Abstract

15N NMR chemical shift changes in the presence of Mg(H2O)62+, Zn2+, Cd2+, and Co(NH3)63+ were used to probe the effect of flanking bases on metal binding sites in three different RNA motifs. We found that: for GC pairs, the presence of a flanking purine creates a site for the soft metals Zn2+ and Cd2+ only; a GG·UU motif selectively binds only Co(NH3)63+, while a UG·GU motif binds none of these metals; a 3′ guanosine flanking the adenosine of a sheared GA·AG pair creates an unusually strong binding site that precludes binding to the cross-strand stacked guanosines within the tandem pair.

Keywords: RNA metal binding, 15N NMR, 15N labeling

INTRODUCTION

Metals play a crucial role in forming and maintaining the complex tertiary structure of RNA, as well as in all aspects of its function.1-6 Although much of the metal binding is non-specific and primarily serves to neutralize the phosphate negative charge, selective interactions with metals can occur when RNA folds into a precise geometry that provides an array of correctly oriented ligands. While many examples using X-ray crystallography have provided informative, although static, pictures of metals in such high-affinity sites,7-14 binding in solution is far more difficult to assess.

15N NMR chemical shifts are very sensitive to changes in the local environment around 15N atoms in labeled nucleic acids.15 As a result, 15N NMR of RNA containing specifically 15N-labeled nucleosides is a valuable non-perturbing probe for metal binding to nucleic acid nitrogen atoms.16 In particular, we have used N7 labeled guanosine to show that a sheared tandem GA pair with an adjacent guanosine17 and a tandem GU pair18 display strikingly different metal binding properties. The latter selectively binds Co(NH3)63+ and K+ with moderate affinity, but not Mg(H2O)62+, Zn2+, or Cd2+, while the former selectively binds Mg(H2O)62+, Zn2+ and Cd2+ with high affinity, but not Co(NH3)63+.

Using 15N NMR, we now describe results that explore the extent to which flanking bases modulate metal binding in three different small RNA motifs: GC pairs, tandem GU pairs, and tandem GA pairs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis of labeled RNA

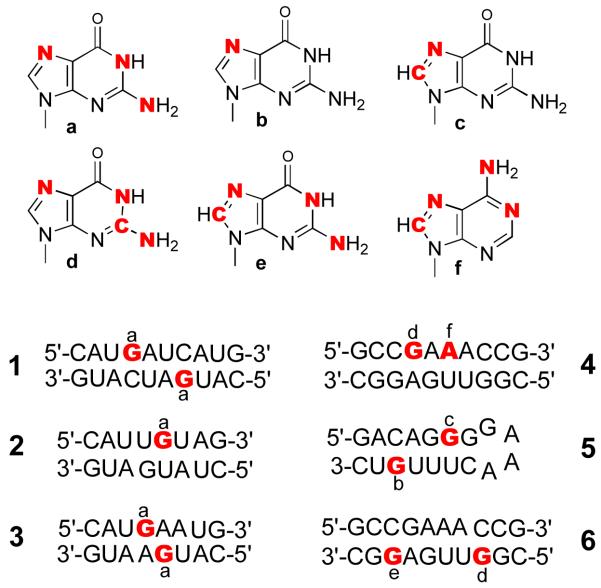

[1,7,NH2-15N3]-Guanosine (a), [7-15N]-guanosine (b), [8-13C-7-15N]-guanosine (c), [2-13C-1,7,NH2-15N3]-guanosine (d), [8-13C-1,7,NH2-15N3]-guanosine (e), and [8-13C-1,7,NH2-15N3]-adenosine (f) were synthesized as previously described.19-23 Each labeled nucleoside was protected with a phenoxyacetyl group on the amino, a dimethoxytrityl group on the 5′ OH, and a tertbutyldimethylsilyl group on the 2′ OH.24,25 After conversion to cyanoethyl phosphoramidites, they were incorporated into RNA on an OligoPilot II synthesizer on 60 μmol scales. Figure 1 indicates the sites at which various labeled nucleosides were incorporated. Duplexes 1–4 are reported here for the first time, while 518 and 617 have previously been described, and are included for comparison. The crude oligonucleotides were deprotected with 40% methylamine, then Et3N·3HF/Et3N/N-methylpyrrolidinone.26 The excess fluoride was scavenged with isopropyltrimethylsilyl ether.27 The precipitated RNA was dissolved in 0.1 M triethylammonium acetate at pH 6.8 and purified by reversed phase HPLC, before and again after detritylation. The pure RNA was desalted by reversed phase HPLC using 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate, and then converted to the sodium form on a cation exchange column.

