Abstract

Recent studies have revealed that bacteria target stem cells for long-term survival in a Drosophila model. However, in mammalian models, little is known about bacterial infection and intestinal stem cells. Our study aims at understanding bacterial regulation of the intestinal stem cell in a Salmonella colitis mouse model. We found that Salmonella activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway that is known to regulate stem cells. We identified Salmonella protein AvrA that modulates Wnt signaling including upregulating Wnt expression, modifying β-catenin, increasing total β-catenin expression, and activating Wnt/β-catenin transcriptional activity in the intestinal epithelial cells. The numbers of stem cells and proliferative cells increased in the intestine infected with Salmonella expressing AvrA. Our study provides insights into bacterial infection and stem cell maintenance.

Keywords: Stem cell, Wnt, β-catenin, Salmonella, AvrA, Proliferation, type three secretion system, bacterial effector

Introduction

Enteric bacteria manipulate the pathways critical for the immune response and host defenses. Recently, studies in Drosophila demonstrate that gut homeostasis is maintained through a balance between cell damage due to the collateral effects of bacteria killing and epithelial repair by stem cell division [1,2,25]. Global gene expression analysis of Drosophila intestinal tissue with bacterium Erwinia carotovora infection revealed that immune responses in the gut are regulated by the Imd and JAK-STAT pathways. The ingestion of bacteria had a dramatic impact on the physiology of the gut, including the modulation of stress response and increased stem cell proliferation and epithelial renewal [1,2,25]. Although the Drosophila gut provides a powerful model to study the integration of stress and immunity with pathways associated with stem cell control, little is known in the mammalian models of bacterial infection and intestinal stem cells. Due to the complexity of the intestinal gut flora, the identification of the specific microbial agents that contribute to stem cell signaling remains challenging.

In the mammalian intestine, crypts and villi form the fundamental repetitive unit of the tissue. The crypt is a proliferative compartment which is composed of 250–300 cells that are in constant active proliferation; it also generates all of the cells required to renew the entire intestinal epithelium in mice in 2–3 days. Therefore, the intestine is one of the best models for studying adult stem cells in vivo [3]. Stem cells in the intestine are regulated by Wnt signaling. The Wnt gene family consists of 19 members in mammals. These family members are implicated in the regulation of a wide variety of normal and pathological processes, including embryogenesis, differentiation, and carcinogenesis [4,5]. The canonical Wnt pathway regulates the upstream portion of the β-catenin pathway [6,7]. Without Wnt, β-catenin is constitutively degraded. When Wnt ligands are bound to the Frizzled/LRP co-receptor complex, β-catenin is stabilized and activated. Beta-catenin translocates to the nucleus, where it binds Tcf transcription factors, thus activating Wnt target genes [8,9].

AvrA is a newly described bacterial effector present in 80% of Salmonella enterica serovar [10,11] and E. coli [12]. It is transferred into host cells through the type three secretion system, a bacterial needle-like apparatus [10]. AvrA regulates β-catenin ubiquitination and stabilizes β-catenin [13–17], a key regulator of intestinal epithelial proliferation. Previously, we demonstrated that bacteria activate the β-catenin pathway [14,16]. Because β-catenin is at the downstream end of the Wnt pathway, we reason that pathogenic Salmonella modulate the intestinal stem cells and that AvrA activates stem cell niches through the Wnt pathway. In present study, we found that Salmonella infection activates signaling pathways related to stem cells in vivo. We have also found that AvrA may contribute to the stem cell maintenance in Salmonella-infected mice. AvrA activates Wnt signaling at multiple levels, including upregulating Wnt mRNA expression, increasing total β-catenin expression, and activating Wnt/β-catenin transcriptional activity in the intestinal epithelial cells. The number of stem cells and proliferative cells increased in the intestine infected with Salmonella expressing AvrA. Our results provide insights into bacterial infection and intestinal stem cell niches.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Bacterial strains include S. typhimurium 1344, SB1117 [10], S. typhimurium mutants PhoPc, PhoPc AvrA− and PhoPc AvrA−/AvrA+[15]. Bacterial growth conditions were as follows: non-agitated microaerophilic bacterial cultures were prepared by inoculating 10 ml of Luria-Bertani broth with 0.01 ml of a stationary phase culture, followed by overnight incubation (~18 h) at 37°C, as previously described [18].

