Abstract

Human adipose-derived stromal cells (hASCs) were evaluated in vitro for their ability to bind vascular adhesion and extracellular matrix proteins in order to arrest (firmly adhere) under physiological flow conditions. hASCs were flowed through a parallel plate flow chamber containing substrates presenting immobilized Type I Collagen, fibronectin, E-selectin, L-selectin, P-selectin, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), or intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) under static and laminar flow conditions (wall shear stress = 1 dyn/cm2). hASCs were able to firmly adhere to Type I Collagen, fibronectin, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 substrates, but not to any of the selectins. Pretreatment with hypoxia increased the ability of hASCs isolated by liposuction to adhere to VCAM-1 and ICAM-1, but this effect was not seen in cells isolated by tissue excision. These results indicate that hASCs possess the ability to adhere key adhesion proteins, illustrate the importance of hASC harvest procedure, and suggest mechanisms for homing in a setting where interaction with inflamed or injured tissue is necessary.

Keywords: Adipose-derived stromal cells, hypoxia, liposuction, parallel plate flow chamber, adhesion cascade

INTRODUCTION

Adipose stromal cells (ASCs) are capable of differentiating into several different cell types [1-4] and incorporating into target tissues [5-8] following therapeutic delivery. What is not known is whether these cells, like bone marrow-derived cells, have the natural ability to preferentially home to inflamed and injured tissues to aid in tissue regeneration, and if they do, which adhesion molecules and epigenetic factors mediate this response. A central issue, from a therapeutic standpoint, is to understand if and how ASCs can be manipulated in vitro to augment this homing potential. A second issue of clinical relevance is: to what extent does the method of adipose tissue harvest impact the functional adhesion capabilities of ASCs? Filling these knowledge gaps requires a detailed characterization of ASCs’ capacity to functionally adhere to proteins exposed in an injured and/or diseased tissue, including cell adhesion molecules expressed by inflamed vascular endothelium and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins present in injured tissues.

The expression of surface adhesion molecules on ASCs has been previously examined using flow cytometry [9-12] (Tables 1 and 2), although no study to date has examined whether this expression translates to a functional ability to arrest and firmly adhere under physiologically relevant blood flow conditions. Here, we assess the functionality of proteins expressed by human ASCs (hASCs) in facilitating firm adhesion to key adhesion molecules present on inflamed or injured (activated) vascular endothelium and exposed extra-cellular matrix (ECM) at sites of tissue injury. In in vitro parallel plate flow chamber assays, which provide a controlled setting that yields reproducible and quantifiable readouts, we tested the following hypotheses: 1) that hASCs possess the ability to functionally adhere to inflammatory-mediating adhesion molecules, 2) that functional adhesion capabilities of hASCs are affected by oxygenation levels in the culture environment, and 3) that the method of hASC extraction (liposuction vs. lipoectomy) is critical in determining this cell populations’ ability to functionally adhere.

TABLE 1. Literature review of adipose-derived stromal cell (ASC) flow cytometry data relevant to adhesion assays performed in this investigation (percentages given when available).

All data is from cells collected by liposuction except Katz et al., 2005, which includes data using both liposuction and excision techniques (refer to Table 2). Cultured cells are all from normal culture oxygenation conditions.

| SVF | Passage 0 | Passage 1 | Passage 2 | Passage 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitchell et al., 2005 |

Meyerrose et al, 2007 |

Mitchell et al., 2005 |

Yanez et al., 2005 |

Zuk et al., 2002 | Aust et al., 2004 | Mitchell et al., 2005 |

Katz et al., 2005 | Mitchell et al., 2005 |

Gronthos et al., 2001 | Mitchell et al., 2005 |

|

|

CD11a (alphaL integrin) |

1 ± 1 | 0 | |||||||||

|

CD11b (alphaM integrin) |

27.31 ± 13.77 | <10% | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 1 ± 0.6 | 1 ± 0 | ||||||

|

CD18 (beta2 integrin) |

1 ± 0.5 | 0 | |||||||||

|

CD29 (beta1 integrin) |

47.7 ± 13.3 | 71.1 ± 30.3 | >80% | + | 99.8 ± 0.7 | 77.1 ± 23.6 | 97 ± 1.5 | 82.1 ± 21.2 | 98 ± 1 | 87.4 ± 18.8 | |

|

CD49d (alpha4 integrin) |

<10% | + | 78 ± 20 | 9 ± 2 | |||||||

|

CD49e (alpha5 integrin) |

>80% | 99.4 ± 0.3 | 98 ± 1 | 22 ± 7 | |||||||

|

CD51 (alphaV integrin) |

97 ± 3 | ||||||||||

|

CD61 (beta3 integrin) |

− | 30 ± 26 | |||||||||

|

CD49a (alpha1 integrin) |

35.6 ± 18.6 | 50.2 ± 28.3 | 58.8 ± 29.5 | 64.0 ± 29.1 | 53.4 ± 29.4 | ||||||

|

CD49b (alpha2 integrin) |

80 ± 13 | ||||||||||

| CD34 | 60.0 ± 11.5 | 50.24 ± 16.62 | 59.2 ± 25.4 | <10% | − | 21.5 ± 15.1 | 5.4 ± 6.3 | 28 ± 13 | 2.0 ± 2.0 | ||

TABLE 2. Unpublished breakdown of relevant flow cytometry data from Katz et al., 2005, by isolation method (excision N=3, liposuction N=5).

