Abstract

Pax3 is a transcription factor expressed in somitic mesoderm, dorsal neural tube and pre-migratory neural crest during embryonic development. We have previously identified cis-acting enhancer elements within the proximal upstream genomic region of Pax3 that are sufficient to direct functional expression of Pax3 in neural crest. These elements direct expression of a reporter gene to pre-migratory neural crest in transgenic mice, and transgenic expression of a Pax3 cDNA using these elements is sufficient to rescue neural crest development in mice otherwise lacking endogenous Pax3. We show here that deletion of these enhancer sequences by homologous recombination is insufficient to abrogate neural crest expression of Pax3 and results in viable mice. We identify a distinct enhancer in the fourth intron that is also capable of mediating neural crest expression in transgenic mice and zebrafish. Our analysis suggests the existence of functionally redundant neural crest enhancer modules for Pax3.

Introduction

Pax3 is a paired-domain containing nuclear transcription factor that is required for normal neural crest and skeletal muscle development. Mutation of Pax3 results in embryonic lethality and multiple defects in tissues of neural crest and somitic origin as seen in the naturally occurring Splotch mutant (Auerbach, 1954). In humans, mutations in PAX3 result in Waardenburg syndrome which is characterized by neural crest abnormalities (Tassabehji et al., 1993). We and others have sought to better understand gene regulation in this critical tissue through analysis of cis-acting elements in the Pax3 locus. Toward this end, 1.6 Kb of genomic sequence upstream of the Pax3 transcription start site has been found to be capable of driving reporter gene expression in the neural crest of transgenic mice (Li et al., 1999; Natoli et al., 1997; Pruitt, 1994). The use of this genomic region to express Pax3 in transgenic mice is well tolerated and is sufficient to rescue neural crest defects in Splotch mice, including conotruncal cardiac abnormalities (Li et al., 1999). Furthermore, we have shown that transgenic mice in which the 1.6 Kb Pax3 upstream genomic region directs expression of Cre recombinase can be used to fate-map neural crest derivatives when crossed with appropriate Cre reporter mice (Li et al., 2000). A distinct upstream enhancer that mediates hypaxial somite expression of Pax3 has also been identified more than 6 Kb upstream of the transcription start site (Brown et al., 2005).

The 1.6 Kb Pax3 upstream region contains two evolutionarily conserved elements that are critical for the neural crest expression (Milewski et al., 2004; Pruitt et al., 2004). These two conserved elements, each about 250 bp in length, are located within a 674 bp region that we heretofore refer to as “NCE” (neural crest element). The NCE contains a binding site for the transcription factor Tead2 which we have shown is co-expressed with Pax3 in the dorsal neural tube and which, along with its co-activator YAP65, can regulate Pax3 expression (Milewski et al., 2004). However, more recent inactivation of Tead2 in mice failed to significantly alter Pax3 expression although neural tube defects were produced (Kaneko et al., 2007). Taken together with our prior work showing the necessity for the Tead2 binding site in the Pax3 NCE for appropriate activation in transgenic mice, this suggests the existence of redundant mechanisms for regulation of Pax3 neural crest expression outside the NCE.

Here, we show that targeted deletion of the Pax3 NCE does not detectably alter Pax3 expression and results in viable mice. The NCE was targeted using a floxed PGK-neo cassette which, when left in place, disrupts Pax3 expression thus producing a new allele of Splotch. Removal of the PGK-neo cassette with various cre-expressing mice allows for tissue-specific rescue of Pax3 function. We identify a previously unrecognized enhancer in the fourth Pax3 intron that directs neural tube and neural crest expression, and functions redundantly with the upstream NCE in transgenic mice. Sequence analysis reveals the presence of NFY and Lef1 binding sites in both neural crest enhancer elements that are maintained through evolution.

Experimental Procedures

Gene targeting and generation of neural crest enhancer deleted mice

The targeting construct involved modification of pPNT containing an HSV-TK cassette for negative selection. The targeting strategy involved deletion of a 674bp neural crest enhancer region (corresponding to position 21231-20621 of GenBank AC084043) previously described (Li et al., 1999; Milewski et al., 2004) and replacement with a floxed PGK-neo cassette (Fig. 1a).

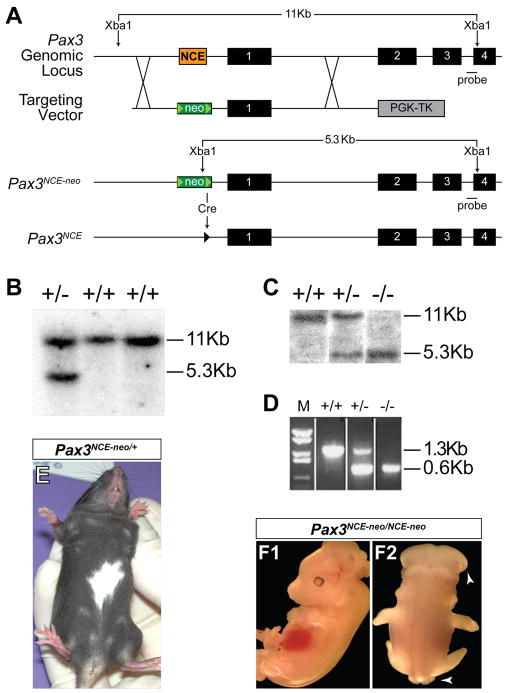

Figure 1. Targeted Deletion of the Pax3 upstream NCE.

(A). Schematic representation of targeting strategy. The NCE (orange box) is replaced by a floxed neomycin resistance cassette (neo) to produce the Pax3NCE-neo allele after homologous recombination. Cre recombinase removes the neomycin cassette, leaving a single loxP site (green triangle), to produce Pax3NCE. (B, C). Confirmation of targeted ES cells (B) and mice (C) by Southern blot using a probe 3′ of the targeting arms. (D). After cre recombination, the removal of the NCE is confirmed by PCR. E. Pax3NCE-neo/+ mice have white belly spots. (F). Pax3NCE-neo/NCE-neo E13.5 embryos have neural tube defects (white arrows).

Synthesis of the 5′ homology arm was accomplished by PCR using the primers:

5′ Forward, 5′-CCCGGCGCGCCGCTATGCAGATTACATTTCCTACGTATCCC-3′;

5′ Reverse, 5′-GGTGACCCTCACTTGAGAATTTCCCGGTCGGAGCTCGGC-3′

Synthesis of the 3′ homology arm was accomplished by PCR using the primer:

3′ Forward, 5′-GCCGTTAACTTCAGCTTGCAACTTGGAGCCCAGGGGAGG – 3′

3′ Reverse, 5′-GCCTTAATTAAGGCCTGCCGTTGATAAATACTCCTCCGAGC – 3′.

