INTRODUCTION

The AACP Argus Commission is comprised of the five immediate past AACP presidents and is annually charged by the AACP President to examine one or more strategic questions related to pharmacy education often in the context of environmental scanning. Depending upon the specific charge, the President may appoint additional individuals to the Commission.

The 2008-09 Argus Commission was charged to examine the question of how colleges and schools of pharmacy are working to create agents of change for pharmacy and society. This charge was derived from the recommendation of the 2007-08 Argus Commission which stated that “the 2008-09 Commission, collaboratively with national student pharmacy leaders, should examine the curricular, co-curricular and extra-curricular strategies necessary for the development of change leadership for health care system improvement in student, faculty and alumni.”

AACP President Yanchick invited five national student pharmacist leaders to work with the Argus Commission for this discussion. Their views and voices contributed rich insight and recommendations for the Commission's work. All participants agreed that it was rewarding to link student pharmacist leaders’ perspectives from multiple schools and organizations with the thoughts of academic pharmacy's leaders in this unique gathering of the Argus Commission.

BACKGROUND

AACP is a liaison member organization in the Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners (JCPP), comprised of the major practitioner associations in pharmacy, and has participated actively in the strategic planning efforts JCPP has coordinated every five years since 1989. It was in 1989 that the profession's leaders declared that pharmacy needed a new mission and that the future of the profession depended upon a change in the focus of pharmacists’ practice from product distribution management to patient-centered care. The term pharmaceutical care was embraced by most in the profession at that time and has subsequently been modified to patient-centered care in keeping with terminology used by other disciplines and entities interested in health care reform and patient safety. The change in degree from the bachelors to the doctoral standard endorsed by the AACP House of Delegates in 1992 was based upon the agreement that this was the right direction for the profession for the 21st century.

In 1997, the AACP Janus Commission concluded its analysis of the need for change leadership in pharmacy by noting that “the future [of pharmaceutical education] is intimately and inextricably tied to the ability of its “product”, the pharmacist, to be a pharmaceutical care provider and team member within an integrated and intensively managed system of health care delivery. A truly effective and sustained partnership between pharmaceutical education and pharmacy practice has never been more critical to our collective success.”1

While many will acknowledge that progress has been made and that some pharmacists across all practice settings have embraced patient-centered pharmacy practice, overall insufficient progress has been made. Across the country there are pockets of excellence in pharmacy that are identifiable and these have been profiled in numerous programs and publications. Some research and demonstration projects provide concrete evidence of the impact of pharmacists’ services on positive patient outcomes and citations can be found in the pharmacy and medical literature. The Argus Commission acknowledged, however, that the majority of pharmacists do not dedicate a meaningful portion of their practice to patient care aimed at ensuring that patients’ achieve the intended outcomes from medication use and avoid harm. The need for accelerated practice change is directly tied to the need for expanded leadership contributions from all pharmacists at every level of practice and administration, including those in academia.

Ross Tsuyuki and Theresa Schindel, principals in the Centre for Community Pharmacy Research and Interdisciplinary Strategies at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada, published a monograph on Leading Change in Pharmacy Practice in December 2004.2 They utilized Kotter's framework for change to outline the steps needed to be undertaken by pharmacists and pharmacy's leaders to achieve the envisioned change. Leadership for change in pharmacy practice is essential and the Argus Commission sets forth an argument that pharmacy education must join forces with practice leaders to stimulate and support the efforts of frontline pharmacists and state and national leaders to fully activate the necessary change in pharmacists’ patient care activities. The schools have a specific responsibility in creating leaders as agents of change among those pursuing a degree in pharmacy.

Certainly this is not the first time an AACP committee has examined the question of leadership development in pharmacy education. President Barbara Wells charged several standing committees with examining varied aspects of academic pharmacy's needs for leadership in 2002-03 and the recommendation to create a Center for Academic Leadership and Management from their work has been implemented.3 AACP has been actively engaged in leadership development through programming targeting future academic leaders (e.g., Academic Leaders Fellowship Program) and regular programming for deans and other pharmacy education administrators. By July 2009 almost 150 fellows will have completed the ALFP program and more than 100 CEO deans have been engaged in this program as mentors and facilitators. Several fellows have assumed academic leadership positions, including four who now serve as deans of colleges of pharmacy.

With regard to student leaders, most recently the 1999-2000 Professional Affairs Committee4 was charged to “explore issues related to the promotion and development of leadership in pharmacy students as part of the professional curriculum” and develop a list of strategies to establish or enhance leadership programming in both the curricular and extracurricular contexts. The substance and recommendations of this report and the report of the 1995-96 Professional Affairs Committee5 which sought to identify strategies for predicting and developing leadership potential among students, graduate students and residents remain timely and useful for those interested in enriching leadership development activities at colleges and schools of pharmacy.

Retirements will create gaping holes in leadership across all sectors of pharmacy over the next decade. It was estimated by Sara White in 2005 that 80 percent of those currently serving as health systems pharmacy directors will retire within the next 10 years with 36% staying less than five years.6 This led to the establishment of the Center for Health System Pharmacy Leadership within the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists Foundation. Organizations of all types wonder where the next generation of capable leaders will be found.