Cultured cells are all from normal culture oxygenation conditions.

| Passage 2 (Katz et al., 2005) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Excision | Liposuction | |

|

CD11a (alphaL integrin) |

1.1 ± 1.1 | 1.1 ± 0.8 |

|

CD11b (alphaM integrin) |

0.8 ± 0.7 | 0.5 ± 0.6 |

|

CD18 (beta2 integrin) |

0.4 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.4 |

|

CD29 (beta1 integrin) |

97.0 ± 1.5 | 96.6 ± 1.4 |

|

CD49d (alpha4 integrin) |

64.6 ± 24.0 | 88.4 ± 9.2 |

|

CD49e (alpha5 integrin) |

97.8 ± 1.2 | 97.9 ± 1.4 |

|

CD51 (alphaV integrin) |

97.8 ± 0.8 | 97.3 ± 3.3 |

|

CD61 (beta3 integrin) |

29.7 ± 33.2 | 40.5 ± 21.5 |

|

CD49b (alpha2 integrin) |

72.6 ± 12.4 | 88.7 ± 11.1 |

We used two different assays to answer these questions; the static adhesion and the laminar flow assays, both of which are widely-used [13, 14] and considered the standard for in vitro assessment of baseline functional adhesion capabilities of leukocytes [14, 15] and bone marrow-derived stromal cells [16]. The laminar flow assay examines the ability of a cell moving in a flow stream to be captured by the substrate, firmly adhere to the substrate, and remain firmly adhered in the presence of flow [17]. The static adhesion assay quantifies an already adherent cell’s ability to remain firmly adhered and resist fluid flow forces after flow is re-introduced [18]. Understanding the behavior of hASCs in these assays is highly relevant to future therapeutic applications—especially if these cells are to be used as an intravenously (i.v.) injected cell therapy, where initiation and persistence of firm adhesion in the presence of flow would be requisite for preferential homing (and subsequent extravasation) into injured and inflamed tissues.

The adhesion molecules P-selectin, E-selectin, L-selectin, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), Type I Collagen, and fibronectin were used in both assays because their ligands and/or receptors are expressed by hASCs [9] (Table 1). In addition, if hASCs are to be injected i.v. as therapeutic agents and expected to target injured tissues, they must rely on interactions with activated endothelium, where P-selectin, VCAM-1, ICAM-1 are rapidly upregulated [19], in order to firmly adhere and transmigrate into the injured tissue. It is also of interest to study the interactions of hASCs with ECM presumed to be present in the adipose stroma where hASCs reside endogenously (fibronectin, Type I Collagen) because these may also play a role in the mobilization and trafficking of tissue-resident hASCs to sites of injury.

hASCs show promise as therapeutic agents, particularly during ischemic injury [8, 20]. When injected i.v., hASCs have been shown to populate the ischemic tissue [20, 21], secrete proangiogenic growth factors [8], and prevent tissue necrosis [8, 20, 21]. Furthermore, because tissue hypoxia is often associated with ischemia and is also a known activating stimulus for hASCs [8, 22], it may aid in the mobilization and trafficking of both tissue-resident and therapeutically-delivered cells to injury sites. Thus, it is important to understand how hASCs behave in a hypoxic microenvironment with regards to their functional adhesion capabilities. As an activation scheme, hypoxia may represent an influential pretreatment strategy in clinical settings, if such treatment can be shown to increase preferential homing to inflamed or injured endothelium.

Harvested populations of hASCs are a heterogeneous mixture of different cell types, and previous studies have focused on the impact of hASC harvest site [23], donor BMI [10], and donor age [10, 24] on yield and differentiation capacity. Oedayrajsingh-Varma et al. (2006) showed that ASC extraction method impacted yield and growth characteristics in vitro [25]. We hypothesize that the method of extraction may also play a role in their functional adhesion potential and should be examined. Specifically, tissue harvested from clinical liposuction, a lengthy and tissue-disrupting procedure involving the repetitive application of mechanical force, could yield a different cellular composition than tissue obtained from clinical panniculectomy followed by laboratory liposuction, where all avenues of systemic cellular response are severed at the beginning of the procedure. It is therefore informative to examine whether these two populations have differing functional adhesion characteristics.

