Abstract

Over the last 10–15 years, poor African households have had to cope with the burden of increased levels of chronic illness such as HIV/AIDS. How do these households cope with the cost burdens of ill health and healthcare, and has this burden further impoverished them? What policy responses might better support these households? This is a report from the field of the South African Costs and Coping study (SACOCO) – a longitudinal investigation of household experiences in the Agincourt health and demographic surveillance site.

Keywords: Chronic illness, cost burden, health policy, longitudinal household research

Background

The interactions between households and the health system are important determinants of households’ ability to cope with the costs of ill health. Poor quality of healthcare and its cost may deter or delay utilization – particularly by the poor [1]. Health systems are frequently ineffective in reaching the poor, and often impose regressive cost burdens [2]. These problems are aggravated by the increasing burden of chronic illness in poorer countries [3]. Poor households adapt their healthcare use to avoid costs they cannot meet, at the risk of deteriorating health [4]. Financial strategies (e.g. borrowing, and reducing expenditure on other basic needs [5]) used to finance healthcare may jeopardize household livelihoods [6], potentially leading to further impoverishment [7]. Social resources and local infrastructure (such as transport, availability of healthcare) are important in enabling households to cope [8]. Given the relatively small evidence base and the potentially dramatic impacts of health-related costs on household livelihoods, this study was undertaken in order to improve understanding of household experiences, and so provide a basis for developing policies to protect poor households from these cost burdens.

Ethical approval was given by the Committee for Research on Human Subjects (Medical) of the University of Witwatersrand, the Limpopo Province Research Committee, and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Conceptual framework guiding the study

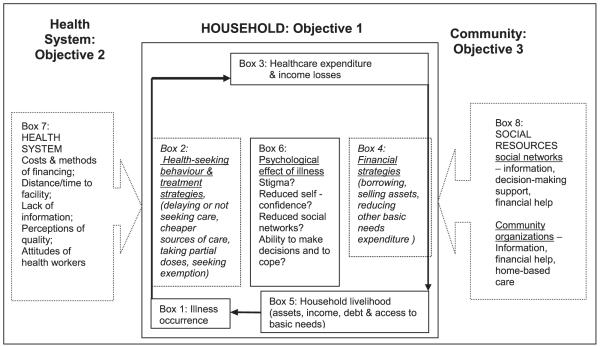

Figure 1 is the conceptual framework guiding the study, first used in Sri Lanka for similar research [9]. It is an adaptation of earlier frameworks used to study household illness costs and coping strategies [10,11], and adds insights from anthropological and livelihood approaches that have analysed the wide variety of resources that people draw on to promote health, seek treatment or cope with illness costs [12-14].

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework: Household costs of illness, and coping strategies.

The central focus is the household that bears the dual burdens of healthcare expenditure and the income losses resulting from taking time off work (Box 3). The level of these costs is influenced by illness occurrence (Box 1) as well as by how households adapt health-seeking behaviour and treatment strategies (Box 2). Households may manage these costs through financial strategies (Box 4). The impacts of these strategies can be assessed by comparing changes in household livelihood over time in response to illness (Box 5). The psychological impact of any negative combination of ill health and increasing poverty can itself reduce ability to make decisions and access to social networks (Box 6). Health system characteristics (including distance to facilities, household perceptions of expected quality of care) influence treatment strategies and illness costs (Box 7). Social resources (including kinship networks, organizations providing home-based care, and various sources of formal and informal credit) assist households in their treatment or cost management strategies (Box 8).

Material and methods

This conceptual framework is inevitably a simplification of a set of complex interactions between household characteristics, events, actions, and effects that are difficult to separate from their context. Because of the need to understand these internal processes in relation to their context a case study approach was chosen, looking at a small number of households in depth. This allows a detailed understanding of interrelated events, effects, and the underlying explanations that are either associated with, or may result in, a particular phenomenon – providing an essential complement to numeric, frequency-based estimates [15].

Several key problems arise when doing case study work at the household level. First, the need to situate the chosen households in the broader national or provincial context. For example, are the chosen exceptionally poor households, or could they arguably represent a large majority of rural poor in South Africa? In this study the choice of the Agincourt health and demographic surveillance site (HDSS) as a study site enabled the SACOCO project to relate the case-study households to the site as a whole, and to other national level data. Second, how should one identify which households to study, particularly given that households needed to have ongoing experience of ill health? In order to look at the role of social networks in mitigating costs of ill health, it was important to ensure case-study households had varying levels of social capital. Similarly, whether there was a local clinic in the community was considered an important variable determining access. All these factors needed to be taken into account in selection, requiring a household survey.

Preliminary information on local healthcare resources, organizations, accepted descriptions of well-being, and health-seeking behaviour patterns were obtained from key informant interviews and focus-group discussions. An initial cross-sectional survey of 280 households (stratified by socioeconomic status) in two villages of the Agincourt HDSS provided a profile of illness and cost burdens, and enabled selection of households for the longitudinal study. The two villages were selected because of their differing levels of infrastructure – one with a clinic and a better transport network, the other without a clinic and more poorly served transport routes.

