Abstract

Aims:

To use a multidisciplinary approach to describe the prevalence, lay beliefs, health impact, and treatment of hypertension in the Agincourt sub-district.

Methods:

A multidisciplinary team used a range of methods including a cross-sectional random sample survey of vascular risk factors in adults aged 35 years and older, and rapid ethnographic assessment. People who had suffered a stroke were identified by a screening questionnaire followed by a detailed history and examination by a clinician to confirm the likely diagnosis of stroke. Workshops were held for nurses working in the local clinics and an audit of blood pressure measuring devices was carried out.

Results:

Some 43% of the population 35 and over had hypertension. There was no relationship with gender but a strong positive relationship with age. Illnesses were classified by the population as being either African, with personal or social causes, or White/Western, with physical causes. The causes of hypertension were stated to be both physical and social. Main sources of treatment were the clinics and hospitals but people also sought help from churches and traditional healers. Some 84% of stroke survivors had evidence of hypertension. Few people received treatment for hypertension, although good levels of control were achieved in some. Barriers to providing effective treatment included unreliable drug supply and unreliable equipment to measure blood pressure.

Conclusions:

Hypertension is a major problem among older people in Agincourt. There is potential for effective secondary prevention. The potential for primary prevention is less clear. Further information on diet is required.

Keywords: Africa, hypertension, vascular disease

Background

The theory of the epidemiologic transition was first developed by Omran [1] and later expanded with an emphasis on vascular disease by Thomas Pearson [2]. Pearson describes four stages of transition, moving from an early stage of “pestilence and famine” to a second stage of “receding pandemics” when the predominant cardiovascular diseases in a population are hypertensive heart disease, and haemorrhagic and lacunar stroke. This represents an over-simplified linear view of the early health transition, not least because it takes no account of the overwhelming impact of HIV/AIDS, but it provides a useful approach to the emergence of cardiovascular disease. Pearson argues that an epidemic of cardiovascular disease can confidently be expected in Africa as countries move beyond the “Age of pestilence and famine” but, more importantly, that such an epidemic can be curtailed.

The theory of the epidemiologic transition was first developed by Omran [1] and later expanded with an emphasis on vascular disease by Thomas Pearson [2]. Pearson describes four stages of transition, moving from an early stage of “pestilence and famine” to a second stage of “receding pandemics” when the predominant cardiovascular diseases in a population are hypertensive heart disease, and haemorrhagic and lacunar stroke. This represents an over-simplified linear view of the early health transition, not least because it takes no account of the overwhelming impact of HIV/AIDS, but it provides a useful approach to the emergence of cardiovascular disease. Pearson argues that an epidemic of cardiovascular disease can confidently be expected in Africa as countries move beyond the “Age of pestilence and famine” but, more importantly, that such an epidemic can be curtailed.

Hypertension and strokes have previously been reported as important health issues for adults in sub-Saharan Africa [3-5], and the high mortality from stroke observed from verbal autopsy investigations in the Agincourt sub-district between 1992 and 1995 [6] led to the development of Southern Africa Stroke Prevention Initiative (SASPI) [7].

This multidisciplinary project aimed to understand and address the increasing burden of stroke and other cardiovascular disease in rural sub-Saharan Africa. The study design was developed using disciplinary knowledge and methodological approaches drawn from neurology, public health, epidemiology, and medical anthropology. The research questions, design, and methods were developed through close collaboration that continued throughout the data collection and analysis. Each component of the study design was influenced and shaped by the multidisciplinary collaboration. We adopted a triangulated approach using a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods. We studied both the general adult population (by a rapid ethnographic assessment and a cross-sectional survey) and the survivors of strokes (by detailed clinical history and examination and indepth interviews) as well as aspects of local healthcare provision through workshops for nurses and an audit of clinical equipment. In this paper we have drawn together the data collected by these different approaches to show how hypertension has emerged as a dominant strand, and how this multi-method approach has provided a deeper and nuanced understanding of the complexities of this clinical and public health problem.

Methods

This research line grew out of the Agincourt health and demographic surveillance programme. The verbal autopsy work was a key factor in initiating the research, the census database was used as a sampling frame for the cross-sectional survey, and the annual census and vital events update in 2002 included two screening questions that enabled us to identify people who may have suffered a stroke (stroke prevalence). Our research methods have been described in detail elsewhere [7-9].

