Abstract

The stimulation of DC by CD4+ T cells is known to condition DC to activate naïve CD8+ T cells, predominantly via CD40-CD40L interactions. It has been proposed that a critical consequence of DC conditioning is the induction of CD70 expression. Whether and how CD70 induction contributes to CD8+ T cell responses in the absence of CD40-CD40L interactions are unknown. CD8+ T cell responses to adenoviral- or DC-based immunization of CD40-deficient mice revealed a CD40-independent, CD4+ T cell-dependent pathway for CD70 induction on conventional DC. This pathway and subsequent CD8+ T cell responses were enhanced by, but not dependent on, concomitant activation of TLR and in part, used TRANCE and LIGHT/LTαβ stimulation. Blocking TRANCE and LIGHT/LTαβ during stimulation reduced the immunogenicity of CD40-deficient DC. These data support the hypothesis that induction of CD70 expression on DC after an encounter with activated CD4+ T cells is a major component of CD4+ T cell-mediated licensing of DC. Further, multiple pathways exist for CD4+ T cells to elicit CD70 expression on DC. These data in part explain the capacity of CD40-deficient mice to mount CD8+ T cell responses and may provide additional targets for immunotherapy in situations when CD40-mediated licensing is compromised.

Keywords: costimulation, cell differentiation, cell-surface molecules

Introduction

The molecular basis by which CD4+ T cells operate during the activation of primary CD8+ T cell responses is thought to be the provision of CD154 (CD40L) to DC. Although not always required for CD8+ T cell responses to pathogens [1], CD40L-mediated stimulation of DC “conditions” DC to elicit CD8+ T cell responses to tissue-derived antigens [2,3,4]. This capacity for CD40L-mediated costimulation to initiate CD8+ T cell responses has led to intensive investigation into the functional differences exhibited by DC after CD40 engagement, which could account for their ability to elicit a primary CD8+ T cell response. Among possible candidates, subsets of DC have been shown to express the proinflammatory cytokine IL-12p70 after CD40 engagement. IL-12 has been proposed to serve as a third signal necessary for the full activation of naïve CD8+ T cells [5]. More recently, evidence has implicated the expression of CD70 as an important component of a conditioned DC.

In several different systems in which direct CD40 stimulation replaces the necessity for CD4+ T cells in helper-dependent CD8+ T cell responses, blockade of CD70-mediated costimulation ablates the primary CD8+ T cell response [6,7,8]. Further, treatment of mice with recombinant soluble CD70 can replace the necessity for conditioning DC to elicit primary CD8+ T cell responses to the OVA257 peptide [9]. More recently, induced expression of transgenic CD70 on DC has been shown to be sufficient to initiate primary CD8+ T cell responses and even reactivate tolerized CD8+ T cells [10]. Together, these data implicate CD70 as an important third signal costimulatory molecule that is expressed by conditioned DC and supports primary CD8+ T cell responses. Thus, understanding the mechanism by which CD70 is induced on DC in vivo has become an area of emphasis for vaccine development.

Although the expression of CD70 on cultured, semi-mature BMDC is achievable in vitro by TLR ligands [7, 11] or stimulation of CD40 [6, 7, 11], the molecular mechanisms accounting for CD70 induction on DC in vivo remain relatively unexplored. The predominance of recent data has indicated that CD70 expression is induced in vivo by CD40 engagement with varying degrees of requirement for concomitant TLR engagement [6, 8, 12]. Thus, it might be predicted that CD40-independent CD8+ T cell responses are independent of CD70-mediated costimulation or that CD40-independent mechanisms exist for inducing CD70 on DC in vivo [13]. Here, we demonstrate that CD40-independent CD8+ T cell responses are CD70-dependent and that CD70 expression and DC immunogenicity arise as a consequence of alternative mechanisms of licensing DC by CD4+ T cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

B6 mice were obtained from Taconic (Germantown, NY, USA). CD40-deficient mice (B6.129P2-Cd40tm1Kik/J, Stock #002928) and CD40L-deficient mice (B6.129S2-Cd40lgtm1Imx/J, Stock #002770) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). OT-II TCR transgenic mice (expressing TCR specific for H2-Kb-OVA257 or H2-IAb-OVA323 complexes, respectively) were used with permission from Dr. Francis Carbone (University of Melbourne, Australia). MyD88-deficient mice were provided by Dr. Eric Pamer (Memorial Sloan Kettering, New York, NY, USA) with the permission of Dr. Shizuo Akira (Osaka University, Japan). CD40L-deficient OT-II were generated by intercrossing the two strains and screening progeny for the expression of Vα2+Vβ5+ CD4+ T cells by flow cytometry of blood samples and PCR-mediated genotyping for the absence of CD40L. Mice were maintained in specific pathogen-free facilities and were treated in accordance with the guidelines established by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Virginia (Charlottesville, VA, USA).

Cell lines and viruses

Recombinant OVA-adeno was kindly provided by Dr. Young Hahn (University of Virginia) and was propogated on 293A fibroblasts.

Peptides

Synthetic peptides were made by standard Fmoc chemistry using a model AMS422 peptide synthesizer (Gilson Co. Inc., Middleton, WI, USA) in the Biomolecular Core Facility at the University of Virginia. All peptides were purified to >98% purity by reverse-phase HPLC on a C-8 column (Vydac, Hesperia, CA, USA). Purity and identity were confirmed using a triple-quadruple mass spectrometer (Finnigan, San Jose, CA, USA). Postsynthesis, the endotoxin was removed by the Detoxi-Gel endotoxin removal kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA).

DC

Ex vivo DC were separated from lymph nodes or spleens after Collagenase D/DNase (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) digestion of minced organs in Clicks media (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA), as described previously [8]. Digests were quenched in 0.1 M EDTA in PBS, then converted to single-cell suspensions by mashing through 100 μm nylon mesh (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA), washed with 5 mM EDTA in Clicks media, and isolated by centrifugation on Lympholyte-M.

