Abstract

This study explored the relationship between multidimensional acculturation attitudes and depressive symptoms in 78 Korean American adults. Approximately 30% of Korean Americans reported scores higher than 16 on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale, indicating the presence of elevated depressive symptoms. In multiple regressions controlling for family income, integration was negatively related to depressive symptoms, whereas marginalization was positively linked to depressive symptoms. Findings can be used in developing an intervention program that targets increasing integration, decreasing marginalization, and therefore decreasing depressive symptoms of Korean Americans.

Keywords: multidimensional acculturation attitudes, depressive symptoms, Korean American

Growing evidence of mental health disparities indicates a elevated level of depressive symptoms in the Korean American population as compared to other ethnic minorities (Huang, Wong, Ronzio, & Yu, 2007; Kuo, 1984; Min, Moon, & Lubben, 2005; Shin, 2002; Yeh & Inose, 2002). An increasing number of studies also indicates acculturation as a critical factor related to elevated depressive symptoms in this population (Kim & Rew, 1994; Oh, Koeske, & Sales, 2002). Acculturation is defined as cultural and psychological changes resulting from the contact of two or more cultural groups and their individual members (Berry, 2006). However, most previous studies conceptualized acculturation as a linear progression of adopting American culture, ignoring the influence of heritage culture.

In reality not all immigrants prefer to adopt American culture or ignore heritage culture in the same way; great variations exist in their attitudes. This individual’s preference about how to acculturate is called acculturation attitudes, which includes four different dimensions that are linked to mental health of immigrants (Berry, 2005, 2006; Matsudaira, 2006). This conceptualization of multidimensional acculturation attitudes may offer helpful information in identifying individuals who may be at high risk for elevated levels of depressive symptoms in Korean Americans. The goal of this study was to examine the relationship between multidimensional acculturation attitudes and depressive symptoms in 78 Korean American adults.

Theoretical Framework

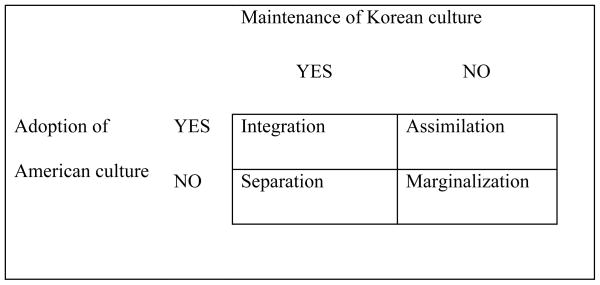

The multidimensional acculturation framework (Berry, 2006) was applied in this study. According to Berry, two fundamental issues in acculturation are (a) immigrants’ maintenance of their heritage culture and (b) immigrants’ adoption of mainstream culture. Based on immigrants’ responses to these matters, Berry describes four acculturation attitudes: integration, marginalization, separation, and assimilation (see Figure 1). For example, Korean Americans may maintain Korean culture and identity while actively participating in American society (i.e., integration). They may exclusively maintain Korean culture and identity while not adopting American culture (i.e., separation) or fully accept American culture while relinquishing Korean culture (i.e., assimilation). Finally, marginalization occurs when Korean Americans are out of cultural and psychological contact with both Korean culture and American society.

Figure 1.

Multidimensional acculturation (Berry, 2006)

In the multidimensional acculturation framework, each immigrant has four acculturation attitudes; depending on circumstances, individuals may have different attitudes (Berry, 1997, 2006; Berry, Kim, Minde, & Mok, 1987). This framework has been used mainly to identify better or worse attitudes for dealing with stress coming from acculturation process and their relationships to immigrants’ health (Matsudaira, 2006). The most adaptive attitude is integration, which is characterized by the ability to balance two cultures; whereas, the least adaptive attitude is marginalization, which is characterized by the experience of psychological anxiety and conflict (Berry, 2006; Kim, Gonzales, Stroh, & Wang, 2006; Park, 1928).

Depressive Symptoms in Korean Americans

When immigrants come to the United States they face changes in many aspects of life. In coping with these changes, immigrants experience a high level of psychological distress including depression (Oh, Koeske, & Sales, 2002). Depression is one of the most common mental health problems, characterized by depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure, feeling of guilt or low self-worth, altered sleep or appetite, low energy levels, and lack of concentration (DSM-IV-TR, 2000; Levenson, 2000). In this paper, the term depressive symptoms is used rather than depression because the condition was assessed using screening tools (e.g., Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, CES-D≥ 16) rather than diagnostic criteria (i.e., DSM-IV-TR).

