Abstract

Although sexual assault victimization has been shown to predict suicidality, little is known about the mechanisms linking these two factors. Using cross-sectional data (N = 6364) from the 2007 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, binge drinking significantly mediated the relationship between forced sexual intercourse and suicide for Hispanic (n = 1915) and Caucasian (n = 2928) adolescent females, but not for African American adolescent females (n = 1521). Results suggest the need for closer monitoring of adolescent victims of sexual assault who also abuse alcohol to intervene in early suicide behaviors. Treatment and intervention programs should also be culturally sensitive to account for differences in reaction to sexual trauma among race/ethnicity. Implications for suicide prevention and alcohol intervention strategies as well as suggestions to clinical providers are discussed.

Keywords: Adolescents, Sexual Assault, Alcohol, Suicide, Ethnicity

1. Introduction

Adolescent female sexual assault is a major public health problem. Eleven percent of high school girls report a history of being sexually assaulted (CDC, 2007), and over 50% report sexually coercive experiences (Struckman-Johnson et al., 2003). A majority (~ 60%) of female adolescent victims of sexual assault report that they were assaulted before age 18, with 25% reporting the first sexual assault before age 12, and 34% reporting the first sexual assault between the ages of 12-17 (CDC, 2008). The social, physical, and mental health consequences of being sexually assaulted are far reaching (Evans, Hawton & Rodham, 2004; Moncrieff & Farmer, 1998; Ullman & Brecklin, 2002). Beyond the trauma of the immediate event, victims often experience long-term problems such as increased sexual risk-taking, sexually transmitted diseases, unwanted pregnancies, depression, and post traumatic stress disorder (CDC, 2007; McFarlane et al., 2005).

McFarlane and colleagues (2005) found that adult female victims of sexual assault are more likely to consider and attempt suicide than their non-sexually abused counterparts. However, this does not appear to be a direct relationship as some victims of sexual assault do not develop suicidal tendencies (Cloitre, Scarvalone, & Difede, 1997). Thus, it is likely that certain risk and protective factors affect the likelihood of a sexual assault victim becoming suicidal (Swahn & Bossarte, 2007; Moncrieff & Farmer, 1998). Substance abuse, because of its independent association with both sexual assault and suicidal ideation, may help explain why some victims become suicidal while others do not. In particular, alcohol abuse is often comorbid with depression (McFarlane et al., 2005) and widely viewed as a precipitating factor for suicidal behaviors (Swahn & Bossarte, 2007). Furthermore, alcohol has been shown to increase aggression and impulsive behavior, both of which contribute to suicidality (Swahn & Bossarte, 2007). Binge drinking may put adolescents at risk for a wide range of health risk behaviors due to the depressant effects of alcohol and its impact on cognitive decision making abilities.

The purpose of this study was to examine whether binge drinking mediates the relationship between forced sexual intercourse and suicidality among a nationally representative sample of adolescent females. We also examined this relationship by race/ethnicity.

2. Methods

We analyzed data from the 2007 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), a nationally representative survey of United States high school students, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2008). The CDC conducts the survey bi-annually to track the incidence and prevalence of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality among high school students in grades 9 – 12. Schools were selected for participation with probability proportional to the size of student enrollment. Classes were then randomly selected for participation with all students eligible for voluntary participation. Questionnaires were completed anonymously by students during one class period after the local permission procedures were followed (CDC, 2008).

Responses from Hispanic (n = 1,915), Caucasian (n = 2,928), and African American (n = 1,521) females in grades 9 – 12 were examined.1 Because female sexual assault victims and male sexual assault victims may differ in their patterns of binge drinking and suicidal thinking, we chose to focus exclusively on females in this study. Forced sexual intercourse history was assessed by asking students the following yes/no question: “Have you ever been physically forced to have sexual intercourse when you did not want to?” The outcome variable, suicidality, was also measured by a single yes/no item: “During the past 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?” The proposed mediating variable, binge drinking, was assessed by asking students, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have 5 or more drinks of alcohol in a row, that is, within a couple of hours?” Responses were dichotomized as “yes/no” to having 5 or more drinks on one or more days during the past 30 days.