Streptomycin pre-treated mouse model

Animal experiments were performed using specific-pathogen-free female C57BL/6 mice (Taconic, Hudson, NY) that were 6–7 weeks old. The protocol was approved by the University of Rochester University Committee on Animal Resources. Water and food were withdrawn 4 h before oral gavage with 7.5 mg of streptomycin per mouse. Mice were infected with 1×107 CFU of S. typhimurium (100 μl suspension in HBSS) or treated with sterile HBSS (control) by oral gavage as previously described [15,17]. At 6 or 18 h, or 4 days after infection, mice were sacrificed and tissue samples from the intestinal tracts were removed for analysis.

Immunoblotting

Mouse epithelial cells were scraped and lysed in lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA (pH 8.0), 0.2 mM sodium ortho-vanadate, protease inhibitor cocktail), and the protein concentration was measured. Equal amounts of proteins were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with antibodies as previously described [15,17].

Real-time quantitative PCR analysis

Total mRNA was extracted from scraped mouse colonic epithelial cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and reverse transcribed using the SuperScript™ III first-strand synthesis kit (Invitrogen). cDNA was then subjected to real-time PCR (SYBR Green PCR kit, BioRad) with primers (Table 1). Percent expression was calculated as the ratio of the normalized value of each sample relative to that of the corresponding untreated control cells. All real-time PCR reactions were performed in triplicate.

Table 1.

Primers for real-time PCR

| Name | Sequences of primers | Length of PCR (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| Wnt3 Fw | 5- GTC TGC TAA TGC TGG CTT GAC -3 | 146 |

| Wnt3 Rv | 5- TAG GAA GGG ATG GGA GGT GT- 3 | |

| Wnt6 Fw | 5- TTT ACA CCA GCC CAC GAA AG- 3 | 162 |

| Wnt6 Rv | 5- ACT CAC CCA TCC ATC CCA GTA -3 | |

| Wnt9a Fw | 5- ATG GTG TGT CTG GCT CCT G-3 | 132 |

| Wnt9a Rv | 5- CAG TGG CTT CAT TGG TAG TGC T-3 | |

| TCF-4 Fw | 5-GGACGGACAAAGAGCTGAGTG -3 | 208 |

| TCF-4 Rv | 5- ATGTGGTCATAGGGAGTCCCA -3 | |

| Actin Fw | 5-TGTTACCAACTGGGACGACA-3 | 139 |

| Actin Rv | 5- CTGGGTCATCTTTTCACGGT-3 |

Wnt transcriptional activity assay

The activity of the Wnt/β-catenin signal transduction pathway was measured using the Cignal TCF/LEF Reporter Assay (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD). Briefly, human intestinal cancer cell line HCT1116 was co-transfected with an inducible TCF/LEF-responsive firefly luciferase reporter or a non-inducible firefly luciferase reporter as a negative control, as well as specific pCMV-AvrA or pCMV. LiCl treatment (30 nM for 24 h after transfection) was used as the positive control. Luciferase activity was monitored using the dual luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI). Experiments were done in triplicate with three repeats.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were fixed and processed the next day by standard techniques, as previously described [15]. The number of proliferating cells was detected by immunoperoxidase staining for the thymidine analog, bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU). Animals were injected with 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (100 mg/kg; Sigma, St. Louise, MO, USA), i.p., 2 h before sacrifice. Specimens were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and handled as previously described [15]. The slides were stained with anti- BrdU, anti-Bmi 1 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), or anti-p-β-catenin (ser 552) (Cell Signal, Beverly, MA) antibodies.

