Abstract

Priapism is a condition of persistent penile erection in the absence of sexual excitation. Of men with sickle cell disease (SCD), 40% display priapism. The disorder is a dangerous and urgent condition, given its association with penile fibrosis and eventual erectile dysfunction. Current strategies to prevent its progression are poor because of a lack of fundamental understanding of the molecular mechanisms for penile fibrosis in priapism. Here we demonstrate that increased adenosine is a novel causative factor contributing to penile fibrosis in two independent animal models of priapism, adenosine deaminase (ADA)-deficient mice and SCD transgenic mice. An important finding is that chronic reduction of adenosine by ADA enzyme therapy successfully attenuated penile fibrosis in both mouse models, indicating an essential role of increased adenosine in penile fibrosis and a novel therapeutic possibility for this serious complication. Subsequently, we identified that both mice models share a similar fibrotic gene expression profile in penile tissue (including procollagen I, TGF-β1, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 mRNA), suggesting that they share similar signaling pathways for progression to penile fibrosis. Thus, in an effort to decipher specific cell types and underlying mechanism responsible for adenosine-mediated penile fibrosis, we purified corpus cavernosal fibroblast cells (CCFCs), the major cell type involved in this process, from wild-type mice. Quantitative RT-PCR showed that the major receptor expressed in these cells is the adenosine receptor A2BR. Based on this fact, we further purified CCFCs from A2BR-deficient mice and demonstrated that A2BR is essential for excess adenosine-mediated penile fibrosis. Finally, we revealed that TGF-β functions downstream of the A2BR to increase CCFC collagen secretion and proliferation. Overall, our studies identify an essential role of increased adenosine in the pathogenesis of penile fibrosis via A2BR signaling and offer a potential target for prevention and treatment of penile fibrosis, a dangerous complication seen in priapism.—Wen, J., Jiang, X., Dai, Y., Zhang, Y., Tang, Y., Sun, H., Mi, T., Phatarpekar, P. V., Kellems, R. E., Blackburn, M. R., Xia, Y. Increased adenosine contributes to penile fibrosis, a dangerous feature of priapism, via A2B adenosine receptor signaling.

Keywords: adenosine deaminase-deficient mice, sickle cell disease, TGF-β, signaling pathway

Priapism occurs in ∼40% of men with sickle cell disease (SCD) and is prevalent among men with other hematological dyscrasias (1,2,3). This disorder is characterized by a painful prolonged penile erection without sexual desire. Priapism is a dangerous and urgent condition because of its major complication, penile fibrosis. Without interference, it will eventually lead to erectile dysfunction (4). However, the reactive treatments rarely restore normal erectile function and preventive approaches to limit abnormal erection tendencies are lacking because of poor understanding of the pathophysiology of priapism and penile fibrosis. This situation highlights the need for basic research to understand the molecular mechanisms of the disease. Such efforts will lead to better diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of priapism and penile fibrosis.

Recently, we unexpectedly found that mice deficient in the purine catabolic enzyme adenosine deaminase (ADA) with elevated adenosine develop spontaneous prolonged penile erection and penile fibrosis, two major features seen in men with SCD (5, 6). This unexpected observation of spontaneously prolonged penile erection in ADA-deficient mice led us to identify a novel role of excess adenosine signaling in priapism in SCD-transgenic (Tg) mice, a well-accepted animal model of priapism (6,7,8,9,10,11). Our analysis of priapism in ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice revealed a previously unrecognized general pathophysiological role for increased adenosine in increased priapic activity. However, the causative factors and underlying mechanism of penile fibrosis associated with priapism remain unknown.

The pathogenesis of penile fibrosis associated with priapism probably results from a combination of prolonged penile erection, ischemia-mediated inflammatory response, vascular damage, and attempted tissue repair. Multiple factors are released from locally insulted penile tissue and responding cells. Because priapism is commonly associated with hypoxic conditions, one of the best-known signaling molecules to be induced under hypoxic conditions is adenosine (12). Previous studies indicated that adenosine functions as a profibrotic molecule playing a critical role in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis as well as hepatic fibrosis via adenosine receptors (13,14,15). Thus, we speculate that increased adenosine probably contributes to penile fibrosis. In this study, we explore the general pathogenic role of increased adenosine in penile fibrosis in two distinct mouse priapism animal models, ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice. Moreover, we investigate the molecular mechanism of adenosine-mediated penile fibrosis and identify a potential therapeutic possibility.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

ADA-deficient mice were generated and genotyped as described previously (16,17,18). Control mice, designated ADA+, were littermates that were heterozygotes for the null Ada allele. Heterozygous mice do not display a phenotype. All mice were on a mixed 129sV/C57BL/6J background and backcrossed ≥10 generations on the C57BL/6 background. All phenotypic comparisons were performed among littermates. Adenosine receptor A2BR-deficient mice were generated in our laboratory. These mice were backcrossed ≥10 generations onto the C57BL/6 background and were genotyped according to established protocols (19). SCD-Tg mice, expressing exclusively human sickle hemoglobin, were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) (9, 10). For the SCD mice study, wild-type C57BL/6 mice were used as controls. All mice were maintained and housed in accordance with NIH guidelines and with the approval of the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

ADA enzyme therapy

Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-ADA was generated by the covalent modification of purified bovine ADA with activated PEG, as described previously (15, 20, 21). Different doses of PEG-ADA were delivered weekly by intraperitoneal injection to reduce adenosine levels. Specifically, the ADA-deficient mice were maintained on high-dose enzyme therapy at 5 U/wk for ≥8 wk to allow for normal penile development. At 8 wk of age, the dose of PEG-ADA was gradually tapered down over a period of 8 wk to a low dose of 0.625 U/wk (2.5 U for 2 wk, 1.25 U for 2 wk, and 0.625 U for 4 wk). This dosing protocol was designated a “low-dose” (LD) PEG-ADA treatment regimen. Another group of mice was tapered down to a low dose of PEG-ADA for 6 wk and then returned to a high dose of PEG-ADA for 2 wk (2.5 U for 2 wk, 1.25 U for 2 wk, 0.625 U for 2 wk, and 5 U for 2 wk). This dosing protocol was designated a “low dose-high dose” (LD+HD) PEG-ADA treatment regimen. Some ADA-deficient mice were treated with a high dose of PEG-ADA at 5 U/wk since their birth for 16 wk. This dosing protocol was designated a “high-dose” (HD) PEG-ADA treatment regimen. For all experiments, ADA+ mice treated with or without a high dose of PEG-ADA at 5 U/wk were used as the controls.

