Abstract

We have shown previously that exacerbation of corneal scarring (CS) in HSV-1 glycoprotein K (gK) immunized mice was associated with CD8+ T cells. In this study, we investigated the type and the nature of the immune responses that are involved in the exacerbation of CS in gK-immunized animals. BALB/c mice were vaccinated with baculovirus expressed gK, gD, or mock-immunized. Twenty-one days after the third immunization, mice were ocularly infected with 2×105 PFU/eye of virulent HSV-1 strain McKrae. Infiltration of the cornea by CD4+, CD8+, CD25+, CD4+CD25+, CD8+CD25+, CD19+, CD40+, CD40L+, CD62L+, CD95+, B7-1+, B7-2+, MHC-I+, and MHC-II+ cells were monitored by immunohistochemistry, qRT-PCR and FACS at various times post infection (PI). This study demonstrated for the first time that the presence of CD8+CD25+ T cells in the cornea is correlated with exacerbation of CS in the gK-immunized group.

Keywords: Immunostaining, TaqMan qRT-PCR, Cornea, FACS

INTRODUCTION

Herpes simplex type 1 (HSV-1) encodes at least 85 genes (McGeoch et al., 1988) and 11 of these genes code for glycoproteins. Some of these glycoproteins act as major targets and inducers of humoral and cell-mediated responses (Burke, 1991; Burke, 1992; Dix and Mills, 1985; Ghiasi et al., 1994a). HSV-1 glycoprotein K (gK) is one of the essential HSV-1 glycoproteins and is encoded by the UL53 open reading frame (Debroy, Pederson, and Person, 1985; McGeoch et al., 1988). The gK gene encodes a protein of 338 aa that is highly conserved in α-herpesviruses (Debroy, Pederson, and Person, 1985; McGeoch et al., 1988). Studies using insertion/deletion mutants of this gene have shown the importance of the gK protein in virion morphogenesis and egress (Foster and Kousoulas, 1999; Hutchinson and Johnson, 1995; Hutchinson, Roop-Beauchamp, and Johnson, 1995). Furthermore, deletion of gK results in the formation of extremely rare microscopic plaques, indicating that gK is required for virus replication (Foster and Kousoulas, 1999; Hutchinson and Johnson, 1995), which is supported by the observation that gK-deficient virus can only be propagated on complementing cells which express gK (Foster and Kousoulas, 1999; Hutchinson and Johnson, 1995).

We previously demonstrated that immunization of mice with gK, but not with any of the other HSV-1 glycoproteins, resulted in exacerbation of corneal scarring (CS) and herpetic dermatitis following ocular HSV-1 infection (Ghiasi et al., 1995a; Ghiasi et al., 1994a). We also showed that transfer of whole serum or purified IgG from gK-immunized mice to naive mice resulted in the same severe exacerbation of CS following ocular HSV-1 infection as seen in gK-immunized mice (Ghiasi et al., 1997a). In contrast, adoptive transfer of T cells from gK-immunized mice to naive mice did not result in exacerbation of CS following ocular HSV-1 infection (Ghiasi et al., 1997a). More recently we have shown that depletion of CD8+ T cells in gK immunized mice reduced exacerbation of gK-induced CS in ocularly infected mice (Osorio et al., 2004). We have also demonstrated that a recombinant HSV-1 virus expressing two additional copies of gK exacerbated CS, suggesting that gK over-expression is pathogenic (Mott et al., 2007c). In addition, we have recently demonstrated that the pathogenic region of gK is located within the signal sequence of gK (Mott et al., 2009; Osorio et al., 2007).

HSV-1 infections are among the most frequent serious viral eye infections in the U.S. and are a major cause of viral-induced blindness (Barron et al., 1994; Dawson, 1984; Hill, 1987; Liesegang, 1999; Liesegang, 2001; Wilhelmus et al., 1996). It is well established that HSV-1-induced CS and thus HSV-1-induced corneal blindness are the result of immune responses triggered by the virus (Brandt, 2005; Dix, 2002; Hendricks and Tumpey, 1990; Metcalf and Kaufman, 1976). The exact identity of the immune responses, including the fine specificity of the potentially harmful T-cell effectors expressing classic TCRαβ antigen receptors that lead to CS remains an area of intense controversy (Banerjee et al., 2002; Huster et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 1998). Depending on the body of literature referenced, one can conclude that CS is caused by T-cell dependent immune responses (CD4+, CD8+) (Doymaz and Rouse, 1992; Ghiasi et al., 1997b; Hendricks, Epstein, and Tumpey, 1989; Hendricks, Janowicz, and Tumpey, 1992; Mercadal et al., 1993) or by T-cell independent immune responses (macrophages, NK cells) (Brandt and Salkowski, 1992; Ghiasi et al., 2000a; Oakes et al., 1993; Tumpey et al., 1998a; Tumpey et al., 1998b). We have previously shown that in gK-immunized mice, exacerbation of CS was associated with the presence of CD8+ T cells (Osorio et al., 2004), and these CD8+ T cells could be CD25+ (regulatory T cells, T8reg) or CD25− (effector T cells). Thus, both CD8+CD25+ and CD8+CD25− T cells may contribute to exacerbation of CS in our gK model of CS.

To determine if the presence of CD8+CD25+ or CD8+CD25− T cells in the cornea of gK-immunized mice contributed to higher CS in infected mice, mice were vaccinated with gK (exacerbated CS), gD (protected from CS) or mock-vaccinated (moderate CS relative to gK). Following ocular infection, the corneas, spleen, and thymus of gK-immunized mice were harvested at various times post ocular infection and examined for the presence or absence of different immune factors by immunostaining, qRT-PCR and FACS analysis. Our results demonstrated that the presence of CD8+CD25+ T cells is associated with gK-immunization and thus, is correlated with the exacerbation of CS seen in gK-immunized mice, confirming our previously published study on T cell depletion (Osorio et al., 2004).

RESULTS

Immunohistochemical evidence of presence of CD8+CD25+ T cells in cornea of gK-immunized mice

