Abstract

In October 2007, Madagascar conducted a nationwide integrated campaign to deliver measles vaccination, mebendazole, and vitamin A to children six months to five years of age. In 59 of the 111 districts, long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) were delivered to children less than five years of age in combination with the other interventions. A community-based, cross-sectional survey assessed LLIN ownership and use six months post-campaign during the rainy season. LLIN ownership was analyzed by wealth quintile to assess equity. In the 59 districts, 76.8% of households possessed at least one LLIN from any source and 56.4% of households possessed a campaign net. Equity of campaign net ownership was evident. Post-campaign, the LLIN use target of ≥ 80% by children less than five years of age and a high level of LLIN use (69%) by pregnant women were attained. Targeted LLIN distribution further contributed to total population coverage (60%) through use of campaign nets by all age groups.

Introduction

Insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) are a highly effective means of malaria prevention and form a cornerstone of the global malaria control strategy. Use of ITNs reduces the incidence of clinical malaria by 50% and reduces all-cause child mortality by almost 20%.1 ITN use during pregnancy has also been shown to reduce the prevalence of low birth weight deliveries and miscarriages/stillbirths.2 At high levels of coverage, community-wide benefits of ITN use have been demonstrated that extend beyond the personal protection afforded by sleeping under an ITN through a mass effect on the Anopheles vector population.3–5

Recent years have seen accelerated malaria control efforts and establishment of revised consensus targets of ≥ 80% ITN use by pregnant women and young children by 2010.6–8 In addition, new Roll Back Malaria universal coverage targets aim to protect the entire population at risk by 2010 through an approach that includes household ownership of one long-lasting insecticidal net (LLIN) for every two inhabitants.9 Ongoing monitoring and evaluation of national malaria control operations has shown that ITN coverage is increasing in many countries, and some are well on the way to achieving these revised targets.10–12

The introduction of LLINs that retain insecticidal activity for 3–5 years, along with free distribution, has contributed greatly to recent increases in ITN coverage. In many countries, LLIN coverage has increased through a combination of delivery systems including routine public health services (antenatal clinics, routine vaccination visits), subsidized social marketing, and integrated mass campaigns.11,13,14 In particular, integrated campaigns that deliver LLINs in conjunction with vaccination, de-worming and other health interventions have achieved rapid increases in LLIN coverage and improved the equity of net ownership.11,15,16 The cost-effectiveness of integrated delivery versus social marketing has been assessed and compared.17,18 Despite debate on both sides.19–21 it has been suggested that these strategies are complementary and may serve to increase overall community-wide coverage.14

Madagascar is located off of the eastern coast of Africa and has a population of approximately 19 million persons. Administratively, the country is divided into 22 regions and 111 districts. In Madagascar, malaria is a major public health problem responsible for more than one million clinical cases per year.22 Malaria is endemic in 90% of Madagascar. However, its entire population is considered to be at risk. There are four distinct malaria epidemiologic zones with stable, perennial transmission on the eastern and western coasts, and unstable, seasonal transmission in the central highlands and in the southern region. The ITN distribution strategy in Madagascar differs by geographic region. The highly endemic eastern coast is the highest priority area and was the first targeted for ITN distribution, with distribution later expanding to the western coast and recently to the southern region. Indoor residual spraying has been the main vector control intervention in the epidemic-prone central highlands as outlined in the national malaria control strategy, and, until the present time, this area has not been targeted for generalized ITN distribution.

ITNs have been available in Madagascar since 2001 through commercial social marketing channels,23 and routine distribution commenced in 10 districts in 2005.24 According to the 2003–2004 Demographic and Health Survey, ownership of any type of bed net (treated or untreated) ranged from 11% to 34% in the central and southern provinces and from 62% to 82% in the eastern and western provinces.25

In October 2007, the Government of Madagascar, in conjunction with international partners, launched a national campaign directed to 2.8 million children less than five years of age for measles vaccination, mebendazole, and vitamin A in all 111 districts nationwide, and integrated the distribution of LLINs in the 59 districts in the western and southern regions of the country, which had not previously benefited from large-scale LLIN distribution. The campaign was led by the Madagascar Ministry of Health and Family Planning as a collaborative effort among the American Red Cross; the Canadian International Development Agency; the Canadian Red Cross; the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies; the Madagascar Red Cross; Malaria No More; the Measles Initiative; Population Services International; the President's Malaria Initiative; Roll Back Malaria; Sumitomo Chemical; the United National International Children's Fund; the United Nations Foundation; the U.S. Agency for International Development; the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Vestergaard Frandsen; the World Health Organization; and other organizations.