For SCD-Tg mice, at 8 wk of age the mice were injected with 2.5 U of PEG-ADA weekly for 8 wk. This dosing protocol was designated SCD with PEG-ADA treatment regimen (SCD+PEG-ADA). Other SCD mice were injected with normal saline for 8 wk; this was designated as SCD without PEG-ADA treatment regimen (SCD). Age-matched C57BL6 mice treated with or without PEG-ADA at 2.5 U/wk were used as the controls.

Quantification of penile adenosine levels

Mice were anesthetized, and the penises were rapidly removed and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Adenine nucleosides were extracted from frozen penises using 0.4 N perchloric acid, and adenosine was separated and quantified using reverse-phase HPLC, as described previously (16, 17).

Histological analysis

Mice were anesthetized, and the penises were isolated and pressure-infused with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and fixed overnight at 4°C. Fixed penises were rinsed in PBS, dehydrated through graded ethanol washes, and embedded in paraffin. Sections of 5 μm were collected on slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson’s trichrome, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Shardon Lipshaw, Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

α-Smooth muscle actin (SMA) immunohistochemistry

To evaluate the expression of α-SMA, immunohistochemical analysis was performed on 5-μm sections cut from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded penises. Slides were processed following the instructions for ABC Elite staining reagent (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and incubated with a 1:50 dilution of monoclonal antibody to α-SMA (Vector Laboratories) for 2 h at room temperature. The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Quantitative image analysis

For quantitative image analysis, we used computerized densitometry (ImagePro Plus, version 6.0; Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA) coupled to a microscope equipped with a digital camera (22,23,24,25). The analysis of the collagen to smooth muscle ratio and positive α-SMA area in the sections of corpus cavernosum were processed as described previously (26).

Total RNA isolation and real-time RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). RNase-free DNase (Invitrogen) was used to eliminate genomic DNA contamination. Transcript levels were quantified using real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Cyber green was used for analysis of α2 (I) procollagen, TGF-β1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), and β-actin using the following primers: α2 (I) procollagen, forward 5′-AGACATGCTCAGCTTTGTGGATAC-3′ and reverse 5′-CGTACTGATCCCGATTGCAAAT 3′; TGF-β1, forward 5′-CCCCACTGATACGCCTGAGT-3′ and reverse 5′-GCCCTGTATTCCGTCTCCTT-3′; PAI-1, forward 5′-AGTGATGGAGCCTTGACAG-3′ and reverse 5′-AGGAGGAGTTGCCTTCTCTT-3′; and β-actin, forward 5′-GCTCTGGCTCCTAGCACCAT-3′ and reverse 5′-CCACCGATCCACACAGAGTAC-3′. Adenosine receptor transcripts were analyzed using TaqMan probes, with primer sequences and conditions as described previously (15, 20).

Isolation of primary corpus cavernosal fibroblast cells (CCFCs)

Corpus cavernosa were surgically isolated. The isolated corpus cavernosa were washed in PBS, minced into 2- to 3- mm3 pieces, and suspended in sterile PBS. Dispersed cells were then collected and separated from debris by filtration through sterile gauze. The cells were washed once with PBS, then resuspended in DMEM containing 10% FCS, and cultured in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C as described previously (27, 28). Fibroblasts were stained by fibronectin (a specific fibroblast marker) and CD31 (a specific marker for endothelial cells) using immunofluorescence, as described previously (29). Primary cells were used for experiments at passages 3 and 4.

CCFC culture for mRNA collection and proliferation

Fibroblasts were seeded into flat-bottomed 96-well plates (5000 cells/well) or 10-cm culture dishes (5×105cells/well) in DMEM containing 10% FCS for the proliferation assay and mRNA collection. After 24 h in culture, cells were serum-starved in DMEM without FCS and treated with various drugs. Specifically, 5′-N-ethylcarboxamido-adenosine (NECA; 20 μM), a potent nonmetabolized adenosine analog, MRS1754 (20 μM), a specific A2BR antagonist, and theophylline (20 μM), a general adenosine receptor antagonist, were used. TGF-β1-neutralizing antibody (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) with the final concentration of 0.5 μg/ml was used to inhibit the TGF-β1 activity. After 24 h of treatment, the cell proliferation was measured, following the instructions for the premixed WST-1 cell proliferation kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). Total RNA from CCFCs was isolated as described above.

Statistics

All values are expressed as means ± se. Data were analyzed for statistical significance by Student’s t test and ANOVA using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Elevated adenosine level in penile tissue contributes to penile fibrosis in ADA-deficient mice

To determine the critical role of excess adenosine in penile fibrosis seen in ADA-deficient mice, we regulated adenosine levels with different amounts of PEG-ADA. The PEG modification serves to significantly prolong the serum half-life of the enzyme. The use of PEG-ADA enzyme therapy to regulate adenosine levels in ADA-deficient mice is a powerful experimental strategy to investigate the role of adenosine signaling in the pathophysiology associated with ADA deficiency (30). Specifically, we treated ADA-deficient mice with an HD regimen of PEG-ADA from birth in an effort to maintain normal adenosine levels and allow for normal penile development. At 8 wk of age, half of the group continued to receive HDPEG-ADA therapy (5 U/wk) to prevent the accumulation of adenosine. For the other half, the dose of PEG-ADA was gradually tapered down over a period of 8 wk to an LD of 0.625 U/wk to allow adenosine levels to increase. At 16 wk of age, all of the mice were sacrificed.