Immunofluorescence

Intestinal tissues were freshly isolated and embedded in paraffin wax after fixation with 10% neutral buffered formalin. Tissue samples or cultured cells were processed for immunofluorescence as described previously [17]. The slides were stained with anti-Lgr5 (Abcam), anti-Jagged1, anti-Salmonella lipopolysaccharide (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) antibodies. Cells or tissues were mounted with SlowFade (SlowFade® AntiFade Kit, Molecular Probes) followed by a coverslip, and the edges were sealed to prevent drying. Specimens were examined with a Leica SP5 Laser Scanning confocal microscope.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD. Differences were analyzed by the Student’s t-test. P-Values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

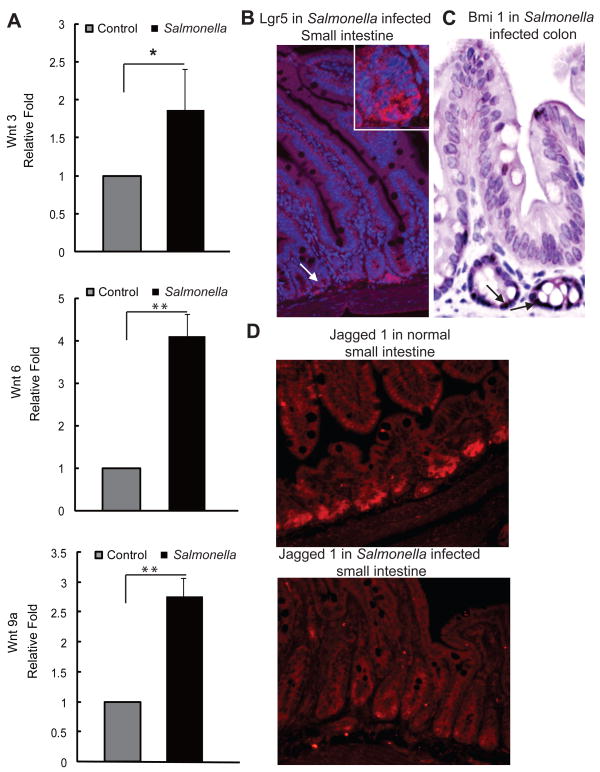

Bacterial infection alters Wnt expression and stem cell markers

Wnt3, Wnt6, and Wnt9A are known to regulate intestinal stem cells [5]. Using a Salmonella colitis mouse model, we assessed Wnt mRNA expression before and after Salmonella infection. The mRNA levels of Wnt3, 6, and 9a were significantly upregulated in the intestinal epithelial cells by Salmonella (Fig. 1A). Our immunostaining data of Igr5, an intestinal stem cell marker, showed the location of the stem cells at the base of the crypts in Salmonella-infected mouse intestines (Fig. 1B). We also detected the location of the stem cell marker, Bmi1, which was induced by Salmonella (Fig. 1C). Moreover, Wnt and Notch pathways work together [5] and Jagged 1 is a link is between Wnt and Notch pathways involved in cell-fate decisions [19,20]. We found that the majority of Jagged 1 located at the bottom of the crypts of the small intestine. However, after Salmonella infection, Jagged 1 was found to be translocated and diffusely distributed in the crypts (Fig. 1D). Taken together, these data indicate that Salmonella infection induces a dynamic change in the stem cells.

Figure 1.

Salmonella infection involves Wnt signaling and stem cells. (A) Wnt3, Wnt6, and Wnt 9A mRNA expression in intestinal epithelial cells post-Salmonella infection. *P<0.05; **P< 0.01. (B–C) Lgr5 and Bmi1 localization in the Salmonella infected intestine. (D) Relocation of Jagged 1 in the mouse intestine 4 days post-Salmonella infection.

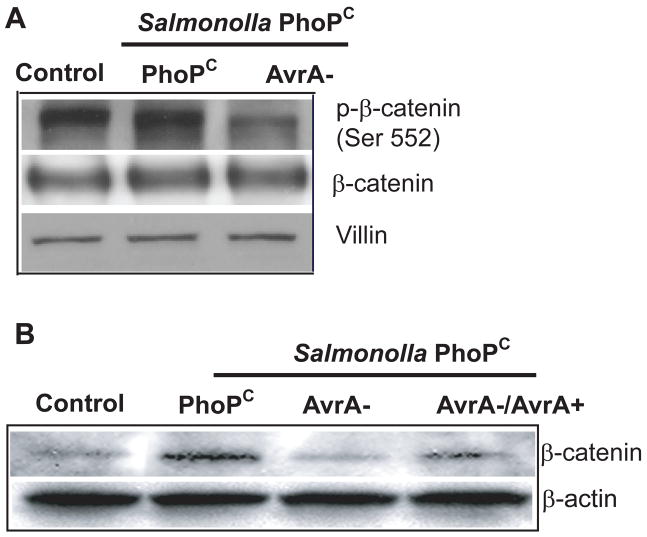

Salmonella AvrA modulates phosphorylated-β-catenin and increases total β-catenin expression

