Abstract

The effect of perfectionism on acute treatment outcomes was explored in a randomized controlled trial of 439 clinically depressed adolescents (12–17 years of age) enrolled in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) who received cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), fluoxetine, a combination of CBT and FLX, or pill placebo. Measures included the Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised, the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire–Grades 7–9, and the perfectionism subscale from the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (DAS). Predictor results indicate that adolescents with higher versus lower DAS perfectionism scores at baseline, regardless of treatment, continued to demonstrate elevated depression scores across the acute treatment period. In the case of suicidality, DAS perfectionism impeded improvement. Treatment outcomes were partially mediated by the change in DAS perfectionism across the 12-week period.

Cognitive factors have been associated with the development of depression in both adults and adolescents and serve as a focus of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT; for a review see Clark & Beck, 1999). In adolescents, cognitions such as dysfunctional attitudes, hopelessness, and critical self-referent attributions have been linked to vulnerability to depression (e.g., Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989). One dysfunctional attitude, perfectionism, has been linked to a vulnerability to and the maintenance of depression. Weissman and Beck’s (1978) Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS) purports to measure self-defeating attitudes theorized to underlie clinical depression and anxiety. The DAS, as such, assesses a unitary perfectionism construct that could also be described as high personal standards or maladaptive evaluation concerns. Factor analytic work of the DAS scale with adults has consistently yielded subscales that have been labeled perfectionism (e.g., Imber et al., 1990), performance evaluation (Cane, Olinger, Gotlib, & Kuiper, 1986), and externalized self-esteem (Oliver & Baumgart, 1985).

In this article, we use the term DAS perfectionism when referring to the perfectionism subscale of the DAS, for clarity and parsimony. When referring to perfectionism as a more general construct, we use the term perfectionism. Although other measures of perfectionism exist (e.g., Hewitt & Flett, 1991b) and assess multidimensional components of perfectionism, this study evaluated DAS perfectionism in line with Beck’s model (Brown & Beck, 2002). Brown and Beck pointed out that “it thus can be argued that the DAS is, to a substantial degree, a measure of perfectionism, if perfectionism is construed in broad terms” (p. 236). Use of the DAS Perfectionism subscale allows for comparisons with relevant findings from two large studies, namely, the Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program (TDCRP; Blatt, Quinlan, Pilkonis, & Shea, 1995) and the Oregon Adolescent Depression Project (Lewinsohn, Hops, Roberts, Seeley, & Andrews, 1993). Recent work has also further explicated relations between various constructs of perfectionism and depression (see Powers, Zuroff, & Topciu, 2004).

Perfectionism appears to predispose to, precipitate, and prolong depression among university students, adult community samples, and adult psychiatric patients (Chang, 2000; Hewitt & Flett, 1991a; Rice, Ashby, & Slaney, 1998). A small number of studies have focused on relations between perfectionism and depression among children and adolescents (e.g., Einstein, Lovibond, & Gaston, 2000). Of interest, perfectionism and hopelessness are highly correlated in adolescents (Donaldson, Spirito, & Farnett, 2000). Grzegorek, Slaney, Franze, and Rice (2004) observed that perfectionism is related to self-critical depression but not dependent depression. In this case, self-critical depression refers to an introjective focus on self-worth, failure, worthlessness, and guilt, whereas dependent depression refers to depression associated with loneliness, helplessness, and fear of abandonment. Cole (1991) hypothesized that children develop self-perceptions based on feedback from others regarding their competence. In line with Cole’s reasoning, a child’s perception of failing to meet perfectionistic expectations affects the child’s self-perceptions, resulting in depression. Taken together, these findings indicate that perfectionism is associated with depression and other psychiatric symptoms in adults, whereas such relations are less clear among children and adolescents.

Higher levels of perfectionism may also potentiate forms of suicidality and hopelessness among adult psychiatric inpatients, outpatients, and college samples (Dean, Range, & Goggin, 1996; Hewitt, Flett, & Weber, 1994). Several studies have also examined relations between various forms of suicidality and perfectionism in adolescent psychiatric samples. Perfectionism among adolescents has been found, for example, to be linked with both suicide threat and intent (Hewitt, Flett, & Turnbull-Donovan, 1992; Hewitt, Newton, Flett, & Callander, 1997). In Boergers, Spirito, and Donaldson’s (1998) study of depressed adolescents, perfectionism discriminated between adolescent suicide attempters with a high intent to die and those with no intent to die. These findings suggest perfectionism may be associated with suicidality among adolescents.

Another important issue is understanding perfectionism’s relationship to treatment response. It is possible that CBT may be a more or less effective treatment than noncognitive therapies for individuals with depression and high levels of perfectionism. CBT, which is based on Beck’s cognitive model (e.g., Clark & Beck, 1999), attempts to rectify dysfunctional attitudes and beliefs associated with depression. The CBT protocol used in the Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) addressed cognitive factors believed to maintain depression, including perfectionism, within (a) CBT case formulation, (b) treatment expectations and goals, (c) cognitive distortions and realistic counter-thoughts, (d) maintenance, and (e) relapse prevention (as detailed in the TADS CBT manual available at https://trialweb.dcri.duke.edu/tads/tad/manuals/TADS_CBT.pdf).

Level of perfectionism prior to treatment may predict treatment outcome. Results from the National Institute of Mental Health TDCRP data indicate that therapeutic outcome in adults was significantly related to pretreatment level of DAS perfectionism (Blatt et al., 1995). Higher levels of DAS perfectionism predicted poor treatment outcome as indicated by severity of depression, general clinical functioning, and social adjustment in all four treatment conditions (Interpersonal Therapy, CBT, imipramine plus clinical management, and placebo control plus clinical management). As such, individuals with high levels of perfectionism may have unrealistic coping goals and standards that may undermine the recovery process or the maintenance of gains (Hewitt & Flett, 1996). Alternatively, perfectionism may function to decrease social support and increase interpersonal difficulties (e.g., Shahar, Blatt, & Zuroff, 2007; Zuroff & Blatt, 2002). In sum, evidence suggests that pretreatment perfectionism may predict treatment outcome among adults.

Alternatively, level of perfectionism prior to treatment may moderate treatment outcome. Moderator effects are prescriptive in that they explicate which individuals are more likely to benefit from a particular treatment versus another (Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002). As Kraemer and colleagues noted, “conceptually, moderators identify on whom and under what circumstances treatments have different effects” (p. 877). As such, a moderator variable interacts with treatment group, whereas a predictor variable does not. It remains unknown if pretreatment level of DAS perfectionism moderates treatment response for depression.

