Abstract

The concern over increasing rates of obesity and associated health issues have led to calls for solutions to the potentially unhealthy influence of television and food advertising on children's diets. Research demonstrates that children's food preferences are acquired through learning processes, and that these preferences have long-lasting effects on diet. We examined food preferences and eating behaviors among college students, and assessed the relative influence of two potential contributors: parental communication and television experience. In line with previous studies with children, prior television experience continued to predict unhealthy food preferences and diet in early adulthood, and perceived taste had the most direct relationship to both healthy and unhealthy diets. In addition, both television experience and parenting factors independently influenced preferences and diet. These findings provide insights into the potential effectiveness of alternative media interventions to counteract the unhealthy influence of television on diet, including nutrition education, parental communication and media literacy education to teach children to defend against unwanted influence, and reduced exposure to unhealthy messages.

The incidence of obesity in the U.S. has risen dramatically over the past 30 years (Ogden, et al., 2006). The trend is especially disturbing among children. In 2004, over one-third of children and adolescents were overweight or at risk of becoming overweight: more than triple the percentage in 1971. Reduced physical activity and increased consumption of low-nutrient calorie-dense foods are both major contributors, and health authorities believe that the prevalence of advertising for unhealthy food on children's television is a leading cause of children's increasingly unhealthy diet (Brownell & Horgen, 2004; Institute of Medicine (IOM), 2006).

The public discussion about possible solutions to the obesity crisis among children, however, can digress into an argument over who is most to blame for overweight children: the food industry or parents (Schor, 2004). Health advocates focus on the vast amount of advertising promoting unhealthy food to children, whereas the food industry points to parents who refuse to set limits for their children (on television viewing and unhealthy eating) or who simply do not understand enough about health to teach their children the importance of healthy eating and an active lifestyle. To our knowledge, no research has measured television viewing, parental influence and diet variables together to empirically assess the relative influence and interaction between these factors. In the present research, we begin to disentangle this complex relationship, and provide information to assist in the development of solutions to this critical health issue.

Development of food preferences

Individuals' food preferences (i.e., their disposition to select one food over another) play a major role in actual diet, whether healthy or unhealthy (IOM, 2006). Food preferences develop primarily through learning processes (Birch, 1999). Humans possess an innate preference for sweet, high-fat and salty foods, and a reluctance to try unfamiliar foods, however, early experiences are critical in shaping individual food preferences. Children learn about foods they like or dislike by being exposed to a variety of foods and observing and experiencing the consequences and rewards of consuming those foods.

Research points to perceived taste as the most important determinant of healthy and unhealthy food preferences, and evaluations of food taste can also be acquired through learning processes (IOM, 2006). Adults cited taste as the foremost reason that they chose to eat most foods (Glanz, Basil, Maibach, Goldberg & Snyder, 1998). Taste preferences for fruits and vegetables, together with their availability in the home, were the strongest predictors of fruit and vegetable consumption among adolescents (Neumark-Sztainer, Wall, Perry & Story, 2003). Numerous studies indicate that repeated exposure increases liking of disliked foods (see IOM, 2006), and information that a new food tastes good increased willingness to try the food (Pelchat & Pliner, 1995). In contrast, nutrition appears to be a secondary factor in food preferences (Glanz, et al., 1998).

Food preferences develop early (by age 2 or 3) and remain highly stable, at least through childhood (Skinner, Carruth, Bounds & Ziegler, 2002), and research has demonstrated the crucial role of parents in early learning of food preferences. Early parental modeling of both healthy and unhealthy food consumption, availability of different foods in the household, and parental controls over food consumption all influence food preferences (see Birch, 1999; IOM, 2006). As children move through middle childhood and adolescence, non-familial influences on eating behaviors increase (IOM, 2006). Accordingly, the quality of young people's diet declines during this period. Although these outside influences have not been studied extensively, peers, social institutions, the media and culture, in general, are all believed to play a role in the social transmission of food preferences (Rozin, 1996).

Potential influence of television

Children learn much about their social world vicariously, through observation of the media (Bandura, 2002). When watching television, children learn that calorie-dense foods that are high in fat and sugar taste great and are extremely rewarding to consume (Horgen, Choate, and Brownell, 2001). Food products comprise the most highly advertised category on television networks that children watch most; and 98% of advertised foods are of low nutritional value (Powell, Szczpka, Chaloupka, & Braunschweig, 2007). On average, children in the U.S. view 15 television food advertisements every day, or nearly 5,500 messages per year, that promote unhealthy food products (Federal Trade Commission, 2007). The most common themes in food advertising targeting children are great taste, fun, happiness and being "cool" (Folta, Goldberg, Economos, Bell & Meltzer, 2006). Unhealthy food references also appear extensively during television programming (Story & Faulkner, 1990).

Not surprisingly, research indicates a strong association between television viewing and unhealthy eating habits among children. Proven direct effects of television food advertising include greater recall, preferences and requests to parents for the products advertised (IOM, 2006). In addition, television viewing predicts unhealthy food preferences and higher body mass index (BMI) in children (Coon et al., 2001; Signiorelli & Lears, 1992; Signiorelli & Staples, 1997). Unhealthy snacking while watching television is common (Carruth, Goldberg, & Skinner, 1991) and viewing food advertising causes greater snack food consumption (Halford, Boyland, Hughes, Oliveira & Dovey, 2007; Harris, Bargh & Brownell, 2008). Quasi-experimental studies also demonstrate additional caloric intake associated with an increase in television viewing (Epstein et al., 2002; Robinson, 1999). In addition, food advertising may lead to greater adiposity among children and youth (IOM, 2006). These studies do not, however, definitively prove direct causal effects of food advertising on unhealthy food preferences and overall unhealthy diet. Accordingly, food industry proponents argue that the relationship between television viewing and unhealthy eating behaviors could be due to other factors, for example, parents' knowledge or concern about the importance of a healthy lifestyle (Young, 2003).

One potential mechanism through which food advertising may affect unhealthy eating habits could be through its effect on taste evaluations of advertised products. Although this hypothesis has not been tested directly, research in the fields of psychology and consumer behavior would predict this effect. Expectancy theory in social psychology posits that the quality of a person's experience with a stimulus is affected by expectations, beliefs and desires about that stimulus, in addition to qualities of the stimulus itself (Olson, Roese & Zanna, 1996). In the domain of food, numerous studies have demonstrated that expectancies about a food influence participants' actual taste experience (see Lee, Frederick & Ariely, 2006). For example, drinking Coke from a cup with a Coke logo increased ratings of the drink, as compared to drinking from a plain cup (McClure et al., 2004); reading that a nutrition bar contains "soy protein" (vs. "protein") reduced perceived taste of the bar (Wansink, Park, Sonka & Morganosky, 2000); and preschoolers liked the taste of foods and beverages significantly more when they were placed in McDonald's packaging, compared to the same foods in plain packaging (Robinson, Borzekowski, Matheson & Kramer, 2007). In an examination of the effects of food advertising on brand evaluations, children who saw an enjoyable food advertisement and then tried the food for the first time rated the brand more favorably than those who tried the new food before viewing the advertisement (Moore & Lutz, 2000). Viewing enjoyable television advertising for unhealthy food, therefore, is also likely to lead to more positive taste experiences when those foods are consumed, that could, in turn, lead to long-term negative effects on actual diet.

Potential solutions

In spite of the need for additional research, parents, legislators and health advocates are becoming concerned and increasingly ask the question, "How do we protect children against the unhealthy influence of television and food advertising?" Proposed solutions fall into three broad categories: 1) public service announcements and other media messages to communicate to children the importance of eating healthy foods; 2) parent-child communication and media literacy education to teach children to defend against unwanted advertising effects; and 3) reductions in children’s exposure to unhealthy messages on television, either through parental restrictions on the amount of television that children view or restrictions on the amount of advertising for unhealthy products presented on children's television. The evidence on the efficacy of most of these approaches, however, is inconclusive.