In vitro maturation of DC

Spleen/lymph node suspensions (1.6×106) were cocultured with 5 × 105 enriched OT-II cells in the presence of 1 μg/ml OVA323 (ISQAVHAAHAEINEAGR) or HBC128 (TPPAYRPPNAPIL) for 24–48 h in 48-well tissue-culture plates (Costar, Corning, NY, USA). In some cultures, blocking antibodies to CD40L (clone MR1, provided by Dr. Randy Noelle, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA), TRANCE (clone IKK22-5, provided by Hideo Yagita, Juntendo University, Japan [14]), LAG-3 (clone eBioC9B7W, eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), LTβR-Ig (provided by Dr. Yang-Xin Fu, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA), or combinations thereof were included at 10 μg/ml. DC were characterized by costaining with antibodies against the following molecules, conjugated as indicated: CD19-APC-Cy7, CD11c-APC, CD11b-PE-Cy7, CD8α-PerCP, CD86-FITC, CD70-PE, or isotype control PE. Gating was determined by fluorescence minus one panels, in which cells were stained with the full panel of antibodies minus anti-CD86 or anti-CD70. All fluorescent antibodies were purchased from eBioscience, except CD8α-PerCP, which was obtained from Becton Dickinson. Stained samples were collected with Dako Cyan or BD FACSCanto cytometers and analyzed by FlowJo software (TreeStar, Eugene, OR, USA).

In vivo maturation of DC

Mice received 3 × 106 OT-II CD4+ T cells, which had been magnetically enriched by negative selection (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA), and 500 μg OVA323 or HBC128 via i.v. injection, as described previously [15]. Some mice received 50 μg PAM3CSK4 (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA) via i.p. injection. Forty-eight hours after injection, spleens and lymph nodes were harvested and DC isolated for staining as described above.

Immunization

Recombinant OVA-adeno (2×108) PFU was injected i.v. for the generation of primary CD8+ T cell responses. BMDC were cultured for 18 h with 10 μg/ml OVA323 or no peptide and positively enriched (Miltenyi Biotec) OT-II CD4+ T cells. BMDC were then isolated from cultures by negative selection using StemSep columns to remove T cells. Enriched BMDC (95% pure, no CD4+ T cells) were pulsed further with 10 μg/ml OVA257 (SIINFEKL) peptide for 4 h at 37°C in HBSS containing 5% FBS and 5 μg/ml human β2 microglobulin (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA), washed twice, and resuspended in HBSS. Alternatively, conventional DC were enriched from short-term (48 h) cocultures of OT-II CD4+ T cells and B6 or CD40– splenocytes, as described above. Mice received i.v. injections of 105 peptide-pulsed DC. In some cases, DC were incubated for 3 h with 10 μg/ml anti-CD70 [16] or isotype-matched control antibody rat IgG2b (eBioscience) prior to washing and immunization. Alternatively, B6 or CD40-deficient mice received 3 × 106 magnetically enriched OT-II cells and were immunized i.v. with 50 μg OVA257 peptide with 500 μg OVA323 or HBC128 peptide. CD40-deficient mice received 500 μg anti-CD70 or cIg i.p. on Days 0 and 2. In both cases, primary CD8+ T cells were assessed 7 days after immunization by MHC-tetramer staining.

Tetramer staining

Dr. Vic Engelhard (University of Virginia) provided H2-Kb-tetramers, which had been folded around OVA257. Lymphocytes were isolated from perfused lungs on nycodenz gradients after collagenase, hyaluronidase, and DNase digestion, as described previously [17], or from homogenized spleens. Enriched T cells were coincubated for 30 min at 4°C with tetramer-APC, anti-CD8-PerCP, and anti-CD44-PE. Staining was assessed by flow cytometry as above. Nonspecific staining values of CD8+ T cells from mice immunized with irrelevant antigen were subtracted.

Statistics

Statistical significance of differences between comparison groups was determined by performing unpaired two-tailed Student t-tests for 95% confidence limits using GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA, USA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

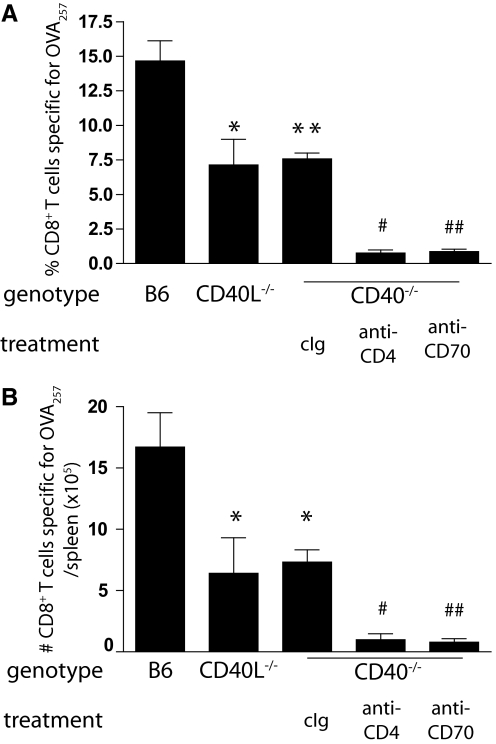

CD70-dependent, CD40-independent CD8+ T cell responses to adenovirus infection

i.v. immunization of B6 mice with 2 × 108 PFU recombinant OVA-adeno generates a potent CD8+ T cell response, peaking 7 days after infection, that is specific for the immunodominant OVA257–264 epitope (OVA257). This response was significantly dependent on CD40-CD40L interactions, as mice deficient in either of these molecules generated a primary CD8+ T cell response specific for OVA257 that was reduced by ∼50% compared with wild-type (Fig. 1). To determine the extent to which CD70-mediated costimulation is required for the CD40-independent primary CD8+ T cell response, CD40-deficient mice were immunized with OVA-adeno and treated with FR70, a blocking, nondepleting antibody to CD70 [8, 16, 18]. In comparison with control-treated mice, the frequency and number of OVA257-specific CD8+ T cells in the primary response were strongly inhibited by blocking CD70 (Fig. 1). Thus, primary CD8+ T cell responses to adenovirus can be generated in a CD40-independent, CD70-dependent manner. We next asked whether CD4+ T cell-dependent or -independent mechanisms were responsible for the primary CD8+ T cell response in the CD40-deficient mice. In the absence of CD4+ T cells, the primary CD8+ T cell response was absent almost completely from CD40-deficient mice (Fig. 1, A and B). Together, these data indicated that CD4+ T cells can induce a CD70-dependent CD8+ T cell response to OVA-adeno that is independent of CD40-CD40L interactions.