Previous studies have demonstrated that Salmonella AvrA stabilizes β-catenin [13–17]. Because β-catenin is at the downstream end of the Wnt pathway, we reasoned that AvrA activates stem cell niches through the Wnt pathway. Phosphorylated-β-catenin (ser 552) is another stem cell marker [21], so we tested whether AvrA changes phosphorylated-β-catenin expression. We found that phosphorylated-β-catenin (ser 552) is decreased by infection with an AvrA-deficient bacterial strain (AvrA−), but not by bacterial strains expressing AvrA in vivo (Fig. 2A PhoPc and AvrA+/−). We also assessed the total amount of β-catenin present in mice after infection. Salmonella PhoPc with AvrA expression increased the total amount of β-catenin. Total β-catenin was decreased in the presence of PhoPc AvrA− (lacking AvrA expression) bacteria, whereas β-catenin was stabilized in the presence of PhoPc AvrA−/AvrA+ bacteria (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Bacterial protein, AvrA, regulates β-catenin protein expression in intestinal cells in vivo. Mice were infected with S. typhimurium PhoPC, PhoPC/AvrA− (AvrA gene mutant), or PhoPC/AvrA−/AvrA+ (AvrA gene restored). Colonic epithelial cells were scraped, and total cell lysates were analyzed for phosphorylated-β-catenin (ser552) levels by immunoblotting. (A) AvrA modulated the stem cell marker phosphorylated-β-catenin (ser 552) expression in intestinal epithelial cells. Villin is an epithelial cell marker. (B) AvrA in Salmonella increased the total β-catenin expression in intestinal epithelial cells.

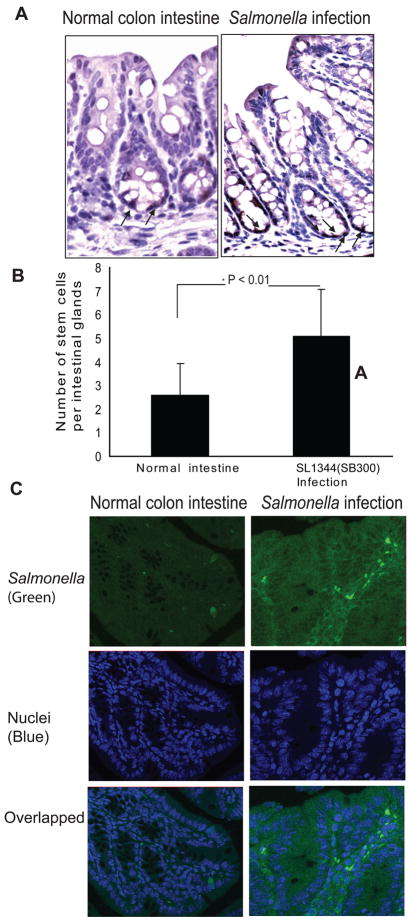

Location of phosphorylated-β-catenin (ser 552) in the Salmonella infected intestine

We also investigated the location of p-β-catenin (ser 552) in the normal and Salmonella-infected intestine (Fig. 3A). The p-β-catenin (ser 552) was located in the nuclei of cells located at the bottom of crypts, i.e., the stem cell niches. We also tested whether infection with the Salmonella strain with AvrA expression changes the number of phosphorylated-β-catenin positive staining cells. Our data showed that the number of cells with positive p-β-catenin (ser552) staining significantly increased in the Salmonella-infected intestine compared to that in the normal intestine without any bacterial treatment (Fig. 3B). A concern for the in vivo study is the bacterial colonization ability in the intestinal epithelial cells. To address the location by which S. typhimurium infects the intestine, we stained infected colon tissues for Salmonella lipopolysaccharide by immunofluorescence. S typhimurium bacteria were found in the intestine 4 days post infection (Fig. 3C). This localization indicates the persistence of Salmonella infection in mouse intestine.