In support of the first approach, public service media campaigns have been used successfully to address other children’s health issues, including physical inactivity among youth (the CDC’s “VERB” campaign) and tobacco use (the American Legacy Foundation “truth” campaign). It may be more difficult, however, to change diet through pro-social media. There is little evidence that greater knowledge about nutrition leads to change in actual dietary behavior, among children or adults (IOM, 2006). In a meta-analysis, the association between nutrition knowledge and dietary behavior was found to be weak (Axelson, et al., 1985). In addition, there is some evidence that children may view "taste" and "healthiness" as opposites (Baranowski, et al., 1993): In an experimental study, children indicated that they liked the taste of a new drink less when it was labeled as "healthy" (Wardle & Huon, 2000). Among adolescents, however, concerns about health and benefits of healthy eating were associated with greater perceived taste of fruits and vegetables (Neubark-Sztainer, et al., 2003) and greater willingness to try foods labeled as nutritious (McFarlane & Pliner, 1997). Even if nutrition messages in the media do encourage children to eat healthy foods, however, spending on public service campaigns will never approach the estimated $10 billion spent annually by the food industry to promote primarily unhealthy foods to children and youth (Brownell & Horgen, 2004).

Parent-child communication about the unhealthy messages in food advertising could be a more promising approach. Consumer development and communications research demonstrates that discussions about media between parents and children play an important role in how media affects children. These effects can be either positive or negative, depending on the content of both the media and the discussion. Parents who critically analyze media content with their children (also known as "negative mediation" or "instructive mediation", see Austin, 2001) help teach them to be more skeptical about what they see in the media and may increase children's ability to defend against the messages presented (Austin, Pinkleton & Fujioka, 1999; Boush, 2001). Parental endorsement of media content (or positive mediation), on the other hand, can have positive or negative effects, depending on the message in the media that is being endorsed. In the case of prosocial media ("Barney and Friends", for example), when child viewing is accompanied by positive mediation, prosocial learning increases (Singer & Singer, 1998). When the content of the media is negative, however, positive mediation increases negative outcomes. For example, Austin and Chen (2003) found that positive mediation was associated with higher levels of perceived desirability of images in alcohol advertising, more positive alcohol expectancies (as presented in alcohol advertising), and reduced skepticism about advertising in general. As the majority of messages on television endorse unhealthy eating behaviors (Powell et al., 2006; Story & Faulkner, 1990), positive mediation is likely to negative influence healthy eating outcomes.

Expectancy theory also predicts that early understanding of the negative aspects of unhealthy foods could reduce the effects of advertising on taste perceptions. For example, disclosing a secret ingredient (balsamic vinegar) in a new beer reduced liking of that beer only if participants knew what the ingredient was before they tasted the beer (Lee, Frederick & Ariely, 2006). If they were told the ingredient after tasting, however, it did not affect their evaluation of the taste. This finding highlights the importance of teaching children early about the negative aspects of the foods that look so enticing in the advertising.

Another recommended approach to teach children to defend against advertising influence is media literacy education in schools, designed to increase critical viewing skills and skepticism about the media and advertising. Media literacy skills in adolescents have been associated with a lower likelihood to smoke or susceptibility to future smoking (Primack et al., 2006). A media literacy training program with 3rd graders lead to less positive alcohol expectancies and desire to choose alcohol-branded products, especially when combined with information about alcohol advertising specifically (Austin & Johnson, 1997). Exposure to unhealthy food advertising, however, begins in preschool or before, and peaks in elementary school (Powell et al., 2007), highlighting the need for early media literacy education to counteract the effects of food advertising. And yet, media literacy education may not be feasible before elementary school, as most children cannot understand the persuasive intent of advertising until they are 7 or 8 years old (Kunkel et al., 2004). Little research has systematically evaluated the media literacy curricula used in elementary schools (Brown & Witherspoon, 2002; Kunkel et al., 2004), and, to our knowledge, no studies have documented the relationship between media literacy and food advertising effects.

In the face of inconclusive evidence about the efficacy of programs to counteract media influence, parents may be best advised to limit the amount of time their children spend watching television (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2006). Even this approach, however, is questioned by parents who fear that severely restricting media access will lead to a sense of deprivation that could make the restricted media even more attractive and influential (Schor, 2004). In addition, controlled media exposure may be required to teach children the skills needed to defend (i.e., inoculate them) against its influence.

Research objectives

To begin to address the important question of how to reduce the influence of television and food advertising on unhealthy diet, we examined food preferences and eating habits in young adults and the relative influence of parental mediation behaviors and amount of television viewing during childhood and adolescence. In the absence of longitudinal data, this retrospective approach has been used with college students to assess the influence of parental communication and prior experiences on eating behaviors (Puhl & Schwartz, 2003), alcohol-related beliefs and behaviors (Austin & Chen, 2003), and smoking attitudes and behaviors (Rudman, Phelan & Heppen, 2007).

Our first prediction, in line with previous research on factors that influence diet, is that the most direct influence on healthy and unhealthy diet will be perceived taste of healthy and unhealthy foods. As found in previous research, we do not expect that nutrition knowledge will be associated with actual diet.

-

H1a:

Perceived taste of healthy and unhealthy foods is related to greater consumption of healthy and unhealthy foods, respectively.

-

H1b:

Nutrition knowledge is not significantly related to consumption of health or unhealthy foods.

In addition, if advertising creates expectancies that affect individuals' taste experiences, then advertised foods will be perceived as tastier than similar foods with less advertising:

-

H1c:

Taste ratings for advertised foods will be higher than ratings for similar foods with lower levels of advertising.

Second, due to the highly persistent nature of food preferences, we predict that the relationship found by other researchers between television viewing and unhealthy diet in children will continue into adulthood. As a result, greater television viewing in childhood and adolescence will also be associated with unhealthy diet in young adults. We also predict that prior television exposure will predict greater perceived taste and enjoyment (i.e., the most common benefits promoted in children's food advertising) for food categories that are most highly advertised. In addition, as the influence of prior television exposure on diet and food attitudes is hypothesized to be due to advertising exposure, the relationship will be direct, and not mediated by parental influence factors.

-

H2a:

Television viewing in childhood and adolescence will predict unhealthy diet in young adults, mediated by greater perceived taste and enjoyment of advertised, unhealthy foods.

-

H2b:

The relationship will not mediated by parental influence.

Finally, we hypothesize that parental communication will be related to diet, but that this relationship will vary according to the specific messages discussed. We hypothesize that both critical viewing (i.e., discussion about potentially harmful messages in the media) and food rules (i.e., discussion about healthy eating) will be negatively related to unhealthy diet. In addition, we predict that critical viewing and food rules will also affect expectancies about food taste and, therefore, will be negatively related to taste ratings for unhealthy food. In contrast, positive mediation is expected to be related to an underlying positive television viewing experience (that also includes amount of television viewing). Television viewing experience will be related to both higher perceived taste of unhealthy foods and unhealthy diet. Parental rules about television viewing are expected to reduce levels of television exposure. Although highly related to each other, we do not expect that parental rules, critical viewing and discussion about healthy eating represent an underlying parenting construct that correlates with both television viewing and unhealthy diet outcomes (as claimed by food industry proponents).

-

H3a:

Parental critical viewing and food rules will directly predict less positive taste evaluations of unhealthy foods and a less unhealthy diet.

-

H3b:

Positive mediation will be related to positive taste evaluations of unhealthy, advertised foods and unhealthy diet through its reinforcement of television viewing experience.

-

H3c:

Parental viewing rules will predict lower levels of television viewing.

In summary, we propose a model to determine whether prior television exposure predicts greater perceived taste and enjoyment of unhealthy, highly advertised foods and unhealthy diet in early adulthood. Parental rules and communication about television and food are expected to influence diet through their impact on associated outcomes. In addition, we will evaluate whether the same model also predicts healthy diet outcomes.

Method

College students at two different institutions in the Northeast, one private university and one state college, participated for class credit or payment. Participants completed an online survey on their own computer that took approximately 30 minutes.

Survey Measures

The survey included questions to assess current television viewing; childhood and adolescent viewing; memories of parental rules and attitudes about eating and television viewing; explicit attitude ratings of a variety of different foods on taste, good-for-you and enjoyment dimensions; and current consumption of different types of foods.

Current television viewing

Participants provided the total amount (hours and minutes) of television they watched every day in the previous week; 81% indicated that the previous week was comparable to their usual television viewing habits. Responses were added to obtain an estimate of current weekly television viewing.