No studies to date in the adolescent literature have examined whether level of perfectionism during treatment for depression mediates outcome. Mediators are postrandomization factors that may represent mechanisms of treatment response. Ingram and colleagues (2006) highlighted the importance of exploring mediation: “The idea that cognition serves as the central mediating process is not new, and goes back at least to Beck’s (1967) speculation on the nature of depression” (p. 85). In light of the critical nature of mediation to cognitive models of depression, we evaluated this process in a large sample of depressed adolescents. However, given findings in the adult literature that medication can lead to significant cognitive change (e.g., Simons, Garfield, & Murphy, 1984), we further hypothesized that perfectionism would mediate treatment response within all treatment modalities. The identification of a mediator leads naturally to hypotheses about causal processes, which can be tested in studies specifically designed for these purposes. Randomized controlled trials are designed to test the efficacy of treatments and offer fruitful ground for the testing of moderators and mediators. However, moderators and mediators must be tested a priori within experimental studies to yield conclusive results. Within the context of randomized controlled trials, mediator analyses must be considered hypothesis-generating rather than hypothesis-testing (Kraemer et al., 2002).

The aim of this study was to examine whether DAS perfectionism is associated with depression and suicidality and to determine the extent to which DAS perfectionism is associated with treatment response among adolescents with major depression. We hypothesized that (a) DAS perfectionism would be significantly and positively associated with depression and suicidality severity prior to treatment, (b) pretreatment DAS perfectionism would either predict (main effect) or moderate (interaction with treatment) depression and suicidality outcomes after 12 weeks of acute treatment for depression, and (c) changes in DAS perfectionism during the intervention period would mediate treatment response. If perfectionism is found to moderate treatment outcome, we will have identified a pretreatment variable that could be used to decide what treatment may be the most helpful in the case of depressogenic cognition, such as perfectionism. If perfectionism is found to mediate treatment outcome, we would recommend experimental tests to explore the possibility that perfectionism represents a mechanism whereby treatment affects depression.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were 439 clinically depressed adolescents enrolled in the TADS. Sponsored by National Institute of Mental Health, TADS is a randomized controlled trial comparing the effects of CBT (n = 111), fluoxetine (FLX; n = 109), their combination (COMB; n = 107), and a pill placebo (PBO; n = 112). Randomized treatment was administered over a 12-week acute treatment period.

Adolescents in the TADS sample were between 12 and 17 years of age (inclusive) with a current primary Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnosis of major depressive disorder. Fifty-four percent of the participants were girls, 74% were Caucasian, and the mean age was 14.6 (SD = 1.5) years. A score of 45 or greater on the Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised (CDRS–R; Poznanski & Mokros, 1996) was required for study entry. The CDRS–R total scores at the pretreatment assessment ranged from 45 to 98 (M = 60, SD = 10.4), which is indicative of mild to severe depression. A mean total score of 60 corresponds with a normed T score of 75.5 (6.43), suggesting moderate to moderately severe depression.

Procedures

Details of consent and assent, Institutional Review Board approval, rationale, methods, design of the study, and other demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are detailed in previous reports (The TADS Team, 2003; 2005). Study assessments were conducted immediately prior to treatment (Baseline) and at two time points during the acute treatment period (Weeks 6 and Week 12). Clinical assessments were provided by an independent evaluator (IE) who was blind to the treatment assignment. Several self-report questionnaires completed by youth and parents were also collected.

Measures

CDRS–R(Poznanski & Mokros, 1996)

The CDRS–R is a 17-item clinician-rated depression severity measure that was completed by the IE. The CDRS–R total score serves as a primary outcome measure for the study. Scores on the CDRS–R are based on interviews with the adolescent and parent and can range from 17 to 113, with higher scores representing more severe depression. The scale has good internal consistency (coefficient α = .85), interrater reliability (r = .92), test–retest reliability (r = .78), and is correlated with a range of validity indicators including global ratings and diagnoses of depression (Pozanski & Mokros, 1996).

Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire–Grades 7–9

(SIQ-Jr; Reynolds, 1987). The SIQ-Jr is a 15-item adolescent self-report measure of suicidal thinking with a possible range of scores between 0 and 90. Severity of suicidal ideation was based on the total score, with higher scores indicating more severe suicidality. The SIQ-Jr has high internal consistency (coefficient α = .94) and moderate test–retest stability (r = .72; Reynolds, 1987).

Children’s Global Assessment Scale (Rey, Starling, Wever, Dossetor, & Plapp, 1995)

The Children’s Global Assessment Scale is a measure of general functioning during the past week, which was completed by the IE.

Perfectionism subscale of the DAS (Weissman & Beck, 1978)

The DAS is a self-report rating scale that assesses beliefs associated with vulnerability for depression. Although the DAS was originally developed within adult populations, it has been used widely within adolescent samples (e.g., Ackerson, Scogin, McKendree-Smith, & Lymen, 1998; Martin, Kazarian, & Breiter, 1995; Williams, Connolly, & Segal, 2001). Internal consistency is good and stability is excellent over 8 weeks among adults (Marton & Kutcher, 1993) as well as youth (Garber, Weiss, & Shanley, 1993). The scale consists of 40 statements on a 7-point Likert scale. Using data from the TDCRP, Imber and colleagues (1990) used a principal components analysis to examine the factor structure of the DAS. Two distinct factors emerged and were labeled perfectionism and need for approval. Fifteen items loaded substantially on the perfectionism factor. The items of this subscale are listed in Table 1. The item content of the DAS used in our study is identical to the DAS used with adults and adolescents in other studies.

TABLE 1.

Dysfunctional Attitude Scale Perfectionism Items

| Item # | Item |

|---|---|

| 1 | It is difficult to be happy unless one is good looking, intelligent, rich and creative. |

| 3 | People will probably think less of me if I make a mistake. |

| 4 | If I do not do well all the time, people will not respect me. |

| 8 | If a person asks for help, it is a sign of weakness. |

| 9 | If I do not do as well as other people, it means I am an inferior human being. |

| 10 | If I fail at my work, then I am a failure as a person. |

| 11 | If you cannot do something well, there is little point in doing it at all. |

| 13 | If someone disagrees with me, it probably indicates he does not like me. |

| 14 | If I fail partly, it is as bad as being a complete failure. |

| 15 | If other people know what you are really like, they will think less of you. |

| 20 | If I don’t set the highest standards for myself, I am likely to end up a second-rate person. |

| 21 | If I am to be a worthwhile person, I must be truly outstanding in at least one major respect. |

| 22 | People who have good ideas are more worthy than those who do not. |

| 23 | I should be upset if I make a mistake. |

| 26 | If I ask a question, it makes me look inferior. |

The perfectionism subscale was recently identified in a factor analysis of the DAS within the TADS sample (Rogers et al., 2009). Confirmatory factor analysis revealed a two-factor model, with scales corresponding to perfectionism and need for social approval, which provided a satisfactory fit to the data. The goodness-of-fit was equivalent across sexes and age groups. The perfectionism scale demonstrated an excellent degree of internal consistency (α = .91). Possible scores on the perfectionism factor range from 15 to 105, with higher scores representing greater perfectionism.