The goals of this study were to characterize the functional adhesion capabilities of hASCs, to understand the effects of hypoxia on this cell type, and to determine if the extraction method impacts the ability to adhere under fluid flow. Here, we report that hASCs possess the functional ability to firmly adhere Type I Collagen, VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and fibronectin and that they are able to survive prolonged periods of hypoxic culture. Additionally, the hASC response to hypoxia and subsequent increase in their ability to firmly adhere the proteins VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 is highly dependent on the extraction procedure. Only cell populations isolated by liposuction showed an increase in their ability to adhere following 48 hours of hypoxic preconditioning. This work is a necessary first step in determining if and how hASCs home to injured tissues and whether this capability can be exploited for i.v. injectable hASC-based therapies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Isolation and Preparation

All adipose tissue was obtained from either intraoperative suction lipectomy or laboratory liposuction of panniculectomy specimens. Subcutaneous adipose tissue was obtained from patients undergoing elective surgical procedures in the Department of Plastic Surgery at the University of Virginia that were approved by The University of Virginia’s Human Investigation Committee. Cells were isolated from adipose tissue using methods previously described [9]. Briefly, harvested tissue was washed with complete Hanks buffer, centrifuged and decanted to remove oil, and then enzymatically dissociated. The dissociated tissue was filtered to remove debris, and the resulting cell suspension was centrifuged. Pelleted stromal cells were then recovered and washed twice, filtered twice (250 μm mesh followed by 105 μm mesh), centrifuged, and decanted. Contaminating erythrocytes were lysed with an osmotic buffer, and the stromal cells were plated onto tissue culture plastic (10 cm dishes). Cultures were washed with buffer 24–48 hours after plating to remove unattached cells, and then re-fed with fresh medium. Plating and expansion medium consisted of DMEM/F12 with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic. Cultures were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 and fed two to three times per week. Cells were grown to confluence after the initial plating (p=0), typically within 10–14 days. Once confluent, the adherent cells were released with Accutase (Innovative Cell Technologies, Inc., San Diego, CA) and then re-plated at 2,000 cells/cm2. Cultures were passaged every 7–14 days until they were ready for testing. All hASCs used for analysis were considered early passage (p=3 at time of introduction to flow chamber). Human lung fibroblasts (hLFs) (WI-38 cell line, No. CCL-75, ATCC) were plated at approximately 2,000 cells/cm2 and were used as a control cell type in hypoxia verification.

Hypoxic Preconditioning

Groups of hASCs undergoing hypoxic conditioning were placed in a Modular Incubator Chamber (Billups-Rothenberg, Del Mar, CA) and perfused with 5% CO2, 95% N2 for 20 minutes to purge the chamber of oxygen. The chamber was then sealed and incubated at 37°C for 48 hours. This method maintains the cellular microenvironment at less than 14.9 mmHg oxygen (less than 2% O2) and was previously shown to induce hypoxia-inducible factor-1α(HIF-1α) expression in rat pulmonary endothelial cells [26].

The presence of a hypoxic cellular microenvironment was verified using the Hypoxyprobe-1 kit (Chemicon; Temecula, CA), designed to identify tissues and cells at oxygen tensions of < 10 mmHg. Cell suspensions were incubated in hypoxia as described above, and 200 μM Hypoxyprobe-1 (Pimonidazole Hydrochloride) was added. Cells were then harvested, fixed in 4% para-formaldehyde, and immunostained with provided antibody for pimonidazole adducts (1:50 dilution in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), 0.1% saponin, and 2% BSA).

Substrate Receptors

Recombinant human VCAM-1, recombinant human P-Selectin, recombinant human L-selectin, and recombinant human E-selectin were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Fibronectin, isolated from human fibroblasts, was purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). ICAM-1 was purified from human placenta lysates by R6.5 mAb affinity chromatography [27]. Briefly, the human placenta was homogenized in 20 mM Tris, pH 7.8, 140 mM NaCl, and 0.025% azide (TSA, pH 7.8) with 5 mM EDTA, 10 μM leupeptin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and 1% Triton X-100. The lysate was centrifuged first at 2000 rpm and then at 20,000 rpm for 15 min and 2 hours, respectively. After centrifugation, the lysate was passed over a column of cyanogen bromide-activated Sepharose 4B (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) coupled to R6.5 (2.1 mg/ml) twice. The column was then washed with TSA (20x bed volume), pH 7.6, containing 1% octylglucopyranoside (OG; Sigma) and eluted with TSA (5x bed volume), pH 11, containing 1% OG. The eluate was neutralized with 0.1 M glycine, pH3, 1% OG (10% v/v).

Preparation of adhesion substrates

The adhesion molecules P-selectin (1:100), E-selectin (1:100), L-selectin (1:100), Type I Collagen (1:1), fibronectin (1:100), VCAM-1 (1:100), and ICAM-1 (1:50) were diluted in PBS at the indicated concentrations. Polystyrene slides were cut from tissue culture dishes (Falcon 1058; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), and the adhesion molecule solutions were applied to the plates and allowed to adsorb for 2 hours at room temperature. The slides were blocked for nonspecific adhesion with 0.5% Tween 20 in PBS overnight at 4°C. The adhesion molecule densities were previously determined by saturation binding radioimmunoassay (RIA) according to previously established protocol [27]. The flow chamber was mounted over an inverted phase contrast microscope (Diaphot-TMD; Nikon, Garden City, NY) and observed at 20x magnification. For each substrate slide, 6 ml of DPBS solution was perfused over the substrate for a period of three minutes before all experiments to wash off any unbound protein or Tween 20.