Figure 1.

Specifically labeled RNA molecules 1–6 synthesized with the designated specifically labeled nucleosides a-f. Molecules 5 and 6 have previously been reported, and are included for comparison. The labeled nucleosides are: a, [1,7,NH2-15N3]-guanosine; b, [7-15N]-guanosine; c, [8-13C-7-15N]-guanosine; d, [2-13C-1,7,NH2-15N3]-guanosine; e, [8-13C-1,7,NH2-15N3]-guanosine; and f, [8-13C-1,7,NH2-15N3]-adenosine.

NMR sample preparation

The total strand concentration in each sample was 6.0 mM for duplexes 1 and 3, 4.3 mM for duplex 2, and 3.0 mM for duplex 4. Previously reported 6 was 3.0 mM and 5 was 3.3 mM. They all contained 20 mM HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) and 50 mM NaCl in H2O with 10% D2O at pH 6.8. Duplexes 1 and 3 are self-complimentary, so were prepared directly from stock solutions, while the two different strands for duplexes 2 and 4 were combined in a 1:1 molar ratio. All samples were transferred to 300 mL Shigemi tubes. 1H NMR spectra acquired at 10 °C for duplexes 1–3 and 20 °C for duplex 4 demonstrated complete duplex formation. In duplex 2, the presence of a tandem GU wobble pair was indicated by resonances for exchangeable G and U protons between 10 and 11.7 ppm, and in duplex 3, the presence of a sheared tandem GA pair was indicated by a doublet at 11.7 ppm for the proton on the 15N-labeled GN1.

Addition of metal to NMR samples

Solutions of ultrapure MgCl2, ZnCl2, and Cd(NO3)2 (from Aldrich) and Co(NH3)6Cl3 (from Strem Chemicals) were prepared in water and appropriate aliquots were added to the RNA samples in centrifuge tubes. After lyophilization, 0.30 mL 90% H2O/10% D2O was added and the pH was adjusted to 6.8 following brief annealing.

NMR acquisition

15N NMR 1 D spectra were acquired at 30.4 MHz on a Varian Mercury 300 NMR spectrometer with a delay of 1 s for 12–16 hours. Spectra for duplexes 1–3 were acquired at 10 °C and duplex 4 at 20 °C. Spectra for previously reported 6 were acquired at 20 °C and those of 5 at 15 °C. Chemical shifts are reported relative to NH3 using external 1 M [15N]urea in DMSO at 77.0 ppm as a standard.28

RESULTS

We have synthesized four new duplexes specifically labeled with [1,7,NH2-15N3]-guanosine (a) or [2-13C-1,7,NH2-15N3]-guanosine (d), in one case with [8-13C-1,7,NH2-15N3]-adenosine (f) as well. The sequences of these new duplexes (1–4) are shown in Figure 1, along with those of two previously reported molecules, 518 and 617, that we include for comparison. Since 5 and 6 each have two different 15N-labeled guanosines, 13C labels are selectively included as tags to allow differentiation of the resonances. Although metal interactions are expected to be at guanosine N7 atoms, in most cases we labeled other nitrogens as well for comparison.

