Abstract

Objective

To find out whether taking images of the male and female genitals during coitus is feasible and to find out whether former and current ideas about the anatomy during sexual intercourse and during female sexual arousal are based on assumptions or on facts.

Design

Observational study.

Setting

University hospital in the Netherlands.

Methods

Magnetic resonance imaging was used to study the female sexual response and the male and female genitals during coitus. Thirteen experiments were performed with eight couples and three single women.

Results

The images obtained showed that during intercourse in the “missionary position” the penis has the shape of a boomerang and 1/3 of its length consists of the root of the penis. During female sexual arousal without intercourse the uterus was raised and the anterior vaginal wall lengthened. The size of the uterus did not increase during sexual arousal.

Conclusion

Taking magnetic resonance images of the male and female genitals during coitus is feasible and contributes to understanding of anatomy.

Introduction

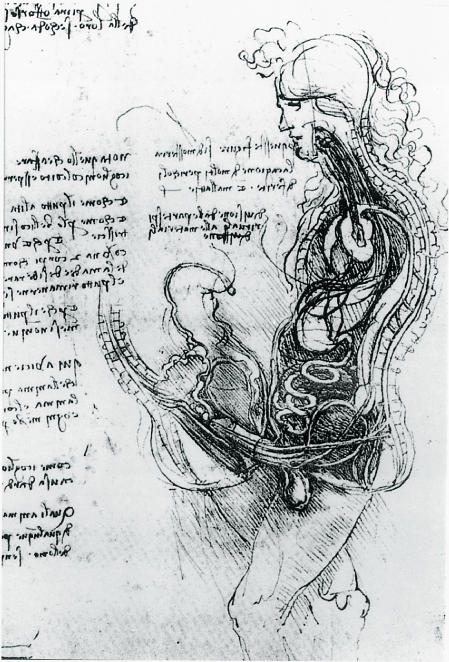

“I expose to men the origin of their first, and perhaps second, reason for existing.”1 Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) wrote these words above his drawing “The Copulation” in about 1493 (fig 1).2 The Renaissance sketch shows a transparent view of the anatomy of sexual intercourse as envisaged by the anatomists of his time. The semen was supposed to come down from the brain through a channel which can be seen in the spine of the man. In the woman the right lactiferous duct is depicted as originating in the right female breast and ending in the genital area. Even a genius like Leonardo da Vinci distorted men's and women's bodies—as seen now—to fit the ideology of his time and to the notions of his colleagues, who he paid tribute to.

Figure 1.

“The Copulation” as imagined and drawn by Leonardo da Vinci.2 With permission from the Royal Collection. Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II is gratefully acknowledged

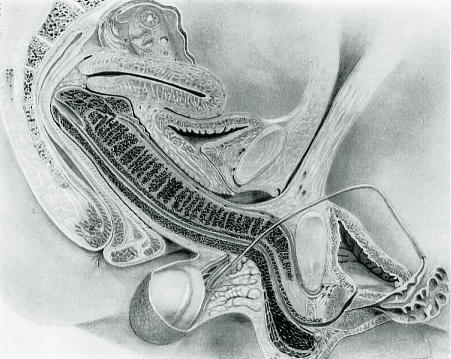

The first careful study—since the sketch by Leonardo da Vinci—of the interaction of male and female human genitals during coitus was published by Dickinson in 1933 (fig 2).3 A glass test tube as big as a penis in erection inserted into the vagina of female subjects who were sexually aroused by clitoral stimulation (occasionally with a vibrator) guided him in constructing his pictorial supposition.

Figure 2.

Midsagittal image of the anatomy of sexual intercourse envisaged by R L Dickinson and drawn by R S Kendall3

In the 1960s Masters and Johnson made their assessments with an artificial penis that could mechanically imitate natural coitus and by “direct observation”—the introduction of a speculum and bimanual palpation.4,5 Their most remarkable observations regarding sexual arousal in the woman were the backwards and upwards movements of the anterior vaginal wall (vaginal tenting) and a 50-100% greater volume of the uterus. This increase disappeared 10-20 minutes after orgasm. When sexual excitement without orgasm occurred, the volume returned to normal in 30-60 minutes. Masters and Johnson presumed that the greater volume of the uterus was due to engorgement with blood. However, they qualified their presumption: “In view of the artificial nature of the equipment, legitimate issue may be raised with the integrity of observed reaction patterns.”4

In 1992 Riley et al published an ultrasound study on copulation.6 The images were of relatively poor quality as they used hand held, self scanning equipment, and none of the images was overview. We used magnetic resonance imaging to study the anatomy and physiology of human sexual intercourse. Our search started in 1991 when one of us (PvA) saw a black and white slide of a midsagittal magnetic resonance image of the mouth and throat of a professional singer who was singing “aaa.” He remembered Leonardo's drawing and wondered whether it would be possible to take such an image of human coitus. We decided to try, as an ad hoc “instrument-oriented” study, despite the unscientific and other irrelevant reactions we expected and received: honi soit, qui mal y pense.