More than 1.5 million Olyset and Permanet LLINs were distributed by the Ministry of Health and the Madagascar Red Cross at fixed and mobile distribution points, comprising health centers and other community landmarks, at the fokontany (smallest administrative unit) level. The distribution strategy was one LLIN per eligible child up to a maximum of two LLINs per household. LLINs were also provided to pregnant women at distribution points in roughly half of the 59 districts. The 32 districts along the eastern coast of Madagascar, which are routinely targeted for ITN distribution, and 20 districts in the central highlands, did not receive free LLINs as part of the integrated measles/malaria campaign. A social mobilization campaign was conducted by the Ministry of Health and the Madagascar Red Cross one week before the campaign to sensitize the local population on the location and timing of the campaign. In addition, for one week post-campaign the Madagascar Red Cross conducted hang-up activities in the communities to sensitize the local population on the proper way to hang and use nets.

To evaluate the impact of the integrated campaign on LLIN ownership and use, a cross-sectional national household survey was conducted six months post-campaign during the rainy season. Because of its programmatic importance to the national malaria control strategy, and to understand the current status of malaria control efforts in Madagascar, we present estimates of LLIN ownership and use for the malaria-endemic area of Madagascar (91 of 111 districts). However, because of differences in LLIN distribution methods and timelines in other parts of the country, the main focus of this report is on post-campaign LLIN ownership, equity of LLIN ownership, and use of LLINs in the 59 districts where LLIN distribution was integrated during the October 2007 campaign.

Materials and Methods

Study design.

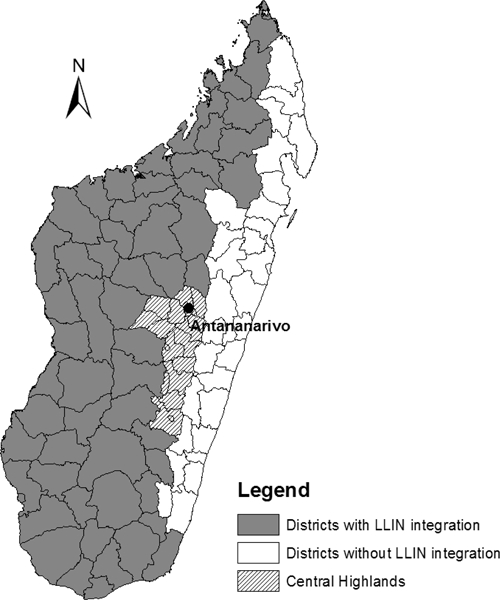

A two-stage cluster sampling method was applied, followed by simple random sampling at the household level. The country was divided into three operational zones corresponding to areas where 1) the Ministry of Health or 2) the Madagascar Red Cross distributed LLINs during the campaign, and 3) areas where no LLIN integration occurred (Figure 1). In each zone, 10 districts were selected by probability proportional to size sampling, i.e., areas with larger population had proportionally larger chance of being selected. In each district, six fokontany were selected by using probability proportional to size sampling. Sampling was based on projected 2008 population estimates extrapolated from the most recent census, which took place in 2003.26 Although the survey sampled nationally, enabling us to generate estimates for the malaria-endemic area, this report mainly focuses on the 59 districts (areas 1 and 2) where LLINs were distributed during the campaign. If a fokontany was inaccessible for logistic reasons, a previously selected alternate was used. Within the 59 districts with LLIN distribution, replacements were made for 13 of 120 fokontany (10.8%) that were inaccessible because of road conditions and flooding after the January–February 2008 cyclone season. A total of 2,880 households were selected for interviews in the 59 districts.

Figure 1.