Statistical Analyses

Primary outcomes were severity of depression and suicidality during the 12-week treatment period, as measured by IE-report CDRS–R total score and the adolescent-report SIQ-Jr total score, respectively. An intent-to-treat analysis approach was employed, and thus all 439 patients randomized to treatment were included in analyses regardless of study completion, protocol adherence, or treatment compliance. Given that these analyses were exploratory, nondirectional statistical tests were conducted and the level of significance was set at .05.

Sixteen youth were missing a DAS perfectionism score and 11 were missing a SIQ-Jr total score at baseline. For the baseline and intent-to-treat analyses, the baseline sample median score was imputed when a baseline score was missing. The sample median was 53 for DAS perfectionism and 16 for the SIQ-Jr total score. The mean baseline DAS perfectionism score was 53.7 (SD = 17.6, n = 423) without imputation and 53.7 (SD = 17.3) with imputation, while the mean baseline SIQ-Jr total score was 23.7 (SD = 21.8, n = 428) without imputation and 23.5 (SD = 21.6) with imputation. General Linear Models with a posteriori t tests were employed to compare the treatment arms on key baseline clinical characteristics. When the assumptions of this test were not met, a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used. Pearson product-moment coefficients were conducted to examine the correlation between measures at the three assessment points.

DAS perfectionism’s effect on treatment was examined using an approach recommended by Kraemer and colleagues (Kraemer et al., 2002). As described in the introduction, a nonspecific predictor is a pretreatment variable that has a significant effect on outcome regardless of treatment condition (i.e., main effect only—as evidenced by a perfectionism or perfectionism × time effect). A moderator, on the other hand, is considered a special type of predictor whereby (a) treatment effectiveness is significantly influenced by level of the pretreatment factor, and (b) a significant interaction between the pretreatment factor and treatment (with or without a main effect of the pretreatment factor) is demonstrated (i.e., perfectionism × treatment or perfectionism × treatment × time). A mediator is a postrandomization factor that may represent a mechanism or help explain treatment response. Using Kraemer et al.’s (2002) criteria, a mediator is a postrandomization variable that is correlated with treatment and demonstrates a significant main and / or interaction with treatment outcome.

The core random regression model (RRM) included both fixed (treatment, natural log of time, treatment × time, site) and random (patient, patient × time) effects. As previously reported (The TADS Team, 2004), the primary efficacy findings for the 12-week treatment period indicated that treatment was related to the CDRS–R and SIQ-Jr outcomes. Our first step in the current analysis was to replicate the published results using the core RRM without DAS perfectionism terms in the model. Then, baseline DAS perfectionism and its interaction terms (DAS perfectionism × time, DAS perfectionism × treatment, and DAS perfectionism × treatment × time) were added to the core model to test whether DAS perfectionism was a predictor versus a moderator of treatment effects.

DAS perfectionism change scores across the acute treatment period (baseline minus end of treatment difference scores) were used to determine whether a decrease in DAS perfectionism during the treatment period mediated outcome. DAS perfectionism change scores were available for 368 of the 439 (83.8%) enrolled patients (COMB = 83.2%, FLX = 89.0%, CBT = 78.4%, PBO = 84.0%) because of study exit or missing Week 12 assessments. The four treatment arms did not differ significantly, however, in the rate of missing change score data, χ2(N = 368, 3) = 4.7, p = .196. Change scores were employed rather than time-dependent DAS perfectionism scores to control for potential moderating effects of pretreatment scores (H. C. Kraemer, personal communication, October 5, 2006). As derived, a more positive change score represents a greater decrease in DAS perfectionism over the treatment period. Because of the large variability in the change scores, a Kruskal-Wallis test was conducted to determine whether treatment was related to change in DAS perfectionism.

Next, an RRM was conducted to (a) examine treatment differences in DAS perfectionism over time, and (b) derive predicted scores for each patient at baseline and Week 12, as well as change scores, based on the individual trajectories generated by the RRM. The derived predicted perfectionism scores are estimated scores adjusted for the fixed (treatment, natural log of time, treatment × time, site) and random (patient, patient × time) effects in the model. Predicted scores were generated for the purposes of imputation for the 71 youth missing a Week 12 assessment. The mean for the DAS perfectionism change score without imputation was 9.2 (SD = 17.2, n = 368) and with imputation was 9.0 (SD = 15.9, n = 439). The range was −46.0 to 83.0. If correlated with treatment, then the final step for assessing mediator status was to conduct the RRM with DAS perfectionism change and its interaction terms in the model. Paired contrasts were conducted only if a significant treatment or treatment × time effect was observed.

RESULTS

Baseline Analyses

Patients in the four randomized treatment conditions did not differ significantly at baseline with regard to CDRS–R depression severity, SIQ-Jr suicidality scores, DAS perfectionism, global functioning, age at time of consent, duration of the current depressive episode, or total number of concurrent psychiatric disorders (all tests, p > .05). Although differences in the SIQ-Jr total scores were not detected between the four treatment arms (Kruskal-Wallis, p = .572), the proportion of patients with a SIQ-Jr total score of 31 or greater, which is indicative of clinically significant suicidal risk, was significantly higher in the COMB (39.3%) arm relative to FLX (25.7%, p = .036), CBT (24.3%, p = .025), and PBO (25.0%, p = .033).

Correlational Analyses

At baseline, DAS perfectionism scores ranged from 15 to 99 and were significantly correlated with CDRS–R (r = .19, p < .001) and SIQ-Jr (r = .32, p < .001) total scores, with greater DAS perfectionism associated with more severe depression and suicidality. In addition, baseline depression and suicidality were moderately related (r = .33, p <.001). Baseline DAS perfectionism was also correlated with Week 12 DAS perfectionism scores (r = .57, p < .001, n = 368) and change in DAS perfectionism (r = .35, p < .001, n = 368), in that higher baseline depression scores were associated with greater reductions in DAS perfectionism score across the 12 weeks. Correlation coefficients were conducted to examine multicollinearity between DAS perfectionism and outcomes at the three assessment points. The results indicated modest cross-modal associations. For depression, the coefficient was 0.19 at baseline, 0.35 at Week 6, and 0.36 at Week 12, whereas the correlation with suicidality was 0.32 at baseline, 0.26 at Week 6, and 0.41 at Week 12 (all p < .05).

Primary Efficacy Analysis

Using a RRM with site as a fixed effect we replicated our previously reported findings with the CDRS–R and SIQ-Jr outcomes (The TADS Team, 2004). Across treatments, the percentage of participants with a score greater than or equal to 31 (representing significantly greater suicidal risk) ranged from 25 to 40% at baseline. At Week 12 the percentage ranged from 6 to 19%. Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations (SD) for the depression, suicidality, and DAS perfectionism measures at baseline, Week 6, and Week 12.

TABLE 2.