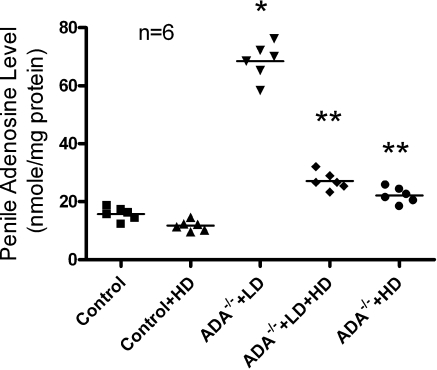

First, we used HPLC to measure adenosine levels in the penile tissues of various groups of mice. We found that the adenosine levels in penises of mice receiving the HD regimen of PEG-ADA were similar to those in penile tissues of the ADA+ controls. However, adenosine levels in the penile tissues of the mice receiving the LD regimen of PEG-ADA were remarkably higher than those of HD-treated mice and the controls (Fig. 1). Thus, PEG-ADA treatment is a useful experimental strategy for controlling the endogenous level of adenosine present in penile tissue.

Figure 1.

Modulation of penile adenosine levels in ADA-deficient mice after different dosages of PEG-ADA treatment. Data are expressed as means ± se (n=6). *P < 0.05 vs. control; **P < 0.05 vs. ADA−/− + LD.

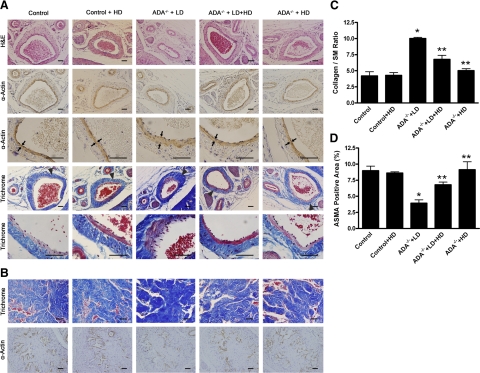

Next, histological studies were conducted to characterize the penile fibrosis in each group of mice. For mice receiving the LD PEG-ADA treatment regimen, H&E staining and anti-α- SMA immunostaining demonstrated extensive endothelial damage, including marked intimal thickening with smooth muscle hypertrophy and endothelial swelling in the deep dorsal vein (Fig. 2A). Masson’s trichrome staining showed significant fibrosis with extension into the intima in the deep dorsal vein (Fig. 2A). Substantial fibrosis with collagen deposition was also observed in the corpus cavernosum, accompanied by loss of vascular smooth muscle cells (Fig. 2B). Quantitative image analysis showed a significantly increased ratio of collagen to smooth muscle and reduced positive α-SMA area in the corpus cavernosum (Fig. 2C, D), indicating smooth muscle damage and increased penile fibrosis. However, the HD-treated ADA-deficient mice did not display obvious vascular damage or penile fibrosis as seen in the LD-treated ADA-deficient mice. Taken together, these results indicate that increased adenosine contributes to penile fibrosis and that chronic reduction of adenosine levels by PEG-ADA enzyme therapy prevents development of penile fibrosis in ADA-deficient mice.

Figure 2.

Elevated adenosine level in penile tissue contributes to penile fibrosis in ADA-deficient mice. A) For LD PEG-ADA-treated ADA-deficient mice, H&E staining and anti-α-SMA immunostaining demonstrated extensive endothelial damage, including marked intimal thickening with smooth muscle hypertrophy and endothelial swelling in the deep dorsal vein. Masson’s trichrome staining showed significant fibrosis with extension into the intima that was also seen in the deep dorsal vein. Vascular damage and penile fibrosis were prevented in the HD-treated mice since their birth (HD group) and attenuated with HD PEG-ADA treatment after establishment of penile fibrosis in LD-treated mice (LD+HD group), respectively. Arrows indicate hypertrophy of smooth muscle of the deep dorsal vein in LD-treated mice. Triangles indicate vascular damage featured with intimal thickening and fibrosis in LD-treated mice. B) Masson’s trichrome staining and anti-α-SMA immunostaining showed substantial fibrosis in the corpus cavernosum accompanied by loss of vascular smooth muscle cells in ADA-deficient mice receiving the LD treatment regimen. These features were either prevented or attenuated in mice receiving the HD treatment since birth or the LD + HD PEG-ADA treatment regimen, respectively. C, D) Quantitative image analysis showed that LD PEG-ADA-treated mice exhibited an increased collagen to smooth muscle (SM) ratio (C) and decreased positive α-actin smooth muscle area (ASMA) in corpus cavernosum (D). Data are expressed as means ± se (n=5). *P < 0.05 vs. control; **P < 0.05 vs. ADA−/− + LD. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Effects of PEG-ADA enzyme therapy on established penile fibrosis in ADA-deficient mice

The previous section provided direct evidence that increased adenosine contributed to penile fibrosis in ADA-deficient mice and that HD PEG-ADA enzyme therapy from birth prevented penile fibrosis. However, whether PEG-ADA has a therapeutic effect on established penile fibrosis is unknown. To address this possibility, mice with established penile fibrosis as a result of placement on the LD regimen of PEG-ADA enzyme therapy as described above were switched to the HD regimen of PEG-ADA enzyme therapy (5 U/wk) for 2 wk (LD→HD). Adenosine levels in penile tissue were significantly reduced after 2 wk of HD PEG-ADA therapy compared with those of mice that continued to receive the LD treatment regimen (Fig. 1). Intriguingly, we found that increased penile fibrosis seen in the LD regimen was significantly attenuated by 2 wk of HD PEG-ADA therapy (Fig. 2, ADA−/−+LD→ HD). Thus, these results indicate that PEG-ADA enzyme therapy is capable of reversing established penile fibrosis in ADA-deficient mice. Taken together, our results using ADA-deficient mice coupled with PEG-ADA enzyme therapy have demonstrated that increased adenosine contributes to penile fibrosis and that PEG-ADA is a safe and effective drug to prevent and treat penile fibrosis seen in ADA-deficient mice.

