Abstract

AIMS

To investigate the effects of age and chronic heart failure (CHF) on the oral disposition kinetics of fluvoxamine.

METHODS

A single fluvoxamine dose (50 mg) was administered orally to 10 healthy young adults, 10 healthy elderly subjects and 10 elderly patients with CHF. Fluvoxamine concentration in plasma was measured for up to 96 h.

RESULTS

With the exception of apparent distribution volume, ageing modified all main pharmacokinetic parameters of fluvoxamine. Thus, peak concentration was about doubled {31 ± 19 vs. 15 ± 9 ng ml−1; difference [95% confidence interval (CI)] 16 (3, 29), P < 0.05}, and area under the concentration–time curve was almost three times higher [885 ± 560 vs. 304 ± 84 ng h ml−1; difference (95% CI) 581 (205, 957), P < 0.05]; half-life was prolonged by 63% [21.1 ± 6.2 vs. 12.9 ± 6.4 h; difference (95% CI) 8.2 (2.3, 14.1), P < 0.01], and oral clearance was halved (1.12 ± 0.77 vs. 2.25 ± 0.66 l h−1 kg−1; difference (95% CI) −1.13 (−1.80, −0.46), P < 0.001]. A significant inverse correlation was consistently observed between age and oral clearance (r=−0.67; P < 0.001). The coexistence of CHF had no significant effect on any pharmacokinetic parameters in elderly subjects.

CONCLUSIONS

Ageing results in considerable impairment of fluvoxamine disposition, whereas CHF causes no significant modifications. Therefore, adjustment of initial dose and subsequent dose titrations may be required in elderly subjects, whereas no further dose reduction is necessary in elderly patients with CHF.

Keywords: age, fluvoxamine, heart failure, pharmacokinetics

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ABOUT THIS SUBJECT

The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluvoxamine is a first-choice antidepressant agent for treatment of depression and anxiety disorders in elderly subjects and patients with cardiovascular diseases.

Limited and conflicting data are available regarding age-related modifications of fluvoxamine pharmacokinetics.

No study has yet investigated the possible alterations of fluvoxamine pharmacokinetics in elderly patients with chronic heart failure (CHF).

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

The oral disposition kinetics of fluvoxamine is significantly impaired in elderly subjects, mean oral clearance being halved with respect to young adults.

In elderly patients with CHF, fluvoxamine pharmacokinetics is not altered with respect to age-matched healthy subjects.

Introduction

Fluvoxamine is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) that is widely prescribed for the treatment of depression [1] and various anxiety disorders [2]. Pharmacokinetic studies have shown that fluvoxamine is almost completely absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, since 94% of an oral dose is recovered in urine (virtually entirely in the form of metabolites [3]). However, the only study in which the drug was administered intravenously reported a mean absolute bioavailability of only 53% [4], indicating that it is subjected to considerable presystemic metabolism. Fluvoxamine is extensively metabolized in the liver to at least 11 biotransformation products, nine of which have been identified and shown to be devoid of any significant pharmacological activity [3, 5]. Fluvoxamine metabolism has not been studied in vitro; on the basis of indirect evidence from clinical studies, cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A1 and 2D6 have been proposed to be implicated in its biotransformation, but controversial results have been obtained concerning the involvement of either enzyme. In vivo correlation studies with validated markers of CYP1A2 activity found a weak relationship between fluvoxamine oral clearance and caffeine N-3-demethylation [6], or no correlation with caffeine clearance or the paraxanthine/caffeine ratio [7]. Evidence for partial involvement of CYP1A2 in fluvoxamine metabolism was obtained from a comparison of fluvoxamine pharmacokinetics between nonsmokers and smokers, in whom CYP1A2 is known to be induced [8]. Area under the concentration–time curve and peak concentration were about 30% lower in smokers, but fluvoxamine oral clearance, although increased by about 20%, was nonsignificantly different from that of nonsmoking subjects. Consistent with these results, steady-state fluvoxamine concentration [9] and steady-state concentration-to-dose ratio [10] were shown to be nonsignificantly reduced in smokers with respect to nonsmokers. As regards the polymorphic enzyme CYP2D6, a significant contribution of this CYP isoform has been proposed on the basis of co-segregation of fluvoxamine with debrisoquine metabolism [6], whereas indications of a minor to moderate role of CYP2D6 have been obtained when dextromethorphan was used as phenotyping agent [11].Consistent with the latter finding, a plot of dose-normalized AUC after administration of 50 or 100 mg to 98 individuals did not reveal any bimodal distribution, as would be expected if CYP2D6 were the rate-limiting enzyme in fluvoxamine metabolic disposition [12]. In addition, a barely significant impact of the CYP2D6 genotype has recently been observed on fluvoxamine steady-state concentration at a low (50 mg) daily dose, and no genotype effect at higher dosages [13].