15N NMR chemical shift changes for 15N-labeled N7 atoms of GC pairs, tandem GU pairs, and tandem GA pairs upon addition of the four diamagnetic metals Mg(H2O)62+, Zn2+, Cd2+, and Co(NH3)63+ are shown in Table 2, followed by the number of equivalents of metal added, relative to labeled strand. With Zn2+, Cd2+, and Co(NH3)63+, we used stoichiometric amounts of the metal for each potential binding site, normally1 – 1.5 equiv, but when probing a motif in a molecule with a strong binding site elsewhere, we went to 2–3 equiv. Because of the low affinity of Mg(H2O)62+ for nitrogen, we used much larger amounts, ranging from 8 – 15 equiv, to probe Mg(H2O)62+ binding. Chemical shift changes for the N1 and amino nitrogens were < 2 ppm in all cases, and are not shown. Because the RNA sequences and conditions of the six samples are not identical, the comparisons we describe are intended to be qualitative rather than quantitative.

Table 2.

15N NMR chemical shift changes for the N7 atoms of 15N labeled nucleosides (shown in bold) in individual motifs in RNA 1–6 upon addition of various equivalents (relative to labeled strand) of four different metals. The motifs are shown 5′ to 3′ on top and 3′ to 5′ below. A negative sign for the chemical shift change indicates upfield and a positive sign indicates downfield

| RNA | motif | Δδ/equiv metal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg(H2O)62+ | Zn2+ | Cd2+ | Co(NH3)63+ | |||

| a | 518 | -UGU- -ACA- |

−0.8/8 | −0.6/1 | −0.6/1 | +1.6/3 |

| b | 617 | -GGU- -CCA- |

−1.2/15 | −5.9/2 | −9.0/2 | +1.1/2 |

| c | 1 | -UGA- -ACU- |

−1.3/10 | −3.3/1 | −6.8/1 | +0.6/1 |

| d | 518 | -AGGG- -UUUC- |

−0.3/8 | −1.0/1 | −2.0/1 | +5.3/1.5 |

| e | 2 | -UUGU- -AGUA- |

+0.3/10 | −0.1/1 | −0.3/1 | +0.1/1 |

| f | 617 | -CGAA- -GAGU- |

−6.5/10 | −17.5/1 | −17.3/1 | +0.5/1 |

| g | 4 | -CGAA- -GAGU- |

−1.1/15 | −0.8/2 | −0.8/2 | −0.3/2 |

| h | 4 | -CGAA- -GAGU- |

−0.8/15 | −2.9/2 | −3.4/2 | +0.4/2 |

| i | 3 | -UGAA- -AAGU- |

−1.0/10 | −10.64/1 | −12.4/1 | +3.0/1major +0.4/1minor |

For the GC pairs, we find that with uridines flanking the guanosine (row a), chemical shift changes for its N7 upon addition of all four metals are small (≤1.6 ppm). However, with a flanking guanosine (row b) or adenosine (row c), we observe moderate changes (3–9 ppm) with Zn2+ and Cd2+, but small changes with Mg(H2O)62+ and Co(NH3)63+ (≤1.3 ppm).

For two different arrangements of a tandem GU motif (rows d and e), small changes are found with Mg(H2O)62+, Zn2+, and Cd2+ (≤2 ppm). In these cases, different flanking bases do not influence the results. With Co(NH3)63+, a significant change (5 ppm) occurs for the GG·UU motif (row d), but only a very small change (0.1 ppm) is found for the UG·GU motif (row e).

A 3′ guanosine adjacent to an adenosine of a sheared GA·AG pair (row f) displays strikingly large changes with Mg(H2O)62+ (6.5 ppm), Zn2+, and Cd2+ (17 ppm), but not with Co(NH3)63+ (0.5 ppm).17 However, a 3′ adenosine in a comparable position (row g) shows only small changes for all metals (≤1.1 ppm). A guanosine within the sheared tandem GA pair (row h) with the nearby strong binding site created by a 3′ flanking guanosine shows modest changes with Zn2+ and Cd2+ (3–4 ppm), but only small changes with Mg(H2O)62+ and Co(NH3)63+ (≤0.8 ppm). In contrast, a sheared GA·AG pair with two 3′ flanking adenosines (row i) displays relatively large changes with Zn2+ and Cd2+ (9–12 ppm) and a moderate change with Co(NH3)63+ (3 ppm), but only a small change with Mg(H2O)62+ (1 ppm). The spectrum for duplex 3 with Co(NH3)63+ displays two N7 resonances, the major one downfield of the minor one.