Setting and population

The Agincourt sub-district is in South Africa's rural north-east, adjacent to Mozambique, where the Wits/MRC (Agincourt) Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research Unit monitor deaths, births and migration in a population of around 70,000 people [10] providing a sampling frame for studies such as this. The sub-district has 21 villages. Electricity is available in most villages but not all households, while access to clean water is severely limited. There is high unemployment and, as is common in rural sub-Saharan Africa, considerable labour migration, especially among men [11]. There are five publicly funded primary care clinics and a larger health centre in the sub-district, all staffed by nurses, with occasional visits from doctors based in the local district hospitals. Treatment and drugs are free at these clinics.

Ethics

Informed consent was an important and complicated process. We obtained community consent from the village headman and through community meetings, at which field workers explained what would be involved in the research before starting work in a village. We also took care to inform the local clinic staff when nurses or doctors were working in a village. Individual participants were asked for written individual consent, which in the case of the cross-sectional study involved seeking consent for each component of the interview and clinical examination. Ethics committee approval was granted by both the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (755) and the University of the Witwatersrand (M02-04-63).

Sample for cross-sectional survey

We carried out stratified random sampling. The Agincourt villages were stratified by size (less than 500 households, and 500 households or more) and by whether the village was predominantly a formal settlement (officially recognized) or an informal settlement (settled following an influx of refugees during the Mozambican civil war). Ten villages were randomly selected: four informal, three small formal, and three large formal villages. A 10% random sample of the population (excluding migrant workers) aged over 34 years in the selected villages provided 526 individuals (representing 3% of the 16,705 sub-district population aged over 34). Information on age, gender, and household asset score were available from the Agincourt database. (The household asset score is based on the type and size of dwelling, access to water and electricity, appliances and livestock owned, and transport available).

Cross-sectional survey

We carried out a cross-sectional survey in a random sample of 526 adults aged 35 years and over. One of two local nurses visited participants and administered a questionnaire on health, lifestyle, and use of various resources for healthcare. They measured height, weight, and waist and hip circumference. Blood pressure was measured three times, with five minutes between each measure, using an automated machine (OMRON 705CP) and an appropriate cuff size.

Rapid ethnographic assessment

We gathered qualitative data relating to views on health and illness, and health-seeking behaviour, at the individual and community level using rapid ethnographic assessment [12] in six villages. We undertook 105 interviews with individuals or groups. Participatory techniques [13] such as health walks, village mapping, illness ranking, and card sorting were undertaken with a number of different groups.

Identifying prevalent stroke cases

People who might have experienced a stroke were identified through the annual census update. Census field workers were trained in asking about adult members of the household who had experienced a sudden onset of one-sided weakness or a recognized stroke. A study clinician accompanied by an interpreter visited all those identified, took a history and carried out a clinical examination to determine whether or not the person had experienced a stroke and assessed the presence of risk factors for stroke. Blood pressure was measured as described above using an OMRON 705CP or M5-I blood pressure monitor. Semi-structured interviews were undertaken with a sub-sample of 35 individuals and their main carers from the 103 individuals that were identified as having had a stroke.

Understanding the role of local clinics

Two workshops were held for nurses working in local clinics at which nurses were invited to share their knowledge on the treatment of stroke and hypertension, and to identify problems with the provision of care for people with hypertension. Later, with the help of a medical student, we carried out an audit of blood pressure measuring devices in local clinics. In each of the five clinics and health centre we assessed the number and type of blood pressure measuring devices available as well as the range of cuffs. We then assessed the accuracy and working condition of the blood pressure measuring devices according to methods previously used by recognized authorities in the field [14].

Definition of hypertension

We report the mean of the second two blood pressure measurements. We used the JNCV definition of stage 1 and stage 2 hypertension [15]. Thus, a person was considered stage 1 hypertensive if the systolic blood pressure was greater than 139 mmHg, or the diastolic greater than 89 mmHg; and stage 2 hypertensive if the systolic blood pressure was greater than 159 mmHg, or the diastolic greater than 95 mmHg. People on anti-hypertensive therapy were described as hypertensive even if their blood pressure readings were below the cut-off for stage 1 hypertension.