Thirty case-study households, with high cost burdens of illness, were then selected from the original sample using two criteria: socioeconomic status and level of social resources. In 10 monthly visits, data were collected on health expenditure and descriptive explanations of illness occurrence, treatment actions, use of social networks, and changes to livelihood. Monthly expenditure data were collected three times during the fieldwork.

Eighteen of these households have participated in in-depth interviews on: their life history (description of the household’s long-term experience); illness narratives (of key illnesses, as a background to actions taken during the study period); social networks (a map of key individuals providing support, and the nature of those relationships); health-seeking behaviour and trust (general patterns of health-seeking behaviour, and provider characteristics that influence those patterns), and a final interview to understand how illness and other shocks have shaped the household’s livelihood over the past 10 years or so.

Initially 36 households were selected, but due to the number of tools and length of interview transcripts, loss of fieldworkers, and reluctance from some, visits to six households were stopped. Fieldworkers were responsible for 10 households each, making regular monthly visits, approximately 30 days apart, to collect data on illness events, health expenditure, and coping strategies since the last visit. With the in-depth interviews the information gathered was not limited to the fieldwork period, but often went back several years.

Methodological thoughts from the field

At the time of writing, some 20 months of fieldwork is drawing to a close. At this point, it is worthwhile reflecting on the methodological lessons emerging from such a prolonged fieldwork experience.

Approach and tool development

The study design was intended to allow an iterative process of data collection, with preliminary analyses and reflection shaping subsequent tools – and this is what happened to some extent. However, when the senior researchers are not involved in fieldwork on a daily basis, the intimate engagement with the data does not happen in the field, but only during analysis. Breaking the fieldwork into separate phases with several months’ gap between the household survey and the case-study phase, or within the case-study phase, might have enabled more of an iterative process. For example, if tools are to take account of data already collected, and local cultural perspectives, often embodied in language, this requires time in order to develop understanding and to allow for reflection. The lesson is to build specific and separate phases of fieldwork into the project design, with sufficient time for reflection in between.

Doing qualitative work with fieldworkers

With a structured questionnaire, ensuring consistency across different fieldworkers is not too difficult. With qualitative work, and unstructured interviews, ensuring that fieldworkers have grasped the purpose and intention of the interview, and its relation to the other parts of the study, is key to ensuring useful data are collected. Providing training on the conceptual underpinnings of the study was a first step. Joint tool development and practising interviews through role-playing were important. Once the fieldworkers fully understand the intentions of the study, their own reflections can also provide a useful insight into how to interpret the data. Within this study various steps were taken to enable these insights to be recorded. First, interview notes were written up, by the fieldworkers, on a form containing questions requiring the fieldworkers to both report and reflect on the data they had collected. Second, in-depth interviews were transcribed into the local language, and then translated by the fieldworkers in the same document, facilitating discussion of the meaning or translation of what was said. Finally, regular debriefing with fieldworkers allowed discussion of their interpretation of events in particular households. In some respects the fieldworkers are themselves respondents – both their knowledge of the community, and their understanding and interpretation of events within particular households, need to be recorded. Their interpretation of the data can provide a richer understanding of the meaning of events and decisions, complementing the researchers’ analysis and leading to a greater level of rigour. Researchers need to think through in a concrete way how to engage with fieldworkers to ensure they understand the purpose of the study and all its different components, and to elicit their views and interpretations of the data.

Ethical responsibilities to fieldworkers

The subject of the interviews was often the emotional and difficult topics of severe illness and death. Given the high levels of illness in the area, during the course of fieldwork the fieldworkers themselves experienced illness and death in their own families. Conducting interviews in such a context is not easy. Counselling support was provided to help them deal with their own emotions as well as those of the respondents. Without such support fieldworkers may have found it more difficult to ask questions about emotional issues, leading to certain questions being avoided. Once again the fieldworker is not just a neutral conduit through which data is collected: she/he plays a key role, with valuable insights to contribute, but also requires support to facilitate that role.

Ethical considerations and relationships with households

Some of the households involved in the SACOCO study are desperately poor, in some cases with no means of survival other than friends and relatives, who are often also stretched to their limit. Fieldworkers and researchers have a moral responsibility towards the members of a household they are interviewing who clearly do not have enough food to eat. Visiting households regularly over a year inevitably leads to a social relationship between fieldworkers (who are from neighbouring communities) and respondents – which to some extent binds the fieldworkers (and therefore the project) to the respondents.

Within SACOCO these issues were discussed with the fieldworkers, establishing what type of assistance it was appropriate to provide to households. It was decided to provide food parcels at key religious festivals to all households, periodically to households in desperate need, and at the end of the study. A contribution was made towards funeral expenses when there was a death in a household.