The targeting construct was used to electroporate R1 ES cells (kindly provided by Andras Nagy, Mount Sinai Medical Center, Toronto, Canada) producing 13 of 412 clones that were correctly targeted as assessed by Southern blot, and 3 were injected into B6SJLF blastocysts producing 9 chimeric founders. Germline transmission for the heterozygous Pax3NCE-neo/+ (Neural Crest Enhancer deleted with neo) allele was confirmed by Southern blot. Pax3NCE/+ mice (Neural Crest Enhancer deleted, neo removed) and Pax3NCE-neo mice were bred to BALB/c-TgN(CMV-Cre)1Cgn (Stock Number 003465, Jackson Laboratory) on a CD1 background as well as B6.FVB-Tg(EIIa-cre)C5379Lmgd/J (Stock Number 003724, Jackson Laboratory) mice on a B6 background and removal of the neo cassette was confirmed by PCR.

Genotyping of embryos and mice

Genotyping Pax3NCE-neo and Pax3NCE was performed by PCR using the following primers:

Pax3 Upstream Forward: 5′-CTGAGTGTGCAGCCTGAATTTAACCACTTG -3′

Pax3 Downstream Reverse: 5′-AAGACCCTCCGAGTGTATCCCTCGCGTCCG -3′

Neo Forward: 5′-TTCAAAAGCGCACGTCTGCCGCGC – 3′

This strategy generated a 1.3Kb wild type band and a 600bp band when the floxed neo cassette was present in place of the neural crest enhancers. A 400 bp band was produced when the floxed neo cassette was deleted by cre-mediated recombination.

Genotyping for lacZ was performed by PCR using the following primers:

lacZ genotype Forward: 5′ – ATCACGACGCGCTGTATCGCTG – 3′

lacZ genotype Reverse: 5′ – CACTGAGGTTTTCCGCCAG – 3′

The presence of the lacZ gene results in a 783 bp product. Wnt1-cre (Jiang et al., 2002), Pax3Cre (Engleka et al., 2005) and P34TKZ Pax3 reporter (Relaix et al., 2004) mice have been described.

Generation of transgenic mice

An evolutionarily conserved region of the Pax3 genomic locus in the fourth intron, termed ECR2, was amplified by PCR using the following primers:

Pax3 Int Forward: 5′-GGCTCGAGGAGGGGATGTGCTATTTGAGATTTCGG-3′

Pax3 Int Reverse: 5′-GGCTCGAGGTGTATTCACCTAGTCCATTTGATGATTGG-3′

These primers amplify the region corresponding to chr1:78,164,002-78,164,969 of the mouse July 2007 NCBI Build 37 mouse genome assembly (mm9). Primer sequences for amplification of additional evolutionary conserved regions of the Pax3 locus are provided in supplemental methods. The amplified regions were subcloned upstream of the lacZ gene with either an hsp68 minimal promoter or a promoter region derived from the endogenous Pax3 gene, as described in the results section. Transgenic mice were generated by injection of linearized DNA into the male pronucleus of C57BL6xSJL-F1/J zygotes. Embryos were harvested at E10.5 for analysis of β-galactosidase expression and genotype.

Generation of transgenic zebrafish

The evolutionarily conserved region (ECR2) of the Pax3 genomic locus was PCR amplified using the attB1 int4-3 F (5′-GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTGAGGGGATGTGCTATTTGAGATT TCGG-3′)/attB2 int4-3 R (5′-GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTGTGTATTCACCTAGTCCATTTGAT GATTGG-3′) primer pair, cloned into pDONR221 (Invitrogen) by Gateway recombination, and the resulting plasmid was designated pME-ECR2. The Lef1/TCF binding sites in pME-ECR2 were mutated by synthesis of a 403-bp sequence-verified Bu36I/BsaI flanked miniGene (Integrated DNA Technology) engineered to harbor mutations in all of the Lef1/TCF sites, BSU36I/BsaI restriction digestion, and ligation of this fragment into a Bsu36I/BsaI restriction digested pME-ECR2 vector backbone, thus generating the plasmid designated pME-ECR2ΔLef. pME-ECR2 was then recombined into the pGW_cfosEGFP and pGW_cfosmCherry Tol2 trasngenic expression plasmids (Fisher et al., 2006) by LR recombination (Invitrogen); pME-ECR2ΔLef was cloned into pGW_cfosmCherry. Wild type and Tg(sox10:GFP) (Antonellis et al., 2008) zebrafish embryos were injected with an approximately 2nl volume containing 10pg of the appropriate transgenic expression plasmid and 35pg of transposase RNA suspended in nuclease free water supplemented with phenol red (10% v/v).

β-galactosidase staining

Embryos were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 5–15 minutes on ice. After washing briefly in PBS, they were stained in 1 mg/ml X-gal, 5 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 5 mM K4Fe(CN)6, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.01% NP-40, 0.01% sodium deoxycholate, in PBS. Staining reactions were carried out for 2 hours to overnight at 37 °C.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Embryos were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours, then dehydrated in 100% ethanol, fixed in paraffin and sectioned. The Pax3 and MyoD (D7F2) monoclonal antibodies generated by C. Ordahl and J. Gurdon, respectively were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by The University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City, IA 52242. For LacZ and Pax3 double staining, embryos were stained for β-galactosidase as described above. The embryos were then dehydrated in methanol. Pax3 whole mount immunohistochemistry was carried out using a standard protocol as previously described (Singh et al., 2005). Briefly, embryos were rehydrated and probed with Pax3 antibody overnight at 4°C at a dilution of 1:100. The secondary antibody was goat-anti-mouse IgG-HPR (Santa Cruz biotechnology sc-2005) used at a dilution of 1:1000 for 4 hrs at room temperature. After washing, signals were detected using diaminobenzidine and H2O2.

Results

Targeted deletion of the neural crest enhancer region

We have previously identified two ~250 bp enhancer elements within the upstream Pax3 genomic region that are sufficient to recapitulate the Pax3 expression pattern in the neural crest, and to direct functional expression of Pax3 (Li et al., 1999; Milewski et al., 2004). We sought to test whether these enhancer elements are also necessary in vivo for Pax3 expression in the neural crest. Here, we refer to these upstream neural crest elements collectively as “NCE”.

We generated a mutant Pax3 allele in which a 674 bp region, which encompasses the NCE (Milewski et al., 2004), was deleted using homologous recombination. The targeted allele resulted in the replacement of the NCE with a PGK-neo cassette flanked by loxP sites (Fig. 1a), and we designated this allele Pax3NCE-neo. Appropriate targeting of ES cells was confirmed by Southern blotting (Fig. 1b) and 3 independent clones were used to generate chimeras, which subsequently yielded germline transmission of the targeted Pax3 allele, as assessed by Southern blotting (Fig. 1c) and PCR (Fig. 1d).