Several studies found a higher level of depressive symptoms and lower utilization of mental health services in the Korean American populations (Huang, Wong, Ronzio, & Yu, 2007; Kuo, 1984; J. Shin, 2002; Yeh & Inose, 2002). In a study conducted with Asian American elderly in 1980’, Korean Americans (14.37 ± 7.84) scored highest on CES-D and about twice greater than Filipino Americans (9.72 ± 7.12), Japanese Americans (7.30 ± 8.43), and Chinese Americans (6.93 ± 6.82) (Kuo, 1984). In a recent study, the mean score of Korean American elderly (M = 11.9 ~12.9) was lower than the one from Kuo’s (1984) study, but, it was significantly higher than the mean of non-Hispanic White America elderly (M = 7.1 ~ 7.6) (Min, Moon, & Lubben, 2005).

In some studies Korean Americans scored even higher (up to 17.87) in CES-D (Choi, 1997; Kim & Rew, 1994; Shin, 1993). These mean scores in Korean Americans were notably higher than the score of nationwide sample of Koreans in Korea (10.57, no SD given in the paper) (Cho, Nam, & Suh, 1998), general Americans (7.94 ± 7.53 to 9.25 ± 8.58) (Radloff, 1977), and general European Americans (8.9 ± 6.7 to 9.6± 7.5) (Henderson et al., 2005). In a national study with mothers of young children (6~ 22 months old) in the Untied States, more Korean American mothers (44.4%) experienced elevated depressive symptoms than non-Hispanic White mothers (38.5%) (Huang, Wong, Ronzio, & Yu, 2007). Oh and colleagues (2002) examined depressive symptoms in general Korean American adults (mean ages 37) and found that 40% of study participants scored higher in depressive symptoms (M =14.76 ± 9.71).

Acculturation and Depressive Symptoms

Factors related to Korean Americans’ depressive symptoms were old age, being women, low educational attainment, low self-esteem (Shin, 1993), low quality of life, shorter length of residence in the United States (Kim & Rew, 1994), low family income, nonprofessional occupation, low life satisfaction (Koh, 1998), lack of social support, high acculturation stress (Choi, 1997), and low acculturation (Oh et al., 2002). Especially, acculturation was identified as a critical factor related to depressive symptoms in Korean Americans (Choi, 1997; Kim, Han, Shin, Kim, & Lee, 2005; Kim & Rew, 1994; Lee, Crittenden, & Yu, 1996; Oh et al, 2002). Korean Americans who did not keep Korean identity, traditions, and values scored higher in depressive symptoms (Oh et al., 2002). At the same time, those who were more fluent in English and had more interaction with Americans scored lower in acculturation stress, in turn, lower depressive symptoms (Oh et al., 2002).

However, the absence of a widely accepted conceptualization of acculturation and a standardized instrument among Korean Americans caused the lack of proper assessment of acculturation. Some studies examined only a few selected items, such as length of residence in the United States, English proficiency, or cultural activity orientation (Jang et al., 2005; Kim et al.., 2005; Lee et al., 1996). Other studies conceptualized acculturation as adaptation to the mainstream culture which resulted in ignoring immigrants’ desire to maintain own culture (i.e., unidimensional acculturation) (Christine, 2003).

Consequently, there is no study available considering Korean immigrants’ attitudes towards both mainstream and heritage cultures (i.e., multidimensional acculturation). Previous studies considering other ethnic minorities suggested that the multidimensional acculturation approach is more comprehensive than unidimensional view in explaining immigrants’ adjustment (Abe-Kim, Okazaki, & Goto, 2001; Ryder, Alden, & Paulhus, 2000). In a study with Korean Canadians, integration and assimilation were related to better mental health, whereas separation and marginalization were related to poorer mental health (Kim, 1988). However, the relationship between four acculturation attitudes and depressive symptoms in Korean Americans is not known.

Methods

Design and Sample

This study used a correlational study design. The sample consisted of a convenience sample of 78 Korean American adults (49 women and 29 men) living in the Pacific Northwest. With the sample size of 78, there was 81% of power to detect true correlation of .31 between multidimensional acculturation and depressive symptoms. Korean Americans in this study were defined as persons born in Korea of Korean mothers and fathers, residing in the United States at the time of the study and were either American citizen or permanent resident. Even though Korean permanent residents were not technically Korean Americans, in general, psychologists include them under the term “Korean American” in their research because of the limitation on the numbers of accessible participants (Uba, 1994).

