Abstract

PYK2, a major cell adhesion-activated tyrosine kinase, is highly expressed in macrophages and implicated in macrophage activation and inflammatory response. However, mechanisms by which PYK2 regulates inflammatory response are beginning to be understood. In this study, we demonstrate that PYK2 interacts with MyD88, a crucial signaling adaptor protein in LPS and PGN-induced NF-κB activation, in vitro and in macrophages. This interaction, increased in macrophages, stimulated by LPS, requires the death domain of MyD88. PYK2-deficient macrophages exhibit reduced phosphorylation and degradation of IκB, an inhibitor of NF-κB nuclear translocation, and decreased NF-κB activation and IL-1β expression by LPS. These results suggest that via interaction with MyD88, PYK2 is involved in modulating cytokine (e.g., LPS) stimulation of NF-κB activity and signaling, providing a mechanism underlying PYK2 regulation of an inflammatory response.

Keywords: LPS, TLR, integrin, molecule

Introduction

Endotoxin or LPS, a molecule produced by Gram-negative bacteria, and PGN, produced from Staphylococcus aureus, are well-studied agonists for TLR family receptors, which activate innate immune cells such as macrophages and adaptive immune B cells, primarily via TLR4 signaling. TLR family members induce an inflammatory signaling response via cytoplasmic TIRAPs, including MyD88, TIRAP, TIR domain-containing adaptor-inducing IFN-β, and TIR domain-containing adaptor-inducing IFN-β-related adaptor molecule [1,2,3]. Most TLRs, with the exception of TLR3, use a MyD88-dependent pathway, which in turn, recruits the IRAK complex, including four subunits: two active kinases (IRAK-1 and IRAK-4) and two noncatalytic subunits (IRAK-2 and IRAK-M) [3]. Subsequently, IRAK-1 is phosphorylated by IRAK-4, and phosphorylated IRAK-1 associates with TRAF6, activating the NF-κB and MAPKs [3,4,5]. In the case of NF-κB activation, via the IKK complex, the IRAK-TRAF6 complex leads to phosphorylation and degradation of IκB, enabling the nuclear translocation of NF-κB. The activation of NF-κB and MAPK induces the transcription of various inflammatory genes, including IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α [3, 6, 7], leading to proinflammatory or innate immune response.

PYK2, a FAK-related tyrosine kinase, is highly expressed in hematopoietic cells including macrophages. It plays an important role in regulating B cell migration and osteoclastic bone resorption [8, 9] and is implicated in neuronal synaptic plasticity [10, 11]. In addition, several lines of evidence have implicated PYK2 in an inflammatory response. It is highly expressed in monocytes/macrophages [12]. It can be activated in response to cytokine stimulation [13], in addition to cell adhesion. It is involved in cell adhesion, spreading, and migration of monocytes/macrophages and neutrophils [14]. Thus, it is believed that PYK2 may regulate an inflammatory response by recruitment of monocytes/neutrophil to the sites of inflammation. However, it remains unclear exactly how PYK2 regulates an inflammatory response.

In this study, we provide evidence for PYK2 in regulating LPS and PGN-induced NF-κB activation. Our results indicate that PYK2 knockdown macrophages exhibit reduced LPS/PGN-induced phosphorylation of IκB, decreased p65 NF-κB nuclear translocation, and impaired NF-κB-derived IL-1β expression. In addition, we demonstrate that PYK2 interacts with MyD88, and such an interaction may underlie PYK2 regulation of LPS-induced NF-κB activation and signaling. Our findings provide a new mechanism underlying PYK2 modulation of LPS/PGN signaling and inflammatory response.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

LPS (from Escherichia coli 055:B5) and PGN (from S. aureus) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). mAb were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA; anti-Myc), Sigma-Aldrich (anti-Flag), Transduction Labs (Lexington, KY, USA; anti-PYK2 and 4G10), Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA; anti-phospho-IκB), and Sigma-Aldrich (β-actin). Polyclonal antibodies were purchased from Biosource International, Inc. (Camarillo, CA, USA; anti-PY402), Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA; MyD88), Cell Signaling Technology (anti-IκB), and Santa Cruz Biotechnology (anti-p65).