Figure 3.

Location of phosphorylated -β-catenin (ser552) in the Salmonella-infected mouse intestine. (A) Immunohistochemical staining of phosphorylated-β-catenin in the Salmonella-infected intestine. (B) Numbers of phosphorylated-β-catenin (ser552) positively stained cells in the normal and Salmonella-infected intestines. (C) Distribution of Salmonella (green) in mouse colon 4 days post infection.

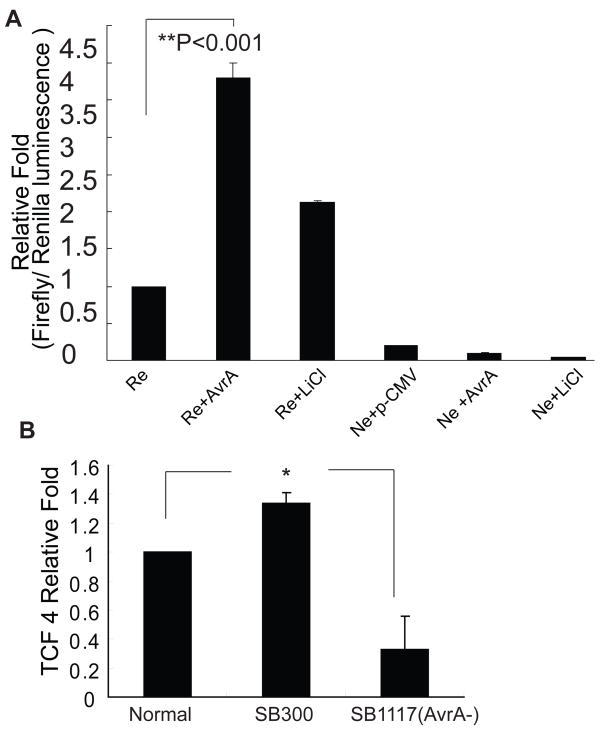

AvrA expression activates the Wnt pathway

We further investigated Wnt/β-catenin transcriptional activity in activity in a human intestinal cancer cell line HCT1116 colonized by Salmonella. We found that bacterial protein AvrA was able to significantly increase the Wnt/β-catenin transcriptional activity (Fig. 4A). LiCl treatment, which activates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, was used as a positive control. Upon Wnt activation, β-catenin became stabilized and translocated to the nuclei binding with T cell factors (TCF). In addition, Salmonella colonization of the HCT1116 cells increased TCF 4 at the mRNA level (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that AvrA activates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, thus regulating intestinal stem cells.

Figure 4.

Salmonella AvrA expression activates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. (A) AvrA transfection of human intestinal cancer HCT116 cells activated a TCF/LEF-responsive reporter (Re). Ne: negative control. The Luc activity was normalized to the internal control (Rluc activity). (B) Salmonella colonization increased TCF4 mRNA expression in intestine.

