Abstract

This study examined whether a transactional interpersonal life stress model helps to explain the continuity in depression over time in girls. Youth (86 girls, 81 boys; M age = 12.41, SD = 1.19) and their caregivers participated in a three-wave longitudinal study. Depression and episodic life stress were assessed with semi-structured interviews. Path analysis provided support for a transactional interpersonal life stress model in girls but not in boys, wherein depression predicted the generation of interpersonal stress, which predicted subsequent depression. Moreover, self-generated interpersonal stress partially accounted for the continuity of depression over time. Although depression predicted noninterpersonal stress generation in girls (but not in boys), noninterpersonal stress did not predict subsequent depression.

Youth depression is a recurrent and chronic disorder that often portends ongoing distress and impairment (for a review, see Rudolph, Hammen, & Daley, 2006). Despite the well-known fact that past depression is the best predictor of future depression (e.g., Lewinsohn, Zeiss, & Duncan, 1989; Tram & Cole, 2006), little research directly investigates the mechanisms that underlie the continuity of depression. The goal of the present research was to investigate one possible mechanism. Drawing from transactional perspectives of psychopathology (Cicchetti, Rogosch, & Toth, 1994; Sameroff & MacKenzie, 2003) and interpersonal theories of depression (Coyne, 1976; Hammen, 1992, 2006; Joiner, Coyne, & Blalock, 1999), this research examined the hypothesis that depressed youth generate stress in their relationships that contributes to the continuity of depression over time (see Figure 1). More specifically, based on theory and research indicating that girls show particular vulnerabilities within their relationships (for a review, see Rudolph, in press), it was expected that interpersonal stress generation would more likely serve as a mechanism underlying depression continuity in girls than in boys.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized transactional life stress model explaining the continuity of depression over time.

Transactional Interpersonal Theories of Depression

Transactional perspectives of psychopathology posit that youth and their social contexts participate in dynamic interchanges over time, creating feedback loops that stimulate reorganization at both the individual and environmental levels (Cicchetti et al., 1994; Sameroff & MacKenzie, 2003). Consistent with these perspectives, interpersonal theories of depression suggest that depressed individuals act in ways that elicit rejection and stress in their relationships; these disturbances then perpetuate depression. For example, Coyne's (1976) pioneering theory articulates an escalating cycle of interpersonal disturbances and depressive symptoms. Depressed individuals are thought to engage in excessive efforts to seek reassurance from their relationship partners. These efforts provoke avoidance or rejection, which then confirm the depressed individuals' self-doubt and maintain their symptoms (Coyne, 1976; Joiner et al., 1999). Similarly, Hammen's (1991, 1992, 2006) stress-generation theory proposes that characteristics and behaviors of depressed individuals create stress and conflict in their relationships, thereby contributing to subsequent depression.

These theories share the view that individuals help to create the stressful interpersonal contexts that contribute to their future vulnerability to depression. These stressors may result directly from depressive symptoms (e.g., self-doubt, irritability) or from specific interpersonal characteristics and behaviors of depressed individuals (e.g., excessive reassurance seeking, dependency, insecure attachment; for a review, see Hammen, 2006). Consistent with these theories, research supports the role of relationship disturbances and interpersonal stress as an antecedent and, to a lesser extent, a consequence of depression in youth (for a review, see Rudolph, Flynn, & Abaied, 2007).

Relationship Disturbances as an Antecedent of Youth Depression

Relationship disturbances may heighten risk for depression for several reasons. Stressful interpersonal experiences likely interfere with the maturation of competencies that thrive in the context of healthy relationships, such as the formation of a positive sense of self and effective self-regulation capacities; negative self-appraisals and poor self-regulation may then foster feelings of worthlessness, negative affect, and other symptoms of depression (Cicchetti et al., 1994; Rudolph et al., 2007). For example, youth who experience frequent conflict with their parents or exclusion by their peers may internalize these experiences in the form of low self-worth. They also may come to believe that they are incapable of forming positive relationships and unable to change their circumstances, leading to hopelessness and consequent depression. Youth with relationship difficulties also fail to receive important provisions of healthy relationships, such as emotional support, intimacy, and validation, thereby increasing risk for depression (Rudolph, 2002).

Indeed, prospective research reveals that relationship disturbances predict future depression. Youth who experience low levels of peer acceptance/popularity (Kiesner, 2002; for a review, see Kistner, 2006), high levels of peer rejection (Nolan, Flynn, & Garber, 2003) and victimization (Olweus, 1993), difficulties in their close friendships (Allen et al., 2006), and romantic relationship stress (Monroe, Rohde, Seeley, & Lewinsohn, 1999; Rizzo, Daley, & Gunderson, 2006) show heightened depression over time. Disturbances in family relationships, such as lower perceptions of support and intimacy (Allen et al., 2006; Brendgen, Wanner, Morin, & Vitaro, 2005; Davies & Windle, 1997; Eberhart & Hammen, 2006; Stice, Ragan, & Randall, 2004) and heightened parent-child conflict (Sheeber, Hops, Alpert, Davis, & Andrews, 1997), also predict depressive symptoms. More broadly, stressful interpersonal events (Hankin, Mermelstein, & Roesch, 2007), including self-generated or dependent interpersonal stress (i.e., stressors to which youth contribute; Davila, Hammen, Burge, Paley, & Daley, 1995; Little & Garber, 2005), predict subsequent depression.

Interpersonal stress may act as an especially potent risk factor in girls. Compared to boys, girls are more invested in the quality of their close relationships and the judgments of others, as reflected in heightened connection-oriented social goals (e.g., maintaining relationships, resolving problems), more dependency, and greater social-evaluative concerns (for a review, see Rose & Rudolph, 2006). This heightened interpersonal engagement likely enhances girls' sensitivity to relationship disruptions, making them more prone to depression when faced with interpersonal stress (Cyranowski, Frank, Young, & Shear, 2000; Hankin & Abramson, 2001; Rudolph, in press).

Some research supports the idea that interpersonal stress poses a greater threat to emotional well-being in girls than in boys. Concurrent data show that general interpersonal episodic stress (Shih, Eberhart, Hammen, & Brennan, 2006), interpersonal loss or separations (Goodyer & Altham, 1991), interpersonal conflict (Rudolph & Hammen, 1999), and stressful life events in friendships and the peer group (Rudolph, 2002), are more strongly linked to depression in girls than in boys. Prospective studies of this sex difference are limited, but some research does link interpersonal stress more strongly with growth in depressive symptoms in girls than in boys (Hankin et al., 2007). Examining a more specific aspect of relationship disturbances, two studies showed that peer rejection predicted depression in girls but not in boys, specifically when girls had certain temperamental and social-cognitive characteristics (Brendgen et al., 2005; Prinstein & Aikins, 2004).