Figure 1.

CD40-independent CD8+ T cell responses are dependent on CD70 and CD4+ T cells. (A) Wild-type B6, CD40−/−, and CD40L−/− mice were injected i.v. with 2 × 108 PFU of OVA-adeno. CD40−/− mice were treated with cIg, anti-CD4, or anti-CD70 as described in Materials and Methods. Seven days later, the magnitude of the primary CD8+ T cell response was assessed, staining splenocytes from infected mice with anti-CD8, anti-CD44, and OVA257-tetramer. (B) Number of OVA257-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleens of the indicated mice immunized and treated as described in A. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, compared with B6; #, P < 0.05; ##, P < 0.01, compared with cIg-treated CD40−/−. The experiments were performed twice with similar results.

Several lines of evidence have demonstrated that CD40-CD40L signaling serves as the major conduit by which activated CD4+ T cells condition DC [2, 4, 19]. However, sufficient evidence exists to indicate that DC can be activated in CD40-CD40L-independent manners. First, previous studies have shown that CD40L-deficient mice can mount productive primary anti-viral CD8+ T cell responses [20], a fact reiterated using adenovirus in the current study. Second, studies have demonstrated directly that DC can be activated independently of CD40-CD40L [21, 22]. Our data indicate that CD4+ T cells are the primary source of this alternative, CD70-dependent licensing mechanism for adenovirus infections, although this is clearly not the only alternative mechanism available, as a variety of pathogens can elicit primary CD8+ T cell responses in the absence of CD4+ T cells [23]. Whether the stimuli that operate to support helper-independent CD8+ T cell responses work via the induction of CD70 is not known; however, CD70 has been shown to play an important role in the generation of primary CD8+ T cell responses to many of these helper-independent pathogens [18].

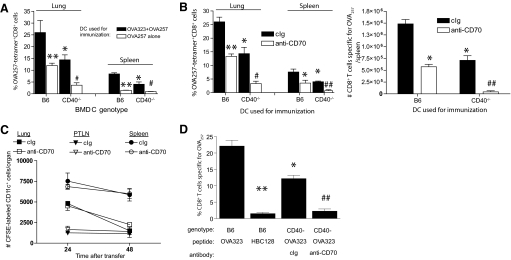

Immunogenicity of DC licensed by CD4+ T cells can be independent of CD40 but remains dependent on CD70

The preceding data strongly suggested that in the absence of CD40-CD40L interactions, CD4+ T cells can induce CD70-dependent, primary CD8+ T cell responses. To confirm this possibility in the absence of the inflammation that is concomitant with infection, we used an adoptive transfer system and DC-based immunization. Enriched OT-II CD4+ T cells were cocultured in the presence or absence of OVA323 peptide with BMDC generated from wild-type or CD40-deficient mice. After 24 h, BMDC were isolated from the cultures, pulsed with OVA257 peptide, and used to immunize wild-type B6 mice. A significantly greater frequency of OVA257-specific CD8+ T cells was in the cohorts of mice that had received BMDC from wild-type mice cultured in the presence of OVA323 and OT-II CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2A), indicating that further conditioning of BMDC by OT-II cells augments their immunogenicity. The addition of OVA323 to the in vitro cultures was not absolutely required for the immunogenicity of OVA257-pulsed B6 BMDC, presumably as BMDC present MHC class II-restricted peptides derived from xeno-antigens acquired during culture. In contrast, BMDC from CD40-deficient mice cultured in the absence of OVA323 were minimally immunogenic. BMDC from CD40-deficient mice that were cultured in the presence of OVA323 consistently elicited OVA257-specific CD8+ T cell responses that were of approximately half the magnitude of that induced by CD40-replete BMDC (Fig. 2A). Importantly, the primary CD8+ T cell response generated in B6 mice by CD40-deficient, OT-II activated BMDC was eliminated mostly when the BMDC were treated with blocking anti-CD70 antibody prior to immunization. This confirmed that CD70 is a critical costimulatory molecule for primary CD8+ T cell responses, even in the absence of CD40-mediated conditioning of DC (Fig. 2B). Pretreatment with anti-CD70 did not lead to accelerated loss of transferred BMDC (Fig. 2C), indicating that the reduction in the primary CD8+ T cell is a result of prevention of costimulation, rather than enhanced clearance of antigen. Further, treatment with anti-CD70 did not alter the kinetics of the primary CD8+ T cell response to OVA-adeno or BMDC immunization (not shown).

Figure 2.

DC activated independently of CD40-CD40L are dependent on CD70 for immunogenicity. BMDC generated from wild-type or CD40−/− mice were cococultured with OT-II CD4+ T cells for 48 h in the presence or absence of 10 μg/ml OVA323. (A) Immunogenicity of wild-type and CD40−/− BMDC. Enriched BMDC from OT-II cocultures containing OVA323 (solid bars) or no peptide (open bars) were pulsed with 10 μg/ml OVA257 peptide and 1 × 105 used to immunize B6 mice. Seven days after immunization, lungs or spleen from mice were harvested and stained for OVA257-specific CD8+ T cells. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, compared with B6 cultures containing OVA323; #, P < 0.05, compared with CD40−/− DC cocultured with OVA323. (B) Blockade of CD70 on CD40-independently activated BMDC minimizes immunogenicity. BMDC, derived as above, were pulsed with OVA257 and 100 μg/ml cIg (solid bars) or anti-CD70 (open bars) for 2 h, and 1 × 105 were injected i.v. into B6 mice. The frequency (upper panel) and number (lower panel) of OVA257-specific CD8+ T cells in the lungs (upper panel) and spleen (upper and lower panels) 7 days after immunization were determined by CD8 and MHC-tetramer staining. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, compared with B6 BMDC pulsed with cIg; #, P < 0.05; ##, P < 0.01, compared with CD40−/− BMDC pulsed with cIg. (C) Anti-CD70 treatment does not enhance clearance of BMDC. CFSE-labeled BMDC (2×105) were treated with cIg or anti-CD70 and transferred into B6 recipients. The number of CFSE+CD11c+ DC was counted at 24 h and 48 h. Experiments were repeated once with equivalent results. PTLN, Paratracheal lymph node. (D) Frequency of OVA257-specific CD8+ T cell response in lungs of B6 or CD40−/− mice that received OT-II cells and then immunized with OVA323 and OVA257. CD40-deficient mice received cIg or anti-CD70 (500 μg i.p.) as indicated. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, compared with B6 mice receiving OVA323; ##, P < 0.01, compared with CD40−/− mice receiving OVA323 and cIg.

