Abstract

Background:

In April 1998, the South African government introduced the child-support grant as a poverty-alleviation measure to support the income of poor households and enable them to care for the child.

Aims:

This research aimed to measure equity of access to applications for the child-support grant in an area characterized by poverty. Three questions were addressed: (i) How does socioeconomic status affect the probability of a household applying for a child-care grant? (ii) What household and caregiver characteristics are associated with child-care-grant application? (iii) What barriers to access are experienced by households that do not apply for the child-care grant?

Methods:

The study population of 6,725 households with at least one age-eligible child was drawn from the Agincourt field site, a rural sub-district of South Africa. Data used were obtained from health and demographic surveillance, a child-grant questionnaire, and a household-asset survey. Descriptive cross-tabulations and multivariate logistic regression were used in the analysis.

Results:

Although these grants are intended as a pro-poor intervention, the poorest households are less likely to apply for grants than those in higher socioeconomic bands. Households in lower socioeconomic bands experienced barriers in accessing grants; these related to lack of official documentation, education level of the caregiver and household head, and distance from government service offices.

Conclusions:

Enhancing access will require improved provision of birth certificates and identity documents, efficient coordination and service provision from a range of rural government offices, and creative methods of communication.

Keywords: Agincourt, child support grant, children, demographic surveillance system, equity, inequalities, poverty alleviation, rural, socioeconomic status, South Africa

Background

Various social security benefits, delivered as monetary grants, contribute to a range of measures implemented by the South African government to address poverty and create economic security in the country [1]. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (Act No. 108 of 1996) provides that all citizens have the right to social security, including appropriate social assistance from government, if they are unable to support themselves and their dependants. It obligates the state to take reasonable legislative and other measures, within available resources, to achieve the progressive realization of this right [2]. South Africa is one of very few countries in Africa to have a social security net in place for vulnerable people.

Various social security benefits, delivered as monetary grants, contribute to a range of measures implemented by the South African government to address poverty and create economic security in the country [1]. The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (Act No. 108 of 1996) provides that all citizens have the right to social security, including appropriate social assistance from government, if they are unable to support themselves and their dependants. It obligates the state to take reasonable legislative and other measures, within available resources, to achieve the progressive realization of this right [2]. South Africa is one of very few countries in Africa to have a social security net in place for vulnerable people.

Various grants have been available in South Africa for decades, passing through phases of racially differentiated availability and monetary value [3]. Currently, these grants are the child-support grant, the foster-care grant, the disability grant, the care-dependency grant for children under 18 years with disabilities, the old-age pension, the war-veterans grant, and a grant to tide people over in times of crisis [4]. The Minister of Social Development reported in October 2003 that “two thirds of the income for the poorest quintile is attributable to state transfers and that these grants are received by the poorest 20% of our households who receive the largest portion of the grants”. In spite of this overall success, the minister acknowledged ongoing challenges to increase access to the child-support grant in particular [5]. Research in rural Kwa-Zulu Natal in 2002 [6] showed that only 36% of caregivers of children under seven years had applied for the child-support grant, and the “Means to Live” study, mentioned by Hall & Monson (2006), found that in a poor urban site in the Western Cape and a poor rural site in the Eastern Cape, only two-thirds of eligible children were accessing the grant [7].

These social security benefits play a critical role in the survival of households, especially those most in need, since they target them directly and reverse the bias of earlier, apartheid-era social security programmes [6]. In addition, they have a holistic effect on household welfare and health by bringing income into the household, thereby acting as a preventive rather than a palliative intervention.

This paper focuses on access to the application process for the child-support grant, one of seven social security grants that make up the backbone of the South African social security system [4]. The child-support grant seeks to supplement the income of poor households with children, thereby promoting care of the child and providing for basic needs, and modifying household expenditure patterns [8]. The success of this objective has been confirmed by the South African Community Agency for Social Enquiry (CASE) [9]. In the Mount Frere district in the Eastern Cape Province, for example, the child support grant has clearly helped improve food security and school attendance of poor children [8].

At the time of data collection for this study, late 2002, all children under seven years were eligible for a child support grant of 110 Rand per month (approx. US$35 in 2002 purchasing power parity dallars), subject to the means-tested socioeconomic status of the household. Since then, the age of eligibility has been extended to 14 years and the grant increased to ZAR190 per month in 2006/7. The grant is paid to the caregiver who has primary responsibility for the child and is usually, but not necessarily, the mother of the child. The following documents need to be presented at the time of application: the caregiver's South African identity document, the child's South African birth certificate, and proof of regular household income. If the caregiver is not the parent, proof of legal guardianship and permission to care for the child is required, as well as death certificates of the biological parents or a statement from a social worker declaring that the parents are missing or unable to care for the child [10].