Relationship Disturbances as a Consequence of Youth Depression

Depression may undermine youths' relationships in several ways. Specific symptoms and behaviors of depressed youth may interfere with their expression of appropriate social competencies, and make interactions with depressed youth unrewarding or unpleasant. For example, anhedonia, fatigue, and hopelessness may limit youths' ability or motivation to initiate interactions, leading to social isolation. Irritability and emotion dysregulation may create tension in relationships. Depressed youths' negative self-focus (e.g., low self-worth, rumination) also likely makes it difficult for them to act as supportive and enjoyable relationship partners, thereby eliciting alienation or rejection.

Although the focus of less research than the interpersonal antecedents of depression, some studies show that youth depression predicts relationship disturbances over time. Specifically, depression predicts peer rejection (Little & Garber, 1995; cf. Prinstein, Borelli, Cheah, Simon, & Aikins, 2005), lower perceived peer acceptance/popularity (Kiesner, 2002; Kistner, David-Ferdon, Repper, & Joiner, 2006), declines in number (Rudolph, Ladd, & Dinella, 2007) and stability (Prinstein et al., 2005) of friendships, and poorer self-reported friendship quality (Prinstein et al., 2005; Rudolph et al., 2007). Moreover, depressive symptoms predict subsequent stress in romantic relationships (Hankin et al., 2007). Within the family, depression predicts lower perceived parental support (Needham, in press) and poorer quality family relationships (Lewinsohn, Rohde, Seeley, Klein, & Gotlib, 2003).

Depression may have more interpersonal costs for girls than for boys. Girls' peer relationships are grounded in the intimate exchange of feelings, self-disclosure, and validation; these qualities emerge in preadolescence and intensify in adolescence (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Compared to boys, girls face more parent-child conflict (Hill, 1988; Smetana, 1989) and perceive more parent anger (Laursen, 2005) and emotional intensity (Allison & Schultz, 2004) during disagreements. Girls also have a stronger interpersonal orientation than do boys (Gore, Aseltine, & Colten, 1993). Girls' relationships may, therefore, be more emotionally demanding and may require stronger emotion-regulation skills than those of boys. Depressive symptoms, which likely drain emotional resources, may, therefore, heighten stress in girls' relationships. For instance, lack of motivation and social withdrawal may impair girls' ability to act as supportive relationship partners, thereby undermining their friendships. Likewise, irritability may amplify tension within parent-child relationships. Although some symptoms may interfere with boys' relationships (e.g., fatigue or anhedonia may cause them to disengage from group-based activities characteristic of boys; Rose & Rudolph, 2006), boys' relationships likely place fewer emotional demands on youth and, in fact, boys' activities may even serve as a useful distraction from their symptoms. Thus, we hypothesized, that depression would be more strongly linked with the generation of stress in girls' than boys' relationships.

Few studies have examined sex differences in the stress-generating effect of depression. Some concurrent data link depression more strongly with self-generated interpersonal stress in girls than in boys (Rudolph et al., 2000; Shih et al., 2006). Focusing on a specific index of interpersonal stress—friendship disruption—two longitudinal studies revealed that depressive symptoms more strongly predicted poor friendship quality and declines in reciprocal friendships (Rudolph et al., 2007), as well as less stable best friendships (Prinstein et al., 2005), in girls than in boys. Depression-linked behaviors (e.g., excessive reassurance seeking; Prinstein et al., 2005) also contribute more strongly to poor quality friendships in girls than boys, suggesting that the relationships of depressed girls suffer more than those of boys. In adults, wives' but not husbands' depressive symptoms predict the subsequent generation of marital stress (Davila, Bradbury, Cohan, & Tochluk, 1997).

Transactional Models

Despite support for the role of interpersonal stress as a contributor to, and consequence of, depression in youth, few studies explicitly investigate transactional processes. In one study, Garber and colleagues (Garber, Keiley, & Martin, 2002) examined reciprocal influences between general life stress and depressive symptoms. Analyses revealed that initial levels of stress predicted levels of depression trajectories, but not growth in depressive symptoms. Because there was no significant variance in the growth of stress, the effect of depression on changes in stress could not be evaluated. In two multi-wave studies, Cole and colleagues (Cole, Nolen-Hoeksema, Girgus, & Paul, 2006) found evidence for both stress-exposure and stress-generation processes, again using a measure of general life stress. Finally, Davila and colleagues (1995) found that depressive symptoms predicted subsequent interpersonal conflict stress, which in turn predicted depressive symptoms.

The present study extended prior research in two critical ways. First, this study compared transactional stress processes within the interpersonal versus noninterpersonal domains. The stress-generation perspective holds that stress in relationships is particularly likely to account for the continuity of depression (Hammen, 2006). Only a few studies directly compare interpersonal versus noninterpersonal stress-generation and stress-exposure processes. Concurrent data reveal stronger links between depression and self-generated interpersonal than noninterpersonal stress (Rudolph et al., 2000; cf. Shih et al., 2006, although the latter study did not distinguish self-generated from independent noninterpersonal stressors). Another study revealed that changes in interpersonal but not achievement stressors mediated the concurrent sex difference in depressive symptoms (Hankin et al., 2007). Longitudinal analyses from the latter study also showed that stressors in certain interpersonal domains served as antecedents and consequences of symptoms (longitudinal links were not examined for noninterpersonal stressors). Thus, a small amount of research supports the more salient role of interpersonal than noninterpersonal stress in depression, but longitudinal data are limited.

Second, this study examined sex differences in transactional stress processes. Although separate studies implicate interpersonal disturbances as more potent precursors or consequences of depression in girls than in boys, most studies examine only one direction of effect, and none examines sex differences in the extent to which interpersonal stress accounts for the continuity of depression over time (for one relevant study in adults, see Davila et al., 1997). Understanding this sex difference may shed light on differing trajectories of depression in girls and boys over time.

Overview of the Present Research

The present study examined sex differences in a transactional stress model of depression (see Figure 1). According to this model, depression predicts the generation of stress, and exposure to this self-generated stress then predicts future depression. In particular, we anticipated that self-generated interpersonal (but not noninterpersonal) stress would more likely contribute to the continuity of depression over time in girls than in boys.

We investigated the proposed transactional stress model during late preadolescence through mid adolescence, a period of time when both life stress (Ge, Lorenz, Conger, Elder, & Simons, 1994; Rudolph & Hammen, 1999) and depression levels (Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler, & Angold, 2003; Hankin et al., 1998) begin to rise, particularly in girls. Youth participated in a three-wave study spanning a two-year period, allowing for the investigation of how depression and stress unfold over time. Semi-structured diagnostic interviews were administered to youth and their caregivers to assess depression. Life stress interviews also were administered to youth and their caregivers, and were coded using the contextual threat method. This state-of-the-art methodology uses specific contextual information about stressors to determine the amount of objective threat associated with events, thereby reducing bias created by subjective perceptions of stress. Moreover, this approach provides the opportunity to identify self-generated (i.e., dependent) life events, allowing for a true test of transactional processes.

