Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the ability of the GDx VCC Guided Progression Analysis software (GDx-GPA) for detecting glaucomatous progression.

Design

Observational cohort study.

Participants

The study included 453 eyes from 252 individuals followed for an average of 46 ± 14 months as part of the Diagnostic Innovations in Glaucoma Study (DIGS). At baseline, 29% of the eyes were classified as glaucomatous, 67% were classified as suspects and 5% as healthy eyes.

Methods

Images were obtained annually with the GDx VCC and analyzed for progression using the Fast Mode of the GDx-GPA software. Progression using conventional methods was determined by the Guided Progression Analysis software for SAP and by masked assessment of optic disc stereophotographs by expert graders.

Main Outcome Measures

Sensitivity, specificity and likelihood ratios (LR) for detection of glaucoma progression using the GDx GPA were calculated with SAP and optic disc stereophotographs used as reference standards. Agreement among the different methods was reported using the AC1 coefficient.

Results

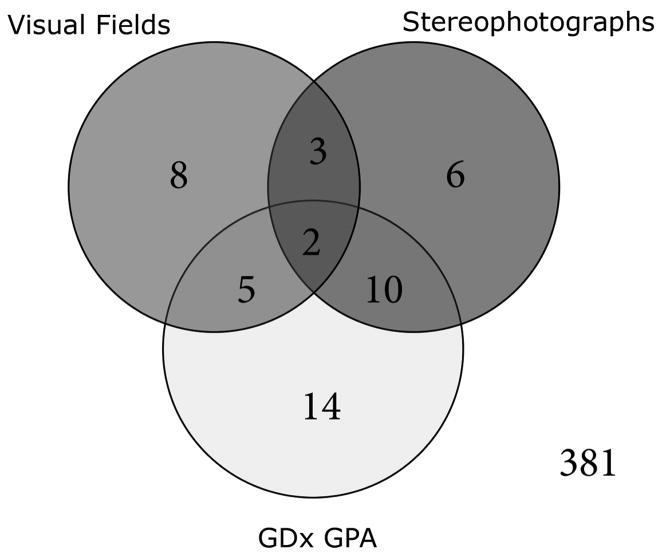

Thirty-four of the 431 (8%) glaucoma and glaucoma suspect eyes showed progression by SAP and/or optic disc stereophotographs. The GDx-GPA detected 17 of these eyes for a sensitivity of 50%. Fourteen eyes showed progression only by the GDx-GPA with specificity of 96%. Positive and negative LRs were 12.5 and 0.5, respectively.

None of the healthy eyes showed progression by the GDx-GPA, with a specificity of 100% in this group. Inter-method agreement (AC1 coefficient and 95% confidence intervals) for non-progressing and progressing eyes was 0.96 (0.94–0.97) and 0.44 (0.28–0.61), respectively.

Conclusion

The GDx-GPA was able to detect glaucoma progression in a significant number of cases showing progression by conventional methods, with high specificity and high positive likelihood ratios. Estimates of the accuracy for detecting progression suggest that the GDx-GPA could be used to complement clinical evaluation in the detection of longitudinal change in glaucoma.

Introduction

Accurate methods for detecting glaucoma progression are essential in order to monitor patients and evaluate the efficacy of therapy. Although standard automated achromatic perimetry (SAP) has been the most commonly used method to assess progression, several studies have shown that deterioration of the optic nerve head (ONH) and retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) may often precede visual field loss detected by perimetry.1–4 In fact, changes in the RNFL have been reported to be the earliest and even the only sign of glaucoma development and progression in many patients. 3, 5, 6

Clinical examination at the slit lamp or by red-free photographs offers suboptimal evaluation of the RNFL that is dependent on subjective assessment and is impaired in eyes with lightly pigmented fundus, small pupils or media opacities. Optical imaging instruments have added quantitative and objective information to the RNFL examination. Compared to subjective assessment, automated analysis potentially increases the ability to detect deviations from normality and change over time.

Scanning Laser Polarimetry (SLP) was developed with the purpose of evaluating the thickness of the RNFL. SLP measurements have been shown to discriminate glaucomatous from normal eyes and to predict development of visual field loss in patients suspected of having glaucoma.7–9 In a previous longitudinal study, we showed that rates of RNFL loss as measured by SLP were significantly higher in patients showing progression by visual fields and/or optic disc photographs compared to patients who remained stable.10 Although that study provides evidence of the ability of this technology to detect glaucomatous progression, there is a need to evaluate methods for detecting progression with SLP that can be directly applied in clinical practice to individual patients. The commercially available GDx VCC scanning laser polarimeter (Carl-Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA) has been recently upgraded with the addition of a Guided Progression Analysis (GPA). The GPA software evaluates and compares SLP images acquired during follow-up and reports a summary analysis for progression in an individual eye after automated consideration of expected test-retest variability.

In order for a new method to gain acceptance into clinical practice, it is important to evaluate and compare it to accepted reference standards. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the ability of the GDx GPA software to detect progression in a cohort of glaucoma patients and patients suspected of having the disease followed over time and to compare it with SAP and optic disc stereophotographs.

