Abstract

Interatrial septal hematoma is a very rare complication after mitral valve surgery. Unusually, it is the result of aortic valve disease, including aortic dissection. We report a case wherein interatrial septal hematoma followed minimally invasive aortic valve replacement in a 68-year-old woman. The hematoma was recognized upon intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography, but there was no evidence of accompanying aortic dissection. The interatrial septal hematoma was at first drained by needle, but recurrence prompted reoperation and plication of the interatrial septum. Finally, the hematoma resolved after correction of the coagulopathy. Catheter injury to the coronary sinus exacerbated by the retrograde administration of cardioplegic solution is thought to have caused the origin of the interatrial septal dissection.

Interatrial septal (IAS) hematoma is a very rare sequela to mitral valve surgery. To the best of our knowledge, it has not heretofore been reported after minimally invasive aortic valve surgery. The most common cause is mitral annular disruption that extends into the IAS and then into a low-pressure chamber—either the right or left atrium (LA)—via fistulation. Less commonly, aortic dissection can penetrate the LA via fistulation through the anterior IAS. We report the development and successful management of an IAS hematoma that followed minimally invasive aortic valve replacement, in the absence of aortic dissection.

Case Report

In October 2007, a 68-year-old woman with a history of moderate aortic stenosis presented at our institution with worsening dyspnea on exertion. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed severe aortic stenosis with an aortic valve area of 0.5 cm2, a transvalvular peak gradient of 105 mmHg, and a mean gradient of 64 mmHg. Preoperative cardiac catheterization documented normal coronary arteries, normal left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction, and an LV outflow tract diameter of 18 mmHg.

Through a partial upper median sternotomy, routine cannulation for extracorporeal circulation was performed, with the arterial cannula in the ascending aorta and a 2-stage venous cannula in the right atrial appendage. Cardioplegic cannulae were inserted into the ascending aorta (antegrade) and into the coronary sinus. An LV vent was inserted through the right superior pulmonary vein into the LA, and this was confirmed upon transesophageal echocardiography (TEE). The aortic valve was replaced with a 19-mm Carpentier-Edwards PERIMOUNT™ Magna™ pericardial valve (Edwards Lifesciences LLC; Irvine, Calif), which was sewn to the aortic annulus in the usual manner. Return of blood effluent from both of the coronary orifices was confirmed after implantation of the valve. To accommodate the struts of the bioprosthesis, the ascending aorta above the level of the sinotubular junction was augmented with a pericardial patch. The patient was weaned from cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) with good biventricular function. Protamine reversal of heparin was completed, and the ministernotomy was closed. After this, the patient experienced a bradycardiac arrest.

The ministernotomy was converted to a full sternotomy, and CPB was reinstituted, following reheparinization. Saphenous vein grafts were placed empirically, to the right and left anterior descending coronary arteries. The patient was successfully weaned from CPB with good biventricular function. Heparin was reversed with protamine. However, the TEE showed a mass in the LA, rapidly encroaching upon the mitral valve orifice (Fig. 1). We diagnosed IAS hematoma, the origin of which appeared to be the right superior pulmonary vein.

Fig. 1 Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiogram shows left atrial dissection flap (arrow) bowing towards the mitral annulus. LA = left atrium; LV = left ventricle; MV = mitral valve; RA = right atrium; RV = right ventricle

Because the hematoma was rapidly causing mitral inflow obstruction, we performed needle aspiration through the right atrium, under TEE guidance. The hematoma disappeared after aspiration, and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit.

A repeat echocardiogram performed 6 hours postoperatively revealed that the IAS hematoma had recurred. However, there was no evidence of aortic dissection into the IAS, and coronary sinus blood flow, as well as right superior pulmonary vein flow, was normal. Over the next few hours, the patient's hemodynamic status worsened, prompting a return to the operating room for evacuation of the hematoma.

Under full CPB support, the IAS was incised through a right atriotomy, and the hematoma was evacuated. The exact origin of the dissection was unclear; however, the hematoma surrounded the coronary sinus orifice. The edges of the dissected IAS were reapproximated with pledgeted Prolene sutures. The atrial septal defect was closed directly with running Prolene sutures. No recurrence of hematoma was observed after complete reversal of heparin with protamine.

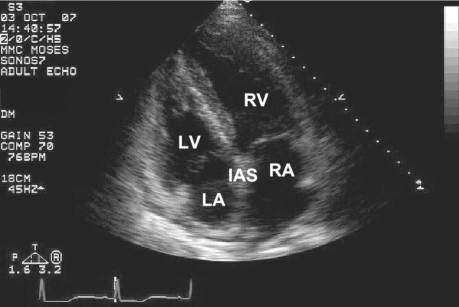

The patient continued to have a difficult postoperative course. Initial TEE showed recurrence of the IAS hematoma. This resolved over the next 3 weeks (Fig. 2). The postoperative course was complicated by atrial fibrillation on day 18. The patient recovered and was discharged 24 days postoperatively. She remained well and was asymptomatic at her follow-up visit, 5 months later.

Fig. 2 Three weeks after surgery, transesophageal echocardiogram shows that the left atrial dissection has been obliterated. IAS = interatrial septum; LA = left atrium; LV = left ventricle; RA = right atrium; RV = right ventricle

Discussion

Interatrial septal hematomas have been reported, uncommonly, in peer-reviewed literature (Table I).1–17 The increasing use of transatrial interventional procedures, including device closure of atrial septal defects, raises the possibility that these IAS hematomas will become more common. Historically, treatment has varied from conservative management, with or without anticoagulation, to surgery.