Static Adhesion Assay

The slides coated with substrate proteins were used as the lower wall of the parallel plate flow chamber (Figure 1). Isolated hASCs at a concentration of 100,000-200,000 cells/ml in PBS with 0.1 mM Ca2+ and Mg2+ were perfused through the flow chamber. Flow was interrupted and the cells were allowed to settle on the chamber’s lower wall for six minutes, after which a flow at 1 dyn/cm2 wall shear stress was applied. After this re-introduction of flow, the number of hASCs that remained bound for greater than 10 seconds were designated as ‘firmly adhered’ and recorded. Data are presented as the percentage of cells originally in a field of view (FOV) that remain substrate bound.

FIGURE 1. Parallel plate flow chamber set-up.

Both laminar flow and static assays are facilitated using this parallel plate flow chamber device though which cells are perfused and allowed to interact with the substrate.

Laminar Flow Adhesion Assay

The laminar flow assay tests whether a cell in the presence of a flow field can firmly adhere to a substrate containing a bound adhesion molecule. This assay is particularly relevant for determining the capability of circulating cells (e.g., progenitor cells and leukocytes) to firmly adhere to specific ligands (e.g., adhesion molecules expressed by vascular endothelium). Slides previously coated with adhesion proteins were incorporated into the parallel plate flow chamber where they were used as the lower wall (Figure 1). Cells were perfused though the flow chamber at a concentration of 0.2 × 106 cells/ml and at a wall shear stress of 1 dyn/cm2. Twenty FOV were visually examined between one and three minutes post-introduction of flow, and the accumulation of adherent hASCs was recorded and averaged for each substrate. hASCs that were firmly adherent rapidly extended lamellipodia and appeared phase-dark.

Data Acquisition

A Kodak MotionCorder Analyzer model 1000 camera (Eastman Kodak, Motion Analysis System Division, San Diego, CA) was used for tracking adipose-adhesive events with the substrates at a frame rate of 30 frames/second.

Statistical Analysis

All results are presented in the form of mean ± standard deviation. All comparisons were made using the statistical analysis tools provided by SigmaPlot 5.0 (Systat, Inc., Point Richmond, CA). Data in Figure 2 was analyzed for statistical significance using a paired t-test that compared hASCs on a particular substrate to the same population (donor and passage) of hASCs on the identical substrate in the presence of Tween 20 (which blocks non-specific adhesion) during the same experimental trial. In this way, a “significant” data point is one in which hASCs bound the substrate to a significantly greater extent than is expected by chance non-specific binding. Data in Figure 4 were tested for normality and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by non-paired Tukey’s t-test. In all cases, statistical significance was asserted at p<0.05. In terms of the reported sample sizes, “N” refers to the number of individual donor patients from which hASCs were harvested, whereas “n” refers to the number of independent trials (replicates) that were run with a particular assay condition (using hASCs from the same and/or different donors).

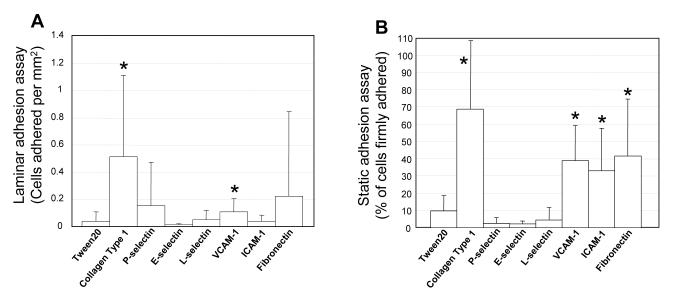

FIGURE 2. hASCs functionally adhere to specific proteins.

A) Static adhesion assay. Average percentage of hASCs initially in a field of view that remain firmly adhered to Type I Collagen (n=3, N=3), VCAM-1 (n=16, N=10), ICAM-1 (n=16, N=9), fibronectin (n=11, N=8), P-selectin (n=4, N=4), E-selectin (n=5, N=4), or L-selectin (n=5, N=4) after the introduction of flow (wall shear stress equal to 1 dyn/cm2). B) Laminar flow assay. Average number of cells firmly adhered per mm2 to Collagen Type I (n=3, N=3), VCAM-1 (n=16, N=7), ICAM-1 (n=15, N=7), and fibronectin (n=12, N=7). (± S.D.; * = statistically different from Tween 20 control, p≤0.05).

FIGURE 4. Increase in hASC functional adhesion after culture in hypoxic conditions is highly dependent on cell isolation procedure.