Magnetic resonance imaging had already been used as a diagnostic tool to study erectile impotence7; it is particularly attractive for this kind of study because it produces images with exquisite anatomical detail that are clearer than those obtained with ultrasonography or radiography, and—as far as we know—it is safe. The aim of the study was initially to find out whether taking images of the male and female genitals during coitus is feasible, and later whether former and current ideas about the anatomy during sexual intercourse and during female sexual arousal are based on assumptions or on facts.

Subjects and methods

The participants (pairs of men and women) were recruited by personal invitation and through a local scientific television programme. Respondents were invited to participate if they met the following criteria: older than 18 years, intact uterus and ovaries, and a small to average weight/height index. The experimental procedure was explained in a letter sent to respondents along with an informed consent form. Participants were assured confidentiality, privacy, anonymity, and the possibility of withdrawing from the study at any time. After written informed consent had been obtained, the participants were invited to come for a scan when the equipment was available on a Saturday.

The tube in which the couple would have intercourse stood in a room next to a control room where the searchers were sitting behind the scanning console and screen. An improvised curtain covered the window between the two rooms, so the intercom was the only means of communication. Imaging was first done in a 1.5 Tesla Philips magnet system (Gyroscan S15) and later in a 1.5 Tesla magnet system from Siemens Vision. To increase the space in the tube, the table was removed: the internal diameter of the tube is then 50 cm. The participants were asked to lie with pelvises near the marked centre of the tube and not to move during imaging. After a preview, 10 mm thick sagittal images were taken with a half-Fourier acquisition single shot turbo SE T2 weighted pulse sequence (HASTE). The echo time was 64 ms, with a repetition time of 4.4 ms. With this fast acquisition technique, 11 slices of relatively good quality were obtained within 14 seconds.

The volunteers were shown the equipment in the two rooms, and personal and gynaecological histories were taken. The experimental procedure was explained, and all investigators left the imaging room. After a preliminary image for positioning the true pelvis of the woman was taken, the first image was taken with her lying on her back (image 1). Then the male was asked to climb into the tube and begin face to face coitus in the superior position (image 2). After this shot—successful or not—the man was asked to leave the tube and the woman was asked to stimulate her clitoris manually and to inform the researchers by intercom when she had reached the preorgasmic stage. Then she stopped the autostimulation for a third image (image 3). After that image was taken the woman restarted the stimulation to achieve an orgasm. Twenty minutes after the orgasm, the fourth image was taken (image 4). At the end of the experiment, the images were evaluated in the presence of the participants.

Results

Thirteen experiments were performed with eight couples (three couples performed two experiments each) and three single women. The table shows age, weight/height index, parity, type of contraception, female orgasm (yes/no), and the depth of penetration (partial or complete). No women reported having a “g-spot” or producing female ejaculation during orgasm. On two Saturdays in 1991 (experiments 1 and 2) the first couple succeeded with complete penetration that lasted sufficiently long for the images to be taken. The Philips 1.5 Tesla magnet system at that time required a relatively long acquisition time (52 seconds) and had a relatively poor signal:noise ratio. This gave low quality images with many movement artefacts. In 1996 the Siemens Vision 1.5 Tesla magnet system became available and provided the opportunity to continue our search for sharp images. Six couples succeeded in partial, though not complete, penetration (experiments 3 and 7-11). In 1998 sildenafil (Viagra) became available in the Netherlands. The two couples in experiments 9 and 11 were invited to repeat the procedure one hour after the man had taken one 25 mg tablet of sildenafil. They succeeded with complete penetration that lasted long enough (12 seconds) for sharp images to be taken (experiments 12 and 13).