Map of Madagascar showing the 59 districts where free long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) were distributed during the October 2007 integrated campaign (solid gray). LLINs were not distributed during the integrated campaign in the 32 malaria-endemic east coast districts (white) and the 20 epidemic-prone central highland districts (hatched). The malaria endemic area is represented by the 91 solid gray or white districts.

Data collection was carried out by using personal digital assistants (MyPal 696; Asus, Fremont, CA) equipped with internal global positioning systems receivers. The personal digital assistants/global positioning system–based sampling and data collection procedure has been described by Vanden Eng and others.27 Briefly, all households in a fokontany were mapped by survey teams, and 30 households (24 primary and 6 alternate) were subsequently selected from the household listing by using a built-in random sampling frame (GPS sample; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA). Surveyors conducted a software-guided interview at selected households using a pre-programmed questionnaire (developed using Visual CE 10.2; Syware Inc., Cambridge, MA). Households were revisited if no one was available for interview on the first attempt; if no respondent was available after two attempts a randomly selected alternate household was used. No replacement was made for households that refused to participate.

A household was defined as all persons who eat out of the same food pot and recognize the same head of household in accordance with other surveys in Madagascar. An ITN was defined as a conventional net that was reported to have been treated with insecticide within the past six months. LLINs were identified by brand (Olyset, Permanet, or Super Moustiquaire) by visual inspection of the net when possible. Campaign LLINs were defined as either Olyset or Permanet that were reported to have been received by an eligible child or pregnant woman during the October 2007 integrated campaign. Net use was defined as reported use the previous night. Wealth quintiles were derived by using the scoring system for economic indicators from the 2004 Demographic and Health Survey. The equity ratio for an indicator was calculated as the proportion in the poorest quintile divided by the proportion in the wealthiest quintile, such that a value of 1 suggests perfect equity between the poorest and wealthiest households. An individual fokontany was classified as urban or rural by officials at the Madagascar Ministry of Health, Family Planning and Social Protection.

Statistical analysis.

Data from personal digital assistants were synchronized into a Microsoft (Redmond, WA) Access database for data cleaning, management, and analysis. Analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The PROC SURVEYFREQ function was used to estimate proportions and confidence intervals taking into account clustering at the fokontany level and stratified by operational zone. Estimates and standard errors were weighted based on the probability of being selected. A Rao-Scott chi-square test was used to test for differences in proportions.

Ethical clearance.

The cross-sectional survey was reviewed and approved by the Madagascar Ministry of Health, Family Planning and Social Protection (Antananarivo, Madagascar) and the institutional review boards of HealthBridge (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Informed consent was obtained from all respondents and caregivers after the study was explained in the local language.

Results

Demographics.

In the 120 fokontany that were sampled from the 59 districts with campaign net distribution, 2,860 of 2,880 selected households were surveyed (refusal rate = 0.7%) (Table 1). Interviews collected data on 12,032 persons, including 2,369 children less than five years of age and 2,756 women of reproductive age. Approximately 11.6% of women of reproductive age were pregnant at the time of the survey. The median household size of those sampled was 4.0 persons (interquartile range = 3.0–5.0). Of households surveyed, 56.0% had at least one child less than five years of age.

Table 1.

Number of households interviewed six months after the 2007 integrated campaign for use of long-lasting insecticidal nets in 59 districts of Madagascar by urban/rural and wealth status

| Group | No. (%) households |

|---|---|

| Total | 2,860 |

| Urban | 237 (8.3) |

| Rural | 2,623 (91.7) |

| Poorest quintile | 637 (22.3) |

| Second quintile | 755 (26.4) |

| Third quintile | 548 (19.2) |

| Fourth quintile | 453 (15.8) |

| Wealthiest quintile | 467 (16.3) |

LLIN ownership.

Post-campaign household ownership of ≥ 1 LLIN in the 59 districts was 76.8%, and 34.0% of households owned ≥ 2 LLINs (Table 2). The average number of LLINs per household was 1.2 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.1–1.3). Household ownership of ≥ 1 LLIN from the campaign was 56.4%, and 80.1% of households with an eligible child reported receiving ≥ 1 LLIN from the campaign. Of all LLINs that were reported to have been received from the campaign, 98.3% were identified as either Olyset or Permanet, corresponding with expected brand distribution districts. The 2007 integrated campaign accounted for 64.0% of all LLINs in the 59 districts (Table 3). Commercial sources and routine free distribution through public health services accounted for a lower proportion of LLINs (30.7% and 3.3%, respectively). Conventional ITNs represented a negligible proportion (approximately 1%) of all nets.