Notwithstanding many efforts to enrich the leadership of academic pharmacy, it is apparent to many that our efforts, along with those of other associations and organizations in pharmacy, have been insufficient to create in our profession a cadre of practitioners, scientists, and educators with the skills and motivation to create long-called-for-change in the profession and health care system. The “elephant in the room” is that the practice of pharmacy in many settings remains far from the vision called for universally by pharmacy leaders. Most pharmacists on the frontlines of health care still allocate their time to prescription or medication order processing and claims adjudication, activities more appropriate for well trained and supervised technicians. Pharmacists’ leadership of medication use is largely unrecognized beyond the profession's boundaries. As a result, patients suffer avoidable harm from insufficient access to medications and/or inappropriately prescribed and managed drug therapy.

Leadership for the improvement of medication use and pharmacy practice change is sorely needed. Some would argue that it is inappropriate to place this expectation of leading the way to new practices and change implementation upon our current graduates, the newest members of the profession. Yet they are the pharmacists with the clinical skills to practice patient-centered care and the most motivated to practice as they were taught, notwithstanding the fact that they are not often in control of all aspects of their practice environment. Therefore, it is imperative that we also educate them to lead change as non-positional leaders.

AACP is not alone in this recognition. A task force of student and new practitioner members convened by the leadership center of the ASHP Foundation issued a report earlier this year analyzing a perceived “pharmacy leadership gap.” “Leadership as a Professional Obligation”7 summarized the situation of insufficient leadership skills among graduates and practicing pharmacists to enable achievement of ASHP's Vision 2015 and set forth several recommendations, including one calling upon colleges and schools of pharmacy to provide leadership training to all students in a standardized fashion.

Building on a 40-year tradition of student activism and leadership development, the presidential theme of Brent Reed, 2008-09 national President of the APhA-Academy of Student Pharmacists is “It Starts with One: Empowering Students as Agents of Change”. Through educational programs at the local, regional, and national levels as well as articles, podcasts and a regional challenge to develop innovative strategies to ignite leadership development, APhA-ASP calls upon its members to recognize their individual and collective potential to be the change agents for pharmacy's future contributions to quality patient care.

The annual Pruitt-Schutte Business Plan competition coordinated by the National Community Pharmacists Association is an excellent example of a program designed to stimulate interest in entrepreneurial leadership among students. In some programs it is extracurricular and in other schools business plan development and the competition has been incorporated into a course. Similarly, the Student National Pharmaceutical Association theme for the current year is “Strengthening the Diversity, Approaching Health Disparities”. Chapters have been encouraged to develop projects targeting care to underserved populations as an outstanding opportunity to build leadership skills for future practice change among PharmD students.

It is against this backdrop of perceived need for more sustainable leadership development efforts despite the existence of many excellent programs that a fresh examination of the role of colleges and schools in leadership development was undertaken. As this report was being written a new US president began his term and he, along with leaders in Congress, signaled that health care reform would be among the top domestic priorities for the 111th Congress. Without sufficient leadership from pharmacy, real solutions to better health care which are so dependent on the more rational and effective use of medications and pharmacists’ services will not be realized. AACP and other pharmacy organizations must feel a sense of urgency to contribute to the development of policies on health care delivery, financing and the health professions workforce.

LEADERSHIP IS A RESPONSIBILITY FOR ALL

What is the most appropriate philosophy of leadership for pharmacy practice and education in the 21st century? The Commission quickly determined that they favored the philosophy that everyone has the potential to contribute leadership in the profession and society, and this belief extends to all student pharmacists, faculty and alumni. Consensus was also achieved that a breakthrough is needed to build a sustainable system of leadership development for pharmacy education and practice. It became clear through the discussions that the requirements for a sustainable system include the following elements:

Supportive institutional culture

Admissions considerations

Alumni and faculty role models

Administrative and financial support

Co-curricular thread of courses and activities

Postgraduate education and training opportunities

The students noted that a number of issues, in large measure attitudinal, serve as obstacles to activating leadership among many current Pharm.D. students. Students may falsely assume that their pathway to opportunities to practice patient-centered care is well established and obstacle free. In addition, there are misconceptions that leadership is synonymous with management. Students will say “I just want to use my clinical skills to take care of patients. I don't want to be a manager. I'm not a leader.” Further, many students resist invitations to take active roles in extracurricular projects and committees or seek elected leadership positions in student pharmacist organizations out of concern that it will detract from their studies or their work responsibilities. These are important perceptions that cannot be dismissed in considering reinvigorated approaches to leadership development at colleges and schools of pharmacy.

The concepts articulated by Sara White in the 2006 Harvey A.K. Whitney Award Lecture8 resonated with the Commission. She noted that there is a need for two distinct types of leadership. “Big L” leaders are those individuals in formal leadership positions, such as directors, supervisors, clinical coordinators and those in elected positions in organizations. They are a small portion of all pharmacy practitioners. However, all pharmacists must view themselves as “little l” leaders and recognize that every day on every shift in their pharmacy practice they have leadership opportunities and responsibilities in their work with patients, pharmacy personnel, other health care professionals and with administrators in the practice environment. Leadership of medication use improvement will largely depend on the activation of this type of leadership by every pharmacist, and especially frontline care providers, in every setting every day.