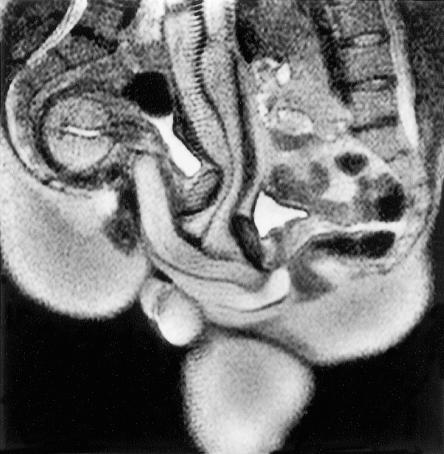

Figure 3 shows a midsagittal image of the anatomy of sexual intercourse with the woman lying on her back and the man on top of her. The root of the penis (1/3 of the length) and the erect pendulous body (2/3 of the length) are visible. The pendulous part of the erect penis moved upwards at an angle of about 120° to the root of the penis, and almost parallel to the woman's spine. In all the experiments this phenomenon occurred in this coital position and was not related to the depth of penetration. In complete penetration the penis filled up the anterior fornix (experiments 1, 2, and 13) or the posterior fornix (experiment 12; fig 3). During intromission the pubic bones of the men and the women did not approach each other closely: the female pubic bone stayed about 4 cm cranial to that of the male. The uterus was raised by 2.4 cm. The changed configuration of the bladder was caused by penile stretching of the anterior vaginal wall during intromission, plus the raising of the uterus and the increase in bladder size as it filled. The subjective level of sexual arousal of the participants, men and women, during the experiment was described afterwards as average.

Figure 3.

Midsagittal image of the anatomy of sexual intercourse (experiment 12). P=penis, Ur=urethra, Pe=perineum, U=uterus, S=symphysis, B=bladder, I=intestine, L5=lumbar 5, Sc=scrotum

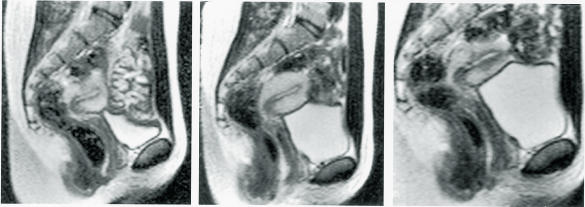

Eight women had a complete sexual response during sexual stimulation (experiments 4-11) and these women described their orgasm as “superficial.” The sexual response of one of these women is shown in figure 4. In the pre-orgasmic phase the anterior vaginal wall lengthened by 1 cm and the uterus rose within the pelvis. This is a typical response in all experiments except one (experiment 10). During sexual arousal without coitus, the position and size of the uterus hardly changed. It was not possible on these magnetic resonance images to distinguish between the vaginal wall, the urethra, and the clitoris. These images did not show widening of the vaginal canal, structures suggesting a Gräfenberg spot, or a separate reservoir of fluid indicating “female ejaculation.”

Figure 4.

Midsagittal images of sexual response in a multiparous woman (experiment 9): (left) at rest; (centre) pre-orgasmic phase; (right) 20 minutes after orgasm

Discussion

In Sex and the Human Female Reproductive Tract Levin stated: “The scientific study of the interaction of human genitals during coitus and after ejaculation with and without female orgasm has always been difficult and controversial with ethical, technical and social problems.”8 We experienced this personally. It took years, a lobby, undesired publicity, and a godsend (two tablets of sildenafil 25 mg) to obtain our images. They show that such pictures are feasible and add to our knowledge of anatomy.9

We did not foresee that the men would have more problems with sexual performance (maintaining their erection) than the women in the scanner. All the women had a complete sexual response, but they described their orgasm as superficial. Only the first couple was able to perform coitus adequately without sildenafil (experiments 1 and 2). The reason might be that they were the only participants in the real sense: involved in the research right from the beginning because of their scientific curiosity, knowledge of the body, and artistic commitment. And as amateur street acrobats they are trained and used to performing under stress.

Anatomy revealed

The hypothesised anatomy of human coitus, as drawn by Leonardo da Vinci in about 1493 and by Dickinson in 1933, could be tested with magnetic resonance imaging. According to our images, the caudal position of the male pelvis during intercourse, the potential size of the bulb of the corpus spongiosum, and the capacity of the penis in erection to make an angle of around 120° to the root of the penis, enabled penetration along the bottom of the symphysis up to the woman's promontorium (fig 3) or to the middle part of the sacrum (fig 4) almost parallel to her spine. The “hidden” position of the root of the penis must have been the reason for the difference between the angle of penetration as envisaged by Dickinson and the penetration angle on our images. The images showed that during “missionary position” intercourse the penis is not straight, as drawn by Leonardo. It has the shape of a boomerang and not of an S as envisaged by Dickinson. Leonardo and Dickinson clearly underestimated the size of the root of the penis. Scanning of the position of the human genitals during coitus gives a convincing impression of the enormous size of the average penis in erection (root plus pendulous part is 22 cm) and of the volume of vaginal and pelvic space required by the pendulous part of the penis.