Table 2.

Household ownership and hanging rates for any type of bed net and long-lasting insecticidal nets in 59 districts of Madagascar six months after the 2007 integrated campaign*

| Group | % Households (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| HH with any net† | 83.9 (81.3–86.5) |

| HH with ≥ 1 LLIN | 76.8 (73.8–79.9) |

| HH with ≥ 2 LLIN | 34.0 (30.0–37.9) |

| HH with any net hanging‡ | 78.4 (75.0–81.9) |

| HH with LLIN hanging‡ | 71.5 (67.9–75.1) |

CI = confidence interval; LLIN = long-lasting insecticidal net; HH = household,

Any net refers to an untreated net, a conventional net treated with insecticide within the past six months (insecticide-treated net), or an LLIN.

Nets reported as hanging the previous night.

Table 3.

Post-campaign sources of long-lasting insecticidal nets in 59 districts of Madagascar*

| Source | % LLINs (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Total LLINs, no. | 3,482 |

| Campaign† | 64.0 (58.9–69.1) |

| Routine distribution‡ | 3.3 (2.3–4.3) |

| Commercial (social marketing)§ | 30.7 (25.8–35.7) |

| Private source¶ | 0.9 (0.5–1.3) |

| Not identified | 1.1 (0.5–1.6) |

LLIN = long-lasting insecticidal net; CI = confidence interval.

Refers to nets obtained free of charge from the October 2007 integrated campaign.

Refers to nets obtained free of charge from district health centers during antenatal clinics or routine vaccination visits.

Refers to nets purchased from boutiques, kiosks, or community-based distributors.

Refers to nets purchased from pharmacies, private health facilities, or private doctors.

Equity of LLIN ownership.

Post-campaign equity of LLIN ownership across economic quintiles was evident in the 59 districts (poorest quintile = 77.4%, 95% CI = 71.8–83.1%, wealthiest quintile = 73.5%, 95% CI = 67.7–79.3%, equity ratio = 1.05). The equity ratio for ownership of campaign nets was 1.48 (poorest quintile = 63.5%, 95% CI = 56.8–70.4%, wealthiest quintile = 42.9%, 95% CI = 35.3–50.5%), which indicated greater uptake by the poorest households. Equity of campaign net ownership was apparent among intermediate wealth quintiles; the ratio of ownership in the poorest quintile to ownership in the second (59.0%, 95% CI = 52.0–66.0%), third (57.3%, 95% = CI 50.9–63.6%), and fourth (62.1%, 95% CI = 55.4–68.8%) quintiles ranged from 1.02 to 1.11. In the 59 districts, ownership of nets from commercial sources favored the wealthiest, with an equity ratio of 0.64 (poorest quintile = 21.9%, 95% CI = 16.4–27.4%, wealthiest quintile = 34.2%, 95% CI = 28.8–39.5%). The equity ratio for free nets available through routine public health services in these districts was 0.78 (poorest quintile = 2.8%, 95% CI = 1.3–4.3%, wealthiest quintile = 3.6%, 95% CI = 1.0–6.3%).

LLIN use.

Post-campaign, 80.8% of all children less than five years of age and 68.5% of pregnant women reported sleeping under a LLIN from any source the previous night (Table 4). Use of LLINs by older children and adults was lower than use of LLINs by targeted groups. Older children were the least likely to sleep under a LLIN in households with ≥ 1 LLIN. In contrast, use of LLINs by children less than five years of age and pregnant women was 94.6% and 88.7%, respectively, if they slept in a household that owned ≥ 1 LLIN. In districts where LLINs were distributed during the integrated campaign, 59.9% of the total population slept under a LLIN the previous night (Table 4).

Table 4.