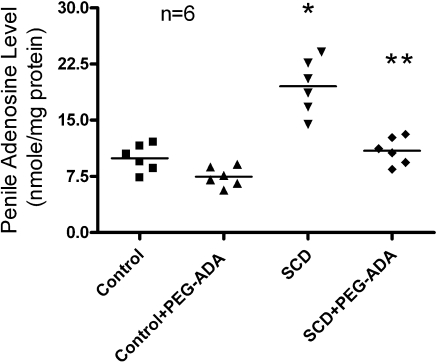

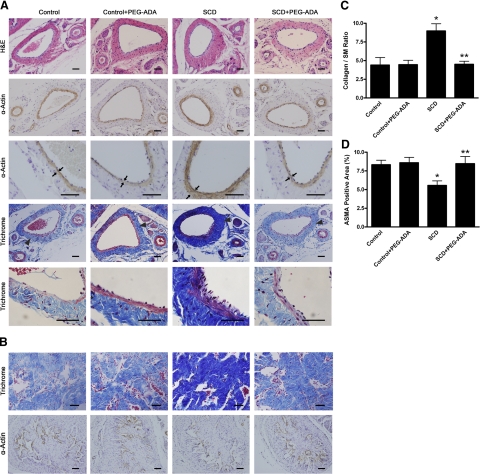

Contributory role of elevated adenosine and general therapeutic possibility of PEG-ADA enzyme therapy in penile fibrosis associated with SCD-Tg mice

To determine the importance of the contributory role of adenosine signaling in penile fibrosis and explore the general utility of PEG-ADA on the treatment of penile fibrosis, we extended our studies from ADA-deficient mice to further evaluate the pathogenic role of adenosine and the therapeutic potential of PEG-ADA in SCD-Tg mice, a well-accepted animal model of priapism (6,7,8,9,10,11). Specifically, at the age of 8 wk, SCD-Tg mice were treated with PEG-ADA (2.5 U/wk) to reduce the elevated levels of adenosine in penis. Noninjected mice served as controls. After 8 wk of PEG-ADA enzyme therapy, the adenosine concentration in penises of SCD-Tg mice were significantly reduced (Fig. 3). Similar to the ADA-deficient mice described above, SCD-Tg mice that did not receive PEG-ADA enzyme therapy had elevated adenosine levels in penile tissues and showed extensive endothelial damage, including marked intimal thickening with smooth muscle hypertrophy and endothelial swelling in the deep dorsal vein (Fig. 4A). Masson’s trichrome staining showed significant fibrosis with extension into the intima of the deep dorsal vein (Fig. 4A). Substantial fibrosis with collagen deposition was also observed in the corpus cavernosum, accompanied by loss of vascular smooth muscle cells (Fig. 4B). Quantitative image analysis showed a significantly increased ratio of collagen to smooth muscle and a reduced positive α-SMA area in the corpus cavernosum (Fig. 4C, D), indicating smooth muscle damage and increased penile fibrosis. Notably, after 8 wk of PEG-ADA therapy, the penile fibrosis was almost completely eliminated from the SCD-Tg mice (Fig. 4, SCD+PEG-ADA). Overall, these results indicate that increased adenosine contributes to the penile fibrosis in SCD-Tg mice and that PEG-ADA enzyme therapy is capable of reversing penile fibrosis in SCD-Tg mice.

Figure 3.

Elevated adenosine levels in penile tissues of SCD-Tg mice were reduced by PEG-ADA enzyme therapy. Data are expressed as means ± se (n=6). *P < 0.05 vs. control; **P < 0.05 vs. SCD.

Figure 4.

SCD-Tg mice display penile fibrosis due to elevations of adenosine levels in penile tissues. A) Very similar to ADA-deficient mice, SCD-Tg mice without PEG-ADA treatment displayed vascular damage and fibrosis in the deep dorsal vein. Lowering penile adenosine levels after established penile fibrosis by PEG-ADA enzyme therapy resulted in a significant resolution of vascular damage and fibrosis. Arrows indicate hypertrophy of smooth muscle in the deep dorsal vein of SCD mice. Triangles indicate penile vascular damage featured with intimal thickening and fibrosis in SCD mice. B) SCD-Tg mice exhibited penile fibrosis and smooth muscle damage in the corpus cavernosum. Lowering penile adenosine levels after established priapism and fibrosis by PEG-ADA enzyme therapy attenuates these abnormalities. C, D) Quantitative image analyses showed that SCD-Tg mice exhibited the increased collagen to smooth muscle (SM) ratio (C) and decreased positive α-actin smooth muscle area (ASMA) in the corpus cavernosum (D). Data are expressed as means ± se (n=6). *P < 0.05 vs. control; **P < 0.05 vs. SCD. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Elevated adenosine contributes to increased expression of fibrotic marker genes in penile tissues of ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice

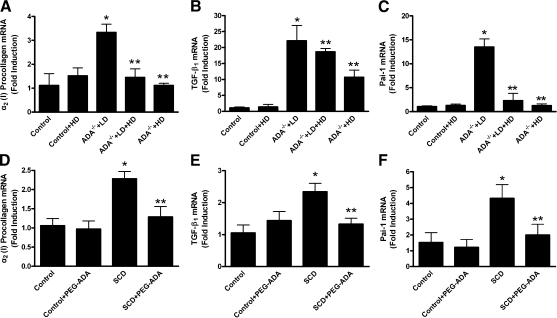

In the previous section, we showed that increased adenosine contributed to penile fibrosis in both ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice. To determine the common intermediates for this process, we examined the expression of fibrotic mediators in the penile tissue of both ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice. We found that the expression of procollagen I, TGF-β1, and PAI-1 mRNA was significantly increased in the penises of ADA-deficient mice maintained on the LD regimen of PEG-ADA and SCD-Tg mice (Fig. 5). Thus, ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice share a similar fibrotic gene expression profile in penile tissue, suggesting that they share similar signaling pathways for progression to penile fibrosis.

Figure 5.