DISCUSSION

15N NMR is an excellent method for probing interactions at purine sp2 nitrogens when they are 15N-labeled.15 It has long been known that addition of excess amounts of soft metals like Zn2+ and Hg2+ that can accommodate inner-sphere binding to ligands cause ~20 ppm upfield changes for the guanosine N7.29 We have demonstrated similar upfield changes with Zn2+ and Cd2+ at a labeled guanosine N7 in a RNA duplex decamer that was designed to model a known metal binding site near a sheared tandem GA pair in stem II of a minimal hammerhead ribozyme.17 We have also reported smaller upfield changes (typically 2–9 ppm) upon formation of hydrogen bonds by purine N1 or N7 atoms in duplexes and triplexes.30-32 Although the hard metal Mg(H2O)62+ with its unusually tight hydration layer normally does not interact selectively with nitrogen atoms, in X ray structures of a minimal hammerhead stem II, a guanosine N7 is precisely positioned near a phosphate from a sheared tandem GA pair and participates in the resulting strong Mg(H2O)62+ binding site7,12. We observed a selective 6.5 ppm upfield change for the labeled guanosine N7 at this site upon addition of Mg(H2O)62+,17 consistent with unusually strong hydrogen bonding of the N7 with the tight hydration layer of Mg(H2O)62+.

In contrast, we have observed small downfield chemical shift changes for the purely electrostatic effects of Na+.18 We have also reported downfield changes for Co(NH3)63+: a small non-selective change in the hammerhead model17 and a larger, selective change at a tandem GU pair.18 Since the ammine ligands in Co(NH3)63+ exchange extremely slowly, the downfield changes we have observed are consistent with a combination of the strong electrostatic effect of trivalent Co3+, and hydrogen bonding to the N7 that is weaker with ammine ligands than with solvent water.33 Thus, while the direction of 15N chemical shift change upon addition of various metals is a consequence of their individual properties, it is the magnitude of the change that reflects the degree of selectivity. Further, the possible magnitudes for the chemical shift changes vary with the metal, since the direct inner-sphere interactions with Zn2+ and Cd2+ have a greater effect than the outer-sphere hydrogen bonding with Mg(H2O)62+ and the electrostatic effects of Co(NH3)63+. Consequently, our discussion below focuses only on the relative magnitude of the changes.

Of the four diamagnetic metals used in these studies, only Mg(H2O)62+ is biologically abundant. However, a comparison of results from all four can take advantage of their different modes of interaction with RNA metal binding sites, and thus allows a more complete interpretation. This information could prove particularly useful for engineering new artificial RNA systems. Using the framework provided by the key examples of 15N NMR chemical shift changes that we have already reported,17,18 we are now in a position to extend this approach to the effects of flanking bases on metal binding to GC pairs, tandem GU pairs, and tandem GA pairs.

GC pairs

We have previously reported that the N7 of a GC pair in hairpin 5 with two uridines flanking the guanosine displays small changes (≤1.6 ppm) upon addition of these four metals (row a).18 We have also shown that the GG·UU motif elsewhere in this molecule does not selectively bind Mg(H2O)62+, Zn2+, or Cd2+, although it does selectively bind Co(NH3)63+. None-the-less, even in the presence of excess Co(NH3)63+ (3 equiv), the GC pair with uridines flanking the guanosine only shows a small change.

We have also previously reported results for a GC pair with a 5′G and a 3′U flanking the labeled guanosine (G[d]) in duplex 6 that has a strong binding site elsewhere in the molecule at G[e].17 Using excess metal, we found that the guanosine of this GC pair (G[d]) displays significant changes with the soft metals Zn2+ (6 ppm) and Cd2+ (9 ppm) (row b), but quite small changes with Mg(H2O)62+ (1.2 ppm) and Co(NH3)63+ (1.1 ppm). Thus, a simple GC pair with a flanking guanosine can form a binding site that attracts soft metals with moderate affinity.