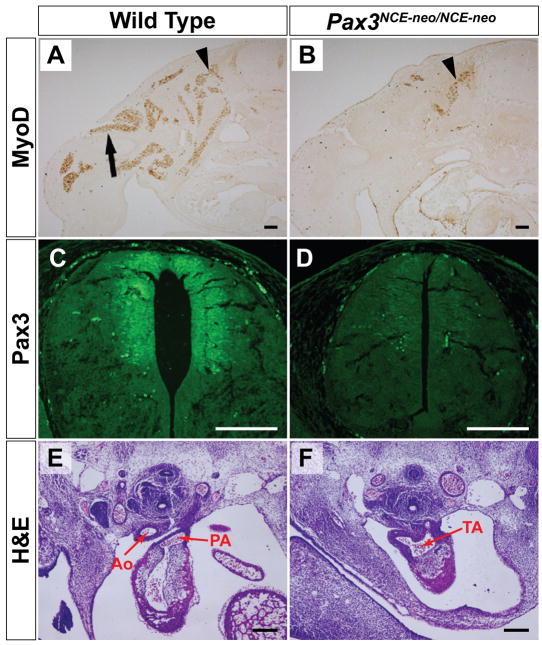

Replacement of the NCE with PGK-neo results in loss of Pax3 expression

Pax3NCE-neo/+ mice displayed a coat color defect characterized by a white belly spot (Fig. 1e) similar to that seen in Splotch heterozygous mice carrying a null allele for Pax3 (Auerbach, 1954). Pax3NCE-neo/+ mice otherwise appeared normal and were viable and fertile. Intercrosses of Pax3NCE-neo/+ mice were established but failed to yield any viable Pax3NCE-neo/NCE-neo homozygous offspring among more than 20 litters, suggesting embryonic lethality. Therefore, timed matings were established and embryos were harvested at E12.5, just prior to the time of embryonic lethality for Pax3-deficient Splotch homozygotes (Auerbach, 1954). At E12.5, Pax3NCE-neo/NCE-neo embryos were identified in the expected Mendelian ratios (17 of 66 embryos genotyped). Pax3NCE-neo/NCE-neo embryos exhibited exencephaly and spina bifida (Fig. 1f). Hypaxial muscle development was also markedly deficient, as evidenced by the lack of MyoD-expressing myoblasts in the developing limbs (Fig. 2a,b) and by routine histology and gross inspection (data not shown). These abnormalities are similar to those seen in homozygous Splotch embryos (Auerbach, 1954) and suggest severe loss of Pax3 function. Direct examination of Pax3 expression by immunohistochemistry showed a drastic reduction or complete loss of Pax3 protein in Pax3NCE-neo/NCE-neo embryos (Fig. 2c,d). Conotruncal cardiac defects including persistent truncus arteriosus were also seen (Fig. 2e,f) consistent with the Splotch phenotype and loss of Pax3 function in cardiac neural crest. Hence, Pax3NCE-neo represents a new allele of Splotch and a null or severely hypomorphic allele of Pax3.

Figure 2. Pax3NCE-neo/NCE-neo embryos display cardiac and limb muscle defects at E12.5.

(A, B). Immunohistochemistry with a MyoD antibody reveals hypaxial myoblasts (black arrow) that have appropriately migrated to the limb in the wild type embryo (A), while no MyoD positive cells are detected in the limb of the Pax3NCE-neo/NCE-neo mutant (B). Epaxial myoblasts expressing MyoD (arrowhead) are present. (C, D). Pax3 protein is expressed in the dorsal neural tube of wild type (C) but not Pax3NCE-neo/NCE-neo (D) embryos. (E, F). H&E staining reveals septation of the aorta (Ao) and pulmonary artery (PA) in wild type embryo (E), while the truncus arteriosus (TA) is unseptated in the Pax3NCE-neo/NCE-neo littermate (F). Scale bar = 200 microns.

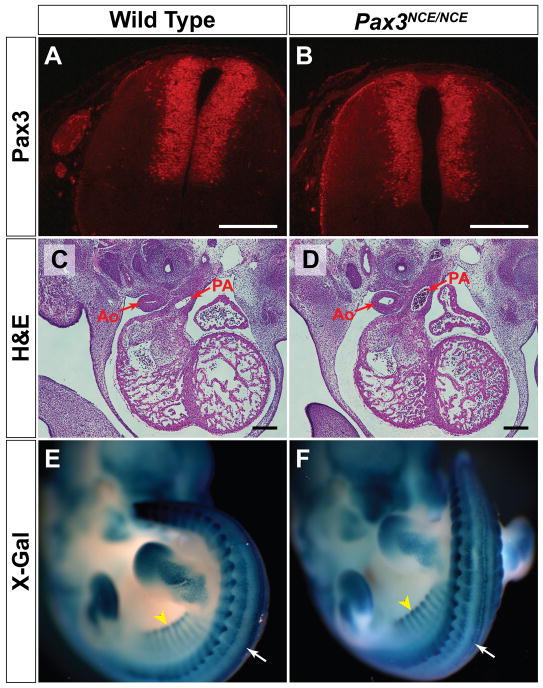

Removal of the PGK-neo cassette restores Pax3 expression

To determine if the phenotype observed in Pax3NCE-neo/NCE-neo embryos was related to the presence of the PGK-neo cassette, the heterozygous Pax3NCE-neo/+ mice were crossed with transgenic mice ubiquitously expressing cre in order to remove the floxed PGK-neo cassette in all tissues (Figure 3). Heterozygous mice with the PGK-neo cassette removed, designated Pax3NCE/+, had no obvious phenotypes and no coat color abnormalities. Surprisingly, homozygous Pax3NCE/NCE mice also appeared normal, are born in the expected Mendelian ratios (Table 1), and are fertile. Immunohistochemistry of E11.5 Pax3NCE/NCE embryos revealed apparently normal level and distribution of Pax3 protein compared to wild type littermates (Fig. 3a,b). Septation of the outflow tract, a process that requires Pax3 function in cardiac neural crest, was normal (Fig. 3c,d) as was neural tube closure, dorsal root ganglia development, and skeletal muscle formation as assessed by routine histology (Fig. 3 and data not shown).

Figure 3. Removal of the PGK-neo cassette restores Pax3 expression, and results in normal conotruncal anatomy and Pax3 transcriptional activity despite the loss of the NCE.

(A, B). Immunohistochemistry reveals normal Pax3 expression in the dorsal neural tube of an E12.5 Pax3NCE/NCE embryo (B) as compared to wild type (A). (C, D). Both wild type (C) and Pax3NCE/NCE (D) mice have normal septation of the aorta (Ao) and pulmonary artery (PA) at E12.5. E, F. X-gal staining of P34TKZ Pax3 reporter mice at E11.5 reveals normal expression of β-galactosidase in the neural crest (white arrow) and somites (black arrowhead) in wild type (E) and Pax3NCE/NCE (F) mice. Scale bar = 200 microns.

Table 1.