Methods

This was an observational cohort study. Patients were selected from a prospective longitudinal study designed to evaluate optic nerve structure and visual function in glaucoma (DIGS – Diagnostic Innovations in Glaucoma Study) conducted at the Hamilton Glaucoma Center, University of California, San Diego (UCSD). All patients from the DIGS who met the inclusion criteria described below were enrolled. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, the UCSD Human Subjects Committee approved all protocols, and the methods described adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Each subject underwent a comprehensive ophthalmologic examination including review of medical history, best-corrected visual acuity, slit-lamp biomicroscopy, intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement, gonioscopy, dilated fundoscopic examination, stereoscopic optic disc photography, and automated perimetry using either 24-2 Full-threshold, or Swedish Interactive Threshold Algorithm (SITA). Only subjects with open angles on gonioscopy were included. Subjects were excluded if they presented best-corrected visual acuity less than 20/40, spherical refraction outside ± 5.0 diopters and/or cylinder correction outside 3.0 diopters; or any other ocular or systemic disease that could affect the optic nerve or the visual field.

We included 453 eyes from 252 individuals. Subjects were selected based on the minimum number of GDx exams for running the guided progression analysis software (see below). At baseline, 129 (29%) eyes had repeatable abnormal visual fields and were classified as glaucomatous; 302 (67%) were classified as glaucoma suspects and 22 (5%) were healthy eyes. Abnormal visual fields were defined as a pattern standard deviation (PSD) with P < .05 and/or a Glaucoma Hemifield Test (GHT) “Outside Normal Limits.” Glaucoma suspects had suspicious optic disc appearance (as determined by subjective assessment on the baseline visit) and/or elevated intraocular pressure (IOP > 21 mmHg), but normal and reliable standard automated perimetry (SAP) visual fields at baseline. Normal individuals were recruited from the general population through advertisement, as well as from the staff and employees of the University of California, San Diego. Normal control eyes had normal findings in clinical examination, IOP of 21 mmHg or less with no history of increased IOP, normal appearance of the optic nerve and a normal visual field result. During follow-up time, each patient was treated at the discretion of the attending ophthalmologist.

Standard Automated Perimetry

Standard automated perimetry (SAP) visual fields were obtained using either 24-2 Full Threshold or Swedish Interactive Thresholding Algorithm – SITA (Humphrey Field Analyzer - HFA, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA) strategies. Only reliable tests (≤ 33% fixation losses and false negatives, and < 15% false positives) were included. Glaucomatous progression by visual field was evaluated using the HFA Guided Progression Analysis (SAP GPA). Progression by SAP GPA was defined as a significant decrease from baseline (two exams) pattern deviation at three or more of the same test points on three consecutive tests, which is classified by the software as Likely Progression. All cases of progression were evaluated by a masked glaucoma specialist to determine if the changes detected were characteristic of glaucomatous visual field progression. Among the 18 cases detected as progressing by visual fields, none was discarded as artifacts or with non-glaucomatous progression.

Stereophotograph grading

Simultaneous stereoscopic color optic disc photographs (TRC-SS; Topcon Instrument Corp of America, Paramus, New Jersey) were reviewed using a stereoscopic viewer (Asahi Pentax Stereo Viewer II; Asahi Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan). For progression assessment, each patient’s most recent stereophotograph was compared to the baseline one. Only photographs with adequate quality and clarity were included. Definition of change was based on focal or diffuse thinning of the neuroretinal rim, increased excavation, and detection of new or enlarged RNFL defects. Isolated optic disc hemorrhages and progressive peripapillary atrophy were not considered progression. All graders were masked to identification and temporal sequence of the photographs. Discrepancies between the two graders were resolved by adjudication of a third experienced grader.

Scanning Laser Polarimetry

All patients were imaged using the commercially available scanning laser polarimeter GDx with Variable Corneal Compensation (VCC) (software version 5.0, Carl-Zeiss Meditec Inc., Dublin, CA), and analyzed with the GDx Guided Progression Analysis (GPA) algorithm (software version 6.0). Eligible subjects were included if they presented a minimum of 4 GDx tests and at least one year of follow-up. Only well focused, evenly illuminated, centered GDx VCC scans with SD ≤ 7 μm and Typical Scan Score (TSS) of > 40 were included. For the progression analysis, one image per eye was selected as the reference image, to which all others were aligned. No images were included on the progression analysis with alignment registration scores < 50. To allow progression to be detected by each method during the same period of follow-up, the second baseline GDx VCC image was matched (within one year) to the second baseline for SAP GPA and the baseline date of stereophotographs.

The GDx GPA software can run in two different modes, the Fast Mode and the Extended Mode. The Fast Mode needs one single image for each visit, while the Extended Mode requires three images for each visit. In the Fast Mode, detection of change is based on comparison to predetermined threshold levels of variability derived from a sample population, and available in the software’s normative database. In contrast, in the Extended Mode the software calculates the test-retest variability of the specific eye being tested based on the observed variability among the three images of each visit. In the current study, we only report results for the Fast Mode.