Method

Participants

Participants in the present study included 167 youth (86 girls, 81 boys; 4th – 8th graders at Wave 1; M age = 12.41, SD = 1.19) and their female caregivers (88.6% biological mothers; 1.8% stepmothers; 4.2% adoptive mothers; 5.4% other) recruited from several Midwestern towns. The majority of the sample was white (77.8%); the remainder of the participants were African American (12.6%) or represented other ethnic groups and biracial youth (9.6%). Families represented a range of socioeconomic classes (16.7% below 30,000, 48.7% $30-59,999, 21.6% $60,000-89,999, and 13.0% over $90,000). Youth were selected for this study based on school-wide screenings with the Children's Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1981). Youth with a range of CDI scores were recruited, over-sampling slightly for youth with severe symptoms (15.8% of the screening sample, 20.3% of targeted youth, and 24.1% of recruited youth had scores > 18). Participants were recruited based on CDI scores, having a maternal caregiver in the home, and proximity (within one hour) to the university. Exclusion criteria included having a non-English speaking maternal caregiver and having a severe developmental disability that interfered with the ability to complete the assessment.

Youth whose families did and did not consent to participate in the study did not differ in sex, χ2(1) = .39, ns, ethnicity (white versus minority), χ2(1) = .02, ns, or CDI scores, t(280) = 1.11, ns. Participants (M = 12.41) were slightly, but not meaningfully, younger than nonparticipants (M = 12.65), t(275) = 2.28, p < .05. Relevant data (i.e., depression and stress scores) were available for 93.4% of the original sample at Wave 2 (W2), and 94.6% of the original sample at Wave 3 (W3). Youth without data at W2 or W3 did not differ from those with complete data in sex, χ2(1) = .96, ns, age, t(165) = .78, ns, ethnicity (white versus minority), χ2(1) = .61, ns, Wave 1 (W1) depression, t(165) = .43, ns, W1 dependent interpersonal stress, t(165) = .77, ns, or W1 dependent noninterpersonal stress, t(165) = .32, ns.

Procedures

All of the procedures for this study were approved by the university's Institutional Review Board. Families were recruited through phone calls to the primary female caregivers. Interested families completed an in-person, three- to four-hour initial assessment. Caregivers provided written informed consent, and youth provided written assent. Youth and their caregivers were then interviewed separately. Two different interviewers conducted the diagnostic and life stress interviews to avoid biases during the interviewing process. Two follow-up interviews were completed at one-year intervals. To compensate families for their time, caregivers were given a monetary reimbursement and youth were given a gift certificate at each assessment.

Measures

Depression

Interviewers individually administered the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Epidemiologic Version-5 (K-SADS-E; Orvaschel, 1995) to youth and their caregivers to assess youth depression. Interviewers included a faculty member in clinical psychology, a post-doctoral student in clinical psychology, several trained psychology graduate students, and a post BA-level research assistant. All interviews were coded through consultation with a clinical psychology faculty member or post-doctoral student. Consensual diagnoses were assigned using a best-estimate approach (Klein, Ouimette, Kelly, Ferro, & Riso, 1994) to integrate information across the caregiver and youth report.

Interviewers used Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders criteria (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) to assign ratings of major depressive symptoms on a 5-point scale: 0 = No symptoms, 1 = Mild symptoms, 2 = Moderate symptoms, 3 = Diagnosis with mild to moderate impairment, and 4 = Diagnosis with severe impairment. Based on DSM-IV criteria, these ratings considered the number, severity, frequency, duration, and resulting impairment of the reported symptoms. Thus, subthreshold symptoms (i.e., mild or moderate) reflected the presence of symptoms that failed to meet one or more of these criteria (e.g., the youth had fewer than the required number of symptoms or had the required number of symptoms for less than the required duration). Separate ratings were assigned for each period of major depression (both diagnosable episodes and subthreshold symptoms) during the year preceding the interview, including the present. These ratings were then summed to create continuous depression scores for each wave of the study such that higher ratings reflect more severe symptoms within a single period and/or multiple periods of depression (for similar rating approaches, see Davila et al., 1995; Hammen, Shih, Altman, & Brennan, 2003; Hammen, Shih, & Brennan, 2004; Rudolph et al., 2000). Thus, these scores represent composite indexes of several different markers of depression severity. Validity of these scores was established through significant correlations with several self-report measures of depressive symptoms (rs = .24 - .45, ps < .01). Moreover, this continuous index of depression is consistent with contemporary conceptualizations, derived in part from taxometric analyses, that view depression as best represented by a dimensional continuum rather than a discrete category (Fergusson, Horwood, Ridder, & Beautrais, 2005; Hankin, Fraley, Lahey, & Waldman, 2005; Shih et al., 2006). Strong inter-rater reliability was found for the depression ratings (one-way random-effects intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] = .95).

At Wave 1, 12.0% of youth (8.6% of boys and 15.1% of girls) had experienced either moderate (consistent with a minor depressive episode) or diagnostic-level symptoms within the past year; an additional 5.4% (7.4% of boys and 3.5% of girls) experienced mild symptoms. At Wave 2, 14.5% of youth (11.7% of boys and 17.1% of girls) experienced either moderate or diagnostic-level symptoms within the past year; an additional 4.4% (3.9% of boys and 4.9% of girls) experienced mild symptoms. At Wave 3, 12.0% of youth (7.9% of boys and 15.9% of girls) experienced either moderate or diagnostic-level symptoms within the past year; an additional 4.4% (2.6% of boys and 6.1% of girls) experienced mild symptoms. Thus, although the sample was not severely depressed, a reasonable percentage of the youth experienced depressive symptoms during the study.

Life stress

Interviewers administered the Youth Life Stress Interview (Rudolph & Flynn, 2007), an adaptation of the Child Episodic Life Stress Interview (Rudolph & Hammen, 1999; Rudolph et al., 2000), separately to youth and their caregivers. Interviewers included several trained psychology graduate and advanced undergraduate students and a post BA-level research assistant. This semi-structured interview used the contextual threat method to determine the nature and intensity of episodic life stress experienced by youth during the preceding year (Brown & Harris, 1978). Standardized probes were used to elicit objective information about the occurrence of stressful events across several life domains (e.g., school, same- and opposite-sex peer relationships, parent-child relationships, health). Interviewers first asked a general open-ended question regarding youths' exposure to stressful events in the past year. Interviewers then provided prompts about specific stressful events within each domain (e.g., a parental divorce, end of a friendship, failing an exam, an illness). Follow-up questions were asked to elicit detailed information about each event, the timing and duration of the event, and objective consequences. Based on this information, interviewers presented a narrative summary of each event to a team of coders with no knowledge of the youth's diagnosis or subjective response to the event.