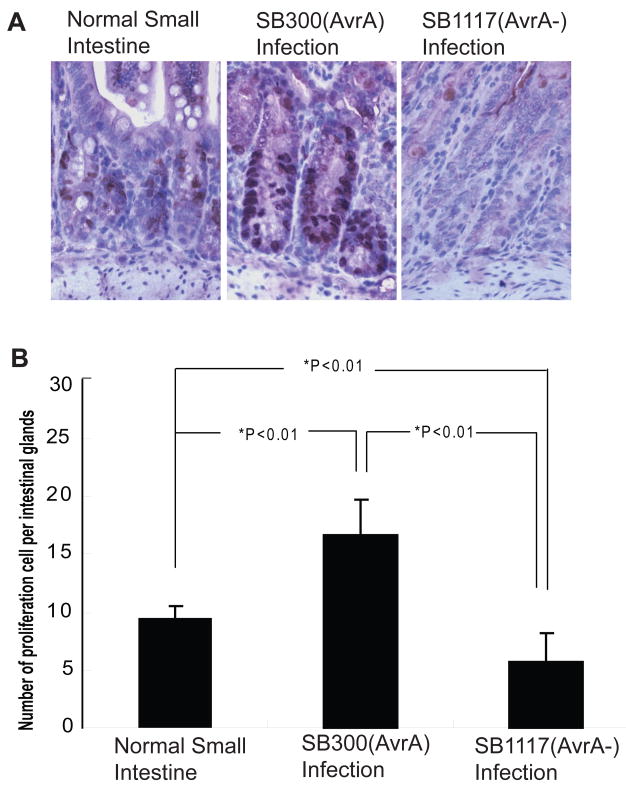

AvrA increases small intestinal epithelial cell proliferation in vivo

While examining changes in stem cell marker expression induced by bacterial colonization, we also examined the effect of AvrA on intestinal epithelial cell proliferation, which is regulated by the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. BrdU staining was performed to measure BrdU incorporation into newly synthesized DNA. BrdU-positive staining (brown) showed that Salmonella SB117 (AvrA−) induced a dramatic decrease in epithelial cell proliferation (Fig. 5), whereas the strain SL1344 (SB300) with AvrA expression significantly increased cell proliferation (Fig. 5). Please note that the proliferating cells are located at the bottom of the small intestinal crypts (identified by a pathologist). The number of proliferating cells per intestinal gland further demonstrated that AvrA increased intestinal epithelial cell proliferation in vivo (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Salmonella AvrA expression increases small intestinal epithelial cell proliferation in vivo. (A) BrdU labeling of small intestine epithelial cells at 4 days post-Salmonella infection. (B) Proliferation index in intestinal epithelial cells. The number of BrdU-positive cells per three high powered fields was counted. n=3 in each experimental group.

Discussion

In the present study, we report that enteric Salmonella infection modulates intestinal stem cells and that Salmonella protein AvrA activates stem cell niches through the Wnt pathway. AvrA increases Wnt expression, β-catenin modification, total β-catenin expression, transcriptional activity, and stem cell markers in the intestinal epithelial cells. There was less epithelial cell proliferation in cells infected by AvrA− Salmonella and greater cell proliferation in colons infected by Salmonella with sufficient AvrA expression. Whereas intestinal stem cells have been intensively studied, the role of bacteria in modulating intestinal stem cell signaling has not been well established. Our findings provide important insights into how a bacterial protein contributes to the activation of the Wnt pathway and the maintenance of intestinal stem cells.

Currently, most stem cells studies use knock-in or transgenic models. The estimated number of pluripotent stem cells is about 30 cells/crypt [3]. We understand the challenge of working on normal mice. The modification of stem cell numbers and distribution requires close monitoring at different time points post-infection. We used multiple stem cell markers and assays to identify the stem cells and study their locations, number, and proliferation capacity and how those properties were affected by Salmonella. We found that AvrA contributes to the upregulation of the stem cell marker, p-β-catenin (ser 552). However, Lgr5 protein expression did not change during the early stage of Salmonella infection (8 h post-infection). In contrast, at 4 days post-infection, there was a significant reduction of Lgr5 protein expression in the Salmonella-infected small intestine (data not shown). These results indicate that Salmonella infection dynamic changes the number of the stem cells during the different stages of infection. Previous studies [14,15] and our current results demonstrate that AvrA increases intestinal epithelial cell proliferation. Whereas bacterial infection induces the epithelial loss, AvrA constitutes to maintenance of the intestinal epithelia. Further investigation is needed to clarify AvrA’s role on the stem cell renewal, differentiation, and proliferation.

Activation of β-catenin pathway initiates the neoplastic process, resulting in intestinal adenomas. These tumors progress as mutations in genes, such as p53, accumulate [22]. P53 plays role in both cancer and stem cell growth [23]. Our unpublished data showed that p53 pathway is activated by Salmonella infection in vivo. AvrA is a multi-functional protein that influences eukaryotic cell pathways that utilize phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and acetylation [12,15,24]. Assessing other pathways, such as the JNK, JAK-STAT, and p53 pathways, will further elucidate the role of AvrA on stem cells in tumor progression.