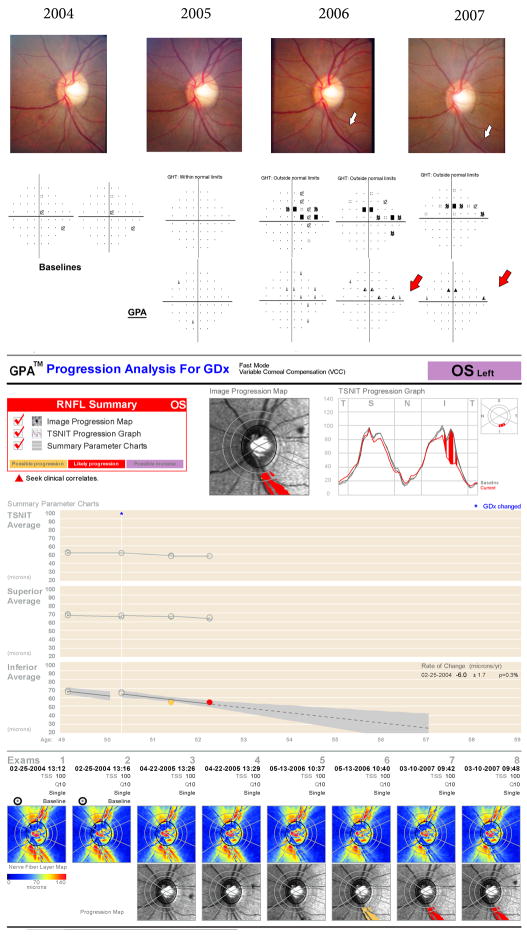

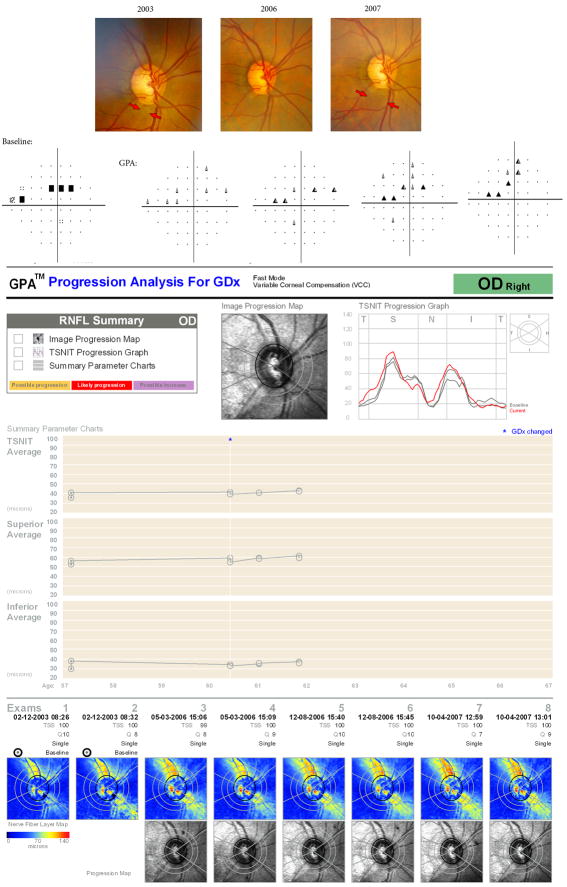

Using the Fast Mode, the GDx GPA defines significant change if the follow-up image is different from both baseline images and the amount of difference is larger than the expected variability. Results are displayed in the Summary Box as Possible Progression if significant decrease in RNFL thickness is detected once, Likely Progression if significant reduction is detected in at least two consecutive exams, and Possible Increase if an increase in RNFL thickness is detected. Results are provided in three different maps, each focusing on a specific pattern of damage (Figure 1 and 2). 1) The Image Progression Map represents a fundus image with color-coded areas. Significant change in clusters of ≥ 150 adjacent pixels is flagged as progression. This map was designed to be more sensitive to narrow, focal RNFL loss. 2) The TSNIT Progression Graph shows RNFL thickness measurements around the optic disc. Significant change in ≥ 4 adjacent segments from the calculation circle is flagged as progression. It was designed to be most sensitive to broader focal changes in the RNFL. 3) The Summary Parameters Charts represents the parameters TSNIT average (average of RNFL thickness measurements obtained on a 3.2 mm diameter calculation circle around the optic nerve head; T accounts for temporal, S, for superior, N, for nasal, and I, for inferior), the Superior Average, and the Inferior Average plotted over time. If progression is detected with a significant linear trend (P < 5%), the correspondent rate of change (given in μm/year) is also provided. It was designed to be more sensitive to diffuse change.

Figure 1.

Example of a 48 year-old African-American patient suspected of having glaucoma based on high levels of intraocular pressure at the baseline. The optic disc at the baseline shows a slightly tilted disc with a normal appearance of the neuroretinal rim and a normal pattern of brightness and striations of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL). During the follow-up, a new localized RNFL defect can be observed in the inferior temporal sector on the optic disc stereophotographs and the visual fields show a corresponding superior defect. All three maps of the GDx Guided Progression Analysis (GPA) report were able to detect RNFL loss in the same sector, in agreement with both conventional methods.