Although the number of children receiving the grant has risen rapidly since its introduction, uptake still remains low as several studies have confirmed [1,3,6,7]. By July 2006, 7.4 million children under the age of 14 were receiving the grant – an estimated 84% of eligible children; however, a little over 1.4 million eligible children were yet to receive the grant [11].

Rationale for the study

Research was conducted to assess differential access to application for the child-support grant and to investigate local barriers to its uptake, with the aim of informing service providers in both government and non-governmental sectors.

Three questions were posed:

How does socioeconomic status affect the probability of a household applying for a child-support grant? In other words, does the grant reach the poorest sector of the population for whom it is intended?

What household and caregiver characteristics are associated with child-support-grant application?

What barriers to access are experienced by eligible households that do not apply for the child-support grant?

Material and methods

Study site

The study was conducted in the Agincourt sub-district of Bushbuckridge District in rural Limpopo Province, northeast South Africa – a district identified as one of the Presidential Nodes of Development owing to its history as a former Bantustan and its continued extreme poverty [12]. The Agincourt site consists of 21 villages comprising 11,500 households and a population of some 70,000 people. Some 30% of the population are former Mozambican refugees who are now self-settled, having moved into the area in the early to late 1980s in the aftermath of the civil war in Mozambique. General amnesties were declared in 1996 and 1999 during which this population could apply for permanent South African residence. While many took advantage of these amnesties, outreach into rural areas was poor and not all former Mozambican refugees were able to apply [13,14].

Relative to other provinces in 2003, Limpopo had achieved poorly in rolling out the government child-support grant. The Department of Social Development 2003 “Project Plan for the Extension of the Child Support Grant” notes that Limpopo Province required “drastic action” in order to reach its targets [15]. At the time of the study there were no government Social Security or Home Affairs offices in the study site, and the cost of a single trip by minibus taxi (usually the only form of transport available) to the nearest public service offices was between ZAR5.00 and ZAR7.50 (approximately US$ 0.50-0.75 in 2002).

Data collection

The study was nested within the Agincourt health and demographic surveillance system (HDSS) that monitors key demographic events and socioeconomic variables in Agincourt sub-district, an area lacking vital registration. Details of the HDSS study design and methods have been published previously [16]. Variables measured annually include: births and other pregnancy outcomes, deaths, in- and out-migrations, household relationships, residence status, nationality of the household head, education, and maternity history [16–19]. The household head, defined as the “main household decision-maker”, is identified by the respondent. A baseline census was conducted in 1992, followed by annual census update rounds. Quality of data is maintained through comprehensive checking at multiple levels, both in the field and in the data room. A high level of population mobility is accounted for in the household membership by including people who are non-resident but retain links with the rural household [13].

During the annual data-collection round, carried out by well-trained and carefully supervised local fieldworkers, additional modules are conducted on all households to support particular analyses and lines of investigation. A household-asset survey and a child-support-grant module, conducted in 2001 and 2002 respectively, provided additional data for this study. The household-asset survey recorded salient features of the living conditions and assets of each household. The questionnaire contained 34 ordinal variables covering areas such as building materials and structure of main dwelling, access to water and electricity, and ownership of appliances, transport, and livestock. An index of household economic status was constructed by combining the variables from the household asset survey and conducting a principal component factor analysis to determine the relevant weights to assign to each variable. The child-support-grant module sought information on the application process in order to assess barriers to grant uptake.

Data from the Agincourt HDSS provided the study population (all households with at least one child under the age of seven years), data on household head (nationality, gender, and education level), data on the caregiver applying for the grant (relationship to child and education level), household-level data (household size and socioeconomic status), and village-level data (distance from nearest public service offices).

Analytic methods

We analysed the village, caregiver, household head, and household variables associated with application for a child-support grant. Cross-tabular descriptive data are presented on frequencies of grant application by variables of interest. Factors are investigated one by one to explore the nature and strength of the relationship between the variables of interest (factors affecting uptake) and the household outcome, namely a grant application. Since many of these factors have influences that potentially confound each other, a multivariate logistic regression looked at a range of household factors while controlling for others. The aim was to estimate a regression equation incorporating the variables that best explained the observed differentials in application for the child support grant.