To determine whether DC in vivo were similarly immunogenic in the absence of CD40 stimulation, OT-II T cells were transferred into wild-type or CD40-deficient mice. Recipient mice were immunized with endotoxin-free OVA257 and OVA323 peptide or an irrelevant class II-restricted peptide derived from HBC128 antigen, and the magnitude of the OVA257-specific response was assessed 7 days later by MHC-tetramer staining. Consistent with previous reports, the OVA257-specific CD8+ T cell responses in CD40-deficient mice were significantly lower than observed in B6 mice but clearly discernable (Fig. 2C). The requirement for CD70 costimulation in the generation of the primary CD8+ T cell response was nearly absolute, as the response was nearly completely ablated by injection of a CD70-blocking antibody (Fig. 2C).

Of note, the magnitude of the primary CD8+ T cell response elicited by CD40-deficient DC, even after activation by CD4+ T cells, was substantially lower than that achieved by CD40-replete DC, confirming a significant but not obligatory role for CD40 in primary CD8+ T cell responses to DC immunization [24]. The reduction in immunogenicity of DC in the absence of CD40-CD40L interactions may well be a result of differences in the relative levels or duration of CD70 expression. However, the fact that anti-CD70 only blocks ∼50% of the primary response to DC immunization in B6 mice, yet nearly 100% of the response in CD40-deficient mice, strongly suggests that there is a CD40-dependent, alternative third signal available, aside from CD70.

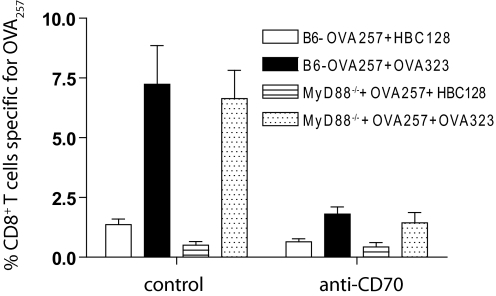

As it was formally possible that the peptides used for immunization were contaminated with PAMPs, which remained after endotoxin removal, we examined whether CD40-CD40L-independent, CD70-dependent responses were maintained in MyD88-deficient mice. Thus, CD40L-deficient OT-II cells were transferred into MyD88-deficient or wild-type mice and challenged with OVA257 and OVA323 or HBC128. MHC-tetramer staining 7 days later revealed no significant differences in the magnitude of the response between MyD88-deficient mice and wild-type, which received OVA257 and OVA323, and the OVA257-specific CD8+ T cell response was minimal in HBC128-primed mice (Fig. 3). Antibody-mediated blockade of CD70 again ablated the primary CD8+ T cell response (Fig. 3). Thus, CD4+ T cells possess a mechanism(s) to license CD8+ T cell responses that is independent of CD40-CD40L and does not require MyD88-mediated stimulation.

Figure 3.

CD40L-independent licensing of CD8+ T cell responses to peptide does not require MyD88-mediated stimulation. B6 or MyD88-deficient mice received CD40L-deficient OT-II cells and were challenged with OVA257 and HBC128 or OVA323 and cIg or anti-CD70. The magnitude of CD8+ T cell response to OVA257 was determined by MHC-tetramer and CD8 staining of splenocytes 7 days later. The experiment was repeated twice.

Activated CD4+ T cells can induce expression of CD70 on conventional DC in the absence of CD40-CD40L interactions

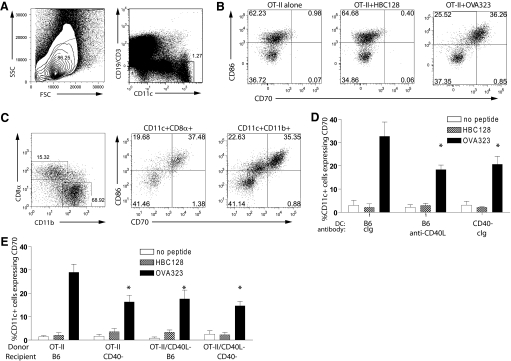

As the CD8+ T cell responses generated in CD40-deficient environments were highly dependent on CD70, we sought direct evidence that CD4+ T cells can use CD40L-independent mechanisms to induce CD70 expression on DC. Initially, OT-II CD4+ T cells were cocultured with splenocytes from B6 mice and HBC128 or OVA323 peptide. CD70 was induced on conventional CD11c+, CD19/CD3− DC only in cultures containing OT-II and OVA323 (Fig. 4B). To exclude the possibility of a third cell being responsible for the up-regulation of CD70 on DC after coincubation with activated CD4+ T cells, enriched OT-II (95% pure) cells were cocultured with positively selected DC (90% pure) in the presence of OVA323. Under these conditions, we found CD70 expression induced on CD8α+ and CD11b+ DC (Fig. 4C). We examined the relative contribution of CD40-CD40L stimulation to CD70 expression by performing similar cultures in the presence of anti-CD40L (MR1) antibody or cIg. The presence of the CD40L-blocking antibody only reduced CD70 expression on DC in the cultures by ∼30% (Fig. 4D). To ascertain whether the remaining expression of CD70 was a result of inefficient blocking by the anti-CD40L antibody, similar cultures were established using CD40-deficient splenocytes. Again, although a reduction in CD70 expression was observed, a significant amount of CD70 expression was induced on DC in the absence of CD40 (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