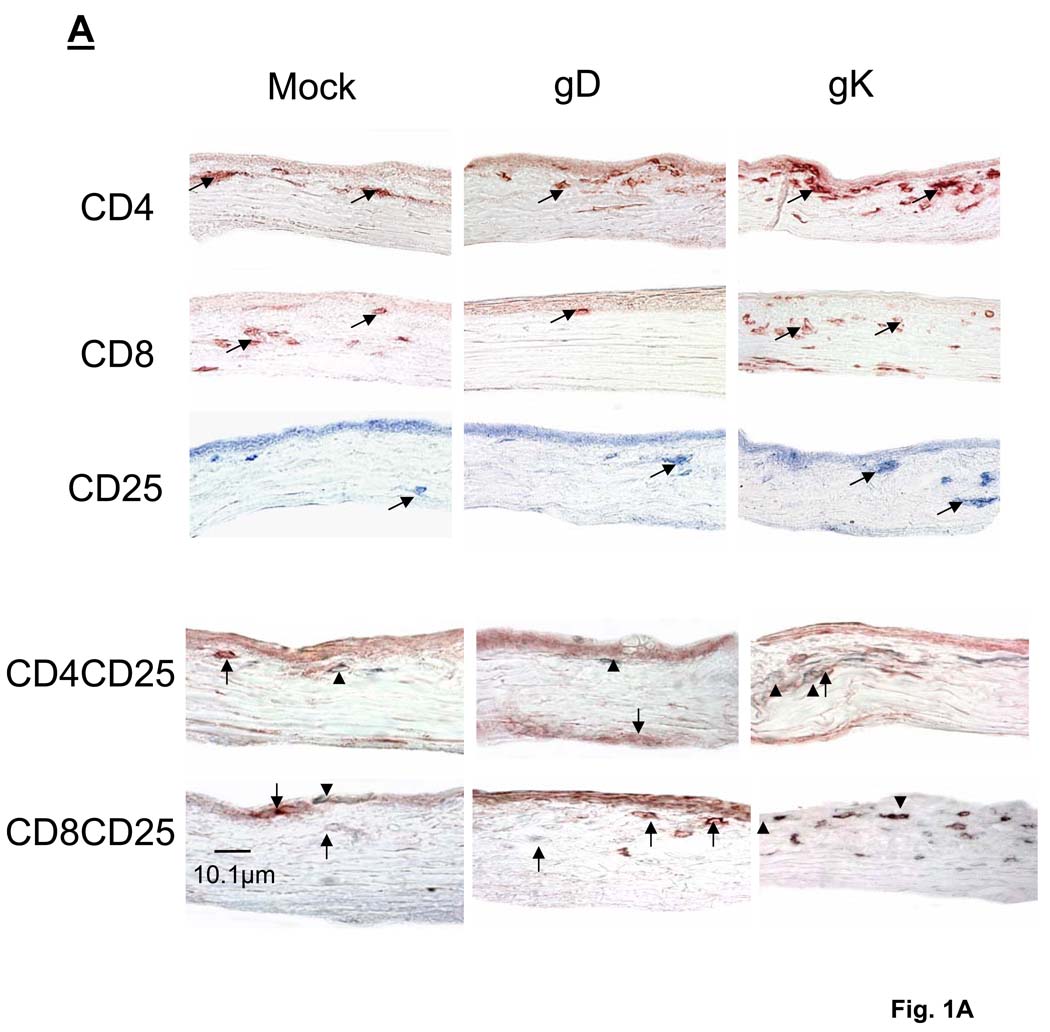

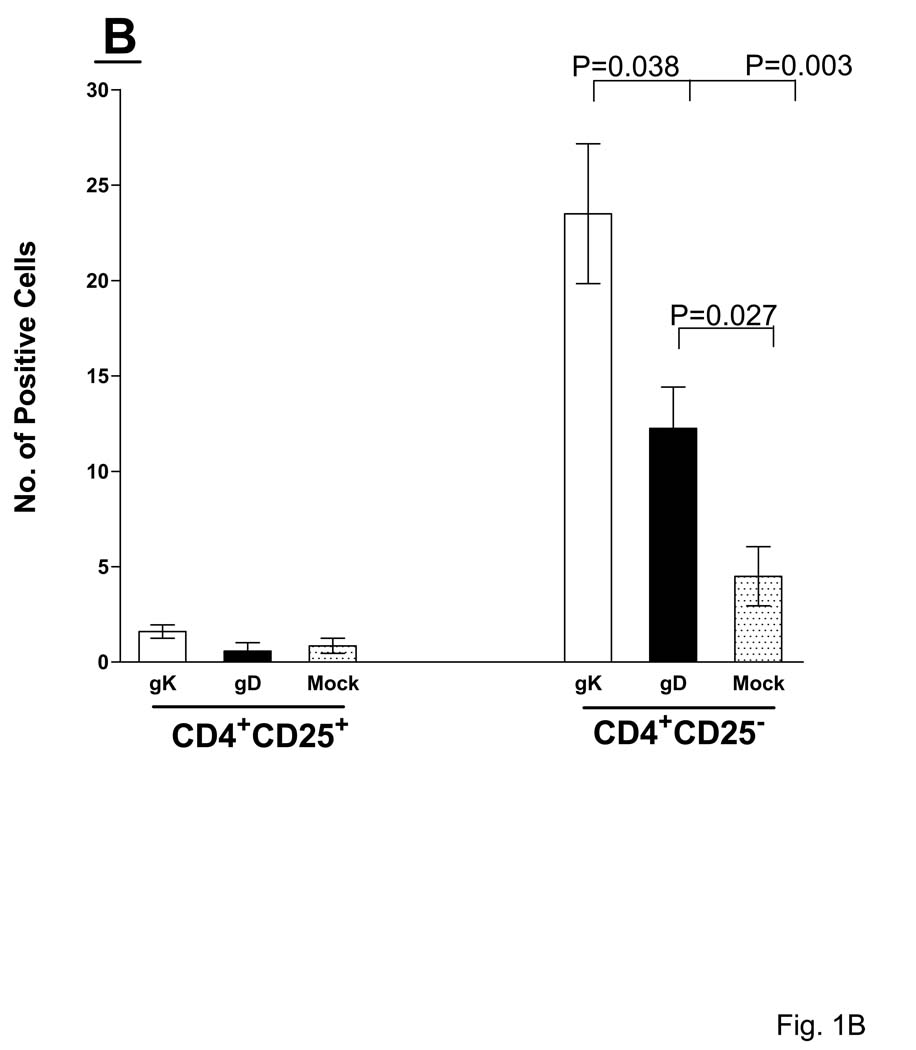

We have shown previously that following ocular HSV-1 infection, gD-immunized mice had little corneal disease, whereas gK-immunized mice had severely exacerbated corneal disease, and mock-immunized mice had a moderate level of corneal disease (Ghiasi et al., 1994b). To differentiate between local ocular immune responses that exacerbate HSV-1 induced eye disease and immune responses that provide protection against eye disease, mice were immunized three times with baculovirus expressed gD, gK, or mock-immunized and ocularly infected with HSV-1 as described in Materials and Methods. Based on our previous time course studies for the presence of infiltrates in corneas of infected mice (Ghiasi et al., 1995b), corneas were removed on day 5 PI, sectioned, and the presence of CD4+, CD8+, CD25+, B7-1+, B7-2+, CD19+, CD40+, CD40L+, CD62L+, CD95+, MHC-I+, and MHC-II+ cells were examined by single staining, whereas the presence of Treg cells (CD4+CD25+ and CD8+CD25+) were examined by double staining. Infiltrates of the cornea are quantified in Figure 1B, 1C and Figure 3B, while the images of those infiltrates that were different between gK and control groups are shown in Fig. 1A and Fig. 3A.

Fig. 1. Immunohistochemistry of T cell infiltrates in corneas of immunized mice on day 5 PI.

Mice were immunized and ocularly infected as described in Materials and Methods. Corneas from infected mice were removed at necropsy on day 5 PI, frozen, sectioned, then single or sequential double stained as described in Materials and Methods. (A) T cell infiltrates in cornea. Panels: Red: CD4+ or CD8+; Light blue:CD25+; and Dark-gray: CD4+CD25+ or CD8+CD25+ infiltrates. 60× direct magnification of single stain and 80× magnification of double stain. Arrows point to single stained cells while arrowheads indicate positive double staining. (B) Number of CD4+CD25+ infiltrates in cornea. For each double staining, the number of inflammatory CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25− infiltrates on the entire corneal section was counted double-blind for each of six eyes as 1B (above). (C) Number of CD8+CD25+ infiltrates in cornea. For each double staining, the number of inflammatory CD8+CD25+ and CD8+CD25− infiltrates on the entire corneal section was counted double-blind for each of six eyes. Each section represents the width and height of the entire cornea. The height of each bar represents the average number of cellular infiltrates from six eyes ± SEM.

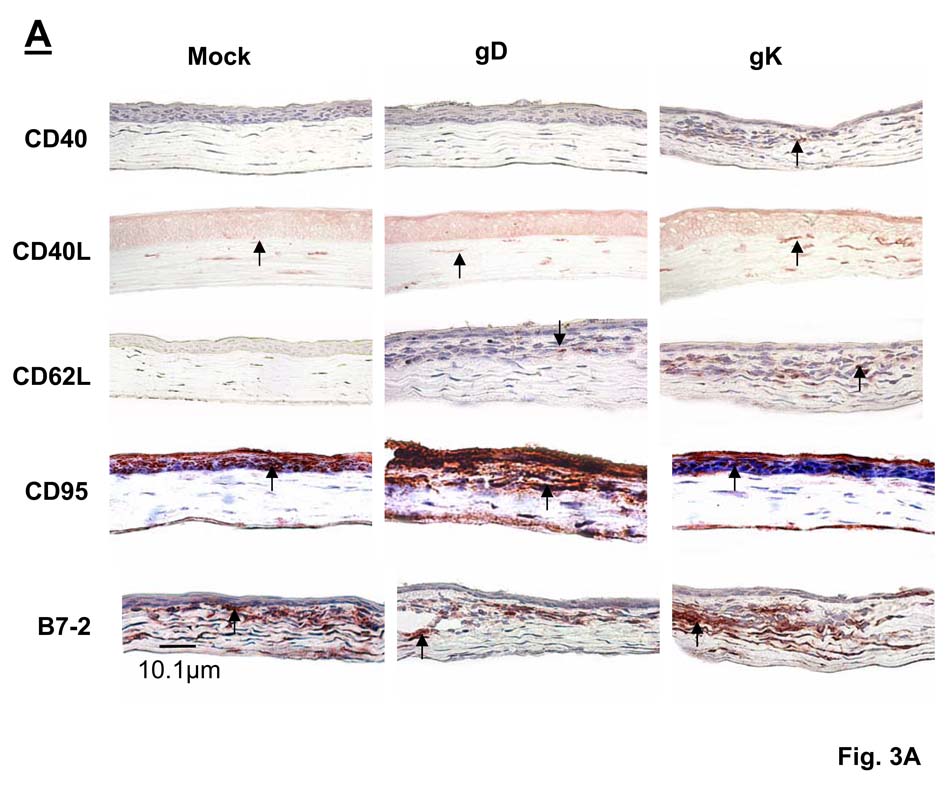

Fig. 3. Immunohistochemistry of various corneal infiltrates in immunized mice on day 5 PI.

(A) Corneal Infiltrates. BALB/c mice were immunized and infected as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Corneas were harvested on day 5 PI, snap frozen, and processed as described in Materials and Methods. Representative corneal sections stained with anti-B7-1, anti-B7-2, anti-CD19, anti-CD40, anti-CD40L, anti-CD62L, anti-CD95, anti-MHC-I, or anti-MHC-II are shown. Positive staining appears red, whereas tissue is counterstained blue. 60× direct magnification. (B). Quantification of corneal infiltrates. For each staining, the number of infiltrates on the entire corneal section was counted double-blind for each of six eyes. Each section represents the width and height of the entire cornea. The height of each bar represents the average number of cellular infiltrates from six eyes ± SEM.

The number of individual CD4+ and CD25+ infiltrates in corneas of the gK-immunized group were significantly higher compared to the mock-immunized group (Fig. 1B and Fig. 3B, P<0.05, Student’s T-test). The gD and gK groups contained large numbers of CD4+ T cells close to the corneal epithelial basement membrane and the anterior third of the stroma, whereas mock-immunized corneas only displayed CD4+ staining in the stroma (Fig.1A). Positive staining for CD25+ was most prevalent in the stroma of gK-immunized corneas, whereas there were significantly fewer detectable CD25+ T cells in the other groups (Fig. 3B, P<0.05, Student’s T-test). We observed extensive staining for CD8+ T cells in the stroma of the gK-immunized group (Fig. 1A), with both the gK- and mock-immunized groups having significantly more CD8+ cells than the gD-immunized group (Fig. 1C, P<0.05, Student’s T-test). Immunostaining for individual CD4+, CD8+, and CD25+ infiltrates as described above suggested elevation of these infiltrates in cornea of the gK-immunized group when compared to control groups. Thus, to determine if these T cells in corneas of gK-immunized mice were regulatory or effector, corneas of the three groups of mice were double-stained for the presence of CD4+CD25+ or CD8+CD25+ T cells. We detected 2.0±0.05 CD4+CD25+ cells in the gK-immunized group, which was not significantly different from either the gD- or mock-immunized groups (Fig, 1A and 1B, P>0.05, Student’s T-test). Significantly less CD8+CD25+ T cells were detected in the gD- and mock-immunized groups when compared to the gK-immunized group (Fig. 1C, P<0.05, Studen’ts T-test). The majority of CD25+ cells also stained positive for CD8 in the gK-immunized group (Fig. 1A). Since the major difference detected between the three groups was the presence of CD8+CD25+ T cells in corneas of the gK-immunized group, the mean numbers of CD8+CD25+ and CD8+CD25− (as well as the mean numbers of CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25−) T cells (from 6 eyes) were quantified and shown in Fig. 1B and 1C. In conclusion, we detected significantly more CD8+CD25+ T cells in gK-immunized corneas than mock- or gD-immunized corneas (Fig. 1C, P<0.0001, Student’s t-test). In contrast, no significant differences were detected between the mock- and gK-immunized groups for the presence of CD8+CD25− effector T cells (Fig. 1C, P>0.05, Student’s t-test) or CD4+CD25+ T cells (Fig. 1B, P>0.05, Student’s t-test). The above results suggested significant differences in the gK group for the presence of CD4+, CD8+, CD25+ and CD8+CD25+ T cells on day 5 PI.

