Abstract

Much social science research on HIV/AIDS focuses on its impact within affected communities and how people try to cope with its consequences. Based on fieldwork in rural South Africa, this article shows ways in which the inhabitants of a village react to illness, in general, and the role their reactions play in facilitating the spread of communicable diseases such as HIV/AIDS. There is potentially a strong connection between the manner in which people respond to illness in general, and actual transmission of infection. By influencing the way villagers react to episodes of ill health, folk beliefs about illness and illness causation may create avenues for more people to become infected. This suggests that efforts to combat the HIV/AIDS pandemic cannot succeed without tackling the effects of folk beliefs. Therefore, in addressing the problem of HIV/AIDS, experts should focus on more than disseminating information about cause and transmission, and promoting abstinence, safe sex, and other technocratic fixes. Our findings suggest that people need information to facilitate not only decision-making about how to self-protect against infection, but also appropriate responses when infection has already occurred.

Keywords: Allopathic, diagnosis, HIV/AIDS, infection, information, medicine, South Africa, therapy, traditional, witchcraft

Background

More than anywhere else, communities across Africa have been devastated by the HIV/AIDS pandemic. South Africa has been particularly hit, with the pandemic compounded by the system of labour migration that takes people from rural areas to urban centres or other areas in search of employment. Though its full impact remains unknown, it is acknowledged that the back-and-forth movement of migrant workers is a critical factor in the spread of HIV/AIDS [1]. As in many areas of the developing world, especially remote rural settings, information regarding HIV/AIDS is widespread but generally limited to the mechanics of infection and transmission, and ways in which it could be avoided [2-4]. It does not extend to interpretation of symptoms that might suggest infection, and how to respond in such instances. Consequently, as in the case of other illnesses, afflictions related to HIV/AIDS are interpreted within a prevailing framework of folk beliefs regarding illness and its causes. Similarly, responses are confined to what is locally believed to be appropriate therapy.

Folk beliefs, as factors in facilitating transmission of disease, and as important targets for anti-HIV/AIDS programmes, do not feature in policy discussions. This paper explores their centrality to the problems posed by the HIV/AIDS pandemic. It does so by examining two phenomena: how residents in Tiko1 village respond to ill health, and key influences on their health-seeking behaviour.

It shows that, as elsewhere [5,6], in Tiko reaction to illness is generally pragmatic. Folk beliefs are important in decision-making concerning choice of therapy, with people adopting multiple strategies believed to constitute an appropriate response. Broadly, reaction consists of self-treatment and engagement of the services of allopathic and/or traditional practitioners. The nature of response to a particular affliction depends on its presumed severity or threat to well-being, as well as beliefs regarding cause and effective intervention [7]. The paper calls for HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment programmes to widen their focus beyond the current emphasis on technical issues [2-4].

Aim

The paper aims to demonstrate the implications of health-seeking behaviour for the spread of infectious diseases. Focusing on HIV/AIDS, it shows that the way in which people in Tiko village react to ill health creates avenues for the disease to spread widely through the community. Strategies for combating AIDS that prioritize information dissemination and biomedical treatment – such as the rollout of anti-retroviral therapy – are vitally important; nevertheless they leave significant gaps that continue to facilitate infection. A major gap is the reading, interpretation, and response by communities to signs of possible infection.

In Tiko, for example, few people possess information on illness and illness-causation of the kind that would enable them to look beyond folk beliefs and explanations when faced with affliction. The paper calls for an emphasis on creating awareness of alternative ways of reading and interpreting symptoms and responding to ill health. It highlights the need for this by focusing on afflictions that the medical fraternity has established as having strong links to HIV and AIDS infection. As we shall see, villagers do not link such conditions to HIV/AIDS, about which they have general information especially on cause and modes of transmission, but to ancestors, bewitchment, and violation of taboos. This reading and interpretation assigns their treatment to non-allopathic therapies that neither address the underlying pathogenesis, nor therefore, reduce the risk of further spread.

