Abstract

Intradialytic hypertension, defined as an increase in blood pressure during or immediately after hemodialysis which results in postdialysis hypertension, has long been recognized to complicate the hemodialysis procedure, yet it is often largely ignored. In light of recent investigations which have suggested intradialytic hypertension is associated with adverse outcomes, this review will broadly cover the epidemiology, prognostic significance, potential pathogenic mechanisms, prevention, and possible treatment of intradialytic hypertension. Intradialytic hypertension affects up to 15% of hemodialysis patients and occurs more frequently in patients who are older, have lower dry weights, are prescribed more antihypertensive medications, and have lower serum creatinine. Recent studies have demonstrated intradialytic hypertension to be independently associated with higher hospitalization rates and decreased survival. While the pathophysiology of intradialytic hypertension is uncertain, it is likely multifactorial and includes subclinical volume overload, sympathetic overactivity, activation of the renin angiotensin system, endothelial cell dysfunction, and specific dialytic techniques. Prevention and treatment of intradialytic hypertension may include careful attention to dry weight, avoidance of dialyzable antihypertensive medications, limiting the use of high calcium dialysate, achieving adequate sodium solute removal during hemodialysis, and using medications which inhibit the rennin-angiotensin-aldosterone system or which lower endothelin 1. In summary, while intradialytic hypertension is often underappreciated, recent studies suggest it should not be ignored. However, further work is necessary to elucidate the pathophysiology of intradialytic hypertension and its appropriate management, and to determine whether treatment of intradialytic hypertension can improve clinical outcomes.

Epidemiology of Intradialytic Hypertension

Definition

While hemodialysis lowers blood pressure (BP) in most hypertensive end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients, some patients exhibit a paradoxical increase in BP during hemodialysis. This increase in BP during hemodialysis, termed intradialytic hypertension, has been recognized for many decades (1, 2). However, no standard definition of intradialytic hypertension exists, it is often under recognized, the pathophysiology is poorly understood, and the clinical consequences have only recently been investigated.(3–7) While under-investigated, prior clinical studies have defined intradialytic hypertension in the following ways:

an increase in mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) ≥ 15 mmHg during or immediately after hemodialysis,(8)

an increase in systolic BP (SBP) >10 mmHg from pre to postdialysis,(4, 5)

hypertension during the second or third hour of hemodialysis after significant ultrafiltration has taken place,(2)

an increase in BP that is resistant to ultrafiltration,(1, 9, 10)

aggravation of pre-existing hypertension or development of de novo hypertension with erythropoietin stimulating agents.(11)

As a unifying criteria for the diagnosis of intradialytic hypertension has not been proposed, the focus of this review will be on BP which increases during or immediately after hemodialysis and results in postdialysis hypertension (defined by the National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative [KDOQI] as a postdialysis BP ≥130/80 mmHg).

Prevalence

Though no common definition of intradialytic hypertension exists, the occurrence of an increase in BP pre to postdialysis has been identified in up to 15% of maintenance hemodialysis patients. In our retrospective analysis of 438 prevalent hemodialysis participants enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of blood volume monitoring (Crit-Line Intradialytic Monitoring Benefit [CLIMB] study),(12) 13.2% of participants exhibited an increase in SBP of more than 10 mmHg from pre to postdialysis.(4) In a separate analysis of 1,748 incident hemodialysis patients enrolled in the USRDS Dialysis Morbidity and Mortality Wave II cohort, 12% exhibited >10 mmHg increases in SBP pre to postdialysis.(5) Another author noted that 5–15% of hemodialysis patients have hypertension resistant to ultrafiltration (8) and one survey of hemodialysis patients noted 8% of treatments over a 2-week period were associated with an increase in MAP >15 mmHg during or immediately after hemodialysis.(10) While intradialytic increases in BP typically lead to postdialysis hypertension, the occurrence of intradialytic increases in BP may also be present in patients without hypertension. In our cohort of prevalent hemodialysis participants in CLIMB, 94% of participants with >10 mmHg intradialytic increases in SBP exhibited postdialysis hypertension (unpublished data). Similarly, 93% of incident USRDS Wave 2 patients with >10 mmHg intradialytic increases in SBP exhibited postdialysis hypertension (unpublished data). Therefore, intradialytic increases in BP are relatively common and typically result in postdialysis hypertension.