Prior television viewing

Respondents indicated how many days per week they typically watched 3 different types of television programs when they were children (prime-time, cartoons and sports) and 7 different types of programs when they were in high school (prime-time, sports, news programs, music videos, late-night talk shows, daytime soap operas and Spanish-language television). Participants responded on a scale from 1 (never watched them) to 6 (watched them every day) (see Table 1). Individuals varied greatly in the specific types of television programs they usually watched, as a result, scores for most individual program types were positively skewed. To achieve a more normal distribution of viewing scores, we added scores for the individual program types to obtain one aggregate score each for childhood television viewing and high school television viewing.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics: Television viewing (N = 191)

| Television genres | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| When you were 12 years old and younger, how many days per week did you usually watch the following?† | |||

| Cartoons | 4.32 | 1.45 | 1–6 |

| Primetime TV (8 p.m. to 11 p.m., EST) | 3.59 | 1.55 | 1–6 |

| Sports programs | 1.93 | 1.20 | 1–6 |

| Total childhood television viewing | 9.84 | 2.96 | 3–18 |

| When you were in high school, how many days per week did you usually watch the following?†† | |||

| Primetime TV (8 p.m. to 11 p.m., EST) | 4.00 | 1.31 | 1–6 |

| News programs | 3.45 | 1.50 | 1–6 |

| MTV or VH1 | 3.20 | 1.74 | 1–6 |

| Late-night talk shows | 2.46 | 1.31 | 1–5 |

| Sports programs | 2.14 | 1.44 | 1–6 |

| Daytime soap operas | 1.48 | 1.09 | 1–6 |

| Spanish-language television | 1.47 | 1.06 | 1–6 |

| Total high school television viewing | 18.19 | 5.35 | 7–36 |

| Current television viewing (hours per week) | 6.61 | 8.12 | 0–44 |

Responses: 1 = never; 2 = less than once per week; 3 = once per week; 4 = 2 to 4 days per week, 5 = 5 or 6 days per week, 6 = every day

Food rules

The food rules scale was adapted from the childhood food rules developed by Puhl and Schwartz (2003). We utilized the 5 most common rules in their food encouragement subscale (see Table 2 for items). This subscale assessed parental rules that encouraged healthy eating behaviors. The original authors designed their items to assess potential influence of parental food rules on negative eating behaviors (e.g., binge eating or severe eating restraint) and did not measure food preferences or actual diet. The encouragement subscale, however, was not associated with negative eating behaviors, as were the other subscales. As in Puhl and Schwartz, participants indicated how often they heard these rules at home when they were children using a Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics: Parental influence scales (N = 191)

| Scale items | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| How often did you hear the following messages about food when you were a child?† | |||

| You had to clean your plate at each meal | 2.47 | 1.36 | 1–5 |

| If you put it on your plate, you had to eat it | 2.31 | 1.28 | 1–5 |

| You had to at least try or taste new foods | 3.56 | 1.12 | 1–5 |

| You always had to eat your vegetables at each meal | 3.37 | 1.32 | 1–5 |

| You could not have dessert until you finished your meal | 3.22 | 1.42 | 1–5 |

| Food rules scale | 2.99 | .96 | 1–5 |

| When you were younger, how often did your parents …†† | |||

| Say that they liked a product in a TV ad? | 2.25 | .76 | 1–4 |

| Say that they liked a person or character they saw on TV? | 2.57 | .81 | 1–4 |

| Agree with something on TV? | 2.71 | .62 | 1–4 |

| Say that something on TV often happens in real life? | 2.00 | .75 | 1–4 |

| Imitate something they saw on TV? | 1.80 | .80 | 1–4 |

| Positive mediation scale | 2.27 | .51 | 1–4 |

| When you were younger, how often did your parents …†† | |||

| Speak up when they saw something on TV that they disliked? | 3.12 | .88 | 1–4 |

| Say that something on a TV ad looked better than it really was? | 2.54 | .98 | 1–4 |

| Say that something on TV was not true? | 2.80 | .85 | 1–4 |

| Tell you more about something you saw on TV? | 2.82 | .81 | 1–4 |

| Talk with you about what ads are trying to do? | 1.93 | .92 | 1–4 |

| Disagree with something shown on TV? | 2.93 | .71 | 1–4 |

| Critical viewing scale | 2.70 | .59 | 1–4 |

| When you were younger, how often did your parents …†† | |||

| Tell you to turn off the TV when they saw what you were watching? | 2.74 | 1.07 | 1–4 |

| Set specific viewing hours for you? | 2.08 | 1.08 | 1–4 |

| Forbid you to watch certain programs? | 2.49 | 1.03 | 1–4 |

| Restrict the amount of time you could spend viewing? | 2.41 | 1.07 | 1–4 |

| Specify in advance what programs you could view? | 2.10 | 1.05 | 1–4 |

| Viewing restrictions scale | 2.36 | .85 | 1–5 |

Responses: 1 = never; 2 = rarely; 3 = sometimes; 4 = often; 5 = always

Responses: 1 = never; 2 = rarely; 3 = sometimes; 4 = often

Parental media influence

We assessed three different aspects of parental mediation that have been associated with children's interpretation of television messages: parents’ reinforcement of media messages (positive mediation), negative mediation of television content (critical viewing), and rules and restrictions about television viewing (viewing restrictions) (Austin, 2001), (see Table 2 for specific items). Items for the positive mediation and critical viewing scale were obtained from the positive and negative reinforcement scales used by Austin, Pinkleton & Fujioka (2000). Items from the restrictive mediation scale (Valkenburg, Krcmar, Peeters & Marseille, 1999) provided the viewing restrictions scale items. Participants indicated how often their parents commented on television content when they were younger or exhibited specific restrictive behaviors, and, as in prior studies, responses ranged from 1 (never) to 4 (often). All scales showed good internal reliability, including positive mediation (α = .73), critical viewing (α = .79), viewing restrictions (α = .86), and food rules (α = .79).

Food attitudes

Pre-testing was conducted to measure healthiness and advertising levels for a variety of foods. Respondents included staff affiliated with the obesity and eating disorders center and psychology graduate students at the private university. We identified 6 different food categories (of 5 foods each) that were differentiated by perceived healthiness (high, moderate and low) and level of advertising (higher vs. lower) (see Table 3). Healthy foods, overall, were much less advertised than unhealthy foods, therefore, it was not possible to match amount of advertising for foods at different levels of healthiness.

Table 3.

Food ratings pretest results (N = 48)

| Food categories | Advertising* | Healthiness** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. | |

| Healthy food: With more advertising Oatmeal, tuna, yogurt, milk, salad |

2.36 | .33 | 4.92 | .21 |

| Healthy food: With less advertising Apple, grapes, tomato, carrot, beans |

1.36 | .20 | 5.35 | .24 |

| Moderately healthy food: With more advertising Cereal, cracker, macaroni, cheese, juice |

3.02 | .54 | 3.62 | .52 |

| Moderately healthy food: With less advertising Bagel, almonds, popcorn, ham, avocado |

1.70 | .49 | 3.66 | .74 |

| Unhealthy food: With more advertising Cookie, chips, soda, candy, ice cream |

3.58 | .22 | 1.75 | .18 |

| Unhealthy food: With less advertising Butter, brownie, hot dog, bacon, pastry |

2.43 | .29 | 1.78 | .21 |

Advertising Ratings: 1 (no advertising) to 4 (a lot of advertising)

Healthiness Ratings: 1 (extremely unhealthy) to 6 (extremely healthy)