Expression vectors

The cDNAs of FAK and PYK2 were subcloned into mammalian expression vectors downstream of a Myc epitope tag (MEQKLISEEDL), as described previously [15]. The cDNAs of MyD88 were RT-PCR-amplified and subcloned into mammalian expression vectors downstream of a Flag tag. The miRNA expression vectors that suppress expression of PYK2 were generated by the BLOCK-iT™ Lentiviral miR RNA Expression System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), as described previously [16]. Briefly, based on mouse PYK2 sequence analysis by a program provided by Invitrogen, three regions for each gene were picked and cloned into the pcDNA™6.2-GW/EmGFP-miR expression vector to yield pcDNA™6.2-GW/EmGFP-miRNA-PYK2. They were cotransfected with the PYK2 expression construct into HEK-293 cells to identify effective clones based on their ability to suppress PYK2 expression by Western blot analysis. Their efficiency in suppressing specific gene expression was confirmed further by immunostaining analysis. The sequences for the miRNA-PYK2 construct are as follows: PYK2-1761-T: 5′-TGCTGTAAGGATACAGTTCCATGACGGTTTTGGCCACTGACTGACCGTCATGGCTGTATCCTTA-3′ and PYK2-1761-B: 5′-CCTGTAAGGATACAGCCATGACGGTCAGTCAGTGGCCAAAACCGTCATGGAACTGTATCCTTAC-3′.

PYK2 shRNA constructs were generated by using the BLOCK-IT U6 RNAi Entry Vector kit (Invitrogen). The sequences of shRNA primers were as follows. Pyk2-1738-T: 5′-CAC CGG ACC CAG AAA CTG CTC AAC ACG AAT GTT GAG CAG TTT CTG GGT CC-3′ and Pyk2-1738-B: 5′-AAA AGG ACC CAG AAA CTG CTC AAC ATT CGT GTT GAG CAG TTT CTG GGT CC-3′. The numbers in the names of shRNA constructs indicate the targeting nucleotide sequences.

Cell culture, transfection, and NF-κB reporter assay

RAW264.7 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in DMEM, supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and gentamicin (100 mg/ml; Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2 as previously described [17].

For the NF-κB reporter assay, a NF-κB-dependent luciferase reporter plasmid (0.5 μg; a kind gift from Dr. Cong-yi Wang, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, GA, USA) and a pCMV-β-galactosidase plasmid (1.0 μg; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA) were transfected with indicated plasmids into RAW264.7 cells using Lipofectamine 2000. Luciferase activity is represented as relative luciferase units of firefly per β-galactosidase activity. Each reporter gene assay was performed in triple.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed in modified RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl at pH 7.4, 150 mM sodium chloride, 1% NP-40, 0.25% sodium-deoxycholate, and proteinase inhibitors). Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western blot analyses with indicated antibodies.

Protein–protein interaction assays

For coimmunoprecipitation assays, HEK-293 or RAW264.7 cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 units ml–1 penicillin G, and streptomycin (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Cells were plated at a density of 1 ×106 cells/10 cm culture dish and allowed to grow for 12 h before transfection using Lipofectmine 2000. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were lysed in modified RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.4, 150 mM sodium chloride, 1% NP-40, 0.25% sodium-deoxycholate, and proteinase inhibitors). Immunoprecipitation was carried out as described previously [18]. Cell lysates (500 μg protein) were incubated with the indicated antibodies (1–2 μg) at 4°C for 1 h in a final volume of 1 ml modified RIPA buffer with constant rocking. After the addition of protein A–G agarose beads, the reactions were incubated at 4°C for 1 h. Immune complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting.

GST pull-down assay was carried out as described previously [18]. Transiently transfected HEK-293 cells were lysed in the modified RIPA buffer. Cell lysates were precleared with GST immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose 4B (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and then incubated with the indicated GST fusion proteins (2–5 μg), immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads at 4°C for 1 h with constant rocking. The beads were washed three times with modified RIPA buffer, and bound proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblotting.

Immunostaining and confocal image analysis

Briefly, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde or –20°C methanol for 20 min, permeated, blocked with 5% bovine serum, and incubated with antibodies against high-mobility group box 1 (rabbit polyclonal, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and PYK2 (mouse monoclonal). Double-labeled immunostaining was performed with appropriate fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies. Images were taken on a Zeiss fluorescence microscope at 40× and/or 63×.

Real-time PCR analysis

The mRNA expression levels of IL-1β were evaluated by real-time PCR. Real-time quantification was based on the LightCycler assay using SYBR Green I reaction mixture for PCR with the LightCycler Instrument (Roche, Manheim, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Statistically significant differences between groups versus control were obtained with a Student’s t-test, and significant differences are indicated by asterisks.