Clinical characteristics

Clinical characteristics identifying patients who exhibit intradialytic hypertension have recently been described. In our investigation, we compared participants whose SBP rose >10 mmHg on average over 3 hemodialysis (HD) sessions to participants whose SBP was unchanged with HD (−10 mmHg to 10 mmHg) or whose SBP decreased at least 10 mmHg with HD.(4) On average, participants with intradialytic hypertension (compared to those without) increased their SBP +19 mmHg with HD, they were older, they had lower dry weights, they were prescribed a greater number of antihypertensive medications, and they had lower serum creatinine. In a separate analysis of 32,295 hemodialysis sessions, patients who were older or African American were more likely to exhibit an increase in SBP pre to postdialysis, despite similar amounts of ultrafiltration.(13) Among 1,748 incident hemodialysis patients, patients with >10 mmHg intradialytic increases in SBP had lower dry weights, lower interdialytic weight gain, they were prescribed a greater number of antihypertensive medications, and they had lower serum albumin when compared to patients without intradialytic SBP increases.(5) In summary, intradialytic hypertension appears to occur more commonly in older patients, in patients with lower body weight and in those with either lower serum creatinine or serum albumin. In addition, patients who exhibit intradialytic hypertension appear to be prescribed more antihypertensive medications, but the role of specific agents remains to be determined.