Instrumentation

Multidimensional acculturation attitudes

Multidimensional acculturation attitudes were measured using the Acculturation Attitudes Scale (AAS, Kim, 1988). The AAS is a 56-item instrument that assesses 14 areas of individual and family life with four statements representing each acculturation attitude included under each area. The fourteen areas are friendship, marriage, Korean town, child-rearing, furniture, language, ethnic-identity, teaching values and customs to children, TV station, learning history, newspaper, success, naming children, and interests.

Sample questions include: ‘Living in America as a Korean, I would want to know how to speak both Korean and English’ (i.e., integration); ‘I often feel helpless because I can’t seem to express my feelings and thoughts into words’ (i.e., marginalization); ‘To maintain our Korean heritage in America, we must concentrate our efforts in maintaining and teaching Korean language rather than English’ (i.e., separation); and ‘Because we live in America, we do not need to know Korean language. We should focus our attention on speaking English fluently’ (i.e., assimilation).

Respondents responded to the AAS on a 5-point Likert-type scale from “strongly disagree (1)” to “strongly agree (5).” Mean scores range from 1–5; higher scores indicate greater preference for each acculturation attitude. This scale was developed in English and Korean simultaneously to study Korean Canadians (Kim, 1988). Therefore, wording of ‘Canadian’ in this measure was changed to ‘American’ to fit Korean Americans. Kim (1988) established construct, concurrent, and convergent validity of the measure. The Cronbach alpha for the Korean version of the current study sample was .84 for Integration, .72 for Marginalization, .77 for Separation, and .84 for Assimilation.

Depressive symptoms

The CES-D (Radloff, 1977), which was developed for the general community population, was used to assess Korean American depressive symptoms in this study. The CES-D consists of 20 items that assess negative affect (i.e. blues, depressed, lonely, cry, sad), positive affect (i.e. good, hopeful, happy, enjoy), somatic and retarded activity (i.e. poor appetite, restless sleep), and interpersonal difficulty (i.e. perceived unfriendliness and dislike). It utilizes a 4-point Likert-type scale from “rarely (0)” to “almost or all of the time, 5–7 days/week (3).” Scores range from 0 to 60 with a higher score indicating a higher level of depressive symptoms. A score of 16 or higher is considered “positive” for elevated depressive symptoms (Radloff). The Korean version of the CES-D has shown satisfactory reliability and content, construct, and concurrent validity (Kim, Han, & Phillips, 2003; Noh, Avison, & Kasper, 1992; Oh et al., 2002). The Cronbach alpha for the Korean version in the current study was .86.

Procedure

The author visited Korean American organizations such as churches and Korean language schools in the Pacific Northwest to explain the study and to distribute the instruments. The instruments included both Korean and English versions so participants could use their preferred language. All of the participants used the Korean version except two participants who came to the Untied States as young children. Participants completed the instruments at home and then mailed them to the author using self-addressed stamped envelopes. The author’s Institutional Human Subjects Review Committee approved the study and informed written consent was obtained from each subject before participation.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations, ranges, and distributions were calculated. A one way ANOVA was done to examine differences between men and women, and Pearson correlations and multiple regression were used for the aggregate sample. The dependent variable was depressive symptoms and independent variables were integration, marginalization, separation, and assimilation.

Results

The mean age of the participants was 43.68 (SD = 4.25, range 34~57) years, and they had lived in the United States for an average of 17.05 (SD = 8.42, range 2~4) years. They received an average of 14.92 years (SD = 2.58, range 6~22) of education. All of them were born in Korea; American citizens (n= 44, 56%) and permanent residents (n=34, 44%) were included. In terms of their ethnic identity, 71% (n=55) considered themselves Korean, followed by 27% (n=21) Korean American, and 3% (n=2) missing. None perceived themselves as American. Their religion was 71% (n = 55) Protestant, 23% (n=18) Catholic, 3% (n = 2) no religion, and 4% (n = 3) missing. Ninety-five percent (n=74) were married, 3% remarried (n = 2), 1% divorced (n = 1), and 1% widowed (n=1). Nineteen percent families have annual family income lower than $40,000, whereas 38.2% has between $40,001 and $80,000, and 43.6% has income over $80,001.