CD4+ T cells can induce CD70 expression on conventional DC independently from CD40-CD40L stimulation. (A) Flow cytometry gating strategy for DC; live lymphocytes were further negatively gated for CD19 and CD3 and positively gated for CD11c expression. SSC, Side-scatter; FSC, forward-scatter. (B) Specific induction of CD70 on DC. In vitro cultures were established with enriched OT-II CD4+ T cells and splenocytes/lymph node cells with OVA323 peptide or HBC128. Forty-eight hours later, cultures were analyzed by flow cytometry for the up-regulation of CD86 and CD70 on CD11c+ cells. (C) Direct induction of CD70 expression on DC by CD4+ T cells. Enriched OT-II CD4+ T cells were cultured with purified DC and OVA323 peptide. (Left panel) Identification of conventional DC subsets by expression of CD8α or CD11b. (Middle and right panels) Expression of CD86 and CD70 on conventional DC subsets. (D) CD70 induction without CD40-CD40L stimulation. Cultures of OT-II cells and B6 or CD40-deficient splenocytes were established with OVA323 or HBC128. Cultures with B6 splenocytes included cIg or anti-CD40L (100 μg/ml). *, P < 0.05, comparing OVA323-induced responses and HBC128-induced responses. (E) B6 or CD40-deficient mice received OT-II or CD40L-deficient OT-II CD4+ T cells and were challenged with PBS, HBC128, or OVA323 peptide (500 μg). Expression of CD70 on CD3/CD19−CD11c+ DC was determined 48 h later. Data in quadrants indicate percentage of CD3/CD19−CD11c+ cells staining with CD70. *, P < 0.05, comparing OVA323-induced responses and HBC128-induced responses. Data are representative of three similar experiments.

We next determined whether CD4+ T cells could elicit CD40L-CD40-independent CD70 expression on DC in vivo. OT-II or CD40L-deficient OT-II CD4+ T cells were transferred into B6 or CD40-deficient recipients and activated by injection of OVA323 or HBC128. Although the strongest CD70 expression was observed in B6 mice that received CD40L-expressing OT-II, CD70 expression was observed consistently in mice that received CD40L-deficient OT-II or were deficient in CD40-expression or both (Fig. 4E). Little CD70 was induced when HBC128 peptide was used instead of OVA323 (Fig. 4E) or when mice did not receive OT-II (not shown). Thus, CD4+ T cells can induce CD70 expression on DC without using the CD40-CD40L stimulatory pathway.

The stimulation requirements for CD70 induction on DC have proven varied. Initial studies by us [7] and others [6, 11] using BMDC, which represent a partially mature DC population, suggested that TLR or CD40-mediated stimulation was sufficient for CD70 expression. More recently, using an agonistic antibody specific for CD40, Sanchez et al. [8] have argued that CD40 engagement is insufficient for CD70 induction on DC in vivo and that concomitant TLR stimulation was required. However, Taraban et al. [6] had reported previously the induction of CD70 expression using anti-CD40 alone, and we have found that stimulation of DC with CD40L-transduced 3T3 cells or soluble CD40L can induce CD70 expression (data not shown), suggesting that strong CD40 stimulation is sufficient for CD70 induction on DC. We find here that activated CD4+ T cells are sufficient for inducing CD70 expression on DC, independent from MyD88-dependent signaling, arguing that TLR-mediated stimulation is not necessary for CD70 induction on DC. However, it is hard to define whether CD4+ T cell-derived, CD40L-mediated stimulation of CD40 on DC is sufficient for CD70 expression, as activated CD4+ T cells express many different molecules (soluble and cell-bound) that could augment CD40L-mediated stimulation, as evidenced by the preceding data, indicating that there is an alternative pathway for CD70 induction by CD4+ T cells in the absence of CD40L-CD40 interactions.

Induction of CD70 expression on DC by activated CD4+ T cells is augmented by TLR engagement but not required

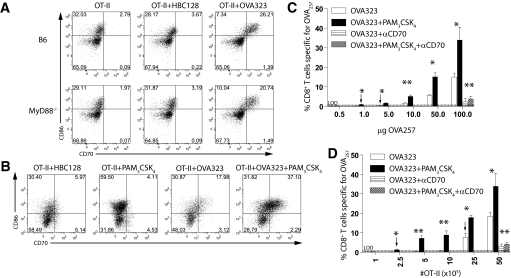

Given the reported role of TLRs for the induction of CD70 expression on DC after stimulation with CD40-specific antibodies [8], we next examined whether TLR-mediated stimulation was required for, or augmented, CD4+ T cell-mediated induction of CD70 expression on DC in vivo. OT-II CD4+ T cells were transferred into recipient wild-type or MyD88-deficient mice and challenged with endotoxin-free OVA323 or HBC128. CD11c+ DC in MyD88-deficient mice up-regulated CD70 expression in response to OVA323 at a similar frequency as seen on DC from B6 mice (Fig. 5A). Further, the intensity of CD70 expression was equivalent in both populations. Thus, the induction of CD70 expression on DC by activated CD4+ T cells is independent of MyD88-mediated stimulation. However, when PAM3CSK4 was injected concurrently with peptide and OT-II cells, a greater proportion of the CD11c+ cells up-regulated CD86 expression and CD70 expression (Fig. 5B). Therefore, we conclude that TLR-mediated stimulation is not required for CD4+ T cells to induce CD70 expression on DC, but it can enhance CD70 expression substantially.

Figure 5.

TLR signals enhance CD70 induction on DC by CD4+ T cells but are not required. (A) Induction of CD70 in vivo does not require MyD88. OT-II were transferred into B6 or MyD88-deficient mice, challenged with HBC128 or OVA23 peptide, and analyzed for CD86 and CD70 expression on CD11c+ cells. Plots are derived from single mice. (B) Enhanced CD70 expression after TLR signaling. OT-II cells were transferred into recipient B6 mice and then challenged with HBC128, PAM3CSK4, OVA323, or OVA323 + PAM3CSK4. Splenocyte populations were stained for CD70 and CD86 expression on CD3/CD19−CD11c+ DC. (C) Concomitant TLR stimulation enhances sensitivity of CD70-dependent CD8+ T cell responses to OVA257. OT-II were transferred into recipient mice and challenged with the indicated amounts of OVA257 and PAM3CSK4 or PBS. The magnitude of the OVA257-specific CD8+ T cell responses was determined by CD8 and MHC-tetramer staining of spleens 7 days later. Anti-CD70-treated mice served as controls (striped and checkered bars, respectively). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, when compared with OVA323 + PAM3CSK4-induced responses. (D) Concomitant TLR stimulation reduces the frequency of CD4+ T cells necessary to support CD8+ T cell response to OVA257. Staggered amounts of OT-II cells were transferred into recipient B6 mice and then challenged with OVA257 and PAM3CSK4 or PBS. Seven days later, OVA257-specific CD8+ T cells were detected in the spleens as described above. Error bars indicate sem of three mice/group. Anti-CD70-treated mice served as controls (striped and checkered bars, respectively). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, when compared with OVA323 + PAM3CSK4-induced responses. Experiments in A and B were repeated three times and C and D twice, with similar results. Dashed line indicates limited detection of significant responses using MHC tetramer (∼0.5%). Arrow indicates data points that are the first at which a significant positive response is detected.