Depression is the most common mental health problem in the elderly. Like other SSRIs, fluvoxamine is as efficacious as tricyclic antidepressants in geriatric depression, but is much better tolerated because it is virtually devoid of the anticholinergic and anti-adrenergic activities typical of tricyclics [14, 15]. Although fluvoxamine is widely prescribed in this patient population, its pharmacokinetics in elderly subjects has not been adequately studied. Most of available information derives from data on file of manufacturers or studies published as abstracts, generally reporting no major effect of age on fluvoxamine pharmacokinetics (reviewed in refs. [1–3]). Two review articles stating that fluvoxamine clearance is reduced by about 50% in the elderly provide no reference supporting their statement [15, 16]. The only formal pharmacokinetic study addressing this question [12] obtained somewhat inconsistent results, since mean terminal half-life was found 16% longer in elderly individuals, whereas mean AUC was 32% lower than in young subjects, suggesting an age-related increase in oral clearance (which was not reported in that study). Although neither difference was statistically significant, this may have been due, as noted by the authors, to the inadequate size of the control group (six young individuals).

Late-life depression often coexists with chronic illnesses, notably cardiovascular diseases, a comorbidity which is considered an inevitable consequence of the relationship between the two conditions [17, 18]. SSRIs are the first-line antidepressant treatment in patients with cardiac diseases [17]; however, the various studies performed in this patient population mainly focused on the safety characteristics of fluvoxamine [15, 19], and the possible pharmacokinetic modifications associated with cardiac failure remain to be investigated. Accordingly, the present study had the following objectives:

To reassess the effect of age on the oral disposition kinetics of fluvoxamine.

To investigate whether the pharmacokinetics of fluvoxamine is altered in patients with cardiac failure.

To this end, the oral disposition kinetics of fluvoxamine was studied in healthy young adults, healthy elderly subjects, and elderly patients with chronic heart failure (CHF).

Methods

Subjects

Thirty White male subjects participated in the study, after informed written consent had been obtained. Ten were healthy young adults and 10 healthy elderly subjects (age ≥65 years), who were recruited from outpatients attending the hospital for routine laboratory tests; 10 were elderly patients with CHF. Young and elderly volunteers were diagnosed as healthy on the basis of a thorough clinical examination, including medical history, physical examination, electrocardiogram, echocardiography, and standard laboratory tests. Patients were eligible for the study if they had a diagnosis of heart failure for at least 3 months before the study, had an ejection fraction of ≤40% and were not taking drugs known to interfere with fluvoxamine pharmacokinetics (see below). All patients had stable New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III (n= 6) or IV (n= 4) symptoms. Underlying pathologies were hypertension and ischaemic heart disease in seven and three patients, respectively. Inclusion criteria for selection of both healthy subjects and patients were that they were nonsmokers, were not heavy consumers of alcohol and had normal liver function (see Results). All participants were requested to abstain from alcohol, grapefruit juice and caffeine-containing beverages during the preceding week and throughout the study period.

Study design

The study design was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Padova (Padova, Italy). On study day 1, after an overnight fast, at 08.00 h, all participants received one 50-mg tablet of fluvoxamine (Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Weesp, the Netherlands). They were asked to report any subjective adverse effects and their vital signs were closely monitored. A single-dose protocol had to be adopted for this study, because multiple dosing was not considered ethical for our CHF patients, who were not receiving fluvoxamine for therapeutic purposes. After dosing, all subjects remained sitting for 2 h; a light meal was provided after 4 h. Blood samples were collected in heparinized plastic tubes at 0 (predose), 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 24, 30, 36, 48, 60, 72 and 96 h after dosing. Blood was centrifuged immediately after collection and stored at −40°C until assayed.