Genotypes of offspring from Pax3NCE/+x Pax3NCE/+ matings at weaning.

| Pax3+/+ | Pax3NCE/+ | Pax3NCE/NCE | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual | 33 (24%) | 66 (48%) | 38 (28%) | 137 |

| Predicted | 34 (25%) | 69 (50%) | 34 (25%) |

In addition to extensive phenotyping and analysis of Pax3 protein expression in various tissues in the embryo and adult, we also sought to identify subtle abnormalities of Pax3 function by examining transcriptional activity in vivo. We crossed Pax3NCE/NCE to a transgenic P34TKZ Pax3 reporter line (Relaix et al., 2004) that contains concatamers of Pax3 binding sites upstream of lacZ, and expresses β-galactosidase in Pax3 expressing tissues (Fig. 3e). Homozygous Pax3NCE/NCE mice show the same pattern of β-galactosidase expression as wild type mice (Fig. 3e,f) suggesting normal Pax3 transcriptional activity throughout the embryo. We also sought to determine if Pax3NCE/NCE mice have defects in adult melanocytes, but failed to detect any abnormalities induced by depilation of hair or tanning (data not shown). Thus, it appears that the 674bp NCE region in the Pax3 promoter that is sufficient to direct neural crest expression in transgenic mice is not required for Pax3 expression or transcriptional activity in vivo.

The Pax3NCE-neo allele allows for tissue-specific rescue of Pax3 expression

These results indicate that Pax3NCE-neo acts as a null allele while removal of the floxed PGK-neo cassette restores functional levels of Pax3 expression. Hence, we sought to demonstrate that tissue-specific expression of cre recombinase would allow for tissue-specific rescue of Pax3 expression. As a first step, we crossed Pax3NCE-neo/+ mice to Pax3Cre/+ mice in which cre recombinase is knocked into the Pax3 locus (Engleka et al., 2005), and Pax3NCE-neo/Cre offspring were generated. We have previously shown that the Pax3Cre allele is a null allele of Pax3 (Engleka et al., 2005). Hence, Pax3NCE-neo/Cre mice can only be viable if cre-mediated removal of the PGK-neo cassette in the Pax3NCE-neo allele restores Pax3 expression in critical tissues and at critical time points. Pax3NCE-neo/Cre mice were viable and had normal development of neural crest derivatives, including normal cardiac outflow tract and aortic arch derivatives (Supplemental Fig. 1a,b). These mice also demonstrated normal hypaxial muscle development (Supplemental Fig. 1c). Thus, the Pax3NCE-neo/+ mouse can be used as a genetic tool to delineate the tissue-specific role of Pax3.

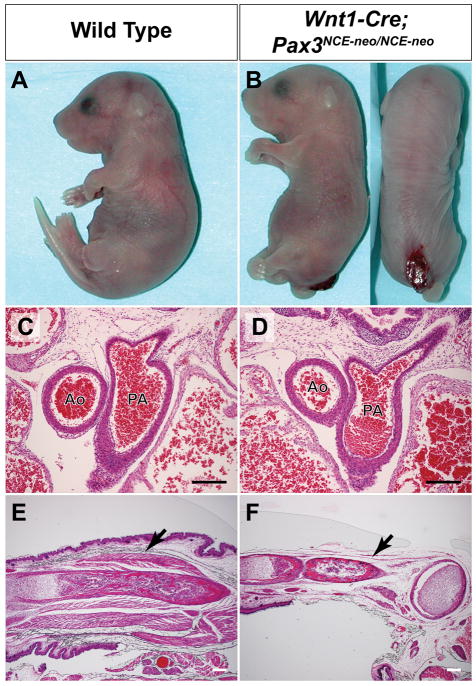

Restoration of Pax3 expression in neural crest rescues embryonic lethality

Next, we sought to investigate the effects of tissue-specific rescue of Pax3 expression in neural crest by crossing Pax3NCE-neo/+ mice with Wnt1-cre, Pax3+/− mice to produce Wnt1-cre, Pax3NCE-neo/− offspring, which would be predicted to have normal Pax3 expression in neural crest but deficient Pax3 expression in somites. Wnt1 is expressed in the dorsal neural tube and neural crest progenitors. The Wnt1 promoter/enhancer has been previously characterized (Jiang et al., 2000; Serbedzija and McMahon, 1997) and is known to direct expression in neural crest cells in a pattern that overlaps with Pax3 (Brown et al., 2001; Jiang et al., 2000).

Wnt1-cre, Pax3NCE-neo/− mice were born alive, but died immediately after birth. The pups appeared cyanotic and were smaller than wild type littermates. Limb and diaphragm musculature were poorly developed and the pups failed to initiate respirations, as evidenced by lungs that were not inflated (data not shown). Occasional mild spina bifida was present (Fig. 4a,b), likely due to the difference in temporospacial expression patterns between Pax3 and Wnt1-cre in the neural crest domain (Supplemental Fig. 2). Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue sections through the right ventricular outflow tract of rescued pups revealed no evidence of persistent truncus arteriosus (Fig. 4c,d), while skeletal muscle was severely deficient in the limbs (Fig. 4e,f). We conclude that tissue-specific rescue of Pax3 expression in the Wnt1-cre expression domain is sufficient to rescue embryonic development, but fails to rescue skeletal muscle formation.

Figure 4. Restoration of Pax3 expression in neural crest rescues embryonic development.

(A, B). Wnt1-cre, Pax3NCE-neo/NCE-neo mice survive to birth, but occasionally display spinal bifida (B) not seen in control littermates (A). (C–F). H&E staining of newborns shows normal septation of the aorta (Ao) and pulmonary artery (PA) in both wild type (C) and Wnt1-cre, Pax3NCE-neo/NCE-neo mice (D), but severe deficiency of forelimb musculature in Wnt1-cre, Pax3NCE-neo/NCE-neo mice (arrow, F) as compared to wild type (arrow, E). Scale bar = 200 microns.

Identification of a potentially redundant neural crest enhancer

As deletion of the previously characterized neural crest enhancer, NCE, from the Pax3 locus failed to perturb neural crest development, we sought to identify other potentially redundant enhancers. Previous efforts to identify Pax3 regulatory elements have focused on the genomic regions upstream of the first exon. We therefore concentrated on intronic and downstream sequences to identify novel Pax3 enhancers. We hypothesized that such cis-acting elements may be well conserved in evolution. We used the NCBI DCODE comparative genomics resource (http://www.dcode.org) to identify 8 evolutionarily conserved regions (ECRs) in the Pax3 locus (Supplemental Fig. 3a). The ECRs were defined by a minimum length of 200 bp, and a minimum identity of 50% between the mouse and chicken syntenic regions. The elements ranged in size from ~400 bp to 1kb. Each of these elements was PCR amplified and subcloned upstream of the hsp68 minimal promoter and lacZ. Transient transgenic mice were generated and analyzed at E10.5 for reporter activity.