RESULTS

PYK2 interaction with MyD88 in vitro

To investigate functions of PYK2, we searched for binding proteins for PYK2 with the hypothesis that these proteins may mediate or regulate PYK2 signaling. MyD88, an adaptor protein essential for the TLR family receptor-induced NF-κB activation, was identified. Using an in vitro pull-down assay, we mapped the MyD88 interaction domain in the PYK2 C terminus (Fig. 1A). As GST-PYK2/FAK full-length fusion proteins were unstable and failed to be produced (data not shown), various GST-PYK2/FAK C terminus fusion proteins, immobilized on agarose beads, were incubated with lysates of cells expressing Flag-MyD88. GST alone did not precipitate with MyD88 nor did PYK2Δ1–869 or PYK2Δ1–902 (Fig. 1A). In contrast, GST-fusion protein containing PYK2 C terminus (e.g., PYK2Δ1–781) pulled down MyD88 (Fig. 1A). Note that GST-FAK-Cterm also pulled down MyD88 weakly (Fig. 1A). These results suggest that PYK2 associates with the MyD88 via its C-terminal domain. To determine whether PYK2/FAK interacts with MyD88 in mammalian cells, we examined their association in HEK-293 cells coexpressing Flag-tagged MyD88 and Myc-tagged PYK2/FAK. As shown in Figure 1B, PYK2 was detected in immunoprecipitates of MyD88, suggesting an interaction of PYK2 with MyD88 in mammalian cells. Note that PYK2 kinase activity appeared to regulate this interaction. A reduced binding to MyD88 by PYK2-KD, a kinase mutant, was observed, as compared with PYK2-WT (wild-type) (Fig. 1B), implicating a regulation of the interaction by PYK2 catalytic activity (Fig. 1C). In addition, MyD88 appeared to interact with PYK2 much stronger than that to FAK in mammalian expression cells (Fig. 1B). MyD88 appeared to be weakly tyrosine-phosphorylated upon coexpression of PYK2, but not FAK (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

PYK2 interaction with MyD88. (A) PYK2 interaction with MyD88 in vitro via PYK2 C-terminal domain. Cos-7 cells expressing Flag-tagged MyD88 were lysed, and resulting lysates were incubated with indicated GST fusion proteins (∼5 μg) immobilized on beads. Bound proteins were probed with anti-Flag antibodies (upper right). GST fusion proteins were revealed by Coomassie staining (lower right). The data were summarized (left). ++, Strong binding; +, weak binding; –, no binding. FAT, Focal adhesion targeting domain; IB, immunoblot. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation (IP) of MyD88 with PYK2 that is regulated by PYK2 catalytic activity. (C) A working model to illustrate enhanced PYK2-MyD88 interaction by PYK2 catalytic activity. FERM, Protein 4.1, ezrin, radixin, moesin. (D) Weak tyrosine phosphorylation of MyD88 in cells coexpressing PYK2 but not FAK. (B and D) HEK-293 cells were transiently transfected with indicated plasmids. Cell lysates were incubated with anti-Flag antibodies to immunoprecipitate MyD88 complexes, which were resolved on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies against Myc or RC20 [a phosphotyrosine antibody (Ptyr)]. Flag-tagged MyD88 and Myc-tagged FAK/PYK2 in lysates were revealed by immunoblotting with anti-Flag and anti-Myc antibodies, respectively.

MyD88 protein is an adaptor protein containing multiple domains, including a DD, ID, and TIR domain [19] (Fig. 2A). We then mapped the region in MyD88 necessary for the interaction by coimmunoprecipitation assay. MyD88 containing the DD (MyD88-Fl, MyD88ΔTIR, and MyD88ΔID) interacted with PYK2, whereas deletion of the DD (MyD88ΔDD) reduced the interaction significantly (Fig. 2B), suggesting that DD in MyD88 is essential for its interaction with PYK2.

Figure 2.

Mapping PYK2 interaction domain in MyD88. (A) Illustration of MyD88 deletion mutants and its interaction with PYK2. ++, Strong interaction/inhibition of PY402; –, no detectable interaction/no decrease of PY402. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation of PYK2 with MyD88 deletion mutants. HEK-293 cells were transiently transfected with indicated plasmids. Cell lysates were incubated with anti-Flag antibodies to immunoprecipitate MyD88 complexes, which were resolved on SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies against Myc. Flag-tagged MyD88 and Myc-tagged PYK2 in lysates were revealed by immunoblotting with anti-Flag and anti-Myc antibodies, respectively. In addition, PY402 was also examined. Note that deletion of the DD abolished the interaction. Interestingly, PY402 was decreased in cells coexpressing MyD88, but not the MyD88ΔDD mutant. These results were summarized in A.