Materials and analytic methods

Fluvoxamine and clovoxamine (internal standard) were kindly supplied by Solvay Pharmaceuticals. Triethylamine was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). All organic solvents and other chemicals were of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade.

Plasma concentrations of fluvoxamine were determined by HPLC, with ultraviolet detection, using the method of Madsen et al. [20], with minor modifications. Briefly, 1 ml of plasma was added to 20 µl of internal standard (a methanolic solution of 10 ng ml−1 clovoxamine), 100 µl of 1 M sodium hydroxide and 5 ml of heptane/isoamyl alcohol 98.5 : 1.5 (v/v). The mixture was shaken for 15 min and then centrifuged for 10 min at 5000 g. The organic phase was then transferred into a test tube containing 100 µl of 0.1 M hydrochloric acid. This mixture was shaken for 15 min and then centrifuged for 10 min at 5000 g. Fifty microlitres of the acidic layer were injected into a reversed phase C18 Sunfire column (150 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm; Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The mobile phase consisted of 30% acetonitrile and 70% of 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 3.5) containing 0.12% of triethylamine (v/v). The flow rate was 1 ml min−1, and ultraviolet detection was performed at 254 nm. The limit of quantification for fluvoxamine was 1 ng ml−1. Intra- and interassay coefficients of variations (n= 10) for fluvoxamine were <4% at 2 ng ml−1 and <2% at 40 ng ml−1.

Pharmacokinetic and statistical analyses

Because of the irregular shapes of the concentration–time curves (see Results), data could not be fitted to any polyexponential equation, and model-independent pharmacokinetic parameters were evaluated. The peak plasma fluvoxamine concentration (Cmax) and the time of its occurrence (tmax) were the observed values. Terminal half-life (t1/2) was obtained by log-linear regression analysis of the terminal phase of the concentration–time curves. The area under the plasma drug concentration–time curve (AUC) was calculated by the linear trapezoidal rule up to the last determined concentration and was extrapolated to infinity by adding the quotient of the last measured concentration to the elimination rate constant (λz). The extrapolated portion was always <10% of the total area. Oral clearance (CL/F, where F is bioavailability) was calculated as dose/AUC, and the apparent distribution volume of the terminal phase (Vz/F) as dose/(λz AUC).

A two-tail power analysis [CSS power assessment procedure (CSS, Statsoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA)] based on the mean difference in oral clearance between young and elderly subjects showed that, with 10 subjects per group and a significance level (α) of 0.05, power (1–β) was 0.93. Pharmacokinetic parameters were tested for normal distribution by use of the Shapiro–Wilk test [SAS univariate procedure (SAS software, release 9.1.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA)] and for homogeneity of variances by use of the Levene test (CSS Levene test of homogeneity of variances). Since normal distribution of the data could not be rejected, comparisons were made by one-way anova, via a general linear model (SAS GLM procedure). In the case of significant differences (α= 0.05) the anova was followed by the Newman–Keuls multiple comparisons test for pair-wise comparisons. For tmax, the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test was used. Unless otherwise specified, data are presented as mean ± SD. Differences between means with 95% confidence intervals are also given. Nonparametric confidence intervals for tmax were calculated according to Decker [21] by means of SAS software. Correlations were examined by linear regression analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The characteristics of the subjects studied are listed in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between the three study groups in weight, height or body mass index; neither was mean age significantly different between healthy elderly subjects and patients with CHF. The ejection fraction values of healthy elderly subjects were in the normal range [22] and very similar to those of young adults. On the basis of the serum levels of conventional markers of liver and kidney functions, no significant differences were observed between the three study groups. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR), estimated by means of the formula of Cockcroft and Gault [23], is indicative of normal age-related kidney function in healthy elderly subjects [24]. The mild decrease in GFR in CHF patients can be explained by their cardiac disease [25]. Linear correlation analysis either within single study groups or including all participants showed no relationship between fluvoxamine oral clearance and estimated GFR (results not shown). Co-administered drugs are listed in Table 2. None of these drugs has been reported to interfere with fluvoxamine pharmacokinetics [26].

Table 1.