All analyses (e.g., descriptive, chi square, logistic regression, and mediational) were conducted using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS 16.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL.). Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess whether a lifetime history of forced sexual intercourse (yes/no) would predict suicidal behavior (yes/no) and whether this relationship was mediated by binge drinking (yes/no) for the entire sample. A Sobel test was conducted to test for mediation. Then, separate logistic regressions were used to examine if the relationship was the same for each subgroup (i.e., Hispanic, Caucasian, and African American).

3. Results

The mean age of girls in the overall sample was 16 (SD = 1.22) with a mean grade of 11th (SD = 1.11). Overall, 11% of adolescent females reported a lifetime history of forced sexual intercourse. African American girls (14.2%) were more likely than Hispanic (11.3%) or Caucasian (10.5%) girls to report a lifetime history of forced sexual intercourse (χ2 (2) = 13.33, p < .01). Nineteen percent of adolescent females had considered suicide in the past year, with Hispanics (21.5%) being more likely than their African American (18.2%) and Caucasian (18.2%) counterparts to report this behavior (χ2 (2) = 9.18, p < .05). Additionally, 23% of the adolescent females acknowledged binge drinking, with Hispanics (27.4%) and Caucasians (28.4%) more likely than African Americans (11.3%) to report binge drinking in the past 30 days (χ2 (2) = 171.42, p < .001).

3.1 Alcohol Abuse as a Mediator Between Sexual Assault and Suicidal Ideation

In meeting the requirements to test for mediation (Baron & Kenny, 1986), forced sexual intercourse was associated with suicidal ideation and binge drinking as shown in Table 1. Binge drinking was associated with suicidal ideation after controlling for forced sexual intercourse. The path from forced sexual intercourse to suicidal ideation was significantly reduced when accounting for binge drinking, suggesting that binge drinking partially mediated the relationship between forced sexual intercourse and suicidality.

Table 1.

Association of forced sexual intercourse, binge drinking, and suicidality for total population

| Model | B | SE | Wald χ2 | OR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal ideation | ||||||

| Forced sexual intercourse | 1.26 | .08 | 226.15 | 3.53 | 3.00, 4.16 | .000 |

| Binge drinking | ||||||

| Forced sexual intercourse | .74 | .08 | 76.83 | 2.09 | 1.77, 2.46 | .000 |

| Suicidal ideation1 | ||||||

| Forced sexual intercourse | .71 | .07 | 185.43 | 3.23 | 2.73, 3.83 | .000 |

| Binge drinking (Mediator) | 1.17 | .09 | 99.43 | 2.04 | 1.78, 2.35 | .000 |

Sobel test = 6.56, p < .01

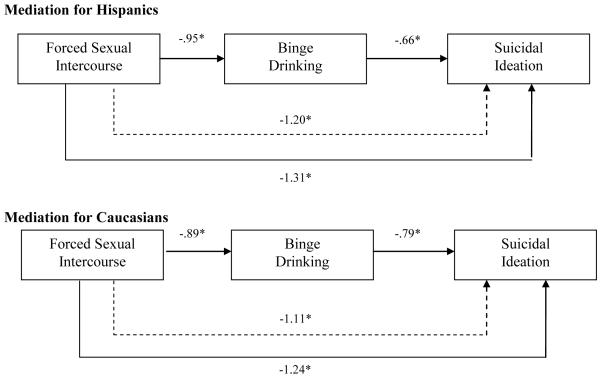

As depicted by Figure 1, similar results were found for Hispanic (Sobel test = 4.02, p < .001) and Caucasian girls (Sobel test = 5.29, p < .001). However, for African American girls, binge drinking did not mediate the relationship between forced sexual intercourse and suicidality (Sobel test = 1.69, p = .09).

Figure 1.

Mediation by race and ethnicity.

Mediational regression analyses of forced sexual intercourse and binge drinking on considering suicide among Hispanic and Caucasian females. Solid line between variables denotes direct paths between variables. Dotted lines indicate the path from forced sexual intercourse to suicidal ideation when forced sexual intercourse is mediated by binge drinking. Values listed are Beta weights.

* p < .001.