We also examined PY402 in lysates coexpressing with or without MyD88 or its deletion mutants. Of interest to note is that PY402 was decreased upon coexpressing MyD88-Fl, MyD88ΔTIR, or MyD88ΔID, but not MyD88ΔDD mutant (Fig. 2, A and B), a reciprocal relationship to their interaction with PYK2. These results suggest that MyD88 may negatively regulate PYK2 autophosphorylation/catalytic activity in a manner dependent on their interaction.

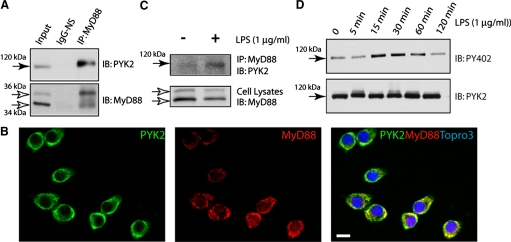

PYK2-MyD88 interaction in macrophages and up-regulated by LPS

PYK2 and MyD88 are expressed in macrophages. To determine if endogenous PYK2 interacts with MyD88 in macrophages, RAW264.7 cells stimulated with or without LPS were subjected for coimmunoprecipitation assay. Indeed, endogenous PYK2 associated with the immunocomplexes of MyD88 in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 3A). Upon LPS stimulation (for 10 min), PYK2-MyD88 association was increased slightly (Fig. 3B). We then determined where, subcellularly, they interact in RAW264.7 cells. Coimmunostaining analysis indicated that PYK2 and MyD88 appeared to be colocalized at cytoplasm (Fig. 3C). Note that LPS also stimulated PYK2 tyrosine phosphorylation (at Y402) in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 3D), which may underlie LPS-induced PYK2-MyD88 association. Taken together, these results demonstrate an interaction of MyD88 with PYK2 in a macrophage cell line, which is regulated by LPS stimulation in a time-dependent manner.

Figure 3.

PYK2 interaction with MyD88 in macrophages. (A and B) Coimmunoprecipitation of MyD88 with PYK2 in RAW264.7 cell lysates stimulated with or without LPS (1 μg/ml, 10 min). Lysates (5 μg) were loaded as input. IgG-NS, IgG-nonspecific. Original bar, 20 μm. (C) Coimmunostaining analysis of PYK2 and MyD88 in RAW264.7 cells, which were fixed and immunostained with anti-PYK2 and anti-MyD88 antibodies. (D) Western blot analysis of LPS-induced PYK2 tyrosine phosphorylation indicated antibodies.

PYK2 regulation of MyD88-mediated NF-κB activation by LPS and PGN

MyD88 is an essential protein in LPS-induced NF-κB activation [3, 4]. We thus asked if PYK2 is involved in this event. LPS activates NF-κB via the induction of phosphorylation of IκB and its degradation [3, 4]. To assess if this event requires PYK2, we first examined LPS-induced IκB phosphorylation and degradation in RAW264.7 macrophage cell lines stably expressing control or shRNA of PYK2. Two cell lines (#1 and #3) showed suppressed PYK2 expression by its shRNA, but not PYK2-related protein, FAK, or PYK2-associated proteins, paxillin and p130cas (Fig. 4A). Control and shRNA-PYK2 (#1) cell lines were then treated with LPS for different times, and the cell lysates were subjected for Western blotting analysis using antibodies against phospho-IκB. As shown in Figure 4B, LPS induced IκB phosphorylation and degradation in a time-dependent manner in control cells. However, this event was delayed significantly in shRNA-PYK2-expressing cells with a significant increase of IκB phosphorylation at 60 min after stimulation (Fig. 4, B and C). Consistently, no significant decrease of the IκB protein level/degradation was observed in shRNA-PYK2-expressing cells (Fig. 4B). We then asked if PYK2 is required for PGN-induced IκB phosphorylation. PGN is another agonist that activates MyD88-dependent signaling and induced phosphorylation of IκB and Erk/MAPKs [4, 20, 21]. Indeed, the phosphorylation of IκB in PYK2-deficient cells in response to PGN was abolished (Fig. 4, D and E). In contrast, the control shRNA-expressing cells responded to PGN with a significant induction of IκB phosphorylation (Fig. 4, D and E). Taken together, these results suggest that PYK2 is required for LPS- and PGN-induced IκB phosphorylation.

Figure 4.