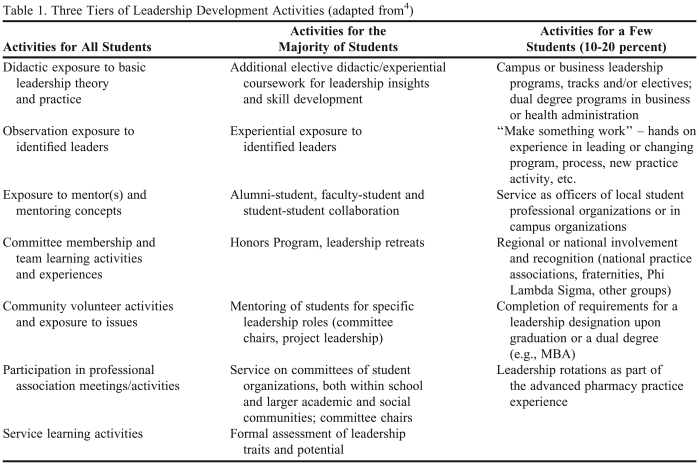

The Commission reviewed and updated a tiered model for leadership development for pharmacy education beginning with the table published in the 1999-2000 Professional Affairs Committee report. As noted in Table I there are three levels of student leadership development activity with activities for all students, activities for the majority of students and then activities for a smaller subset of students. In the right culture of leadership, the majority of students should engage in leadership development activities and coursework beyond that which is minimally required. The third group would tend to be those individuals who seek additional formal preparation for positions of leadership through dual degree programs or tracks. These are also those individuals who make excellent national student leaders such as those serving with the Argus Commission in the development of this report (Table 1).

Table 1.

Three Tiers of Leadership Development Activities (adapted from4)

THREADING LEADERSHIP THROUGHOUT PHARMACY EDUCATION

Members of the Commission provided summaries of different models of leadership development currently in use at their institutions, including several courses and multiple-unit concentrations leading to leadership certificates or degree designations. Two models submitted pursuant to a call for successful practices are summarized in Appendix A.

It was the consensus of the Commission that significant progress in stimulating new leadership for the profession will require a co-curricular concentration of developmental activities purposefully threaded throughout the Pharm.D. program. Such programs would include the many extra-curricular opportunities available through student organizations (both college and campus based) and embedded in community service activities.

To be successful, an expectation for leadership development must be central to the culture of the college or school of pharmacy. This begins with the dean and the dean's administrative team and must include all faculty members. As noted by the AACP Janus Commission, colleges and schools have a responsibility to collaborate with the profession's practice leaders to advance the delivery of patient-centered (pharmaceutical) care services in all settings. This should be reflected in the school's mission and culture. As will be noted in the section describing five key practices for student leadership development, a commitment to leadership must be modeled by all of those with whom students are in contact. The philosophy that all students have a responsibility to prepare to serve as agents of change in practice must be embraced by the faculty, administrators and preceptors who facilitate their learning and development.

The students acknowledged the importance of the deans and faculty in creating an environment where students’ active engagement in leadership is encouraged and supported. Policies clearly supporting student participation in local projects (e.g., health fairs, service to underserved populations) and attendance at regional and national meetings were noted as essential components of a healthy leadership development culture. Such support would include both financial assistance for travel and appropriate recognition of the need for time away from classes/rotations to participate in these activities. The students emphasized the critical role of well-prepared and committed organizational advisors to the success of student organizations and leadership development activities. Deans also have the opportunity and responsibility to create an understanding of and expectation for change in pharmacy practice among those in upper administration positions (e.g., Vice Presidents of Health Sciences, Provosts, Presidents, Trustees), most of whom will not be knowledgeable about the significant benefits of such change.

Faculty members also have an important role to play as translational scholars. Many faculty members are innovators of advanced patient care practice models in many settings and have incentives to assess the impact of their services on patient outcomes. Their ability to bring that experience into their teaching, whether in the classroom or the patient care setting, and inspire the replication of their work by their students, adjunct faculty and alumni is critically important.

It was noted by the student leaders that many faculty appear to be “saturated” in terms of managing their current teaching, research and service responsibilities. Often the work of mentoring individual students and advising organizations is layered on top of other work priorities. It is essential that faculty position descriptions and evaluation systems place appropriate emphasis on faculty leadership development activities, including the mentoring of leadership capabilities in students both in and out of the context of organizational activities. Sharing models of organizational advising, leader mentoring and small workgroup facilitation with faculty members and administrators would enhance their ability to produce additional leadership skills among students.

The current pharmacy education model offers numerous opportunities to introduce and build leadership skills in our students, beginning at the point of the admissions process and orientation. It includes teamwork skills developed for both curricular and extracurricular projects, cases and activities. APhA-ASP patient care projects, community service activities and competitions such as the interprofessional Clarion Project originated by the University of Minnesota, the ASHP Clinical Skills Competition or the NCPA Business Plan competition all offer leadership skill development opportunities.

It is important to note that there was some controversy with regard to leadership as an admissions issue. Should the admissions process include approaches that seek to identify those candidates with leadership potential to preferentially admit to our programs? Does the demonstration of past leadership contributions or a particular profile on a leadership assessment tool indicate greater potential to demonstrate leadership while in school and after graduation? These were questions the Argus Commission could not easily answer, yet they were firm in their belief that there is a role for placing some level of emphasis on identification of leadership potential as a function of the admissions process. It is important to note that the Association of American Medical Colleges has embarked upon a new study, called “holistic admissions assessment”, with an aim of identifying admissions parameters that facilitate the identification of a diverse medical student body, including students with leadership potential. AACP will monitor their discussions closely and consider whether their findings are relevant to the pharmacy admissions process. This is a fruitful area for educational research as well.