We assessed the impact of TLR-mediated augmentation of CD70 expression by examining CD8+ T cell responses. Thus, cohorts of mice received OT-II CD4+ T cells, OVA323 and staggered amounts of OVA257, and PAM3CSK4 or PBS. The magnitude of the OVA257-specific CD8+ T cell response was determined by MHC-tetramer staining of splenocytes 7 days later. Mice that received PAM3CSK4 in addition to OT-II cells had approximately double the frequency of OVA257-specific CD8+ T cells at high doses of OVA257 (Fig. 5C). In addition, mice receiving PAM3CSK4 and OT-II cells mounted detectable CD8+ T cell responses specific for OVA257 at fivefold lower concentrations of peptide than was required for mice that received OT-II alone (Fig. 5C, compare the two arrows). Finally, we determined whether concomitant TLR signaling reduced the number of OT-II cells that were necessary to obtain CD8+ T cell responses to OVA257 immunization. In mice that received PAM3CSK4, we observed a ten-fold reduction (from 2.5×106 to 2.5×105) in the minimal number of OT-II cells to generate detectable CD8+ T cell responses to OVA257 (Fig. 5D, compare the two arrows). Thus, although not required, the addition of TLR stimulation results in larger CD8+ T cell responses to lower concentrations of peptide and reduces the frequency of coactivated CD4+ T cells necessary to support the CD8+ T cell response.

Although activated CD4+ T cells intrinsically have all of the requisite stimulatory molecules to elicit CD70 expression, a greater incidence of CD70 expression is achieved when TLR agonists are used in parallel. This may be a result of TLR agonists partially maturing DC so that they are more susceptible to CD4+ T cell-mediated stimulation, perhaps by increasing the expression of CD40, or an action of TLR agonists on the CD4+ T cells themselves [25]. Importantly, when TLR were co-targeted, fewer transferred CD4+ T cells were required to elicit a CD8+ T cell response, and CD8+ T cell responses could be generated against smaller amounts of peptide. It is particularly significant to note that incorporation of MHC class II-restricted peptides by themselves was insufficient to license the primary CD8+ T cell response to MHC class I-restricted peptides but that adoptive transfer of >100,000 monospecific CD4+ T cells was also required, indicating that the CD4+ T cell response generated by the MHC class II-restricted peptides is suboptimal (Fig. 5C). Thus, in the absence of CD40-CD40L stimulation or PAMP-mediated activation, the degree of CD4+ T cell activation achieved is insufficient to support the primary CD8+ T cell response. Therefore, augmenting vaccines by co-eliciting CD4+ T cells to support the activation of DC will likely be augmented significantly by the inclusion of innate receptor agonists. Further, a logical extension of these observations is that CD40-CD40L-independent licensing of DC may become more prominent at high CD4+ T cell precursor frequencies (for example, alloreactive responses in transplant settings) or when large numbers of effector CD4+ T cells are present, perhaps during the autoimmune response.

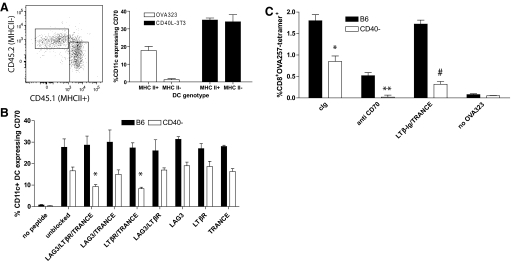

CD40-independent induction of CD70 on DC requires cell–cell contact and is partially mediated by TRANCE and LIGHT/LTαβ

To define the mechanism by which activated CD4+ T cells induce CD70 expression independently from CD40− stimulation, we examined initially whether cognate (TCR-MHC/peptide) interactions were necessary. Thus, cultures containing MHC class II-expressing (CD45.1+) and MHC class II-deficient (CD45.2+) splenocytes, OT-II and OVA323, were initiated. Only those DC that expressed MHC class II exhibited CD70 expression (Fig. 6A). Thus, CD70 induction on DC requires a cognate interaction between the DC and the CD4+ T cell.

Figure 6.

Contribution of LTβR and TRANCE to the expression of CD70 on DC in the absence of CD40. MHC class II+ (CD45.1+) or MHC class II− (CD45.2+) splenocytes were mixed 1:1 in coculture with OT-II T cells and OVA323 peptide or with CD40L-expressing 3T3 cells. Forty-eight hours after culture initiation, splenoctyes were stained for CD70 expression on CD11c+ DC. (A) Dot plots (gated on CD11c+ cells) show MHC class II+ and class II− DC. Bar chart indicates the proportion of MHC class II+ or class II− DC induced to express CD70 by activated CD4+ T cells or CD40L-expressing fibroblasts. (B) CD86 and CD70 expression on B6 or CD40–CD11c+ DC after 48 h coculture with OT-II cells and OVA323 in the presence or absence of blocking antibodies against TRANCE and LAG-3 and the chimeric protein LTβR-Ig. (A) Representative of one of two experiments; (B) representative of three similar experiments. *, P < 0.05, when compared with unblocked, CD40-deficient DC. (C) Immunogenicity of CD40− DC after blockade of LTβR and TRANCE. MHC-tetramer staining of primary CD8+ T cell responses from mice immunized with OVA257-pulsed DC isolated from cultures of B6 or CD40-deficient splenocytes with OT-II, as described in Materials and Methods, and treated with cIg or anti-CD70 prior to immunization. *, P < 0.05, compared with B6 DC; **, P < 0.01, compared with cIg-treated, CD40-deficient DC; #, P < 0.05, compared with cIg-treated, CD40-deficient DC. Experiment was repeated twice.