In summary, we find that pathogenic Salmonella infection modulates intestinal stem cells and the Salmonella protein, AvrA, activates stem cell niches through the Wnt pathway. Our long-range goal is to elucidate the role of enteric bacteria in the development of colitis and cancer through their modulation of intestinal stem cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIHDK075386 and American Cancer Society RSG-09-075-01-MBC to J.S.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cronin SJ, et al. Genome-wide RNAi screen identifies genes involved in intestinal pathogenic bacterial infection. Science. 2009;325:340–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1173164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pitsouli C, Apidianakis Y, Perrimon N. Homeostasis in infected epithelia: stem cells take the lead. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6:301–7. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Flier LG, Clevers H. Stem cells, self-renewal, and differentiation in the intestinal epithelium. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:241–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katoh M. WNT signaling pathway and stem cell signaling network. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4042–5. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katoh M. Networking of WNT, FGF, Notch, BMP, and Hedgehog signaling pathways during carcinogenesis. Stem Cell Rev. 2007;3:30–8. doi: 10.1007/s12015-007-0006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haegebarth A, Clevers H. Wnt signaling, lgr5, and stem cells in the intestine and skin. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:715–21. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He TC, et al. Identification of c-MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science. 1998;281:1509–12. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato T, et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459:262–5. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reya T, Clevers H. Wnt signalling in stem cells and cancer. Nature. 2005;434:843–50. doi: 10.1038/nature03319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardt WD, Galan JE. A secreted Salmonella protein with homology to an avirulence determinant of plant pathogenic bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9887–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Streckel W, Wolff AC, Prager R, Tietze E, Tschape H. Expression profiles of effector proteins SopB, SopD1, SopE1, and AvrA differ with systemic, enteric, and epidemic strains of Salmonella enterica. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2004;48:496–503. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200400035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du F, Galan JE. Selective inhibition of type III secretion activated signaling by the Salmonella effector AvrA. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000595. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun J, Hobert ME, Duan Y, Rao AS, He TC, Chang EB, Madara JL. Crosstalk between NF-kappaB and beta-catenin pathways in bacterial-colonized intestinal epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G129–37. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00515.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun J, Hobert ME, Rao AS, Neish AS, Madara JL. Bacterial activation of beta-catenin signaling in human epithelia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G220–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00498.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye Z, Petrof EO, Boone D, Claud EC, Sun J. Salmonella effector AvrA regulation of colonic epithelial cell inflammation by deubiquitination. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:882–92. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duan Y, Liao AP, Kuppireddi S, Ye Z, Ciancio MJ, Sun J. beta-Catenin activity negatively regulates bacteria-induced inflammation. Lab Invest. 2007;87:613–24. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liao AP, Petrof EO, Kuppireddi S, Zhao Y, Xia Y, Claud EC, Sun J. Salmonella type III effector AvrA stabilizes cell tight junctions to inhibit inflammation in intestinal epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2369. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCormick BA, Colgan SP, Delp-Archer C, Miller SI, Madara JL. Salmonella typhimurium attachment to human intestinal epithelial monolayers: transcellular signalling to subepithelial neutrophils. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:895–907. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.4.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reedijk M, et al. Activation of Notch signaling in human colon adenocarcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2008;33:1223–9. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodilla V, et al. Jagged1 is the pathological link between Wnt and Notch pathways in colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6315–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813221106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He XC, et al. PTEN-deficient intestinal stem cells initiate intestinal polyposis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:189–98. doi: 10.1038/ng1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. p53 function and dysfunction. Cell. 1992;70:523–6. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90421-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong H, Takahashi K, Ichisaka T, Aoi T, Kanagawa O, Nakagawa M, Okita K, Yamanaka S. Suppression of induced pluripotent stem cell generation by the p53–p21 pathway. Nature. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nature08235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones RM, Wu H, Wentworth C, Luo L, Collier-Hyams L, Neish AS. Salmonella AvrA Coordinates Suppression of Host Immune and Apoptotic Defenses via JNK Pathway Blockade. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:233–44. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buchon N, Broderick NA, Poidevin M, Pradervand S, Lemaitre B. Drosophila intestinal response to bacterial infection: activation of host defense and stem cell proliferation. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:200–11. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]