Material and methods

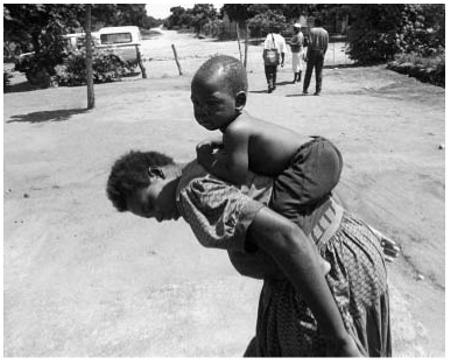

The paper draws on 18 months of ethnographic research on livelihoods and well-being in Tiko (2002–03). As a village, Tiko was established in 1965 under the apartheid-era policy of ‘villagization’, which saw the repatriation of black people in urban centres to rural areas, and the herding of sparsely settled rural populations into planned and crowded settlements [8]. It is located in the north-eastern lowveld of South Africa – close to the border with Mozambique – and has a population of 2,850 people comprising a mix of locally born South Africans and Mozambican immigrants, of which there are 926.2 The immigrants left Mozambique as war refugees during the late 1980s, or earlier as labour migrants. The village is deprived and somewhat isolated, with weak communication links, and is therefore well suited to studies examining the effects and outcomes associated with pro-poor public health policy.

This component of the research effort was designed around a core group of informants who at the time of fieldwork were in poor health; and those who, during earlier phases of work, had been ill or caring for ill members of their households, some of whom had since died. Many informants had been identified through day-to-day interactions, sometimes through people asking what we were doing, and social visits by members of the research team during the extended period of residence in the village. Through snowball sampling, informal exchanges, and participant and non-participant observation at events such as festive gatherings, funerals, and pension day, people with visible signs of ill health were noted and other informants were identified. In addition, a public meeting was convened to ask for volunteers willing to share their illness experiences or those of their kin. Messages were conveyed to individuals not in attendance, but with experiences to share, to also volunteer for interviews. A total of 27 people from the same number of households volunteered; 55 in-depth interviews were conducted, supplemented by wide-ranging informal discussions and conversations, some repeated over several weeks, with other villagers of all ages.

The majority of respondents, however, were older adults, mostly women, the latter because of the labour migration system that takes large numbers of adult men from the village for long periods of time to work or to seek employment opportunities. Nonetheless, whenever migrants returned to the village on leave or on short visits, many were interviewed formally or informally about their illness experiences, understanding of illness causation, interpretation of symptoms, and health-seeking behaviour. While the preponderance of older adults may appear to bias the research, it is justified by younger people’s limited experience of complicated illness, and still-evolving ideas about illness causation and therapy options. As the research progressed it became clear that older people, often in consultation with neighbours, relatives, and friends, chose therapy for young members of their households and, if not, exercised a great deal of influence over the choices they made.

Results

As in other sociocultural contexts [5,6,9,10], the villagers of Tiko cluster afflictions into four distinct categories distinguished according to cause and the therapy believed to constitute suitable treatment. Broadly they attribute ill health to natural causes, these being everyday hazards that only God can explain: eating large quantities of certain foods (sugar, salt, cooking oil, corn meal) or eating them too often; and human agency consisting of witchcraft, poisoning or ‘feeding’ (xidyiso3). Xidyiso is a form of witchcraft that entails someone being ‘fed’ (literally or in a dream) with something injurious to their health. There are also two types of pollution, ritual and environmental, believed to cause ill health. Ritual pollution arises from violation of conventions governing traditional rituals, while environmental pollution could come in the form of dust for example, which is said to cause tuberculosis (TB) in miners and ex-miners.

Folk beliefs concerning illness and illness causation influence the decision whether to select traditional or allopathic therapy. As elsewhere [11-14], the supposed relative efficacy of available alternatives determines the specific treatment chosen as well as any other treatments used thereafter or in tandem. Therapy is therefore chosen on the basis of beliefs about both disease causation and the suitability of particular treatment options. Other influences on health-seeking behaviour include personal experience, rumours, and material circumstances. Members of social and kin networks, acting as therapy referees,4 are important sources of advice on causes of illness and suitable treatment.