Integrating information from youth and caregivers, the coding team provided two ratings: (1) the objective stress or negative impact associated with the event for a typical youth in those circumstances, from 1 (No negative stress) to 5 (Severe negative stress); events with ratings of 1 were excluded; and (2) the extent to which the event was self-generated, or dependent on the youth's contribution, from 1 (Completely independent) to 5 (Completely dependent). Events with dependence ratings of 3 or above were categorized as dependent (Daley et al., 1997; Davila et al., 1995; Rudolph et al., 2000). The team also categorized each event as interpersonal (i.e., events that involved a significant interaction between the youth and another person or that directly affected the relationship between the youth and another person) or noninterpersonal (all other events). Because the present study focused on stress generation, two composite scores reflecting dependent interpersonal stress (e.g., ending a friendship) and dependent noninterpersonal stress (e.g., failing an exam because the youth did not study) were calculated by summing the stress ratings across all relevant events with a stress rating above 1. W1 dependent interpersonal stress scores ranged from 0 to 23, and W1 dependent noninterpersonal stress scores ranged from 0 to 13.5. To assess reliability, 160 life events were coded by two independent teams. High reliability was found for ratings of objective stress (ICC = .90) and dependence (ICC = .96), as well as for the categorization of event content (Cohen's k = .92).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 displays the means and standard deviations for depression and dependent stress at each wave. A multivariate repeated-measures analysis of variance was conducted with Sex as a between-subjects factor, and Wave as a within-subjects factor. This analysis yielded a significant main effect of Sex, F(3, 149) = 4.92, p < .01. Nonsignificant multivariate effects were found for Wave, F(6, 146) = .52, ns, and the Sex by Wave interaction, F(6, 146) = .31, ns. Follow-up univariate analyses revealed a significant main effect of Sex for dependent noninterpersonal stress, F(1,153) = 13.46, p < .001, with boys (M = 3.74, SD = 3.94) generating higher levels of noninterpersonal stress than girls (M = 2.36, SD = 2.66). No sex differences were found for depression, F(1,155) = .93, ns, or dependent interpersonal stress, F(1,153) = 1.11, ns. The absence of sex differences in these variables is likely due to the fact that these differences tend to emerge during middle adolescence (about age 13; e.g., Costello et al., 2003; Ge et al., 1994; Rudolph & Hammen, 1999), and more than half of the present sample was younger than 13 years old.

Table 1. Means and Standard Deviations of the Variables.

| Measures | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | Boys | |

| Depression | .52 (1.23) | .35 (.99) | .57 (1.21) | .36 (.93) | .46 (.98) | .39 (1.36) |

| Dependent Interpersonal Stress | 3.02 (3.57) | 3.61 (4.66) | 2.98 (3.44) | 3.17 (4.43) | 2.66 (3.03) | 3.06 (5.18) |

| Dependent Noninterpersonal Stress | 2.19 (2.45) | 3.37 (3.58) | 2.35 (2.71) | 3.91 (4.25) | 2.60 (2.82) | 3.58 (3.91) |

Table 2 presents intercorrelations among the measures for girls and boys. As expected, these correlations revealed significant stability in depression across waves, with the exception of W1 to W3 in boys. Fishers r-to-Z transformations revealed that the W2-W3 stability coefficient was significantly higher in girls than in boys, Z = 2.15, p < .05; the W1-W2 and W1-W3 coefficients were marginally higher in girls than in boys, Zs = 1.57 and 1.48, ps < .10, one-tailed. In girls but not in boys, W1 depression was significantly associated with W2 dependent interpersonal stress, and W2 dependent interpersonal stress was significantly associated with W3 depression. These associations were significantly stronger in girls than in boys, Z = 2.26, p < .05, and Z = 2.65, p < .01, respectively. In girls, W1 depression also was significantly associated with W2 dependent noninterpersonal stress (this association was significantly different in girls and boys, Z = 3.34, p < .01), although W2 dependent noninterpersonal stress was not associated with W3 depression. No significant associations were found between depression and dependent noninterpersonal stress in boys.

Table 2. Intercorrelations Among the Variables.

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Wave 1 Depression | --- | .33** | .12 | .04 | -.02 | .06 | .01 | -.20 | .01 |

| 2. Wave 2 Depression | .53*** | --- | .44*** | .12 | .31** | .11 | -.08 | .02 | .18 |

| 3. Wave 3 Depression | .34** | .67*** | --- | .15 | .01 | .20 | .01 | -.16 | .01 |

| 4. Wave 1 Dependent Interpersonal Stress | .18 | -.01 | -.05 | --- | .42*** | .54*** | .41*** | .35** | .51*** |

| 5. Wave 2 Dependent Interpersonal Stress | .30** | .47*** | .42*** | .31** | --- | .49*** | .09 | .34** | .40** |

| 6. Wave 3 Dependent Interpersonal Stress | .13 | .16 | .11 | .32** | .28* | --- | .08 | .14 | .53*** |

| 7. Wave 1 Dependent Noninterpersonal Stress | -.03 | -.12 | -.14 | .39*** | .16 | .36** | --- | .21 | .07 |

| 8. Wave 2 Dependent Noninterpersonal Stress | .33** | .25* | .04 | .17 | .29** | .18 | .18 | --- | .35** |

| 9. Wave 3 Dependent Noninterpersonal Stress | .01 | .10 | .01 | .37** | .29** | .51*** | .44*** | .33** | --- |

Note. Intercorrelations presented above the diagonal are for boys; intercorrelations presented below the diagonal are for girls.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Test of the Hypothesized Model

Path analyses using AMOS Version 7.0 (Arbuckle, 2006) were conducted to examine the extent to which self-generated stress contributed to the continuity of depression over time. AMOS handles missing data using the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation method (Arbuckle, 1999). The first model evaluated whether W2 dependent interpersonal stress accounted for the continuity between W1 and W3 depression. The second model evaluated whether W2 dependent noninterpersonal stress accounted for the continuity between W1 and W3 depression. For each model, dependent stress and depression were represented by manifest variables. The models included W1 depression as a predictor of W2 dependent stress, and W2 dependent stress as a predictor of W3 depression. Each model adjusted for the relevant type of dependent stress at W1. The path from W1 to W3 depression also was included in each model to allow for an examination of the continuity of depression after accounting for dependent stress.

To test the hypothesis that the proposed transactional life stress model differed in girls and boys, we conducted multi-group comparison analyses to examine the invariance of the models across sex. Specifically, we compared a constrained model (the paths of interest were set to be equal across sex) and an unconstrained model (the paths of interest were allowed to vary across sex). Several fit indices were examined, including the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), the Incremental Fit Index (IFI; Bollen, 1990), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Steiger, 1990). For the CFI and IFI, values above .90 indicate good model fit (Bentler, 1990; Bollen, 1990; Kline, 1998). For the RMSEA, values below .05 indicate an excellent model fit, whereas values of .05 to .08 indicate a good fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). In addition, the χ2/df ratio was examined; ratios of less than 2.5 or 3 reflect a good model fit (Kline, 1998). Chi-square difference tests were used to compare the fit of the constrained and unconstrained models.

Interpersonal stress

Consistent with the expectation that the transactional interpersonal stress model would better characterize girls than boys, a chi-square difference test, Δχ2(2) = 7.37, p < .05, revealed that the unconstrained model, χ2(6) = 7.49, ns, χ2/df = 1.25, CFI = .96, IFI = .97, RMSEA = .04, fit significantly better than the constrained model, χ2(8) = 14.86, p = .06, χ2/df = 1.86, CFI = .83, IFI = .87, RMSEA = .07. Examination of the squared multiple correlations (i.e., proportion of variance in W3 depression explained by W1 depression and W2 dependent interpersonal stress) indicated that the unconstrained model predicted 23% of the variance in W3 depression in girls, and 2% in boys (a medium-to-large effect size for the former and a small effect size for the latter; Cohen, 1992).