We now present results for a GC pair in 1, which does not contain another binding site (row c). The labeled guanosine of the GC pair has 5′U and 3′A flanking bases. Although the changes with Mg(H2O)62+ and Co(NH3)63+ are small (≤1.3 ppm), the changes with Zn2+ (3 ppm) and Cd2+ (7 ppm) are substantial, indicating that an adjacent adenosine N7 can also help to create a moderately strong binding site for the softer metals, even though it is less basic than guanosine N7. These results demonstrate that two adjacent purines in a region of RNA with standard A form geometry are sufficient to create a binding site for the softer metals that interact through inner-sphere binding to the two closely positioned N7 atoms. However, Mg(H2O)62+ and Co(NH3)63+ with their very tight solvation layers cannot bind to these sites.

Tandem GU motifs

Using 15N NMR, we have reported selective K+ and Co(NH3)63+ binding to a GG·UU motif in hairpin 518 to which Co(NH3)63+ had already been known to bind34. Although Mg(H2O)62+ and Co(NH3)63+ have been proposed to bind to the same RNA motifs because of their similar size and geometry,35 we found 15N NMR evidence (row d) for selective binding by Co(NH3)63+ (5 ppm), but not for Mg(H2O)62+, Zn2+, or Cd2+ (≤2.0 ppm). In this GG·UU motif, two guanine N7 atoms and two O6 atoms, but no phosphates, form a broad cavity in the major groove with uniform negative electrostatic potential to which trivalent metal hexamines are attracted by outer-sphere binding and K+ is attracted because its loose and flexible hydration layer is easily displaced.18 We now report quite different results for a UG·GU motif in duplex 2 (row e). In this case, the change with Co(NH3)63+ is very small, like those with Mg(H2O)6, Zn2+, and Cd2+ (≤0.3 ppm).

Using 1H NMR, Colmenarejo and Tinoco had earlier compared Co(NH3)63+ binding to three different tandem GU motifs and found the order of affinity to be GU·UG ~ GG·UU > UG·GU.36 His modeling showed that for the latter, Co(NH3)63+ was not accommodated as well into the major groove. Our results definitively support this order of affinity, with the large 5 ppm change for GG·UU demonstrating significant binding, and the very small 0.1 ppm change for UG·GU indicating negligible binding. Thus the arrangement within the tandem GU pair is critical for metal binding, while we see no evidence that the flanking bases play a significant role.

Duplex 2 is the only example we have seen in which the change for Mg(H2O)62+ is downfield. We conclude that in this case, no phosphate is close enough to the guanosine N7 to allow hydrogen bonding with the hydration layer of Mg(H2O)62+, and the downfield change is a purely electrostatic effect.

Tandem GA motifs

We previously used 15N NMR to describe unusually strong, selective binding by Mg(H2O)62+, Zn2+,and Cd2+, but not Co(NH3)63+, to a high-affinity site at a guanosine (G[e]) adjacent to a sheared tandem GA pair in a duplex model (6) of part of stem II of a minimal hammerhead ribozyme.17 The large chemical shift changes (row f) with Mg(H2O)62+ (6.5 ppm), Zn2+ (17 ppm), and Cd2+ (17 ppm) serve to define very strong binding for these metals as measured by 15N NMR.

We now report results for the same model duplex, but instead with two labeled nucleosides in the strand opposite the binding site, 4. The labeled adenosine in 4 is in a symmetrical position relative to the tandem GA pair as is the strong binding site at G[e] in 6. This adenosine N7 shows limited affinity (≤ 1 ppm) for all four metals (row g), even with excess metal, contrary to an earlier proposal that it might be a strong binding site.37 Thus, although the N7 of a flanking adenosine can help create a binding site for soft metals adjacent to a GC pair in standard A form geometry (row c), it does not do so with the altered geometry of a sheared tandem GA pair.