Summary of demographic and clinical characteristics

| Subject characteristic (normal range) | Young subjects (n= 10) | Elderly subjects (n= 10) | CHF patients (n= 10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 35 ± 7 | 73 ± 7* | 79 ± 6* |

| Weight (kg) | 79 ± 10 | 78 ± 9 | 75 ± 11 |

| Height (cm) | 176 ± 11 | 170 ± 7 | 166 ± 10 |

| Body mass index (kg m−2) | 26 ± 4 | 27 ± 2 | 27 ± 4 |

| Ejection fraction (67 ± 8%) | 64 ± 6 | 63 ± 7 | 31 ± 4** |

| Albumin (35–55 g l−1) | 43 ± 4 | 40 ± 4 | 39 ± 4 |

| Bilirubin (5–17 µmol l−1) | 10.4 ± 4.2 | 13.6 ± 7.1 | 14.9 ± 4.8 |

| AST (10–45 U l−1) | 27 ± 10 | 20 ± 5 | 29 ± 9 |

| ALT (10–50 U l−1) | 29 ± 11 | 22 ± 10 | 27 ± 14 |

| γ-GT (3–65 U l−1) | 27 ± 16 | 35 ± 22 | 24 ± 12 |

| P-Urea (2.50–7.50 mmol l−1) | 5.2 ± 1.4 | 6.3 ± 2.2 | 6.9 ± 1.6 |

| P-creatinine (62–115 µmol l−1) | 87 ± 14 | 84 ± 21 | 99 ± 11 |

| Estimated GFR (ml min−1)† | 120 ± 32 | 81 ± 20* | 62 ± 15*** |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD.

P < 0.05 vs. young subjects;

P < 0.01 vs. young and elderly subjects;

P < 0.001 vs. young subjects, NS vs. elderly subjects.

Calculated according to Cockcroft and Gault [23]. CHF, chronic heart failure; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; γ-GT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; GFR, glomerular filtration rate.

Table 2.

Medications taken by study subjects in different groups

| Study group | Drugs* |

|---|---|

| Young subjects | None |

| Elderly subjects | Lorazepam (n= 3); dutasteride |

| CHF patients | Furosemide (n= 10); aspirin (n= 7); lansoprazole (n= 6); digoxin (n= 4); ramipril (n= 4); enalapril (n= 3); warfarin (n= 3) clopidogrel (n= 3); amlodipine (n= 3); simvastatin (n= 3); carvedilol (n= 3); metoprolol (n= 3); isosorbide (n= 3); diltiazem (n= 2); irbesartan (n= 2); allopurinol (n= 2); moxifloxacin (n= 2); spironolactone (n= 2); prednisone; thiamazole; amoxicillin + clavulanic acid; tamsulosin; nadroparin |

The number of study subjects taking each medication is given in parentheses (no number indicates that only one subject received the drug).