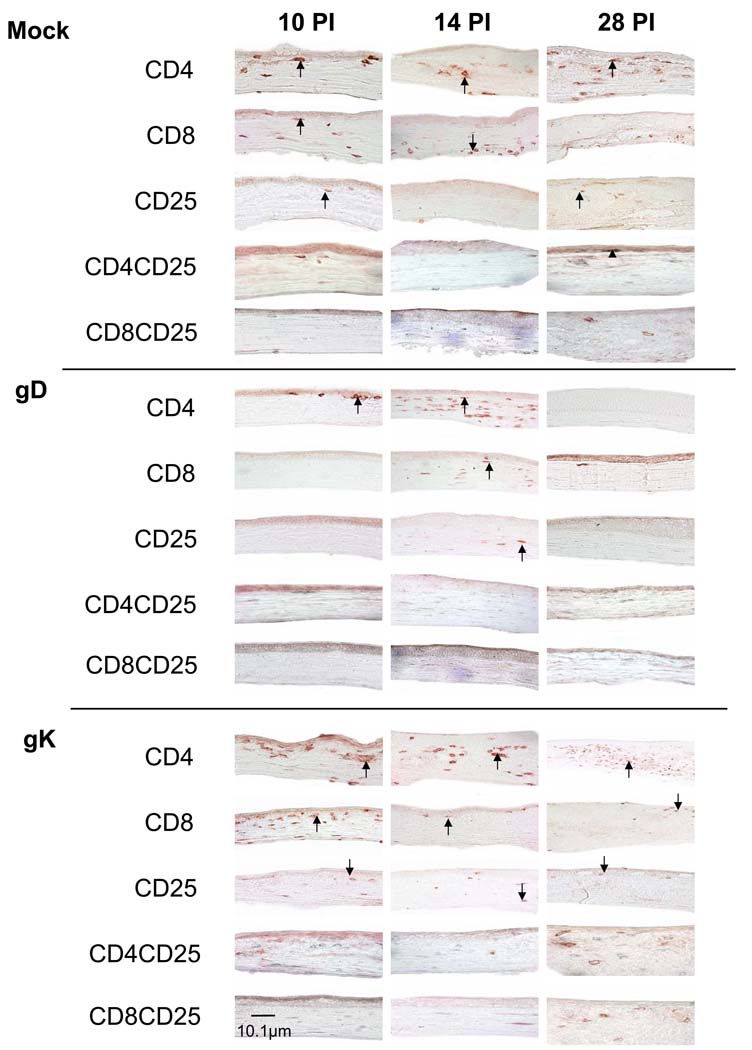

To determine how late these T cells are detected in corneas of gK-immunized mice, we evaluated the corneas from each group for the presence of CD4+, CD8+, CD25+, CD4+CD25+ and CD8+CD25+ on days 10, 14 and 28 PI (Fig. 2). CD4+ infiltrates were detected in corneas of all groups on days 10 and 14 PI (Fig. 2). However, by day 28 PI, the corneas of the gD-immunized group were clear of CD4+, CD8+ and CD25+ infiltrates. The mock-immunized corneas contained CD4+ and CD25+ as last as day 28 PI as well as CD4+CD25+, whereas the gK-immunized corneas contained CD8+ infiltrates in addition to CD4+ and CD25+ infiltrates up to day 28 PI (Fig. 2). Finally, while we observed CD8+CD25+ T cells on day 5 PI (Fig. 1A), no double stained CD8+CD25+ T cells were detected in any of the groups on days 10, 14, or 28 PI (Fig. 2). The presence of individual staining for CD25+ in the absence of double staining for CD4+CD25+ or CD8+CD25+ T cells on days 10, 14, or 28 PI is most likely due to the staining of CD25+ on activated B cells rather than T cells as described previously (Chen et al., 1994; Ortega et al., 1984).

Fig. 2. Immunohistochemistry of T cell infiltrates in corneas of immunized mice on days 10, 14, and 28 PI.

BALB/c mice were immunized and infected as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Corneas from infected mice were removed at necropsy on days 10, 14 and 28 PI, frozen, sectioned, then single CD4+, CD8+, or CD25+ staining or sequential double staining for CD4+CD25+ or CD8+CD25+ on corneal sections was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Individual positive staining for CD4+, CD8+ and CD25+ appears dark red, CD25+ appears light blue/gray, while double staining CD4+CD25+ or CD8+CD25+ appears dark gray due to the cell having both a dark red and light blue label. 60× direct magnification. Arrows indicate positive single staining while arrowheads indicate positive double staining.

In addition to staining for CD4+, CD8+, and CD25+ (Fig. 1A), the presence of B7-1, + B7-2+, CD19+, CD40+, CD40L+, CD62L+, CD95+, MHC-I+ and MHC-II+ infiltrates were examined by single staining of corneas of gK-, gD-, and mock-immunized mice. Representative corneas from the three vaccinated groups on day 5 PI are displayed in Fig. 3A and quantified in Fig. 3B. We observed no detectable differences in the levels of B7-1+, CD19+ or MHC-II+ infiltrates between the three groups. We observed significantly increased numbers of CD95+ infiltrates in the corneal epithelium, endothelium and stroma of gD-immunized mice compared to both mock- and gK-immunized groups (Fig. 3, CD95, P<0.05, Student’s t-test). Significantly increased expression of B7-2+ was observed in gK- and mock-immunized corneas compared to gD-immunized groups (Fig. 3, B7-2, P<0.05, Student’s T-test). In gK-immunized corneas there was extensive CD40+ staining in the stroma, whereas there was none detected in the mock- or gD-immunized group (Fig. 3, CD40, P<0.05, Student’s T-test). CD40L+ infiltrates were detected in the stroma of all groups; however there were significantly more positive cells detected in the gK-immunized group when compared to the mock and gD groups (Fig. 3, CD40L, P<0.05, Student’s T-test). There was also a significant increase in CD62L+ infiltrates in stroma of the gK-immunized compared to the other groups (Fig. 3, CD62L, P<0.05, Student’s T-test). Finally, there were high numbers of MHC-I+ infiltrates in mock- and gK-immunized corneas, whereas there was no observable MHC-I positive staining in gD-immunized corneas (Supplementary Fig. 2 and Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of infiltrates detected in cornea, spleen and thymus of immunized mice on day 5 PI.a

| CORNEA | SPLEEN | THYMUS | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infiltrate | Mock | gD | gK | Mock | gD | gK | Mock | gD | gK | ||

| CD4 | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ||

| CD8 | + | + | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ||

| CD25 | + | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | ||

| CD19 | − | − | − | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | ||

| CD40 | − | − | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ||

| CD40L | + | + | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | + | ++ | ||

| CD62L | − | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | ++++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | ||

| CD95 | ++ | +++ | ++ | ++++ | ++ | ++++ | ++++ | +++ | +++ | ||

| B7-1 | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + | ++ | ||

| B7-2 | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | +++ | ||

| MHC-I | ++ | − | ++++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ | ||

| MHC-II | − | + | + | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | ||

| CD4+CD25+ | + | + | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| CD8+CD25+ | + | − | ++ | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

Female BALB/c mice were immunized 3× with gK, gD, or mock. Immunized mice were infected with 2×105 PFU/eye of McKrae. Positive cells for each eye were counted in a double-blind fashion on day 5 PI. ++++>40 cells detected in each microscopic field; +++, > 30 cells detected in each microscopic field; ++, 29 to 10 cells in each field; +<10 cells detected in each field; and −, no cell detected in each field. ND, not determined.

In addition to the cornea, we also performed immunohistochemical analysis for the presence of the above infiltrates in the spleen (Supplementary Fig. 3) and thymus (Supplementary Fig. 4) of mock-, gD- and gK-immunized groups. Increased numbers of CD95+ cells were detected in the spleen of gK- and mock-immunized groups when compared to the gD-immunized group (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Table 1). In contrast, spleens from the gD group displayed more CD19+ cells than the other groups (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Table 1). Thymic sections from the gK-immunized group contained higher numbers of B7-1+, CD19+ and CD40L+ infiltrates when compared to the gD-immunized group (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Table 1). Finally, we observed increased expression of CD62L+ infiltrates in the gK-immunized group compared to the other groups in all tissues examined--cornea, spleen and thymus (Figs. 3B and Table 1).

A summary of immunostaining results for the presence of CD4+, CD8+, CD25+, B7-1+, B7-2+, CD19+, CD40+, CD40L+, CD62L+, CD95+, MHC-I+ and MHC-II+ infiltrates in gK, gD, and mock groups at various times PI are shown in Figure 3. These results suggest that: (i) in gK- immunized mice, elevation of CD8+, CD25+, CD8+CD25+, CD40+, CD40L+, B7-2+, CD62L+ and MHC-I+ correlated with exacerbation of CS (gK group) (ii) there was significantly increased expression of CD95+ in the CS protected group (gD-immunized mice) correlating this infiltrate with protection; and (iii) high numbers of CD4+ infiltrates did not correlate with eye disease since all groups had elevated numbers of CD4+ T cells.