Formation of a sheared GA·AG pair results in characteristic hydrogen bonds between the G amino and the AN7 and between the GN3 and the A amino, as well as cross-strand stacking of G on G and A on A.38-40 In this unusual geometry, the N7 and O6 atoms of the two cross-strand stacked guanosines are closely aligned, and might form a metal binding site in the absence of a stronger one nearby. Duplex 4 with a labeled internal guanosine has a strong binding site in the opposite strand that involves the 3′ flanking guanosine (G[e] in 6). Even with excess metal (row h), we observe only small changes (≤0.8 ppm) for the internal guanosine in 4 with Mg(H2O)62+ and Co(NH3)63+, and modest changes (3 ppm) with Zn2+ and Cd2+.

In contrast, duplex 3 has a sheared GA·AG pair with no additional binding sites because it has 3′ flanking adenosines on both sides (row i). While the change with Mg(H2O)62+ is small (1 ppm), the change for the major resonance with Co(NH3)63+ is moderate (3 ppm) and those with Zn2+ (9 ppm) and Cd2+ (12 ppm) are significant. While not of the 17 ppm magnitude seen at G[e] in 6 (row f), the results in row i reflect affinities that are somewhat larger than to two adjacent GC pairs (row b) and much larger than to isolated GC pairs (row a). Further, the spectrum for duplex 3 with Co(NH3)63+ is unique among all those reported here in displaying an additional minor N7 resonance with only a 0.4 ppm change. These results presumably reflect the presence of two different conformational forms in slow exchange that bind Co(NH3)63+ to different extents.

CONCLUSION

The RNA molecules described here contain three common types of small motifs that can bind metals in different ways: GC pairs, tandem GU pairs, and tandem GA pairs. A comparison of their 15N NMR chemical shift changes in the presence of added metal demonstrates the important roles that flanking bases can have, in some cases but not others, on the nature and extent of metal binding to sites containing guanosine N7 atoms. For GC pairs in standard A form geometry, uridines flanking the guanosine have no effect on the limited metal binding, while either a flanking guanosine or adenosine significantly increases binding of the soft metals Zn2+ and Cd2+, but not the harder Mg(H2O)62+ or Co(NH3)63+. Tandem GU and GA pairs have altered geometries that play a significant role in their binding to metals. Of the four metals studied here, the GG·UU motif preferentially binds Co(NH3)63+, while the UG·GU motif does not bind any of the metals. Metal binding to sheared GA·AG pairs is profoundly affected by the flanking bases. With a 3′ guanosine flanking one of the adenosines, an unusually strong binding site for Mg(H2O)62+, Zn2+, and Cd2+, but not Co(NH3)63+, is created that involves that guanosine N7 and a phosphate from the tandem pair. This high-affinity site precludes any significant binding of metals to the cross-strand stacked guanosines within the tandem pair. On the other hand, a 3′ flanking adenosine does not create a comparable high-affinity site. In this case, the cross-strand stacked guanosines within the tandem pair can therefore attract soft metals as well as Co(NH3)63+ to their closely aligned N7 and O6 atoms with surprising affinity, while the lack of a close phosphate prevents Mg(H2O)62+ from being attracted. For these biologically common motifs,41,42 a qualitative comparison of 15N NMR chemical shift changes with the four metals described here has provided valuable insight into the differences among their metal binding affinities and the varying effects of flanking bases.

Table 1.

15N NMR chemical shifts in ppm for 15N labeled N7 atoms in molecules 1–6

| RNA | no metal | Mg(H2O)62+ | Zn2+ | Cd2+ | Co(NH3)63+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 234.87 | 233.54 | 231.61 | 228.12 | 235.43 |

| 2 | 234.90 | 235.19 | 234.78 | 234.58 | 235.03 |

| 3 | 234.90 | 233.86 | 224.26 | 222.49 | 237.89/235.31 |

| 4G | 233.74 | 232.94 | 230.85 | 230.37 | 234.14 |

| 4A | 228.64 | 227.55 | 227.84 | 227.79 | 228.32 |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from NIH (GM79760).