4. Discussion

Whereas previous studies have shown that an association between sexual assault and suicidal behavior exists (McFarlane et al., 2005; Moncrieff & Farmer, 1998), this study adds to the literature by utilizing a mediational model to examine the role that binge drinking may contribute to that relationship. The overall prevalence rates of binge drinking (28%), suicidal ideation (19%), and forced sexual intercourse (11%) found in our study are similar to those reported for these groups in previous studies (Chatterji, Dave, Kaestner & Markowitz, 2004; Waldrop, Hanson, Resnick, Kilpatrick, Naugle & Saunders 2007). We generally found that engaging in binge drinking could help explain why some victims of sexual assault become suicidal while others without a history of binge drinking do not. The finding is consistent with existing knowledge that victims of sexual abuse suffer from a multitude of negative psychological and social consequences, including the use and abuse of alcohol (McFarlane et al., 2005). The increases in aggression, impulsivity, and poor decision making that often accompany the misuse of alcohol may increase the risk of suicide in these individuals (Schilling, et al., 2009). One possible explanation for this is that sexual assault victims that do not abuse alcohol (a depressant) may cope in more adaptive ways and be less likely to ruminate about the previous sexual abuse, and thus less likely to have thoughts of suicide.

Interestingly, binge drinking did not mediate the relationship between forced sexual intercourse and suicidal ideation for African American females. Although African American girls were more likely than Hispanic and Caucasian girls to report a lifetime history of forced sexual intercourse, they were less likely than Hispanics or Caucasians to report engaging in binge drinking within the past 30 days. This finding is supported by previous research showing that African Americans, compared to Caucasians, are less likely to use alcohol before attempting suicide (Groves, Stanley, & Sher, 2007). Kung and colleagues (1998) researched whether the risk factors commonly associated with suicide (e.g., heavy alcohol use, use of mental services, and living arrangements) differed by race when adjusting for education and occupational status and found that only prior use of mental health services was associated with suicide for African Americans. Similar to our findings, they found no association between heavy alcohol use and suicide among African Americans. Social differences in the consumption of alcohol may also help explain the discrepancy. Specifically, African Americans report a lower proportion of alcohol consumption than Whites (Kung, et al., 1998) and are more likely to drink in outdoor, public places (Nyaronga, Greenfield, & McDaniel, 2009) which may be less conducive to suicidal thinking than drinking alone. Additional research is needed to explore these possibilities and to determine the mechanisms underlying the ethnic differences found in this study.

Primary limitations of our study result from the structure of the YRBS and have also been cited elsewhere (Chatterji et al., 2004). These limitations include: the use of self-report, single-item measures, minimal information about family context and demographic data, and the conservative definition of binge drinking in relation to females (i.e., the YRBS classifies binge drinking in females as five drinks within two hours instead of the commonly used four drinks within two hours). We also do not know the treatment history of the participants. It is likely that adolescents who received treatment for sexual assault respond differently to questions on substance abuse and suicide than assaulted adolescents who have not received treatment. In addition, because results were based on a lifetime history of forced sexual intercourse without an indication of the timing of the assault, it is possible that adolescents respond differently to being victimized in childhood versus adolescence. Further, specific details about the assault such as frequency, severity, and perpetrator identity were not available. Results likely differ for females raped by a dating partner versus those assaulted by a stranger or a family member. In addition, since the YRBS is only administered to adolescents attending school, our findings cannot be generalized to arguably the most at-risk population of children who are not in school (e.g., drop outs).

The cross-sectional nature of the YRBS dataset also limits the generalizability of these findings. Although we based our meditational analyses on the presumption that sexual assault preceded binge drinking and suicidality, our finding should be interpreted with caution as we cannot be certain of the directionality of the observed relationships. It could be that binge drinking precedes the sexual assault or that they co-occur. Further, since our study only looked at binge drinking, our findings may not generalize to adolescent female victims of forced sexual intercourse who abuse other substances. It is possible that additional mediators would have been identified had we examined the use of other substances. Finally, since this study did not include boys, the results are only generalizable to adolescent female victims of forced sexual intercourse. However, adolescent boys are also victims of sexual assault (Waldrop et al., 2007), and future research should focus on this population to examine if current findings generalize to male sexual assault victims.