Results

A total of 402 (24% men) participated; a response rate of 77%. At the mid-year 2003 census update there were around 12,500 people aged over 34 years and resident in the field site of whom 32% were men, reflecting the dominance of male labour migration (Collinson M, personal communication).

Prevalence of hypertension in adults 35 years and over

Of the 402 participants, 359 (68%) provided blood pressure measurements. Hypertension was the commonest risk factor in this community, and 43% of the population had some degree of hypertension (Table I). There was no difference between men and women in the prevalence of hypertension (Table I) or mean level of blood pressure (Table II), but there was a strongly positive relationship with age (Table III). Among men, but not women, there was some suggestion that blood pressure might correlate positively with body mass index and waist quartile.

Table I.

Percentage (counts) of respondents 35 years and older with or without hypertension, by sex, Agincourt, 2002/3.

| Male | Female | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure | |||

| Normala not on pharmacological treatment | 55.8 (48) | 57.8 (158) | 57.4 (206) |

| Normal on pharmacological treatment | 4.7 (4) | 5.5 (15) | 5.3 (19) |

| Mild hypertensionb, not on pharmacological treatment | 16.3 (14) | 13.9 (38) | 14.5 (52) |

| Mild hypertension on pharmacological treatment | 1.2 (1) | 2.2 (6) | 2.0 (7) |

| Moderate hypertensionc, not on pharmacological treatment | 18.6 (16) | 17.6 (48) | 17.8 (64) |

| Moderate hypertension on pharmacological treatment | 3.5 (3) | 2.9 (8) | 3.1 (11) |

Systolic<140 and diastolic<90 mmHg.

Systolic ≥140, <160 and/or diastolic ≥90, <95 mmHg.

Systolic ≥160 and/or diastolic ≥95 mmHg.

Table II.

Mean (95% confidence interval) of blood pressure by sex, 35 years and older, Agincourt, 2002/3.

| Clinical measurement | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) n=86M 273F | 136 (131, 142) | 132 (129, 136) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) n=86M 273F | 81 (78, 84) | 80 (78, 82) |

Table III.

Odds ratios of a diagnosis of hypertension by age group, body mass index group, and sex-specific waist quartiles adjusted for age, Agincourt, 2002/3.

| Male |

Female |

|

|---|---|---|

| Crude odds ratio (95% CI) | Crude odds ratio (95% CI) | |

| Age group | ||

| n=86 (M), 273 (F) | ||

| 35 to 54 years | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 55 to 74 years | 1.85 (0.70, 4.85) | 2.89 (1.67, 5.00) |

| 75 or more years | 2.08 (0.65, 6.67) | 5.12 (2.10, 12.4) |

| Body mass index group | Age-adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) | Age-adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) |

| N=76 (M), 257 (F) | ||

| Less than 20 kg/m2 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 20<25 kg/m2 | 2.55 (0.84, 7.75) | 0.70 (0.28, 1.76) |

| 25<30 kg/m2 | 4.81 (1.21,19.0) | 0.87 (0.35, 2.13) |

| 30<35 kg/m2 | – | 1.18 (0.44, 3.20) |

| 35<40 kg/m2 | – | 1.00 (0.26, 3.81) |

| 40 kg/m2or more | – | 4.47 (0.37, 54.0) |

| Waist quartile | ||

| n=79 (M), 260 (F) | ||

| I | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| II | 1.65 (0.40, 6.86) | 1.21 (0.58, 2.53) |

| III | 3.29 (0.77, 14.1) | 1.50 (0.72, 3.15) |

| IV | 5.67 (1.34, 24.0) | 0.93 (0.43, 2.02) |

Hypertension defined as a mean systolic reading ≥140 mmHg, or a mean diastolic reading ≥90 mmHg or on antihypertensive therapy. Age in years entered as a continuous variable when adjusting for age.

Local understanding of hypertension based on rapid ethnographic assessment and household interviews

Illnesses were categorized as xintu (African) with personal or social causes, or xilungu (white, Western) with naturalistic causes. “High blood” or mavabyi ya high blood (the illness of high blood) was the way in which hypertension was referred to. It was regarded as one of the common conditions that affect adults. It was also considered to be linked to a “xintu” illness ndhatwsa, of which high blood is one component along with a burning sensation in the legs and possibly black dots on the palms of the hands and feet. People repeatedly stated that the causes of hypertension were both physical and social. One of the commonly cited physical causes was the modern diet which contains more salt, sugar and oil than in the past. Additionally, people were concerned that “high blood” may be hereditary. The social causes were linked to stress and “thinking too much” about the difficulties in their lives (see Box 1).