Use of any type of bed net and long-lasting insecticidal nets by different age/target groups in the 59 districts of Madagascar where LLINs were distributed during the October 2007 integrated campaign*

| Characteristic | Children < 6 months of age | Children < 5 years of age | Children 5–15 years of age | Adults | Pregnant women | Total population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 220 | 2,369 | 3,379 | 6,284 | 320 | 12,032 |

| % proportion use† (95% CI) | ||||||

| Any net | 84.3 (77.9–90.6) | 85.2 (82.2–88.2) | 57.2 (51.9–62.6) | 65.6 (61.8–69.5) | 77.6 (71.0–84.2) | 66.9 (63.2–70.6) |

| LLIN | 78.4 (70.8–86.0) | 80.8 (77.4–84.3) | 51.4 (46.4–56.5) | 56.9 (53.3–60.6) | 68.5 (60.2–76.9) | 59.9 (56.3–63.5) |

| LLIN (in HH with ≥ 1 LLIN) | 95.8 (90.8–100) | 94.6 (92.9–96.2) | 67.7 (63.4–72.0) | 78.6 (76.1–81.0) | 88.7 (83.0–94.4) | 78.8 (76.9–80.6) |

LLINs = long-lasting insecticidal nets; CI = confidence interval; HH = household.

Use = slept under net the night before.

Of children who were eligible to receive a net during the campaign (i.e., 6–65 months of age at the time of the survey) and who slept under a LLIN, more than 80% (83.4%, 95% CI = 80.0–86.7%) used a campaign net. In these districts, children born after the campaign (i.e., < 6 months of age at the time of the survey) who slept under a LLIN were also more likely to use a net from the campaign than nets from other sources, although the proportion of children was higher in districts where pregnant women were included in the targeted group for LLIN distribution during the campaign (80.5%, 95% CI = 71.7–89.2%) than in districts where LLINs were only targeted to children less than five years of age (58.3%, 95% CI = 44.8–71.8%) (P < 0.0001). Campaign nets were the principal source of nets used by pregnant women (72.2%, 95% CI = 64.0–80.4%), adults (65.4%, 95% CI = 60.0–70.7%), and older children (64.5%, 95% CI = 57.3–71.7%). The commercial sector constituted the secondary source of nets used by all age groups, ranging from 12.5% (95% CI = 9.5–15.4%) for children less than five years of age to 30.4% (95% CI = 25.3–35.5%) for adults, and nets from routine public health distribution channels and private sources constituted a small proportion of nets used by all age groups (< 4%), in accordance with low ownership of nets from these sources.

Malaria-endemic area.

In the 91 districts that comprise the malaria-endemic area of Madagascar, where LLIN distribution is part of the national malaria control strategy, 70.5% (95% CI = 66.3–74.7%) of households owned ≥ 1 LLIN and 27.2% (95% CI = 23.1–31.3%) of households owned ≥ 2 LLINs. Use of LLINs by children less than five years of age and by pregnant women was 74.5% (95% CI = 70.8–78.2%) and 62.2% (95% CI = 54.0–70.4%), respectively.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the significant achievement of ≥ 80% insecticide-treated net use among children less than five years of age after an integrated campaign that distributed free LLINs to children less than five years of age in 59 districts of Madagascar. Although LLIN use by pregnant women (69%) did not achieve the ≥ 80% level, it still represents one of the highest reported use rates for this target group in sub-Saharan Africa.28 The results of this study are similar to those in other countries where integrated campaigns have significantly increased LLIN ownership and use and improved equity.11,16 Importantly, the present study investigated total population LLIN use post-campaign, and suggests a contribution of targeted mass LLIN distribution to use by non-target groups. To avoid confounding effects related to different LLIN distribution methods and timelines in other areas of Madagascar, it was necessary to restrict our detailed analyses to the 59 districts with campaign net distribution.

The integrated campaign was the principal source of LLINs used by all age groups in districts where LLIN delivery was integrated during the campaign. Commercial nets, with a subsidized cost of US $1.5 or 3,000 ariary,23 represent a smaller proportion of nets in these districts and were the secondary source of nets used by all age groups. This finding is unlike the findings of Khatib and others 14 from a district of Tanzania with multiple net delivery strategies, where campaign nets were used predominantly by young children, and commercial nets were the main source of nets used by older children and adults. Multiple factors may potentially explain the larger contribution of the integrated campaign to net use in targeted districts of Madagascar: a shorter history of ITN social marketing in Madagascar (six years) compared with Tanzania (more than 10 years), different campaign distribution strategies including social mobilization, or different socioeconomic or environmental drivers of LLIN uptake.