Participants in the present study rated each of the foods on taste, enjoyment and good-for-you (i.e., healthiness) dimensions. To achieve greater variability in reported attitudes, 10-point Likert scales were used. Even with the broader scales, scores for many of the individual foods continued to skew, either positively or negatively. As with television viewing variables, to normalize the distribution of scores, we aggregated the responses for individual foods in each category to obtain taste, enjoyment and healthiness scores for each of the 6 food categories (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics: Food attitudes and diet (N = 191)

| Aggregate attitude ratings | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taste ratings | |||

| Healthy food | 7.32 | .95 | 5.2–10 |

| With less advertising | 7.52 | 1.08 | 4.8–10 |

| With more advertising | 7.13 | 1.19 | 3.6–10 |

| Unhealthy food | 7.77 | 1.04 | 4.8–10 |

| With less advertising | 7.39 | 1.26 | 2.8–10 |

| With more advertising | 8.15 | 1.12 | 4.6–10 |

| Enjoyment ratings | |||

| Healthy food | 7.01 | 1.02 | 4.7–9.7 |

| With less advertising | 7.20 | 1.13 | 4.4–10 |

| With more advertising | 6.83 | 1.25 | 2.6–9.6 |

| Unhealthy food | 7.56 | 1.08 | 4.5–10 |

| With less advertising | 7.12 | 1.32 | 3.6–10 |

| With more advertising | 8.00 | 1.27 | 3.8–10 |

| Good-for-you (healthiness) ratings | |||

| Healthy food | 8.62 | .72 | 6.1–9.9 |

| With less advertising | 8.94 | .86 | 6.0–10 |

| With more advertising | 8.29 | .86 | 5.0–10 |

| Unhealthy food | 3.20 | 1.02 | 1.0–7.4 |

| With less advertising | 3.43 | 1.15 | 1.0–6.6 |

| With more advertising | 2.97 | 1.12 | 1.0–8.2 |

| Reported individual food consumption | M | SD | Range |

| How often do you eat the following foods?† | |||

| Healthy food consumption | 15.40 | 3.44 | 8–24 |

| Fruit | 4.24 | 1.12 | 2–6 |

| Vegetables | 4.62 | 1.13 | 1–6 |

| 1% or skim milk | 3.02 | 1.60 | 1–6 |

| Cheese or yogurt | 3.97 | 1.21 | 1–6 |

| Moderately healthy food consumption | 11.41 | 3.40 | 4–23 |

| Diet soda | 2.06 | 1.50 | 1–6 |

| Unsweetened cereal | 3.28 | 1.56 | 1–6 |

| 2% or whole milk | 2.70 | 1.68 | 1–6 |

| Fruit juice | 3.38 | 1.40 | 1–6 |

| Unhealthy food consumption | 12.07 | 2.87 | 5–21 |

| Sugar-sweetened soda or sports drinks | 2.70 | 1.56 | 1–6 |

| Sweets (cookies, cakes, ice cream, candy) | 3.65 | 1.08 | 1–6 |

| Sugared cereal | 2.70 | 1.11 | 1–5 |

| Potato chips or other salty snacks | 3.02 | 1.21 | 1–6 |

| Total consumption | 39.35 | 5.46 | 24–55 |

| Healthy diet (percent of total) | .39 | .07 | .20–.60 |

| Unhealthy diet (percent of total) | .31 | .06 | .14–.44 |

Responses: 1 = never; 2 = less than once per week; 3 = 1 to 3 times per week; 4 = 4 to 6 times per week; 5 = 1 or 2 servings per day; 6 = 3 or more servings per day

On all dimensions, ratings for moderately healthy foods fell between the ratings for healthy and unhealthy foods. To simplify the discussion, we report results for healthy and unhealthy foods in the remainder of the paper. In addition, enjoyment and taste were highly correlated for all foods (unhealthy foods: r = .88, p < .001; healthy foods: r = .87, p < .001) and exhibited the same relationship to other variables. As a result, we report taste, but not enjoyment, ratings in the remainder of the paper.

Food consumption behaviors

Finally, participants indicated how often they typically ate a variety of different foods. Responses ranged from 1 (never eat them) to 6 (eat 3 or more servings per day) (see Table 4). Total consumption scores were calculated for healthy foods (vegetables, fruits, low-fat milk, and cheese or yogurt), unhealthy foods (sweets, potato chips and other salty snacks, sugared drinks and sugared cereals), somewhat healthy foods (fruit juice, unsweetened cereal, diet soda, and whole milk dairy), and total consumption of all foods combined. To control for individual differences in total amount consumed, healthy and unhealthy diets were assessed by dividing total healthy and unhealthy food consumption scores by total consumption scores (for all healthy, moderately healthy and unhealthy foods).

Results and discussion

A total of 206 students participated: 90 at the public university and 116 at the private university. Complete data were collected from 193 participants. An additional 2 participants were eliminated due to extreme ratings (z-scores > ±3) on some of the food attitude measures. The sample was 70% female and 60% white, non-Hispanic. Participants also included 15% Hispanic, 14% Asian, and 11% black or other ethnicity. Ages ranged from 17 to 44 years (M = 19.1, SD = 2.4).

To assess overweight status, we utilized a measure from the U.S. Youth Risk Behavior survey (Centers for Disease Control, 2004) and asked participants to indicate their current weight status. According to their own assessment, approximately two-thirds of the sample (68%) indicated that they were normal weight, 17% reported being underweight (slightly or very), and 15% reported being overweight. Overweight status of 4-year college students, as assessed by self-reported height and weight in other studies, ranges from 20 to 30% (Huang, et al., 2003; Lowry, et al., 2000). The somewhat lower incidence of overweight in our sample may have been due to inaccurate assessments of weight status and could limit our ability to associate weight status with the other variables in our analysis. As a result, we do not attempt to make conclusions about the relationship between television viewing and obesity.

Food attitudes and diet

Participants reported consuming more healthy foods (on average, 4 to 6 times per week of each healthy category) than unhealthy foods (average of 1 to 3 times per week), t(191) = 9.99, p < .001. Individuals' total consumption of healthy and unhealthy foods, however, were not correlated (r = −.05, p = .49) and indicate that higher consumption of healthy foods did not always indicate lower consumption of unhealthy foods, or vice versa.

As predicted, perceived taste was associated with reported consumption: healthy food consumption was correlated with higher taste ratings for healthy foods, r = .28, p < .001, and lower taste ratings for unhealthy foods, r = −.18, p = .02. In contrast, unhealthy food consumption was highly correlated with taste ratings for unhealthy foods, r = .43, p < .001, but not significantly related to taste ratings for healthy foods, r = −.12, p = .11.

In contrast, assessments of food healthiness were not consistently related to healthy and unhealthy consumption. Healthy food consumption was positively correlated with perceived healthiness of healthy foods, r = .16, p = .03, and negatively with perceived healthiness of unhealthy foods, r = −.15, p = .05. Perceived healthiness of healthy and unhealthy foods did not, however, predict unhealthy food consumption (r = −.00, p = .99; r = .08, p = .28, respectively). Higher perceived healthiness of healthy foods was also associated with higher taste ratings for healthy foods (r = .35, p < .001). In contrast, healthiness ratings for unhealthy foods (i.e., perceived unhealthiness) was not significantly correlated with unhealthy food taste (r = .10, p = .18). Although prior research with children suggests that perceived healthiness of a food may be negatively related to taste (Baranowski, et al., 1993; Wardle & Huon, 2000), these findings with young adults demonstrate that perceived taste and healthiness may be positively related for healthy foods, and not at all related for unhealthy foods.

Overall then, the findings largely supported H1a and H1b. The best predictors of healthy and unhealthy diet were perceived taste of healthy and unhealthy foods. In addition, nutrition knowledge (as assessed by higher healthiness ratings for healthy foods and lower ratings for unhealthy foods) was not related to perceived taste or consumption of unhealthy foods. Higher consumption of unhealthy foods was significantly associated only with more positive attitudes about the taste of unhealthy foods. In contrast, nutrition knowledge did predict increased perceived taste and consumption of healthy foods.

Food attitudes and level of advertising

The difference between attitude ratings for foods with more versus less advertising was significant for all levels of healthiness and all types of attitudes. As predicted in H1c, unhealthy foods with higher levels of advertising were perceived as more tasty than unhealthy foods with lower levels of advertising, t(199) = 8.09, p < .001. For healthy foods, however, we found the opposite relationship: Those with lower levels of advertising were rated as more tasty than those with more advertising, t(199) = 4.27, p < .001.

Unexpectedly, we also found that different levels of advertising were associated with differences in perceived healthiness. In the pre-test, we had identified foods with similar levels of healthiness (according to our pre-test sample) that differed only by level of advertising. Among our young adult participants, however, both healthy and unhealthy foods with higher levels of advertising were perceived to be less healthy, (t(199) = 9.78, p < .001 and t(199) = 6.50, p < .001, respectively). We cannot determine from these data whether advertising caused these differing evaluations of taste and healthiness, or whether the differences were due to the specific foods evaluated. The results do suggest, however, that individuals could infer a relationship between advertising, healthiness and taste. For example, they might believe that healthy foods that are advertised do not taste as good as unadvertised healthy foods, or that advertised foods, in general, are not as healthy as unadvertised foods. If confirmed in further research, these findings indicate potential difficulties to effectively promote healthy food consumption through advertising.