The denominators for Figures 1 to 3 are age-eligible households that applied for a grant, and for Table I are all households with at least one child under the age of seven years. The total number of households in the sample was 6,725. A household was considered to have submitted an application for a child-support grant if there had been an application irrespective of its outcome (number of households applying=1,886, 28% of eligible households). A household was considered not to have applied if it reported not having applied, or had made only a first exploratory visit to the relevant government offices (number of households not applying although eligible=4,839).

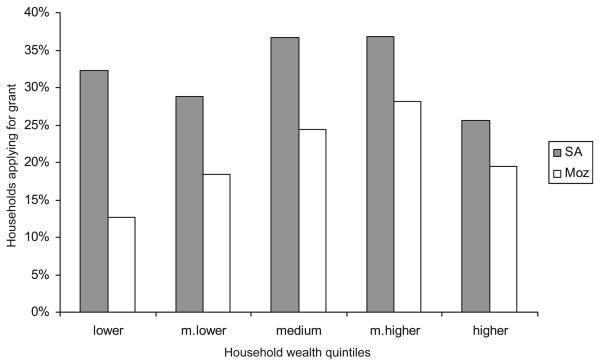

Figure 1.

Child grant applications by wealth quintile of the household and nationality of household head, Agincourt 2002. SA=South African-headed households; Moz=Mozambican-headed households.

Figure 3.

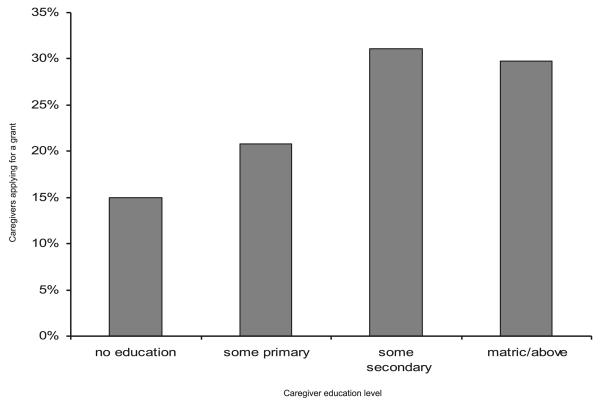

Grant applications by education status of caregiver, Agincourt 2002.

Table I.

Logistic regression results showing the estimated multivariate odds of a household submitting a grant application, by key household- and village-level factors, Agincourt 2002.

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distance expressed as taxi fare | |||

| 5 SAR | ref | ||

| 5.5 SAR | 0.64 | (0.6/0.69) | 0.000 |

| 6 SAR | 0.51 | (0.48/0.54) | 0.000 |

| 6.5 SAR | 0.46 | (0.42/0.5) | 0.000 |

| 7 SAR | 0.38 | (0.35/0.42) | 0.000 |

| 7.5 SAR | 0.43 | (0.39/0.47) | 0.000 |

| Household size (including temporary migrants) | 1.17 | (1.16/1.17) | 0.000 |

| Household head education level | |||

| No education | ref | ||

| Some primary education | 1.16 | (1.1/1.21) | 0.000 |

| Some secondary education | 1.32 | (1.24/1.41) | 0.000 |

| Matric and above | 0.95 | (0.88/1.04) | 0.265 |

| Household socioeconomic status | |||

| Low | ref | ||

| Medium low | 1.03 | (0.95/1.12) | 0.419 |

| Medium | 1.34 | (1.24/1.45) | 0.000 |

| Medium high | 1.50 | (1.39/1.62) | 0.000 |

| High | 1.05 | (0.97/1.14) | 0.262 |

| Household head nationality | |||

| Mozambican | ref | ||

| South African | 1.86 | (1.76/1.95) | 0.000 |

| Household head gender | |||

| Females | ref | ||

| Males | 0.88 | (0.85/0.92) | 0.000 |

Results

Socioeconomic status and nationality

While there is a complex pattern in the relationship between socioeconomic status, nationality and grant application, three findings emerge from the analyses (Figure 1). First, in all wealth quintiles, there is a difference in the degree of grant application by nationality. Former Mozambican refugees (many of whom are now permanent residents or South African citizens) have lower access compared with those South African born, and South African-headed households had a significantly higher likelihood of applying. Second, there is evidence of significantly greater grant application in the medium and medium-high wealth quintiles in both South African and Mozambican households considered separately (Figure 1) and when combined (Table I) compared with the poorer quintiles. Third, the lowest and highest socioeconomic groups in South African and Mozambican households combined appeared less likely to apply for a grant, although there is still considerable grant application within these groups (Table I). This pattern was particularly marked in Mozambican-headed households.