Figure 2.

Example of a 56 year-old Caucasian male diagnosed with glaucoma and followed for almost 5 years under treatment. The figure shows an example of disagreement among methods for detection of change. The optic disc stereophotographs showed progressive retinal nerve fiber layer loss in the inferior temporal sector, with corresponding visual field loss. Even though the GDx shows pronounced the retinal nerve fiber layer damage at the corresponding position, the GDx Guided Progression Analysis (GPA) software was not able to identify significant worsening over time.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics included mean and standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed variables and median, first quartile, and third quartile values for non-normally distributed variables. Student’s t tests or Mann Whitney U tests were used to evaluate demographic and clinical differences between progressing and non-progressing eyes.

Sensitivities, specificities, positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV), and likelihood ratios (LR) were obtained assuming optic disc stereophotographs and visual fields as reference standards for detection of change (see discussion). The Kappa statistic (κ) and the AC1-statistic (Gwet’s Agreement Coefficient)11 were used to quantify and evaluate the agreement for detection of progression among the different methods. A well known limitation of the kappa statistic to determine agreement is that it is highly dependent on the prevalence of a trait (in our study, the prevalence of progression). Kappa estimates may suggest very low agreement when the prevalence is either too low or too high in the population of the study.12 Given the expected low positive rate for progression in our study, we also reported AC1-statistics, which has the potential benefit of taking into account the effect of prevalence, being more consistent with the overall percentage of agreement between two methods. The AC1 also provides more stable results in situations with variable prevalence of the event of interest compared to kappa.13

Where agreement existed, congruity between GDx GPA, stereophotographs and visual field sectors was assessed by comparing hemifields. Statistical analyses were performed using software SPSS 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). The alpha level (type I error) was set at 0.05. 95% confidence intervals for the AC1 agreement were calculated using bootstrap statistics for the overall group and for each individual category.

Results

Four-hundred and fifty-three eyes from 252 individuals were included, with a mean ± SD age of 61 ± 13 years. One-hundred forty-two (57%) patients were female. There were 163 (65%) Caucasians, 71 (28%) African-Americans, 8 (3%) Asians, and 10 (4%) Hispanics. Median overall follow-up time was 48 months (first quartile 35 months, third quartile 58 months). Table 1 shows baseline demographic and clinical characteristics based on the classification at entry on the study.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics, based on the classification at the baseline, for the 453 eyes from 252 individuals included in the study.

| Healthy (22 eyes) |

Suspects (302 eyes) |

Glaucomatous (129 eyes) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Progressors | 0 (0%) | 19 (6%) | 15 (12%) |

| Follow-up (months) | 46.1 (12.0) | 46.6 (13.8) | 45.9 (14.1) |

| Age at baseline (years) | 57.0 (16.0) | 59.6 (12.6) | 63.1 (11.5) |

| Baseline GDx: | |||

| NFI | 20.3 (6.4) | 24.2 (12.3) | 41.2 (21.0) |

| TSNIT Average (μm) | 52.7 (5.5) | 51.6 (6.2) | 46.7 (7.9) |

| Superior Average (μm) | 63.5 (6.9) | 61.7 (9.1) | 53.9 (12.0) |

| Inferior Average (μm) | 62.5 (8.0) | 59.8 (8.5) | 53.8 (10.5) |

| TSNIT Std. Deviation (μm) | 23.3 (4.0) | 20.8 (4.7) | 18.4 (5.4) |

| Baseline Visual Field: | |||

| MD median (dB) | −0.43 | −0.74 | −3.88 |

| (first/last quartiles) | (−1.21, −0.01) | (−1.62, 0.12) | (−5.96, −2.26) |

| PSD median (dB) | 1.50 | 1.56 | 3.52 |

| (first/last quartiles) | (1.37, 1.67) | (1.37, 1.79) | (2.46, 6.76) |

| Baseline stereophotograph: | |||

| Glaucomatous optic neuropathy n (%) | 0 | 135 (45%) | 85 (66%) |

| CDR | 0.53 (0.14) | 0.59 (0.17) | 0.69 (0.19) |

MD, mean deviation; PSD, pattern standard deviation; NFI, Nerve fiber indicator; TSNIT, temporal superior nasal inferior temporal; CDR, cup-to-disc ratio.

During follow-up, 34 eyes (8%) from 32 patients showed progression by conventional methods. Among these 34 progressing eyes, 13 (38%) showed progression based only on visual field loss, 16 (47%) based only on optic disc changes, and 5 (15%) based on both optic disc and visual field changes. Median (first quartile, third quartile) follow-up times for progressing and non-progressing eyes were 57 months (42 months, 59 months) and 47 months (35 months, 57 months), respectively. At the baseline visit, 15 (44%) of the 34 progressing eyes were classified as glaucoma suspects, whereas 19 (56%) were already glaucomatous.