Inter-relationship between television experience, parental mediation and diet

To test H2 and H3, we used structural equation modeling (SEM) to identify the relative contribution of television exposure and parental mediation on perceived food taste and relative healthy and unhealthy diet. Correlational analyses revealed that television exposure and parenting factors did not exhibit similar relationships to healthy and unhealthy food ratings and diet (see Table 5). Therefore, to simplify the analysis, we tested separate healthy and unhealthy models. In addition, we chose to include taste, but not perceived healthiness, ratings in our models. As discussed earlier, healthiness ratings were not significantly related to healthy or unhealthy consumption, nor were they significantly correlated with most television viewing and parental communication measures (see Table 5). As a result, when included in the models, most paths to and from healthiness ratings were not significant, and we chose to exclude them from the analysis.

Table 5.

Zero-order correlations between television viewing, parental influence, food ratings, and diet (N=191)

| Television Exposure | Communicating Limits | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current | Child | High School |

Positive Mediation |

Critical Viewing |

Viewing Restrictions |

Food Rules |

|

| Television viewing | |||||||

| Current | --- | ||||||

| Child | .29*** | --- | |||||

| High school | .46*** | .63*** | --- | ||||

| Parental influence | |||||||

| Positive mediation | .21** | .33*** | .40*** | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Critical viewing | .03 | −.07 | .06 | .42*** | --- | --- | --- |

| Viewing restrictions | .01 | −.23** | −.08 | .14 | .48*** | --- | --- |

| Food rules | .02 | −.11 | −.08 | .11 | .20** | .44*** | --- |

| Taste | |||||||

| Healthy food | .06 | −.05 | −.04 | .15* | .20** | .19** | .21** |

| Unhealthy food | .22** | .29*** | .26*** | .10 | −.10 | .01 | −.12 |

| Good-for-you | |||||||

| Healthy food | .07 | .04 | .03 | .15* | .08 | .10 | .08 |

| Unhealthy food | −.03 | −.03 | −.01 | .03 | .04 | .10 | −.10 |

| Healthy diet | −.17* | −.32*** | −.38*** | −.16* | .03 | .04 | .16* |

| Unhealthy diet | .15* | .25*** | .25** | .01 | −.23** | −.15* | −.22** |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Model specification

A latent variable was used to represent television viewing experience that included childhood and high school television viewing and positive mediation. Independent variables included food rules, television viewing restrictions, and parental critical viewing. As the viewing restrictions scale, displayed unacceptable kurtosis, data for that variable were transformed (logX / (1-X)) to achieve a normal distribution. Modeling utilized maximum likelihood estimates and estimated the covariance matrix.

Our first model specification required two minor adjustments to the originally hypothesized relationships between parental influence and television viewing variables. First, the original path from parental restrictions to television viewing experience was changed to predict only childhood television viewing. As predicted in H3c, viewing restrictions was negatively correlated with childhood television viewing; however, the hypothesized relationship between viewing restrictions and other television experience variables (i.e., high school viewing and positive mediation) was not significant (see Table 5). It appears that parents who do not approve of television may be more effective at limiting their younger children’s television viewing than that of their teenagers. We also added a path from critical viewing to positive mediation to improve the model fit. Although not predicted, this relationship is in line with other analyses that have found positive mediation and critical viewing to be correlated; they both may reflect an underlying measure of parental discussion about television (Austin & Pinkleton, 2001). As expected, critical viewing, viewing restrictions and food rules were all related to each other and, together, may indicate an overall parenting style to discuss expectations and limits.

Unhealthy diet model

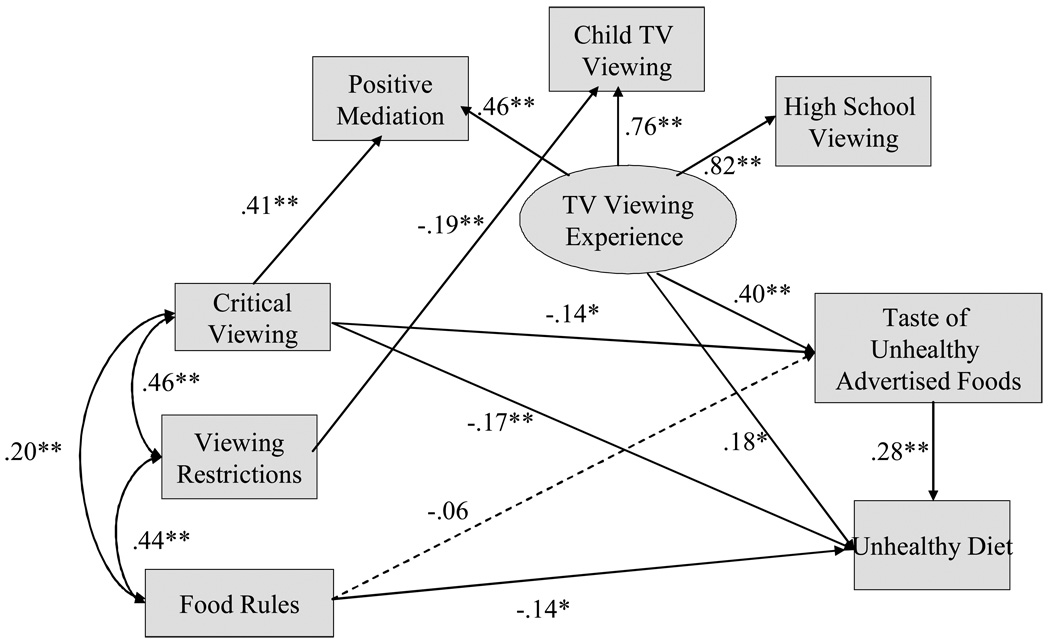

To examine the potential unhealthy influence of television food advertising, we first specified the model to predict taste of unhealthy, highly advertised foods and unhealthy diet (see Figure 1). Goodness-of-fit indicators showed that the data fit the model, χ2(13, N = 191) = 12.2, p = .51; RMSEA = .00 (90% CI = .00 to .07); CFI = 1.00. Multivariate normality was acceptable (Mardia's normalized coefficient = 4.56). All standardized regression coefficients indicated the expected relationships between variables, and the only insignificant path led from food rules to taste of unhealthy, advertised foods.

Figure 1. Model of unhealthy diet.

Note: Coefficients are standardized betas. Significant paths are designated by solid lines (*p < .05; **p < .01). Measured variables are depicted by rectangular boxes and latent constructs by ovals.

As predicted in H2a and H3b, greater television viewing experience was associated with a higher aggregate taste rating for unhealthy advertised foods which, in turn, was associated with a more unhealthy diet. Television experience was also directly related to a more unhealthy diet, however, further analysis revealed that taste partially mediated this relationship: An alternative model without the taste variable resulted in a stronger direct relationship between viewing experience and unhealthy diet (β = .29, p < .01 for the direct relationship vs. β = .18, p < .05 when taste was included as a mediator). Food rules and parental critical viewing also contributed independently to unhealthy diet, and critical viewing was related to lower perceived taste of unhealthy advertised foods. These findings partially support H3a: parents who are critical of the messages presented in food advertising can reduce television influence. Food rules did not, however, directly predict perceived taste of unhealthy, highly advertised foods, as hypothesized.

Alternative models

To further examine the potential influence of television food advertising on unhealthy diet we tested two alternative versions of the unhealthy diet model. In the first alternative, we assessed whether taste ratings for unhealthy foods that are not heavily advertised also partially mediated the relationship between television viewing experience and unhealthy diet. This model also fit the data, χ2(13, N = 191) = 10.50, p = .65; RMSEA = .00 (90% CI = .00 to .06); CFI = 1.00. As in the original model, the taste of unhealthy foods with less advertising was related to both television viewing experience (β = .20, p < .05) and unhealthy diet (β = .26, p < .01). In this model, however, the direct relationship between television viewing experience and unhealthy diet did not differ from the version without taste rating as a mediator (β = .29, p < .01 in the unmediated model). In addition, parental critical viewing was not related to perceived taste of unhealthy foods with less advertising (β = −.03, ns). These results further support our hypothesis that exposure to advertising messages on television directly contribute to unhealthy diet by increasing perceived taste of the unhealthy foods advertised, and that parents who question television messages can moderate this influence. Television viewing experience, however, also appears to directly predict a more unhealthy diet, beyond its influence on perceived taste of advertised foods.