Footnotes

In honor of and in celebration of Morris J. Robins’ 70th birthday

REFERENCES

- 1.Doudna JA, Cech TR. The chemical repertoire of natural ribozymes. Nature (London) 2002;418:222–228. doi: 10.1038/418222a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeRose VJ. Two decades of RNA catalysis. Chem. Biol. 2002;9:961–969. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00217-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fedor MJ. The role of metal ions in RNA catalysis. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2002;12:289–295. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pyle AM. Metal ions in the structure and function of RNA. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2002;7:679–690. doi: 10.1007/s00775-002-0387-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woodson SA. Metal ions and RNA folding: a highly charged topic with a dynamic future. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2005;9:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Hashimi HM, Walter NG. RNA dynamics: It is about time. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2008;18:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scott WG, Finch JT, Klug A. The crystal structure of an all-RNA hammerhead ribozyme. Cell. 1995;81:991–1002. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cate JH, Hanna RL, Doudna JA. A magnesium ion core at the heart of a ribozyme domain. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1997;4:553–558. doi: 10.1038/nsb0797-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juneau K, Podell E, Harrington DJ, Cech TR. Structural basis of the enhanced stability of a mutant ribozyme domain and a detailed view of RNA-solvent interactions. Structure. 2001;9:221–231. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00579-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nissen P, Hansen J, Ban N, Moore PB, Steitz TA. The structural basis of ribozome activity in peptide bond synthesis. Science. 2000;289:920–9930. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Misra VK, Draper DE. The linkage between magnesium binding and RNA folding. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;317:507–521. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2002.5422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pley HW, Flaherty KM, McKay DB. Three-dimensional structure of a hammerhead ribozyme. Nature (London) 1994;372:68–74. doi: 10.1038/372068a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martick M, Scott WG. Tertiary contacts distant from the active site prime a ribozyme for catalysis. Cell. 2006;126:309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toor N, Keating KS, Taylor SD, Pyle AM. Crystal structure of a self-spliced group II intron. Science (Wash.) 2008;320:77–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1153803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy GC. Nitrogen-15 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka Y, Ono A. Nitrogen-15 NMR spectroscopy of N-metallated nucleic acids: insights into 15N NMR parameters and N-metal bonds. Dalton Transactions. 2008:4965–4974. doi: 10.1039/b803510p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang G, Gaffney BL, Jones RA. Differential binding of Mg2+, Zn2+, and Cd2+ at two sites in a hammerhead ribozyme motif, determined by 15N NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:8908–8909. doi: 10.1021/ja049804v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan Y, Gaffney BL, Jones RA. RNA GG·UU motif binds K+ but not Mg2+ J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:17588–17589. doi: 10.1021/ja0555522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pagano AR, Lajewski WM, Jones RA. Syntheses of [6,7-15N]-Adenosine, [6,7-15N]-2′-Deoxyadenosine, and [7-15N]-Hypoxanthine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:11669–11672. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao H, Pagano AR, Wang W, Shallop A, Gaffney BL, Jones RA. Use of a 13C atom to differentiate two 15N-labeled nucleosides. Synthesis of [15NH2]-adenosine, [1,NH2-15N2]- and [2-13C-1,NH2-15N2]-guanosine, and [1,7,NH2-15N3]- and [2-13C-1,7-NH2-15N3]-2′-deoxyguanosine. J. Org. Chem. 1997;62:7832–7835. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pagano AR, Zhao H, Shallop A, Jones RA. Syntheses of [1,7-15N2]- and [1,7,NH2-15N3]-adenosine and 2′-deoxyadenosine via an N1-alkoxy mediated Dimroth rearrangement. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:3213–3217. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shallop AJ, Gaffney BL, Jones RA. Use of 13C as an Indirect Tag in 15 N Specifically Labeled Nucleosides. Syntheses of [8-13 C-1,7,NH 2-15 N3]-Adenosine, -Guanosine, and their Deoxy Analogs. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:8657–8661. doi: 10.1021/jo0345446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lagoja I, Herdewijn P. Chemical sythesis of 13C and 15N labeled nucleosides. Synthesis. 