A) Static adhesion assay. Average percentage of normal culture condition (n=5, N=2) and hypoxia-treated (n=7, N=2) liposuction-derived hASCs initially in a FOV that remained adherent to VCAM-1 after induction of flow (wall shear stress equal to 1 dyn/cm2 initiated after six minutes). Data was pooled from two female donors of similar age (39 and 31) and similar BMI (23.2 and 20.8) who both received liposuction procedures. Conversely, hASCs isolated by excision procedures showed no statistically significant change in their ability to adhere VCAM-1 (normoxia: n=3, N=2) following 48 hours of hypoxic culture (hypoxia: n=4, N=2) (data not shown). (± S.D.; * = statistically different from normally cultured cells on same substrate, p≤0.05). B) Laminar flow assay. Firm adhesion of hypoxia-cultured and normally cultured liposuction-derived hASCs to VCAM-1 (n=4 for both normoxia and hypoxia, N=1) and ICAM-1 (n=4 for both normoxia and hypoxia, N=1). Data is from a 31-year-old female donor (BMI 20.8). The differential response to hypoxic culture may be partially dependent on the specific adhesion molecule: hASCs from the same donor did not significantly increase their ability to adhere fibronectin (n=2 for both normoxia and hypoxia, N=1) (data not shown). Conversely, hASCs isolated from a female 37-year-old female donor (BMI 25.8) by panniculectomy excision procedures exhibited no significant change in their ability to firmly adhere VCAM-1 (n=2 for both normoxia and hypoxia, N=1) or ICAM-1 (n=2 for both normoxia and hypoxia, N=1) following 48 hours hypoxic culture (data not shown). (± S.D.; * = statistically different from normally cultured cells on same substrate, p≤0.05).

RESULTS

Firm adhesion of hASCs to immobilized proteins

Laminar Flow Adhesion Assay

Results show that hASCs firmly adhere to Type I Collagen and VCAM-1 when compared to paired negative control groups (where adhesion interactions are physically blocked by Tween 20) (Figure 2A). Interestingly however, our data indicate that despite expressing known ligands for the selectins, ICAM-1, and fibronectin [9] (also see Tables 1 and 2), hASCs are not able to functionally adhere to these ligands in this in vitro laminar flow assay. Data was pooled without regard to donor age, gender, or BMI.

Static Adhesion Assay

Static adhesion assays were performed to establish whether hASCs can withstand blood flow-induced shear forces characteristic of the venous circulation (wall shear stress equal to 1 dyn/cm2) after being allowed time to firmly adhere (six minutes). The results of these experiments show that hASCs functionally bind Type I Collagen and VCAM-1 (Figures 2A and 2B) and suggest an ability to interact with and firmly adhere ICAM-1 and fibronectin (Figure 2B) in the static adhesion assay.

hASCs survive in vitro hypoxic culture

Separate cultures of hLFs and hASCs were placed in hypoxic culture for 48 hours, but only the hASCs survived this prolonged period of hypoxia. hASCs maintained their spread, cobblestone morphology with no observed instances of extensive cell death, while hLF viability was negligible after the hypoxia treatment due to global apoptosis, as assessed by cell morphology (data not shown). Hypoxia was verified by immunofluorescence analysis of hASCs cultured under normal (Figure 3A) and hypoxic conditions (Figure 3B).

FIGURE 3. Liposuction-derived hASCs show increased functional adhesion capabilities in response to 48 hours of hypoxic culture, while excision-derived hASCs do not.

A) Micrograph showing hASCs grown under normal culture conditions labeled with Hypoxyprobe-1 for presence of pimonidazole adducts compared with (B) hypoxic culture control.

Isolation procedure determines hASC response to hypoxia and subsequent increase in functional adhesion capabilities

The ability of hASCs obtained from both liposuctioned and excised tissues to functionally bind adhesion molecules was assayed in the static adhesion and laminar flow assays after 48 hours of hypoxic or normal culture conditions. While hASCs derived from liposuctioned tissue and from excised tissue appeared morphologically similar following 48 hours of hypoxic culture, only liposuction-derived hASCs increased their capability to functionally adhere. Donor hASCs isolated through liposuction procedures and exposed to hypoxia show a significant increase over cells cultured in normal culture conditions (68% increase) in their ability to functionally bind the adhesion molecule VCAM-1 (Figure 4A) in the static adhesion assay. Data here was pooled from two female donors (N=2) of similar age (39 and 31) and similar BMI (23.2 and 20.8, respectively) who both underwent liposuction procedures; this was done to limit the impact of donor variability on the reported results (n=5 normal culture, n=7 hypoxia). Conversely, hASCs isolated by excision procedures and cultured in hypoxia exhibited no significant change in their ability to adhere to either VCAM-1 or ICAM-1, as compared to those cultured in normal culture conditions (data not shown).