Korean American men (M = 11.34, SD = 7.78) and women (M = 12.29, SD = 7.83) had similar levels of depressive symptoms, F(1, 76) = .68, p = ns. The proportion of respondents who scored 16 or higher on the CES-D (men 28.6%, women 31%) was also similar. Therefore, the data were combined as a total sample. The mean CES-D score of this study sample was 12.29 (SD = 7.83). Thirty percent of Korean Americans experienced elevated depressive symptoms. In terms of acculturation attitudes, Korean Americans preferred integration (4.07± .54), followed by marginalization (2.46± .45), separation (2.23± .42), and assimilation (2.11± .47). Table 1 also shows correlations among all study variables, including income, the only demographic variable related to CES-D (r = −.23, p < .01). In further analysis, family income was negatively correlated with marginalization (r = −.38, p < .001) and separation (r = −.31, p < .01).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among study variables (N = 78)

| Income | Integration | Marginalization | Separation | Assimilation | CES-D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | — | |||||

| Integration | .15 | — | ||||

| Marginalization | −.38*** | −.18 | — | |||

| Separation | −.31** | −.16 | .67*** | — | ||

| Assimilation | .09 | −.41*** | .43*** | .31** | — | |

| CES-D | −.23* | −.25* | .47*** | .33** | .13 | — |

Note.

p<.05,

p< .01,

p< .001 (2-tailed).

Upon multiple regressions, as shown in Table 2, family income explained 5% of the variance in depressive symptoms. When multiple regressions were performed to examine the relationship between different acculturation attitudes and depressive symptoms controlling for family income, F change of the equation was significant. The significant factors were integration and marginalization, indicating that the lower integration and the greater marginalization scores, the higher the scores on the CES-D in Korean Americans. The model explained an additional 22% of the variance in depressive symptoms.

Table 2.

Regressions on depressive symptoms (N = 78)

| Variable | B (SE) | β | ΔR2 | ΔF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ||||

| Family income | −1.13 (.52)** | −.23 | .05 | 4.15* |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Family income | .13 (.59) | .03 | .22 | 5.46*** |

| Integration | −3.48 (1.64)* | −.24 | ||

| Marginalization | 8.81 (2.68)** | .50 | ||

| Separation | .48 (2.52 | .03 | ||

| Assimilation | −3.27 (2.20) | −.19 | ||

p< .10,

p<.05,

p< .01,

p< .001 (2-tailed).

Discussion

The mean score on the CES-D in this study was lower than in previous studies. This finding may be related to the difference in study samples that most previous studies examined either Korean American elderly (Kuo, 1984) or women (Kim & Rew, 1994; Shin, 1993), whereas the current study examined general adults, both men and women. Or, it could be related to sampling bias that might have happened in three ways. Considering the sample was recruited from Korean organizations, the sample might have had a greater sense of connectedness with the community which might have had a buffering effect for depressive symptoms. The mean of this study was lower than what Oh and colleagues (2002) found in general Korean American adults (mean ages 37) using a random sampling. In addition, the family income of the study sample indicated that most of the participants were from middle to upper middle classes, which might explain why the prevalence of depressive symptoms in this study sample was lower than previous studies with Korean Americans. Furthermore, depressed immigrants probably were less enthusiastic about participating in the study, which may have led to an overall selection bias in participation. However, the current sample still scored higher than Koreans in Korea (Cho et al., 1998), other Asian Americans (Kuo, 1984), and general European Americans (Henderson et al., 2005), indicating relatively poorer mental health in Korean Americans.

Family income was negatively related to depressive symptoms, which is consistent with previous finding among Korean Americans (Koh, 1998; Oh et al., 2002). Persons with lower family income are likely to encounter more stressful life situations and have fewer resources to deal with the stressors than those who have higher family income, resulting in elevated depressive symptoms. When all four attitudes were entered into the multiple regression equation simultaneously as four independent variables controlling for family income, integration and marginalization were significant predictors of depressive symptoms. This finding is consistent with multidimensional acculturation framework that says integration is the most adaptive while marginalization is least adaptive (Berry, 2006; Matsudaira, 2006). This finding also is consistent with Kim’s (1988) finding among Korean Canadians that integration was related to better mental health, whereas marginalization was related to poorer mental health.

Theoretically, integration occurs when immigrants maintain their own culture while making contact with the new society (Berry, 2006). In previous studies, Korean immigrants in North America who scored higher in integration maintained Korean culture, language, and daily life styles (e.g., food, TV/video, newspaper, friends, organizations) while adopting American culture and languages (Kim & Wolpin, in press; Kim, 1988). Korean Canadians who scored high on integration were more likely to report higher life satisfaction (Kim, 1988). This ability to navigate two cultures enables immigrants to be comfortable and flexible in both social contexts and relationships with others. According to Padilla (2006), integrated immigrants possess qualities and identities that enable them to switch easily from one culture to another as necessary. Consequently, integrated immigrants are well adjusted, open to others, and function as cultural brokers between their own ethic group and other groups (Padilla, 2006). These characteristics might explain negative relationship between integration and depressive symptoms in Korean Americans.