“Distance” to services

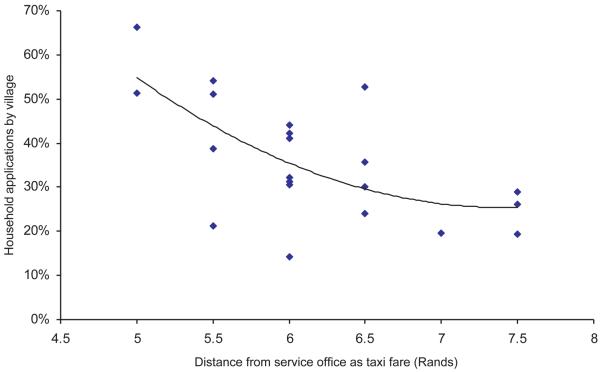

We used cost of a taxi journey from village to public service office (Home Affairs or Social Security) as a proxy for distance. The negative slope on the trend line in Figure 2 suggests an inverse relationship between distance to public service office and application for the grant. The higher the cost of taxi fare, the lower the percentage of households that have completed the grant-application process. Controlling for household-level variables, “distance to service” remains associated with a statistically significant decline in percentage of households completing the application process. In fact, it is statistically significant for each ordinal step in the “distance from service” variable (see Table I).

Figure 2.

Child grant applications as a function of distance to government office, Agincourt 2002.

Relationship of caregiver to child

The vast majority of caregivers applying for a grant are the mother (94.7%). Female relatives, largely grandmothers, were the next most likely to apply (4.9%), with male relatives, such as uncles and fathers, comprising only 0.4%.

Education level of applying caregiver and household head

Figure 3 shows that caregivers with some education were significantly more likely to apply than those with no education: 31% (n=744) and 30% (n=470) of caregivers had “some secondary education” and “matric or above” respectively, compared with 15% (n=202) of caregivers with no education. In addition, odds ratios in Table I indicate that a household head with some primary and secondary education also significantly enhances the likelihood of application.

Nationality and gender of household head

We obtained nationality (South African or Mozambican) and gender of household head from the Agincourt HDSS database. Of the age-eligible South African households (n=4,537), 32% completed a grant application; this contrasts with 20% of age-eligible Mozambican households (n=2,188). This discrepancy may be partly explained by lack of documents proving eligibility among former refugees. Although most had permanent resident status at the time of the study, permanent residents only became eligible for social grants in 2004–05. The uptake of child support grants by households who self-identify as Mozambican in the survey suggests that a small percentage of former refugees had achieved citizenship status by 2002. The HDSS did not record possession of a South African identity document or birth certificate at the time of this study.

Analysis by gender of household head revealed that 27% (n=1,216) of male-headed households and 30% (n=670) of female-headed households had applied for a grant. Although the effect is small, gender of head is a significant predictor, with female heads appearing 12% more likely to submit a grant application than their male counterparts (see Table I).

Household size

Household size shows a positive relationship with the likelihood of grant application, with larger households more likely to apply than smaller ones (odds ratio 1.17; see Table I). Some 25% of households with up to four members applied, compared with 43% of households with over 12 members.

Reasons for not applying for child-support grant

We asked why no application had been made in households that had not applied for a child support grant (n=4,839). More than one response was permitted. Main barriers were lack of official documents (child's birth certificate and caregiver's South African identity document) (71%), not eligible based on income (13%), and poor access to public service offices (8%). Only 2% claimed no knowledge of the grant and 2% did not want the grant. Difficulty in obtaining documents and poor access to service offices partly reflect the same barrier, as access problems inhibit acquisition of documents.

Discussion

The child-support-grant programme was introduced as a national poverty-alleviation strategy in 1998 with the primary objective being to target children most in need. Our data suggest that this is not being achieved within the Agincourt sub-district as the poorest are disadvantaged in accessing grants: only 28% of households with children eligible for the grant were accessing it in 2001. Various aspects of social and human capital are barriers: the poorest and least educated caregivers and families find the process, especially the means test, particularly complicated [20]. Distance from service offices, socioeconomic status, nationality, education level, gender of applying caregiver, and gender of household head emerge as key factors influencing application.