In the laminar flow assay, hASCs also exhibited different responses to hypoxia based on the method of harvest (liposuction vs. excision). Following 48 hours hypoxic culture, hASCs isolated by liposuction showed dramatically increased firm adhesion to the proteins VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 (Figure 4B). This differs from the behavior of excised hASCs, which show no significant response to an identical treatment of prolonged hypoxic culture or any change in their ability to adhere VCAM-1 or ICAM-1 in the laminar flow assay (data not shown). This figure depicts the results from a single donor in order to control for variables such as BMI, gender, and age. All immobilized proteins were tested for their interactions with hypoxia-cultured hASCs isolated by both liposuction and excision procedures, but no significant differences in adhesion capabilities were observed with the other immobilized proteins (Type I collagen, selectins, and fibronectin; data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that hASCs functionally adhere to Type I Collagen and VCAM-1, but not to ICAM-1, fibronectin, E-, L-, or P-selectin under conditions of physiological laminar flow within a parallel plate flow chamber. During static adhesion testing, it was found that hASCs firmly adhere to Type I Collagen, VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and fibronectin, but not to any of the selectins. An important aspect of this finding is that hASCs were able to firmly adhere to adhesion proteins in the absence of the selectins. While interactions with a substrate coated with both a selectin and an integrin-binding adhesion molecule (e.g., VCAM-1 or ICAM-1) may allow higher binding efficiencies or enable rolling, the ability of hASCs to firmly adhere independent of any selectin-mediated activity is of particular interest. With the exception of monocytes, most circulating cells have been found to be dependent on selectins in order for firm adhesion to occur [19, 28]. In this way, hASCs may be more like monocytes in that they do not need to proceed through the adhesion cascade sequentially in order to extravasate into inflamed tissues from the circulation [28, 29, 30]. Of interest, bone marrow-derived hematopoietic stem cells have been shown to interact with selectins via PSGL-1 [16], though the presence of this capability in an hASC population was not investigated here.

It should be mentioned, however, that our experiments did not measure transient interactions with the substrate, such as rolling velocity and formation of catch or slip bonds, so although no firm adhesion was observed for substrates comprised of either L-, P-, or E-selectin, there may have been undetected interactions between hASCs and these molecules. Moreover, our negative results do not preclude the possibility that these adhesion molecules play a significant role in vivo, and this should be investigated in future studies.

The observation that hASCs functionally bind to integrin-binding adhesion molecules at physiological flow levels was unexpected and indicates that hASCs have the ability to firmly adhere to proteins expressed along the luminal surface of activated endothelium and in the ECM. This, and the fact that adipose tissue is well vascularized (has immediate access to the microcirculation) and is present throughout the body may indicate that hASCs represent a locally available emergency supply of regenerative cells in case of sudden or severe vascular injury.

Previously published flow cytometry data summarized in Table 1 show that despite differing durations in culture, many of the markers relevant to cell adhesion remain at consistent expression levels. According to previous analyses of hASCs by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS), hASCs express the binding partners for VCAM-1 (VLA-4), and fibronectin (αvβ3) [9] (Table 1), so it is not surprising that hASCs have the ability to bind to these substrates. In contrast, integrins such as αL and β2 are marginally detectable on ASCs even though the data from this study show that cells are able to remain firmly adhered to ICAM-1 when flow is reintroduced—an interaction thought to be primarily mediated by LFA-1. This discrepancy illustrates the limitations of flow cytometry in predicting the adhesion capabilities of ASCs. However, this should not be too surprising as the subpopulation of hASCs responsible for observed therapeutic benefits following the delivery of a heterogeneous cell mixture has not been identified and may be a population as small as 1% of the total number of cells in culture.

In Table 2, pooled data from Katz et al., 2005, has been partitioned by isolation method. Interestingly, this shows that there is little difference between the adhesion molecule expression patterns of cells isolated by excision and liposuction, despite the differences identified in their functional adhesion capabilities, nor is there any indication that either cell population would respond differently to a pre-treatment of hypoxia. It is likely then that the differing response to hypoxia by hASCs isolated by excision versus liposuction is not due to differences in their baseline adhesion profiles, but rather due to some other mechanism, such as selective culture of a subpopulation in liposuctioned tissue induced by hypoxia.

Hypoxia can promote cell differentiation, proliferation, changes in protein and RNA expression, and up-regulate the secretion of numerous growth factors and chemokines in many cell types, including endothelial [31] and smooth muscle cells [32]. Recent studies have also shown that ASCs are responsive to hypoxia and that this stimulus promotes the secretion of the pro-angiogenic growth factor VEGF [8], but reduces proliferation [33] and attenuates adipogenic, chondrogenic, and osteogenic differentiation [34, 35]. Here, we show that hASCs survive 48 hours of conditioning in hypoxic culture conditions and that this stimulus impacts the ability of hASCs to firmly adhere. Moreover, prolonged exposure to a hypoxic environment may further enhance the secretory, differentiation, and proliferative capacity of hASCs [8, 22], and their ability to survive such conditions makes this a viable approach for cell activation prior to therapeutic delivery.

However, we show that the response of hASCs to hypoxic culture is strongly linked to the technique that is used to extract them from the donor. When cultured in hypoxic conditions, hASCs isolated by panniculectomy excision showed no increase in ability to bind VCAM-1 compared to cells cultured in normoxia, but hASCs isolated by liposuction exhibited an increase in their ability to firmly adhere VCAM-1 (in both laminar flow and static experiments) and ICAM-1 (only in laminar flow experiments). This implies that liposuction-derived hASCs, or some subpopulation therein, has an adhesion program that is activated when the cell experiences hypoxic conditions. The sharp delineation with regard to post-treatment adhesion programs between liposuction and excision isolation techniques in age and BMI-matched donors suggests that there is an important difference in either the population of cells obtained by each method or a phenotypic change caused by one method that is not caused by the other. It is possible that cells obtained by liposuction have experienced some degree of phenotypic change caused by mechanical agitation from the liposuction cannula or infusion of large boluses of saline solution; however, it is unlikely that such a phenotypic change would persist after three passages of expansion in culture [35, 36]. A more likely explanation for these observations is that there is some population present or enriched in the liposuction aspirate that is not present (or present to a lesser degree) in the panniculectomy excision. If a subpopulation is the cause of higher binding to adhesion proteins after hypoxia, it may be that either a new cell type has infiltrated the liposuction samples during collection or that the hypoxia has provided selection pressure allowing for those cells with more ability to bind proteins present on activated endothelium to dominate the phenotype, whether that ability is constitutive or activated by the hypoxia itself.