Depression, Suicidality, and Perfectionism: Means and Standard Deviations

| Total |

COMB |

FLX |

CBT |

PBO |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Assessment | N | M ± SD | N | M ± SD | N | M ± SD | N | M ± SD | N | M ± SD |

| Depression | CDRS–R total score | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 439 | 60.1 ± 10.4 | 107 | 60.8 ± 11.6 | 109 | 59.0 ± 10.2 | 111 | 59.6 ± 9.2 | 112 | 61.1 ± 10.5 | |

| Week 6 | 389 | 42.1 ± 12.3 | 98 | 38.5 ± 12.7 | 99 | 39.4 ± 11.5 | 97 | 45.3 ± 11.8 | 95 | 45.4 ± 11.6 | |

| Week 12 | 378 | 38.2 ± 13.4 | 95 | 33.4 ± 11.9 | 97 | 36.8 ± 12.7 | 90 | 41.4 ± 14.2 | 96 | 41.4 ± 13.4 | |

| Suicidality | SIQ-Jr total score | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 439 | 23.5 ± 21.6 | 107 | 27.2 ± 24.5 | 109 | 21.8 ± 19.1 | 111 | 21.8 ± 21.0 | 112 | 23.4 ± 21.3 | |

| Week 6 | 362 | 15.2 ± 17.6 | 86 | 14.2 ± 18.4 | 95 | 16.1 ± 18.5 | 89 | 12.8 ± 14.9 | 92 | 17.6 ± 18.3 | |

| Week 12 | 370 | 13.4 ± 16.5 | 90 | 12.5 ± 16.5 | 97 | 14.8 ± 17.3 | 91 | 11.9 ± 14.9 | 92 | 14.4 ± 17.3 | |

| Perfectionism | DAS subscale score | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 439 | 53.7 ± 17.3 | 107 | 54.1 ± 17.4 | 109 | 52.2 ± 16.3 | 111 | 52.3 ± 17.3 | 112 | 56.0 ± 18.0 | |

| Week 6 | 307 | 48.2 ± 17.5 | 71 | 44.2 ± 18.7 | 84 | 46.6 ± 17.3 | 76 | 51.3 ± 16.2 | 76 | 50.5 ± 17.3 | |

| Week 12 | 368 | 45.2 ± 19.6 | 89 | 40.0 ± 20.8 | 97 | 46.1 ± 19.4 | 87 | 47.5 ± 16.9 | 95 | 47.1 ± 20.3 | |

| Change score-unadjusted | 368 | 9.2 + 17.2 | 89 | 14.8 + 17.5 | 97 | 6.4 + 16.8 | 87 | 5.7 + 14.4 | 95 | 10.1 + 18.6 | |

| Change score-adjusted | 439 | 8.8 + 16.2 | 107 | 14.4 + 16.0 | 109 | 6.6 + 15.9 | 111 | 5.5 + 12.8 | 112 | 9.6 + 17.2 | |

Note. COMB = CBT and fluoxetine; FLX = fluoxetine; CBT = cognitive behavior therapy; PBO = pill placebo; CDRS–R = Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised total score; SIQ-Jr = The Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire Grades 7–9 total score; DAS = Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale Perfectionism subscale score.

Predictor and Moderator Analyses

For the depression outcome, significant time, F(1, 408) = 94.7, p < .001, and DAS perfectionism, F(1, 425) = 10.1, p < .002, effects were demonstrated. However, the DAS perfectionism × treatment, F(3, 413) = 1.5, p = .215, and DAS perfectionism × treatment × time, F(3, 405) = 0.7, p = .579, interaction terms were not statistically significant. In addition, the main effects of DAS perfectionism, F(1, 410) = 43.2, p <.001, and DAS perfectionism × time, F(1, 416) = 7.0, p <.009, were significant for the suicidality outcome, whereas the DAS perfectionism interactions with treatment were not. A main effect (perfectionism or perfectionism × time) in absence of an interaction with treatment (perfectionism × treatment or perfectionism × treatment × time) indicates that DAS perfectionism was a predictor of outcome but not a moderator of outcome. The predictor results indicate that adolescents with higher versus lower DAS perfectionism scores at baseline, regardless of treatment, continued to demonstrate elevated depression scores across the acute treatment period. In the case of suicidality, DAS perfectionism impeded improvement. Adolescents with DAS perfectionism scores at or above the 90th percentile (score ≥ 78) had higher CDRS–R and SIQ-Jr scores at baseline and Week 12.

Mediator Analyses

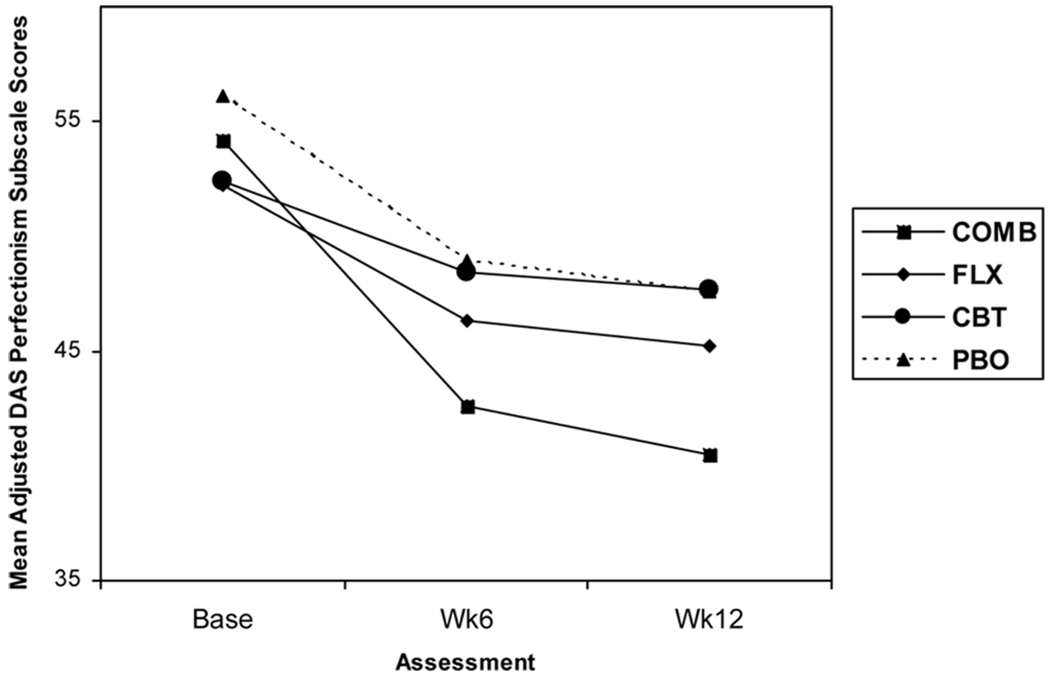

The primary analysis described earlier (and The TADS Team, 2004) indicated a significant relationship between treatment and treatment outcomes, as demonstrated by the significant treatment × time interaction. The RRM with DAS perfectionism as the outcome demonstrated significant time, F(1, 396) = 110.2, p < .001, and treatment × time interaction, F(3, 396) = 5.4, p < .002, effects. Participants in COMB treatment demonstrated a greater rate of improvement when compared to participants in the other three conditions (all p < .026), whereas participants in FLX, CBT, and PBO did not differ from one another. At the end of acute treatment, participants in COMB treatment had lower DAS perfectionism scores relative to those in CBT and PBO (p < .006). However, participants in COMB treatment did not differ from those in FLX (p = .065). Those in the FLX, CBT, and PBO groups did not differ significantly in terms of DAS perfectionism at Week 12. Figure 1 details the relation between treatment group and level of DAS perfectionism.