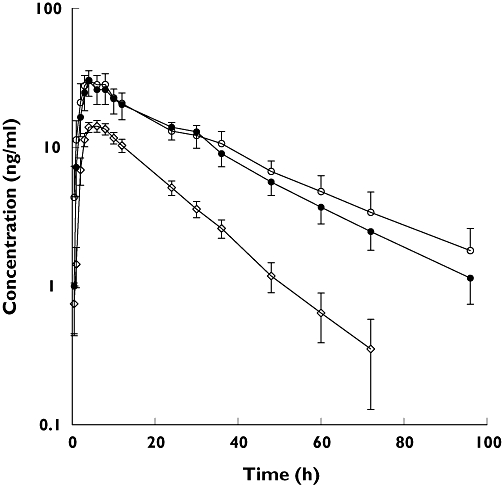

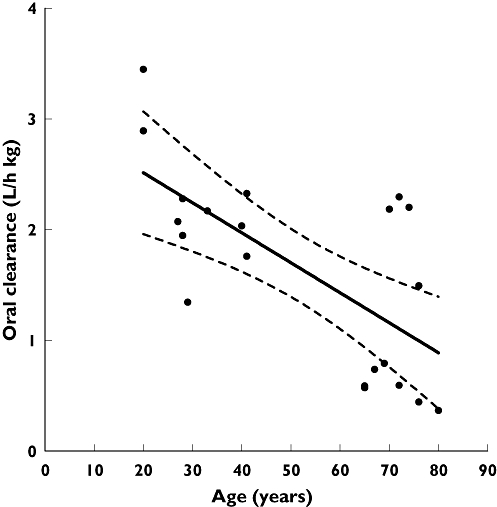

The time courses of fluvoxamine concentration in the three study groups are shown in Figure 1. It is evident that in each group the semilogarithmic plot of concentration–time data exhibits a convex concentration–time profile during the decay phase. In accordance with previous observations [6, 11, 12], a small secondary peak and/or a ‘shoulder’ was apparent in almost all individual curves, so that a linear decay could not be observed until 24–48 h after fluvoxamine administration. A visual comparison of the three concentration–time curves reveals that fluvoxamine mean plasma levels were considerably higher in elderly than young subjects, and the elimination rate was significantly reduced. By contrast, the concentration–time profile of elderly patients with CHF was almost superimposable on that of healthy elderly individuals. Table 3 consistently shows that, with the exception of tmax and Vz/F, the values of pharmacokinetic parameters in elderly subjects were significantly different from those measured in young adults. Thus, Cmax was about doubled, AUC was almost three times higher, CL/F was approximately halved and t1/2 was prolonged by 63%. The relationship between oral clearance and age is shown in Figure 2. A highly significant inverse correlation was observed between age and oral clearance (r=−0.67; P < 0.001). Small, statistically nonsignificant differences in pharmacokinetic parameters were observed between healthy elderly subjects and elderly patients with CHF.

Figure 1.

Mean plasma concentration vs. time profiles of fluvoxamine after oral administration of a single 50-mg dose to young subjects (diamonds), elderly subjects (solid circles), and chronic heart failure (CHF) patients (open circles). Bars represent SEM. Concentrations below the limit of quantification were considered zero for calculation of mean concentrations

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of fluvoxamine

| Pharmacokinetic parameter | Young subjects (n= 10) | Elderly subjects (n= 10) | CHF patients (n= 10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (ng h ml−1) | 304 ± 84 | 885 ± 560* | 988 ± 602† |

| Difference (95% CI) | 581 (205, 957)‡ | 103 (−443, 649)§ | |

| CL/F (l h−1 kg−1) | 2.25 ± 0.66 | 1.12 ± 0.77*** | 0.88 ± 0.41† |

| Difference (95% CI) | −1.13 (−1.80, −0.46)‡ | −0.24 (−0.82, 0.34)§ | |

| Vz/F (l kg−1) | 35 ± 10 | 33 ± 20 | 31 ± 17† |

| Difference (95% CI) | −2 (−17, 13)‡ | −2 (−19, 15)§ | |

| t1/2 (h) | 12.9 ± 6.4 | 21.1 ± 6.2** | 25.2 ± 7.5† |

| Difference (95% CI) | 8.2 (2.3, 14.1)‡ | 4.1 (−2.4, 10.6)§ | |

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 15 ± 3 | 31 ± 19* | 36 ± 20† |

| Difference (95% CI) | 16 (3, 29)‡ | 5 (−13, 23)§ | |

| tmax (h) | 5 (4–8)¶ | 4 (2–8)¶ | 4 (2–8)†¶ |

| Difference (95% CI) | −1 (−2, 0)‡ | 0 (−2, 0)§ |

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001 vs. young subjects.

Non-significant (P > 0.05) vs. healthy elderly subjects.

With respect to young subjects.

With respect to elderly subjects.

Median value (range). Data are expressed as mean ± SD; differences between means or medians (for tmax) are also given with respective 95% CI.

Figure 2.

Relationship between fluvoxamine oral clearance and age in 20 healthy subjects. Dotted lines show the 95% confidence interval for the regression line

Fluvoxamine, in a single 50-mg dose, was well tolerated, except in two elderly subjects and three patients with CHF, who had transient nausea and/or drowsiness. No significant changes in vital signs were recorded during the course of the study.