The GDx GPA software detected 17 of the 34 eyes that progressed by optic disc stereophotographs and/or visual fields, with an overall sensitivity of 50% and positive predictive value (PPV) of 52%. The positive likelihood ratio was 12.5. The GDx GPA detected 12 (57%) of the 21 eyes that progressed by optic disc stereophotographs and 7 (39%) of the 18 eyes that progressed by SAP. When all 431 glaucoma and glaucoma suspect eyes were considered, 14 eyes showed progression by the GDx GPA but not by SAP and/or optic disc stereophotographs with specificity of 96% and negative predictive value (NPV) of 96%. The negative likelihood ratio was 0.5.

We also evaluated the specificity of the GDx GPA in the group of 22 healthy eyes (19 subjects) that were followed for an average of 46.1 ± 12 months. These eyes had normal optic disc appearance and normal visual fields at baseline and did not show progression by SAP or stereophotographs over time. None of the healthy eyes showed progression in any of the GDx GPA progression maps with a specificity of 100%.

Complete agreement between GDx GPA and conventional methods was observed in 400 (93%) of 431 glaucoma and glaucoma suspect eyes (Figure 3). However, the percentage of agreement among those for which at least one method detected progression (effective percentage of agreement) was 35%. Kappa between conventional methods and GDx GPA was 0.48 (95% CI: 0.33 to 0.64; P < 0.001). The agreement coefficient AC1 was 0.92 (95% CI: 0.89 to 0.95, P < 0.001). Inter-method agreement for non-progressing and progressing eyes was 0.96 (95% CI: 0.94 to 0.97) and 0.44 (95% CI: 0.28 to 0.61), respectively. Table 2 shows baseline clinical characteristics of the eyes detected as progressing only by the GDx GPA and those detected only by conventional methods. Eyes that were detected as progressing only by stereophotographs and/or visual fields had significantly worse disease at baseline compared to eyes progressing only by the GDx GPA software, as indicated by worse visual field indexes, higher cup/disc ratios and lower RNFL thickness measurements.

Figure 3.

Venn diagram showing the number of exams classified as progressing by the GDx Guided Progression Analysis (GPA), standard achromatic perimetry GPA and expert clinician stereophotographs assessment.

Table 2.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, stratified by the method that detected progression. Unless otherwise specified results are given as mean (standard deviation).

| Progression only by conventional methods (n = 17) |

Progression only by the GDx (n = 14) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up (months) | 52.5 (12.0) | 42.7 (14.7) | 0.088 |

| Age at baseline (years) | 67.1 (9.0) | 57.9 (12.6) | 0.053 |

| Baseline GDx: | |||

| NFI | 47.3 (21.4) | 19.5 (13.3) | 0.001 |

| TSNIT Average (μm) | 43.4 (6.7) | 53.4 (6.8) | 0.001 |

| Superior Average (μm) | 50.1 (10.3) | 66.6 (10.3) | 0.001 |

| Inferior Average (μm) | 48.6 (11.1) | 61.0 (8.4) | 0.002 |

| TSNIT Std. Deviation (μm) | 16.4 (5.3) | 24.7 (4.6) | < 0.001 |

| Baseline Visual Field: | |||

| MD mean (dB) | −4.26 (4.26) | −1.42 (2.03) | 0.123 |

| PSD mean (dB) | 4.31 (3.38) | 2.50 (1.43) | 0.154 |

| Baseline stereophotograph: | |||

| Glaucomatous optic neuropathy n (%) | 16 (84%) | 3 (21%) | < 0.001 |

| CDR | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.1) | < 0.001 |

MD, mean deviation; PSD, pattern standard deviation; NFI, Nerve Fiber Indicator; TSNIT, Temporal Superior Nasal Inferior Temporal; CDR, cup-to-disc ratio.

Among the 31 eyes that showed progression with the GDx GPA, there were 20 (65%) with progression detected on the Image Progression Map, 23 (74%) with progression detected on the TSNIT Progression Map and 20 (65%) with progression detected on the Summary Parameters Chart. Sixteen (52%) of the 31 eyes had progression detected by more than one map. Of the 12 eyes with progression detected by both stereophotographs and GDx GPA, there was congruity in at least one hemifield in 11 (92%). Of the 7 individuals with progression detected by both visual fields and GDx GPA, congruity in at least one hemifield was found in 5 (71%). Figure 1 shows an example of an eye where there was complete agreement among all methods for detection of progression. The eye developed a progressive inferior localized RNFL defect as seen on the optic disc stereophotographs with corresponding superior visual field loss. The GDx GPA software showed progression in the inferior temporal sector in all three progression maps. Figure 2 shows an example of disagreement among methods for detection of change. The optic disc stereophotographs showed progressive retinal nerve fiber layer loss in the inferior temporal sector with corresponding visual field loss. Even though the GDx retardation map shows pronounced RNFL damage at the corresponding position both at the baseline and on follow-up exams, the GDx GPA software was not able to identify significant worsening over time.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to provide a comparison, within the same population, of the ability of the GDx GPA, SAP and optic disc stereophotographs for detection of glaucomatous progression. The GDx GPA software was able to identify a significant proportion of glaucoma and glaucoma suspect eyes that showed progression by optic disc stereophotographs and visual fields, with high specificity. Although the agreement with conventional methods was less than perfect, estimates of PPV, NPV and likelihood ratios show that the GDx GPA may be used as an additional tool for longitudinal monitoring of glaucoma eyes and eyes suspected of having disease.