Similarly, the responsibility of the colleges and schools to the continued professional development of graduates, including their leadership capabilities, provoked discussion. AACP is on record strongly encouraging colleges and schools to provide leadership in the development of postgraduate education and training programs that can accelerate acquisition and maturation of a variety of leadership skills. This includes equipping graduates to lead practice change through residencies and fostering other leadership roles in science or administration nurtured through graduate education.

There is a win-win proposition related to stimulating leadership for practice change in all settings when considering today's pressure to ensure sufficient numbers of sites for quality experiential education. Equipping our students and future preceptors with the ability to be change agents in their practices and supporting their continuous development as alumni should have the beneficial effect of increasing the capacity for both introductory and advanced pharmacy practice experiences.

A FRAMEWORK FOR STUDENT LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT

There are dozens of leadership theories and thousands of books and articles on the topic. A new and timely contribution to the literature titled The Student Leadership Challenge: Five Practices for Exemplary Leaders 9 was released by authors James Kouzes and Barry Posner just prior to the meeting of the Argus Commission. The book provided a useful framework for specific strategies and recommendations identified by the Commission as important for building a sustainable approach to leadership development by AACP member institutions and other key stakeholders.

The five practices are:

Model the Way

Inspire a Shared Vision

Challenge the Process

Enable Others to Act

Encourage the Heart

The authors emphasize the philosophy that leadership truly is for all. Citing from the text (page 2), “The domain of leaders is the future, and leadership is not the private reserve of a few charismatic men and women. It is a process ordinary people use when they are bringing forth the best from themselves and others. When the leader in everyone is liberated, extraordinary things happen.”

Each of the five practices will be introduced followed by reflections from the Argus Commission related to their tactical application with student pharmacists and pharmacy practice leadership development.

Model the Way

Faculty, administrators, students in organizational or class leadership, and practice leaders must model the behaviors they expect of future pharmacists as agents of change. Further, leaders must be clear about their own guiding principles and values and make them obvious to others through their actions. “Modeling the Way is about earning the right and the respect to lead through direct involvement and action.” (Kouzes and Posner, page 12)

The Argus Commission identified the importance of such role modeling beginning with the deans and extending throughout the faculty. Strong organizational advisors and the previously noted support, both financial and operational, for students’ active participation in association and related activities are essential. The schools can make the leadership roles faculty and alumni assume more visible to students in a variety of ways, encouraging these leaders to tell their stories of both Big L and Little l leadership contributions. It is particularly important for students to be exposed to pharmacists modeling patient-centered care delivery in all settings. Role model practitioners can be brought in to classes or organizational meetings and should certainly be involved in experiential education at all levels. Science faculty from all disciplines can play key roles in emphasizing the importance of basic and applied science in the contemporary practice of patient-centered care that is evidence based and personalized to meet individual needs.

Inspire a Shared Vision

Leaders have visions and dreams of what could be. Certainly pharmacy's leaders can articulate a vision of making pharmaceutical care the standard of practice for patient care in all settings of practice. True leaders must inspire a shared vision with those they are asking to follow and lend support to projects that aim to close the gap between today's reality and that vision. “Student leaders breathe life into the hopes and dreams of others and enable them to see the exciting possibilities that the future holds. They forge a unity of purpose by showing constituents how the dream is for the common good. Leaders stir the fire of passion in others by expressing enthusiasm for the compelling vision of the group.” (Kouzes and Posner, page 140)

No one would argue that we have many student leaders at the local, national and even international levels who have embraced the vision for patient-centered pharmacy practice. They express their commitment verbally in many forums but more importantly they model it through the outstanding efforts they direct to patient care projects, advocacy and outreach in many forms. However this appears insufficient to sustain their commitment as change agents upon graduation and to stimulate similar action among their peers by inspiring a shared vision that is sustainable.

The Argus Commission spent substantial time discussing “the elephant in the room” with respect to inspiring current and future pharmacists with the leadership vision and commitment to lead practice change. While every school has the potential to show students exemplary practices of faculty and leading preceptors, the reality is that there is a significant disconnect between the vision for pharmacy's future and the average practice in any setting of pharmacy today. Unfortunately, this may even be the case in some of the settings where students are placed for introductory and advanced pharmacy practice experiences. For many students, especially those with experience as technicians and interns in traditional practice settings, there is a credibility gap between what faculty and practice leaders express as the vision for pharmacy and the current standard of pharmacy practice in 2009.

This is the profession's Achilles Heel. In large measure the profession's leaders have been unable to inspire the majority of frontline practitioners and midlevel managers from all practice settings to become the agents of change to transition pharmacy from its primary focus on drug distribution to the sorely needed model of safer and more effective medication use.

AACP's Commission to Implement Change in Pharmacy Education10 asserted that society needed pharmacists to assume such responsibility in future health care delivery systems. This vision led to the doctoral level education requirement for all pharmacy graduates. The accreditation standards since the turn of the century have emphasized patient-centered pharmaceutical care and now embrace the core competencies for all health care practitioners espoused by the Institute of Medicine. It becomes clear, however, that changes in both our education and practice are required to achieve a shared vision for the future embraced by both our organizational and practice leaders in pharmacy.