In contrast, the traits of marginalization are quite different from the characteristics of integration. Marginalization happens when immigrants neither maintain Korean cultural background nor adopt American culture. Therefore, immigrants who are high in marginalization tend to be isolated from both heritage and mainstream cultures (Berry, 2006). In previous studies, Korean immigrants in North America who scored high on marginalization tended to be less educated, had less income, had lower English fluency, and adapted less American life styles, and had lower life satisfaction (Kim & Wolpin, in press; Kim, 1988). These kinds of traits of marginalized immigrants are also found in other populations such as Russian-speaking immigrants in Sweden (Blomstedt, Hylander, & Sundquist, 2007).

Without connecting with either heritage or host cultures immigrants tend to become “marginal men,” who have an unstable double conscious mind and who experience instability, restlessness, and malaise due to two conflicting cultures (Del Pilar & Udasco, 2004; Park, 1928; Stonequist, 1935), which may increase depressive symptoms in these immigrants. This finding is consistent with previous research that marginalization was related to depressive symptoms among Korean Americans, Chinese Americans, and Japanese Americans (Kim et al., 2006). This result expands Oh and colleagues (2002) finding that Korean Americans who did not keep Korean identity, traditions, and values scored higher in depressive symptoms. When acculturation was considered as multidimensional rather than unidimensional, elevated depressive symptoms was related to the condition of not maintaining Korean identity while not adopting mainstream culture.

Several limitations and strengths must be noted. First, examining correlations among study variables, four acculturation attitudes were correlated with each other, which is consistent with what Kim (1988) found among Korean Canadians. However, this finding may be counter to the theoretical suggestion that four acculturation attitudes are independent each other (Berry, 2005). This finding may suggest that these theoretically incomparable attitudes may share an underlying latent construct (Matsudaira, 2006). Second, as noted in the discussion section, sampling bias might have happened. Therefore, the result may not be generalized to an overall Korean American population. Finally, the Korean Americans may have elevated depressive symptoms due to reasons other than acculturation. Previous studies found other factors related to Korean Americans’ depressive symptoms such as low quality of life (Kim & Rew, 1994), lack of social support, and high acculturation stress (Choi, 1997). The strength of the study was using multidimensional acculturation framework that suggests that acculturation attitudes are related to mental health of immigrants (Matsudaira, 2006). The framework was practical and useful in identifying individuals who may be at high risk for elevated levels of depressive symptoms.

Conclusion

The result of this study indicates that integration was negatively related to depressive symptoms, whereas marginalization was positively related to depressive symptoms in Korean Americans. Future research should focus on developing a mental health promotion intervention that incorporates ways of increasing integration while decreasing marginalization, which can be provided through Korean community organizations. A longitudinal study is needed to examine whether or not acculturation attitudes and their relationship to depressive symptoms change over time. Nurses who work with Korean American populations can use the findings by assessing acculturation attitudes, especially marginalization, as a way to estimate risk for depressive symptoms and intervene preventively. The intervention may need to start with helping high risk individuals understand the similarities and differences between the cultures and how to engage with either or both of them. This may decrease Korean Americans’ depressive symptoms.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by RIFP and IESUS from the University of Washington and a career development award, NINR #K01 NR08333.

References

- Abe-Kim J, Okazaki S, Goto S. Unidimensional versus multidimensional approaches to the assessment of acculturation for Asian American populations. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2001;7(3):232–246. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.3.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 1997;46(1):5–68. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2005;29:697–712. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturation: A conceptual overview. In: Bornstein MC, Cote LR, editors. Acculturation and parent-child relationships: Measurement and development. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erbaum Associates, Publishers; 2006. pp. 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Kim U, Minde T, Mok D. Comparative studies of acculturative stress. International Migration Review. 1987;21(3):491–512. [Google Scholar]