LTαβ [26], LIGHT [22], TRANCE [27], and LAG-3 [28] have the capability to activate DC in the absence of CD40-CD40L interactions. Therefore, cultures containing wild-type or CD40-deficient splenocytes and OT-II cells were initiated in the presence or absence of a mix of blocking antibodies specific for TRANCE, LAG-3, and chimeric LTβR-Ig. Forty-eight hours after the culture was initiated, wild-type and CD40-deficient DC expressed CD70 (Fig. 6B). Expression of CD70 on CD40-deficient DC was reduced but still significantly detectable in cultures containing the triple block, and expression was maintained in the presence of the triple block on wild-type DC. We found no difference in the number or frequency of CD11c+ cells in the various cultures (data not shown), indicating that blocking these receptors had little effect on DC viability. To define the contribution of the individual costimulation molecules on CD70 induction, cultures of CD40-deficient splenocytes and OT-II cells were established using the blocking antibodies, individually or in combination. None of the blocking conditions individually impacted on CD70 expression. However, a combination of TRANCE-specific antibody and LTβR-Ig recapitulated the reduction in CD70 expression observed with the triple block. To assess the relevance of this alternative pathway, we examined the impact of its blockade on the immunogenicity of the resulting DC. Consistent with the data derived from BMDC cultures (Fig. 2), the magnitude of the primary CD8+ T cell response was reduced significantly when immunizing DC, isolated from cultures of OT-II and B6 splenocytes, were pretreated with anti-CD70. However, LTβR-Ig and anti-TRANCE treatment had limited impact on the immunogenicity of B6 DC. The immunogenicity of CD40-deficient DC was ablated nearly completely after CD70 blockade and reduced significantly if LTβR-Ig and anti-TRANCE were included in the cocultures with OT-II (Fig. 6C). Thus, although CD40-CD40L is the dominant mechanism for inducing CD70 expression on DC, some stimulation generated by TRANCE and LIGHT/LTαβ contributes to CD40-CD40L-independent induction of CD70 expression and consequentially, the immunogenicity of CD40-deficient DC.

An important aspect of the studies presented here is the discovery that although CD40-CD40L interactions are apparently sufficient for CD70 expression and DC immunogenicity, they are not necessary. We have been able to define that the alternative pathway requires antigen-specific engagement of DC and CD4+ T cells, and the reduction in overall levels of CD70 on DC after blocking the CD40L-depedent and -independent pathways suggests that the combination of several less-potent costimulatory molecules may be sufficient to compensate for the lack of CD40L-CD40-mediated costimulation. Thus, CD4+ T cells may use several pathways to induce CD70 expression. In this regard, the failure of LTβR-Ig and anti-TRANCE treatment to impact on the expression of CD70 on B6 DC or the subsequent immunogenicity of these DC is most likely a consequence of the strength of the CD40-mediated stimulation and its independent ability to induce CD70 expression. Alternatively, CD40-mediated stimulation activates additional costimulatory molecule expression, which may be induced inefficiently by LTβR/TRANCE signaling, which contributes to the immunogenicity of the DC. Of note, in our studies and those reported by others [18], blocking CD70 in wild-type mice reduces the primary CD8+ T cell response by ∼50%, indicating that sufficient stimulation can be achieved for a primary CD8+ T cell to be activated in the absence of CD70, albeit at a reduced level.

Regardless of the mechanism by which CD70 is induced on DC by activated CD4+ T cells, blockade of CD70 on DC activated in a CD40-CD40L-permissive or -independent manner resulted in a significant reduction in DC immunogenicity. Thus, the ability of either pathway to generate immunogenic DC is dependent on the expression of CD70. It is important to note that the pathways of activation associated with CD70 stimulation are diverse and complementary; thus, not only will the absence of CD70 on DC directly influence responding CD8+ T cells that engage DC directly, but also, it has been shown that CD70-mediated stimulation of CD4+ T cells has an indirect effect on CD8+ T cell responses [29, 30]. Additionally, studies in our lab suggest that CD70-mediated stimulation of NK cells supports CD8+ T cell responses (T. N. J. Bullock, unpublished data). Thus, the impact of blocking CD70 stimulation on the primary CD8+ T cell response may not be solely a consequence of preventing direct DC stimulation of CD8+ T cells.

The data presented in this study predict that evaluation of vaccines for their ability to induce CD70 on DC should provide a useful biomarker for their efficacy. Likewise, vaccination strategies that incorporate CD27 agonists have the potential to be highly immunogenic, although it should be cautioned that chronic CD70 expression is associated with T cell exhaustion [31].

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute (CA115882), the Cancer Research Institute/Libby Bartnick Memorial Investigator Award, and the University of Virginia Cancer Center support grant P30 CA44579 (all to T. N. J. B.). The authors thank Mike Solga and Joanne Lannigan for assistance with flow cytometry; Allison Robbins, Stefani Mancuso, and Drew Roberts for excellent technical assistance; Drs. Mike Brown, Loren Erikson, and Joe Sung for critical comments about the manuscript; and Drs. Noelle, Fu, and Yagita for the provision of reagents used in these studies.

DISCLOSURE

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: APC=allophycocyanin, B6 mice=C57Bl/6 mice, BMDC=bone marrow-derived dendritic cell, CD40L=CD40 ligand, cIg=control Ig, DC=dendritic cell(s), HBC128=Hepatitis B core 128, LAG-3=lymphocyte-activation gene 3, LIGHT=homologous to lymphotoxins, exhibits inducible expression, and competes with HSV glycoprotein D for herpesvirus entry mediator, LTαβ=lymphotoxin αβ, OVA-adeno=adenovirus expressing OVA, PAM3CSK4=palmitoyl-3-cysteine-serine-lysine-4, PAMP=pathogen-associated molecular pattern, TRANCE=TNF-related activation-induced cytokine

