 on patient 13, in whom genome copies increased. This was not observed in patient 14, suggesting some variation from patient to patient. These data suggest that Ad5, Ad6, Ad26, and Ad48 bind to MM cells less efficiently than do Ad11 and Ad35. However, only Ad5, Ad6, Ad26, and Ad48 replicate their genomes in the MM cells and this replication correlates with the ability of these viruses to kill MM cells. Ad11 and Ad35 did not appear to replicate in MM cells and this inability correlated with their low-level oncolytic activity in the cells. These data suggest that Ad5, Ad6, Ad26, and Ad48 may have utility as oncolytic viruses for MM.

Discussion

This work shows that Ad5, Ad6, Ad26, and Ad48 can infect and kill MM cells. Ad5 uses the CAR and αv integrins for infection in vitro. Previous work showed that replication-defective Ad5 can deliver genes into MM cell lines for gene therapy approaches (Teoh et al., 1998), but did not test primary MM cells from patients. Our data show that most MM cell lines and primary patient samples are productively infected by Ad5. Interestingly, oncolytic Ad5 appeared to infect CD138+ MM cells 10- to 70-fold more efficiently than normal marrow cells. This innate specificity can likely be enhanced by applying transcriptional or replication targeting to oncolytic Ad5 to restrict its replication to MM cells. For example, B cell-specific promoters could be used to restrict expression of E1 or E4 to MM cells to spare other tissues, such as the liver, from Ad5 killing (reviewed in Cattaneo et al., 2008).

Previous work with wild-type Ad5 showed that the virus infects MM cell lines, but that its life cycle is delayed compared with that of permissive cells (Lavery et al., 1987). This is consistent with our observations of up to 30-fold increases in Ad5 genomes and progeny virions that occurred during cell killing over 7 days. This slow or low-level replication appears to be related to repression of E1 transcripts in MM cells (Lavery et al., 1987; Lavery and Chen-Kiang, 1990). This suggests that modifying E1 transcripts to evade this destabilization will enhance the efficacy of oncolytic adenovirus in MM. Even without optimization, Ad5 effectively kills primary MM cells.

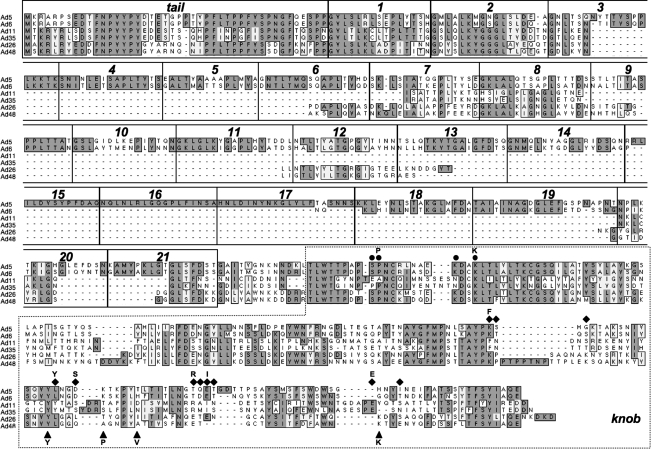

Given that many humans have neutralizing antibodies against Ad5, we tested whether other adenoviral serotypes with lower seroprevalence might also be able to kill patient MM cells. We show that Ad6, Ad26, and Ad48 all appear able to kill CD138+ cells while sparing CD138– cells. In contrast, Ad11 and Ad35 have weak activity. Ad6, like Ad5, uses the CAR as a receptor, but is missing shaft repeats 15, 16, and 17 and so has 18 repeats instead of the 21 repeats in Ad5 (Fig. 8). This shorter fiber protein may explain the lower activity of Ad6 on MM cells compared with Ad5. Ad26 and Ad48 are both species D viruses with low seroprevalence (Thorner et al., 2006). Although they are of the same species, they appear to use different receptors in vitro. Ad26 uses CD46, but not the CAR (Abbink et al., 2007). In contrast, Ad48 does not use the CAR and CD46 (Abbink et al., 2007). Ad26 and Ad48 fibers both display some, but not all, of the amino acids involved in sialic acid binding (Seiradake et al., 2009) (Fig. 8), suggesting that Ad26 and Ad48 may also use ubiquitous sialic acid as a receptor. Given that Ad11 and Ad35 did not kill MM cells, but that Ad26 and Ad48 did, it is possible that Ad26 and Ad48 may be entering the cells via a non-CD46 pathway. Alternatively, differences in viral biology postentry could control oncolysis by Ad5, Ad26, and Ad48 and may underpin the differences in cell killing by different viruses.