Elevated adenosine contributes to increased expression of fibrotic marker genes in the penile tissues of LD-treated ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice. A–C) Expression of the fibrotic marker genes in penile tissues of ADA-deficient mice receiving the LD regimen significantly increased. HD and LD+HD PEG-ADA treatment regimens for ADA-deficient mice prevented and attenuated the increased expression of fibrotic mediators. Collagen I mRNA (A), TGF-β1 mRNA (B), and PAI-1 mRNA (C) in control and PEG-ADA-treated mice. Data are expressed as means ± se (n=4–5). *P < 0.05 vs. control; **P < 0.05 vs. ADA−/− + LD. D–F) SCD-Tg mice exhibited increased expression of fibrotic mediators in penile tissue. PEG-ADA inhibited the increased expression in SCD-Tg mice. Collagen I mRNA (D) TGF-β1 mRNA (E), and PAI-1 mRNA (F). Data are expressed as means ± se (n=5–6). *P < 0.05 vs. control; **P < 0.05 vs. SCD.

Adenosine is a well-known signaling molecule that is induced under hypoxic conditions (12). Because priapism is commonly associated with hypoxic conditions and excess adenosine is identified as a causal factor for priapism in both ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice (5, 6), it is possible that increased adenosine also contributes to increased fibrotic gene profiles in both ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice. To test this possibility, we determined the effects of PEG-ADA enzyme therapy on the expression of these genes in penile tissues of these mice. For ADA-deficient mice, the increased expression of fibrotic mediators resulting from the LD regimen was significantly inhibited by 2 wk of HD PEG-ADA therapy (Fig. 5A–C, ADA−/−+LD→HD). Similarly, the increased expression of fibrotic mediators was prevented by maintenance of ADA-deficient mice on the HD regimen from birth (Fig. 5A–C, ADA−/−+HD). For SCD-Tg mice, the increase in fibrotic mediators in penile tissue was also significantly blocked by 8 wk of HD PEG-ADA therapy (Fig. 5D–F, SCD+PEG-ADA). These results demonstrate that elevated adenosine contributes to increased expression of fibrotic marker genes and plays an important role in penile fibrosis. The ability to lower adenosine levels by PEG-ADA enzyme therapy has important therapeutic implications for the treatment and prevention of penile fibrosis.

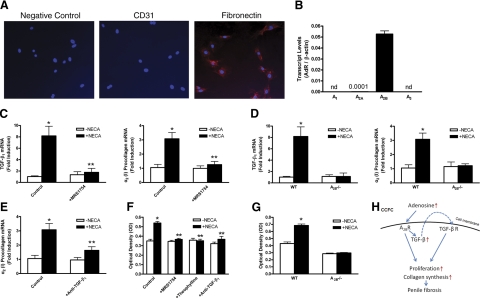

Adenosine A2B receptor is essential for increased fibrotic gene expression

The results presented above indicate that excess adenosine contributes to penile fibrosis with similar fibrotic gene expression in both ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice, suggesting common signaling pathways and cell types in this process. However, it is difficult to determine cell types and molecular mechanisms involved in adenosine-mediated penile fibrosis in intact animals in vivo. In an effort to decipher specific cell types involved in penile fibrosis, we isolated and cultured primary CCFCs, a major cell type involved in fibrosis. These cells were stained by fibronectin, a specific fibroblast marker, but not CD31, an endothelial cell marker (Fig. 6A). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of adenosine receptor transcripts in CCFCs indicated that the A2B adenosine receptor transcript was by far the most abundant in the wild-type CCFCs (Fig. 6B). This finding suggests that this receptor is likely to mediate adenosine-induced fibrotic gene expression in CCFCs. To test this possibility, we treated CCFCs with or without NECA, a potent nonmetabolized adenosine analog (20 μM), for 24 h. Quantitative RT-PCR revealed that NECA increased TGF-β1 mRNA expression and procollagen I mRNA levels by 8- and 3-fold, respectively (Fig. 6C). This induction was completely abolished by the A2BR specific antagonist, MRS1754 (Fig. 6C). To confirm this pharmacological finding we isolated and cultured primary CCFCs from A2BR-deficient mice. Consistent with the pharmacological findings, we found that genetic deletion of A2BR abolished NECA-induced procollagen I and TGF-β1 mRNA production in CCFCs (Fig. 6D). Taken together, the pharmacological and genetic studies demonstrate that the A2BR is essential for adenosine-induced fibrotic gene expression in CCFCs.

Figure 6.

TGF-β is a common intracellular signaling molecule downstream of the A2B adenosine receptor responsible for excess adenosine-mediated penile fibrosis by increased procollagen production and proliferation of fibroblasts. A) Primary isolated CCFCs were stained by fibronectin, a fibroblast-specific marker, not by CD 31, an endothelial cell-specific marker. B) A2BR is major receptor expressed in CCFCs. Quantitative RT-PCR was used to determine the gene expression of adenosine receptors in CCFCs. Data are expressed as means ± se (n=4). C) NECA increased the expression of TGF-β1 mRNA and procollagen I mRNA levels in CCFCs, which was completely abolished by the A2BR specific antagonist, MRS1754 (n=4–6). *P < 0.05 vs. no treatment; **P < 0.05 vs. NECA treatment. D) Genetic deletion of A2BR abolished the NECA-induced procollagen I and TGF-β1 mRNA production (n=5). *P < 0.05 vs. untreated wild-type CCFCs. E) NECA-induced procollagen I mRNA expression was abolished by TGF-β1-neutralizing antibody (n=4–6). *P < 0.05 vs. no treatment; **P < 0.05 vs. NECA treatment. F) Adenosine-induced TGF-β production leads to increased fibroblast proliferation via A2BR activation. NECA, a nonmetabolized adenosine receptor agonist (20 μM), significantly increased CCFC proliferation. MRS1754, a A2BR specific antagonist (20 μM), theophylline, a general adenosine receptor antagonist (20 μM), and TGF-β1-neutralizing antibody (0.5 μg/ml) markedly inhibited NECA-induced proliferation. Data are expressed as means ± se (n=8). *P < 0.05 vs. no treatment; **P < 0.05 vs. NECA treatment. G) Genetic deletion of A2BR completely abolished NECA-induced fibroblast proliferation (n=8). *P < 0.05 vs. untreated wild-type CCFCs. H) Signaling pathway for excess adenosine-mediated penile fibrosis. Excess adenosine increases the expression of TGF-β1 via A2B adenosine receptor in fibroblasts. Increased TGF-β1 functioning as an autocrine fashion leads to penile fibrosis by increased collagen synthesis and proliferation in fibroblasts in the corpus cavernosum.