For the purposes of this discussion we are interested in specific afflictions: those attributed to ritual or environmental pollution, such as tuberculosis (TB) or tindzaka,5 and those attributed to bewitchment such as the dreaded xifulana or xifula.6 Xifulana comes in the form of stroke-like symptoms, severe headache or stomach-ache and diarrhoea, and various forms of bodily swellings and skin lesions. Although by no means a sure sign of HIV/AIDS, these afflictions or their symptoms commonly manifest themselves in people at advanced stages of the illness.

According to folk wisdom in Tiko, suitable treatment for these conditions is to be found in traditional therapy, with the allopathic option posing considerable risk to the well-being of sufferers. For example, it is believed that xifulana, like jogu among the Dagomba [15] and lubanzi among the Bakongo [5], if treated by allopathic therapy using a hypodermic injection, leads to certain death:

If you go to hospital, you will die; you will die. They should tell you that it is caused by witchcraft and send you home for the right treatment. If they don’t and instead give you an injection, you’re dead.

While TB is considered treatable by both traditional and allopathic therapy, usually traditional therapy is sought before a visit is paid to a clinic or hospital [7].

When it first started we took him to a traditional healer, there at Justicia. But traditional medicine did not help. So we brought him back home and took him to the hospital where they gave him pills. It is the pills which helped.

Those unwilling or unable to seek the services of traditional therapists resort to prophets (maporofeti), these being clerics of charismatic churches. Their therapy combines religious rituals, allopathic medicines, and other substances [14,16]. In the absence of improvement, they may decide to seek traditional therapy:

You go to a traditional healer when things are bad. But you have to give our father [God] a chance first. If the devil defeats him, you go to a traditional healer.

Only when traditional therapists and prophets are judged to have failed to provide effective treatment, when the situation has become desperate, is help sought from hospitals, in many cases as a last resort, by which time it may be too late for the treatment to be effective. This is not to suggest, though, that choice of therapy is always a straightforward matter, or even that therapies are used in linear fashion. As in other contexts [5,17-20], in Tiko, shopping for therapy is pragmatic and pluralistic with people sometimes using different therapies simultaneously. What is incontrovertible, however, is the heavy reliance on traditional therapy to treat afflictions that can only be managed effectively by biomedical therapy, and whose prevention can best be achieved through behavioural change arising from understanding based on valid information about illness, causation, and suitability of different types of therapy.

Discussion and conclusions

The use of traditional therapies to treat communicable diseases that have their genesis in human-to-human transmission renders communities like Tiko vulnerable to devastation by afflictions such as HIV/AIDS, the spread of which depends to a large extent on people not knowing whether they are infected, and continuing to behave in ways that facilitate person-to-person transmission. In communities where people first attribute certain serious infections to non-pathogenic causes, and then seek to treat them using therapy that is ineffective, laying emphasis – as health professionals and policy-makers tend to do – on infrastructure, supplies, and personnel provides only part of the solution.

A central problem in Tiko seems to be the prevailing folk reading and interpretation of symptoms, in ignorance or disregard of alternative explanations. A villager who suffers from TB, whether HIV/AIDS-related or not, and interprets it as tindzaka, is likely to infect many others in the community. Given the dominance of this interpretation, those infected are in turn likely to infect yet new victims. In the case of sexually transmitted HIV/AIDS, those carrying the virus and showing symptoms of illness, while attributing it to witchcraft, are not likely to take measures to avoid infecting others. These explanations of cause, acting in concert with other risk factors, probably contribute to the high levels of HIV/AIDS and TB in South Africa [21].

While resident in Tiko during fieldwork, we established that people working in urban areas, and widely rumoured to be infected with HIV/AIDS, acquired new sexual partners while visiting the village. Some of them went on to succumb to HIV/AIDS-related afflictions during the course of the fieldwork, which gave us the opportunity, through day-to-day information-exchange, rumour and gossip among villagers, to establish the extent of the sexual liaisons they had had over the years with different people in the village. The revelations pointed to overlapping sexual networks, suggesting that a large number of people were at risk of infection. One particular example, the story of a young couple, illuminates the situation:7 When the wife started ailing, rumours that she had AIDS, contracted from a young migrant labourer who had committed suicide upon learning that he was infected, began circulating. Despite advice and pressure from relatives and in-laws that she go for an HIV test, the young woman refused, maintaining that she had been bewitched.