In the second alternative model, we examined whether the relationship between television experience and unhealthy diet was mediated by an underlying parenting style to communicate limits and expectations that influenced both outcomes. In this version, we added a latent variable that included food rules, critical viewing and viewing restrictions. This model did not fit the data, χ2(16, N = 191) = 36.71, p < .01; RMSEA = .08 (90% CI = .05 to .12); CFI = .94. Therefore, this alternative explanation for the relationship between television viewing and unhealthy eating was not supported by the data, as predicted by H2b.

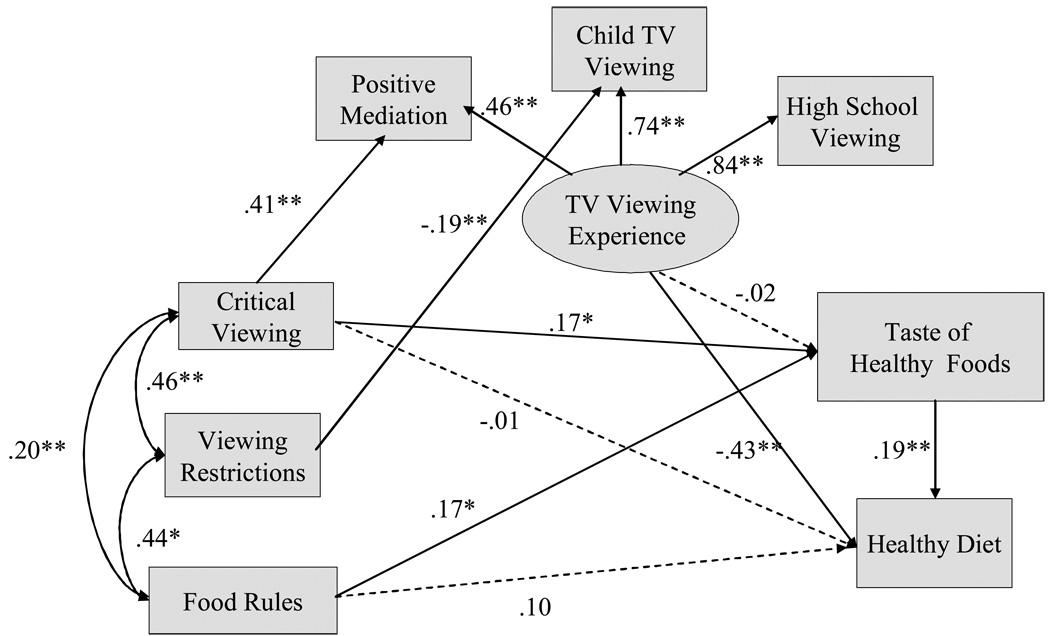

Model to predict healthy diet

We then applied the unhealthy diet model to predict healthy diet, replacing taste of unhealthy foods with taste of healthy foods (see Figure 2). This model also fit the data, χ2(13, N = 191) = 9.60, p =.73; RMSEA =.00 (90% CI = .00 to .05); CFI = 1.00. As in the unhealthy diet model, taste of healthy foods and television viewing experience directly predicted healthy diet. In this model, however, the relationship between television experience and taste of healthy foods was near zero. In addition, both food rules and critical viewing predicted taste of healthy foods, but did not directly predict healthy diet. These findings suggest that a more healthy diet is related to television viewing experience, but not through its effect on perceived taste of healthy foods. In contrast, parental communication about food and television appear to contribute to healthy diet through their influence on perceived taste of healthy foods. The strong negative relationship found between television viewing and healthy diet appears to be due to some factor not measured in this model, for example, perceived importance of a healthy lifestyle.

Figure 2. Model of healthy diet.

Note: Coefficients are standardized betas. Significant paths are designated by solid lines (*p < .05; **p < .01). Measured variables are depicted by rectangular boxes and latent constructs by ovals.

Discussion

Overall, these findings support our hypothesis that healthy and unhealthy diets are most directly related to the perceived taste of healthy and unhealthy foods. In addition, as expected, nutrition knowledge was not related to unhealthy diet, although it was indirectly related to healthy diet: Participants' ratings of the healthiness of healthy foods predicted greater perceived taste of those foods.

The results also support our hypothesis that the relationship between early television viewing and unhealthy eating found in previous research with children and adolescents continues into early adulthood. Past and present television viewing were correlated with both unhealthy and healthy diet in our college sample. In fact, eating behaviors were more highly correlated with childhood and adolescent viewing than current television viewing, although these results could be due to either greater influence from early television viewing or to unusual television viewing patterns while attending college.

The SEM analyses provide insights into potential reasons for the relationship between television viewing and diet. Both healthy and unhealthy diets were directly related to television viewing experience and may represent an underlying healthy (or unhealthy) lifestyle. The relationship between television viewing and unhealthy diet, however, was partially mediated by perceived taste of unhealthy, highly advertised foods, but not unhealthy foods with less advertising. In fact, the most significant path from television experience to unhealthy diet included taste of unhealthy, highly advertised foods. In contrast, the relationship between television viewing experience and the taste of healthy foods was near zero. These findings support our prediction that television viewing experience is associated with endorsement of the messages presented in children's food advertising (i.e., the unhealthy foods advertised taste great). We were surprised, however, to find no significant relationships between television viewing and attitudes about healthy food or ratings of food healthiness. The evidence consistently supports the conclusion that individuals who watch more television simply like the taste of unhealthy foods more, especially those that are highly advertised.

Also as predicted, parental influence measures moderated the relationship between television viewing and diet. Viewing restrictions and positive mediation were related to television viewing experience. Viewing restrictions, however, was only related to childhood viewing, which suggests the importance of limiting children's viewing early on, when it can be done effectively. In addition, lower viewing in childhood was associated with continued lower viewing in high school and college; we found no evidence of a rebound effect from early viewing restrictions.

Parental efforts to educate their children about food and television (i.e., food rules and critical viewing) also influenced healthy and unhealthy diet, but through different paths. Critical viewing was related to higher taste ratings for healthy foods and lower taste ratings for unhealthy, highly advertised foods. In contrast, food rules predicted higher taste ratings for healthy foods, but not unhealthy foods. We were surprised, however, that parental influence measures were not significantly related to nutrition knowledge. Overall, these findings support expectancy theory and suggest that parental efforts to counteract the unhealthy messages on television and teach healthy food preferences can influence their children's evaluations of food taste, and thus affect their healthy and unhealthy diet into adulthood. Both critical viewing and food rules were also directly related to unhealthy, but not healthy diet (in addition to their influence on taste preferences). Although we did not predict this relationship, perhaps parental communication can also teach children how to refrain from unhealthy eating, in spite of taste preferences for unhealthy foods.

Finally, the data did not support the alternative hypothesis, suggested by food industry proponents, that television viewing itself has no direct effect on unhealthy diet and that the relationship between television viewing and diet can be explained by a more permissive parenting style that allows children to watch less television and eat more unhealthy foods.

General Discussion

These findings provide insights into the potential effectiveness of solutions currently under discussion to counteract the unhealthy influence of television on children’s diets, including media interventions to teach children the importance of healthy eating and to defend against advertising influence, as well as efforts to reduce children’s exposure to unhealthy messages on television. The findings also suggest the need to clarify objectives when discussing alternative interventions to increase "healthy eating". Healthy versus unhealthy food consumption appear to have different underlying causes and improving one will not necessarily improve the other. Therefore, we discuss the potential for interventions to increase healthy consumption and/or reduce unhealthy consumption.

Implications for media interventions

The IOM (2006) recommends social marketing programs that use television and other media to promote the consumption of healthy foods, including fruits and vegetables. To support this initiative, the Better Business Bureau (BBB, 2006) announced a partnership with many of the largest children’s food advertisers to “shift the mix of advertising messages to children to encourage dietary choices and healthy lifestyles”. In support of this approach, we did obtain evidence that nutrition knowledge increased healthy diet. We also found, however, that increased advertising for healthy foods was associated with lower perceived taste for those foods and lower perceived healthiness. We cannot determine the direction of causality of these findings, however, they do suggest that efforts to advertise healthy foods must be closely monitored to ensure that they do not backfire and lead to reduced preferences for healthy foods that are advertised. Based on these data, the most effective message to increase healthy food consumption may be to promote the taste of healthy foods, and not emphasize their nutritional value.