Requirement of PYK2 for LPS- and PGN-induced phosphorylation and degradation of IκB. (A) Western blot analysis of RAW264.7 macrophages stably expressing control shRNA and PYK2 shRNA using indicated antibodies. Note that PYK2 is selectively reduced in shRNA-PYK2 but not in control shRNA-expressing cells. FAK, paxillin, and p130cas were not affected in PYK2-shRNA-expressing cells. (B) Impaired time course of LPS-induced phosphorylation (p) and degradation of IκB in PYK2-deficient RAW264.7 cells, which when expressing control and shRNA-PYK2, were stimulated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for the indicated time. Cell lysates were subjected for Western blot analysis using indicated antibodies. Levels of total β-actin were used as controls for protein loading. (C) Quantification analysis of data from B. The values displayed are combined from at least three separate experiments and are expressed as fold increase over the basal values without stimulation. *, #, P < 0.01, significant decrease/increase from the control (t-test). (D) Reduced PGN induced phosphorylation of IκB in PYK2-deficient RAW264.7 cells, which when expressing control and PYK2 shRNA, were stimulated with or without PGN (10 ng/ml) for different times. Lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis using indicated antibodies. (E) Quantification analysis of data from D. The values displayed are combined from at least two separate experiments and are expressed as fold increase over the basal values without stimulation. *, P < 0.01, significant difference from the control (t-test).

As IκB is an inhibitor of NF-κB nuclear translocation, we thus examined whether PYK2 regulates NF-κB translocation, an event associated with IκB degradation and NF-κB activation. p65, a major subunit of the NF-κB protein complex, translocates into the nuclei when IκB is degraded. To compare LPS-induced p65 nuclear translocation in RAW264.7 cells in the presence or absence of PYK2 expression, we first examined this event in RAW264.7 cells transiently transfected with control and miRNA-PYK2. The miRNA-PYK2 generated was able to inhibit PYK2 expression specifically and efficiently in PYK2-expressed Cos-7 cells (Fig. 5A) and in macrophages (RAW264.7; Fig. 5B). Immunostaining analysis demonstrated that p65 was localized mainly at the cytoplasm or associated with nuclei membrane in RAW264.7 cells without stimulation. Upon treatment with LPS for 15 min, p65 was distributed mainly in the nuclei (Fig. 5C), suggesting a nuclei translocation. When cells expressed miRNA-PYK2 (indicated by GFP), LPS-induced p65 nuclear translocation was attenuated (Fig. 5, C and D), suggesting a role of PYK2 in this event. To verify this view further, we used the stable PYK2 shRNA-expressing cell lines to test LPS- and PGN-induced p65 nuclear translocation. As shown in Figure 6, LPS- and PGN-induced p65 nuclear translocation was abolished or reduced in PYK2-shRNA cells. Together, these results suggest that PYK2 appeared to be required for LPS- and PGN-induced p65 nuclear translocation, an event important for NF-κB-activated gene expression.

Figure 5.

Reduced LPS-induced p65 nuclear translocation in RAW264.7 cells expressing miRNA-PYK2. (A) Western blot analysis showing PYK2 expression in Cos-7 cells cotransfected with indicated plasmids. Note that miRNA-PYK2-2 specifically suppresses exogenous PYK2 expression. (B) Immunostaining analysis of endogenous PYK2 in RAW264.7 cells transfected with the scramble and miRNA-PYK2-2. RAW264.7 cells expressing the miRNA plasmid, which encodes GFP as an indicator, were fixed and immunostained with anti-PYK2 antibody (monoclonal; red). Open arrows indicate control GFP expression cells, and filled arrows indicate reduced PYK2 expression in miRNA-PYK2-transfected cells. (C) LPS (1 μg/ml)-induced p65 nuclear translocation in RAW264.7 cells expressing with (filled arrows) or without (open arrows) miRNA-PYK2 were examined by immunostaining analysis using indicated antibodies. Original marker bars, 20 μm. DAPI, 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole. (D) Quantification analysis of data from C. The ratio of p65 immunofluorescence intensity in nuclei over cytoplasm was presented as means ± sd (n=10). *, P < 0.01, in comparison with cells without miRNA-PYK2 expression.

Figure 6.

Impaired LPS- and PGN-induced p65 nuclear translocation in PYK2-deficient RAW264.7 cell lines. (A) Immunofluorescene analysis of p65 distribution in the control and PYK2-shRNA cell lines stimulated without (Control) or with LPS (1 μg/ml, 20 min) or PGN (10 ng/ml, 20 min). Original marker bar, 20 μm. Open arrows indicate p65 staining at the cytoplasm, and filled arrows indicate p65 distribution at the nuclei. (B) Quantification analysis of data from A. The ratio of p65 immunofluorescence intensity in nuclei over cytoplasm was presented as means ± sd (n=10). *, P < 0.01, in comparison with the control cells without LPS/PGN stimulation.