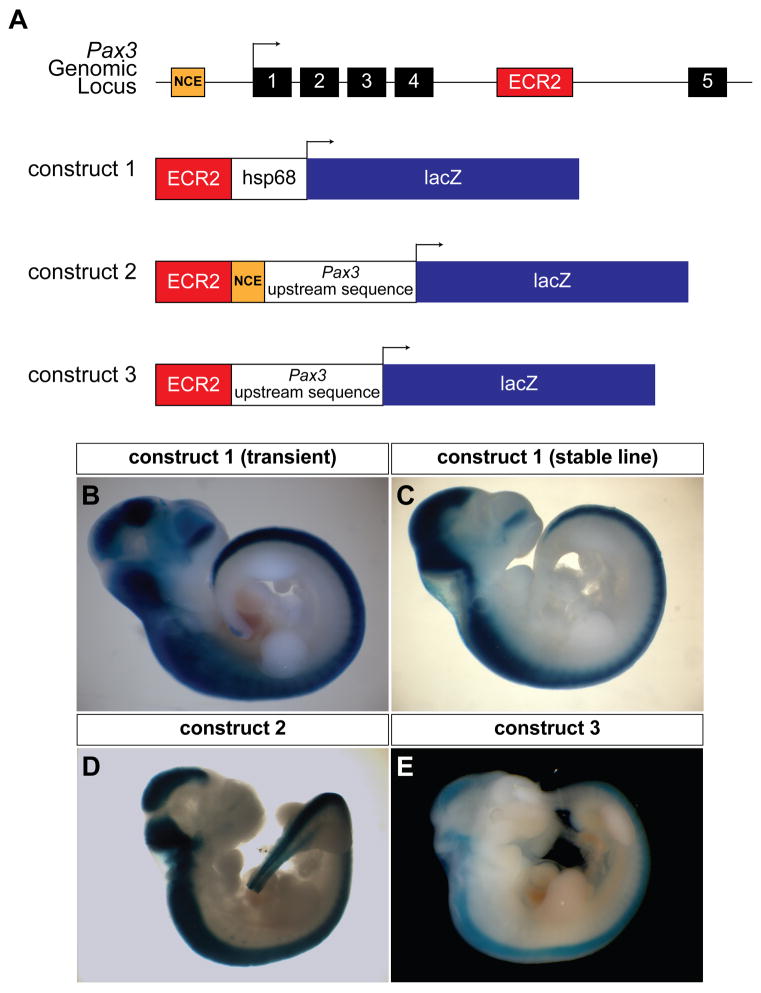

Two ECRs resulted in reproducible patterns that recapitulated aspects of endogenous Pax3 expression (Supplemental Fig. 3b). ECR2 (Supplemental Fig. 3c) and ECR 4 are both in the 4th intron and each confers dorsal neural tube expression in transgenic embryos. The expression seen from ECR2 (Fig. 5a,b) was more robust, and extended to the dorsal extreme or the neural tube unlike the pattern seen with ECR4 (data not shown). Therefore, we sought to analyze ECR2 in more detail.

Figure 5. ECR2 directs neural crest expression in transgenic mouse embryos.

(A). Schematic representation of the region of the Pax3 locus containing the NCE (orange box) and ECR2 (red box). Black boxes represent exons. Three transgene constructs are depicted using ECR2 with the hsp68 minimal promoter as well as Pax3 upstream sequence with and without the NCE. (B). E10.5 transient transgenic embryo showing strong dorsal neural tube expression throughout the anterior-posterior axis. (C). The same pattern is seen in the stable line with Construct 1. (D). Transient transgenic embryo with ECR2 and the 1.6 kb Pax3 upstream region shows robust dorsal neural tube expression. (E). Transient transgenic embryo showing dorsal neural tube expression despite the removal of the NCE from the Pax3 upstream sequence.

A stable line of transgenic mice was generated with this construct, which recapitulated the expression pattern of transient transgenic embryos (Fig. 5c, Supplemental Fig. 4). ECR2 gives robust expression along the antero-posterior axis of the neural tube, unlike the more variable pattern seen with related transgenic constructs containing the upstream NCE (Li et al., 1999; Milewski et al., 2004; Natoli et al., 1997). We tested ECR2 in combination with the Pax3 1.6 Kb upstream genomic region that contains the NCE and the minimal Pax3 promoter (Li et al., 1999) which replaces the hsp68 promoter (Fig. 5a,d, Supplemental Fig. 3b). Again, dorsal neural tube expression was detected along the entire antero-posterior axis in a pattern that recapitulates endogenous Pax3 expression (Fig. 5d). Next, we sought to eliminate activity of the NCE in the setting of this transgene in order to determine if ECR2, like NCE, is able to function with the endogenous minimal Pax3 promoter to drive dorsal neural tube expression. We have previously shown that deletion of the NCE in the context of the 1.6 Kb upstream Pax3 genomic region is sufficient to eliminate expression (Milewski et al., 2004). However, deletion of the NCE in the context of the related construct that also contains ECR2 (Fig. 5a, Construct 3) failed to eliminate neural crest expression (Fig. 5e). Taken together, these observations demonstrate redundancy of cis-regulatory elements in the Pax3 locus that direct neural crest expression, at least in the context of our transgenic analysis.

Analysis of Lef1 sites in ECR2 using zebrafish

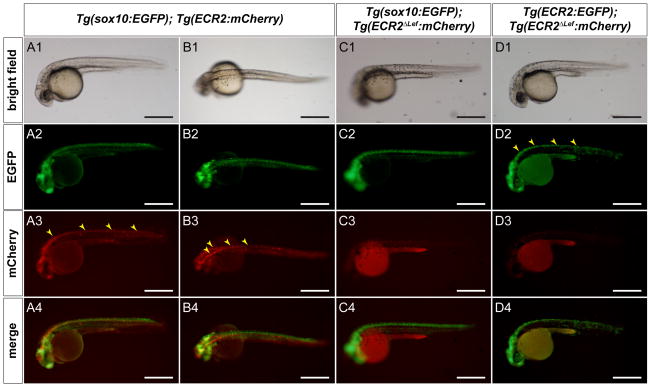

Although direct sequence comparisons of the upstream NCE and ECR2 failed to identify significant homology, more sophisticated analysis revealed conserved motifs. We used rVista version 2.0 (Loots and Ovcharenko, 2004) to identify NFY and Lef1/TCF binding sites that are conserved between mouse and chicken genomes, and also present in both the NCE and ECR2. NFY and Lef1/TCF sites occur within 60 bp of each other in both enhancers. Wnt signaling has been shown to function upstream of Pax3 expression, although direct activation of Pax3 expression via Lef/TCF binding has not been demonstrated (Bang et al., 1999; Burstyn-Cohen et al., 2004; Taneyhill and Bronner-Fraser, 2005). In order to test the functional significance of the Lef/TCF sites identified in ECR2 (Supplemental Fig. 5) we utilized the zebrafish model system because of the ability to rapidly produce and assess transgenic expression and to co-express multiple transgenic constructs in a single embryo. ECR2 directs expression of the reporter genes mCherry and EGFP, in the dorsal neural tube of zebrafish embryos in a pattern that overlaps with that of Sox10, a marker of neural crest (Antonellis et al., 2008) (Figure 6a,b). Twenty-six of 79 injected embryos showed this expression pattern. Mutation of the Lef/TCF sites largely abolished expression in this assay (weak expression or ectopic expression was seen in 1 of 97 injected embryos) (Figure 6c). Furthermore, co-injection of wild type ECR2 driving EGFP expression with a mutant form of ECR2 lacking Lef/TCF binding sites driving mCherry expression resulted in 36 embryos with dorsal neural tube expression of EGFP, while none expressed mCherry (Figure 6d). Thus, intact Lef/TCF sites are required for enhancer activity of ECR2 in this system.