Additionally, for the participants in our study, nutrition knowledge was not associated with a less unhealthy diet. It appears that most of our college-educated sample understood that many of the foods they were eating were unhealthy, but that knowledge was not related to lower unhealthy food consumption. As a result, pro-nutrition messages in the media and advertising for healthy foods appear unlikely to reduce consumption of unhealthy foods. We are not aware of any media campaigns to encourage reduced consumption of unhealthy foods. If done appropriately for a youth target (e.g., the "truth" anti-tobacco campaign), however, such a message may have a more significant effect on unhealthy diet.

This research also supports the potential for parents to encourage healthy eating in two ways: First, teaching children to question the unhealthy messages in the media reduced the influence of television viewing on unhealthy diet and perceived taste of unhealthy, advertised foods. It did not, however, eliminate the influence altogether. Second, critical viewing and food rules were related to higher perceived taste of healthy foods that led to greater consumption of healthy foods. These measures may correlate with parental efforts to model healthy eating and encourage their children to eat a variety of healthy foods (efforts that have been shown to increase healthy diet in children) (Birch, 1999). Future models should include specific measures to assess these parenting factors.

Parents and legislators also urge schools to implement media literacy curricula in elementary schools to teach children how to defend against the harmful effects of advertising (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2006; Brown, 2001; Harris, 2004). Our findings do not directly address the potential effectiveness of media literacy curricula; however, we question whether the traditional media literacy programs taught in elementary schools can effectively counter the influence of food advertising on unhealthy diet. Media literacy effects may differ depending on the child's stage in the product usage decision-making process and the specific skills taught in the media literacy program. For example, a large evaluation of a state-wide tobacco literacy program among adolescents found that non-smokers and smokers were affected differently (Pinkleton et al., 2007). For those who had never smoked, media literacy training affected their attitudes in the early stages of the smoking decision-making process; they reported that tobacco ads were less realistic, smoking was portrayed as less desirable, and smokers were less like them than those who did not participate in media literacy training. Among smokers, however, media literacy training messages appeared to become integrated into their own personal experiences. As a result, media literacy training affected smokers' perceptions of peer norms, their identification with smokers in ads, and expectancies about the effects of smoking.

Current elementary school media literacy programs that focus on teaching children how to critically view and analyze television advertising may be most effective at altering perceptions of food advertising in the early stages of decision-making. By elementary school, however, food preferences are firmly established (Skinner et al., 2002), and most children have had substantial personal experience with the rewards of consuming unhealthy foods advertised on television. Therefore, new approaches may be required to teach nutrition media literacy. For example, a focus on counteracting perceived norms or increasing negative expectancies about unhealthy food consumption (i.e., that address later stages in the decision-making process) may be more effective among elementary-school children. In addition, parents and early caregivers,may be the most important teachers of nutrition media literacy training. This approach is supported by a media literacy nutrition education curriculum conducted with parents of preschoolers (Hindin, Contento & Gussow, 2004). Parents who participated in the curriculum demonstrated greater understanding, support for and ability to talk to their children about the potential harmful effects of food advertising.

Based on our findings, reducing children's exposure to unhealthy messages on television appears to be the most direct means to reduce unhealthy diet. The American Academy of Pediatrics (2006) recommends that parents limit children’s non-educational screen time to no more than 2 hours per day. Even 2 hours of children's television, however, exposes children to almost 10 unhealthy food advertisements per day (FTC, 2007). The American Psychological Association (Kunkel et al., 2004) and American Academy of Pediatrics (Shifrin, 2005) also recommend a ban on television advertising to children under age 7 or 8. Our findings support the need for such a ban continuing through, at least, elementary school. Exposure to television during childhood (up to 12 years old) was directly related to greater endorsement of the messages in unhealthy food advertising and long-term unhealthy diet, even after controlling for parental mediation. In the absence of a ban on unhealthy food advertising, the most prudent advice for parents may be to restrict the amount of commercial television that their children watch, beginning at an early age.

Future directions

It is important to note several limitations of the data and associated findings. First, all measures are self-reported by participants. As a result, self-presentation, or even self-deception, biases could lead to results that do not accurately portray participants’ actual behaviors or beliefs. Self–reports of behaviors with associated social norms and prescriptions, including eating, television viewing and weight, may be especially unreliable. In addition, since many of the measures rely on reports of parental behaviors when participants were younger, the analysis also assumes accurate memories and perceptions of occurrences from many years earlier. We do not, however, suspect that the direction of these biases would differ by individual. For food consumption measures, in particular, we assume most individuals will likely underreport unhealthy food and over-report healthy food consumed. As a result, we believe that the direction of influence, if not the actual magnitude, accurately reflects reality.

The food consumption methodology requires an additional caveat. Our scale asked participants to report number of servings consumed, but did not define serving size. As a result, differences in perceptions of serving size were not reflected in these data. In addition, we examined a college student population that may not be representative of all young adults, or even all college students. Finally, as with all correlational analyses, results reflect relationships between variables and cannot determine causation.

These findings begin to disentangle the complex relationship between television viewing, parental mediation and diet, however, important questions remain to be addressed in future research. For example, our model to predict healthy and unhealthy diet could be expanded. Additional factors, not measured in this analysis, are also likely to play an important role. For example, individual child factors and environmental influences also influence television viewing. A child’s temperament, self-restraint, or energy level, as well as the availability of activities other than television to occupy after-school or weekend hours, could affect television viewing in childhood and adolescence as much as parental rules and attitudes about television. As discussed, parental modeling of healthy diet and availability of healthy and unhealthy foods in the household are also likely to influence perceived food taste.

Experimental studies would help differentiate the effects of food advertising from the effects of unhealthy messages in programming and the potential unhealthy effect of television viewing, distinct from food messages. Longitudinal studies, as well, would quantify the effect of accumulated television exposure over time and control for other variables that also influence this complex relationship. Interventions to help parents counteract the unhealthy influence of television by limiting children’s exposure to television and promoting critical viewing should be developed and tested. In addition, as food companies begin to implement child-targeted campaigns to promote "healthy" food consumption, it will be necessary to compare the efficacy of taste versus nutrition messages, and those that encourage lower consumption of unhealthy foods on overall diet outcomes.

In summary, our results support concerns that television food advertising targeting children and adolescents contributes to the obesity crisis. We found that television viewing during childhood and adolescence was related to a more unhealthy diet in early adulthood. This relationship, however, was not explained by permissive parenting or knowledge about nutrition. Instead, the belief that unhealthy, highly advertised foods taste great, the message commonly promoted in children's food advertising, was most strongly associated with unhealthy diet in young adults. Parents who teach their children to question the messages they see on television may attenuate this relationship, but the direct relationship between prior television exposure and diet remained. In addition, efforts to increase healthy food consumption and nutrition knowledge appear unlikely to affect unhealthy food consumption. These findings reinforce the importance of efforts to limit children's and adolescents' exposure to messages that promote taste and enjoyment of unhealthy foods, either through reduced television viewing or restrictions on advertising for unhealthy foods.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Communications. Children, adolescents, and advertising. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):2563–2569. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin EW. Effects of family communication on children’s interpretation of television. In: Bryant, Bryant, editors. Television and the American Family. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 377–395. [Google Scholar]

- Austin EW, Chen YJ. The relationship of parental reinforcement of media messages to college students' alcohol-related behaviors. Journal of Health Communication. 2003;8:157–169. doi: 10.1080/10810730305688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin EW, Johnson KK. Effects of general and media-specific media literacy training on children's decision making about alcohol. Journal of Health Communication. 1997;2:17–42. doi: 10.1080/108107397127897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin EW, Pinkleton BE. The role of parental mediation in the political socialization process. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media. 2001;45:221–240. [Google Scholar]

- Austin EW, Pinkleton BE, Fujioka Y. The role of interpretation processes and parental discussion in the media's effects on adolescents' use of alcohol. Pediatrics. 2000;105:343–349. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelson ML, Federline TL, Brinberg D. A meta-analysis of food- and nutrition-related research. Journal of Nutrition Education. 1985;17:51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of mass communication. In: Bryant J, Zillman D, editors. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 121–154. [Google Scholar]

- Baranowski T, Domel S, Gould R, Baranowski J, Leonard S, Treiber F, Mullis R. Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption among 4th and 5th grade students: Results from focus groups using reciprocal determinism. Journal of Nutrition Education. 1993;25:114–120. [Google Scholar]

- Better Business Bureau. New food, beverage initiative to focus kids’ ads on healthy choices; Revised guidelines strengthen CARU’s guidance to food advertisers. 2006 Press release, 14 Nov. 2006. Accessed at http://www.bbb.org/alerts/article.asp?ID=728 on 8/16/07.