- Blomstedt Y, Hylander I, Sundquist J. Self reported integration as a proxy for acculturation. Nursing Research. 2007;56(1):63–69. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200701000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho MJ, Nam JJ, Suh GH. Prevalance of symptoms of depression in a nationwide samples of Korean adults. Psychiatry Research. 1998;81:341–352. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(98)00122-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi G. Acculturative stress, social support, and depression in Korean American families. Journal of Family Social Work. 1997;2(1):81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Christine Y. Age, acculturation, cultural adjustment, and mental health symptoms of Chinese, Korean, and Japanese immigrant youths. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2003;9(1):34–48. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Pilar JA, Udasco JO. Marginality theory: The lack of convergent validity. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2004;26(1):3–15. [Google Scholar]

- DSM-IV-TR. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-IV-TR (Test revision) (Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders) Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson C, Diez Roux AV, Jacobs DR, Jr, Kiefe CI, West D, Willians DR. Neighborhood characteristics, individual level socioeconomic factors, and depressive symptoms in young adults: the CARDIA study. Journal of Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59:322–328. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.018846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZJ, Wong FY, Ronzio CR, Yu SM. Depressive symptomatology and mental health help-seeking patterns of U.S.- and foreign-bron mothers. Maternal Child Health Journal. 2007;11:257–267. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y, Kim G, Chiriboga D. Acculturation and manifestation of depressive symptoms among Korean-American elder adults. Aging & Mental Health. 2005;9:500–507. doi: 10.1080/13607860500193021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Wolpin S. Acculturation and characteristics of Korean American families. The Journal of Cultural Diversity: An Interdisciplinary Journal (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Han H, Phillips L. Metric equivalence assessment in cross-cultural research: using an example of the Center for Epidemiological Studies -- Depression Scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 2003;11(1):5–18. doi: 10.1891/jnum.11.1.5.52061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Han H, Shin H, Kim K, Lee H. Factors associated with depression experience of immigrant populations: A study of Korean immigrants. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2005;19:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Gonzales N, Stroh K, Wang J. Parent-child cultural marginalization and depressive symptoms in Asian American family members. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;34:167–182. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Rew L. Ethnic identity, role integration, quality of life, and depression in Korean-American women. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 1994;8(6):348–356. doi: 10.1016/0883-9417(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim U. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Queen’s University; Kingston, Canada: 1988. Acculturation of Korean immigrants to Canada: Psychological, demographic, and behavioral profiles of emigrating Koreans, non-emigrating Koreans, and Korean-Canadians. [Google Scholar]

- Koh K. Perceived stress, psychopathology, and family support in Korean immigrants and non-immigrants. Yonsei Medical Journal. 1998;39:214–221. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1998.39.3.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo WH. Prevalence of depression among Asian-Americans. Journal of Nervous Mental Disease. 1984;172:449–457. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198408000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MC, Crittenden K, Yu E. Social support and depression among elderly Korean immigrants in the United States. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 1996;42:313–329. doi: 10.2190/2VHH-JLXY-EBVG-Y8JB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenson JM. Depression. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Matsudaira T. Measures of psychological acculturation: A review. Transcultural Psychology. 2006;43(3):462–487. doi: 10.1177/1363461506066989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min JW, Moon A, Lubben JE. Determinants of psychological distress over time among older Korean immigrants and non-Hispanic White elders: Evidence from a two wave panel study. Aging & Mental Health. 2005;9(3):210–222. doi: 10.1080/13607860500090011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, Avison WR, Kasper V. Depressive symptoms among Korean immigrants: Assessment of a translation of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4(1):84–91. [Google Scholar]

- Oh Y, Koeske G, Sales E. Acculturation, stress, and depressive symptoms among Korean immigrants in the United States. Journal of Social Psychology. 2002;142(4):511–516. doi: 10.1080/00224540209603915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla AM. Bicultural social development. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2006;28(4):467–497. [Google Scholar]

- Park R. Human migration and the marginal man. The American Journal of Sociology. 1928;33(6):881–893. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder A, Alden L, Paulhus D. Is acculturation unidimensional or bidimensional? O head-to-head comparison in the prediction of personality, self-identity, and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Studies. 2000;79(1):49–65. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J. Help-seeking behaviors by Korean immigrants for depression. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2002;23:461–476. doi: 10.1080/01612840290052640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin K. Factors predicting depression among Korean-American women in New York. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 1993;30(5):415–423. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(93)90051-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stonequist EV. The problem of the marginal man. The American Journal of Sociology. 1935;1:1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Uba L. Asian Americans: Personality patterns, identity, and mental health. NY: Guilford; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh C, Inose M. Difficulties and coping strategies of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean immigrant students. Adolescence. 2002;37(145):69–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]