We present that hASCs possess a functional ability to firmly adhere to proteins present in the ECM as well as those expressed by activated vascular endothelium. Extraction technique (liposuction vs. lipoectomy) impacts the adhesion potential of hASCs and their response to hypoxic culture. Future work is necessary to determine the complete adhesion profiles of hASCs binding these substrates under both normal culture conditions and hypoxic incubation. If a subpopulation of cells, such as bone marrow-derived stem cells infiltrating the tissue during liposuction, is responsible for the observed adhesion, many of the beneficial characteristics of hASCs, such as plasticity and regenerative properties, may be due to circulating progenitor cells and not to adipose-resident cells [37]. If, however, the cells that are responsible for the firm adhesion in each of these experiments are a subpopulation of the adipose-resident cells in the donor tissue, that subpopulation could be enriched or selected for using a hypoxia pretreatment regimen in clinical applications. Toward this end, this work lays a foundation for further investigation into the ability of ASCs to act as regenerative agents in injured or inflamed tissues through differential, functional adhesion.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Jeffrey DiVetro and Dr. Chris Paschall for their assistance with the adhesion assays and for providing us with the isolated ICAM-1 protein, Dr. Lisa Palmer for her assistance with the hypoxia preconditioning of hASCs, as well as the Department of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Virginia for their support.