The use of campaign nets by all household members in the present study is encouraging and suggests a contribution of free LLIN delivery through an integrated campaign to increased population level coverage in the targeted districts of Madagascar. Sharing of sleeping spaces and thus nets among household members, which is common in settings in Africa,11,21 effectively increases the proportion of the total population that is protected. Although the campaign contribution to population coverage is limited to households with children or pregnant women who are eligible to receive nets at the time of the campaign, this study shows that through a combination of delivery systems, including free mass distribution, commercial sector delivery, and routine free distribution through public health services, the post-campaign total population coverage in targeted districts reached nearly 60%. Killeen and others estimated that 35–65% coverage of entire malaria-endemic populations is needed to achieve community benefits through a mass effect on the vector population.4 Thus, in Madagascar, the rainy season rates of LLIN use observed in this study may have been sufficient to produce community benefits in addition to the personal protection provided to LLIN net users.

LLIN use was lower among children greater than five years of age and adolescents. Extensive use of LLINs among young children indicates protection for those most at risk for malaria morbidity and mortality, especially in areas highly endemic for malaria. However, children greater than five years of age are still vulnerable to severe illness and death from malaria, particularly in areas with seasonal or epidemic-prone malaria transmission where the development of partial immunity is slower.21 Fortunately, in the districts of Madagascar targeted for LLIN distribution during the campaign, the high population level coverage may afford communal protection to older children not sleeping under nets. A better understanding of the household dynamics of net use is needed to ascertain the determinants of net use by different age groups.

Use of LLINs by > 85% of target groups in households that owned ≥ 1 LLIN reflects the importance of increasing household ownership as a factor in increasing use. Furthermore, to maintain high levels of individual coverage and to enhance community-wide malaria reduction through coverage of non-target groups, delivery mechanisms that provide LLINs to children born between campaigns (e.g., routine public health distribution channels) and those that make LLINs available to households without target groups (e.g., social marketing) are still greatly needed. Distribution of LLINs to pregnant women appears to be an effective strategy to increase the proportion of infants sleeping under LLINs. Therefore, additional channels to distribute LLINs to pregnant women should be sought.

The integrated campaign was successful in reaching the poorest households. Lower ownership of campaign nets in the wealthiest households may reflect a reduced need for nets because of use of repellents and/or better constructed houses that reduce mosquito nuisance biting11 or the tendency not to use free delivery mechanisms and rely more heavily on the open market.14 The latter factor is supported by the economic disparity in ownership of nets from commercial sources. Cost was presumably a key limiting factor in the uptake of commercial sector nets by the poorest households. Low ownership of nets from routine public health services may reflect the more recent implementation of these distribution channels in western and southern Madagascar relative to social marketing. Poor access to health care or an insecure supply of nets may have also contributed to low uptake of nets through routine public health services by the most vulnerable groups. Additional studies are needed to better understand barriers to net ownership.

This study had several limitations. Because of flooding and road blockages caused by major cyclones that affected Madagascar in the months between the campaign and the survey, several areas were inaccessible to survey teams. Replacement of 13 of 120 fokontany might have reduced representativeness of the survey population, resulting in overestimation of LLIN ownership and/or use. This possibility would be particularly true if areas inaccessible during the survey had had reduced access to LLIN distribution during the campaign and therefore lower rates of ownership and/or use than accessible areas. The dry season timing of the campaign, when roads conditions are generally passable, reduces this potential effect of replacement on representativeness. Another potential limitation is recall bias by respondents with regards to source of nets in the household. To limit the potential bias effect, the LLIN brand observed in a given household was verified with the expected brands distributed during the campaign. Finally, extensive use rates for LLINs observed in this study, which was conducted near the end of the rainy season, will likely be affected by seasonality. High levels of LLIN hanging and use are common during the rainy season when mosquito densities are highest.29

The integrated campaign in Madagascar achieved high levels of LLIN ownership and use and reduced the apparent economic disparity in ownership of LLINs from other available sources. Furthermore, within the context of other LLIN distribution strategies in the targeted districts of Madagascar, the integrated campaign contributed to total population coverage by use of campaign nets by all age groups. Although it is not possible to make direct comparisons with the results of other integrated campaigns because of different population sizes, distribution methods, and baseline levels of net ownership, the results in Madagascar add to the body of evidence supporting integrated campaigns as an effective means of rapidly scaling up LLIN ownership and use.