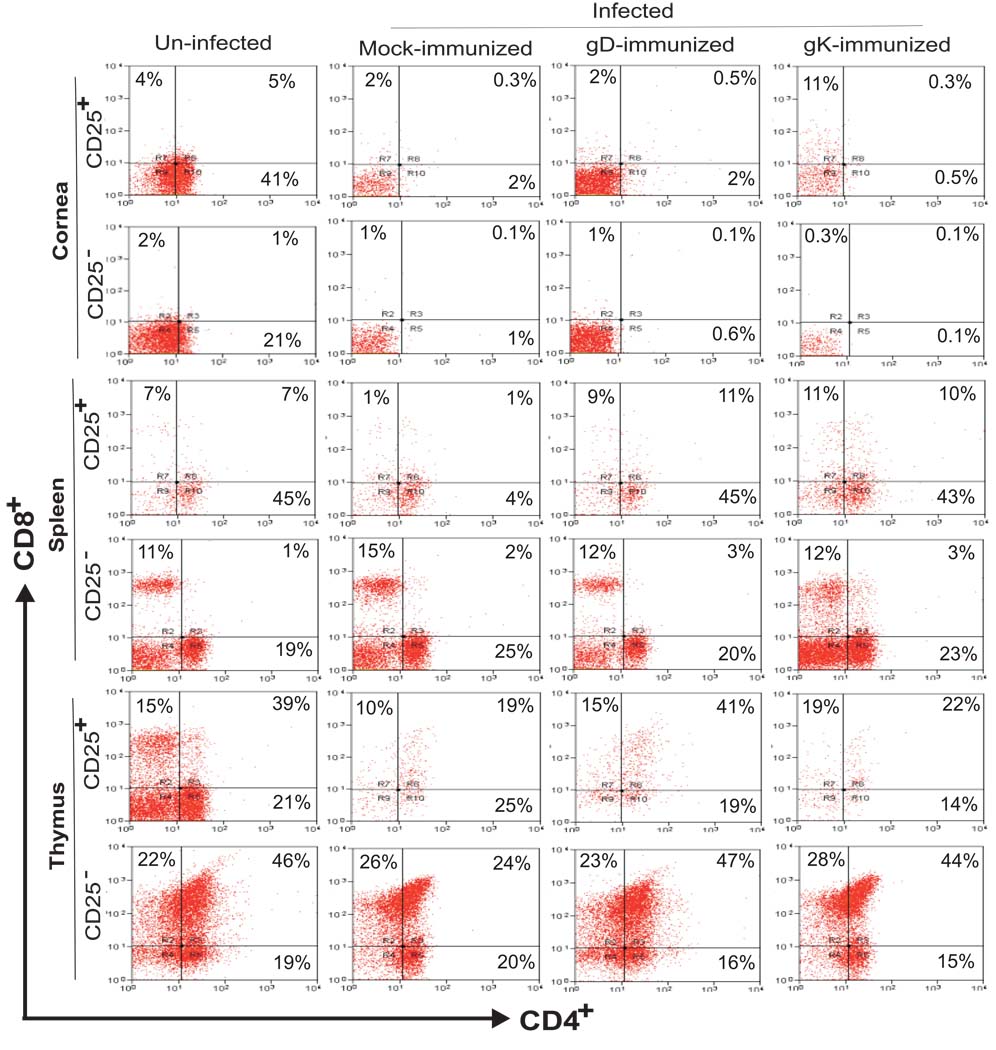

Detection of CD8+CD25+ T cells in the corneas of gK immunized mice by FACS

Our double staining results suggest that the level of CD8+CD25+ T cells in the cornea of gK immunized mice correlated with the increase of gK-induced CS. To confirm the immunostaining results with FACS, BALB/c mice were vaccinated 3× as described above. Three weeks after the final vaccination, all mice were infected ocularly with 2 × 105 PFU/eye of HSV-1 strain McKrae. Infected mice were sacrificed on day 5 PI, and CD4+CD25+ and CD8+CD25+ T cells in cornea, spleen, and thymus were analyzed by triple (CD4+CD8+CD25+) staining using FACS. The CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were gated for presence or absence of CD25+ expression (Fig. 4). Similar to immunostaining (Fig. 1A and Fig. 2) the FACS analysis indicates the expansion of CD25+ population of CD8+ T cells in cornea of gK-immunized and ocularly infected mice, but not in the uninfected or infected mock-immunized or gD-immunized mice (Fig. 4, CD25, top panels). Gating for CD25+ indicated that approximately 11% of the CD8+ T cells isolated from the gK-immunized cornea were CD8+CD25+, whereas negligible numbers of cells (2%) in corneas of mock or gD-immunized mice were CD8+CD25+ (Fig. 4, top row). However, no differences were detected for CD8+CD25− T cells for any of the groups, including gK-immunized mice (Fig. 4, middle panels). This is similar to the results presented in Fig. 1A, in which the majority of CD8+ T cells in the cornea of gK-immunized mice were CD25+. In contrast to the results in corneas, the population of CD8+CD25+ T cells was similar in lymphocytes isolated from thymus and spleens of gD-and gK-immunized groups as well as the uninfected group (Fig. 4). However, there was a decrease in the amount of CD8+CD25+ T cells in the mock-infected group, which could be attributed to lower cell vitality as the same trend was observed for all staining in the mock-immunized spleen (Fig. 4). Finally, there were no differences observed in the populations of CD4+CD25+ or CD4+CD25− cells in the spleen or thymus of any group (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Detection of CD8+CD25+ T cells in corneas of gK immunized mice by FACS.

BALB/c mice were immunized and infected as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Corneas, spleens, and thymuses were harvested on day 5 PI. The corneal tissues were cut into small pieces and then treated with 3 mg/mL of collagenase type I for 2.5 h at 37°C, with gentle passage 3–4 times through an eighteen-gauge syringe after the first hour. The single cell suspensions of total corneal cells, spleens, and thymuses were prepared as described (Osorio et al., 2005). Cell surface staining of single cell suspensions of cornea, spleen, and thymus from individual mice was accomplished using anti-CD4-Cy, anti-CD8a-PE, and anti-CD25-FITC mAbs. Three-color FACS analyses of isolated corneal cells were performed using a FACScan. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were gated for presence or absence of CD25 expression. Experiments were repeated twice.

In summary, our observations regarding CD8+CD25+ immunohistochemistry (Fig. 1) showed strong similarity with FACS analysis (Fig. 4). Both studies demonstrated an increase of CD8+CD25+ T cells in the cornea correlating with exacerbation of CS in gK-immunized group, whereas the levels of CD4+CD25+ CD4+CD25− and CD8+CD25− cells did not correlate with disease or protection.

Gene expression profiles in corneas and spleens of gK immunized and ocularly infected mice

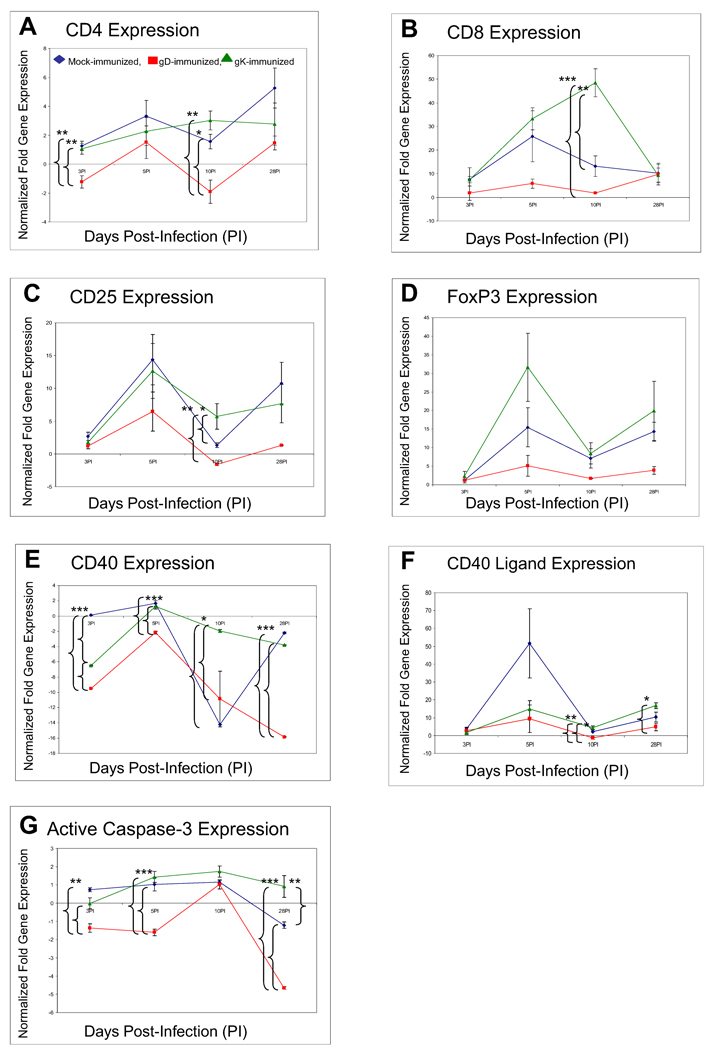

Our immunostaining and FACS results described above suggested that the elevation of CD4+, CD8+, CD25+, CD40+ and CD40L+ were correlated with exacerbation of CS in gK-immunized mice. Thus, the presence of these transcripts along with the transcripts for FoxP3 and active Caspase-3 were determined by qRT-PCR using total RNA isolated from corneas of gK-, gD-, and mock-immunized groups on days 3, 5, 10 and 28 PI. RNA isolated from spleens was used as a control and is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5.

Mock- and gK-immunized mice had significantly increased expression of corneal CD4 compared to gD-immunized mice on days 3 and 10 (Fig. 5A, CD4, P<0.01). gK-immunized mice had a statistically significant increased expression of CD8 compared to both mock- (P<0.001) and gD-immunized (P<0.01) mice on day 10 (Fig. 5B, CD8). There was a statistically significant increase in CD25 expression in the gK-immunized mice when compared to other groups on day 10 (P<0.05) (Fig. 5C, CD25). The results for CD4, CD8 and CD25 expression agree with our findings with immunohistochemistry over this time course (Fig. 2).

Fig. 5. qRT-PCR analyses of various inflammatory transcripts in corneas of gK-immunized mice at different times PI.