In our cohort of 431 glaucoma and glaucoma suspect eyes followed over time, GDx GPA and conventional methods agreed in 93% of the eyes. However, the high level of agreement was mostly due to concordance in non-progressing cases. Although the number of eyes detected as progressing was relatively similar with each method (31 (7%) eyes with the GDx GPA, 18 (4%) with SAP, and 21 (5%) with stereophotographs), these were not always the same eyes. Similar disagreements have been observed in studies comparing other imaging technologies with visual fields and optic disc sterephotographs.14–18 In a longitudinal study of 64 eyes followed for an average of 4.7 years, Wollstein et al.18 found that 22% of the eyes progressed by optical coherence tomography (OCT) alone, whereas 9% progressed by visual fields alone and only 3% progressed by both methods. Using confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (CSLO), Chauhan et al.17 reported results on 77 early glaucomatous eyes followed for 5.5 years. Thirty-one patients (40%) progressed with scanning laser tomography only, 3 (4%) progressed with conventional perimetry only and 22 patients (29%) progressed with both techniques. Similar disagreements were found in other studies using CSLO by Bowd et al.16 and Strouthidis et al.15.

Although the GDx GPA was able to identify only 50% of the eyes progressing by visual fields and stereophotographs, the test had very high specificity of 96%. When analyzing diagnostic accuracy, it is important to keep in mind the existing tradeoff between sensitivity and specificity. Selection of different cutoffs could have increased the sensitivity while decreasing specificity. This is important when comparing results from different technologies. For example, although a previous report by Bowd et al.16 reported a sensitivity of 80% for CSLO in detecting progression, the specificity of this technology for detecting change in glaucoma and glaucoma suspects using optic disc photos and visual fields as reference standards was much lower, around 50%.

Evidence-Based medicine guidelines have suggested that likelihood ratios are the best way to judge by how much a test result can help in clinical practice.19, 20 The GDx GPA had a large positive likelihood ratio of 12.5. The likelihood ratio for a given test result indicates how much that result will raise or lower the probability of a condition, which in our application refers to presence of glaucoma progression. It represents the magnitude of change from a clinician’s initial suspicion for a condition (pre-test probability) to the likelihood of the condition being present after the test result (post-test probability). A value of 1 means that the test provides no additional information and ratios above or below 1 respectively increase or decrease the likelihood. According to the same guidelines, LRs greater than 10 or lower than 0.1 are associated with large effects on post-test probability, LRs from 5 to 10 or from 0.1 to 0.2 are associated with moderate effects, LRs from 2 to 5 or from 0.2 to 0.5 are associated with small effects, whereas LRs closer to 1 are insignificant. Therefore, the large positive likelihood ratio for GDx GPA indicates that an eye that is detected as progressing by this method will have a large increase in the chance of having true glaucoma progression. Therefore, when used as a complement to the clinical evaluation, results of the GDx GPA may help clinicians decide whether an eye is showing disease deterioration. On the other hand, the negative likelihood ratio of the GDx GPA was 0.5. This indicates that a negative result on the GDx GPA (i.e., absence of progression) would induce only a small change in the probability of progression and could not be used to completely discard the possibility that the eye is truly deteriorating. Likelihood ratios for detection of glaucoma progression can also be calculated for other imaging instruments using previous publications that have also used visual fields and/or optic disc stereophotographs as reference standards. For OCT, results from Wollstein et al.18 would indicate positive and negative likelihood ratios of only 1. For CSLO, the report from Bowd et al.16 would indicate positive LRs ranging from 1.4 to 1.5 and negative LRs ranging from 0.5 to 0.6, depending on the method used to determine progression. Similar LRs can be derived for CSLO from the work by Chauhan et al.,17 with positive LR of 1.5 and negative LR of 0.3. These likelihood ratios for OCT and CSLO would be considered to have minimal impact in changing the probability of progression.

It is important to emphasize that calculations of likelihood ratios as performed above depend on the accuracy of visual fields and stereophotographs when used as reference methods to detect progression. Although widely accepted in clinical practice, the use of SAP and optic disc stereophotographs as reference standards may be subject to criticism. Visual fields and stereophotographs are imperfect reference standards and it is possible that some of the eyes that were detected as changing by the GDx GPA but not by conventional methods would in fact be true progressors. This would underestimate the specificity of the GDx GPA in the cohort of glaucoma and glaucoma suspect eyes. Therefore, we also evaluated the specificity of the GDx GPA in a group of healthy eyes with a similar follow-up time. The specificity in this group was even higher (100%), suggesting the possibility that the GDx GPA could in fact be detecting change not apparent on conventional methods. In fact, earlier studies using red-free photographs suggested that changes in the RNFL may be the earliest and even the only sign of glaucoma development and progression in many patients.3, 5, 21 Previous studies using other imaging instruments have also found higher specificities when estimated from healthy eyes followed over time.16, 17 Estimates of LRs for these devices are also better if specificities obtained from healthy eyes are used. However, calculations of specificity for detection of glaucoma progression using completely healthy eyes are not without problems. In clinical practice, imaging instruments are applied to detect and monitor disease in diseased eyes or eyes suspected of having glaucoma. By definition, healthy eyes have different characteristics from the eyes followed in clinical practice and, therefore, estimates of specificity obtained from healthy eyes do not necessarily apply to the clinically relevant population. In fact, there is evidence that fluctuation on intraocular pressure levels over time may significantly affect structural measurements obtained by imaging instruments, which could affect their variability and accuracy for detection of change.22–24 Such fluctuations in intraocular pressure are less likely to occur in healthy eyes compared to glaucoma eyes or eyes suspected of having the disease. Also, long-term variability of imaging instruments is likely to be influenced by long-term changes in media opacities or development of other concomitant conditions, which will be less likely to occur in completely healthy eyes compared to disease eyes.25 Further studies are necessary to evaluate the impact of these conditions on the variability of imaging instruments over time.