Figure 6. Analysis of transgenic zebrafish shows that ECR2 directs expression to the dorsal neural tube and that this expression requires Lef1/TCF sequences.

(A1–A4). Lateral view of a 1 dpf zebrafish embryo that is stably transgenic for Sox10:EGPF and transiently transgenic for ECR2:mCherry demonstrates strong dorsal neural tube expression (yellow arrowheads). (B1–B4). Dorsal view of a similarly injected embryo as shown in column A. (C1–C4). Lateral view of a 24hpf zebrafish embryo that is stably transgenic for Sox10:EGPF and injected with an ECR2ΔLef:mCherry transgene shows that mutations in the Lef1/TCF sequences abrogates expression. (D1–D4). Lateral view of a 24 hpf zebrafish embryo that has been injected with both ECR2:EGFP and ECR2ΔLef:mCherry transgenes shows EGFP expression in the dorsal neural tube (yellow arrowheads). Despite effective transposase activity, no mCherry expression is detected. Scale bar = 500 microns.

Discussion

In this report, we provide evidence for redundancy among enhancer elements that mediate dorsal neural tube and neural crest expression of Pax3. Our prior studies have indicated that the upstream neural crest enhancer regions are not only able to direct expression of a marker gene to the dorsal neural tube but are also able to direct functional expression of Pax3 to the neural tube and neural crest. Thus, Pax3-deficient Splotch embryos that express transgenic Pax3 from these elements exhibit functional rescue that includes neural tube closure and proper septation of the cardiac outflow tract (Li et al., 1999).

To our surprise, however, our present studies indicate that these upstream enhancer elements are, to the best of our ability to test, completely dispensable for normal Pax3 expression and function. Mice with homozygous deletion of the upstream neural crest enhancer elements develop normally, exhibited normal Pax3 protein expression in all tissues examined, and fail to display any discernable phenotypes. When crossed to Splotch to produce Pax3Sp/NCE mice in order to examine the NCE allele on a sensitized background, the phenotype is indistinguishable from Pax3Sp/+ (that is, only a white belly spot is seen) (data not shown). Our attempts to measure Pax3 transcriptional activity using a Pax3-reporter mouse also show normal function of the NCE allele. Thus, we conclude that the NCE enhancer region is sufficient to mediate neural crest expression of Pax3, but is not necessary.

This conclusion led us to search for and identify potentially redundant enhancer regions that could mediate neural crest expression of Pax3 in the absence of NCE. Our data suggests that a redundant enhancer, ECR2, exists within intron 4.

The literature is replete with examples of functional redundancy among genes, and biologists generally accept the notion that redundant coding regions protect organisms and species from the detrimental effects of random mutation (Blackwood and Kadonaga, 1998; Krakauer and Nowak, 1999; Raes and Van de Peer, 2003). However, examples of functional redundancy among enhancer elements are less common. This is likely to be primarily due to the fact that fewer enhancer elements have been targeted for deletion by homologous recombination, and it may also be due to under-reporting of benign phenotypes after enhancer inactivation. However, functional redundancy among regulatory control regions provides theoretical protection to the organism against mutation of critical sequences that might otherwise result in detrimental phenotypes, perhaps contributing to the persistence of this type of redundancy through evolution. Indeed, distant but functionally overlapping control elements regulate expression of MyoD, and specific deletion by homologous recombination of one of these elements results in relatively subtle defects (Chen and Goldhamer, 2004; Chen et al., 2002). Functional redundancy of enhancer elements in the T-cell receptor (TCR) gamma locus has been demonstrated by gene targeting, although in this case the individual enhancers display both overlapping and unique functions (Xiong et al., 2002).

Our studies do not rule out the possibility that the upstream NCE and ECR2 possess distinct, in addition to partially overlapping, functions. We have not inactivated ECR2 by homologous recombination in order to assess the necessity for this element, and it remains possible that additional partially redundant enhancers exist that also control Pax3 expression in the neural tube and neural crest. Indeed, ECR4, described in this study, may serve such a purpose. Furthermore, it is possible that on different genetic backgrounds or under different environmental conditions the upstream NCE displays unique regulatory characteristics distinct from those of ECR2. For example, the upstream NCE is responsive to retinoic acid (Natoli et al., 1997) and both vitamin A and folate exposure can affect Pax3 expression and related neural crest phenotypes (Bang et al., 1997; Burren et al., 2008; Fleming and Copp, 1998; Wlodarczyk et al., 2006). Perhaps mice lacking either the upstream NCE or ECR2 would be more or less sensitive to genetic or environmental perturbations in vitamin A, folate, or other signals. Such a mechanism could also contribute to evolutionary pressure to conserve these elements.

We identified evolutionary conservation of NFY and Lef1/TCF bindings sites in the two redundant neural crest enhancers within the Pax3 locus. We focused our attention on the functional significance of the conserved Lef1/TCF bindings sites, which we demonstrated using transgenic zebrafish. Evidence in the published literature suggests that the NFY binding sites may also be functionally significant. For example, the NFY site in the NCE overlaps with a Pbx1 site that has previously been shown to directly regulate expression of Pax3 both in vitro and in vivo (Chang et al., 2008; Pruitt et al., 2004). Pbx1 binds to the upstream neural crest enhancer and activates expression of a reporter gene in transfection assays (Chang et al., 2008; Pruitt et al., 2004) and expression of the 1.6 Kb Pax3 transgene is diminished in Pbx1−/− embryos (Chang et al., 2008). Mutation of a Pbx1 binding site within the 1.6Kb promoter/enhancer region largely abrogates neural tube expression (Chang et al., 2008).

We searched for related enhancer sequences elsewhere in the genome. Using synoR analysis (Ovcharenko and Nobrega, 2005), potential regulatory modules containing NFY and Lef1/TCF bindings sites, within a 60bp span, conserved between mouse and chicken are identified in 594 locations in the mouse genome. Eight of these modules are identified in the proximal upstream region of known genes and 197 modules are found in intronic regions of known or predicted genes. This analysis identifies several genes known to be expressed in the neural crest, including Meis2, Msx2, and Mef2C.