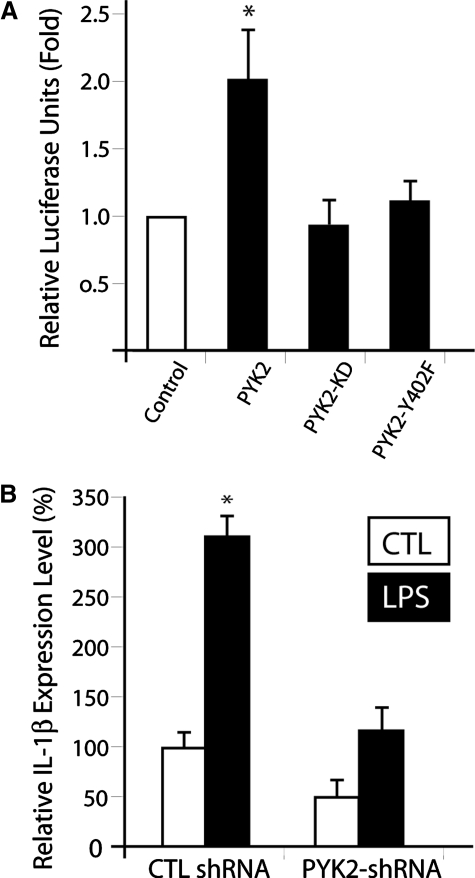

We next examined whether NF-κB-dependent gene transcription is regulated by PYK2. To this end, a NF-κB-dependent luciferase reporter assay was first carried out in RAW264.7 cells cotransfected with the reporter plasmid with or without PYK2. Cells expressing wild-type PYK2 exhibit an approximate twofold increase of the luciferase activity (Fig. 7A). However, cells expressing catalytic, inactive mutants (e.g., PYK2-KD and PYK2-Y402F) failed to induce this activity (Fig. 7A). To determine if PYK2 is required for LPS-induced and NF-κB-dependent gene expression, we examined IL-1β, a cytokine whose expression depends on NF-κB activation, expression in the control, and PYK2 shRNA cell lines. Real-time PCR analysis demonstrated that LPS was able to induce IL-1β expression in the control cells (Fig. 7B); however, this induction was abolished in PYK2 shRNA cells (Fig. 7B). Thus, these results support a role for PYK2 in LPS-induced, NF-κB-dependent gene expression.

Figure 7.

PYK2 regulation of NF-κB promoter activity and NF-κB-dependent IL-1β expression. (A) PYK2 is sufficient to activate NF-κB promoter. (B) PYK2 is necessary for LPS-induced, NF-κB-dependent IL-1β expression. (A) RAW264.7 cells were transiently transfected with PYK2 or PYK2 mutants with NF-κB-luciferase and β-galactosidase. (B) Control and PYK2-shRNA-expressing RAW264.7 cells were stimulated with or without LPS (1 μg/ml, 1 h). The mRNAs from treated cells were analyzed by real-time PCR for gene expression of IL-1β. The values displayed are combined from at least three separate experiments and are expressed as fold increase over the control (β-actin). PYK2, but not PYK2 mutants, increases luciferase production, illustrated in A. LPS induces IL-1β production in the control, but not PYK2-shRNA cells, illustrated in B. *, P < 0.01, in comparison with the control vector (A) or control without LPS stimulation (B).

DISCUSSION

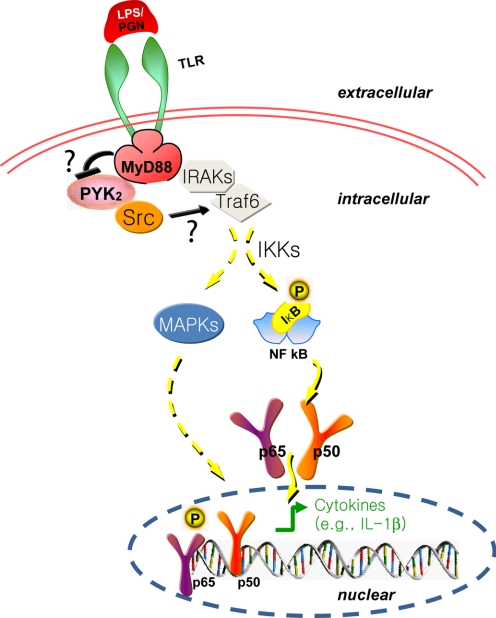

Our studies provide evidence that PYK2 regulates LPS-induced NF-κB activation and signaling and suggest a new insight into the mechanism by which PYK2 regulates an innate immune response. These results lead to a working hypothesis depicted in Figure 8. According to this model, PYK2 interacts with MyD88 and regulates LPS-induced phosphorylation and degradation of IκB, thus NF-κB nuclear translocation and activation. Via nuclear NF-κB activation, PYK2 may regulate transcriptional expression of inflammatory genes, such as IL-1β.