Distance from service office

The further a village is from the service point, the less likely people are to apply for grants. The cost of transport from home to application office is an important barrier, particularly as multiple visits are often required in order to complete the application process. The financial and time costs of obtaining necessary documentation, such as a birth certificate or identity document, also often requiring repeat visits, may be a further factor. This is borne out by results in the “Means to Live” project [6] where 51% and 45% of respondents in the rural and urban sites respectively lacked the necessary documents for application. The Institute for Democracy in South Africa (IDASA), in a 2002 survey on social security capacity, notes the Department of Social Development's concern about physical accessibility of their offices and a lack of transport with which to organize outreach services [21].

While the trend described here is not very strong, given a relatively small band-width in taxi fares, it indicates the need for more work on structural factors affecting access to grants. To increase uptake of grants among the poorest families may require establishing additional offices or providing mobile services in remote areas.

Residence status

Residence status, reflected as nationality of household head, is relevant in two ways: one is the issue of legal status, and the other a cultural element only partially understood. Until 2004, children of former Mozambican refugees were often denied access to the grant, even if they were born in South Africa and their parents had lived there for up to 20 years. Under Article 23 of the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of Children (1999), South Africa as a signatory is required to ensure appropriate protection and humanitarian assistance for refugee children [22]. However, the Mozambicans who fled the civil war in the 1980s were not given refugee status and were thus not covered by the Charter. Through various amnesties in the 1990s, most former Mozambican refugees received permanent resident status, yet remained ineligible for government social welfare grants, including the child-support grant, until 2004 [14]. Despite this, 20% did manage to access grants, presumably by obtaining South African citizenship (through marriage to a South African or naturalization after five years of permanent residence), or by other means including use of a neighbour's documents.

Other effects of “being Mozambican” are suggested in the work of Hargreaves et al. [13]. Several factors affecting child mortality also impact on child-support-grant uptake. Their work shows that households with Mozambican heads are approximately three times more likely than South African households to fall into the poorest quintile of the population. Inequalities in wealth may lead to inequalities in access: Mozambican-headed households are less likely to interact with government officials, more likely to give birth to children at home rather than in clinics or hospitals, and therefore less likely to have the “road-to-health” cards and birth certificates necessary for grant application. The father of the child is more likely to have South African citizenship than the mother and, as mothers are more likely to apply (especially where fathers are absent labour migrants), this would decrease uptake rates in Mozambican headed households.

The contribution of incomplete documentation as a barrier to grant access applies to South African as well as Mozambican-headed households: in all, 71% of households that did not apply for a grant cited this as a reason. In a study in the Eastern Cape Province, 45% of applications were immediately rejected because of missing birth certificates [1].

Socioeconomic status of the household

Socioeconomic status affects access to documentation since multiple visits with repeat travel and time costs are often required. As confirmed by the IDASA study [21], factors limiting access to Home Affairs offices (which issue official documents) are therefore as important as those limiting access to the Department of Social Security (which administers social grants).

Relationship of applying caregiver to child

The fact that 95% of applicants were the mother of the child probably reflects that most children are co-resident with their mothers. However this needs further investigation. A study in KwaZulu-Natal in 2002 showed similar results: 82% of the children for whom the grant was reported were co-resident with their mothers, in contrast to 67% of children without a grant [6]. This may reflect ignorance of the fact that the primary caregiver need not be the biological mother.

Education level of applying caregiver and household head

Household head factors were included in this study in so far as headship reflects the social value system in a household. The cultural orientation and social deprivation of a household head can influence access to services, and social deprivation can affect the entire household. The complex grant-application process, including preliminary acquisition of documents, requires knowledge, time and perseverance, which disadvantages the poorest, least educated and most disempowered households. The relationship of education level of applying caregiver, and that of household head, with likelihood of grant application bears this out. For both caregiver (see Figure 3) and household head there is an inverted u-shaped pattern similar to the effect of socioeconomic status (see Figure 1). The lower grant uptake in the highest education category may be explained by the correlation between higher education and higher socioeconomic status, and therefore lower eligibility by means test and less need to access this source of income. Caregivers with a reasonable level of education are more likely to apply than those with less, partly perhaps through greater knowledge of the grant, from following written materials more easily, and owning a radio or television through which grant information is disseminated. Effective communication is needed: oral explanations in pension queues and schools may be a better way of reaching the poorest than literature and radio campaigns.