Challenge the Process

Leadership requires a departure from the status quo. Leaders are pioneers who constantly look for opportunities to innovate, grow and improve. In the words of the Millis Commission, pharmacy leaders must be infected with “divine discontent” with pharmacy and health care as it exists today and be willing to apply their unique knowledge, skills and ability to address unmet health care needs of our patients and society.11

The Argus Commission agreed that our co-curricular emphasis on leadership development aims to equip students with an expectation that they must challenge the status quo. Several essential skill sets were noted. The ability to assess a practice situation and analyze how improvements could be introduced, tested and refined are essential skills consistent with systems thinking and quality improvement core competencies. Promoting participation in efforts such as the NCPA Business Plan Competition formalize the knowledge and skills students need to be innovative and entrepreneurial as they learn the essentials of opportunity identification and business planning.

Our experiential education programs are burdened with many expectations, often exceeding the resources directed to achieving program aims. However, even the earliest practice exposure through Introductory Pharmacy Practice Experiences can be used to develop students' analytical ability to identify a process that could benefit from change and begin the creative thinking processes to envision the steps leading to the introduction of a practice improvement in that setting. Ultimately the Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences should expose students to exemplary care environments and practice role models who challenge our students to apply their vast knowledge of medications and appropriate therapeutics to the care of actual patients. Overall, our experiential education programs should advance students’ appreciation of their responsibility and potential to change their future practice environments. The colleges and schools can create a win-win situation with preceptors and the experiential education sites that accept students by systematically enabling them to advance their practices toward the vision of patient-centered care.

Enable Others to Act

“Grand dreams don't become significant realities through the actions of a single person. It requires a team effort. It requires solid trust and strong relationships. It requires deep competence and cool confidence. It requires group collaboration and individual accountability. To get extraordinary things done in organizations, student leaders have to enable others to act.” (Kouzes and Posner, page 17).

Perhaps the most essential skills to inculcate in our student leaders are the ability to foster collaboration, delegate and strengthen others to contribute to the achievement of the project aims. Too often, especially in our student led organizations, our leaders fail to activate others and risk burnout and failure. Faculty burnout is similarly an important issue to consider when examining student and practitioner leadership skill development.

Perhaps we depend too much on our extra-curricular opportunities, assuming students will acquire these skills through organizational activities, and fail to incorporate them sufficiently into didactic, laboratory and experiential education.

The ability to organize and lead teams and participate on effective teams are learned skills consistent with the need for team-delivered patient care and organizational effectiveness. The Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ) and Department of Defense have developed a program called “TEAM STEPPS”, which is an evidence-based teamwork system aimed at optimizing patient outcomes by improving communication and other teamwork skills among health care professionals. It includes a comprehensive set of ready-to-use materials and training curricula necessary to integrate teamwork principles successfully into your health care system.12 A multimedia train-the-trainer program is available for use by educators and health systems leaders and AACP is exploring options for making these resources visible and accessible for use by pharmacy faculty in partnership with other health disciplines.

The Argus Commission discussed how insights into personal strengths and other characteristics can help all participants on a team function more effectively. The Myers Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), Clifton Strengths-Finder™, and Kouzes and Posner's own Student Leadership Practices Inventory are examples of various tools that can be used with students to identify their unique leadership styles.

There was also a discussion about the many real impediments to effective engagement of the majority of students in projects and organizational change activities. Cynicism, fear of too little time, academic overload, family and work demands are all real personal issues. These can be addressed in a variety of ways, including direct and indirect financial and other support mechanisms. Inadequate planning of projects, insufficient advising support and lack of essential skills development for student leaders are correctable issues if the institution has the right level of commitment to activating student engagement.

Colleges and schools should examine their experiential education programs to specifically identify additional opportunities to have students and preceptors partner on practice innovation and leadership development activities. Allowing students to lay the groundwork for in-store screening activities or immunization clinics in pharmacies while on rotation are simple examples, as is having students in hospital and other rotations advance the process of medication reconciliation in those institutions.

Encourage the Heart

Challenging the status quo and implementing change is hard work. “It's part of the leader's job to show appreciation for people's contributions and to create a culture of celebrating values and victories. Celebrations and rituals, when done with authenticity and from the heart, build a strong sense of collective identity and community spirit that can carry a group through turbulent and difficult moments.” (Kouzes and Posner, page 20-21).

One of the greatest values of teaching effective teamwork as a core value and essential skill set in today's student pharmacists is that it creates an expectation that no one can achieve anything significant alone and that the team depends on the contributions of every member. Generational shifts in our student population trend naturally toward a decreased sense of individualism and toward collaboration. That said, there is a need to recognize both individual and team success in visible and tangible ways.

Service learning is an essential component of leadership development. Such activities underscore the idea that service to others and seeing and understanding the needs of others motivates leadership. The first step of leadership of change is seeing how things could be better and students need to find those motivators for themselves - to develop a heart, to answer the question “how can I better serve my patients and my community?”

It is important for academic administrators and student leaders to learn effective strategies for celebrating success and recognizing achievements at multiple levels. Verbal and written expressions of thanks are equally important as formal awards and honors. Certainly organizational support from faculty, administration and other students goes a long way to encourage continued participation and hopefully will stimulate greater levels of participation from the whole student body.