FIG. 8.

Alignment of fiber proteins from adenoviral serotypes used in this study. The indicated adenoviral proteins were aligned with ClustalW (MacVector, Cary, NC). Identical amino acids are boxed in dark gray. Similar amino acids are boxed in light gray. Ad5 fiber tail, shaft β-spiral repeats, and knob domains are shown in boxes on the alignment, and are based on van Raaij and colleagues (1999). Residues in Ad5 and Ad6 that are likely involved in CAR binding are shown as circles above the sequence, and are based on Roelvink and colleagues (1999), Martin and colleagues (2003), and Jakubczak and colleagues (2001). Residues implicated in Ad11 and Ad35 CD46 binding are shown as diamonds, and are based on Wang and colleagues (2007) and Persson and colleagues (2007, 2009). Potential sialic acid binding residues for Ad26 and Ad48, shown as triangles, are based on Ad37 sialic acid binding motifs from Seiradake and colleagues (2009) and Burmeister and colleagues (2004). Letters above symbols indicate conserved residues.

Testing viral interactions with primary MM cells by real-time PCR suggests some explanations for the differing oncolytic effects of the viruses. Ad5, Ad6, Ad26, and Ad48 bound substantially less well to MM cells, but were able to replicate 10- to 100-fold in the cells over 5 days. In contrast, Ad11 and Ad35 bound much better to the cells, but their DNA was not replicated and declined over time. This failure to replicate correlated well with the inability of Ad11 and Ad35 to kill MM cells. These data suggest that the CD46 interaction may lead to less productive infection of MM cells, perhaps because of poor trafficking after entry. This is consistent with previous work showing that Ad5 vectors bearing the CD46-binding Ad35 knob resulted in lower infection efficiency because the majority of viral particles were trapped in late endosomal compartments or were recycled back to the cell surface (Shayakhmetov et al., 2003). Because Ad26 can also bind CD46, this suggests that either this virus is still effective because it uses an alternative receptor or that CD46 interactions with Ad26 do not lead to unproductive trafficking as with Ad11 and Ad35. Ad11, Ad35, Ad26, and Ad48 all have shorter fibers than Ad5 (i.e., 7 and 8 shaft repeats rather than 21; Fig. 8). Therefore short fiber shaft length does not appear important in determining productive MM cell infection and killing.

MM cells express both CAR and CD46 (Table 1) and are expected to display sialic acid. Although most of the cells express both receptors, it is notable that the per-cell levels of the two receptors (as assessed by mean fluorescence intensity [MFI]) is up to 10-fold lower for CAR than CD46 (Table 1). This suggests that lower CAR density may explain the reduced cell binding by Ad5 and Ad6 relative to Ad11 and Ad35. The affinity of viral binding to sialic acid is generally lower than interactions with CD46 or the CAR (Seiradake et al., 2009). It is therefore possible that the lower binding of Ad26 and Ad48 versus Ad11 and Ad35 may reflect this difference in affinity. It is possible that replacement of the fibers from Ad5, Ad6, Ad26, or Ad48 fibers with short- or long-shafted fibers from Ad11 or Ad35 may increase both binding and oncolysis by these already potent viruses. Conversely, if the CD46 interaction is a “dead end” for the viruses in MM, then such a fiber swap might actually reduce virus oncolysis.