BALB/c mice were immunized and infected as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Total RNA from each mouse cornea was isolated on days 3, 5, 10, and 28 PI. CD4, CD8, CD25, CD40, CD40L, active Caspase-3, and FoxP3 expression in naive mice was used to estimate the relative expression of each transcript in corneas of mice in gK-, gD-, or mock-immunized group. GAPDH expression was used to normalize the relative expression of each transcript in corneas of gK-, gD-, or mock-immunized mice. Each point represents the mean ± SEM from 3 mice. Panels: A) CD4 transcript; B) CD8 transcript; C) FoxP3 transcript; D) CD25 transcript; E) CD40 transcript; F) CD40L transcript; and G) active Caspase-3 transcript. *, **, *** significantly different at P<0.05, P<0.01, and P<0.001, respectively.

In the gK-immunized group there was a statistically significant increased expression (P<0.05) of CD40 on all days compared to the gD-immunized group (Fig. 5E, CD40) and we observed a statistically significant increase in expression of CD40L in the gK-immunized group on days 10 (P<0.01) and 28 PI (P< 0.05) when compared to the gD-immunized group (Fig. 5F, CD40L). Finally, there was a statistically significant increase in active Caspase-3 expression in the mock- and gK-immunized groups compared to gD-immunized group on days 3 (P<0.01), 5 (P<0.001), and 28 (P<0.01) (Fig. 5G, active Caspase-3). Taken together, these data demonstrated a significant increase in the expression of CD8, CD25, active Caspase-3, CD40 and CD40L in mice presenting with CS during the course of HSV-1 infection. The immunohistochemistry results described above (Fig. 1 and Fig. 3) strongly agreed with the qRT-PCR patterns of increased CD8, CD25, CD40 and CD40L transcripts in CS mice (mock and gK-immunized groups) over that of gD-immunized groups (Fig. 5).

The expression of CD4, CD8, CD25, active Caspase-3, CD40 and CD40L transcripts were also examined in the spleens of each group during the course of infection (Supplementary Fig. 4). We observed a significant increase in the expression of FoxP3 and active Caspase-3 in the gK-immunized group when compared to the other groups (Supplementary Fig. 4, panels D and G). While we did not detect differential gene expression for CD4, CD8, CD25, CD40 or CD40L transcripts between spleens of the gK- and gD-immunized groups (Supplementary Fig. 4, panels A, B, C, E and F), we did detect a significant increase in the expression of all genes in the gK-immunized group when compared to the mock-immunized group (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Overall, the immunohistochemistry, FACS, and qRT-PCR data from the corneas were directly correlated with eye disease, whereas no direct correlation was detected between responses in spleen and thymus of infected mice with that of ocular pathology. Consequently, looking at the responses in the corneas is a better indicator of eye disease than the spleen or thymus.

DISCUSSION

HSV-1-induced CS, also broadly referred to as herpes stromal keratitis (HSK), can lead to blindness and HSV-1 is the leading cause of corneal blindness due to an infectious agent in developed countries (Dawson, 1984; Dix, 2002; Liesegang, 2001). It is well established and well accepted that HSV-1- induced CS is the result of immunopathology. Patients with enhanced immune responses develop the worst clinical manifestations of herpetic stromal disease (Corey and Spear, 1986; Schmid, 1988). Previously we have shown that exacerbation of CS in gK-immunized mice following ocular HSV-1 infection was associated with anti-gK antibody (Ghiasi et al., 1997a). In line with these results we have shown that sera from HSK individuals had higher anti-gK antibody titers than sera from seropositive individuals with no history of HSK despite having similar levels of neutralizing antibody titers and HSV-1 IgG (Mott et al., 2007b). Furthermore, similar to our animal studies (Ghiasi et al., 2000b), sera from HSK individuals induced antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE), whereas sera from non-HSK individuals did not induce ADE (Mott et al., 2007b). The ability of gK antibody to exacerbate corneal scarring following ocular HSV-1 infection may appear contradictory to exacerbation of corneal scarring in the presence of elevated levels of gK (i.e., an HSV-1 mutant that over expresses gK (Mott et al., 2007c) and ocular HSV-1 infection in the presence of a gK 8mer (Mott et al., 2009)). One possible explanation would be if gK antibody binds to gK and prevents its degradation. This would increase the half-life of gK, effectively increasing gK levels. Exacerbation of CS by gK antibody, over expression of gK, and addition of the gK 8mer may thus all exacerbate corneal scarring via a mechanism involving elevated gK levels.

The main goal of the present study was to determine the specific pathogenic immune response that leads to gK-induced exacerbation of CS in the presence of anti-gK antibody. We have observed different patterns of corneal infiltrates that correlate with high, moderate or no CS. Our results demonstrate that CD8+CD25+ T cell infiltrates at high level were present in corneas of the gK-immunized group and not in the mock- or gD-immunized groups. These results implicate CD8+CD25+ T cells but not CD8+CD25− effector T cells in the exacerbation of CS observed in gK-immunized mice. The Foxp3 gene has been correlated to CD4+CD25+ and CD8+CD25+ Treg cells (Campbell and Ziegler, 2007). In this study, while we did not detect significant differences, FoxP3 expression displayed a pattern of highest expression in the gK-immunized cornea, suggesting that the CD8+CD25+ T cells detected in the cornea of gK-immunized mice could be Treg. There is growing interest in the identification of Tregs in various pathologic conditions. These cells suppress immunity both non-specifically (Cosmi et al., 2003; Xystrakis et al., 2004) and specifically (Dhodapkar and Steinman, 2002; Gilliet and Liu, 2002). Similar to our finding, it was previously reported that CD8+CD25+ T cells could contribute to the disease process in ACAID (Lin et al., 2005), EAE (Chen, Inobe, and Weiner, 1995), Hashimoto’s disease (Watanabe et al., 2002), psoriasis (Kohlmann et al., 2004), and more recently in colorectal cancer tissue (Chaput et al., 2009). In this study we observed both CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25− T cells in corneas of all infected groups. While CD4+ T cells do not appear to play a role in the exacerbation of CS seen in gK-immunized mice, their contribution to some level of CS cannot be ruled out. Previously we have shown some level of CS in gK-immunized mice in the absence of CD8+ T cells (Osorio et al., 2004).

Our findings with regards to elevation of CD8+CD25+ T cells in cornea of mice immunized with gK are interesting in light of our previous study, in which adoptive transfer of T cells from gK immunized mice did not produce exacerbation of corneal scarring following HSV-1 infection (Ghiasi et al., 1997a), thus indicating that gK primed T cells alone are not responsible for this immunopathological reaction. We also showed that passive transfer of sera from gK immunized mice to naive mice produced an exacerbation of corneal scarring following ocular infection in the absence of gK primed T cells. In addition, we have shown that the presence of anti-gK antibody results in a higher viral load in the eyes due to ADE (Ghiasi et al., 2000b). This higher viral load presumably enhances the activity of CD8+ T cells, resulting in increased pathology (corneal scarring). Thus, corneal scarring induced by gK immunization appears to involve an indirect increase in the activation of CD8+CD25+ T cells resulting from ADE induced by anti-gK antibody.

Our immunohistochemical data demonstrated an increase in CD62L+ cells in the cornea, spleen and thymus of the gK-immunized group compared to the other groups suggesting T lymphocyte progression from naive to memory T cells. Lymphocyte cell surface molecule CD62L has been shown to play a crucial role in activation as well as specific homing of T cells to lymphoid organs (Arbones et al., 1994). Following activation, CD62L was reported to shed rapidly and cells migrate towards peripheral sites (Stamenkovic, 1995). However, this is not frequently observed after leukocyte activation (Ding et al., 2003; Usherwood et al., 1999). We have shown an elevation of CD62L in cornea of ocularly infected mice especially in the gK group supporting a putative role for CD62L in CD8+CD25+ induced CS.

The CD40-CD40L interaction is critical in cell mediated immunity and in generating T cell-dependent B cell responses in both animals and humans (Etzioni and Ochs, 2004; Kawabe et al., 1994). Previously it was shown that CD40 is involved in the generation of CD8+CD25+ Treg (Gilliet and Liu, 2002). In this study using both immunohistochemistry and qRT-PCR we have demonstrated that the levels of CD40 and CD40L are increased in corneas of gK- and mock-immunized mice compared to the gD-immunized group. Engagement of CD40 and CD40L between B and T cells allows for B cell activation, formation of germinal centers, subsequent class switch recombination and somatic hypermutation, and can lead to the production of antibody secreting plasma cells (van Kooten and Banchereau, 2000). The increase of CD40 and CD40L staining observed in the corneas of the gK group further confirm our previous study that humoral immunity is a necessary factor in the gK-associated exacerbated CS (Ghiasi et al., 1997a) following ocular infection with wild-type HSV-1. Our immunohistochemical data demonstrated positive staining for CD40L in small clusters within the splenic white pulp of both gK- and mock- immunized groups, whereas CD40L staining in the gD group was scattered and did not appear to be localized to germinal centers (Supplementary Fig. 3). This further suggests an active role for CD40-CD40L in the gK-induced humoral immune response. Additionally, it has been shown that the development of autoimmune uveitis is dependent on the CD40-CD40L interaction, as the disruption of this interaction via anti-CD40 antibody prevented disease development in an experimental autoimmune uveitis murine model (Bagenstose et al., 2005). Our results mimic this study as an absence of CD40 and a reduction of CD40L in the corneas of gD-immunized mice is correlated with protection against CS.

The expression of CD40 can also render lymphocytes resistant to CD95-activation induced cell death (AICD) as observed in EBV infection (Imadome et al., 2009) and in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (de Totero et al., 2004). Therefore, the inhibition of CD95-mediated cell death would allow an increased amount of unchecked T cells to stimulate the damaging immune response and exacerbate CS in gK-immunized animals. Furthermore, upregulation of CD40 and CD40L have already been implicated in human autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (Crow and Kirou, 2001) and inflammatory bowel disease (Danese, Sans, and Fiocchi, 2004). Similar to this study, it was shown previously that gD protected HSV-1 infected U937 cells from Fas-mediated apoptosis (Medici et al., 2003).