Discussion

An inconsistent picture has so far emerged from studies investigating the effect of age on fluvoxamine pharmacokinetics. Thus, authors reviewing those studies either concluded that there is no need for dosage modification in depressed elderly patients [3, 27–29] or recommended that the initial dose and subsequent dose titrations be modified in this patient group [2, 5]. The only formal pharmacokinetic study that has so far investigated the oral disposition kinetics of fluvoxamine in elderly subjects found no age-related alterations of fluvoxamine pharmacokinetic parameters [12]. However, it included a control group of only six young subjects. The present study, which compared young and elderly groups of adequate size (statistical power = 93%), clearly shows that oral fluvoxamine disposition is significantly impaired in old age, since oral clearance is halved in elderly subjects. It should be noted that mean fluvoxamine plasma levels observed by us in young adults (AUC = 304 ng h ml−1, Cmax= 15 ng ml−1) are comparable to those obtained by previous studies in which the same single dose (50 mg) was administered to subjects of similar age (AUC = 232–353 ng h ml−1; Cmax= 14–18 ng ml−1[7, 8, 11]). Thus, the lack of pharmacokinetic differences between young and elderly subjects in the study of De Vries et al. [12] may be due to the coincidentally high values observed in the small young group (AUC = 652 ng h ml−1; Cmax= 30 ng ml−1, after a single 50-mg dose).

Very different mean values for terminal half-life (ranging from 9.6 h [7] to 19 h [12]) have previously been reported for young adults. All previous t1/2 values have been obtained from concentration–time curves up to 48 h, or including one additional data point at 72 h. We observed that, in many cases, the decay curves do not become log-linear until 48 h (see Figure 1), thereby precluding reliable determination of t1/2 unless the sampling protocol includes at least two more data points. Our t1/2 values are very similar to those obtained by Van Harten et al. [4], after intravenous administration of 10 and 30 mg of fluvoxamine (12 and 13 h, respectively).

In principle, the decrease in oral clearance (CL/F) here observed in elderly subjects may be due to a reduction in systemic clearance (CL), an increase in bioavailability (F), or both. Our observation that Cmax and t1/2 are both significantly increased in elderly individuals is suggestive of an age-related decrease in both systemic and presystemic clearances of fluvoxamine. Since, unlike the activity of various other hepatic CYPs, that of CYP2D6 is not appreciably reduced in older age [30], the marked pharmacokinetic changes observed in elderly subjects do not appear consistent with any major role of this CYP isoform in fluvoxamine metabolism.

Conditions such as CHF, in which cardiac output is decreased, are associated with a reduced hepatic blood flow and, according to pharmacokinetic theory, are expected to cause a reduction in hepatic clearance of drugs with high extraction ratio (>0.7), since their clearance is limited by blood flow [31]. However, large decreases in clearance in patients with CHF have also been reported for drugs such as theophylline [32], with a very low extraction ratio (about 0.10 [33]), indicating that the intrinsic metabolic activity of the liver may also be decreased in cardiac failure. Factors possibly responsible for this include hypoxia and increased cytokine levels [34]. The effect of hypoxia on CYP activity is well established [35]. It is now recognized that CHF is a state of chronic inflammation with elevated circulating levels of proinflammatory cytokines [36], an increase that is positively correlated with the NYHA class [37]. These inflammatory mediators have been shown to cause downregulation of various CYP isoforms and other drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters, although there are also reports that some drug-metabolizing CYPs are unaffected or even induced by inflammation [38]. Based on these observations, we considered the possibility that CHF may also modify the disposition of fluvoxamine, although available data (virtually complete absorption, mean absolute bioavailability = 0.53; see above) indicate that it is a drug with a moderate extraction ratio (0.47, since extraction ratio = 1 −F for a completely absorbed drug [31]). As a matter of fact, our results indicate that CHF causes no additional modification of the absorption or disposition kinetics of fluvoxamine beyond that observed in the healthy elderly. The small, statistically nonsignificant decrease in oral clearance observed in CHF patients may be explained by the small difference in age with respect to healthy elderly volunteers. As shown in the Results section, a significant inverse correlation exists between age and oral clearance of healthy subjects. Inclusion of CHF patients in this correlation analysis yields a regression line with a slope virtually identical to that obtained in the absence of this patient group (−0.0273 vs.−0.0271) and a correlation of still greater strength and significance (r=−0.73; P < 0.0001). Thus, the small decrease in oral clearance observed in CHF patients is not greater than can be explained by their slightly older age. The uncertainty regarding the CYP isoforms responsible for fluvoxamine metabolism and the still incomplete knowledge of the effect of CHF on human CYP expression preclude any unambiguous interpretation of our observations in cardiac patients.