Gender of household head

Female-headed households are significantly more likely to apply for grants than male-headed households, and female caregivers are more likely to apply than male relatives. Several factors relating to residence choices and vulnerability affect this. Single-parent households are far more likely to be female-headed, and unmarried mothers and their children are more likely to reside in female-headed households [23]. The data are encouraging in so far as the child-support grant appears to support those women bearing the burden of primary caregiving in a context of poverty.

Size of household

Larger households are more likely to access grants as they may simply house more age-eligible children, and may be more likely to apply a second time having learnt the process with the first application. In addition, larger households with more human capital for childcare and daily tasks such as collecting water, may afford the primary caregiver the time needed to complete the application process.

Limitations of the study

This study examines only that aspect of the child-support-grant process concerned with application. It does not explore other issues associated with access, such as reasons for grant refusal or termination; extent of abuse of the system; and impact of the child-support grant on outcomes such as child nutrition, school attendance, morbidity, mortality, and teenage pregnancy. It explores factors associated with grant application irrespective of whether this is the first or subsequent grant in the household, and does not examine whether subsequent applications are easier once a grant has been obtained. Finally, it was not possible to determine exactly which households were eligible on the basis of documentation status, such as possession of a birth certificate, as these data were not available at the time of the study.

Conclusions

Widespread poverty has long-term negative effects on society, and South Africa is rightly giving alleviation of childhood poverty some priority in its efforts to develop the country and address historic racial and rural/urban inequities. As an important tool, the government has chosen direct financial transfers in the form of grants, investing 14% of its GDP allocated to welfare in 2002 [24]. This level of investment in social security is an unprecedented experiment on the African continent. Giving a cash benefit that follows the child and is paid to a primary caregiver, and not only to a biological caregiver, is also unusual [7]. While this study does not address the impact on childhood poverty, it does highlight some difficulties in implementing so ambitious a programme. Although more recent figures show that the uptake of the child support grant has improved significantly as the programme has expanded, of the 8.8 million South African children eligible for the grant in January 2006, nearly two million had not yet gained access to it [25]. The child-support grant – intended as a holistic intervention for mitigating the myriad impacts of childhood poverty – faces a fundamental difficulty inherent to its implementation, namely the context of poverty, disempowerment and lack of infrastructure. For the grant to reach the most vulnerable households, simultaneous attention to three issues is required: access to government offices in rural areas; efficient coordination of services, particularly provision of official documents; and creative methods of communication targeting community members with low literacy levels. A promising mechanism for addressing these challenges could be a collaboration between government and non-governmental partners promoting access to the application process. Coordinated action between relevant government departments, including the Departments of Social Security and Home Affairs, would go a long way towards promoting access to the child support grant for those most in need.

Acknowledgments

This work has been funded by the Wellcome Trust, UK (Grant no. 058893/Z/99/A), the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, USA, the University of the Witwatersrand and Medical Research Council, South Africa, and the World Bank through the INDEPTH Network. The authors acknowledge with appreciation the Africa Centre, KwaZulu-Natal, on whose data-collection tool our child-support-grant module was based. This research could not have been conducted without the contribution of community leaders, study communities, field team supervisors and field workers. Twine undertook work on this paper during a scientific writing workshop organized and funded by the World Bank through the INDEPTH Network.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed according to the usual Scand J Public Health practice and accepted as an original article.