Taken together, our data suggests that the increased expression of CD40 and CD40L in the gK-immunized cornea could result in multiple and potentially chronic immune enhancing responses such as (i) increased cell-mediated immunity; (ii) activation of the humoral immune response; and (iii) lymphocyte apoptosis escape as CD40 could potentially render the infiltrating lymphocytes resistant to CD95-CD95L mediated cell death, creating an ACAID-like autoimmune response in the gK-immunized cornea.

In summary, our results suggest that CD40/CD40L acts as a cusp between B-cells and T cells in infected gK-immunized mice and demonstrates for the first time a correlation between gK-exacerbated CS and CD8+CS25+ T cells. Therapeutics directed against regulators of the network of costimulatory molecules identified in this study may provide useful treatment strategies against HSK.

Materials and Methods

Virus and cells

Plaque-purified McKrae, a neurovirulent HSV-1 strain, was grown in rabbit skin (RS) cell monolayers in minimal essential medium (MEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum as described previously (Ghiasi et al., 1994b).

Mice

BALB/cJ and C57BL/6 (female, 6 weeks old) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Animals were handled in accordance with the ARVO statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research under an approved IACUC protocol.

Immunization

Mice were immunized three times at three week intervals subcutaneously (SC) with baculovirus-expressed recombinant gK as described (Ghiasi et al., 1994b). As a positive control, additional BALB/c mice were immunized similarly with recombinant baculovirus expressing gD (Ghiasi et al., 1998). SC injections were done using complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) on day 0 and incomplete Freund's adjuvant IFA) on days 21 and 42. For SC injections, gK or gD expressed glycoproteins were emulsified 1:1 in CFA or IFA. Each vaccination consisted of extracts from 1 × 106 cells, which contained approximately 5 µg of gK or gD, based on the intensity of each expressed glycoprotein band on Coomassie Brilliant Blue stained gels. Mock-immunized mice were similarly inoculated three times with wild-type baculovirus infected Sf9 cells.

Ocular infection

Three weeks after the third immunization, mice were intraocularly infected with 2 ×105 PFU of HSV-1 McKrae, administered as a 2 µl eye drop into an eye that had no prior corneal scarification.

Immunostaining of cornea, spleen and thymus tissues

Five mice from each group were sacrificed on days 5, 10, 14, and 28 PI, and corneas, thymus and spleen were removed from each mouse at autopsy. The corneas, thymus and spleen were snap frozen in an isopentane-liquid nitrogen bath and stored at −80°C. Cryostat sections, 8–10 µm thick, were cut and air dried overnight, then fixed in reagent grade acetone for 3 min at 25°C. Immunostaining was performed using monoclonal antibodies against CD4 (clone GK1.5), CD8 (clone 53-6.7), CD25 (clone PC61), B7-1 (clone 1G10), B7-2 (clone H-200), CD19 (clone 1D3), CD40 (clone 3/23), CD40L (clone D1.61), CD62L (clone MEL-14), MHC-I (clone 28-14-8), MHC-II (clone 1-A/1-E) and CD95 (Fas) (clone X-20) (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The numbers of corneal cells immunopositive for each antibody were counted in a double-blind fashion from the entire corneal section. To reduce possible staining or sampling variability, three consecutive sections from each cornea were examined on each slide. One section was used to quantitate the number and distribution of cells. The second and third sections were used to verify these results, thereby confirming accuracy and ensuring a lack of artifacts due to staining or tissue manipulation. Only positively stained cells in the cornea, including epithelial, endothelial, and stromal layers, as well as the adjacent ciliary body were analyzed. Each section covers the entire height and width of the cornea and comprises approximately 1/20 of the depth of the cornea. Each group consisted of sample sections from 6 eyes, and each number represents the average cell count for each group. In addition to the single staining described above using biotinylated secondary antibody, some of the sections were double stained. Sequential double staining on corneal sections from the three groups was performed as follows; (1) Sections were incubated with CD25 mAb (2 hrs); (2) Biotinylated secondary antibody (1hr); (3) Avidin biotinylated enzyme complex (30 min); (4) After application of all the immunoreagent steps, peroxidase activity was developed in light-blue color. For CD4 or CD8 detection, CD4 or CD8 antibody, biotinylated secondary antibody, avidin biotinylated enzyme complex was added as above. As a final step peroxidase activity was developed in red. Thus, the individual color for CD25+ cell is light blue, for CD4+ or CD8+ cell is red, whereas the combined color of either CD25 and CD8 positive cells or CD25 and CD4 positive cells is dark gray. Supplementary Fig. 1 shows an example of CD4+ (red), CD25+ (light blue), and CD4+CD25+ (dark gray) cells in retina of gK-immunized and ocularly infected mice on day 5 PI to demonstrate the colorimetric differences that allowed either single label (red or light blue) to be distinguished from the double label (dark gray).

Flow Cytometry

BALB/c mice were immunized and infected as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Corneas, spleens, and thymuses were harvested on day 5 PI. The corneal tissues were cut into small pieces and then treated with 3 mg/mL of collagenase type I for 2.5 h at 37°C, with gentle passage 3–4 times through an eighteen-gauge syringe after the first hour. The single cell suspensions of total corneal cells, spleens, and thymuses were prepared as described (Osorio et al., 2005). Cell surface staining of single cell suspensions of cornea, spleen, and thymus from individual mice was accomplished using anti-CD4-Cy, anti-CD8a-PE, and anti-CD25-FITC mAbs. Three-color FACS analyses of isolated corneal cells were performed using a FACScan. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were gated for presence or absence of CD25 expression. Experiments were repeated twice.

RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

Corneas and spleens from immunized mice were collected on days 3, 5, 10, and 28 PI and immersed in RNAlater RNA stabilization reagent and stored at −80°C until processing. The corneas or spleen from each animal were processed for RNA extraction using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and RNeasy column cleanup (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). Briefly, frozen tissue was resuspended in TRIzol and homogenized, followed by addition of chloroform, and subsequent precipitation using isopropanol. The RNA was then treated with DNase I to degrade any contaminating genomic DNA followed by clean-up using a Qiagen RNeasy column as described in the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA yield from all samples was determined by spectroscopy (NanoDrop ND-1000, NanoDrop Technologies, Inc., Wilmington, DE). On average, the RNA yield from cornea and spleen samples was 1.8–3.75 µg and 50–80 µg, respectively. Finally, 500 ng of total RNA was reverse-transcribed with random hexamer primers and Murine Leukemia Virus (MuLV) Reverse Transcriptase contained in the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), as per the manufacturer's recommendations. All isolated corneas used for qRT-PCR and cell sorting described below were free of contamination from other parts of the mouse eye, vitreous fluid, and tears.

TaqMan Real-Time PCR

The expression levels of various target genes, along with the expression of the endogenous control gene GAPDH, were evaluated using commercially available TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) containing optimized primer and probe concentrations. Primer probe sets consisted of two unlabeled PCR primers and the FAM™ dye-labeled TaqMan MGB probe formulated into a single mixture. Additionally, all probes were designed to overlay an intron-exon junction to eliminate signal from any potential genomic DNA contamination. The assays used in this study were as follows: 1) CD4 ABI ASSAY I.D. Mm00442754_m1 – Amplicon Length = 72 bp; 2) CD8 (α chain) ABI ASSAY I.D. Mn01182108_m1 – Amplicon Length = 67 bp; 3) GAPDH ABI ASSAY I.D. Mm999999.15_G1 – Amplicon Length = 107 bp; 4) CD25 ABI ASSAY I.D Mm00434261_m1 – Amplicon Length = 123bp; 5) FoxP3 ABI ASSAY I.D. Mm00475164_m1 – Amplicon length = 80bp; 6) CD40 ABI ASSAY I.D Mm00441891_m1 – Amplicon Length = 68bp; 7) CD40L ABI ASSAY I.D Mm00441911_m1 – Amplicon Length = 120bp; and 8) Active-Caspase-3 ABI ASSAY I.D Mm01195084_m1 – Amplicon Length = 79bp. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using an ABI PRISM 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in 384-well plates and all reactions were performed in a final volume of 20 µl as described previously (Mott et al., 2007a). GAPDH expression was used to normalize the relative expression of CD4, CD8, CD25, CD40, CD40L, FoxP3, and active Caspase-3 in corneas or spleen. CD4, CD8, CD25, CD40, CD40L, FoxP3, and active Caspase-3 expression in naive mice was used to estimate the relative expression of each transcript in corneas or spleen of immunized and infected mice.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test and ANOVA were performed using the computer program Instat (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) to analyze protective parameters. Results were considered statistically significant when the P value was <0.05.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Fig. 1. Single and double peroxide immunohistochemistry in BALB/c eye. BALB/c mice were immunized and infected as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Eyes were removed from each animal on day 5 PI and processed for presence of CD4+ (red), CD25+ (blue) and CD4+CD25+ (dark gray) by immunohistochemistry. Colorimetric differences in peroxide staining are evident to allow distinction between single-stained and double-stained cells. 60× direct visualization.

Supplementary Fig. 2. MHC-1 and MHC-II peroxide immunohistochemistry in BALB/c cornea. BALB/c mice were immunized and infected as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Eyes were removed from each animal on day 5 PI and processed for presence of MHC-I and MHC-II by immunohistochemistry. 60× direct visualization of cornea.

Supplementary Fig. 3. Splenic infiltrates following HSV-1 ocular infection of immunized mice. BALB/c mice were immunized and infected as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Spleens were harvested on day 5 PI, snap frozen, and processed as described in Materials and Methods. Representative spleen sections were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD25, anti-B7-1, anti-B7-2, anti-CD19, anti-CD40, anti-CD40L, anti-CD62L, anti-CD95, anti-MHC-I, or anti-MHC-II mAb. 60× direct magnification.