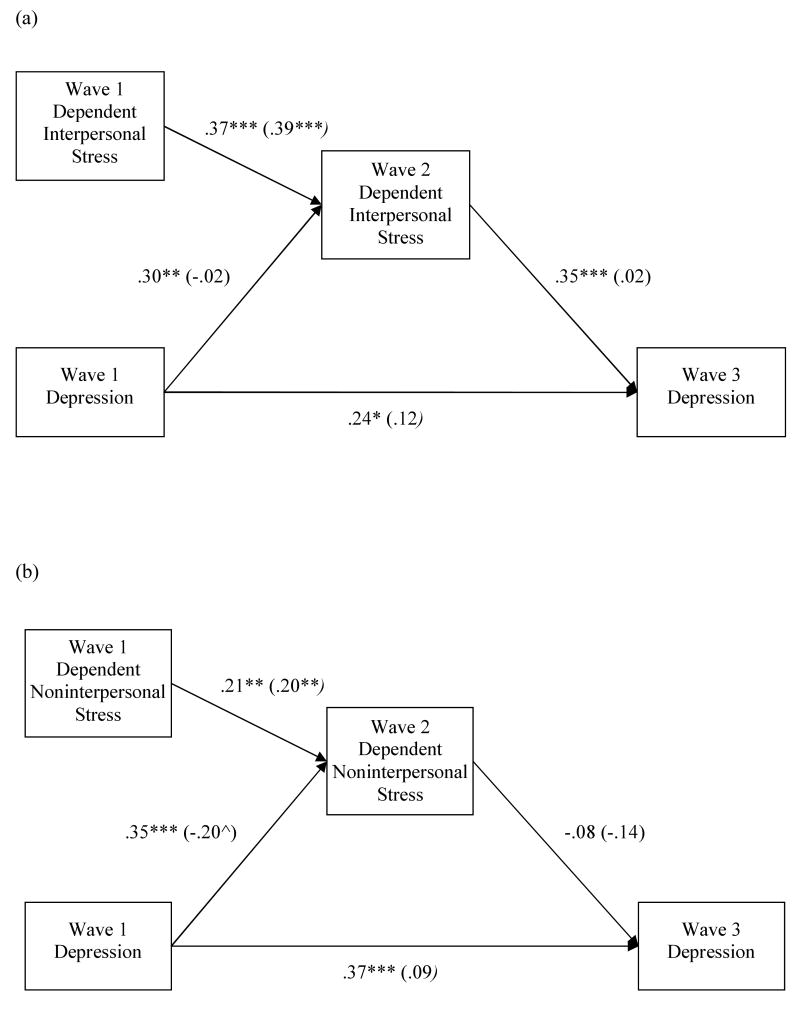

Figure 2a displays the standardized path coefficients for an unconstrained model in girls and boys. The stability path from W1 to W2 stress was constrained to be equal across groups because this path did not significantly differ in girls and boys. Following recommended guidelines (Baron & Kenny, 1986; Kenny, Kashy, & Bolger, 1998; MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002; Shrout & Bolger, 2002), several indicators were examined to evaluate mediation in girls (because all relevant paths were nonsignificant in boys, mediation was not examined). First, we examined the size and significance of the indirect effect (Sobel, 1982; 1986). As anticipated, W1 depression significantly predicted W2 dependent interpersonal stress, which significantly predicted W3 depression (see Figure 2a; indirect effect = .11, Z = 2.28, p < .05). Second, the significant total effect of W1 depression on W3 depression (β = .34, p < .01) was reduced once dependent interpersonal stress was included in the model, although it remained significant (β = .24, p < .05). Third, following Shrout and Bolger (2002), to quantify the strength of mediation we calculated an effect proportion (indirect effect/total effect). The effect proportion indicated that 32% of the total effect of W1 depression on W3 depression was accounted for by dependent interpersonal stress. Together, these indicators suggest that interpersonal stress generation partially mediated the continuity of depression over time.1

Figure 2.

Transactional life stress models depicting the observed pathways for (a) interpersonal stress, and (b) noninterpersonal stress. Coefficients without parentheses are for girls; coefficients in parentheses are for boys. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Noninterpersonal stress

A parallel set of analyses was conducted to examine a transactional noninterpersonal stress model. A chi-square difference test, Δχ2(2) = 9.60, p < .01, revealed that the unconstrained model, χ2(6) = 2.02, ns, χ2/df = .34, CFI = 1.00, IFI = 1.14, RMSEA = .00, fit significantly better than the constrained model, χ2(8) = 11.62, ns, χ2/df = 1.45, CFI = .74, IFI = .86, RMSEA = .05. Examination of the squared multiple correlations indicated that the model predicted 9% of the variance in W3 depression in girls, and 6% in boys (a small effect size for both; Cohen, 1992).

Figure 2b displays the standardized path coefficients for an unconstrained model in girls and boys. Again, the stability path from W1 to W2 stress was constrained to be equal across groups because this path did not significantly differ in girls and boys. We examined several indicators of mediation in girls (because of the nonsignificant paths in boys, mediation was not examined). In girls, W1 depression significantly predicted W2 dependent noninterpersonal stress; however, W2 dependent noninterpersonal stress did not significantly predict W3 depression (see Figure 2b; indirect effect = -.03, Z = -.71, ns). Not surprisingly, given the lack of a significant association between W2 dependent noninterpersonal stress and W3 depression, the significant total effect of W1 depression on W3 depression (β = .35, p < .01) was virtually unchanged when dependent noninterpersonal stress was included in the model (β = .37, p < .01). Together, these indicators suggest that noninterpersonal stress generation did not mediate the continuity of depression over time.2

Discussion

This study examined sex differences in the contribution of stress generation to the continuity of depression over time. Consistent with contemporary theoretical models emphasizing the interpersonal context of depression in girls (e.g., Cyranowski et al., 2000; Rudolph, in press), the findings indicated a self-perpetuating cycle of depression, interpersonal stress generation, and subsequent depression in girls but not in boys. This research broadens the stress-generation perspective by shedding light on key sex differences in transactional stress processes. Moreover, these results contribute to a relatively small body of research that directly examines the mechanisms underlying depression continuity (e.g., Davila et al., 1995; Potthoff, Holahan, & Joiner, 1995) and provide one possible explanation for the diverging developmental trajectories of depression in girls and boys (e.g., Ge, Conger, & Elder, 2001).

The Role of Self-Generated Interpersonal Stress in Depression Continuity

Using a sophisticated life stress assessment, which provided the opportunity to determine youths' contribution to events, and a contextual threat coding method, which minimized bias introduced by subjective appraisals of stress, this research revealed that depressed girls generated stressful interpersonal events that contributed to their future depression. Moreover, this self-generated interpersonal stress partially accounted for the continuity of depression over time. In contrast, depression neither precipitated nor resulted from self-generated interpersonal stress in boys.