- Birch LL. Development of food preferences. Annual Review of Nutrition. 1999;19:41–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boush DM. Mediating advertising effects. In: Bryant J, Bryant JA, editors. Television and the American Family. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum Associates; 2001. pp. 397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Boush DM, Friestad M, Rose GM. Adolescent skepticism toward TV advertising and knowledge of advertising tactics. Journal of Consumer Research. 1994;21:165–175. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JD, Witherspoon EM. The mass media and American adolescents' health. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:153–170. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00507-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JA. Media literacy and critical television viewing in education. In: Singer DG, Singer JL, editors. Handbook of Children and the Media. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001. pp. 681–697. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell KD, Horgen KB. Food Fight: The Inside Story of the Food Industry, America’s Obesity Crisis, and What We Can Do About It. New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Carruth BR, Goldberg DL, Skinner JD. Do parents and peers mediate the influence of television advertising on food-related purchases? Journal of Adolescent Research. 1991;6(2):253–271. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Methodology of the youth risk behavior surveillance system. 2004 Accessed at www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5312.pdf on 6/12/07.

- Coon KA, Goldberg J, Rogers BL, Tucker KL. Relationships between use of television during meals and children’s food consumption patterns. Pediatrics. 2001;107(1):1–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Paluch RA, Consalvi A, Riordan K, Scholl T. Effects of manipulating sedentary behavior on physical activity and food intake. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2002;140:334–339. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.122395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Trade Commission. Bureau of Economics Staff Report. Children's Exposure to TV Advertising in 1977 and 2004. 2007 Accessed at www.ftc.gov on 10/22/2007.

- Folta SC, Goldberg JP, Economos C, Bell R, Melzer R. Food advertising targeted at school-age children: A content analysis. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2006;38:244–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2006.04.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Basil M, Maibach E, Goldberg J, Snyder D. Why Americans eat what they do: Taste, nutrition, cost, convenience and weight control concerns as influences on food consumption. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1998;98:1118–1126. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(98)00260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford JCG, Boyland EJ, Hughes G, Oliveira LP, Dovey TM. Beyond-brand effect of television (TV) food advertisements/commercials on caloric intake and food choice of 5–7-year-old children. Appetite. 2007;49:263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris RJ. A Cognitive Psychology of Mass Communication. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Harris JL, Bargh JA, Brownell K. The direct effects of television food advertising on eating behavior. 2008 doi: 10.1037/a0014399. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindin TJ, Contento IR, Gussow JD. A media literacy education curriculum for Head Start parents about the effects of television advertising on their children's food requests. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004;104:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horgen KB, Choate M, Brownell KD. Television food advertising: Targeting children in a toxic environment. In: Singer DG, Singer JL, editors. Handbook of children and the media. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001. pp. 447–462. [Google Scholar]

- Huang TTK, Harris KJ, Lee RE, Nazier M, Born W, Kaur H. Assessing overweight, obesity, diet and physical activity in college students. Journal of American College Health. 2003;52:83–86. doi: 10.1080/07448480309595728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. National Academy of Sciences, Committee on Food Marketing and the Diets of Children and Youth. In: McGinnis JM, Gootman J, Kraak VI, editors. Food marketing to children and youth: Threat or opportunity? Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel D, Wilcox BL, Cantor J, Palmer E, Linn S, Dowrick P. Report of the APA task force on advertising and children. 2004 Retrieved from www.apa.org/releases/childrenads.pdf on 11/22/04.

- Lee L, Frederick S, Ariely D. Try it, you'll like it: The influence of expectation, consumption, and revelation on preferences for beer. Psychological Science. 2006;17:1054–1058. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone S, Helsper EJ. Does advertising literacy mediate the effects of advertising on children? A critical examination of two linked research literatures in relation to obesity and food choice. Journal of Communication. 2006;56:560–584. [Google Scholar]

- Lowry R, Galuska DA, Fulton JE, Wechsler H, Kann L, Collins JL. Physical activity, food choice, and weight management goals and practices among U.S. college students. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;18:18–27. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure SM, Li J, Tomlin D, Cypert KS, Montague LM, Montagure PR. Neural correlates of behavioral preference for culturally familiar drinks. Neuron. 2004;44:379–387. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane T, Pliner P. Increasing willingness to taste novel foods: Effects of nutrition and taste information. Appetite. 1997;28:227–238. doi: 10.1006/appe.1996.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore ES, Lutz RL. Children, advertising and product experiences: A multimethod inquiry. Journal of Consumer Research. 2000;27:31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Perry C, Story M. Correlates of fruit and vegetable intake among adolescents: Findings from Project EAT. Preventive Medicine. 2003;37:198–208. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JM, Roese NJ, Zanna MP. Expectancies. In: Higgins ET, Kruglanski AW, editors. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. pp. 211–238. [Google Scholar]

- Pelchat ML, Pliner P. "Try it. You'll like it." Effects of information on willingness to try novel foods. Appetite. 1995;24:153–166. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(95)99373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell LM, Szczpka G, Chaloupka FJ, Braunschweig CL. Nutritional content of television food advertisements seen by children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2007;120:576–583. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primack BA, Gold MA, Land SR, Fine MJ. Assocation of cigarette smoking and media literacy about smoking among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl RM, Schwartz MB. If you are good you can have a cookie: How memories of childhood food rules link to adult eating behaviors. Eating Behaviors. 2003;4:283–293. doi: 10.1016/S1471-0153(03)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TN. Reducing children’s television viewing to prevent obesity: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282(16):1561–1577. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TN, Borzekowsi DL, Matheson DM, Kraemer HC. Effects of fast food branding on young children's taste preferences. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161:792–797. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.8.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozin P. Sociocultural influences on food selection. In: Capaldi ED, editor. Why We Eat What We Eat. Washington, DC: APA; 1996. pp. 233–263. [Google Scholar]

- Rudman LA, Phelan JE, Heppen JB. Developmental sources of implicit attitudes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33:1700–1713. doi: 10.1177/0146167207307487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schor JB. Born to Buy: The Commercialized Child and the New Consumer Culture. NY: Scribner; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shifrin D. Remarks at Federal Trade Commission Workshop, “ Perspectives on Marketing, Self-Regulation and Childhood Obesity”; July 14–15, 2005; Washington, DC. 2005. Accessed at www.saap.org/advocacy/washing/dr_%20Shifrin_remarks.htm on 11/14/05. [Google Scholar]

- Signorielli N, Lears M. Television and children’s conceptions of nutrition: Unhealthy messages. Health Communication. 1992;4(4):245–257. [Google Scholar]

- Signorielli N, Staples J. Television and children’s conceptions of nutrition. Health Communication. 1997;9(4):289–301. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JL, Singer DG. In: Barney & Friends as entertainment and education. Asamen JK, Berry G, editors. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 305–367. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner JD, Carruth BR, Bounds W, Ziegler PJ. Children's food preferences: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2002;102:1638–1647. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90349-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Story M, Faulkner P. The prime time diet: A content analysis of eating behavior and food messages in television program content and commercials. American Journal of Public Health. 1990;80(6):738–740. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.6.738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valkenburg PM, Krcmar M, Peeters AL, Marseillie NM. Developing a scale to assess three styles of television mediation: "Instructive mediation", "restrictive mediation", and "social coviewing". Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media. 1999;43:52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wansink B, Park SB, Sonka S, Morganosky M. How soy labeling influences preferences and taste. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review. 2000;3:85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, Huon G. An experimental investigation of the influence of health information on children's taste preferences. Health Education Research. 2000;15:39–44. doi: 10.1093/her/15.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young B. Does food advertising make children obese? International Journal of Advertising and Marketing to Children. 2002;4:19–26. [Google Scholar]