References

- Whitmire J K, Slifka M K, Grewal I S, Flavell R A, Ahmed R. CD40 ligand-deficient mice generate a normal primary cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response but a defective humoral response to a viral infection. J Virol. 1996;70:8375–8381. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8375-8381.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridge J P, Di Rosa F, Matzinger P. A conditioned dendritic cell can be a temporal bridge between a CD4+ T-helper and a T-killer cell. Nature. 1998;393:474–478. doi: 10.1038/30989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S R, Carbone F R, Karamalis F, Miller J F, Heath W R. Induction of a CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte response by cross-priming requires cognate CD4+ T cell help. J Exp Med. 1997;186:65–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenberger S P, Toes R E, van der Voort E I, Offringa R, Melief C J. T-cell help for cytotoxic T lymphocytes is mediated by CD40-CD40L interactions. Nature. 1998;393:480–483. doi: 10.1038/31002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mescher M F, Curtsinger J M, Agarwal P, Casey K A, Gerner M, Hammerbeck C D, Popescu F, Xiao Z. Signals required for programming effector and memory development by CD8+ T cells. Immunol Rev. 2006;211:81–92. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taraban V Y, Rowley T F, Al Shamkhani A. Cutting edge: a critical role for CD70 in CD8 T cell priming by CD40-licensed APCs. J Immunol. 2004;173:6542–6546. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock T N, Yagita H. Induction of CD70 on dendritic cells through CD40 or TLR stimulation contributes to the development of CD8+ T cell responses in the absence of CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:710–717. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez P J, McWilliams J A, Haluszczak C, Yagita H, Kedl R M. Combined TLR/CD40 stimulation mediates potent cellular immunity by regulating dendritic cell expression of CD70 in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;178:1564–1572. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley T F, Al Shamkhani A. Stimulation by soluble CD70 promotes strong primary and secondary CD8+ cytotoxic T cell responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2004;172:6039–6046. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller A M, Schildknecht A, Xiao Y, Van Den B M, Borst J. Expression of costimulatory ligand CD70 on steady-state dendritic cells breaks CD8+ T cell tolerance and permits effective immunity. Immunity. 2008;29:934–946. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesselaar K, Xiao Y, Arens R, van Schijndel G M, Schuurhuis D H, Mebius R E, Borst J, Van Lier R A. Expression of the murine CD27 ligand CD70 in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2003;170:33–40. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares H, Waechter H, Glaichenhaus N, Mougneau E, Yagita H, Mizenina O, Dudziak D, Nussenzweig M C, Steinman R M. A subset of dendritic cells induces CD4+ T cells to produce IFN-γ by an IL-12-independent but CD70-dependent mechanism in vivo. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1095–1106. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taraban V Y, Rowley T F, Tough D F, Al Shamkhani A. Requirement for CD70 in CD4+ Th cell-dependent and innate receptor-mediated CD8+ T cell priming. J Immunol. 2006;177:2969–2975. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamijo S, Nakajima A, Ikeda K, Aoki K, Ohya K, Akiba H, Yagita H, Okumura K. Amelioration of bone loss in collagen-induced arthritis by neutralizing anti-RANKL monoclonal antibody. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;347:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochweller K, Anderton S M. Kinetics of costimulatory molecule expression by T cells and dendritic cells during the induction of tolerance versus immunity in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1086–1096. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima H, Nakano H, Nohara C, Kobata T, Nakajima A, Jenkins N A, Gilbert D J, Copeland N G, Muto T, Yagita H, Okumura K. Characterization of murine CD70 by molecular cloning and mAb. Int Immunol. 1998;10:517–526. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang M L, Lukens J R, Bullock T N. Cognate memory CD4+ T cells generated with dendritic cell priming influence the expansion, trafficking, and differentiation of secondary CD8+ T cells and enhance tumor control. J Immunol. 2007;179:5829–5838. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.5829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schildknecht A, Miescher I, Yagita H, Van Den B M. Priming of CD8+ T cell responses by pathogens typically depends on CD70-mediated interactions with dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:716–728. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett S R, Carbone F R, Karamalis F, Flavell R A, Miller J F, Heath W R. Help for cytotoxic-T-cell responses is mediated by CD40 signaling. Nature. 1998;393:478–480. doi: 10.1038/30996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmire J K, Flavell R A, Grewal I S, Larsen C P, Pearson T C, Ahmed R. CD40-CD40 ligand costimulation is required for generating antiviral CD4 T cell responses but is dispensable for CD8 T cell responses. J Immunol. 1999;163:3194–3201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Yuan L, Zhou X, Sotomayor E, Levitsky H I, Pardoll D M. CD40-independent pathways of T cell help for priming of CD8(+) cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 2000;191:541–550. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers-DeLuca L E, McCarthy D D, Cosovic B, Ward L A, Lo C C, Scheu S, Pfeffer K, Gommerman J L. Expression of lymphotoxin-αβ on antigen-specific T cells is required for DC function. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1071–1081. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J C, Bevan M J. Defective CD8 T cell memory following acute infection without CD4 T cell help. Science. 2003;300:339–342. doi: 10.1126/science.1083317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez M G, Shen L, Rock K L. CD40 on APCs is needed for optimal programming, maintenance, and recall of CD8+ T cell memory even in the absence of CD4+ T cell help. J Immunol. 2008;180:4382–4390. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley M, Martinez J, Huang X, Yang Y. A critical role for direct TLR2-MyD88 signaling in CD8 T-cell clonal expansion and memory formation following vaccinia viral infection. Blood. 2009;113:2256–2264. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-148809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel Y, Truneh A, Sweet R W, Olive D, Costello R T. The TNF superfamily members LIGHT and CD154 (CD40 ligand) costimulate induction of dendritic cell maturation and elicit specific CTL activity. J Immunol. 2001;167:2479–2486. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann M F, Wong B R, Josien R, Steinman R M, Oxenius A, Choi Y. TRANCE, a tumor necrosis factor family member critical for CD40 ligand-independent T helper cell activation. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1025–1031. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.7.1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreae S, Piras F, Burdin N, Triebel F. Maturation and activation of dendritic cells induced by lymphocyte activation gene-3 (CD223) J Immunol. 2002;168:3874–3880. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.3874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolfi D V, Boesteanu A C, Petrovas C, Xia D, Butz E A, Katsikis P D. Late signals from CD27 prevent Fas-dependent apoptosis of primary CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:2912–2921. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Peperzak V, Keller A M, Borst J. CD27 instructs CD4+ T cells to provide help for the memory CD8+ T cell response after protein immunization. J Immunol. 2008;181:1071–1082. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.2.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesselaar K, Arens R, van Schijndel G M, Baars P A, van der Valk M A, Borst J, van Oers M H, Van Lier R A. Lethal T cell immunodeficiency induced by chronic costimulation via CD27-CD70 interactions. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:49–54. doi: 10.1038/ni869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]