Figure 8.

A working hypothesis for PYK2 regulation of LPS/PGN-induced NF-κB activation by its interaction with MyD88.

In this model, we also speculate that MyD88 may be a negative modulator of PYK2 kinase. The interaction of MyD88 with PYK2 may prevent PYK2 from constitutive active and keep PYK2 autophosphorylation as a transient event. This view is supported by our observations that whereas MyD88-PYK2 interaction requires PYK2 kinase activation (Fig. 1B), MyD88 appears to suppress PYK2 autophosphorylation sufficiently (Fig. 2B). The transient time course of PYK2 activation may play a role for LPS-induced transient (5–30 min) phosphorylation of IκB. The impaired time course of phosphorylation of IκB in PYK2-deficient cells in response to LPS (Fig. 4B) supports this view.

PYK2 appears to serve as a modulator/integrator of multiple signaling pathways. It is activated in response to cell adhesion, oxidative stress, and cytokine stimulation. It is involved in cell adhesion, spreading, and migration of hematopoietic cells, including monocyte/macrophage, neutrophil, and T/B cells. Thus, it is likely to be involved in vivo for recruitment of monocytes/neutrophil to sites of inflammation. The present study that demonstrates PYK2 involvement in LPS signaling may provide additional support for an important effect of PYK2 in innate immune response and in pathologically inflammatory-associated disorders. Our studies are also in line with recent findings that PYK2 mediated LPS-induced IL-8 expression in human endothelial cells [22].

Our data that PYK2 interacts with MyD88 may provide an important mechanism underlying PYK2 regulation of LPS signaling. MyD88, an essential adaptor protein, recruits the IRAK to the TLR receptor complex, leading to IκB phosphorylation and degradation and NF-κB activation. Thus, via MyD88, PYK2 may regulate IκB phosphorylation and degradation, subsequently, nuclear translocation, and activation of NF-κB. MyD88 recruitment to the plasma membrane and MyD88 phosphorylation are necessary for its activation [3]. We thus speculate that the PYK2-MyD88 interaction may be an important event for the regulation of both processes involved in MyD88 activation (MyD88 phosphorylation and MyD88 recruitment to the plasma membrane). This speculation is in line with the observations that LPS activates PYK2 and Src tyrosine kinases [22] (Fig. 3D) and increases PYK2 interaction with MyD88 (Figs. 1B and 3C), MyD88 is tyrosine-phosphorylated upon PYK2/Src activation (Fig. 1D), and PYK2 regulates phosphoinositol signaling, which is required for MyD88 activation [3]. Note that MyD88-dependent, LPS-induced IL-6 secretion by human and murine fibroblasts requires the presence of FAK [23], consistent with our view that MyD88 may be an important link for FAK/PYK2 family kinases to regulate LPS signaling and inflammatory response.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (to L. M.; AR048120 to W-C. X.).

Footnotes

Abbreviations: DD=death domain, FAK=focal adhesion kinase, HEK=human embryonic kidney, ID=intermediary domain, IKK=IκB kinase, IRAK=IL-1R-associated kinase, miRNA=micro RNA, MyD88-Fl=MyD88 full length, NP-40=Nonidet P-40, PGN=peptidoglycan, PY402=PYK2 autophosphorylation at tyrosine 402, PYK2=proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2, RIPA=radioimmunoprecipitation assay, shRNA=short hairpin RNA, TIR=Toll/IL-1R, TIRAP=TIR domain-containing adaptor protein, TRAF6=TNFR-associated factor 6