FIGURE 1.

Change in Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale Perfectionism subscale scores (DAS) over 12 weeks of treatment. Note: Base = baseline; COMB = CBT and fluoxetine; FLX = fluoxetine; CBT = cognitive behavior therapy; PBO = pill placebo; Wk = week.

Next, a Kruskal-Wallis test was used to determine if DAS perfectionism change scores were correlated with treatment. The effect of treatment on change scores was significant, χ2(n = 439, 3) = 22.5, p < .001, with participants in COMB treatment presenting with a greater decrease in DAS perfectionism relative to FLX (p < .001), CBT (p < .001), and PBO (p = .014) across the 12 weeks. The ordering of effects was COMB > PBO, PBO, FLX, and CBT. Although participants in FLX did not significantly differ from those in CBT (p = .510) or PBO (p = .202), participants in CBT did not experience as great a reduction in DAS perfectionism scores as those in PBO (p = .029). These results indicate that postrandomization change in DAS perfectionism was associated with treatment.

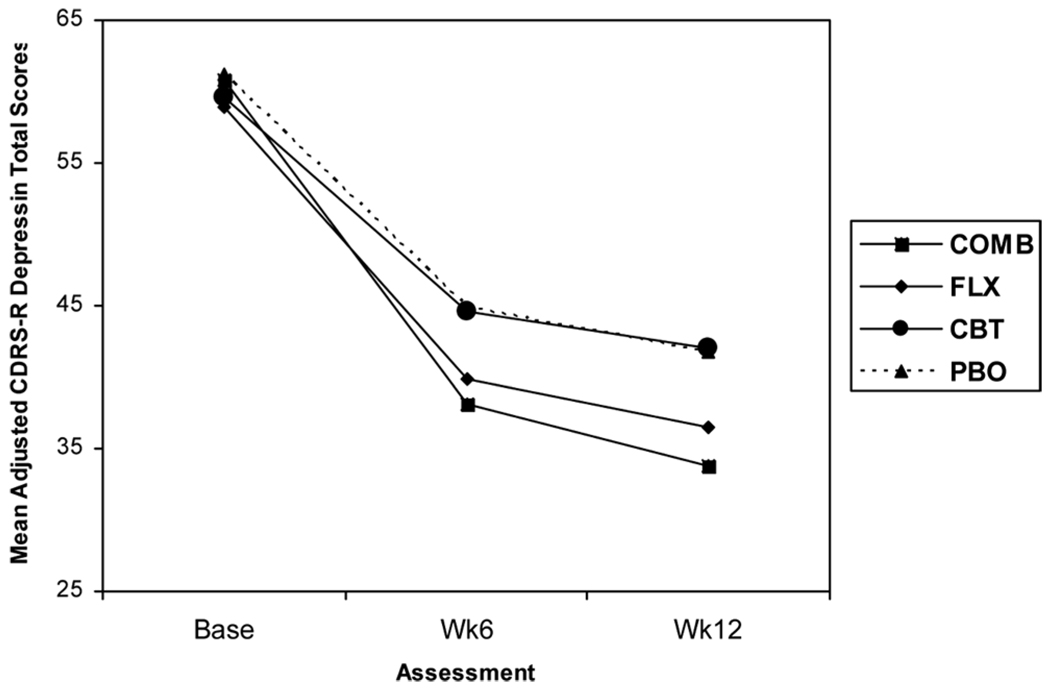

Next, we conducted the core RRM with DAS perfectionism change and its interactions included to determine if the main effect of DAS perfectionism and / or its interaction with treatment were significant. Significant time, F(1, 401) = 687.4, p < .001; DAS perfectionism × time, F(1, 385) = 23.4, p < .001; and treatment × time, F(3, 402) = 3.6, p = .014, effects were demonstrated for the depression outcome. Participants in COMB treatment experienced a significantly greater rate of improvement in depression when compared to those in CBT (p = .007) and PBO (p = .024). With DAS perfectionism change terms in the model, the significant treatment × time effect was reduced from F(3, 411) = 9.1, p < .001, to F(3, 402) = 3.6, p = .014. In addition, the slope difference between the COMB and FLX groups reported in the primary analysis was no longer observed (p = .067). Participants in FLX evidenced significantly greater depression change relative to those in CBT (p = .021), whereas participants in FLX and CBT did not differ from those in PBO. Week 12 comparisons were similar to the primary findings without DAS perfectionism change in the model (COMB = FLX > CBT = PBO).