2002;2002:301–314. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Song Q, Wang W, Fischer A, Zhang X, Gaffney BL, Jones RA. High yield protection of purine ribonucleosides for phosphoramidite RNA synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:4153–4156. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Serebryany V, Beigelman L. An efficient preparation of protected ribonucleosides for phosphoramidite RNA synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:1983–1985. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wincott F, DeRenzo A, Shaffer C, Grimm S, Tracz D, Workman C, Sweedler D, Gonzalez C, Scaringe S, Usman N. Synthesis, deprotection, analysis and purification of RNA and ribozymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2677–2684. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.14.2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song Q, Jones RA. Use of silyl ethers as fluoride scavengers in RNA synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:4653–4654. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wishart DS, Bigam CG, Yao J, Abildgaard F, Dyson HJ, Oldfield E, Markley JL, Sykes BD. 1H, 13C and 15N chemical shift referencing in biomolecular NMR. J. Biomolecular NMR. 1995;6:135–140. doi: 10.1007/BF00211777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buchanan GW, Stothers JB. Diamagnetic metal ion-nucleoside interactions in solution as studied by 15N nuclear magnetic resonance. Can. J. Chem. 1982;60:787–791. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao X, Jones RA. Nitrogen-15-labeled oligodeoxynucleotides. Characterization by 15N NMR of d[CGTACG] containing 15N1- or 15N6-labeled deoxyadenosine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:3169–3171. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaffney BL, Goswami B, Jones RA. Nitrogen-15-labeled oligodeoxynucleotides. 7. Use of 15N NMR to probe H-bonding in an O6MeG·C base pair. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:12607–12608. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaffney BL, Kung P-P, Wang C, Jones RA. Nitrogen-15-labeled oligodeoxynucleotides. 8. Use of 15N NMR to probe Hoogsteen hydrogen bonding at guanine and adenine N-7 atoms of a DNA triplex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:12281–12283. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Black CB, Cowan JA. Quantitative evaluation of electrostatic and hydrogen-bonding contributions to metal cofactor binding to nucleic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:1174–1178. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kieft JS, Tinoco I., Jr. Solution structure of a metal-binding site in the major groove of RNA complexed with cobalt (III) hexammine. Structure. 1997;5:713–721. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00225-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cowan JA. Metallobiochemistry of RNA. Co(NH3)63+ as a probe for Mg2+(aq) binding sites. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1993;49:171–175. doi: 10.1016/0162-0134(93)80002-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colmenarejo G, Tinoco I., Jr. Structure and thermodynamics of metal binding in the P5 helix of a group I intron ribozyme. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;290:119–135. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hansen MR, Simorre J-P, Hanson P, Mokler V, Bellon L, Beigelman L, Pardi A. Identification and characterization of a novel high affinity metal-binding site in the hamerhead ribozyme. RNA. 1999;5:1099–1104. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299990738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.SantaLucia J, Turner DH. Structure of (rGGCGAGCC)2 in solution from NMR and restrained molecular dynamics. Biochemistry. 1993;32:12612–12623. doi: 10.1021/bi00210a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katahira M, Kanagawa M, Sato H, Uesugi S, Fujii S, Kohno T, Maeda T. Formation of sheared GA base pairs in an RNA duplex modelled after ribozymes, as revealed by NMR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2752–2759. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.14.2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heus HA, Wijmenga SS, Hoppe H, Hilbers CW. The detailed structure of tandem GA mismatched base-pair motifs in RNA duplexes is context dependent. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;271:147–158. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gautheret D, Konings D, Gutell RR. A major family of motifs involving GA mismatches in ribosomal RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;242:1–8. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gautheret D, Konings D, Gutell RR. GU base pairing motifs in ribosomal RNA. RNA. 1995;1:807–814. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]