The Argus Commission also reinforced the importance of leaders taking care of themselves to avoid burnout and academic distress. Showing others how fun it is to engage in leadership activities and accomplish projects is highly motivating.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Building a sustainable program of leadership development to activate agents of change in pharmacy is a complex proposition. As noted throughout the report it requires a supportive institutional culture as well as clear support from the top administrators, strong faculty and practitioner role models, and essential skills development. The responsibility for pharmacy educators begins with attracting the right types of individuals to study pharmacy, threading leadership expectations and skills development throughout the curriculum, providing numerous opportunities for students to engage and further develop their leadership skills and celebrating our successes. It is clear that the schools, in partnership with the profession's state and national practice organizations, must continue to support graduates’ leadership development through post-graduate training and education programs and attention to the continuous professional development of pharmacists in all settings.

Our society has recognized that the health care delivery system that has evolved in America is broken and financially unsustainable. The safe and effective use of medications and expanding access to primary care resources to coordinate care and coach patients to be knowledgeable and responsible participants in well-managed models of care are two essential ingredients in health care reform for both the public and private sectors. Pharmacists, pharmacy faculty, and student pharmacists can be highly effective agents of change, bringing creative thinking to address the very real problems of access, quality and affordability of health care.

The Argus Commission was reminded that “responsibility” is the willingness and commitment not just to find problems but to commit the energy to identify solutions and work to implement them. The year 2015 is now only slightly more than five years away and there seems to be the will in 2009-2010 to tackle the intractable problems of health system delivery and payment reform. The need to develop leaders at all levels of pharmacy practice has never been more timely or vital to the future of the profession and the health of the patients our graduates serve.

With this recognition the following statements of policy are proposed and recommendations made:

Policy Statement #1

Administrators, faculty and students at all colleges and schools of pharmacy share responsibility for stimulating change in pharmacy practice consistent with the Vision for Pharmacy in 2015 developed by the Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners.

Policy Statement #2

Curricular modifications should occur such that competencies for leading change in pharmacy and health care are developed in all student pharmacists, using a consistent thread of didactic, experiential and co-curricular learning opportunities.

Policy Statement #3

Expectations for faculty to provide leadership in pharmacy and health care must be supported with appropriate faculty development, mentoring and reward systems.

Recommendation #1

AACP should include student members as potential appointees for relevant standing committees, working groups and task forces.

Recommendation #2

AACP should encourage the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education to strengthen the emphasis on leadership development in relevant curricular and co-curricular standards and guidelines.

Recommendation #3

Schools and Colleges of Pharmacy, with the assistance of AACP in developing assessment tools, should incorporate an assessment of leadership potential into their admissions processes.

Recommendation #4

AACP and member colleges and schools should increase efforts to foster collaboration between institutions and pharmacy practice organizations, especially at the state level.

Recommendation #4

AACP should encourage the ASHP Commission on Credentialing to further strengthen residency program standards related to leadership development.

Recommendation #5

Schools and Colleges of Pharmacy should engage the professional community as to their needs for leadership training and develop post-graduate training and education programs to advance leadership skill development among professionals.

Recommendation #6

AACP should partner with other interested organizations to develop a toolkit of resources to assist colleges and schools of pharmacy in their efforts to strengthen the emphasis on leadership in curricular, co-curricular and extra-curricular programs.

Appendix A.

Successful Practices in Student Leadership Development

Curricular and Co-curricular Strategies for Leadership Skill Development and Unique Extra-curricular Activities to Promote Practice Change Leadership among Students, Faculty and Preceptors Submitted by the University of Minnesota and University of Pittsburgh

University of Minnesota

College of Pharmacy

Duluth, MN 55812

Student Leadership Development

Area of Best Practice: Curricular and Co-Curricular Strategies for Leadership Skill Development

Description

Overview.

The University of Minnesota offers two, two-credit elective introductory leadership courses to student pharmacists on both our Twin Cities and Duluth campuses. These courses cover foundational concepts and skills in leadership to prepare students for elected/appointed positions and non-positional leadership. Students may choose to further and foster their leadership knowledge and skills through completion of the College's Leadership Emphasis Area. Graduates completing this area participate in an additional 14 credits of coursework that includes didactic, experiential and self-directed learning. Upon completion of the emphasis area, students will graduate with a special transcript notation.

The aim of the introductory leadership course series is to foster knowledge of self though discovery of strengths, examination of current leadership practices, and awareness of emotional intelligence. Students focus on the leader's role through discussions of leadership vs. management, practices of an exemplary leader, the change process, the leader's role in change and harnessing of emotions. Actions and skills of leadership are practiced through team building exercises, visioning, networking, creative communication, and navigating Kotter's eight steps of leading change. Concepts related to committing to excellence are fostered through an overnight retreat that is required for students enrolled in the fall course offering and optional for any interested second through fourth year students in the college.

The emphasis area builds upon the introductory series through elective courses in management, a management/leadership advanced pharmacy practice experience, and an online book club that explores additional leadership theory and concepts. Further, self-directed learning activities offer opportunities for students to reflect on their leadership development, participate in professional leadership activities, and lead and report on a self-identified change project.

Program Structure.

Introductory course and emphasis area directors are located on each campus. The Assistant Dean for Educational Development serves as a third member of the leadership curriculum team. Four hours of administrative staff support is available weekly. This team is responsible for the introductory course series and student navigation though the emphasis area. Additional instructors include pharmacists outside the college recognized for their leadership. These pharmacists are matched with students to form Leadership Network Partner teams. The teams meet twice each semester for structured and unstructured learning activities. All teams gather together on campus twice per semester for large group learning sessions focused on course topics. Advanced pharmacy practice experience preceptors coordinate their practice experience with concepts discussed in the course series through weekly structured site activities.