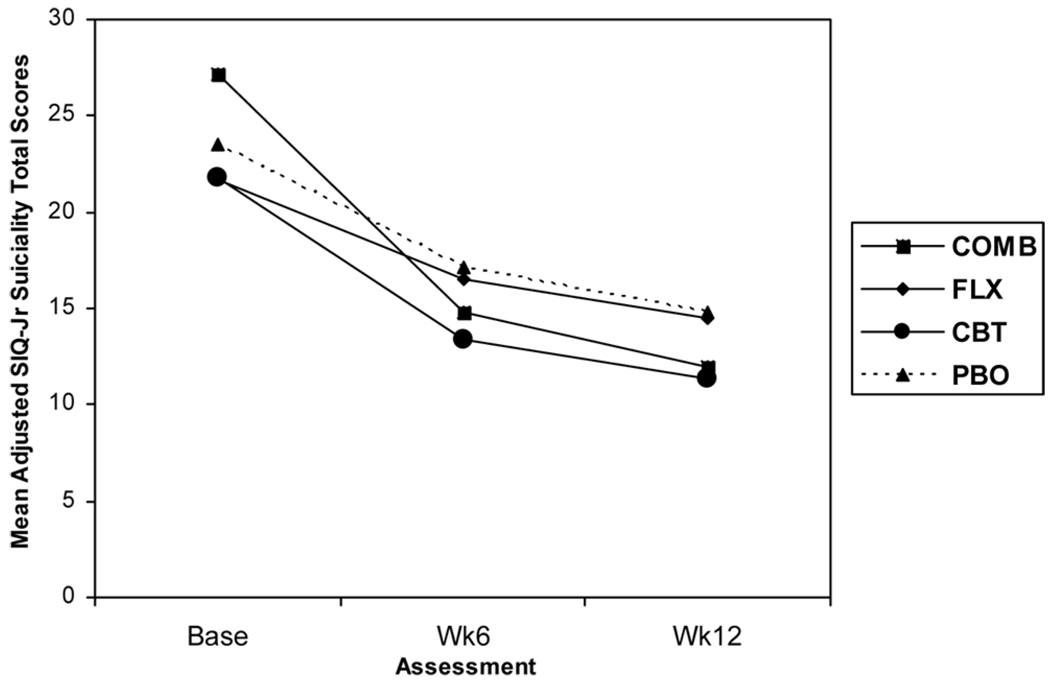

With regard to suicidality, significant time, F(1, 411) = 59.2, p < .001, and DAS perfectionism × time, F(1, 389) = 20.7, p < .001, effects were observed. The treatment × time, F(3, 402) = 3.6, p = .014, effect reported in the primary analysis was no longer statistically significant, F(3, 410) = 1.8, p = .141. The COMB treatment participants demonstrated a greater rate of improvement in suicidality when compared to youth receiving FLX (p = .023). No other significant differences were detected between the four arms in terms of slope or Week 12 outcomes. In the case of suicidality, change in DAS perfectionism significantly reduced the treatment × time interaction observed in the primary analysis.

Taken together, results indicate that change in DAS perfectionism during the acute treatment period was a partial mediator of the depression and suicidality outcomes, as revealed by the significant DAS perfectionism × time main effect. The main effects of DAS perfectionism change eliminated the treatment × time interaction for suicidality while diminishing this interaction in the case of depression. The effects of treatment across time after controlling for postrandomization perfectionism are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Effect sizes, using Cohen’s d (Cohen, 1988), for the depression score treatment comparisons are included in Table 3. The inclusion of DAS perfectionism change in the RRM resulted in reduced effect sizes for treatment comparisons.

FIGURE 2.

Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised (CDRS–R) total scores adjusted for Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale perfectionism change scores. Note: Base = baseline; COMB = CBT and fluoxetine; FLX = fluoxetine; CBT = cognitive behavior therapy; PBO = pill placebo; Wk = week.

FIGURE 3.

The Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire Grades 7–9 total score (SIQ-Jr) adjusted for Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale perfectionism change scores. Note: Base = baseline; COMB = CBT and fluoxetine; FLX = fluoxetine; CBT = cognitive behavior therapy; PBO = pill placebo; Wk = week.

TABLE 3.

Effect Sizes (ES) for CDRS–R Depression Score Treatment Comparisons

| Comparison | ES Without Perfectionism Change |

ES With Perfectionism Change |

|---|---|---|

| Active vs. PBO | ||

| COMB vs. PBO | 0.98 | 0.96 |

| FLX vs. PBO | 0.68 | 0.64 |

| CBT vs. PBO | −0.03 | −0.02 |

| Active treatments | ||

| COMB vs. FLX | 0.31 | 0.33 |

| COMB vs. CBT | 0.95 | 0.92 |

| FLX vs. CBT | 0.66 | 0.62 |

Note. PBO = placebo; Base = baseline; COMB = CBT and fluoxetine; FLX = fluoxetine; CBT = cognitive behavior therapy.

DISCUSSION

The present study sought to examine relations amongst severity of DAS perfectionism, depression, and suicidality in a sample of clinically depressed adolescents. Our first hypothesis was that DAS perfectionism would be significantly and positively associated with depression and suicidality severity. This hypothesis was supported, as higher DAS perfectionism scores were correlated with more severe depression and suicidality at the baseline, Week 6, and Week 12 assessments.

Our second hypothesis was that pretreatment DAS perfectionism would either predict (main effect) or moderate (interaction with treatment) depression and suicidality outcomes after 12 weeks of acute treatment for depression. DAS perfectionism had predictive value given that depressed adolescents with higher levels of DAS perfectionism scores continued to demonstrate consistently elevated depression scores over the acute treatment period. In regard to the suicidality outcome, adolescents with higher levels of DAS perfectionism scores at baseline experienced less improvement over the acute treatment period, regardless of treatment type. All treatments resulted in decreases in DAS perfectionism, with the combination of CBT and medication resulting in the greatest decrease.

Care must be taken, however, in drawing broad conclusions from these results. Whereas perfectionism has been shown to be a relatively stable trait among adults (Cox & Enns, 2003), this may not be the case among adolescents. A recent study found that dysfunctional attitudes were not stable in early to middle adolescence but exhibited relative stability during middle to late adolescence (Hankin, 2005). As participants in the TADS study ranged from 12 to 17 years of age, it is possible that the stability of perfectionism may have varied with age. Further longitudinal studies, of both normal and clinical samples, may help establish the fluidity or stability of perfectionism over time, independent of changes associated with the treatment for depression.

Although highly perfectionistic adolescents did not benefit as much from treatment as their less perfectionistic counterparts, it is noteworthy that brief treatment, both pharmacological and psychological, was still effective in this population. Previous findings suggested that adults with strong perfectionistic tendencies may respond better to long-term, intensive, psychodynamic treatments than to short-term treatments (Blatt & Ford, 1994). Moreover, Blatt et al. (1995) proposed that in targeting perfectionism through treatment, therapists are attempting to change personality structure, a goal that necessitates a longer time frame than short-term therapy allows. Our finding that all treatment groups experienced a significant reduction in DAS perfectionism suggests that certain dysfunctional attitudes may not be as resistant to change as previously thought, at least among some youth.

Our third hypothesis regarding DAS perfectionismand treatment response was also supported as perfectionism mediated the effect of treatment on depression and suicidality, reducing and eliminating the treatment effect in each case respectively. Including DAS perfectionism in our statistical model resulted in modest changes in effect sizes for treatment comparisons. The moderate correlations between DAS perfectionism and treatment outcomes, coupled with the continued statistical significance of DAS perfectionism after controlling for the effects of treatment and time, suggest that mediation effects cannot be explained as a function of multicollinearity.

Our results suggest that DAS perfectionism is implicated as a mediator and possible mechanism in the treatment of depression among adolescents. As Kraemer and colleagues (2002) pointed out, “All mechanisms [of treatment] are mediators but not all mediators are mechanisms” (p. 878). The identification of mediators represents the first step in examining possible mechanisms of change. To be sure, demonstrating causality is more difficult than establishing mediator status. Additional research is necessary to demonstrate the mechanism of perfectionism. Our current analyses, therefore, must be considered exploratory. Recent reanalysis of the TDCRP data indicated dual change processes, wherein DAS perfectionism predicted subsequent change in depression and the strength of the therapeutic alliance predicted change in perfectionism (Hawley, Ho, Zuroff, & Blatt, 2006). Advancing our understanding of change processes, including that of mediation, will allow for the refinement of existing treatments as well as the development of new treatments.