Acknowledgments

We thank the families for participating in this survey; the survey teams for working under challenging field conditions; the many international partners for collaborating to successfully implement the integrated campaign and its evaluation; and Dr. Izaka Rabeson, Dr. Bary Rakototiana, and Fanja Ratsimbazafy (Madagascar Red Cross) for logistical and administrative support and supervision in the field.

Footnotes

Authors' addresses: Manisha A. Kulkarni and Peter Berti, HealthBridge, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, E-mails: mkulkarni@healthbridge.ca and pberti@healthbridge.ca. Jodi Vanden Eng, Annett Hoppe Cotte, and Adam Wolkon, National Center for Zoonotic, Vector-Borne, and Enteric Diseases, Division of Parasitic Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, E-mails: jev8@cdc.gov, cjn8@cdc.gov, and aow5@cdc.gov. Rachelle E. Desrochers, Department of Biology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, E-mail: rdesr104@uottawa.ca. James L. Goodson, Global Immunization Division, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, E-mail: jgoodson@cdc.gov. Adam Johnston and Marcy Erskine,Canadian Red Cross, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, E-mails: adam.johnston@redcross.ca and marcy.erskine@gmail.com. Andriamahefa Rakotoarisoa and Louise Ranaivo, Ministère de la Santé du Planning Familial et de la Protection Sociale de Madagascar, Service de Lutte Contre le Paludisme, Institut d'Hygiène, Antananarivo, Madagascar, E-mails: and@caramail.com and ranaivol22@yahoo.fr. Jason Peat, International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, Geneva, Switzerland, E-mail: jason.peat@ifrc.org.