Several reasons may explain the disagreement among the GDx GPA, visual fields and stereophotographs in some cases of progression. Eyes that progressed only by visual fields and stereophotographs had more severe disease at baseline than those progressing only by the GDx GPA. This is in agreement with the study by Medeiros et al.,10 showing that eyes with lower values of baseline GDx VCC measurements had less change detected by this instrument. Apparently, the GDx VCC would be more sensitive to detect progression during early stages of the disease. In fact, we observed that some of the cases in which progression was not detected by the GDx GPA had deterioration in areas for which the RNFL thickness measurements provided by the GDx VCC were already too low (below 20 μm) (Figure 2). This could represent a floor effect for detection of RNFL loss with this instrument. Alternatively, it could reflect the natural history of progression in glaucoma, with greater detectable rates of RNFL loss in the earlier stages of disease.26 Another factor that may have affected the ability of the GDx GPA to detect progression was the presence of atypical retardation patterns (ARPs) in some of the scans. ARPs are known to adversely affect the accuracy of the GDx VCC for detection of glaucoma progression.27 Recently, a new software-based algorithm called enhanced corneal compensation (ECC) has been developed to improve neutralization of ARPs and to increase the dynamic range of the measurements in the low signal range.28 Longitudinal studies have found higher rates of RNFL change with the GDx ECC compared to VCC in glaucoma patients showing progression.10, 29 Therefore, it is possible that the GDx GPA software for ECC will significantly outperform the VCC for detection of progression, especially in cases with ARPs or with more severe disease, but further studies are necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

Our study has limitations. The incidence of progression during follow-up was relatively low, which may have limited the precision of the estimates of agreement among the different methods. However, as glaucoma is generally a slowly progressing disease, this is a common limitation of longitudinal studies that enroll patients under treatment. Another limitation of our study was the relatively short follow-up time with the GDx GPA, which was in average 4 years. If the GDx GPA is in fact detecting progression at the nerve fiber layer level before clinical stereophotograph assessment and/or visual fields, an increase in the follow-up would increase the number of eyes progressing with conventional methods and a better agreement would be observed. Moreover, it should be emphasized that the present protocol used for stereophotographs assessment included evaluation by trained observed from an Optic Disc Reading Center, which may represent the best achievable standards for clinical examination of the optic disc and may not hold true for general practitioners. Another limitation of our study is that some of our patients were imaged on different GDx VCC machines during follow-up. The GDx GPA software automatically recognizes if images were obtained on different devices during follow-up and uses widened limits of expected long-term variability in this situation. This could have reduced the ability of the software to detect small RNFL changes in patients who were imaged on different machines during follow-up and decreased the overall sensitivity of the method in our study. Similarly, in the current study we were only able to evaluate the accuracy of the Fast Mode of the GDx GPA for detection of progression. The Fast Mode does not take into account individual estimates of variability and rather uses predetermined cutoffs of variability from a normative population. The Extended Mode of the GDx GPA, on the other hand, calculates intra-eye estimates of variability based on multiples images obtained during the same session. It is possible that the use of the Extended Mode will improve detection of glaucoma progression with the GDx GPA.

In conclusion, the GDx GPA was able to detect glaucoma progression in a significant number of cases showing progression by stereophotographs and/or visual fields, with very high specificity. Estimates of the accuracy for detecting progression suggest that the GDx GPA could be used as a complement to the clinical evaluation in order to detect longitudinal damage in glaucoma eyes and eyes suspected of having the disease.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Supported in part by NEI EY08208 (PAS), NEI EY11008 (LMZ), Participant retention incentive grants in the form of glaucoma medication at no cost (Alcon Laboratories Inc., Allergan, Pfizer Inc., SANTEN Inc.).

Footnotes

Document type: AAO Meeting Presentation – Presented as a Poster (PO124) at the 2008 AAO Joint Meeting, Atlanta, GA.

Conflict of interest: Authors with financial conflicting interests are listed after references.