References

- 1.Giese S, Meintjes H, Croke R, Chamberlain R. Health and social services to address the needs of orphans and other vulnerable children in the context of HIV/AIDS. Research Report and Recommendations. Children's Institute, University of Cape Town; Cape Town: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ardington L, Lund F. Pensions and development: The social security system as a complementary track to programs of reconstruction and development. Centre for Social and Development Studies, University of Natal; Durban: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simkins C. Facing South Africa's social security challenge; Paper presented at the Wits, Brown, Colorado Coloquium; Johannesburg. January 2003; University of the Witwatersrand; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leatt A. Income poverty in South Africa. In: Monson J, Hall K, Smith C, Shung-King M, editors. South African child gauge 2006. Children's Institute, University of Cape Town; Cape Town: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Social Development . Speech by Dr Zola Skweyiya, Minister of Social Development, Ministerial Social Investment Tshifiwa and Update banquet. Sandton Sun and Towers, Johannesburg: Oct 17, 2003. Media Release. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Case A, Hosegood V, Lund F. The reach of the South African child support grant: Evidence from Kwazulu Natal. Development Southern Africa. 2005;22:467–82. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall K, Monson J. Does the means justify the end? Targeting the child support grant. In: Monson J, Hall K, Smith C, Shung-King M, editors. South African child gauge 2006. Children's Institute, University of Cape Town; Cape Town: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sogaula N, van Niekerk R, Noble M, Waddell J, Green C, Sigala M, Samson M, Sanders D, Jackson D. Social security transfers, poverty and chronic illness in the Eastern Cape: An investigation of the relationship between social security grants, the alleviation of rural poverty and chronic illnesses (including those associated with HIV/AIDS). A Case Study of Mount Frere in the Eastern Cape. Centre for the Analysis of South African Social Policy, University of Oxford; Oxford: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kola S, Braehmer S, Kanyane M, Morake R, Mkamanga H. Phasing in the child support grant: A social impact study. CASE; Johannesburg: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National guidelines for social services to children infected and affected by HIV/AIDS . Department of Social Development; South Africa: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Budlender D, Rosa S, Hall K. At all costs? Applying the means test for the child support grant. Children's Institute and the Centre for Actuarial Research, University of Cape Town; Cape Town: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Statistics South Africa Measuring rural development on indicators of poverty in Bushbuckridge (formerly known as Eastern District) 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hargreaves JR, Collinson MA, Kahn K, Clark SJ, Tollman SM. Childhood mortality among former Mozambican refugees and their hosts in rural South Africa. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:1–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolan C. Repatriation from South Africa to Mozambique – undermining durable solutions? In: Koser Black., editor. The end of the refugee cycle? Refugee repatriation and reconstruction. Berghan Books; New York and Oxford: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Department of Social Development, South Africa . Project plan for the extension of the child support grant (CSG) Chief Directorate, Grants Systems and Administration, with support from Process Innovation Management; Pretoria: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collinson MA, Mokoena O, Mgiba N, Kahn K, Tollman SM, Garenne M, Shackleton S, Malomane E. Agincourt Demographic Surveillance System (Agincourt DSS) In: Sankoh O, Kahn K, Mwageni E, et al., editors. Population and health in developing countries. Vol. 1. Population, health and survival at INDEPTH sites; Ottawa: IDRC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collinson MA, Wittenburg MW, Tollman SM, Kahn K. Household dynamics in rural South Africa, 1993–2000. University of the Witwatersrand; Johannesburg: 2000. Working paper of the Agincourt Health and Population Unit. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tollman SM, Herbst K, Garenne M, Gear JJ, Kahn K. The Agincourt demographic and health study: Site description, baseline findings and implications. S Afr Med J. 1999;89:858–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kahn K, Tollman SM, Collinson MA, Clark SJ, Twine R, Clark BD, Shabangu M, Gómez-Olivé FX, Mokoena O, Garenne ML. Research into health, population and social transitions in rural South Africa: Data and methods of the Agincourt Health and Demographic Surveillance System. Scand J Public Health. 2007;35(Suppl 69):8–20. doi: 10.1080/14034950701505031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samson M, Babson O, Haarman C, Haarman D, Khathi G, Mac Quene K, van Niekerk I. Research review on social security reform and the basic income grant for South Africa. International Labour Organisation and Economic Policy Research Unit. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van der Westhuizen C, van Zyl A. Obstacles to the delivery of social security grants. IDASA Budget Brief no. 100. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Organization of African Unity (OAU) African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child. OAU Doc. CAB/LEG/24.9/49 (1990), entered into force. 1999 Nov 29; [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kahn K, Collinson M, Hargreaves J, Clark S, Tollman S. Socio-economic status and child mortality in a rural sub-district of South Africa. In: de Savigny D, Debpuur C, Mwageni E, Nathan R, Razzaque A, Setel P, editors. Measuring health equity in small areas: Findings from demographic surveillance sites. Ashgate; Aldershot: 2005. pp. 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Treasury The budget: A people's guide. 2002 Available online at: http://www.treasury.gov.za/documents/budget/2002/guide/guide.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leatt A. Facts about up-take of the Child Support Grant (January 2006) Children's Institute, University of Cape Town; Cape Town: 2006. [Google Scholar]