TGF-β1 is a common signaling molecule responsible for adenosine-induced procollagen gene expression

The results presented above indicate that penile fibrosis in both ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice is associated with increased procollagen and TGF-β1 production via excess A2BR signaling. Realizing that TGF-β1 is a profibrotic mediator whose expression increased in both ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice, we hypothesized that TGF-β1 is responsible for adenosine-induced procollagen expression in penile tissues of both ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice. To test this hypothesis, we treated the CCFCs with NECA (20 μM) in the presence or absence of TGF-β1-neutralizing antibody for 24 h. We found that the NECA-induced procollagen I mRNA expression was abolished by TGF-β1-neutralizing antibody (Fig. 6E). These findings indicate that adenosine-induced TGF-β1 production functions in an autocrine manner to induce matrix protein production associated with penile fibrosis.

Adenosine-induced TGF-β production leads to increased fibroblast proliferation via A2BR activation

TGF-β is a potent profibrotic factor and known to induce fibroblast proliferation (31,32,33). We found that excess adenosine induced TGF-β mRNA expression in penile tissues of both ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice (Fig. 5). Subsequently, we found that adenosine also induced TGF-β mRNA expression in primary CCFCs via A2BR activation (Fig. 6C). Therefore, it is possible that TGF-β functions downstream of A2BR activation to increase fibroblast proliferation. To test this hypothesis, CCFCs were exposed to NECA (20 μM), in the presence or absence of an A2BR specific antagonist, MRS1754 (20 μM). The results showed that NECA significantly increased CCFC proliferation up to 60% and that MRS1754 markedly attenuated this effect (Fig. 6F). Furthermore, the genetic deletion of the A2BR completely abolished NECA-induced fibroblast proliferation (Fig. 6G). Thus, both pharmacological and genetic evidence indicates that adenosine is capable of inducing penile fibrosis by increasing fibroblast proliferation via A2BR activation. Finally, using TGF-β1-neutralizing antibody, we found that NECA-induced fibroblast proliferation was significantly inhibited, indicating that TGF-β is an intercellular signaling molecule induced by adenosine via A2BR activation and responsible for increased fibroblast proliferation in an autocrine manner (Fig. 6F). Taking our results together, we have determined that TGF-β is a critical profibrotic mediator in penile tissues and is responsible for increased fibroblast proliferation and increased procollagen expression via A2BR signaling.

DISCUSSION

Here we have shown that increased adenosine contributes to penile fibrosis and that chronic reduction of adenosine levels by PEG-ADA enzyme therapy attenuates this process in two independent animal models of priapism, ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice. Mechanistically, using both pharmacological and genetic tools we have shown that TGF-β functions downstream of the A2BR responsible for excess adenosine-mediated penile fibrosis seen in both lines of mice. Overall, our studies reveal a novel role of excess adenosine in pathogenesis of penile fibrosis and a previously unrecognized novel application of PEG-ADA in prevention and treatment of penile fibrosis.

Fibrosis is a common complication of priapism (34). There are relatively few animal models available to study the causative factors and specific signaling pathways involved in penile fibrosis. A major observation from our earlier studies was that elevated adenosine in ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice not only induced priapic activity but also was associated with vascular damage and penile fibrosis, serious complications of priapism seen in humans (5, 6). The pathophysiological role of adenosine in penile fibrosis seen in priapism was not identified until we showed here that decreased adenosine levels by PEG-ADA enzyme therapy attenuate penile fibrosis seen in two independent animal models of priapism, ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice. Taken together, these results indicate that increased adenosine contributes to penile fibrosis. The essential role of adenosine in penile fibrosis raises a novel therapeutic possibility for this dangerous disorder. The use of PEG-ADA enzyme therapy from birth for ADA-deficient mice prevented penile fibrosis. Notably, treatment of ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice with established penile fibrosis with PEG-ADA also reversed the penile fibrosis associated with the increased expression of profibrotic genes. Therefore, these findings revealed that increased adenosine contributes to penile fibrosis and PEG-ADA represents a novel therapeutic approach to prevent penile fibrosis and attenuate the established vascular damage and penile fibrosis in general.

Notably, the inhibition of vascular damage and reduction in fibrotic gene expression in penile tissue of SCD-Tg mice after PEG-ADA treatment (SCD+PEG-ADA) was much more extensive than that seen in ADA-deficient mice receiving the LD → HD regimen of PEG-ADA treatment (Figs. 2, 4, and 5). Possible reasons for this difference are as follows. 1) We started to treat SCD-Tg mice with established priapism at a much earlier and younger age, approximately 8 wk old. In contrast, we started to treat ADA-deficient mice with established priapism at 14 wk of age. 2) We treated SCD-Tg mice for a much longer period, approximately 8 wk. In contrast, we only treated ADA-deficient mice with HD PEG-ADA for 2 wk. 3) Quantitative RT-PCR indicated that the fibrotic marker gene expression and adenosine levels are significantly higher in ADA-deficient mice with LD PEG-ADA treatment (ADA−/−+LD) than those seen in SCD-Tg mice without PEG-ADA treatment (SCD group), indicating a much more severe penile fibrosis in ADA-deficient mice than in SCD-Tg mice before the start of HD PEG-ADA treatment. 4) ADA-deficient mice present much higher levels of adenosine in penile tissues than those seen in SCD-Tg mice. Taken together, these findings point out that the effect of PEG-ADA enzyme therapy on inhibition of the progression of penile vascular damage and fibrosis is dependent on adenosine levels, age and severity of penile fibrosis, and length of the treatment. Overall, these results indicate that increased adenosine contributes to vascular damage and penile fibrosis and that PEG-ADA enzyme therapy is capable of attenuating this process.