Supplementary Fig. 4. Thymic infiltrates following HSV-1 ocular infection of immunized mice. BALB/c mice were immunized and infected as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Thymuses were harvested on day 5 PI, snap frozen, and processed as described in Materials and Methods. Representative spleen sections were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD25, anti-B7-1, anti-B7-2, anti-CD19, anti-CD40, anti-CD40L, anti-CD62L, anti-CD95, anti-MHC-I, or anti-MHC-II mAb. 60× direct magnification.

Supplementary Fig. 5. Expression of CD4, CD8, CD25, CD40, CD40L, FoxP3 and active Caspase-3 transcripts in spleen of immunized and infected mice. BALB/c mice were immunized and infected as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Spleens were removed from each animal on days 5, 10, 14 and 28 post-infection were processed for RNA extraction. CD4, CD8, CD25, CD40, CD40L, Active Caspase-3 and FoxP3 expression in naive mice was used to estimate the relative expression of each transcript in corneas of mice in gK-, gD-, or mock- immunized groups. GAPDH expression was used to normalize the relative expression of each transcript in spleen of gK-, gD-, or mock-immunized mice. Each point represents the mean ± SEM from 3 mice. Panels: A) CD4 transcript; B) CD8 transcript; C) FoxP3 transcript; D) CD25 transcript; E) CD40 transcript; F) CD40L transcript and G) Active Caspase-3 transcript. *, **, *** significantly different at P<0.05, P<0.01, and P<0.001, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant EY13615 from the National Eye Institute to HG, EY13431 and Winnick Family Foundation awards to AVL.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Arbones ML, Ord DC, Ley K, Ratech H, Maynard-Curry C, Otten G, Capon DJ, Tedder TF. Lymphocyte homing and leukocyte rolling and migration are impaired in L-selectin-deficient mice. Immunity. 1994;1(4):247–260. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90076-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagenstose LM, Agarwal RK, Silver PB, Harlan DM, Hoffmann SC, Kampen RL, Chan CC, Caspi RR. Disruption of CD40/CD40-ligand interactions in a retinal autoimmunity model results in protection without tolerance. J Immunol. 2005;175(1):124–130. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee K, Deshpande S, Zheng M, Kumaraguru U, Schoenberger SP, Rouse BT. Herpetic stromal keratitis in the absence of viral antigen recognition. Cell Immunol. 2002;219(2):108–118. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(02)00601-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron BA, Gee L, Hauck WW, Kurinij N, Dawson CR, Jones DB, Wilhelmus KR, Kaufman HE, Sugar J, Hyndiuk RA, et al. Herpetic Eye Disease Study. A controlled trial of oral acyclovir for herpes simplex stromal keratitis. Ophthalmology. 1994;101(12):1871–1882. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(13)31155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt CR. The role of viral and host genes in corneal infection with herpes simplex virus type 1. Exp Eye Res. 2005;80(5):607–621. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt CR, Salkowski CA. Activation of NK cells in mice following corneal infection with herpes simplex virus type-1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33(1):113–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke RL. Development of a herpes simplex virus subunit glycoprotein vaccine for prophylactic and therapeutic use. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:S906–S911. doi: 10.1093/clind/13.supplement_11.s906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke RL. Contemporary approaches to vaccination against herpes simplex virus. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1992;179:137–158. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-77247-4_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DJ, Ziegler SF. FOXP3 modifies the phenotypic and functional properties of regulatory T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(4):305–310. doi: 10.1038/nri2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaput N, Louafi S, Bardier A, Charlotte F, Vaillant JC, Menegaux F, Rosenzwajg M, Lemoine F, Klatzmann D, Taieb J. Identification of CD8+CD25+Foxp3+ suppressive T cells in colorectal cancer tissue. Gut. 2009;58(4):520–529. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.158824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Ma A, Young F, Alt FW. IL-2 receptor alpha chain expression during early B lymphocyte differentiation. Int Immunol. 1994;6(8):1265–1268. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.8.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Inobe J, Weiner HL. Induction of oral tolerance to myelin basic protein in CD8-depleted mice: both CD4+ and CD8+ cells mediate active suppression. J Immunol. 1995;155(2):910–916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey L, Spear PG. Infections with herpes simplex viruses (1) N Engl J Med. 1986;314(11):686–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198603133141105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosmi L, Liotta F, Lazzeri E, Francalanci M, Angeli R, Mazzinghi B, Santarlasci V, Manetti R, Vanini V, Romagnani P, Maggi E, Romagnani S, Annunziato F. Human CD8+CD25+ thymocytes share phenotypic and functional features with CD4+CD25+ regulatory thymocytes. Blood. 2003;102(12):4107–4114. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow MK, Kirou KA. Regulation of CD40 ligand expression in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2001;13(5):361–369. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danese S, Sans M, Fiocchi C. The CD40/CD40L costimulatory pathway in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2004;53(7):1035–1043. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.026278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson CR. Ocular herpes simplex virus infections. Clin Dermatol. 1984;2(2):56–66. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(84)90066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Totero D, Montera M, Rosso O, Clavio M, Balleari E, Foa R, Gobbi M. Resistance to CD95-mediated apoptosis of CD40-activated chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells is not related to lack of DISC molecules expression. Hematol J. 2004;5(2):152–160. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debroy C, Pederson N, Person S. Nucleotide sequence of a herpes simplex virus type 1 gene that causes cell fusion. Virology. 1985;145(1):36–48. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90199-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhodapkar MV, Steinman RM. Antigen-bearing immature dendritic cells induce peptide-specific CD8(+) regulatory T cells in vivo in humans. Blood. 2002;100(1):174–177. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z, Issekutz TB, Downey GP, Waddell TK. L-selectin stimulation enhances functional expression of surface CXCR4 in lymphocytes: implications for cellular activation during adhesion and migration. Blood. 2003;101(11):4245–4252. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix RD. Pathogenesis of herpes simplex ocular disease. In: Tasman W, Jaeger EA, editors. Foundations of Clinical Ophthalmology. Philadelphia: 2 Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dix RD, Mills J. Acute and latent herpes simplex virus neurological disease in mice immunized with purified virus-specific glycoproteins gB or gD. J Med Virol. 1985;17(1):9–18. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890170103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doymaz MZ, Rouse BT. Herpetic stromal keratitis: an immunopathologic disease mediated by CD4+ T lymphocytes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33(7):2165–2173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etzioni A, Ochs HD. The hyper IgM syndrome--an evolving story. Pediatr Res. 2004;56(4):519–525. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000139318.65842.4A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster TP, Kousoulas KG. Genetic analysis of the role of herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein K in infectious virus production and egress. J Virol. 1999;73(10):8457–8468. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8457-8468.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasi H, Bahri S, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL. Protection against herpes simplex virus-induced eye disease after vaccination with seven individually expressed herpes simplex virus 1 glycoproteins. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995a;36(7):1352–1360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasi H, Cai S, Perng GC, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL. The role of natural killer cells in protection of mice against death and corneal scarring following ocular HSV-1 infection. Antiviral Res. 2000a;45(1):33–45. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(99)00075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasi H, Cai S, Slanina S, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL. Nonneutralizing antibody against the glycoprotein K of herpes simplex virus type-1 exacerbates herpes simplex virus type-1-induced corneal scarring in various virus-mouse strain combinations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997a;38(6):1213–1221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasi H, Kaiwar R, Nesburn AB, Slanina S, Wechsler SL. Expression of seven herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoproteins (gB, gC, gD, gE, gG, gH, and gI): comparative protection against lethal challenge in mice. J Virol. 1994a;68(4):2118–2126. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2118-2126.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasi H, Perng G, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL. Antibody-dependent enhancement of HSV-1 infection by anti-gK sera. Virus Res. 2000b;68(2):137–144. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(00)00165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasi H, Roopenian DC, Slanina S, Cai S, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL. The importance of MHC-I and MHC-II responses in vaccine efficacy against lethal herpes simplex virus type 1 challenge. Immunology. 1997b;91(3):430–435. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasi H, Slanina S, Nesburn AB, Wechsler SL. Characterization of baculovirus-expressed herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein K. J Virol. 1994b;68(4):2347–2354. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2347-2354.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasi H, Wechsler SL, Cai S, Nesburn AB, Hofman FM. The role of neutralizing antibody and T-helper subtypes in protection and pathogenesis of vaccinated mice following ocular HSV-1 challenge. Immunology. 1998;95(3):352–359. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasi H, Wechsler SL, Kaiwar R, Nesburn AB, Hofman FM. Local expression of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-2 correlates with protection against corneal scarring after ocular challenge of vaccinated mice with herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol. 1995b;69(1):334–340. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.334-340.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliet M, Liu YJ. Generation of human CD8 T regulatory cells by CD40 ligand-activated plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195(6):695–704. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks RL, Epstein RJ, Tumpey T. The effect of cellular immune tolerance to HSV-1 antigens on the immunopathology of HSV-1 keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989;30(1):105–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks RL, Janowicz M, Tumpey TM. Critical role of corneal Langerhans cells in the CD4- but not CD8- mediated immunopathology in herpes simplex virus-1-infected mouse corneas. J Immunol. 1992;148(8):2522–2529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks RL, Tumpey TM. Contribution of virus and immune factors to herpes simplex virus type I- induced corneal pathology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31(10):1929–1939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill TJ. Ocular pathogenicity of herpes simplex virus. Curr Eye Res. 1987;6(1):1–7. doi: 10.3109/02713688709020060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huster KM, Panoutsakopoulou V, Prince K, Sanchirico ME, Cantor H. T cell-dependent and -independent pathways to tissue destruction following herpes simplex virus-1 infection. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32(5):1414–1419. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200205)32:5<1414::AID-IMMU1414>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson L, Johnson DC. Herpes simplex virus glycoprotein K promotes egress of virus particles. J Virol. 1995;69(9):5401–5413. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5401-5413.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson L, Roop-Beauchamp C, Johnson DC. Herpes simplex virus glycoprotein K is known to influence fusion of infected cells, yet is not on the cell surface. J Virol. 1995;69(7):4556–4563. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4556-4563.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imadome K, Shimizu N, Yajima M, Watanabe K, Nakamura H, Takeuchi H, Fujiwara S. CD40 signaling activated by Epstein-Barr virus promotes cell survival and proliferation in gastric carcinoma-derived human epithelial cells. Microbes Infect. 2009;11(3):429–433. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabe T, Naka T, Yoshida K, Tanaka T, Fujiwara H, Suematsu S, Yoshida N, Kishimoto T, Kikutani H. The immune responses in CD40-deficient mice: impaired immunoglobulin class switching and germinal center formation. Immunity. 1994;1(3):167–178. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiniwa Y, Miyahara Y, Wang HY, Peng W, Peng G, Wheeler TM, Thompson TC, Old LJ, Wang RF. CD8+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells mediate immunosuppression in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(23):6947–6958. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlmann WM, Urban W, Sterry W, Foerster J. Correlation of psoriasis activity with abundance of CD25+CD8+ T cells: conditions for cloning T cells from psoriatic plaques. Exp Dermatol. 2004;13(10):607–612. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2004.00195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liesegang TJ. Classification of herpes simplex virus keratitis and anterior uveitis. Cornea. 1999;18(2):127–143. doi: 10.1097/00003226-199903000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liesegang TJ. Herpes simplex virus epidemiology and ocular importance. Cornea. 2001;20(1):1–13. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200101000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HH, Faunce DE, Stacey M, Terajewicz A, Nakamura T, Zhang-Hoover J, Kerley M, Mucenski ML, Gordon S, Stein-Streilein J. The macrophage F4/80 receptor is required for the induction of antigen-specific efferent regulatory T cells in peripheral tolerance. J Exp Med. 2005;201(10):1615–1625. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeoch DJ, Dalrymple MA, Davison AJ, Dolan A, Frame MC, McNab D, Perry LJ, Scott JE, Taylor P. The complete DNA sequence of the long unique region in the genome of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Gen Virol. 1988;69(Pt 7):1531–1574. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-7-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medici MA, Sciortino MT, Perri D, Amici C, Avitabile E, Ciotti M, Balestrieri E, De Smaele E, Franzoso G, Mastino A. Protection by herpes simplex virus glycoprotein D against Fas-mediated apoptosis: role of nuclear factor kappaB. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(38):36059–36067. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306198200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercadal CM, Bouley DM, DeStephano D, Rouse BT. Herpetic stromal keratitis in the reconstituted scid mouse model. J Virol. 1993;67(6):3404–3408. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3404-3408.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf JF, Kaufman HE. Herpetic stromal keratitis-evidence for cell-mediated immunopathogenesis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1976;82(6):827–834. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(76)90057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott KR, Chentoufi AA, Carpenter D, Benmohamed L, Wechsler SL, Ghiasi H. The role of a glycoprotein K (gK) CD8+ T-cell epitope of herpes simplex virus on virus replication and pathogenicity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(6):2903–2912. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott KR, Osorio Y, Brown DJ, Morishige N, Wahlert A, Jester JV, Ghiasi H. The corneas of naive mice contain both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Mol Vis. 2007a;13:1802–1812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott KR, Osorio Y, Maguen E, Nesburn AB, Wittek AE, Cai S, Chattopadhyay S, Ghiasi H. Role of anti-glycoproteins D (anti-gD) and K (anti-gK) IgGs in pathology of herpes stromal keratitis in humans. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2007b;48(5):2185–2193. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott KR, Perng GC, Osorio Y, Kousoulas KG, Ghiasi H. A Recombinant Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Expressing Two Additional Copies of gK Is More Pathogenic than Wild-Type Virus in Two Different Strains of Mice. J Virol. 2007c;81(23):12962–12972. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01442-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes JE, Monteiro CA, Cubitt CL, Lausch RN. Induction of interleukin-8 gene expression is associated with herpes simplex virus infection of human corneal keratocytes but not human corneal epithelial cells. J Virol. 1993;67(8):4777–4784. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4777-4784.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega G, Robb RJ, Shevach EM, Malek TR. The murine IL 2 receptor. I. Monoclonal antibodies that define distinct functional epitopes on activated T cells and react with activated B cells. J Immunol. 1984;133(4):1970–1975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio Y, Cai S, Hofman FM, Brown DJ, Ghiasi H. Involvement of CD8+ T cells in exacerbation of corneal scarring in mice. Curr Eye Res. 2004;29:145–151. doi: 10.1080/02713680490504632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio Y, La Point SF, Nusinowitz S, Hofman FM, Ghiasi H. CD8+-dependent CNS demyelination following ocular infection of mice with a recombinant HSV-1 expressing murine IL-2. Exp Neurol. 2005;193(1):1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio Y, Mott KR, Jabbar AM, Moreno A, Foster TP, Kousoulas KG, Ghiasi H. Epitope mapping of HSV-1 glycoprotein K (gK) reveals a T cell epitope located within the signal domain of gK. Virus Res. 2007;128(1–2):71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid DS. The human MHC-restricted cellular response to herpes simplex virus type 1 is mediated by CD4+, CD8− T cells and is restricted to the DR region of the MHC complex. J Immunol. 1988;140(10):3610–3616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamenkovic I. The L-selectin adhesion system. Curr Opin Hematol. 1995;2(1):68–75. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199502010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumpey TM, Cheng H, Cook DN, Smithies O, Oakes JE, Lausch RN. Absence of macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha prevents the development of blinding herpes stromal keratitis. J Virol. 1998a;72(5):3705–3710. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3705-3710.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tumpey TM, Cheng H, Yan XT, Oakes JE, Lausch RN. Chemokine synthesis in the HSV-1-infected cornea and its suppression by interleukin-10. J Leukoc Biol. 1998b;63(4):486–492. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.4.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usherwood EJ, Hogan RJ, Crowther G, Surman SL, Hogg TL, Altman JD, Woodland DL. Functionally heterogeneous CD8(+) T-cell memory is induced by Sendai virus infection of mice. J Virol. 1999;73(9):7278–7286. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7278-7286.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kooten C, Banchereau J. CD40-CD40 ligand. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67(1):2–17. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Yamamoto N, Maruoka H, Tamai H, Matsuzuka F, Miyauchi A, Iwatani Y. Independent involvement of CD8+ CD25+ cells and thyroid autoantibodies in disease severity of Hashimoto's disease. Thyroid. 2002;12(9):801–808. doi: 10.1089/105072502760339370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmus KR, Dawson CR, Barron BA, Bacchetti P, Gee L, Jones DB, Kaufman HE, Sugar J, Hyndiuk RA, Laibson PR, Stulting RD, Asbell PA. Risk factors for herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis recurring during treatment of stromal keratitis or iridocyclitis. Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80(11):969–972. doi: 10.1136/bjo.80.11.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xystrakis E, Dejean AS, Bernard I, Druet P, Liblau R, Gonzalez-Dunia D, Saoudi A. Identification of a novel natural regulatory CD8 T-cell subset and analysis of its mechanism of regulation. Blood. 2004;104(10):3294–3301. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao ZS, Granucci F, Yeh L, Schaffer PA, Cantor H. Molecular mimicry by herpes simplex virus-type 1: autoimmune disease after viral infection. Science. 1998;279(5355):1344–1347. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5355.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. 1. Single and double peroxide immunohistochemistry in BALB/c eye. BALB/c mice were immunized and infected as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Eyes were removed from each animal on day 5 PI and processed for presence of CD4+ (red), CD25+ (blue) and CD4+CD25+ (dark gray) by immunohistochemistry. Colorimetric differences in peroxide staining are evident to allow distinction between single-stained and double-stained cells. 60× direct visualization.