We have compared the oncolytic activity of Ad5, Ad6, Ad11, Ad35, Ad26, and Ad48 in solid cancers (Shashkova et al., 2009; and our unpublished data). In prostate, breast, ovarian, and hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines, Ad5, Ad6, Ad11, and Ad35 were generally effective in vitro whereas Ad26 and Ad48 we less active. This is particularly interesting given the higher activity of Ad26 and Ad48 in MM. These data suggest that different adenoviral serotypes may have fundamentally different biologies in different cell types and this may translate into different efficacies against different types of cancers. When Ad5, Ad6, Ad11, and Ad35 were tested in vivo against prostate tumor xenografts in mice Ad5, Ad6, and Ad11 were effective, with Ad35 having lower activity. This was true after a single intratumoral injection or after a single intravenous treatment. This suggests that in vitro assays of oncolytic activity may not predict in vivo efficacy (at least in mouse xenograft models). Whether these findings are relevant for humans remains to be determined.

Measles virus, vaccinia virus, reovirus, and coxsackievirus A21 have been shown to be potent oncolytic agents against MM, and some are already being tested in humans (Peng et al., 2003; Ong et al., 2006; Haralambieva et al., 2007; Thirukkumaran et al., 2003; Lichty et al., 2004; Au et al., 2007). Although these viruses are all potent, they have a fairly limited set of natural serotypes. In contrast, there are more than 51 serotypes of adenovirus. Natural infection, active vaccination, or prior oncolytic therapy will induce humoral and cellular immunity against any of these viruses. Therefore, it may be difficult to apply the same serotype of oncolytic virus in cancer patients who are already immune to this viral serotype. Oncolytic adenoviruses or other viruses with many serotypes may have an advantage in being able to pick and choose serotypes in a patient-specific fashion or for serotype switching, as each treatment generates immunity to itself. Whether adenovirus or these other oncolytics are the “best” agent for MM remains to be determined. A more likely scenario will be that all of these may be used for MM treatment, perhaps even used as combination virotherapies to leverage each other's potencies for better efficacy.

In summary, this work has demonstrated that Ad5, Ad6, Ad26, and Ad48 appear relatively potent at killing MM cells with relative sparing of normal marrow cells. Whether the cell binding of Ad5, Ad6, Ad26, and Ad48 can be increased or targeted to improve oncolysis remains to be determined. Because Ad6, Ad26, and Ad48 have substantially lower seroprevalence than Ad5, these data suggest that they may have utility as therapies in Ad5-immune patients for MM and perhaps other hematologic malignancies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank W.S.M. Wold for providing KB cells and pBHGKD3E3 plasmid and Mary Barry for excellent technical assistance. This project was supported by the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center and the Fraternal Order of Eagles Cancer Research Fund.

Author Disclosure Statement

None of the authors has competing financial interests.