The progressive nature of penile fibrosis seen in both ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice suggests that adenosine may activate common pathways that maintain or promote the progression from priapism to penile fibrosis. Both of these animal models are useful for examining common mechanisms and potential therapeutic possibilities by targeting adenosine-mediated fibrosis and by investigating the cellular signaling pathways involved in the progression, maintenance, and resolution of penile fibrosis. We have used both in vivo and in vitro approaches to characterize adenosine levels, adenosine receptors, and signaling pathways involved in penile fibrosis. Using PEG-ADA enzyme therapy we have shown that increased adenosine is an important contributing factor for penile fibrosis in ADA-deficient and SCD-Tg mice. Moreover, we found that these mice share similar expression profiles of mediators of penile fibrosis, such as TGF-β, PAI-1, and procollagen, suggesting that penile fibrosis in both lines of mice shares common mechanistic pathways that may be directly or indirectly influenced by excess adenosine signaling. Using pharmacological and genetic approaches we determined that increased adenosine functions through the A2BR to stimulate fibroblast proliferation and procollagen expression. Finally, we have demonstrated that TGF-β, a potent profibrotic factor, is induced by adenosine in CCFCs via A2BR activation. Increased TGF-β secreted from CCFCs functions in an autocrine fashion to induce fibroblast proliferation and increased production of procollagen, a major fibrotic protein. Taken together, our studies show that adenosine-induced A2BR activation resulted in increased production of TGF-β by CCFCs. The resulting increase in TGF-β production contributes to penile fibrosis by stimulating fibroblast proliferation and increased procollagen synthesis (Fig. 6H).

Adenosine is a purine-signaling nucleoside that is highly induced under hypoxic conditions (12). Priapism is associated with severe ischemia (35). Once produced, adenosine can engage specific G protein-coupled receptors on the surface of cells. Four adenosine receptors have been identified (A1R, A2AR, A2BR, and A3R) (36,37,38,39). Among the four adenosine receptors, the A2BR has the lowest affinity for adenosine (39). It is likely that A2B receptors are only engaged under pathological conditions, such as hypoxia, that contribute to elevated adenosine. This view is consistent with our early studies in ADA-deficient mice and SCD-Tg mice, in which we have shown that pathological conditions for each mouse include elevated levels of penile adenosine. Thus, the concentrations of adenosine achieved in the penises of these mutant mice are sufficient to activate the A2BR and lead to priapism (5, 6). Here we have shown that A2BR is the major adenosine receptor expressed in purified CCFCs and is responsible for adenosine-mediated penile fibrosis. These findings immediately imply that antagonism of the A2B adenosine receptor is another promising treatment option for priapism and penile fibrosis.

In this study, we demonstrated that increased adenosine is a novel molecule functioning downstream of the A2BR responsible for penile fibrosis in two animal models of priapism. Notably, the discovery of excess adenosine as the causative factor for both prolonged penile erection and penile fibrosis in mice opens up the possibility of treating and even preventing this painful and dangerous disorder causing penile fibrosis with PEG-ADA enzyme therapy to reduce adenosine or specific antagonists to block A2BR signaling.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. National Institute of Health grants DK077748 (to Y.X.), DK083559 (to Y.X), and HL070952 (to M.R.B.) and by China Scholarship Council 2008637068 (to J. W.).