Meanwhile she continued to lose weight and show other signs of chronic illness. She tried various therapies, including over-the-counter allopathic medicines and concoctions from maporofeti. In due course, when her condition worsened, she was taken to a traditional healer where she was admitted. Just before she died she was returned to her parents’ home in the village. Not long after her death, her husband took another young woman from the same village for a wife. Months later, he became gravely ill and was taken to a traditional healer where he was admitted. In the meantime, amidst rumours that he too was dying of AIDS, his mother reacted by accusing relatives (among them her own daughter) of bewitching her son. Shortly afterwards, the young man also died. It is possible that the new wife, left widowed, had by now contracted the disease. Given that in both cases witchcraft was singled out as the cause of illness, other members of the same sexual network remained – conceivably unknowingly – at high risk of infection.

In such a social environment, combating illness and limiting its spread through intensified access to well-contextualized and credible information (preferably provided by members of the local community), seems as urgent as the common public sector approach emphasizing personal precautions, provision of health infrastructure and recruitment of additional personnel.

Over the course of the fieldwork, deaths were relatively frequent in Tiko and neighbouring communities, with multiple funerals held almost every week. Many of the deaths were attributed either to witchcraft or to AIDS (ma-egis), a disease that many of our respondents, possibly because of generational factors, confessed to knowing little about both in terms of ‘where it comes from’ ( ha hi switivi swaku mavabyi lawa ma ta hi kwini), and ‘what to do about it’ (hi ta maka njani?). They were, however, firm in the belief that witchcraft was the major cause of illness and death. The dominance of witchcraft as an explanatory factor in illness causation is demonstrated by the case of a 17-year-old woman with vaginal warts. At her own initiative she had visited a clinic, where she had been diagnosed as suffering from a sexually transmitted disease, and been referred to the local hospital. She then told her aunt, with whom she lived, about it. After consultation with kin and friends, her aunt was convinced that she had been bewitched and took her to a traditional healer. Weeks later, the traditional healer’s medicine had had no effect, but no other action had been taken.

Throughout the village there was a feeling that something had gone wrong in the community, a sentiment often expressed by reference to ‘the increase in witchcraft’, for even the little-understood AIDS, we were told, could be caused by bewitchment. This sort of reaction, attributing a new, little understood, and deadly phenomenon to the occult, is consistent with the way witchcraft as an explanatory concept has been applied in this and other contexts to explain mysterious and frightening occurrences [14,22].

The villagers’ sentiments concerning the mysterious nature of HIV/AIDS and response to HIV/AIDS-related afflictions capture the main argument of this paper – that there is a direct connection between firmly held folk beliefs, health-seeking behaviour, and health outcomes. It is therefore imperative that efforts to combat HIV/AIDS and related afflictions be double-pronged. Not only should they prioritize ‘supply-side’ strategies such as provision and upgrading of infrastructure, hiring of personnel, and delivery of medicines and supplies, but they should also emphasize the communication of alternative, well-contextualized and targeted information regarding illness, illness causation, and different therapy options. Armed with a broader spectrum of information than is available from folk wisdom alone, people should be in a better position to make more informed decisions about how to avoid illness and, if afflicted, how to respond appropriately.

With specific reference to HIV/AIDS in a context such as Tiko, efforts should be made to provide easily accessible, culturally resonant information concerning its nature and causes, the mechanics of its transmission and how it can be avoided and, if infected, how one should respond. In countries showing demonstrable progress, these approaches have been championed at the highest levels of political leadership and embraced by a wide crosssection of national and sub-national bodies [4]. For professionals at the front line of combating communicable diseases such as HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis, this research shows, as other anthropologists have so often done [17,23,24], that understanding local explanations of illness and health-seeking behaviour is fundamental to an effective public health response.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, USA, for providing funding for the research; David Turton of the Refugee Studies Centre, Oxford, UK, for his overall contribution to the success of the project; Christina Qhibi for her able research assistance; and the villagers of Tiko for their hospitality and time.

Footnotes

Tiko is a fictitious name for the study village.

Agincourt health and demographic surveillance system, University of the Witwatersrand. Annual census, 2003.