Box 1. Question: WHAT ARE THE CAUSES OF HIGH BLOOD?

Prophet

“Looking at it, I think high blood is caused by lack of peace of mind, by being always worried by any problem you might encounter, like poverty. The problems we face outside cause problems like high blood inside our bodies. Problems can cause not only high blood for you but they can also cause heart disease.”

037M Section 5 para 32 Interview with a Prophet

Gardening group

Speaker 8; M: We want to live more of a Western lifestyle than African, but we are not doing it the right way. We put four teaspoons of sugar in a cup of tea/coffee. Whites add one. We also spread jam both sides of the piece of bread so that it is very sweet. We also put a lot of cooking oil and salt in our foods.

Speaker 5; F: Having problems and thinking a lot about them can also cause high blood.

Excerpt from a group interview with a gardening group 0518 paragraphs 82–92

Youth group

Speaker 2: There might be a lot of causes that are unknown but I believe thinking too much does contribute because if you have problems and you are always worried your blood pressure goes up.

Speaker 4: It is caused by being overweight, therefore it is important for people to exercise and to avoid oily foods and foods with too much salt.

Speaker 1: I also have observed that people with high blood are those who always complain about family/personal problems so I think thinking too much causes high blood.

Speaker 3: I think eating too much sugar causes it. Excerpt from a youth group 0519 paragraphs 40–62

People were clear that this is a condition treated in the main by tablets obtained from health staff at clinics, hospitals or private doctors (see Box 2). Some people drank herbal teas obtained from the churches and traditional health practitioners (healers and prophets), and described how they prepared a herbal mixture by boiling certain kinds of roots for drinking in small quantities. People also mentioned prayer as being good for one's well-being, and treatment given by a prophet or healer would be accompanied by prayer.

Box 2.

“High blood is one of the illnesses experienced in this community. Most of the people in the village are suffering from this illness. It is caused by too much sugar in the body, too much cooking oil in foodstuff, and lack of exercises. High blood will never rise up for a person who indulges/involves himself or herself in physical activities. A person can also catch high blood easily if he/she can think too much about his or her problems. People usually go to the clinic or hospital for the treatment of this illness. I have never seen a person consulting at a traditional healer for the treatment of this illness. Tablets are used for the treatment of this illness. A person who suffers from high blood experiences difficulty when breathing, and he/she gets tired easily.”

0525F young woman

“We have a problem of high blood in our village and we call it ‘ndhatswha’ [literally meaning burning]. People with this illness always feel tired and have difficulty in walking for a long distance. They have difficulty in breathing. Whenever one experience this symptoms they consult the clinic and the nurse will tell them they have high blood illness. They go to the clinic for treatment and they collect tablets continuously but I have no idea what kind of tablets. Other people go to the traditional healers for treatment and there they are told they have (ndhatswha) but I have no idea what kind of treatment do they get from the traditional healers. The sequence usually followed by many community members when unwell is that they firstly go to the clinic and if still not well then they go to the hospital and then if still not well they consult traditional healers.”