These decisions were guided in part by the fieldworkers’ local knowledge – when to give help – and the judgement as to which households were in desperate need. However, it was important that these discussions took place amongst the group of fieldworkers and researchers, and that fieldworkers were required to justify their views to prevent any personal connections influencing decisions.

It was clear that these gifts at times enabled a household to eke out their food for a whole month, which might have affected the assessment of household livelihoods. Moreover we acknowledge that research, and its accompanying moral responsibility, does lead to change within the study households. However, in this case the in-depth data collection will probably allow us to separate livelihood change from the effect of the gifts.

Difficult as it may be, our experience suggests that the extent of the responsibility of the project to households in a longitudinal study needs to be discussed for each individual case.

Conclusion

Most of the data analysis still lies ahead of us. However, the study is already identifying areas where the health system can do more to help households with high burdens of ill health. Key themes during the analysis are likely to be the following, with policy options being developed over the course of analysis:

The level and impact of ill health cost burdens on households over time.

The patterns of health-seeking behaviour, explanations in terms of demand and supply-side factors, and the impact on the costs of care experienced by the household.

The extent to which transport acts as a key barrier, as well as the costs of care, particularly when patients need to attend a hospital several times in order to initiate the management of common chronic illness such as hypertension, TB, and HIV/AIDS.

The extent to which health-seeking behaviour patterns are determined by social networks that provide access to cash and influence decisions, and by local explanations for ill health (for example the failure to provide a diagnosis and an explanation that has meaning for the patient and family increases the likelihood of non-adherence).

The role that social grants (cash payments) play in enabling households to seek care, and sustain household livelihoods during times of illness when there are few other sources of income. To identify where there are gaps in the formal social security system – either due to inaccessibility of grants, or lack of entitlement to support despite desperate need.

Methodologically, lessons from the study to-date are:

The importance of providing enough time for the iterative process of research – allowing initial data analysis to strengthen subsequent data collection

To place sufficient emphasis on engaging with fieldworkers on the conceptual underpinning of the research, tool development, and interpretation of the data

To acknowledge and provide the emotional and social support necessary to facilitate the fieldworkers’ role

To acknowledge and accept that the moral responsibilities of the research team to particular households may, at times, compromise the research.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Wellcome Trust and the Joint Economic, Aids and Poverty Programme for their financial support, and the MRC/Wits Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research Unit for the demographic data and field base in which to conduct fieldwork. They also wish to thank the field team for their dedication and hard work. Most importantly they wish to thank all the respondents for their time and patience with endless questions.

Footnotes

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed according to the usual Scand J Public Health practice and accepted as a short communication.

References

- [1].Abel-Smith B, Rawall P. Can the poor afford ‘free’ health services? A case study of Tanzania. Health Policy and Planning. 1992;7:329–41. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Castro-Leal F, Dayton J, Demery J, Mehra K. Public social spending in Africa: Do the poor benefit? World Bank Observer. 1999;14(1):49–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Pryer J. When breadwinners fall ill: Preliminary findings from a case study in Bangladesh. IDS Bull. 1989;20:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Goudge J, Govender V. A review of experience concerning household ability to cope with the resource demands of ill-health and health care utilisation. Training and Resource Centre; Harare: 2000. (Regional Network for Equity in Health in Southern Africa (EQUINET) Policy Series No. 3). [Google Scholar]

- [5].Davies S. Are coping strategies a cop out? IDS Bull. 1993;24:60–79. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bebbington A. Capitals and capabilities: A framework for analysing peasant viability, rural livelihoods and poverty. World Development. 1999;27:2021–44. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Corbett J. Poverty and sickness: The high costs of ill health. IDS Bull. 1989;20:58–62. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Moser C. Confronting crisis: A comparative study of household responses to poverty and vulnerability in four poor urban communities. World Bank; Washington, DC: 1996. (Environmentally sustainable development studies and monograph series No. 8). [Google Scholar]

- [9].Russell S. Can households afford to be ill? The role of the health system, material resources and social networks in Sri Lanka. London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, University of London; 2001. PhD thesis. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sauerborn R, Adams A, Hien M. Household strategies to cope with the economic costs of illness. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43:291–301. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Russell S. Ability to pay for health care: Concepts and evidence. Health Policy and Planning. 1996;11:219–37. doi: 10.1093/heapol/11.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Berman P, Kendall C, Bhattacharyya K. The household production of health: Integrating social science perspectives on micro-level health determinants. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38:205–15. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90390-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wallman S, Baker M. Which resources pay for treatment? A model for estimating the informal economy of health. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42:671–9. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00412-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Scoones I. Sustainable rural livelihoods: A framework for analysis. Institute of Development Studies; Brighton: 1998. (IDS Working Paper 72). [Google Scholar]

- [15].Yin RK. Case study research: Design and methods. Sage Publications; London: 1994. [Google Scholar]