References

- 1.Lengeler C. Insecticide-Treated Bed Nets and Curtains for Preventing Malaria (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gamble C, Ekwaru PJ, Garner P, ter Kuile FO. Insecticide-treated nets for the prevention of malaria in pregnancy: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maxwell CA, Msuya E, Sudi M, Njunwa KJ, Carneiro IA, Curtis CF. Effect of community-wide use of insecticide-treated nets for 3–4 years on malarial morbidity in Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7:1003–1008. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Killeen GF, Smith TA, Ferguson HM, Mshinda H, Abdulla S, Lengeler C, Kachur SP. Preventing childhood malaria in Africa by protecting adults from mosquitoes with insecticide-treated nets. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e229. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawley WA, Phillips-Howard PA, Ter Kuile FO, Terlouw DJ, Vulule JM, Ombok M, Nahlen BL, Gimnig JE, Kariuki SK, Kolczak MS, Hightower AW. Community-wide effects of permethrin-treated bed nets on child mortality and malaria morbidity in Western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68:121–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roll Back Malaria . Roll Back Malaria Global Strategic Plan 2005–2015. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.President's Malaria Initiative The US president's malaria initiative. Lancet. 2006;368:1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68939-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United Nations Development Program . Millenium Project. Final Report to United Nations Secretary General. London/Sterling, VA: United Nations; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roll Back Malaria . The Global Malaria Action Plan. The Roll Back Malaria Partnership. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisele T, Macintyre K, Yukich J, Ghebremeskel T. Interpreting household survey data intended to measure insecticide-treated bednet coverage: results from two surveys in Eritrea. Malar J. 2006;5:36. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-5-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grabowsky M, Nobiya T, Selanikio J. Sustained high coverage of insecticide-treated bednets through combined catch-up and keep-up strategies. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12:815–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noor AM, Amin AA, Akhwale WS, Snow RW. Increasing coverage and decreasing inequity in insecticide-treated bed net use among rural Kenyan children. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guyatt HL, Gotink MH, Ochola SA, Snow RW. Free bednets to pregnant women through antenatal clinics in Kenya: a cheap, simple and equitable approach to delivery. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7:409–420. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khatib R, Killeen G, Abdulla S, Kahigwa E, McElroy P, Gerrets R, Mshinda H, Mwita A, Kachur SP. Markets, voucher subsidies and free nets combine to achieve high bed net coverage in rural Tanzania. Malar J. 2008;7:98. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grabowsky M, Nobiya T, Ahun M, Donna R, Lengor M, Zimmerman D, Ladd H, Hoekstra E, Bello A, Baffoe-Wilmot A, Amofah G. Distributing insecticide-treated bednets during measles vaccination: a low-cost means of achieving high and equitable coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:195–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thwing J, Hochberg N, VandenEng J, Issifi S, Eliades MJ, Minkoulou E, Wolkon A, Gado H, Ibrahim O, Newman RD, Lama M. Insecticide-treated net ownership and usage in Niger after a nationwide integrated campaign. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:827–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stevens W, Wiseman V, Ortiz J, Chavasse D. The costs and effects of a nationwide insecticide-treated net programme: the case of Malawi. Malar J. 2005;4:22. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-4-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mueller D, Wiseman V, Bakusa D, Morgah K, Dare A, Tchamdja P. Cost-effectiveness analysis of insecticide-treated net distribution as part of the Togo Integrated Child Health Campaign. Malar J. 2008;7:73. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curtis CF, Maxwell C, Lemnge M, Kilama WL, Steketee RW, Hawley WA, Bergevin Y, Campbell CC, Sachs J, Teklehaimanot A, Ochola SA, Guyatt HL, Snow RW. Scaling-up coverage with insecticide-treated nets against malaria in Africa: who should pay? Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:304–307. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00612-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lines JD, Lengeler C, Cham K, de Savigny D, Chimumbwa J, Langi P, Carroll D, Mills A, Hanson K, Webster J, Lynch M, Addington W, Hill J, Rowland M, Worrall E, MacDonald M, Kilian A. Scaling-up and sustaining insecticide-treated net coverage. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:465–466. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00717-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teklehaimanot A, Sachs J, Curtis CF. Malaria control needs mass distribution of insecticidal bednets. Lancet. 2007;369:2143–2146. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60951-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Service de Lutte Contre le Paludisme . Plan Stratégique de Lutte Contre le Paludisme: du Contrôle vers l'Élimination du Paludisme à Madagascar 2007–2012. Antananarivo, Madagascar: Service de Lutte Contre le Paludisme, Ministère de la Santé du Planning Familial et de la Protection Sociale; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Population Services International . Madagascar (2006): Malaria TRaC Study Evaluating the Use of Insecticide Treated Nets among Pregnant Women and Mothers of Children Younger than Five Years. Antananarivo, Madagascar: Population Services International; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raveloson A, Benazerga W, Rakotondrajaona N, Ruebush T, Chang M, Cotte A, Thwing J, Greer G, Adeya G, Paluku C, Tuseo L, Renshaw M, Coulibaly I. President's Malaria Initiative Needs Assessment Madagascar. 2007. http://www.usaid.gov/mg/bkg%20docs/needs_assessment_report_2007.pdf March 18–30, 2007. Available at.

- 25.Institut National de la Statistique, Macro O . Macro O, Enquête Démographique et de Santé de Madagascar 2003–2004. Calverton, MD: Institut National de la Statistique and Opinion Research Corporation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Institut National de la Statistique . Recensement General de la Population et de l'Habitation. Antananarivo, Madagascar: Institut National de la Statistique; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vanden Eng JL, Wolkon A, Frolov AS, Terlouw DJ, Eliades MJ, Morgah K, Takpa V, Dare A, Sodahlon YK, Doumanou Y, Hawley WA, Hightower AW. Use of handheld computers with global positioning systems for probability sampling and data entry in household surveys. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:393–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization . World Malaria Report 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korenromp EL, Miller J, Cibulskis RE, Kabir Cham M, Alnwick D, Dye C. Monitoring mosquito net coverage for malaria control in Africa: possession vs. use by children under 5 years. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:693–703. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]