0520 young man

Hypertension in stroke survivors

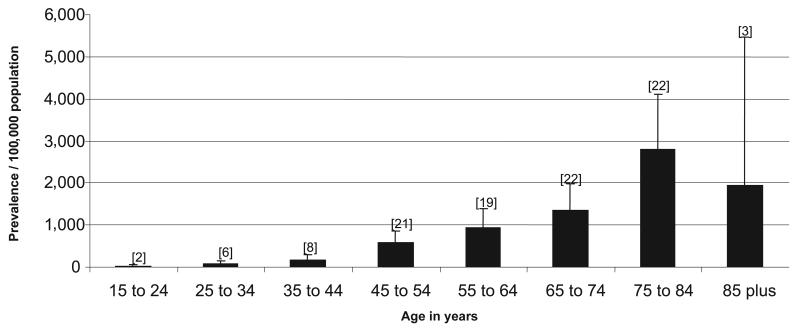

We identified a total of 103 cases of stroke, giving a crude prevalence of 300/100,000 aged over 15 years after adjustment for non-contact (i.e. the individuals who screened positive but we did not examine). There was a steep age gradient (Figure 1). Two blood pressure readings were available for 97 of the 103 persons examined. Seventy-three participants (71%) had hypertension at the time of the visit, and a further 14 participants had evidence of end-organ damage from previous hypertension, or reported having been on anti-hypertensive therapy. In total, therefore, 84% of people who survived a stroke had some evidence of hypertension, and hypertension was quite clearly the dominant cardiovascular risk factor (Table IV). Only 30 of the 103 stroke survivors (29%) reported to the examining clinician that anti-hypertensive medication was prescribed following their stroke. At the time of examination, only eight people were taking anti-hypertensive treatment and only one of these had a blood pressure within the normal range (116/74 mmHg). Although our study was conducted prior to publication of the PROGRESS study, when use of post-stroke anti-hypertensive treatment became routine worldwide, very few hypertensive or previously treated patients in Agincourt were receiving treatment when we assessed them [16,17]. Only one person was using aspirin.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of stroke by age group adjusted for proportion not examined, Agincourt, 2002. Whiskers represent the upper 95% confidence interval and the number above the whisker is the number of stroke survivors in the age group.

Table IV.

Characteristics of stroke survivors, Agincourt, 2002.

| Percentage (number ) of stroke survivors |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factor | Men (n=37) | Women (n=66) | Total (n=103) |

| On history | |||

| Diabetic | 5.4 (2) | 15.2 (10) | 11.7 (12) |

| Symptoms of angina | 13.5 (5) | 9.1 (6) | 10.7 (11) |

| Current smokers | 21.6 (8) | 1.5 (1) | 8.7 (9) |

| Never smokers | 45.9 (17) | 93.9 (62) | 76.7 (79) |

| Currently drinks alcohol | 29.7 (11) | 15.2 (10) | 20.4 (21) |

| On examination | |||

| Hypertensive | 64.9 (24) | 74.2 (49) | 70.9 (73) |

| Any evidence of hypertension | 83.8 (31) | 84.8 (56) | 84.5 (87) |

| Carotid bruits | 2.7 (1) | 4.5 (3) | 3.9 (4) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 5.4 (2) | 4.5 (3) | 4.9 (5) |

Seeking care for hypertension

In the cross-sectional survey, the nurses asked respondents about places or people they had visited in the previous month “about their health”, naming all the possible sources in turn to jog their memory, and asking also about the purpose of the visit. This provided a “snapshot” of health-seeking behaviour in the area. The 402 respondents reported a total of 266 visits within the month and 25 of the visits related to hypertension. Table V shows that the majority of the visits relating to hypertension were with an allopathic practitioner, which again suggests that hypertension is primarily understood as a physical disease responding to biomedical care.

Table V.

Sources of healthcare visited in last month, Agincourt, 2002/3.

| Source of care | Number of visits reported |

Number (percentage of all visits) related to hypertension |

|---|---|---|

| Local clinic | 121 | 18 (14.9%) |

| Private doctor | 22 | 1 (4.5%) |

| Hospital (inpatient or outpatient) |

14 | 4 (28.6%) |

| Traditional healer | 47 | 1 (2.1%) |

| Faith healer | 41 | 0 |

| Shop | 21 | 1 (4.8%) |

| Total | 266 | 25 (9.4%) |

Providing care for people with hypertension

While the number of people receiving treatment for hypertension was low, it appears that, in those using pharmacological treatment, good levels of control were being achieved. Of the 153 people identified as hypertensive in the cross-sectional survey, 37 (24.2%) had used pharmacological treatment for blood pressure in the last week and 19 of the 37 (51.4%) had a mean blood pressure reading below 140/90 mm Hg. This was not true for the eight (of 103) stroke survivors using anti-hypertensive medication, where only one person had blood pressure that was adequately controlled.

Clinic nurses who attended the workshops identified several barriers to more effective care of people with hypertension. There was a problem with the availability of drugs in the clinics. The supply of drugs to clinics was variable with monthly supplies arriving late or in insufficient quantity due to a variety of logistic problems. Clinics sometimes ran out of one or more of the drugs needed to treat hypertension. As a result, they either had to deny treatment to patients or switch the treatment to another drug, both actions that are likely to reduce adherence to medication. Nurses also said that they were often unable to monitor blood pressure levels in those with hypertension due to lack of equipment in the clinics. They complained about the poor condition of the sphygmomanometers, with many not functioning at all. Nurses also complained about the small size of the cuffs available, which were inappropriate for blood pressure measurement on larger people.