TABLE I. Review of Published Reports of Interatrial Septal Hematoma and Left Atrial Dissection

Correction of coagulopathy, afterload reduction, and early antiarrhythmic therapy are managed post-operatively. Resolution of the hematoma can be monitored by means of serial echocardiography. Reaccumulation of blood can follow surgical evacuation and might necessitate additional surgical procedures for drainage.

The commonest iatrogenic cause of IAS hematoma is mitral valve surgery (0.84%) (Table I). In such cases, the cause is usually disruption of the posterior annulus after over-resection of the mural leaflet.14 This is especially common in elderly women who have a heavily calcified annulus and a small LV. Hematoma has also been reported, after separation of the anterior mitral annulus from the aortomitral curtain, due to infective endocarditis.6 Rarely, the dissection originates in a pulmonary vein and causes pulmonary venous obstruction and acute pulmonary edema.11

Repair of the dissection has been performed either by marsupialization of the IAS into the right atrium8 or by closure of entry and exit points,16 along with buttressing of the IAS.10,12 Marsupialization alone may result in a minor residual left-to-right shunt.8 Conservative management, with close observation, has also been successful in some cases.5

Gallego and colleagues6 reported the largest case series, which comprised 11 patients with left atrial dissection. Most of these lesions were a result of mitral valve surgery and might be classified as type I left ventricular rupture.

Uncommon events that cause IAS hematomas include resection of a right ventricular mass, coronary sinus cannulation,6 and ventricular septal rupture. Other iatrogenic causes of LA hematoma include pericardial puncture and insertion of a permanent pacemaker. Interatrial septal hematomas have not been reported as a complication of LV vent placement.

In our patient, it is likely that a traumatic coronary sinus cannulation created an entry point for the dissection into the IAS. This dissection was then propagated by the retrograde administration of cardioplegic solution at pressures as high as 40 mmHg. We did not suspect a direct fistulous connection to the LA. Finally, it should be remarked that correction of the patient's coagulopathy resulted in resolution of the hematoma.

Surgeons should be aware of the possibility of IAS hematoma. Although no firm conclusions can be advanced, conservative management is reasonable as long as mitral stenosis does not add to the problem.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Reshma M. Biniwale, MD, Department of Cardiac Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California at Los Angeles, 10833 Le Conte Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90025

E-mail: rbiniwale@mednet.ucla.edu

References

- 1.Tasoglu I, Imren Y, Tavil Y, Zor H. Left atrial dissection following mass removal from right ventricle: non-surgical therapy. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2005;4(3):173–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Shimozato A, Kaneko Y, Kim M, Takeuchi H, Oguri A, Yonemura S, et al. Atrial wall hematoma after mitral valvuloplasty and maze procedure: a case report [in Japanese]. J Cardiol 2006;48(6):353–8. [PubMed]

- 3.Jani S, Hecht S, Leibowitz K, Berger M. Left atrial dissection: an unusual complication of mitral valve surgery. Echocardiography 2007;24(4):443–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Osawa H, Saitoh T, Sugimoto S, Takagi N, Abe T. Dissection of intima on atrial septum patch after mitral valve replacement in a patient with infective endocarditis after incomplete atrio-ventricular septal defect repair: report of a case. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2004;10(2):124–5. [PubMed]

- 5.Ninomiya M, Taketani T, Ohtsuka T, Motomura N, Takamoto S. A rare type of left atrial dissection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002;124(3):618–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Gallego P, Oliver JM, Gonzalez A, Dominguez FJ, Sanchez-Recalde A, Mesa JM. Left atrial dissection: pathogenesis, clinical course, and transesophageal echocardiographic recognition. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2001;14(8):813–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Schmid ER, Schmidlin D, Jenni R. Images in cardiology. Left atrial dissection after mitral valve reconstruction. Heart 1997;78(5):492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Genoni M, Jenni R, Schmid ER, Vogt PR, Turina MI. Treatment of left atrial dissection after mitral repair: internal drainage. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;68(4):1394–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Di Gregorio O, Nardi C, Milano A, De Carlo M, Grana M, Bortolotti U. Dissection of atrial septum after mitral valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;71(5):1670–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Pretre R, Murith N, Neidhart P, Luthi P, Faidutti B. Dissection of the atrial septum following mitral valve surgery. J Card Surg 1994;9(1):61–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Grech E, Morrison L, Weir I, Harley A. Acute pulmonary edema due to pulmonary venous obstruction by left atrial dissection. Am Heart J 1993;126(3 Pt 1):734–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Lukacs L, Kassai I, Lengyel M. Dissection of the atrial wall after mitral valve replacement. Tex Heart Inst J 1996;23(1): 62–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Martinez-Selles M, Garcia-Fernandez MA, Moreno M, Bermejo J, Delcan JL. Echocardiographic features of left atrial dissection. Eur J Echocardiogr 2000;1(2):147–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Maeda K, Yamashita C, Shida T, Okada M, Nakamura K. Successful surgical treatment of dissecting left atrial aneurysm after mitral valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg 1985;39(4): 382–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Li Mandri G, Schwartz A, Rose EA, Patel MB, Santiago DW, Di Tullio MR, Homma S. Atrial septal dissection after mitral valve replacement demonstrated by transesophageal echocardiography. Am Heart J 1994;127(1):219–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Sekino Y, Sadahiro M, Tabayashi K. Successful surgical repair of left atrial dissection after mitral valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg 1996;61(5):1528–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Osawa H, Yoshii S, Hosaka S, Suzuki S, Abraham SJ, Tada Y. Left atrial dissection after aortic valve replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003;126(2):604–5. [DOI] [PubMed]