Several factors may explain this self-perpetuating cycle of depression and interpersonal stress in girls but not in boys. Symptoms may directly damage girls' relationships by lessening their ability or motivation to engage in the intimate exchange and mutual support typically expected in female relationships, and by creating tension or conflict. For example, fatigue and lack of interest in social activities may cause girls to neglect their friendships and withdraw from their families. Irritability may cause girls to interact in ways that foster arguments and rejection. The normative social challenges that characterize girls' relationships (e.g., heightened friendship and social network stress; for reviews, see Cyranowski et al., 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2001; Rudolph, in press) also likely overwhelm the resources of depressed girls and interfere with their ability to solve even more minor problems. Failure to resolve problems may then create more severe stress. The present research documented that depressed girls do indeed generate more stress in their relationships; future research will need to investigate which specific interpersonal processes foster this interpersonal stress generation in depressed girls.

This self-generated interpersonal stress, in turn, heightened subsequent risk for depression in girls but not in boys. Because girls place a higher value than boys on forming and maintaining close relationships, and worry more than boys about negative evaluation or abandonment, threats to their relationships likely challenge girls' sense of self and relatedness with the world more than boys (Gore et al., 1993; for reviews, see Rose & Rudolph, 2006; Rudolph, in press). Moreover, because girls rely on their relationship partners for emotional support (for a review, see Rose & Rudolph, 2006), they may be at heightened risk for depression when they lack this support. Thus, girls are more likely than boys to show negative emotional responses to disruptions in their relationships.

The Role of Self-Generated Noninterpersonal Stress

As expected, self-generated noninterpersonal stress did not contribute to the continuity of depression over time. Interestingly, depression did predict the generation of noninterpersonal stress (in girls but not in boys) yet noninterpersonal stress did not perpetuate the cycle of depression. Many studies of the stress-generation process either collapse across domains of dependent stress (e.g., Cui & Vaillant, 1997; Daley et al., 1995; Hankin et al., 2007; Harkness, Monroe, Simons, & Thase, 1999) or specifically investigate the generation of interpersonal stress (e.g., Allen et al., 2006; Davila et al., 1995; Potthoff et al., 1995), making it difficult to place these findings in the context of prior research. Studies that do differentiate interpersonal versus noninterpersonal stress yield inconsistent findings regarding the role of noninterpersonal stress as an antecedent or consequence of depression. Using concurrent data, one study found a marginal association between independent but not self-generated noninterpersonal episodic stress and depression in boys but not in girls; this finding stood in contrast to stronger and more consistent links between interpersonal stress and depression (Rudolph et al., 2000). Another study found significant concurrent links between noninterpersonal stress (a composite that did not distinguish independent from self-generated stress) and depression, which was not moderated by sex (Shih et al., 2006). Providing opposing results, one study found that noninterpersonal (i.e., school) stress was concurrently associated with depressive symptoms in boys but not in girls (Sund, Larsson, & Wichstrom, 2003), whereas another study suggested that fluctuations in achievement stressors were associated more strongly with concurrent fluctuations in depressive symptoms in girls than in boys (Hankin et al., 2007).

Several methodological disparities may explain these inconsistencies, including differing indexes of stress (e.g., independent versus self-generated stress, type of noninterpersonal stress), measures and informants (e.g., self-report life stress and depression checklists vs. multi-informant interviews), and research designs (e.g., concurrent vs. longitudinal). Differences among prior studies also may be accounted for, in part, by whether co-occurring symptoms were considered. In this study, we conducted supplemental analyses to determine whether depressed girls' generation of noninterpersonal stress was accounted for by co-occurring externalizing symptoms. These analyses revealed that externalizing symptoms accounted for about one-quarter of the effect, but depression continued to significantly predict noninterpersonal stress generation.

Despite the fact that depression predicted noninterpersonal stress generation in girls, this stress did not predict subsequent depression. Thus, in contrast to the self-perpetuating cycle that emerged in the context of interpersonal stress, the noninterpersonal difficulties created by depressed girls did not increase their risk for future depression. Girls tend to place greater value on connection-oriented goals (e.g., developing intimacy, resolving problems) than on self-enhancement goals (e.g., achieving status; for reviews, see Cross & Madson, 1997; Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Given this emphasis, threats to girls' relationships are more likely to foster negative emotional responses than threats within noninterpersonal (e.g., achievement) domains. However, given inconsistencies across studies regarding the role of noninterpersonal stress exposure and generation in depression, more longitudinal research is needed to clarify these processes and the associated sex differences.

Limitations

A few caveats should be considered when interpreting results from this study. Although the use of diagnostic interviews to assess depression represented a methodological strength, our sample size led us to use a continuous index of depression severity rather than a categorical diagnosis. Relatedly, our sample included a reasonable percentage of youth with symptoms and diagnoses of depression, but it was not a severely depressed sample. Given evidence that youth depression is best viewed as a dimensional continuum rather than a discrete category (Hankin et al., 2005), along with evidence that the links between stress and depression are similar for clinical and subclinical levels of symptoms (Shih et al., 2006), it is likely that the depression-stress-depression cycle that emerged in the present study would replicate in a more severely depressed sample (and, in fact, may be even stronger). However, research is needed to confirm the generalizability of the findings.

In addition, although the life-stress interview provided a sophisticated methodological assessment of stress, our reliance on parent and youth retrospective recall of events over one-year intervals may have introduced some memory biases. The interview circumvents these biases to the extent possible by including standard prompts for specific life events as well as by including follow-up questions that elicit very specific, objective information. Any information regarding the subjective distress of the youth and their diagnostic status is omitted during the coding of the events. Moreover, eliciting information from both youth and parents diminishes the problems associated with a mono-informant bias. However, no method of assessing life stress can entirely eradicate reporting biases. Ultimately, gathering converging evidence across different assessment methods is likely the best approach for characterizing the experience of life stress in depressed individuals.

Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

Within the context of these limitations, this research contributes to interpersonal and stress-generation perspectives (Coyne, 1976; Hammen, 2006), as well as to broad developmental psychopathology models of depression (Cicchetti et al., 1994; Hammen, 1992), which emphasize how the transactional exchanges between youth and their environments contribute to the onset and persistence of depression across development: Depressed youth, specifically girls, create stress in their relationships, which perpetuates their depression over time. In this way, interpersonal stress serves as both a consequence of prior disorder and an etiological influence on future disorder. Importantly, this self-perpetuating cycle may help to explain the growing sex difference in depression across development.

Although this study supported a reciprocal cycle of interpersonal stress and depression, it did not identify the specific processes through which stress generation occurs. According to the stress-generation perspective, both depressive symptoms and stable characteristics and behaviors of depression-prone individuals precipitate the generation of stress (Hammen, 2006). Research has identified a number of such characteristics and behaviors (for a review, see Hammen, 2006), but most of these studies examined stress generation either across gender, or within a female sample only. In one study of college students, negative cognitive style predicted interpersonal and dependent stress in females but not males (Safford, Alloy, Abramson, & Crossfield, 2007). Beyond this study, however, it is not clear whether particular types of depressive symptoms, disorder-induced impairment, or stable underlying traits predict the generation of stress in girls as compared to boys. Future research needs to clarify the processes that underlie the specific female-linked interpersonal cycle observed in the present study.