Financial Support.

A Student Leadership Programming Development Fund was made available by a gift from Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. The fund provides support for the fall leadership retreat, leadership partner network meetings, and the acquisition of some of the learning materials used in the course.

Outcomes

Though just approved for offering in December 2007, the introductory course series and emphasis area has produced the following outcomes:

Over 50 students have participated in at least one of the introductory leadership courses.

Over 90 students have participated in the two offerings of the Fall Leadership Retreat and reported positive changes in their perceptions of leadership and ability to lead change. Opportunities to build relationships with colleagues and engage in self-reflection are cited as the most valuable retreat aspects.

Students self-report a stronger awareness of their strengths because of the course.

Students and leaders in practice report mutual benefit from the leadership network partner program.

Eleven students enrolled in the leadership emphasis area in the first year of availability with ten completing the program in 2009.

Leading change projects lead by students have addressed curricular issues, intern program improvements, MTM practice development, improvements in patient health literacy, initiation of pharmacist services in an emergency department and initiation of immunization services.

Barriers to Implementation.

Few barriers to implementation have been encountered in the development and initial offerings of the course and emphasis area. However, difficulties could be encountered if adequate staff and faculty are lacking to manage the course. Because the course series is elective, classroom content and experiences are not currently available to all students. Faculty support for a leadership curriculum may be difficult without an understanding of leadership principles and agreement of course intent.

Advice/Lessons Learned.

Faculty familiarity with appropriate leadership references and the application of their principles to pharmacy is of the utmost importance. Communication with faculty regarding the intent and purpose of design for a leadership curriculum is paramount for approval. Partnership with the practice community is extremely valuable in providing “real world” context for leadership. A combination of didactic, experiential and self-directed learning is required to reinforce and apply course principles.

Contact: Andrew P. Traynor, PharmD, BCPS, Assistant Professor and Assistant Director, Ambulatory Care Residency Program, 215 Life Science, 1110 Kirby Drive, Duluth, MN 55812.

Tel: 218-726-6027. E-mail: tray0015@umn.edu

http://leadership.pharmacy.umn.edu/Emerging/Emerging%20Leadership.html

University of Pittsburgh

School of Pharmacy

Pittsburgh, PA 15261

Student Leadership Development

Area of Best Practice: Preparation for and Success in Academic Careers in Pharmacy

Description

Pharmacists are increasingly relied upon to assume leadership roles in patient care and health care organizations. Regardless of their title or formal position in the organization, pharmacists will have the opportunity to lead and set the direction. Additionally, students were expressing an increasing interest in pharmacy leadership and management. As a result, the University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy designed a comprehensive series of progressive curricular leadership offerings for students.

The program was designed to provide a structured learning opportunity which was packaged into tiers with an increasing level of concentration depending on the interest and commitment of the student.

Tier 0: Integrated Curriculum.

The default tier for the management content was built directly into the existing Pharm.D. curriculum. An Ad Hoc Task Force was formed and a gap analysis was performed of all existing management-related content within the current curriculum. Based on the results of the gap analysis, comparison with the ACPE requirements, and the recommendations of the Task Force members, content was added. Additional lecture and practicum content was added to Profession of Pharmacy courses (1, 2, 4) and the Experiential Learning courses (5 and 6). This resulted in an additional 31 hours of management content added to the curriculum (in addition to the existing content). Subsequently, all pharmacy students received instruction in basic management areas necessary to manage themselves, their role in organizations, and their role in the profession.

Tier 1: Elective Coursework.

Those students that developed an interest in leadership and management, could then elect to progress further by selecting elective content in pharmacy administration in a variety of 10 courses which were created within the school of pharmacy. Approved School of Pharmacy courses include:

Pharmacy Administration 1, 2, 3 & 4 (PHARM 5900-03) - 2 Cr each

Executive Board Room Series 1 (PHARM 2510/BIND 2510) - 1 Cr

Executive Board Room Series 2 (PHARM 2511/BIND 2511) - 1 Cr

Concepts of Managed Care Pharmacy, (PHARM 5815) - 2 Cr

Community Pharmacy Management (PHARM 5805) – 3 Cr

Improving Health care Innovation (PHARM 5812) 1 Cr

Special Projects (PHARM 5800) 1-3 Cr

This allowed students to explore this interest area further without a significant commitment.

Tier 2: Area of Concentration.

Students interested in a more formal commitment to pharmacy leadership and management learning can apply for admission into a newly created Area of Concentration in Pharmacy Business Administration (AOC-PBA).

The primary objective of the area of concentration is to provide a more comprehensive exposure to key elements of leadership and administration. The AOC-PBA is not intended to provide all of the necessary training needed to become an effective leader, but rather expose students to an area of pharmacy practice that may best suit their interests. It is the intent that student leaders and informal organizers may discover that pharmacy leadership provides an energizing career path. Students are required to complete 6 hours of pharmacy management didactic content, two pharmacy management rotations from an approved list of experiential offerings, and one supervised management project for credit. Upon successful completion, students receive special acknowledgement of their area of concentration on their official university transcript.

Tier 3: Graduate Degree & Residency.