We carried out an audit of blood pressure measuring devices and found that all but one of the devices were in working order when used with a cuff provided by the research team. However, none was in satisfactory condition when used with the cuffs available in the clinics. In addition, only one of the cuffs met the size recommendations of the South African Hypertension Guidelines [18].

Discussion

The use of a multidisciplinary collaborative approach drawing on the theoretical, empirical and methodological approaches of neurology, epidemiology, public health and medical anthropology has generated findings that not only describe the prevalence and present management of hypertension, but also explain lay understandings of the condition and associated health-seeking behaviour. Neither qualitative nor quantitative methods alone would have adequately delineated this issue at both the individual and community level, and interfacing these methods and approaches has generated a multidimensional, nuanced understanding of the problem.

The data clearly demonstrate that hypertension is a major health problem in older people, that it is well recognized within the community and, very probably, a major causal factor in the high death rate from strokes that had previously been identified through verbal autopsy data. We found higher prevalence rates of hypertension (44% men, 42% women) than those reported in the South African Demographic and Health Survey for non-urban black Africans (19% men, 21% women) [19]. Our data are comparable with the South African survey in that the SASPI nurses were trained by a member of staff from that survey, but the age range of our survey was older. Earlier rural studies elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa have reported prevalence rates of less than 15% [20–22] but more recent rural studies in Tanzania and Ghana have found higher rates [23,24]. These high recorded levels of hypertension, with concomitant increase in the burden of stroke as found in rural South Africa, fit with Pearson's theory of the vascular health transition [2]. Findings suggest that the population of Agincourt, along with the rest of rural sub-Saharan Africa, is likely to see a rapid increase in incidence of stroke and other hypertension-related diseases.

Murray and colleagues [25] have recently argued that, in countries such as South Africa, interventions to address cardiovascular risk will be highly cost-effective at both the personal level, through using drugs to reduce risk, and at the social level by addressing the salt content of food and providing health education. Our findings support this argument, to the extent of showing the already considerable proportion of people with elevated blood pressure, and demonstrating that the health system is capable of delivering effective antihypertensive therapy to at least some in the population. In those people receiving drug treatment for hypertension, more than half achieve good control. In South Africa, treatment at community clinics and the drugs prescribed there are free. Nevertheless, the majority of people with high blood pressure (75.8%) were not taking any treatment. Factors that militate against effective treatment include difficulties with transport to clinics, difficulties with drug supplies, and problems with equipment within clinics [9] but there are many other interrelated factors.

Our data confirm the widespread nature of this problem in a rural Southern African population. Addressing the problem will require a locally appropriate package of interventions at both the individual and the community level. The precise nature of these interventions will need to be developed through negotiated partnerships between the healthcare providers (largely in the public sector), national policy-makers and local communities.

The potential role of health education or other more sophisticated health promotion interventions is not yet clear. Any effective community intervention to address hypertension will need to take into consideration, and build upon, lay understandings of high blood pressure and the related patterns of health-seeking behaviour that include both traditional and allopathic health practitioners. Diet is a possible area for intervention. We know very little about the salt content of the usual diet in the area although anecdotal evidence suggests that it is high in salt. Health promotion interventions that aim to identify the major sources of salt and address them appropriately may well be both effective and cost-effective. Such interventions would probably include a combination of negotiation with food manufacturers and health education at population level.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the Wellcome Trust (ref 0647/Z/01/Z). The authors are grateful to the many participants from the Agincourt area who gave their time. Dr Krisela Steyn and Mrs Jean Fourie from the Chronic Disease of Lifestyle Research Unit, Medical Research Council, Cape Town provided training and ongoing quality control for the study nurses. Professor Franco Cappuccio provided helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed according to the usual Scand J Public Health practice and accepted as an original article.