References

- Abbink P. Lemckert A.A. Ewald B.A. Lynch D.M. Denholtz M. Smits S. Holterman L. Damen I. Vogels R. Thorner A.R. O'Brien K.L. Carville A. Mansfield K.G. Goudsmit J. Havenga M.J. Barouch D.H. Comparative seroprevalence and immunogenicity of six rare serotype recombinant adenovirus vaccine vectors from subgroups B and D. J. Virol. 2007;81:4654–4663. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02696-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendt B.K. Ramirez-Alvarado M. Sikkink L.A. Keats J.J. Ahmann G.J. Dispenzieri A. Fonseca R. Ketterling R.P. Knudson R.A. Mulvihill E.M. Tschumper R.C. Wu X. Zeldenrust S.R. Jelinek D.F. Biologic and genetic characterization of the novel amyloidogenic lambda light chain-secreting human cell lines, ALMC-1 and ALMC-2. Blood. 2008;112:1931–1941. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au G.G. Lincz L.F. Enno A. Shafren D.R. Oncolytic coxsackievirus A21 as a novel therapy for multiple myeloma. Br. J. Haematol. 2007;137:133–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry M.A. Behnke C.A. Eastman A. Activation of programmed cell death (apoptosis) by cisplatin, other anticancer drugs, toxins and hyperthermia. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1990;40:2353–2362. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90733-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergelson J.M. Cunningham J.A. Droguett G. Kurt-Jones E.A. Krithivas A. Hong J.S. Horwitz M.S. Crowell R.L. Finberg R.W. Isolation of a common receptor for coxsackie B viruses and adenoviruses 2 and 5. Science. 1997;275:1320–1323. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister W.P. Guilligay D. Cusack S. Wadell G. Arnberg N. Crystal structure of species D adenovirus fiber knobs and their sialic acid binding sites. J. Virol. 2004;78:7727–7736. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.14.7727-7736.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo R. Miest T. Shashkova E.V. Barry M.A. Reprogrammed viruses as cancer therapeutics: Targeted, armed and shielded. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;6:529–540. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doronin K. Toth K. Kuppuswamy M. Ward P. Tollefson A.E. Wold W.S. Tumor-specific, replication-competent adenovirus vectors overexpressing the adenovirus death protein. J. Virol. 2000;74:6147–6155. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.13.6147-6155.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haralambieva I. Iankov I. Hasegawa K. Harvey M. Russell S.J. Peng K.W. Engineering oncolytic measles virus to circumvent the intracellular innate immune response. Mol. Ther. 2007;15:588–597. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofherr S.E. Shashkova E.V. Weaver E.A. Khare R. Barry M.A. Modification of adenoviral vectors with polyethylene glycol modulates in vivo tissue tropism and gene expression. Mol. Ther. 2008;16:1276–1282. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubczak J.L. Rollence M.L. Stewart D.A. Jafari J.D. Von Seggern D.J. Nemerow G.R. Stevenson S.C. Hallenbeck P.L. Adenovirus type 5 viral particles pseudotyped with mutagenized fiber proteins show diminished infectivity of coxsackie B–adenovirus receptor-bearing cells. J. Virol. 2001;75:2972–2981. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.6.2972-2981.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelinek D.F. Ahmann G.J. Greipp P.R. Jalal S.M. Westendorf J.J. Katzmann J.A. Kyle R.A. Lust J.A. Coexistence of aneuploid subclones within a myeloma cell line that exhibits clonal immunoglobulin gene rearrangement: Clinical implications. Cancer Res. 1993;53:5320–5327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyle R.A. Rajkumar S.V. Multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;111:2962–2972. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-078022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavery D.J. Chen-Kiang S. Adenovirus E1A and E1B genes are regulated posttranscriptionally in human lymphoid cells. J. Virol. 1990;64:5349–5359. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.11.5349-5359.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavery D. Fu S.M. Lufkin T. Chen-Kiang S. Productive infection of cultured human lymphoid cells by adenovirus. J. Virol. 1987;61:1466–1472. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.5.1466-1472.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichty B.D. Stojdl D.F. Taylor R.A. Miller L. Frenkel I. Atkins H. Bell J.C. Vesicular stomatitis virus: A potential therapeutic virus for the treatment of hematologic malignancy. Hum. Gene Ther. 2004;15:821–831. doi: 10.1089/hum.2004.15.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T.C. Galanis E. Kirn D. Clinical trial results with oncolytic virotherapy: A century of promise, a decade of progress. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2007;4:101–117. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin K. Brie A. Saulnier P. Perricaudet M. Yeh P. Vigne E. Simultaneous CAR- and αV integrin-binding ablation fails to reduce Ad5 liver tropism. Mol. Ther. 2003;8:485–494. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeker T.C. Lay L.T. Wroblewski J.M. Turturro F. Li Z. Seth P. Adenoviral vectors efficiently target cell lines derived from selected lymphocytic malignancies, including anaplastic large cell lymphoma and Hodgkin's disease. Clin. Cancer Res. 1997;3:357–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong H.T. Timm M.M. Greipp P.R. Witzig T.E. Dispenzieri A. Russell S.J. Peng K.W. Oncolytic measles virus targets high CD46 expression on multiple myeloma cells. Exp. Hematol. 2006;34:713–720. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng K.W. Donovan K.A. Schneider U. Cattaneo R. Lust J.A. Russell S.J. Oncolytic measles viruses displaying a single-chain antibody against CD38, a myeloma cell marker. Blood. 2003;101:2557–2562. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson B.D. Reiter D.M. Marttila M. Mei Y.F. Casasnovas J.M. Arnberg N. Stehle T. Adenovirus type 11 binding alters the conformation of its receptor CD46. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:164–166. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson B.D. Müller S. Reiter D.M. Schmitt B.B. Marttila M. Sumowski C.V. Schweizer S. Scheu U. Ochsenfeld C. Arnberg N. Stehle T. An arginine switch in the species B adenovirus knob determines high-affinity engagement of cellular receptor CD46. J. Virol. 2009;83:673–686. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01967-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piedra P.A. Poveda G.A. Ramsey B. McCoy K. Hiatt P.W. Incidence and prevalence of neutralizing antibodies to the common adenoviruses in children with cystic fibrosis: Implication for gene therapy with adenovirus vectors. Pediatrics. 1998;101:1013–1019. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.6.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelvink P.W. Mi Lee G. Einfeld D.A. Kovesdi I. Wickham T.J. Identification of a conserved receptor-binding site on the fiber proteins of CAR-recognizing Adenoviridae. Science. 1999;286:1568–1571. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5444.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiradake E. Henaff D. Wodrich H. Billet O. Perreau M. Hippert C. Mennechet F. Schoehn G. Lortat-Jacob H. Dreja H. Ibanes S. Kalatzis V. Wang J.P. Finberg R.W. Cusack S. Kremer E.J. The cell adhesion molecule “CAR” and sialic acid on human erythrocytes influence adenovirus in vivo biodistribution. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000277. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shashkova E.V. Doronin K. Senac J.S. Barry M.A. Macrophage depletion combined with anticoagulant therapy increases therapeutic window of systemic treatment with oncolytic adenovirus. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5896–5904. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shashkova E.V. May S. Barry M.A. Characterization of human adenovirus serotypes 5, 6, 11, and 35 as anticancer agents. Virology. 2009;394:311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shayakhmetov D.M. Li Z.Y. Ternovoi V. Gaggar A. Gharwan H. Lieber A. The interaction between the fiber knob domain and the cellular attachment receptor determines the intracellular trafficking route of adenoviruses. J. Virol. 2003;77:3712–3723. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.6.3712-3723.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teoh G. Chen L. Urashima M. Tai Y.T. Celi L.A. Chen D. Chauhan D. Ogata A. Finberg R.W. Webb I.J. Kufe D.W. Anderson K.C. Adenovirus vector-based purging of multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 1998;92:4591–4601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thirukkumaran C.M. Luider J.M. Stewart D.A. Cheng T. Lupichuk S.M. Nodwell M.J. Russell J.A. Auer I.A. Morris D.G. Reovirus oncolysis as a novel purging strategy for autologous stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2003;102:377–387. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorner A.R. Vogels R. Kaspers J. Weverling G.J. Holterman L. Lemckert A.A. Dilraj A. McNally L.M. Jeena P.M. Jepsen S. Abbink P. Nanda A. Swanson P.E. Bates A.T. O'Brien K.L. Havenga M.J. Goudsmit J. Barouch D.H. Age dependence of adenovirus-specific neutralizing antibody titers in individuals from sub-Saharan Africa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44:3781–3783. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01249-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Raaij M.J. Mitraki A. Lavigne G. Cusack S. A triple β-spiral in the adenovirus fibre shaft reveals a new structural motif for a fibrous protein. Nature. 1999;401:935–938. doi: 10.1038/44880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. Liaw Y.C. Stone D. Kalyuzhniy O. Amiraslanov I. Tuve S. Verlinde C.L. Shayakhmetov D. Stehle T. Roffler S. Lieber A. Identification of CD46 binding sites within the adenovirus serotype 35 fiber knob. J. Virol. 2007;81:12785–12792. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01732-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wattel E. Vanrumbeke M. Abina M.A. Cambier N. Preudhomme C. Haddada H. Fenaux P. Differential efficacy of adenoviral mediated gene transfer into cells from hematological cell lines and fresh hematological malignancies. Leukemia. 1996;10:171–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham T.J. Mathias P. Cheresh D.A. Nemerow G.R. Integrins αvβ3 or αvβ5 promote adenovirus internalization but not virus attachment. Cell. 1993;73:309–319. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90231-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]