Contemporary scientific knowledge about internal genital changes during female sexual arousal relates mainly to the vagina (thickening of the vaginal wall due to vasodilation, lubrication, widening of the vaginal cavity), the urethra (possible engorgement of the vascular tissue of the urethra), and the uterus (upwards movement of the uterus=tenting effect+change in position of the uterus+change in size of the uterus). Recent research on the anatomical relation between urethra and clitoris showed that the perineal urethra is embedded in the anterior vaginal wall and is surrounded by erectile tissue in all directions except posteriorly where it relates to the vaginal wall.10 The bulbs of the vestibule directly relate to the other clitoral components and the urethra. Details of the vaginal wall, the urethra, and the bulbs of the vestibule were unfortunately beyond the resolution of our current equipment. However, we were able to see displacement of the uterus (upwards) and lengthening of the anterior vaginal wall and hardly any change in the position of the uterus during sexual arousal, unless it was caused by intromission of the penis.

In contrast to the findings of Masters and Johnson,4 our images did not show an increase in the size of the uterus during sexual arousal. These observations are not surprising. From an anatomical and physiological point of view there is no basis for a 50-100% increase in the volume of the uterus in such a short time. Masters and Johnson made their observations with bimanual palpation. Their interpretation may have been caused by the raising of the uterus or filling of the bladder during their experiments.

Changes during sexual arousal

Magnetic resonance imaging showed strikingly that during female sexual arousal changes occurred in the anterior vaginal wall. These changes took place in the vaginal wall itself (the engorgement as such is not visible on the images), through the raising of the uterus, displacement of the uterus caused by penetration of the penis, and through gradual filling of the bladder. Histological studies11,12 and immunohistochemistry13 have shown that the anterior wall of the vagina has denser innervation than the posterior wall. This is supported by clinical studies14,15 and research into vaginal sensitivity to electric stimuli16 in which the anterior vaginal wall—with the urethra behind it—was found to be relatively sensitive. Hoch's concept of a clitoral-vaginal sensory arm of the orgasmic reflex refers specifically to the anterior vaginal wall and the deeper tissues—the urinary bladder, the periurethral tissues, and Halban's fascia15—and our images support this.

Conclusion

What started as artistic and scientific curiosity has now been realised. We have shown that magnetic resonance images of the female sexual response and the male and female genitals during coitus are feasible and beautiful; that the penis during intercourse in the “missionary position” has the shape of a boomerang and not of an S as drawn by Dickinson; and that, in contrast to the findings of Masters and Johnson, there was no evidence of an increase in the volume of the uterus during sexual arousal.

What is already known on this topic

It has been extremely difficult to investigate anatomical changes during the act of coitus and the female sexual response

Modern magnetic resonance imaging allows exploration of aspects of living anatomy

What this paper adds

Taking MR images of the male and female genitals during coitus is feasible

During ‘missionary position’ intercourse the penis has the shape of a boomerang

During female sexual arousal without intercourse the uterus rises and the anterior vaginal wall lengthens

The size of the uterus does not increase during sexual arousal

The Polish-German physician and philosopher Ludwik Fleck (1896-1961) used images of female genital anatomy to illustrate the cultural conditioning of scientific knowledge. In his treatise Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact he states: “In science, just as in art and in life, only what is true to culture is true to nature.”17 Magnetic resonance images, objective as they are, show the anatomy of human coitus and the female sexual response that is true to nature.

Table.

Magnetic resonance imaging during coitus (8 couples) and sexual arousal (11 women)

| Experiment | Age (man/woman) | Weight/ height (man/ woman) | No of children | Contraception | Female orgasm | Penetration | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 41/40 | 0.33/0.39 | 1 | Vasectomy | No | Complete | Movement artefact (1991) |

| 2 | 43/42 | 0.33/0.39 | 1 | Vasectomy | No | Complete | Movement artefact (1993) |