The targeting procedure that we adopted to delete the NCE fortuitously resulted in the creation of a new allele of Splotch when the floxed PGK-neo cassette was inserted in place of the targeted enhancer sequences. The dramatic impairment of Pax3 mRNA and protein expression induced by insertion of this cassette was likely due to promoter competition produced by the presence of the PGK sequences. The NCE-neo allele allows for tissue-specific rescue of Pax3 expression by cre-mediated recombination. By crossing mice carrying the NCE-neo allele with those in which Cre had been knocked into the Pax3 locus, we were able to dramatically rescue near normal Pax3 expression and embryonic development. Neural crest-specific excision of the neo cassette resulted in rescue of neural crest-related embryonic defects such as neural tube closure and cardiac septation. This result suggests a neural-crest autonomous role for Pax3 with respect to these phenotypes, a conclusion that has been previously challenged by mouse-chick transplantation studies suggesting that Pax3 expression in the somite adjacent to neural crest migratory pathways might contribute to neural crest defects in Splotch (Serbedzija and McMahon, 1997). Furthermore, we have previously described an upstream Pax3 enhancer that mediates hypaxial somite expression and we have generated transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase in this domain (Brown et al., 2005). By crossing these mice with the NCE-neo allele, we restored Pax3 expression to the hypaxial somite, but failed to rescue either neural crest or skeletal muscle development (data not shown), suggesting that expression of Pax3 in this domain was insufficient to support normal neural crest development, and that Pax3 expression in somitic precursors is likely to be required before specialization of the hypaxial domain.

In conclusion, this study highlights the complexity of transcriptional regulatory control of gene expression and, in particular, the need to examine enhancer function in the context of the endogenous chromosome. Transgenic assays for sufficiency should not be confused with rigorous tests for necessity. Furthermore, the lack of overt similarities between two distinct Pax3 enhancers with overlapping function underscores our lack of sophisticated insight into regulatory code and our relatively poor ability to predict enhancer function from sequence. Further detailed analysis of functional redundancy among enhancers will be necessary in order to alleviate these weaknesses.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. The Pax3NCE-neo allele allows for tissue-specific rescue of Pax3 expression. Removal of the PGK-neo cassette in tissues that normally express Pax3 using Pax3cre allows for viable mice (A) shown here at P1, with normally septated aorta (Ao) and pulmonary artery (PA) (B). Forelimb musculature also appears histologically normal (C). Scale bar = 200 microns.

Supplemental Figure 2. Wnt1-Cre activity is not detectable in the posterior neural crest at a time when Pax3 protein is present. (A). X-gal stained E9.5 Wnt1-Cre/R26R-lacZ embryo demonstrates strong anterior neural crest staining (black arrowheads), but no staining in the posterior neural crest (red arrowheads). (B). The same embryo demonstrates Pax3 expression along the entire rostro-caudal axis of the dorsal neural tube by whole mount immunostaining (brown signal). (C and D). Dorsal views of the same double stained embryo.

Supplemental Figure 3. A. Schematic diagram depicting the relative location of Pax3 ECRs (black arrowheads) within and downstream of the Pax3 genomic locus. Just upstream of the first exon is the NCE (orange arrowhead), which is also conserved. The asterisk marks ECR2, which has dorsal neural tube activity. Rectangles represent exons. (B). Summary of transgenic data obtained with the various ECRs. (C). Sequence of murine ECR2 (primer sequences are indicated in bold).

Supplemental Figure 4. Developmental time course of β-galactosidase activity in a stable transgenic mouse line carrying construct 1. (A). Signal is detected in the dorsal neural tube by E8.5, consistent with endogenous Pax3 expression. (B–D). Expression remains essentially restricted to the dorsal neural tube throughout midgestation, though ectopic expression in the ventral forebrain is seen after E10.5. (E). Histologic analysis at E10.5 revealed no additional expression outside the central nervous system.

Supplemental Figure 5. Schematic diagram of constructs used to generate transient zebrafish transgenics and the sequence changes used to mutate Lef1/TCF sites. (A). Three constructs used include the ECR2 with a minimal promoter and either EGFP or mCherry. A third construct contains the ECR2 with five mutated Lef1/TCF sites as detailed in (B).

Acknowledgments

We thank Shannon Fisher and Evanthia Pashos for assistance with zebrafish studies and for supplying reagents, Jean Richa for assistance with the production of transgenic mice, and Michael Pack and Jie He (University of Pennsylvania Zebrafish Core Facility) for assistance with zebrafish husbandry. This work was supported by NIH grants RO1 HL61475 and P01 HL075215 to JAE. AP was supported by a fellowship from the Sarnoff Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Antonellis A, Huynh JL, Lee-Lin SQ, Vinton RM, Renaud G, Loftus SK, Elliot G, Wolfsberg TG, Green ED, McCallion AS, Pavan WJ. Identification of neural crest and glial enhancers at the mouse Sox10 locus through transgenesis in zebrafish. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000174. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach R. Analysis of the developmental effects of a lethal mutation in the house mouse. J Exper Zool. 1954;127:305–329. [Google Scholar]