Pronounced ‘shiji-iso’.

The idea of ‘therapy referees’ is inspired by Janzen & Arkinstall’s [5] ‘therapy managers’ or ‘therapy management groups’.

An affliction with TB-like symptoms that may or may not be labelled as ‘TB’.

Pronounced ‘shifulana’ and ‘shifula’ respectively.

This (abridged) account is pieced together from numerous conversations with a wide range of informants and, in one case, email correspondence over a number of months from 2001 to 2005.

This paper has been independently peer-reviewed according to the usual Scand J Public Health practice and accepted as an original article.

References

- [1].Lurie MN, Williams B, Zuma K, Mkaya-Mwamburi D, Garnett G, Sturm AW, et al. The impact of migration on HIV-1 transmission in South Africa: A study of migrant and non-migrant men and their partners. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;40:149–156. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200302000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kaler A. AIDS-talk in everyday life: the presence of HIV/AIDS in men’s informal conversation in southern Malawi. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:285–97. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Neema S, Musisi N, Kibombo R. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in Uganda: A synthesis of research evidence. The Alan Guttmacher Institute; Dec, 2004. (Occasional Report No. 14). [Google Scholar]

- [4].Barnett T, Whiteside A. AIDS in the twenty-first century: disease and globalization. Palgrave MacMillan; Basingstoke: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Janzen JM, Arkinstall MD. The quest for therapy in Lower Zaire. University of California Press; Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Steen TW, Mazonde GN. Ngaka ya Setswana, Ngaka ya Sekgoa or both? Health seeking behaviour in Botswana with pulmonary tuberculosis. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:163–72. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00329-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Golooba-Mutebi F, Tollman SM. Shopping for health: Affliction and response in a South African village. 2005. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- [8].De Wet C. Moving together, drifting apart: Betterment planning and villagisation in a South African homeland. University of Witwatersrand Press; Johannesburg: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cumes DM. Africa in my bones: A surgeon’s odyssey into the spirit world of African healing. New Africa Books; Claremont: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ngubane H. Body and mind in Zulu medicine: An ethnography of health and disease in Nyuswa-Zulu thought and practice. Academic Press; London: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Getachew NK. Among the pastoral Afar in Ethiopia. Tradition, continuity and socio-economic change. International Books in association with OSSREA; Utrecht: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Levine RA. Witchcraft and sorcery in a Gusii community. In: Middleton J, Winter EH, editors. Witchcraft and sorcery in East Africa. Routledge & Kegan Paul; London: 1963. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ashforth A. Madumo: A man bewitched. David Phillip Publishers; Cape Town: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Niehaus I. Witchcraft, power and politics: Exploring the occult in the South African lowveld. Pluto Press; David Philip; London: Capetown: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bierlich B. Injections and the fear of death: An essay on the limits of biomedicine among the Dagomba of Northern Ghana. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:703–13. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hundt GL, Stuttaford M, Ngoma B. The social diagnostics of stroke-like symptoms: Healers, doctors and prophets in Agincourt, Limpopo Province, South Africa. J Biosoc Sci. 2004;36:433–43. doi: 10.1017/s0021932004006662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Spector RE. Cultural diversity in health and illness. Appleton-Century-Crofts; Norwalk, CT: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Inhorn MC. Quest for conception: Gender, infertility, and Egyptian medical traditions. University of Pennsylvania Press; Philadelphia: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gregg JL. Virtually virgins: Sexual strategies and cervical cancer in Recife, Brazil. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Finkler K. Women in pain: Gender and morbidity in Mexico. University of Pennsylvania Press; Philadelphia: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pronyk PM, Makhubele MB, Hargreaves JR, Tollman SM, Hausler HP. Assessing health seeking behaviour among tuberculosis patients in rural South Africa. Int J Tuberculosis Lung Disease. 2001;5:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Golooba-Mutebi F. Witchcraft, social cohesion and participation in a South African village. Development and Change. 2005;36:937–58. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Scheper-Hughes N. Death without weeping: The violence of everyday life in Brazil. University of California Press; Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Napolitano V. Migration, mujercitas, and medicine men: Living in urban Mexico. University of California Press; Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: 2002. [Google Scholar]