| 3 | 21/20 | 0.31/0.30 | 0 | Oral | No | Partial | Movement artefact (1996) |

| 4 | 23 | 0.35 | 0 | Oral | Yes | No | No partner |

| 5 | 40 | 0.40 | 3 | No | Yes | No | No partner |

| 6 | 35 | 0.37 | 0 | Oral | Yes | No | No partner |

| 7 | 20/21 | 0.32/0.30 | 0 | Oral | Yes | Partial | No |

| 8 | 23/21 | 0.38/0.34 | 0 | Oral | Yes | Partial | No |

| 9 | 28/27 | 0.35/0.30 | 0 | No | Yes | Nearly complete | No |

| 10 | 24/21 | 0.39/0.40 | 0 | Oral | Yes | Nearly complete | Uterus in retroversion |

| 11 | 26/26 | 0.35/0.33 | 0 | Oral | Yes | Nearly complete | No |

| 12 | 25/22 | 0.39/0.40 | 0 | Oral | No | Complete | Sildenafil 25 mg; uterus in retroversion (1998) |

| 13 | 28/28 | 0.35/0.33 | 0 | Oral | No | Complete | Sildenafil 25 mg |

Acknowledgments

We thank our volunteers for their cooperation, laughter, and permission to publish intimate MR images of them; those hospital officials on duty who had the intellectual courage to allow us to continue this search despite obtrusive and sniffing press hounds; Professor J Kremer for his encouragement to use the scanner to study female sexology and for his critical reading the typescript; and Professor W Mali for offering the use of equipment at the University Hospital Utrecht. P van Andel does not want to be acknowledged for his idea of using MRI to study coitus. He excuses himself by quoting the French romantic poet Alphonse de Lamartine (1790-1869): “C'est singulier! Moi, je pense jamais, mes idées pensent pour moi.”

Footnotes

Funding:No additional funding.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Chianchi M. Leonardo, the anatomy. Florence: Giunti; 1998. p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark K, Pedretti C. The drawings of Leonardo da Vinci in the collection of Her Majesty the Queen at Windsor Castle. London: Phaidon; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickinson RL. Human sex anatomy, a topographical hand atlas. 2nd ed. London: Baillière, Tindall and Cox; 1949. pp. 84–109. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human sexual response. Boston: Little, Brown; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson VE, Masters WH, Lewis KC. The physiology of intravaginal contraception failure. In: Calderone MS, editor. Manual of contraceptive practice. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1964. pp. 138–150. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riley AJ, Lees W, Riley EJ. An ultrasound study of human coitus. In: Bezemer W, Cohen-Kettenis P, Slob K, Van Son-Schoones N, editors. Sex matters. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1992. pp. 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sohn MH, Wein B, Bohndorf K, Handt S, Jakse GIJ. Dynamic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with paramagnetic contrastagens: a new concept for evaluation of erectile impotence. Impotence Res. 1991;3:36–48. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levin RJ. Sex and the human female reproductive tract—what really happens during and after coitus. Int J Impotence Res. 1998;10(suppl 1):14–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Andel P. Anatomy of the unsought finding. Serendipity: origin, history, domains, traditions, appearances and programmability. Br J Phil Sci. 1994;45:631–648. [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Connell HE, Hutson JM, Anderson CR, Plenter RJ. Anatomical relationship between urethra and clitoris. J Urol. 1998;159:1892–1897. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)63188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krantz KE. Innervation of the human vulva and vagina. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;12:382–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minh MH, Smadja A, De Sigalony JPH, Aetherr JF. Role du fascia de Halban dans la physiologie orgasmique feminime. Cahiers de Sexuol Clin. 1981;7:169. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hilleges M, Falconer C, Ekman-Ordeberg G, Johanson O. Innervation of the human vaginal mucosa as revealed by PGP 9.5 immunohistochemistry. Acta Anatomica. 1995;153:119. doi: 10.1159/000147722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alzate H, Londono ML. Vaginal erotic sensitivity. J Sex Marital Ther. 1984;10:49–56. doi: 10.1080/00926238408405789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoch Z. Vaginal erotic sensitivity by sexual examination. Acta Obstet Scand. 1986;5:767–773. doi: 10.3109/00016348609161498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weijmar Schultz WCM, Van de Wiel HBM, Klatter JA, Sturm BE, Nauta J. Vaginal sensitivity to electric stimuli, theoretical and practical implications. Arch Sex Behav. 1989;18:87–95. doi: 10.1007/BF01543115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleck L. Genesis and development of a scientific fact. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1979. p. 35. . (Translation of Entstehung und Entwicklung einer Wissenschaftliche Tatsache: Einführung in die Lehre vom Denkstil und Denkcollectiv. Basel: Benno Schwabe, 1935.) [Google Scholar]