In conclusion, our results show that the mean oral clearance of fluvoxamine is approximately halved in elderly subjects with respect to young individuals, whereas no further reduction is observed in elderly patients with CHF. Therefore, the average steady-state concentration upon multiple dosing, which is inversely proportional to the CL/F value [31], is expected to be twice as high in aged patients, at least at low daily dosages. Twice as high steady-state concentrations in elderly patients have been observed with other SSRIs such as citalopram, paroxetine and fluoxetine/norfluoxetine [14]. Although a relationship between steady-state concentration and clinical effects or a ‘therapeutic window’ has not been established for fluvoxamine, treatment-limiting adverse events and inhibitory effects on CYP enzymes have been shown to correlate with serum concentrations [39, 40]. The latter effects, which involve three CYP isoforms (1A2, 2C19 and 3A4 in order of decreasing sensitivity to inhibition [28, 29]), are of major concern when prescribing fluvoxamine to elderly patients, as these patients are often given multiple medications and are generally more sensitive to any adverse effects arising from elevated concentrations of co-administered drugs. On the basis of the extent and statistical significance of the clearance reduction here observed, fluvoxamine dose should be approximately halved in elderly patients. However, it can be noted from both Table 3 and Figure 2 that, as generally observed in elderly people [30], interindividual variability in fluvoxamine oral clearance is larger in older subjects, so that there is some overlap with the clearance values of younger individuals. This implies that mean data can be considered only an approximate guide to dose adjustment and that elderly patients should be approached individually; it appears advisable to start fluvoxamine therapy with half the recommended dose and closely monitor patients for side-effects and medication interactions in the event that inadequate clinical response requires upward dose adjustments.

Competing interests

None to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilde MI, Plosker GL, Benfield P. Fluvoxamine. An updated review of its pharmacology, and therapeutic use in depressive illness. Drugs. 1993;46:895–924. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199346050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Figgitt DP, McClellan KJ. Fluvoxamine. An updated review of its use in the management of adults with anxiety disorders. Drugs. 2000;60:925–54. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200060040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perrucca E, Gatti G, Spina E. Clinical pharmacokinetics of fluvoxamine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1994;27:175–90. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199427030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Harten J, Lönneba A, Grahnén A. Pharmacokinetics of fluvoxamine after intravenous and oral administration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1994;10(Suppl.):104. [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeVane CL, Gill HS. Clinical pharmacokinetics of fluvoxamine: applications to dosage regimen design. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(Suppl. 5):7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrillo JA, Dahal ML, Svensson JO, Alm C, Rodríguez I, Bertilsson L. Disposition of fluvoxamine in humans is determined by the polymorphic CYP2D6 and also by the CYP1A2 activity. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;60:183–90. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spigset O, Hägg S, Söderström E, Dahlqvist R. Lack of correlation between fluvoxamine clearance and CYP1A2 activity as measured by systemic caffeine clearance. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;54:943–6. doi: 10.1007/s002280050579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spigset O, Carleborg L, Hedenmalm K, Dahlqvist R. Effect of cigarette smoking on fluvoxamine pharmacokinetics in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1995;58:399–403. doi: 10.1016/0009-9236(95)90052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerstenberg G, Aoshima T, Fukasawa T, Yoshida K, Takahashi H, Higuchi H, Murata Y, Shimoyama R, Ohkubo T, Shimizu T, Otani K. Effect of the CYP2D6 genotype and cigarette smoking on the steady-state plasma concentrations of fluvoxamine and its major metabolite fluvoxamine acid in Japanese depressed patients. Ther Drug Monit. 2003;25:463–8. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200308000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugahara H, Maebara C, Ohtani H, Handa M, Ando K, Mine K, Kubo C, Ieiri I, Sawada Y. Effect of smoking and CYP2D6 polymorphism on the extent of fluvoxamine–alprazolam interaction in patients with psychosomatic disease. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:699–704. doi: 10.1007/s00228-009-0629-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spigset O, Granberg K, Hägg S, Norström Å, Dahlqvist R. Relationship between fluvoxamine pharmacokinetics and CYP2D6/CYP2C19 phenotype polymorphisms. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;52:129–33. doi: 10.1007/s002280050261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Vries MH, Raghoebar M, Mathlener IS, van Harten J. Single and multiple oral dose fluvoxamine kinetics in young and elderly subjects. Ther Drug Monit. 1992;14:493–8. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199212000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe J, Suzuki Y, Fukui N, Sugai T, Ono S, Inoue Y, Someya T. Dose-dependent effect of the CYP2D6 genotype on the steady-state fluvoxamine concentration. Ther Drug Monit. 2008;30:705–8. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e31818d73b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Draper B, Berman K. Tolerability of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Issues relevant to the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:501–19. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newhouse PA. Use of serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors in geriatric depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(Suppl. 5):12–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arky R, editor. Physician's Desk Reference. 51st edn. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics; 1997. Luvox (fluvoxamine) pp. 2723–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whooley MA. Depression and cardiovascular disease. Healing the broken-hearted. JAMA. 2006;295:2874–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.24.2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenzweig-Lipson S, Beyer CE, Hughes ZA, Khawaja X, Rajarao SJ, Malberg JE, Rahman Z, Ring RH, Schechter LE. Differentiating antidepressants of the future: efficacy and safety. Pharmacol Ther. 2007;113:134–53. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hale AS. New antidepressants: use in high-risk patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54(Suppl.):61–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madsen H, Enggaard TP, Hansen LL, Klitgaard NA, Brösen K. Fluvoxamine inhibits the CYP2C9 catalyzed biotransformation of tolbutamide. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;69:41–7. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2001.112689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Decker C. Calculating a nonparametric estimate and confidence interval using SAS® software. Available at http://www.lexjansen.com/pharmasug/2000/Coders/cc01.pdf (last accessed 13 October 2009.