Our finding that medication changed DAS perfectionism is congruent with research among adults suggesting that medication can change cognition (e.g., Simons et al., 1984). Cognitive models of depression posit that CBT works by changing cognition (e.g., Beck, 1967). Demonstrating this, however, has proven challenging (Clark & Beck, 1999). In a provocative recent study, latent depressive schemas, as measured by a scale of cognitive reactivity, were found to be associated with sensitivity to a reduction of 5-HT (Booij & Van der Does, 2007). It is possible, as such, that the cognitive and neurobiological substrates of depression are linked.

Confidence in our interpretation of the results obtained is constrained by several factors. First, other measures that tap multiple dimensions of perfectionism exist and associations between these measures of perfectionism and measures of mood may vary. Thus, although this study contributes to existing empirical work on perfectionistic dysfunctional attitudes, how this study speaks to the larger empirical and theoretical literature on the construct of perfectionism remains to be demonstrated. Indeed, researchers have distinguished between social prescribed perfectionism and other-oriented perfectionism (Hewitt & Flett, 1991b). Brown and Beck (2002) noted that the DAS perfectionism factor parallels Hewitt and Flett’s (1991b) construct of socially prescribed perfectionism, as both relate to the internalization of socially dictated norms. Thus, our findings regarding DAS perfectionism reflect the self-focused, depressogenic cognitive set described in Beck’s (1967) model. Replication of our results with other measures of perfectionism is warranted.

Site was retained in the model and treated as a fixed effect in our analysis because treatments were nested within each clinical site. To be consistent with the statistical analysis approach applied in the TADS primary analysis (The TADS Team, 2004), we included site as a covariate in the current analysis. In the primary and current secondary analysis, the site interaction terms were omitted from the final regression models due to a lack of statistical significance (p > .05).

In addition, methods for demonstrating mediation continue to develop. Such methods, in combination with research utilizing more temporally sensitive designs, may further explicate transactional relations between perfectionism and treatment outcomes. Our findings suggest that DAS perfectionism changes in tandem with depressive symptoms. As DAS perfectionism decreases, depression and level of suicidality appear to similarly decline. Microanalytic studies designed to assess change in cognition over the course of treatment for depression would advance knowledge in this domain. Similarly, although we could not assess the degree to which DAS perfectionism was addressed during CBT sessions, dose effects could be explored in such microanalytic work. Moreover, some have suggested that temporal precedence is essential in defining a mediator (e.g., Kazdin & Nock, 2003; Weersing & Weisz, 2002). We note that although establishing that a variable is a mediator indicates the existence of relations between the treatment and the mediator, these relations may or may not be causal. The definition of mediators proposed by Kraemer and her colleagues (2002) does not assume that the causal pathways are known nor is any necessary causal role assumed once identified. Often the identification of a mediator leads to hypotheses about the possible causal role to be tested in future studies specifically design for those purposes. Thus, temporal precedence is a theoretical rather than an analytic criterion for mediation. Although we recognize the importance of this theoretical criterion, we present our results in the hopes of generating further studies that can test these change processes in a more sensitive manner. Last, the inclusion of DAS perfectionism in our statistical model led to modest changes in effect sizes. However, given that change is likely multiply determined, modest mediator effects remain clinically relevant.

Within the context of these limitations, our findings offer support for the notion that DAS perfectionism is related to both adolescent depression and suicidality. Clinicians may find it helpful, as a consequence, to assess levels of dysfunctional attitudes, such as perfectionism, among depressed youth and to target such cognition in therapy. Although DAS perfectionism did not moderate treatment outcome, given the robust outcomes evidenced in the COMB treatment with respect to depression, suicidality, and DAS perfectionism—combination treatment may be the safest recommendation in light of current evidence.

Acknowledgments

The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) is supported by contract N01 MH80008 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) to Duke University Medical Center (John S. March, Principal Investigator). Preparation of this manuscript was supported by NIMH fellowship F31 MH075308 to Rachel H. Jacobs. Portions of this work were presented at the World Congress of Behavioural and Cognitive Therapies, 2007, the meeting of the Association for Behavior and Cognitive Therapies, 2006, and the American Psychological Association, 2006. TADS is coordinated by the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and the Duke Clinical Research Institute at Duke University Medical Center in collaboration with NIMH, Rockville, Maryland. The Coordinating Center principal collaborators are John March, Susan Silva, Stephen Petrycki, John Curry, Karen Wells, John Fairbank, Barbara Burns, Marisa Domino, and Steven McNulty. The NIMH principal collaborators are Benedetto Vitiello and Joanne Severe. Principal Investigators and Co-investigators from the clinical sites are as follows: Carolinas Medical Center: Charles Casat, Jeanette Kolker, Karyn Riedal, Marguerita Goldman; Case Western Reserve University: Norah Feeny, Robert Findling, Sheridan Stull, Felipe Amunategui; Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia: Elizabeth Weller, Michele Robins, Ronald Weller, Naushad Jessani; Columbia University: Bruce Waslick, Michael Sweeney, Rachel Kandel, Dena Schoenholz; Johns Hopkins University: John Walkup, Golda Ginsburg, Elizabeth Kastelic, Hyung Koo; University of Nebraska: Christopher Kratochvil, Diane May, Randy LaGrone, Martin Harrington; New York University: Anne Marie Albano, Glenn Hirsch, Tracey Knibbs, Emlyn Capili; University of Chicago/Northwestern University: Mark Reinecke, Bennett Leventhal, Catherine Nageotte, Gregory Rogers; Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center: Sanjeev Pathak, Jennifer Wells, Sarah Arszman, Arman Danielyan; University of Oregon: Anne Simons, Paul Rohde, James Grimm, Lananh Nguyen; University of Texas Southwestern: Graham Emslie, Beth Kennard, Carroll Hughes, Maryse Ruberu; Wayne State University: David Rosenberg, Nili Benazon, Michael Butkus, Marla Bartoi. Greg Clarke (Kaiser Permanente) and David Brent (University of Pittsburgh) are consultants; James Rochon (Duke University Medical Center) is statistical consultant.