Despite these limitations, these findings suggest that suicide prevention and intervention programs may benefit from addressing the drinking behaviors of female victims of sexual assault, particularly those of Hispanic and Caucasian backgrounds. Similarly, these findings suggest the need for alcohol treatment programs to give special consideration to binge drinking behaviors in adolescent victims of sexual assault. Moreover, programs should demonstrate cultural sensitivity, as race may influence victims’ cognitive and behavioral responses to sexual assault. Finally, health providers should be aware of the potentially higher risk of suicidal behavior among adolescent victims of sexual assault who also engage in binge drinking, and take proactive measures to ensure patient safety.

Acknowledgements

At the time this article was submitted, Dr. Behnken was a Kirschstein-NRSA postdoctoral fellow supported by an institutional training grant (T32HD055163) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD). She is currently a Lecturer at Iowa State University. Dr. Le is a Kirschstein-NRSA postdoctoral fellow supported by an institutional training grant (T32HD055163) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD). Dr. Temple is supported by a research career development award (K23HD059916) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. Dr. Berenson is supported by K24HD043659, NICHD. The authors thank James Northcutt for research assistance. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kenney Shriver NICHD or the NIH.

Footnotes

The category of Hispanic was based upon student self-report of Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. Race was determined by students who did not report Hispanic ethnicity, but self-identified as either African American or Caucasian.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baron R, Kenny D. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Accessed on September 2, 2008];2007 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Available at: www.cdc.gov/yrbss.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Understanding Sexual Violence: Fact Sheet. 2009 April 7; Retrieved. from http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/sexualviolence/index.html.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Violence Prevention. Sexual Violence: Facts at a glance. 2009 April 7; Retrieved. from http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/suicide/riskprotectivefactors.html.

- Chatterji P, Dave D, Kaestner R, Markowitz S. Alcohol abuse and suicide attempts among youth. Economics & Human Biology. 2004;2:159–180. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre M, Scarvalone P, Difede J. Posttraumatic stress disorder, self- and interpersonal dysfunction among sexually retraumatized women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1997;10:437–452. doi: 10.1023/a:1024893305226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans E, Hawton K, Rodham K. Factors associated with suicidal phenomena in adolescents: a systematic review of population-based studies. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:957–979. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves S, Stanley BH, Sher L. Ethnicity and the relationship between adolescent alcohol use and suicidal behavior. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health. 2007;19:19–25. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2007.19.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung H-C, Liu X, Juon H-S. Risk factors for suicide in Caucasians and in African-Americans: a matched case-control study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1998;33:155–161. doi: 10.1007/s001270050038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane J, Malecha A, Gist J, Watson K, Batten E, Hall I, Smith S. Intimate partner sexual assault against women and associated victim substance use, suicidality, and risk factors for femicide. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2005;26:953–967. doi: 10.1080/01612840500248262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncrieff J, Farmer R. Sexual abuse and the subsequent development of alcohol problems. Alcohol & Alcoholism. 1998;33:592–601. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/33.6.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyaronga D, Greenfield TK, McDaniel PA. Drinking context and drinking problems among Black, White, and Hispanic men and women in the 1984, 1995, and 2005 U.S. national alcohol surveys. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:16–26. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling EA, Aseltine RH, Glanovsky JL, James A, Jacobs D. Adolescent alcohol use, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;44:335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struckman-Johnson C, Struckman-Johnson D, Anderson PB. Tactics of sexual coercion: When men and women won’t take no for an answer. Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40:76–86. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swahn MH, Bossarte RM. Gender, early alcohol use, and suicide ideation and attempts: Findings from the 2005 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;41:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman SE, Brecklin LR. Sexual assault history and suicidal behavior in a national sample of women. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior. 2002;32:117–130. doi: 10.1521/suli.32.2.117.24398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop AE, Hanson RF, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Naugle AE, Saunders BE. Risk factors for suicidal behaviors among a national sample of adolescents: implications for prevention. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:869–879. doi: 10.1002/jts.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]