It is also important to note that self-generated interpersonal stress only partially accounted for the continuity of depression. Not surprisingly, there are likely to be many contributing factors (for reviews, see Harrington & Dubicka, 2001; Lara & Klein, 1999). This continuity may reflect a stable vulnerability (e.g., a genetic liability or a cognitive bias) that is carried across development, making individuals susceptible to depression at different life stages. Alternatively, continuity may stem from the physiological sequelae of a depressive episode. Stress-sensitization theory (Post, Rubinow, & Ballenger, 1984) posits that experiencing an episode of depression sensitizes the biological stress-response system, thereby lowering individuals' threshold of reactivity to life stress. Depression also may leave a psychological “scar” (Rohde, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1990) that increases the likelihood of recurrent or chronic symptoms. For example, depressed youth develop a negative view of themselves and others over time (Cole, Martin, Peeke, Seroczynski, & Fier, 1999; Pomerantz & Rudolph, 2003); if these negative cognitions persist beyond an acute episode, they may serve as a vulnerability to future depression. Finally, depression continuity may be due, in part, to continuity in youths' environment (e.g., exposure to poverty or parental conflict). Of course, the generation of stress within relationships may reflect the interpersonal expression of a genetic or psychological liability or a problematic environment, thus uniting these diverse perspectives. For instance, research indicates a genetic influence on exposure to stressful environments (Kendler & Karkowski-Shuman, 1997), perhaps driven by the generation of stress. Continued integration of these perspectives will contribute to comprehensive theories about the development and perpetuation of youth depression.

Given the well-established phenomenon that past depression is the best predictor of future depression (e.g., Lewinsohn et al., 1989; Tram & Cole, 2006), understanding the mechanisms that underlie this continuity is key to developing effective prevention and intervention efforts. These findings suggest that one way to interrupt this cycle of depression and impairment is to lessen the adverse influence of girls' symptoms on their relationships. At an individual level, teaching adaptive ways to cope with depressive symptoms and associated stressors would diminish the withdrawal, conflict, and disruption as well as the resulting feelings of demoralization that girls may experience in the context of depression. Moreover, educational efforts to teach families and peer groups how to cope with depression in their relationship partners may counteract negative reactions to depressive symptoms and behaviors.

Footnotes

Because some research suggests that comorbid depression and externalizing disorders are associated with heightened stress generation (Rudolph et al., 2000), we conducted a path analysis identical to our original analysis, but also included W1 externalizing symptoms as a predictor of interpersonal stress generation. Path analysis revealed that externalizing symptoms did not account for interpersonal stress generation in depressed girls; in fact, externalizing symptoms did not significantly predict the generation of interpersonal stress.

We further examined whether externalizing symptoms accounted for noninterpersonal stress generation using the same approach as described for interpersonal stress. Path analysis revealed that externalizing symptoms accounted for a portion (23%) of the effect, but depression continued to serve as a significant predictor of noninterpersonal stress generation in girls.

References

- Allen JP, Insabella G, Porter MR, Smith FD, Land D, Phillips N. A social-interactional model of the development of depressive symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:55–65. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison BN, Schultz JB. Parent-adolescent conflict in early adolescence. Adolescence. 2004;39:101–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Text Revision. 4th. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS 4.0 User's Guide. Chicago: Small Waters Corp; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS 7.0 [Computer Software] Chicago: Small Waters Corp; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Overall fit in covariance structure models: Two types of sample size effects. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:256–259. [Google Scholar]

- Brengden M, Wanner B, Morin AJS, Vitaro F. Relations with parents and peers, temperament, and trajectories of depressed mood during early adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:579–594. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-6739-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris TO. Social origins of depression: A study of psychiatric disorder in women. New York, NY: Free Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. New York, NY: Sage Publications; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, Toth SL. A developmental psychopathology perspective on depression in children and adolescents. In: Reynolds WM, Johnston HF, editors. Handbook of depression in children and adolescents Issues in clinical child psychology. New York, NY: Plenum; 1994. pp. 123–141. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Martin JM, Peeke LA, Seroczynski AD, Fier J. Children's over- and underestimation of academic competence: A longitudinal study of gender differences, depression, and anxiety. Child Development. 1999;70:459–473. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus J, Paul G. Stress exposure and stress generation in child and adolescent depression: A latent trait-state-error approach to longitudinal analyses. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:40–51. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Depression and the response of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1976;85:186–193. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross SE, Madson L. Models of the self: Self-construals and gender. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;122:5–37. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.122.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X, Vaillant GE. Does depression generate negative life events? Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1997;185:145–150. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199703000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyranowski JM, Frank E, Young E, Shear K. Adolescent onset of the gender difference in lifetime rates of major depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:21–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley SE, Hammen C, Burge D, Davila J, Paley B, Lindberg N, et al. Predictors of the generation of episodic stress: A longitudinal study of late adolescent women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:251–259. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Windle M. Gender-specific pathways between maternal depressive symptoms, family discord, and adolescent adjustment. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:657–668. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Bradbury TN, Cohan CL, Tochluk S. Marital functioning and depressive symptoms: Evidence for a stress generation model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:849–861. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.4.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila J, Hammen C, Burge D, Paley B, Daley SE. Poor interpersonal problem solving as a mechanism of stress generation in depression among adolescent women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:592–600. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.4.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhart NK, Hammen C. Interpersonal predictors of onset of depression during the transition to adulthood. Personal Relationships. 2006;13:195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM, Beautrais AL. Subthreshold depression in adolescence and mental health outcomes in adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:66–72. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Keiley MK, Martin NC. Developmental trajectories of adolescents' depressive symptoms: Predictors of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:79–95. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH. Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:404–417. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Lorenz FO, Conger RD, Elder GG, Simons RL. Trajectories of stressful life events and depressive symptoms during adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:467–483. [Google Scholar]

- Goodyer IM, Altham PME. Lifetime exit events and recent social and family adversities in anxious and depressed school-age children and adolescents: I. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1991;21:219–228. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(91)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore S, Aseltine RH, Colten ME. Gender, social-relational involvement, and depression. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1993;3:101–125. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:555–561. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Cognitive, life stress, and interpersonal approaches to a developmental psychopathology model of depression. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:191–208. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Stress generation in depression: Reflections on origins, research, and future directions. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62:1065–1082. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Shih J, Altman T, Brennan PA. Interpersonal impairment and the prediction of depressive symptoms in adolescent children of depressed and nondepressed mothers. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42:571–577. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046829.95464.E5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Shih JH, Brennan PA. Intergenerational transmission of depression: Test of an interpersonal stress model in a community sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:511–522. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:773–796. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Fraley RC, Lahey BB, Waldman ID. Is depression best viewed as a continuum or discrete category? A taxometric analysis of childhood and adolescent depression in a population-based sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:96–110. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Mermelstein R, Roesch L. Sex differences in adolescent depression: Stress exposure and reactivity models in interpersonal and achievement contextual domains. Child Development. 2007;78:279–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness KL, Monroe SM, Simons AD, Thase M. The generation of life events in recurrent and non-recurrent depression. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:135–144. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington R, Dubicka B. Natural history of mood disorders in children and adolescents. In: Goodyer IM, editor. The depressed child and adolescent (2nd ed). Cambridge child and adolescent psychiatry. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2001. pp. 353–381. [Google Scholar]