References

- Bruno D, Wigfall D R, Zimmerman S A, Rosoff P M, Wiener J S. Genitourinary complications of sickle cell disease. J Urol. 2001;166:803–811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diggs L W, Ching R E. Pathology of sickle cell anemia. South Med J. 1934;27:839–845. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Horst C, Stuebinger H, Seif C, Melchior D, Martinez-Portillo F J, Juenemann K P. Priapism—etiology, pathophysiology and management. Int Braz J Urol. 2003;29:391–400. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382003000500002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett A L. Erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2006;175:S25–31. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00309-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y, Zhang Y, Phatarpekar P, Mi T, Zhang H, Blackburn M R, Xia Y. Adenosine signaling, priapism and novel therapies. J Sex Med. 2009;6:292–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi T, Abbasi S, Zhang H, Uray K, Chunn J L, Xia L W, Molina J G, Weisbrodt N W, Kellems R E, Blackburn M R, Xia Y. Excess adenosine in murine penile erectile tissues contributes to priapism via A2B adenosine receptor signaling. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1491–1501. doi: 10.1172/JCI33467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bivalacqua T J, Musicki B, Hsu L L, Gladwin M T, Burnett A L, Champion H C. Establishment of a transgenic sickle-cell mouse model to study the pathophysiology of priapism. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2494–2504. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01359.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claudino M A, Franco-Penteado C F, Corat M A, Gimenes A P, Passos L A, Antunes E, Costa F F. Increased cavernosal relaxations in sickle cell mice priapism are associated with alterations in the NO-cGMP signaling pathway. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2187–2196. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paszty C. Transgenic and gene knock-out mouse models of sickle cell anemia and the thalassemias. Curr Opin Hematol. 1997;4:88–93. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199704020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paszty C, Brion C M, Manci E, Witkowska H E, Stevens M E, Mohandas N, Rubin E M. Transgenic knockout mice with exclusively human sickle hemoglobin and sickle cell disease. Science. 1997;278:876–878. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan T M, Ciavatta D J, Townes T M. Knockout-transgenic mouse model of sickle cell disease. Science. 1997;278:873–876. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm B B. Adenosine, an endogenous distress signal, modulates tissue damage and repair. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1315–1323. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan E S, Montesinos M C, Fernandez P, Desai A, Delano D L, Yee H, Reiss A B, Pillinger M H, Chen J F, Schwarzschild M A, Friedman S L, Cronstein B N. Adenosine A2A receptors play a role in the pathogenesis of hepatic cirrhosis. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:1144–1155. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che J, Chan E S, Cronstein B N. Adenosine A2A receptor occupancy stimulates collagen expression by hepatic stellate cells via pathways involving protein kinase A, Src, and extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 signaling cascade or p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:1626–1636. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.038760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chunn J L, Molina J G, Mi T, Xia Y, Kellems R E, Blackburn M R. Adenosine-dependent pulmonary fibrosis in adenosine deaminase-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2005;175:1937–1946. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn M R, Datta S K, Kellems R E. Adenosine deaminase-deficient mice generated using a two-stage genetic engineering strategy exhibit a combined immunodeficiency. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5093–5100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.5093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn M R, Datta S K, Wakamiya M, Vartabedian B S, Kellems R E. Metabolic and immunologic consequences of limited adenosine deaminase expression in mice. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15203–15210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.15203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn M R, Kellems R E. Adenosine deaminase deficiency: metabolic basis of immune deficiency and pulmonary inflammation. Adv Immunol. 2005;86:1–41. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(04)86001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J F, Huang Z, Ma J, Zhu J, Moratalla R, Standaert D, Moskowitz M A, Fink J S, Schwarzschild M A. A2A adenosine receptor deficiency attenuates brain injury induced by transient focal ischemia in mice. J Neurosci. 1999;19:9192–9200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09192.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chunn J L, Mohsenin A, Young H W, Lee C G, Elias J A, Kellems R E, Blackburn M R. Partially adenosine deaminase-deficient mice develop pulmonary fibrosis in association with adenosine elevations. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L579–L587. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00258.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chunn J L, Young H W, Banerjee S K, Colasurdo G N, Blackburn M R. Adenosine-dependent airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in partially adenosine deaminase-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2001;167:4676–4685. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila H H, Magee T R, Vernet D, Rajfer J, Gonzalez-Cadavid N F. Gene transfer of inducible nitric oxide synthase complementary DNA regresses the fibrotic plaque in an animal model of Peyronie’s disease. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:1568–1577. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.030833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrini M G, Davila H H, Kovanecz I, Sanchez S P, Gonzalez-Cadavid N F, Rajfer J. Vardenafil prevents fibrosis and loss of corporal smooth muscle that occurs after bilateral cavernosal nerve resection in the rat. Urology. 2006;68:429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovanecz I, Rambhatla A, Ferrini M, Vernet D, Sanchez S, Rajfer J, Gonzalez-Cadavid N. Long-term continuous sildenafil treatment ameliorates corporal veno-occlusive dysfunction (CVOD) induced by cavernosal nerve resection in rats. Int J Impot Res. 2008;20:202–212. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernet D, Ferrini M G, Valente E G, Magee T R, Bou-Gharios G, Rajfer J, Gonzalez-Cadavid N F. Effect of nitric oxide on the differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts in the Peyronie’s fibrotic plaque and in its rat model. Nitric Oxide. 2002;7:262–276. doi: 10.1016/s1089-8603(02)00124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovanecz I, Rambhatla A, Ferrini M G, Vernet D, Sanchez S, Rajfer J, Gonzalez-Cadavid N. Chronic daily tadalafil prevents the corporal fibrosis and veno-occlusive dysfunction that occurs after cavernosal nerve resection. BJU Int. 2008;101:203–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickelberg O, Pansky A, Koehler E, Bihl M, Tamm M, Hildebrand P, Perruchoud A P, Kashgarian M, Roth M. Molecular mechanisms of TGF-β antagonism by interferon γ and cyclosporine A in lung fibroblasts. FASEB J. 2001;15:797–806. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0233com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konigshoff M, Wilhelm A, Jahn A, Sedding D, Amarie O V, Eul B, Seeger W, Fink L, Gunther A, Eickelberg O, Rose F. The angiotensin II receptor 2 is expressed and mediates angiotensin II signaling in lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;37:640–650. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0379TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H, Belardinelli L, Maa T, Zeng D. Synergy between A2B adenosine receptors and hypoxia in activating human lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;32:2–8. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2004-0103OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn M R, Aldrich M, Volmer J B, Chen W, Zhong H, Kelly S, Hershfield M S, Datta S K, Kellems R E. The use of enzyme therapy to regulate the metabolic and phenotypic consequences of adenosine deaminase deficiency in mice: differential impact on pulmonary and immunologic abnormalities. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32114–32121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005153200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Andrade C R, Cotrin P, Graner E, Almeida O P, Sauk J J, Coletta R D. Transforming growth factor-β1 autocrine stimulation regulates fibroblast proliferation in hereditary gingival fibromatosis. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1726–1733. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.12.1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez A, Ramadan B, Ritzenthaler J D, Rivera H N, Jones D P, Roman J. Extracellular cysteine/cystine redox potential controls lung fibroblast proliferation and matrix expression through upregulation of transforming growth factor-beta. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L972–L981. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00010.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutz F, Zeisberg M, Renziehausen A, Raschke B, Becker V, van Kooten C, Muller G. TGF-β1 induces proliferation in human renal fibroblasts via induction of basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2) Kidney Int. 2001;59:579–592. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.059002579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett A L. Priapism pathophysiology: clues to prevention. Int J Impot Res. 2003;15:S80–S85. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett A L. Pathophysiology of priapism: dysregulatory erection physiology thesis. J Urol. 2003;170:26–34. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000046303.22757.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekharan B P, Kolachala V L, Dalmasso G, Merlin D, Ravid K, Sitaraman S V, Srinivasan S. Adenosine 2B receptors (A2BAR) on enteric neurons regulate murine distal colonic motility. FASEB J. 2009;23:2727–2734. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-129544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronstein B N. Adenosine receptors and wound healing. Sci World J. 2004;4:1–8. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2004.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm B B, IJzerman A P, Jacobson K A, Klotz K N, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:527–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershfield M S. New insights into adenosine-receptor-mediated immunosuppression and the role of adenosine in causing the immunodeficiency associated with adenosine deaminase deficiency. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:25–30. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth C, Hershfield M, Notarangelo L, Buckley R, Hoenig M, Mahlaoui N, Cavazzana-Calvo M, Aiuti A, Gaspar H B. Management options for adenosine deaminase deficiency; proceedings of the EBMT satellite workshop (Hamburg, March 2006) Clin Immunol. 2007;123:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachid-Filho D, Cavalcanti A G, Favorito L A, Costa W S, Sampaio F J. Treatment of recurrent priapism in sickle cell anemia with finasteride: a new approach. [E-pub ahead of print] Urology. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.04.071. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2009.04.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]