Upon completion of the AOC-PBA, students interested in exploring additional management training can receive advanced standing (credit for coursework already completed) in the Master of Science Degree in Pharmacy Administration (School of Pharmacy), the Master of Public Health with an emphasis in Pharmacy Administration (Graduate School of Public Health) or the Master of Business Administration (Joseph M. Katz Graduate School of Business).

Students pursuing the MS or MPH may also apply to the two-year pharmacy practice management residency in Hospital Pharmacy Administration at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center or the community pharmacy practice management residency in Pharmacy Administration through the University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy & CVS thereby completing the residency and degree program concurrently.

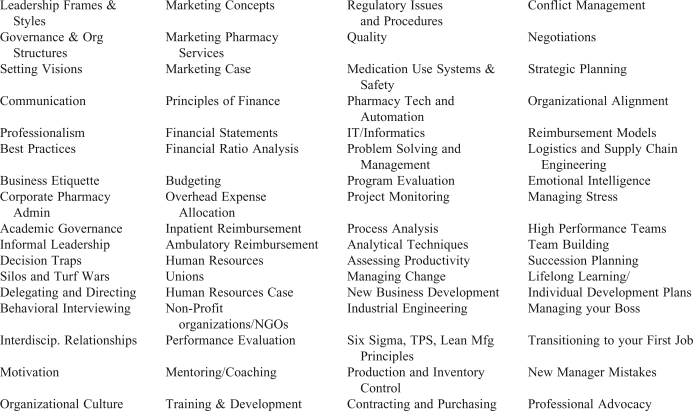

The intent of the curricular tiers in pharmacy leadership and management is to provide exposure to these disciplines in a progressively rigorous manner which is consistent with the level of interest the student has or may develop. The program flexes with their growing interest providing options which are rooted at an introductory level, then progresses to individual elective course selection, area of concentration, graduate degree in pharmacy administration and finally a 2-year management residency. The low student/faculty ratio and tailored curriculum in the comprehensive program offers a special opportunity for students to acquire important skill sets. The pharmacy administration electives utilize a case-based instructional format rather than a traditional didactic instructional format. Each topic is studied using a combination of readings and cases from Harvard Business Review. Participants who complete the entire program will receive training in a selected number of the following areas including:

Outcomes

Historically, feedback from alumni and employers would reflect a desire to increase the leadership and management content in the curriculum. The recent changes have received positive feedback from each of these groups as well as current students. When initially designed, the expectation was student interest would build gradually. As such, a cap was placed on the enrollment in the program. From the time of inception, students have been petitioning the admissions group for waivers to exceed the cap. Initial feedback from those students completing the coursework has been positive and many students who have signed up for one elective as have subsequently enrolled in more. In addition, each year, students have progressed on to the graduate program resulting in expansion efforts. Further, the hospital-based residency in pharmacy administration has now been expanded and a community-based residency in pharmacy administration has been created. Another key element of success has been the level of faculty involvement. Currently, in excess of 20 faculty members have formally participated in the didactic portion of the program and an additional 10 guests have lectured. The level of involvement by adjunct faculty hosting experiential rotations has also significantly increased.

Contact: Scott M. Mark, PharmD, MS, MEd, FASHP, FACHE, FABC, Assistant Professor and Vice Chair, Pharmacy and Therapeutics, University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy, 200 Lothrop Street, 302 Scaife Hall, Pittsburgh, PA 15213. Tel: 412-647-7526. E-mail: smm83@pitt.edu

REFERENCES

- 1.Bootman JL, et al. Approaching the Millennium: The Report of the AACP Janus Commission. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 61:4S–10S. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tsuyaki R.T. and Schindel T.J. Leading Change in Pharmacy Practice: Fully Engaging Pharmacists in Patient-Oriented Healthcare. Centre for Community Pharmacy Research and Interdisciplinary Strategies, December 21, 2004. http://www.epicore.ualberta.ca/compris/LeadingChange.html (Accessed June 19, 2009).

- 3.Leadership: The Nexus Between Challenge and Opportunity. Report of 2002-03 AACP standing committees. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2003;67(3) Article S05. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith WE. “Chair Report for the Professional Affairs Committee”. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2000;64:21S–24S. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sawyer WT. “Chair Report for the Professional Affairs Committee”. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 1996;60:15S–17S. [Google Scholar]

- 6.White SJ. Will There Be a Pharmacy Leadership Crisis? An ASHP Foundation Scholar in Residence Report. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. April 15, 2005;62:845–855. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/62.8.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. “Addressing the Pharmacy Leadership Gap: Leadership as a Professional Obligation” Report from the Student New Practitioner Leadership Task Force submitted to the ASHP Research and Education Foundation Center for Health System Pharmacy Leadership, June 27, 2008.

- 8.White SJ. “Leadership: Successful Alchemy” Harvey AK Whitney Lecture. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. August 2006;63:1497–1503. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kouzes JM, Posner BZ. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. The Student Leadership Challenge: Five Practices for Exemplary Leaders. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Commission to Implement Change in Pharmaceutical Education. Background paper I: What is the mission of pharmaceutical education? Am J Pharm Educ. 1993;57:374–376. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pharmacists for the Future: Report of the Millis Commission. American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, 1975.

- 12. TEAM STEPPS National Implementation Website. http://teamstepps.ahrq.gov/abouttoolsmaterials.htm Accessed October 31, 2008.