Supplementary Fig. 2. MHC-1 and MHC-II peroxide immunohistochemistry in BALB/c cornea. BALB/c mice were immunized and infected as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Eyes were removed from each animal on day 5 PI and processed for presence of MHC-I and MHC-II by immunohistochemistry. 60× direct visualization of cornea.

Supplementary Fig. 3. Splenic infiltrates following HSV-1 ocular infection of immunized mice. BALB/c mice were immunized and infected as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Spleens were harvested on day 5 PI, snap frozen, and processed as described in Materials and Methods. Representative spleen sections were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD25, anti-B7-1, anti-B7-2, anti-CD19, anti-CD40, anti-CD40L, anti-CD62L, anti-CD95, anti-MHC-I, or anti-MHC-II mAb. 60× direct magnification.

Supplementary Fig. 4. Thymic infiltrates following HSV-1 ocular infection of immunized mice. BALB/c mice were immunized and infected as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Thymuses were harvested on day 5 PI, snap frozen, and processed as described in Materials and Methods. Representative spleen sections were stained with anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD25, anti-B7-1, anti-B7-2, anti-CD19, anti-CD40, anti-CD40L, anti-CD62L, anti-CD95, anti-MHC-I, or anti-MHC-II mAb. 60× direct magnification.

Supplementary Fig. 5. Expression of CD4, CD8, CD25, CD40, CD40L, FoxP3 and active Caspase-3 transcripts in spleen of immunized and infected mice. BALB/c mice were immunized and infected as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Spleens were removed from each animal on days 5, 10, 14 and 28 post-infection were processed for RNA extraction. CD4, CD8, CD25, CD40, CD40L, Active Caspase-3 and FoxP3 expression in naive mice was used to estimate the relative expression of each transcript in corneas of mice in gK-, gD-, or mock- immunized groups. GAPDH expression was used to normalize the relative expression of each transcript in spleen of gK-, gD-, or mock-immunized mice. Each point represents the mean ± SEM from 3 mice. Panels: A) CD4 transcript; B) CD8 transcript; C) FoxP3 transcript; D) CD25 transcript; E) CD40 transcript; F) CD40L transcript and G) Active Caspase-3 transcript. *, **, *** significantly different at P<0.05, P<0.01, and P<0.001, respectively.