This work was supported by the University of Virginia Department of Biomedical Engineering.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gronthos S, Franklin DM, Leddy HA, Robey PG, Storms RW, Gimble JM. Surface protein characterization of human adipose tissue-derived stromal cells. J Cell Physiol. 2001;189:54–63. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuk PA, Zhu M, Ashjian P, De Ugarte DA, Huang JI, Mizuno H, Alfonso ZC, Fraser JK, Benhaim P, Hedrick MH. Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:4279–95. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-02-0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wan DC, Shi YY, Nacamuli RP, Quarto N, Lyons KM, Longaker MT. Osteogenic differentiation of mouse adipose-derived adult stromal cells requires retinoic acid and bone morphogenetic protein receptor type IB signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12335–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604849103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeng Q, Li X, Beck G, Balian G, Shen FH. Growth and differentiation factor-5 (GDF-5) stimulates osteogenic differentiation and increases vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) levels in fat-derived stromal cells in vitro. Bone. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kubis N, Tomita Y, Tran-Dinh A, Planat-Benard V, Andre M, Karaszewski B, Waeckel L, Penicaud L, Silvestre JS, Casteilla L, Seylaz J, Pinard E. Vascular fate of adipose tissue-derived adult stromal cells in the ischemic murine brain: A combined imaging-histological study. Neuroimage. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shigemura N, Okumura M, Mizuno S, Imanishi Y, Nakamura T, Sawa Y. Autologous transplantation of adipose tissue-derived stromal cells ameliorates pulmonary emphysema. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:2592–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strem BM, Zhu M, Alfonso Z, Daniels EJ, Schreiber R, Beygui R, MacLellan WR, Hedrick MH, Fraser JK. Expression of cardiomyocytic markers on adipose tissue-derived cells in a murine model of acute myocardial injury. Cytotherapy. 2005;7:282–91. doi: 10.1080/14653240510027226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rehman J, Traktuev D, Li J, Merfeld-Clauss S, Temm-Grove CJ, Bovenkerk JE, Pell CL, Johnstone BH, Considine RV, March KL. Secretion of angiogenic and antiapoptotic factors by human adipose stromal cells. Circulation. 2004;109:1292–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121425.42966.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz AJ, Tholpady A, Tholpady SS, Shang H, Ogle RC. Cell surface and transcriptional characterization of human adipose-derived adherent stromal (hADAS) cells. Stem Cells. 2005;23:412–23. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aust L, Devlin B, Foster SJ, Halvorsen YD, Hicok K, du Laney T, Sen A, Willingmyre GD, Gimble JM. Yield of human adipose-derived adult stem cells from liposuction aspirates. Cytotherapy. 2004;6:7–14. doi: 10.1080/14653240310004539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshimura K, Shigeura T, Matsumoto D, Sato T, Takaki Y, Aiba-Kojima E, Sato K, Inoue K, Nagase T, Koshima I, Gonda K. Characterization of freshly isolated and cultured cells derived from the fatty and fluid portions of liposuction aspirates. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208:64–76. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell JB, McIntosh K, Zvonic S, Garrett S, Floyd ZE, Kloster A, Di Halvorsen Y, Storms RW, Goh B, Kilroy G, Wu X, Gimble JM. Immunophenotype of human adipose-derived cells: temporal changes in stromal-associated and stem cell-associated markers. Stem Cells. 2006;24:376–85. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ham AS, Goetz DJ, Klibanov AL, Lawrence MB. Microparticle adhesive dynamics and rolling mediated by selectin specific antibodies under flow. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2006 doi: 10.1002/bit.21153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finger EB, Puri KD, Alon R, Lawrence MB, von Andrian UH, Springer TA. Adhesion through L-selectin requires a threshold hydrodynamic shear. Nature. 1996;379:266–9. doi: 10.1038/379266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawrence MB, Springer TA. Neutrophils roll on E-selectin. J Immunol. 1993;151:6338–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenberg AW, Kerr WG, Hammer DA. Relationship between selectin-mediated rolling of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and progression in hematopoietic development. Blood. 2000;95:478–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Springer TA. Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell. 1994;76:301–14. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kiely JM, Luscinskas FW, Gimbrone MA., Jr. Leukocyte-endothelial monolayer adhesion assay (static conditions) Methods Mol Biol. 1999;96:131–6. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-258-9:131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ley K. Molecular mechanisms of leukocyte recruitment in the inflammatory process. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;32:733–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Planat-Benard V, Silvestre JS, Cousin B, Andre M, Nibbelink M, Tamarat R, Clergue M, Manneville C, Saillan-Barreau C, Duriez M, Tedgui A, Levy B, Penicaud L, Casteilla L. Plasticity of human adipose lineage cells toward endothelial cells: physiological and therapeutic perspectives. Circulation. 2004;109:656–63. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000114522.38265.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miranville A, Heeschen C, Sengenes C, Curat CA, Busse R, Bouloumie A. Improvement of postnatal neovascularization by human adipose tissue-derived stem cells. Circulation. 2004;110:349–55. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000135466.16823.D0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho HH, Bae YC, Jung JS. Role of Toll-like Receptors on Human Adipose-derived Stromal Cells. Stem Cells. 2006 doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prunet-Marcassus B, Cousin B, Caton D, Andre M, Penicaud L, Casteilla L. From heterogeneity to plasticity in adipose tissues: site-specific differences. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:727–36. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi YY, Nacamuli RP, Salim A, Longaker MT. The osteogenic potential of adipose-derived mesenchymal cells is maintained with aging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1686–96. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000185606.03222.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oedayrajsingh-Varma MJ, van Ham SM, Knippenberg M, Helder MN, Klein-Nulend J, Schouten TE, Ritt MJ, van Milligen FJ. Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cell yield and growth characteristics are affected by the tissue-harvesting procedure. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:166–77. doi: 10.1080/14653240600621125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer LA, Semenza GL, Stoler MH, Johns RA. Hypoxia induces type II NOS gene expression in pulmonary artery endothelial cells via HIF-1. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L212–9. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.2.L212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DiVietro JA, Smith MJ, Smith BR, Petruzzelli L, Larson RS, Lawrence MB. Immobilized IL-8 triggers progressive activation of neutrophils rolling in vitro on P-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1. J Immunol. 2001;167:4017–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frenette J, Chbinou N, Godbout C, Marsolais D, Frenette PS. Macrophages, not neutrophils, infiltrate skeletal muscle in mice deficient in P/E selectins after mechanical reloading. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R727–32. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00175.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Charriere G, Cousin B, Arnaud E, Andre M, Bacou F, Penicaud L, Casteilla L. Preadipocyte conversion to macrophage. Evidence of plasticity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9850–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jung U, Ley K. Mice lacking two or all three selectins demonstrate overlapping and distinct functions for each selectin. J Immunol. 1999;162:6755–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stenmark KR, Fagan KA, Frid MG. Hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Circ Res. 2006;99:675–91. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000243584.45145.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schultz K, Fanburg BL, Beasley D. Hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha promote growth factor-induced proliferation of human vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H2528–34. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01077.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Follmar KE, Decroos FC, Prichard HL, Wang HT, Erdmann D, Olbrich KC. Effects of Glutamine, Glucose, and Oxygen Concentration on the Metabolism and Proliferation of Rabbit Adipose-Derived Stem Cells. Tissue Eng. 2006 doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.3525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee JH, Kemp DM. Human adipose-derived stem cells display myogenic potential and perturbed function in hypoxic conditions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;341:882–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malladi P, Xu Y, Chiou M, Giaccia AJ, Longaker MT. Effect of reduced oxygen tension on chondrogenesis and osteogenesis in adipose-derived mesenchymal cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1139–46. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00415.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chennazhy K. Prasad, Krishnan LK. Effect of passage number and matrix characteristics on differentiation of endothelial cells cultured for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5658–67. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Badiavas EV, Abedi M, Butmarc J, Falanga V, Quesenberry P. Participation of bone marrow derived cells in cutaneous wound healing. J Cell Physiol. 2003;196:245–50. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]