References

- Li X, Qin J. Modulation of Toll-interleukin 1 receptor mediated signaling. J Mol Med. 2005;83:258–266. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0622-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson D J, Currie A J, Bowdish D M, Brown K L, Rosenberger C M, Ma R C, Bylund J, Campsall P A, Puel A, Picard C, Casanova J L, Turvey S E, Hancock R E, Devon R S, Speert D P. IRAK-4 mutation (Q293X): rapid detection and characterization of defective post-transcriptional TLR/IL-1R responses in human myeloid and non-myeloid cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:8202–8211. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.8202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill L A, Bowie A G. The family of five: TIR-domain-containing adaptors in Toll-like receptor signaling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:353–364. doi: 10.1038/nri2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakoff-Nahoum S, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrc2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moynagh P N. The Pellino family: IRAK E3 ligases with emerging roles in innate immune signaling. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang C H, Silvis C, Deshpande N, Nystrom G, Frost R A. Endotoxin stimulates in vivo expression of inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor α, interleukin-1β, -6, and high-mobility-group protein-1 in skeletal muscle. Shock. 2003;19:538–546. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000055237.25446.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Bloom O, Zhang M, Vishnubhakat J M, Ombrellino M, Che J, Frazier A, Yang H, Ivanova S, Borovikova L, Manogue K R, Faist E, Abraham E, Andersson J, Andersson U, Molina P E, Abumrad N N, Sama A, Tracey K J. HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science. 1999;285:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Henn H, Destaing O, Sims N A, Aoki K, Alles N, Neff L, Sanjay A, Bruzzaniti A, De Camilli P, Baron R, Schlessinger J. Defective microtubule-dependent podosome organization in osteoclasts leads to increased bone density in Pyk2(−/−) mice. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:1053–1064. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff M, Jurdic P. Podosomes in osteoclast-like cells: structural analysis and cooperative roles of paxillin, proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (Pyk2) and integrin αVβ3. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2775–2786. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.15.2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure C, Corvol J C, Toutant M, Valjent E, Hvalby O, Jensen V, El Messari S, Corsi J M, Kadare G, Girault J A. Calcineurin is essential for depolarization-induced nuclear translocation and tyrosine phosphorylation of PYK2 in neurons. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:3034–3044. doi: 10.1242/jcs.009613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Lu W, Ali D W, Pelkey K A, Pitcher G M, Lu Y M, Aoto H, Roder J C, Sasaki T, Salter M W, MacDonald J F. CAKβ/Pyk2 kinase is a signaling link for induction of long-term potentiation in CA1 hippocampus. Neuron. 2001;29:485–496. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00220-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duong L T, Nakamura I, Lakkakorpi P T, Lipfert L, Bett A J, Rodan G A. Inhibition of osteoclast function by adenovirus expressing antisense protein-tyrosine kinase 2. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7484–7492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008368200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avraham H, Park S Y, Schinkmann K, Avraham S. RAFTK/Pyk2-mediated cellular signaling. Cell Signal. 2000;12:123–133. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(99)00076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakkakorpi P T, Bett A J, Lipfert L, Rodan G A, Duong le T. PYK2 autophosphorylation, but not kinase activity, is necessary for adhesion-induced association with c-Src, osteoclast spreading, and bone resorption. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11502–11512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206579200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong W, Parsons J T. Induction of apoptosis after expression of PYK2, a tyrosine kinase structurally related to focal adhesion kinase. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:529–539. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.2.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X J, Wang C Z, Dai P G, Xie Y, Song N N, Liu Y, Du Q S, Mei L, Ding Y Q, Xiong W C. Myosin X regulates netrin receptors and functions in axonal path-finding. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:184–192. doi: 10.1038/ncb1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Han J Y, Xi C X, Xie J X, Feng X, Wang C Y, Mei L, Xiong W C. HMGB1 regulates RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis in a manner dependent on RAGE. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1084–1096. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X R, Du Q S, Huang Y Z, Ao S Z, Mei L, Xiong W C. Regulation of CDC42 GTPase by proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 interacting with PSGAP, a novel pleckstrin homology and Src homology 3 domain containing rhoGAP protein. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:971–984. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.5.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Takeda K, Akira S. TIR domain-containing adaptors define the specificity of TLR signaling. Mol Immunol. 2004;40:861–868. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S, Cho H H, Joo H J, Bae Y C, Jung J S. Role of MyD88 in TLR agonist-induced functional alterations of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;317:143–150. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9842-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi O, Akira S. Toll-like receptors; their physiological role and signal transduction system. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:625–635. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand A R, Cucchiarini M, Terwilliger E F, Ganju R K. The tyrosine kinase Pyk2 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-8 expression in human endothelial cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:5636–5644. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisel M B, Druet V A, Sibilia J, Klein J P, Quesniaux V, Wachsmann D. Cross talk between MyD88 and focal adhesion kinase pathways. J Immunol. 2005;174:7393–7397. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]