- Bang AG, Papalopulu N, Goulding MD, Kintner C. Expression of Pax-3 in the lateral neural plate is dependent on a Wnt-mediated signal from posterior nonaxial mesoderm. Dev Biol. 1999;212:366–80. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang AG, Papalopulu N, Kintner C, Goulding MD. Expression of Pax-3 is initiated in the early neural plate by posteriorizing signals produced by the organizer and by posterior non-axial mesoderm. Development. 1997;124:2075–85. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.10.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwood EM, Kadonaga JT. Going the distance: a current view of enhancer action. Science. 1998;281:60–3. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5373.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CB, Engleka KA, Wenning J, Min Lu M, Epstein JA. Identification of a hypaxial somite enhancer element regulating Pax3 expression in migrating myoblasts and characterization of hypaxial muscle Cre transgenic mice. Genesis. 2005;41:202–9. doi: 10.1002/gene.20116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CB, Feiner L, Lu MM, Li J, Ma X, Webber AL, Jia L, Raper JA, Epstein JA. PlexinA2 and semaphorin signaling during cardiac neural crest development. Development. 2001;128:3071–80. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.16.3071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burren KA, Savery D, Massa V, Kok RM, Scott JM, Blom HJ, Copp AJ, Greene ND. Gene-environment interactions in the causation of neural tube defects: folate deficiency increases susceptibility conferred by loss of Pax3 function. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:3675–85. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstyn-Cohen T, Stanleigh J, Sela-Donenfeld D, Kalcheim C. Canonical Wnt activity regulates trunk neural crest delamination linking BMP/noggin signaling with G1/S transition. Development. 2004;131:5327–39. doi: 10.1242/dev.01424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CP, Stankunas K, Shang C, Kao SC, Twu KY, Cleary ML. Pbx1 functions in distinct regulatory networks to pattern the great arteries and cardiac outflow tract. Development. 2008;135:3577–86. doi: 10.1242/dev.022350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JC, Goldhamer DJ. The core enhancer is essential for proper timing of MyoD activation in limb buds and branchial arches. Dev Biol. 2004;265:502–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JC, Ramachandran R, Goldhamer DJ. Essential and redundant functions of the MyoD distal regulatory region revealed by targeted mutagenesis. Dev Biol. 2002;245:213–23. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engleka KA, Gitler AD, Zhang M, Zhou DD, High FA, Epstein JA. Insertion of Cre into the Pax3 locus creates a new allele of Splotch and identifies unexpected Pax3 derivatives. Dev Biol. 2005;280:396–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher S, Grice EA, Vinton RM, Bessling SL, Urasaki A, Kawakami K, McCallion AS. Evaluating the biological relevance of putative enhancers using Tol2 transposon-mediated transgenesis in zebrafish. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1297–305. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming A, Copp AJ. Embryonic folate metabolism and mouse neural tube defects. Science. 1998;280:2107–9. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5372.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Choudhary B, Merki E, Chien KR, Maxson RE, Sucov HM. Normal fate and altered function of the cardiac neural crest cell lineage in retinoic acid receptor mutant embryos. Mech Dev. 2002;117:115–22. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00206-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Rowitch DH, Soriano P, McMahon AP, Sucov HM. Fate of the mammalian cardiac neural crest. Development. 2000;127:1607–16. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko KJ, Kohn MJ, Liu C, DePamphilis ML. Transcription factor TEAD2 is involved in neural tube closure. Genesis. 2007;45:577–87. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakauer DC, Nowak MA. Evolutionary preservation of redundant duplicated genes. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1999;10:555–9. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1999.0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Chen F, Epstein JA. Neural crest expression of Cre recombinase directed by the proximal Pax3 promoter in transgenic mice. Genesis. 2000;26:162–4. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1526-968x(200002)26:2<162::aid-gene21>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Liu KC, Jin F, Lu MM, Epstein JA. Transgenic rescue of congenital heart disease and spina bifida in Splotch mice. Development. 1999;126:2495–503. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loots GG, Ovcharenko I. rVISTA 2.0: evolutionary analysis of transcription factor binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W217–21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milewski RC, Chi NC, Li J, Brown C, Lu MM, Epstein JA. Identification of minimal enhancer elements sufficient for Pax3 expression in neural crest and implication of Tead2 as a regulator of Pax3. Development. 2004;131:829–37. doi: 10.1242/dev.00975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natoli TA, Ellsworth MK, Wu C, Gross KW, Pruitt SC. Positive and negative DNA sequence elements are required to establish the pattern of Pax3 expression. Development. 1997;124:617–26. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.3.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovcharenko I, Nobrega MA. Identifying synonymous regulatory elements in vertebrate genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W403–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt SC. Discrete endogenous signals mediate neural competence and induction in P19 embryonal carcinoma stem cells. Development. 1994;120:3301–12. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.11.3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruitt SC, Bussman A, Maslov AY, Natoli TA, Heinaman R. Hox/Pbx and Brn binding sites mediate Pax3 expression in vitro and in vivo. Gene Expr Patterns. 2004;4:671–85. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raes J, Van de Peer Y. Gene duplication, the evolution of novel gene functions, and detecting functional divergence of duplicates in silico. Appl Bioinformatics. 2003;2:91–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relaix F, Rocancourt D, Mansouri A, Buckingham M. Divergent functions of murine Pax3 and Pax7 in limb muscle development. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1088–105. doi: 10.1101/gad.301004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbedzija GN, McMahon AP. Analysis of neural crest cell migration in Splotch mice using a neural crest-specific LacZ reporter. Dev Biol. 1997;185:139–47. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh MK, Christoffels VM, Dias JM, Trowe MO, Petry M, Schuster-Gossler K, Burger A, Ericson J, Kispert A. Tbx20 is essential for cardiac chamber differentiation and repression of Tbx2. Development. 2005;132:2697–707. doi: 10.1242/dev.01854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taneyhill LA, Bronner-Fraser M. Dynamic alterations in gene expression after Wnt-mediated induction of avian neural crest. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:5283–93. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-03-0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tassabehji M, Read AP, Newton VE, Patton M, Gruss P, Harris R, Strachan T. Mutations in the PAX3 gene causing Waardenburg syndrome type 1 and type 2. Nat Genet. 1993;3:26–30. doi: 10.1038/ng0193-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodarczyk BJ, Tang LS, Triplett A, Aleman F, Finnell RH. Spontaneous neural tube defects in splotch mice supplemented with selected micronutrients. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;213:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong N, Kang C, Raulet DH. Redundant and unique roles of two enhancer elements in the TCRgamma locus in gene regulation and gammadelta T cell development. Immunity. 2002;16:453–63. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. The Pax3NCE-neo allele allows for tissue-specific rescue of Pax3 expression. Removal of the PGK-neo cassette in tissues that normally express Pax3 using Pax3cre allows for viable mice (A) shown here at P1, with normally septated aorta (Ao) and pulmonary artery (PA) (B). Forelimb musculature also appears histologically normal (C). Scale bar = 200 microns.

Supplemental Figure 2. Wnt1-Cre activity is not detectable in the posterior neural crest at a time when Pax3 protein is present. (A). X-gal stained E9.5 Wnt1-Cre/R26R-lacZ embryo demonstrates strong anterior neural crest staining (black arrowheads), but no staining in the posterior neural crest (red arrowheads). (B). The same embryo demonstrates Pax3 expression along the entire rostro-caudal axis of the dorsal neural tube by whole mount immunostaining (brown signal). (C and D). Dorsal views of the same double stained embryo.

Supplemental Figure 3. A. Schematic diagram depicting the relative location of Pax3 ECRs (black arrowheads) within and downstream of the Pax3 genomic locus. Just upstream of the first exon is the NCE (orange arrowhead), which is also conserved. The asterisk marks ECR2, which has dorsal neural tube activity. Rectangles represent exons. (B). Summary of transgenic data obtained with the various ECRs. (C). Sequence of murine ECR2 (primer sequences are indicated in bold).

Supplemental Figure 4. Developmental time course of β-galactosidase activity in a stable transgenic mouse line carrying construct 1. (A). Signal is detected in the dorsal neural tube by E8.5, consistent with endogenous Pax3 expression. (B–D). Expression remains essentially restricted to the dorsal neural tube throughout midgestation, though ectopic expression in the ventral forebrain is seen after E10.5. (E). Histologic analysis at E10.5 revealed no additional expression outside the central nervous system.

Supplemental Figure 5. Schematic diagram of constructs used to generate transient zebrafish transgenics and the sequence changes used to mutate Lef1/TCF sites. (A). Three constructs used include the ECR2 with a minimal promoter and either EGFP or mCherry. A third construct contains the ECR2 with five mutated Lef1/TCF sites as detailed in (B).