References

- 1.Omran AR. The epidemiologic transition: A theory of the epidemiology of population change. Milbank Memorial Fund Q. 1971;29:509–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pearson TA. Cardiovascular disease in developing countries: Myths, realities, and opportunities. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 1999;13:95–104. doi: 10.1023/a:1007727924276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reed D. The paradox of high risk of stroke in populations with low risk of coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;131:579–88. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker RW, McLarty DG, Kitange HM, Whiting D, Masuki G, Mtasiwa DM, et al. Stroke mortality in urban and rural Tanzania. Lancet. 2000;355:1684–87. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker R. Hypertension and stroke in sub-Saharan Africa. Transactions of the R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88:609–11. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(94)90193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kahn K, Tollman SM. Stroke in rural South Africa – contributing to the little known about a big problem. S Afr Med J. 1999;89:63–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.SASPI Team Prevalence of stroke survivors in rural South Africa: Results from the Southern Africa Stroke Prevention Initiative (SASPI) Agincourt field site. Stroke. 2004;35:627–32. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000117096.61838.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.SASPI Team Secondary prevention of stroke – results from the Southern Africa Stroke Prevention Initiative (SASPI) study, Agincourt Field Site. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:503–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.SASPI Team The social diagnostics of stroke like symptoms: Healers, doctors and prophets in Agincourt, Limpopo Province, South Africa. J Biosoc Sci. 2004;36:433–43. doi: 10.1017/s0021932004006662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tollman SM, Herbst K, Garenne M. The Agincourt demographic and health study, Phase I. Department of Community Health, University of the Witwatersrand; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahn K, Tollman S, Thorogood M, Connor M, Garenne M, Collinson M, Hundt G. Older Adults and the Health Transition in Agincourt, rural South Africa: New Understanding, Growing Complexity. In: Cohen B, Menken J, editors. Aging in sub-Saharan Africa: Recommendations for furthering research. Washington DC: National Academy of Sciences Press: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pelto G, Gove S. Developing a focused ethnographic study for the WHO acute respiratory infection (ARI) programme. In: Scrimshaw NS, Gleason GR, editors. Rapid assessment procedures: Qualitative methodologies for planning and evaluation of health related programmes. International Nutrition Foundation for Developing Countries; Boston, MA: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chambers R. Rural development: Putting the last first. Longman; Harlow, UK: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burke MJTH, O'Malley K, Fitzgerald DJ, O'Brien ET. Sphygmomanometers in hospital and family practice: Problems and recommendations. B Med J. 1982;285:469–71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6340.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute . The Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure. US Department of Health and Social Services; Washington, DC: 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.PROGRESS Collaborative Group Randomised trial of a perindopril-based blood-pressure-lowering regimen among 6105 individuals with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2001;358:1033–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacMahon S, Neal B, Rodgers A, Chalmers J. The PROGRESS trial three years later: Time for more action, less distraction. Br Med J. 2004;329:1073. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7472.970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milne FJ, Pinkey-Atkinson VJ. Hypertension guidelines 2003 update. S Afr Med J. 2004;94:209–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medical Research Council South African Demographic and Health Survey 1998. Demographic and Health Surveys. Macro International. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooper R, Rotimi C, Ataman S, McGee D, Osotimehin B, Kadiri S, et al. The prevalence of hypertension in seven populations of West African origin. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:160–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.2.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giles WH, Pacque M, Greene BM, Taylor HR, Munoz B, Cutler M, et al. Prevalence of hypertension in rural West Africa. Am J Med Sci. 1994;308:271–5. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199411000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mbanya J-C, Minkoulou EM, Salah JN, Balkau B. The prevalence of hypertension in rural and urban Cameroon. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:181–5. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cappuccio FP, Micah FB, Emmett L, Kerry SM, Antwi S, Martin-Peprah R, et al. Prevalence, detection, management, and control of hypertension in Ashanti, West Africa. Hypertension. 2004;43:1017–22. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000126176.03319.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edwards RUN, Mugasi F, Whiting D, Rashid S, Kissima J, Aspray TJ, Alberti KGMM. Hypertension prevalence and care in an urban and rural area of Tanzania. J Hypertens. 2000;18:145–52. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murray CJL, Lauer JA, Hutubessy RCW, Niessen L, Tomijima N, Anthony R, et al. Effectiveness and costs of interventions to lower systolic blood pressure and cholesterol: A global and regional analysis on reduction of cardiovascular-disease risk. Lancet. 2003;361:717–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]