- Hill JP. Adapting to menarche: Familial control and conflict. In: Gunnar MR, Collins WA, editors. Development during the transition to adolescence: Minnesota symposia on child psychology. Vol. 21. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. pp. 43–77. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Coyne JC, Blalock J. On the interpersonal nature of depression: Overview and synthesis. In: Joiner TE, Coyne JC, editors. The interactional nature of depression. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Karkowski-Shuman L. Stressful life events and genetic liability to major depression: Genetic control of exposure to the environment? Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:539–547. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797004716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Bolger N. Data analysis in social psychology. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. Handbook of Social Psychology. 4th. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 233–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kiesner J. Depressive symptoms in early adolescence: Their relations with classroom problem behavior and peer status. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2002;12:463–478. [Google Scholar]

- Kistner J. Children's peer acceptance, perceived acceptance, and risk for depression. In: Joiner TE, Brown JS, Kistner J, editors. The interpersonal, cognitive, and social nature of depression. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kistner JA, David-Ferdon CF, Repper KK, Joiner TE. Bias and accuracy of children's perceptions of peer acceptance: Prospective associations with depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:349–361. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Ouimette PC, Kelly HF, Ferro T, Riso LP. Test-retest reliability of team consensus best-estimate diagnoses of Axis I and II disorders in a family study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1043–1047. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. In: Kenny DA, editor. Methodology in the social sciences. Series. New York, NY: Guilford; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Rating scales to assess depression in school-aged children. Acta Paedopsychiatry. 1981;46:305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara ME, Klein DN. Psychosocial processes underlying the maintenance and persistence of depression: Implications for understanding chronic depression. Clinical Psychology Review. 1999;19:553–570. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B. Conflict between mothers and adolescents in single-mother, blended, and two-biological-parent families. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2005;5:47–70. doi: 10.1207/s15327922par0504_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Klein DN, Gotlib IH. Psychosocial functioning of young adults who have experienced and recovered from major depressive disorder during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:353–363. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Zeiss AM, Duncan EM. Probability of relapse after recovery from an episode of depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1989;98:107–166. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.98.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little SA, Garber J. Aggression, depression, and stressful life events predicting peer rejection in children. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:845–856. [Google Scholar]

- Little SA, Garber J. The role of social stressors and interpersonal orientation in explaining the longitudinal relation between externalizing and depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:432–443. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.3.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Lewinsohn PM. Life events and depression in adolescence: Relationship loss as a prospective risk factor for first onset of major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:606–614. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.4.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needham BL. Reciprocal relationships between symptoms of depression and parental support during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence in press. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan SA, Flynn C, Garber J. Prospective relations between rejection and depression in young adolescents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:745–755. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10:173–176. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Victimization by peers: Antecedents and long-term outcomes. In: Rubin KH, Asendorpf JB, editors. Social withdrawal, inhibition, and shyness in childhood. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1993. pp. 315–341. [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Epidemiologic Version-5. Nova Southeastern University; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Pomerantz EM, Rudolph KD. What ensues from emotional distress? Implications for competence estimation. Child Development. 2003;74:329–345. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RM, Rubinow DR, Ballenger JC. Conditioning, sensitization, and kindling: Implications for the course of affective illness. In: Post RM, Ballenger JC, editors. Neurobiology of mood disorders. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1984. pp. 432–466. [Google Scholar]

- Potthoff JG, Holahan CJ, Joiner TE. Reassurance seeking, stress generation, and depressive symptoms: An integrative model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:664–670. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.4.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Aikins JW. Cognitive moderators of the longitudinal association between peer rejection and adolescent depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32:147–158. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000019767.55592.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Borelli JL, Cheah CSL, Simon VA, Aikins JW. Adolescent girls' interpersonal vulnerability to depressive symptoms: A longitudinal examination of reassurance-seeking and peer relationships. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:676–688. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Are people changed by the experience of having an episode of depression? A further test of the scar hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1990;99:264–271. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo CJ, Daley SE, Gunderson BH. Interpersonal sensitivity, romantic stress, and the prediction of depression: A study of inner-city, minority adolescent girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:469–478. [Google Scholar]

- Rose A, Rudolph KD. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD. Gender differences in emotional responses to interpersonal stress during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30:3–13. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00383-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD. The interpersonal context of adolescent depression. In: Nolen-Hoeksema S, Hilt L, editors. Handbook of depression in adolescence. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Flynn M. Childhood adversity and youth depression: Influence of gender and pubertal status. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:497–521. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Flynn M, Abaied JL. A developmental perspective on interpersonal theories of youth depression. In: Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, editors. Child and adolescent depression: Causes, treatment, and prevention. New York, NY: Guilford; 2007. pp. 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C. Age and gender as determinants of stress exposure, generation, and reactions in youngsters: A transactional perspective. Child Development. 1999;70:660–677. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C, Burge D, Lindberg N, Herzberg DS, Daley SE. Toward an interpersonal life-stress model of depression: The developmental context of stress generation. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:215–234. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400002066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C, Daley SE. Mood disorders. In: Wolfe DA, Mash EJ, editors. Behavioral and emotional disorders in adolescents: Nature, assessment, and treatment. New York, NY: Guilford; 2006. pp. 300–342. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Ladd G, Dinella L. Gender differences in the interpersonal consequences of early-onset depressive symptoms. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2007;53:461–488. [Google Scholar]

- Safford SM, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Crossfield AG. Negative cognitive style as a predictor of negative life events in depression-prone individuals: A test of the stress generation hypothesis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;99:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, MacKenzie MJ. Research strategies for capturing transactional models of development: The limits of the possible. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:613–640. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber L, Hops H, Alpert A, Davis B, Andrews JA. Family support and conflict: Prospective relations to adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25:333–344. doi: 10.1023/a:1025768504415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih JH, Eberhart NK, Hammen C, Brennan PA. Differential exposure and reactivity to interpersonal stress predict sex differences in adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:103–115. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Adolescents' and parents' reasoning about actual family conflict. Child Development. 1989;60:1052–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb03536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In: Leinhart S, editor. Sociological methodology 1982. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Some new results on indirect effects and their standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In: Tuma N, editor. Sociological Methodology 1986. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association; 1986. pp. 159–186. [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH. Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1990;25:173–180. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Ragan J, Randall P. Prospective relations between social support and depression: Differential direction of effects for parent and peer support? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:155–159. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sund AM, Larsson B, Wichstrom L. Psychosocial correlates of depressive symptoms among 12-14-year-old Norwegian adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:588–597. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tram JM, Cole DA. A multimethod examination of the stability of depressive symptoms in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:674–686. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]