Footnotes

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

Publisher's Disclaimer: The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Disclosure: Susan Silva is a consultant with Pfizer. Christopher Kratochvil receives research support from McNeil, Abbott, Shire, Eli Lilly, and Cephalon, and is a consultant for Abbott, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Cephalon, AstraZeneca, Organon, and Shire, and is on the Speaker’s Bureau of Eli Lilly. Golda Ginsburg received research support from Pfizer. John March is a consultant or scientific advisor to Pfizer, Lilly, Wyeth, GSK, Jazz, and MedAvante and holds stock in MedAvante; he receives research support from Lilly and study drug for an NIMH-funded study from Lilly and Pfizer. The other authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

Contributor Information

Rachel H. Jacobs, Department of Psychiatry, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

Susan G. Silva, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center

Mark A. Reinecke, Department of Psychiatry, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

John F. Curry, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University

Golda S. Ginsburg, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Christopher J. Kratochvil, Department of Psychiatry, University of Nebraska Medical Center

John S. March, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University

REFERENCES

- Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB. Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review. 1998;96:358–372. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerson J, Scogin F, McKendree-Smith N, Lyman R. Cognitive bibliotherapy for mild and moderate adolescent depressive. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:685–690. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Washington, DC: Author; Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (4th ed.) 1994

- Beck AT. Depression: Clinical, experimental and theoretical aspects. New York: Harper & Row; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ, Ford RQ. Therapeutic change: An object relations perspective. New York: Plenum; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ, Quinlan DM, Pilkonis PA, Shea MT. Impact of perfectionism and need for approval on the brief treatment of depression: The National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program revisited. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:125–132. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boergers J, Spirito A, Donaldson D. Reasons for adolescent suicide attempts: associations with psychological functioning. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:1287–1293. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199812000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booij L, Van der Does AJW. Cognitive and serotonergic vulnerability to depression: Convergent findings. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:86–94. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GP, Beck AT. Dysfunctional attitudes, perfectionism, and models of vulnerability to depression. In: Flett GL, Hewitt PL, editors. Perfectionism: Theory research, and treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 231–251. [Google Scholar]

- Cane DB, Olinger LJ, Gotlib IH, Kuiper NA. Factor structure of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale in a student population. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1986;42:307–309. [Google Scholar]

- Chang EC. Cultural differences, perfectionism, and suicidal risk in a college population: Does social problem solving still matter? Cognitive Therapy & Research. 2000;22:237–254. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DA, Beck AT. Cognitive theories and therapy. London: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA. Preliminary support for a competency-based model of depression in children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:181–190. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox BJ, Enns MW. Relative stability of dimensions of perfectionism in depression. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 2003;35(2):124–132. [Google Scholar]

- Dean PJ, Range LM, Goggin WC. The escape theory of suicide in college students: testing a model that includes perfectionism. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior. 1996;26:181–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson D, Spirito A, Farnett E. The role of perfectionism and depressive cognitions in understanding the hopelessness experienced by adolescent suicide attempters. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2000;31:99–111. doi: 10.1023/a:1001978625339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein DA, Lovibond PF, Gaston JE. Relationship between perfectionism and emotional symptoms in an adolescent sample. Australian Journal of Psychology. 2000;52:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Weiss B, Shanley N. Cognition, depressive symptoms, and development in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:47–57. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzegorek JL, Slaney RB, Franze S, Rice KG. Self-criticism, dependency, self-esteem, and grade point average satisfaction among clusters of perfectionists and nonperfectionists. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2004;51:192–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL. Stability of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression in youth: An examination of the trait-structure in a multi-wave longitudinal study. Paper presented at the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; Washington, DC. 2005. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Hawley LL, Ho MH, Zuroff DC, Blatt SJ. The relationship of perfectionism, depression, and therapeutic alliance during treatment for depression: Latent difference score analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:930–942. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt PL, Flett GL. Dimensions of perfectionism in unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991a;100:98–101. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt PL, Flett GL. Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1991b;60:456–470. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.60.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt PL, Flett GL. Personality traits and the coping process. In: Zeidner M, Endler NS, editors. Handbook of coping: Theory applications. London: Wiley; 1996. pp. 410–433. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt PL, Flett GL, Turnbull-Donovan W. Perfectionism and suicide potential. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1992;31:181–190. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1992.tb00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt PL, Flett GL, Weber C. Dimensions of perfectionism and suicide ideation. Cognitive Therapy & Research. 1994;18:439–460. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt PL, Newton J, Flett GL, Callander L. Perfectionism and suicide ideation in adolescent psychiatric patients. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25:95–101. doi: 10.1023/a:1025723327188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imber SD, Pilkonis PA, Sotsky SM, Elkin I, Watkins J, Collins JF, et al. Mode-specific effects among three treatments for depression. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:352–359. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram RE, Miranda J, Segal Z. Cognitive vulnerability to depression. In: Alloy LB, Riskind JH, editors. Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders. Mahweh, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2006. pp. 63–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Nock MK. Delineating mechanisms of change in child and adolescent therapy: Methodological issues and research recommendations. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 2003;44:1116–1129. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archive of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Hops H, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Andrews JA. Adolescent psychopathology, I: Prevalence and incidence of depression and other DSM–III–R disorders in high school students. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:133–144. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RA, Kazarian SS, Breiter HJ. Perceived stress, life events, dysfunctional attitudes, and depression in adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessments. 1995;17:81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Marton P, Kutcher S. The prevalence of cognitive distortion in depressed adolescents. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 1993;20:33–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver JM, Baumgart BP. The Dysfunctional Attitude Scale: Psychometric properties in an unselected adult population. Cognitive Theory and Research. 1985;9:161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Powers TA, Zuroff DC, Topciu RA. Covert and overt expressions of self-criticism and perfectionism and their relation to depression. European Journal of Personality. 2004;18:61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski EO, Mokros HB. Children’s depression rating scale–revised manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rey JM, Starling J, Wever C, Dossetor DR, Plapp JM. Inter-rater reliability of global assessment of functioning in a clinical setting. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1995;36:787–792. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. About my life, grades 7–9. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rice KG, Ashby JS, Slaney RB. Self-esteem as a mediator between perfectionism and depression: A structural equations analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1998;45:304–314. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers G, Essex M, Park J, Klein M, Curry JF, Feeny N, et al. The Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale: Psychometric properties in depressed adolescents. Journal of Clinical & Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:781–789. doi: 10.1080/15374410903259007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahar G, Blatt SJ, Zuroff DC. Satisfaction with social relations buffers the adverse effect of (mid-level) self-critical perfectionism in brief treatment for depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2007;26:540–555. [Google Scholar]

- Simons AD, Garfield SL, Murphy GE. The process of change in cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression: Changes in mood and cognition. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1984;41:45–51. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790120049007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study Team. Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): Rationale, design, and methods. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(5):531–542. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046839.90931.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) Team. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;292:807–820. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.7.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) Team. The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): Demographic and clinical characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44:28–40. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000145807.09027.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weersing VR, Weisz JR. Mechanisms of action in youth psychotherapy. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:3–29. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman AN, Beck AT. Development and validation of the dysfunctional Attitude Scale: A preliminary investigation. Paper presented at the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy; Chicago. 1978. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Williams S, Connolly J, Segal ZV. Intimacy in relationships and cognitive vulnerability to depression in adolescent girls. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25:477–496. [Google Scholar]

- Zuroff DC, Blatt SJ. Vicissitudes of life after the short-term treatment of depression: Roles of stress, social support, and personality. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2002;21:473–496. [Google Scholar]