Disclosure: LM Alencar, none; C. Bowd, none; G. Vizzeri, none; RN Weinreb, Heidelberg Engineering (F, R), Carl Zeiss (F, R); LM Zangwill, Heidelberg Engineering (F), Carl Zeiss (F); PA Sample, Carl Zeiss (F), Heidelberg Engineering (F); FA Medeiros, Carl Zeiss (F, R), Heidelberg Engineering (R).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, et al. Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study Group. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:701–13. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.701. discussion 829–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon MO, Beiser JA, Brandt JD, et al. Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study Group. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: baseline factors that predict the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:714–20. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.714. discussion 829–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuulonen A, Airaksinen PJ. Initial glaucomatous optic disk and retinal nerve fiber layer abnormalities and their progression. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;111:485–90. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Glaucoma Prevention Study (EGPS) Group. Results of the European Glaucoma Prevention Study. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:366–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sommer A, Katz J, Quigley HA, et al. Clinically detectable nerve fiber atrophy precedes the onset of glaucomatous field loss. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:77–83. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080010079037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin SC, Singh K, Jampel HD, et al. Ophthalmic Technology Assessment Committee Glaucoma Panel. Optic nerve head and retinal nerve fiber layer analysis: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1937–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinreb RN, Bowd C, Zangwill LM. Glaucoma detection using scanning laser polarimetry with variable corneal polarization compensation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:218–24. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medeiros FA, Zangwill LM, Bowd C, Weinreb RN. Comparison of the GDx VCC scanning laser polarimeter, HRT II confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope, and Stratus OCT optical coherence tomograph for the detection of glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:827–37. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.6.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohammadi K, Bowd C, Weinreb RN, et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measurements with scanning laser polarimetry predict glaucomatous visual field loss. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:592–601. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medeiros FA, Alencar LM, Zangwill LM, et al. Detection of progressive retinal nerve fiber layer loss in glaucoma using scanning laser polarimetry with variable corneal compensation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:1675–81. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gwet KL. Computing inter-rater reliability and its variance in the presence of high agreement. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2008;61:29–48. doi: 10.1348/000711006X126600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gwet KL. Handbook of Inter-Rater Reliability. Gaithersburg, MD: STATAXIS Publ. Co; 2001. [Accessed July 30, 2009]. pp. 76–92. Available at: http://www.stataxis.com/3chapters_handbook.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gwet KL. Kappa statistic is not satisfactory for assessing the extent of agreement between raters. [Accessed July 30, 2009];Statistical Methods for Inter-Rater Reliability Assessment Series. 2002 1:1–6. Available at: http://www.stataxis.com/files/articles/kappa_statistic_is_not_satisfactory.pdf.

- 14.Kourkoutas D, Buys YM, Flanagan JG, et al. Comparison of glaucoma progression evaluated with Heidelberg retina tomograph II versus optic nerve head stereophotographs. Can J Ophthalmol. 2007;42:82–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strouthidis NG, Scott A, Peter NM, Garway-Heath DF. Optic disc and visual field progression in ocular hypertensive subjects: detection rates, specificity, and agreement. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2904–10. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowd C, Balasubramanian M, Weinreb RN, et al. Performance of confocal scanning laser tomograph topographic change analysis (TCA) for assessing glaucomatous progression. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:691–701. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chauhan BC, McCormick TA, Nicolela MT, LeBlanc RP. Optic disc and visual field changes in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with glaucoma: comparison of scanning laser tomography with conventional perimetry and optic disc photography. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1492–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.10.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wollstein G, Schuman JS, Price LL, et al. Optical coherence tomography longitudinal evaluation of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:464–70. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.4.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radack KL, Rouan G, Hedges J. The likelihood ratio: an improved measure for reporting and evaluating diagnostic test results. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110:689–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH, Sackett DL Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Users’ guides to the medical literature: III. How to use an article about a diagnostic test. B. What are the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? JAMA. 1994;271:703–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.9.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quigley HA, Katz J, Derick RJ, et al. An evaluation of optic disc and nerve fiber layer examinations in monitoring progression of early glaucoma damage. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:19–28. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)32018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Topouzis F, Peng F, Kotas-Neumann R, et al. Longitudinal changes in optic disc topography of adult patients after trabeculectomy. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1147–51. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90248-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshikawa K, Inoue Y. Changes in optic disc parameters after intraocular pressure reduction in adult glaucoma patients. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1999;43:225–31. doi: 10.1016/s0021-5155(99)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowd C, Weinreb RN, Lee B, et al. Optic disk topography after medical treatment to reduce intraocular pressure. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:280–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00488-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeLeon Ortega JE, Sakata LM, Kakati B, et al. Effect of glaucomatous damage on repeatability of confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope, scanning laser polarimetry, and optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1156–63. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hood DC, Anderson SC, Wall M, Kardon RH. Structure versus function in glaucoma: an application of a linear model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3662–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medeiros FA, Alencar LM, Zangwill LM, et al. Impact of atypical retardation patterns on detection of glaucoma progression using the GDx with variable corneal compensation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;148:155–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Medeiros FA, Bowd C, Zangwill LM, et al. Detection of glaucoma using scanning laser polarimetry with enhanced corneal compensation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3146–53. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Medeiros FA, Alencar LM, Zangwill LM, et al. The relationship between intraocular pressure and progressive retinal nerve fiber layer loss in glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1125–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.12.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]