- 22.Braunwald E. Normal and abnormal myocardial function. In: Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo D, Jameson JL, editors. Principles of Internal Medicine. 16th. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005. pp. 1358–67. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16:31–41. doi: 10.1159/000180580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Green T, Levey AS. Assessing kidney function – measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fliser D, Franek E, Joest M, Block S, Mutschler E, Ritz E. Renal function in the elderly: impact of hypertension and cardiac function. Kidney Int. 1997;51:1196–204. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baxter K, editor. Stockley's Drug Interactions. 8th. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2008. SSRIs, tricyclic and related antidepressants; pp. 1203–46. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benfield P, Ward A. Fluvoxamine. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic efficacy in depressive illness. Drugs. 1986;32:313–34. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198632040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Harten J. Clinical pharmacokinetics of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1993;24:203–20. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199324030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baumann P. Care of depression in the elderly: comparative pharmacokinetics of SSRIs. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998;13(Suppl. 5):35–43. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199809005-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lotrich FE, Pollock BG. Aging and clinical pharmacology: implications for antidepressants. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45:1106–22. doi: 10.1177/0091270005280297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rowland M, Tozer TN. Clinical Pharmacokinetics: Concepts and Applications. 3rd. Baltimore, MD: Lea & Febiger; 1995. pp. 156–83. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuntz HD, Straub H, May B. Theophylline elimination in congestive heart failure. Klin Wochenschr. 1983;61:1105–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01496473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orlando R, Padrini R, Perazzi M, De Martin S, Piccoli P, Palatini P. Liver dysfunction markedly decreases the inhibition of cytochrome P450 1A2-mediated theophylline metabolism by fluvoxamine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;79:489–99. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zordoky BNM, El-Kadi AOS. Modulation of cardiac and hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes during heart failure. Curr Drug Metab. 2008;9:122–8. doi: 10.2174/138920008783571792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fradette C, Du Souich P. Effect of hypoxia on cytochrome P450 activity and expression. Curr Drug Metab. 2004;5:257–71. doi: 10.2174/1389200043335577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.El-Menyar AA. Cytokines and myocardial dysfunction: state of the art. J Card Fail. 2008;14:61–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Y, Zhou Y, Meng L, Lu X, Ou N, Li X. Inflammatory mediators in Chinese patients with congestive heart failure. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49:591–9. doi: 10.1177/0091270009333265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morgan ET. Impact of infectious and inflammatory disease on cytochrome P450-mediated drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;85:434–8. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Preskorn SH. Clinically relevant pharmacology of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. An overview with emphasis on pharmacokinetics and effects on oxidative drug metabolism. Clin Parmacokinet. 1997;32(Suppl. 1):1–21. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199700321-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hiemke C, Härtter S. Pharmacokinetics of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Pharmacol Ther. 2000;85:11–28. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(99)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]