Prognostic significance

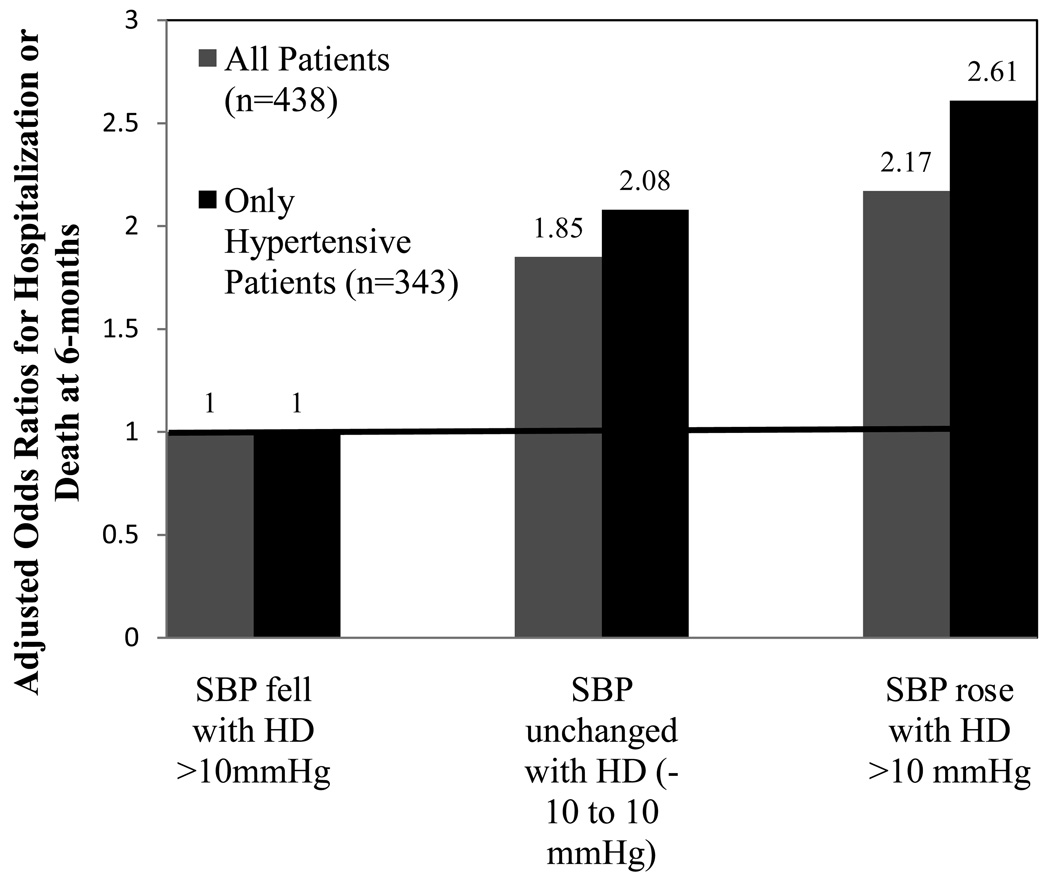

Recent investigations into the prognostic significance of intradialytic BP changes have identified intradialytic hypertension to be associated with adverse clinical outcomes. In our secondary analysis of 438 participants in CLIMB, participants whose SBP rose with hemodialysis or whose SBP failed to lower from pre to postdialysis, had a 2-fold adjusted increased odds of hospitalization or death at 6-months compared to participants whose SBP fell with hemodialysis (Figure 1).(4) When the cohort was restricted to participants with KDOQI defined hypertension,(14) the differences in clinical outcomes were even more striking. Hypertension affected 79% of all participants and of those with hypertension, those whose SBP increased with HD had a 2.6 fold increased odds of hospitalization or death at 6-months compared to participants whose SBP declined with HD (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Adjusted 6-month odds ratio of non-access related hospitalization or death among 438 prevalent end-stage renal disesase participants categorized by systolic blood pressure (SBP) changes with hemodialysis (HD).

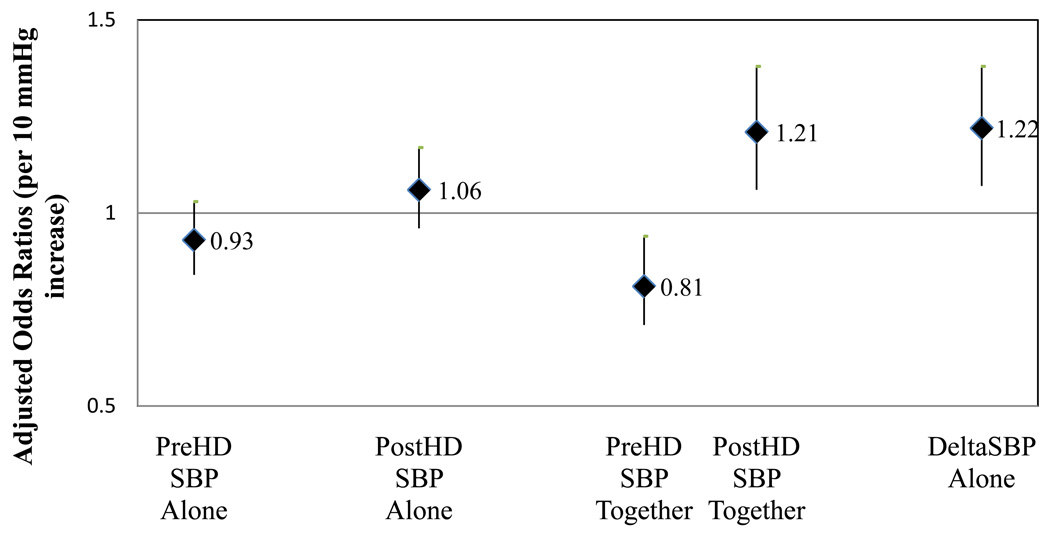

While some studies have identified predialysis SBP to have an inverse association with mortality,(15, 16) an increased postdialysis SBP has been noted in other investigations to be associated with adverse outcomes.(17) In our analyses, neither pre nor postdialysis SBP tested alone were predictive of clinical outcomes; however, models including both pre and postdialysis SBP together demonstrated adverse outcomes associated with a lower predialysis SBP and higher postdialysis SBP (Figure 2). In models including change in SBP pre to postdialysis (deltaSBP), every 10 mmHg increase in SBP with HD was associated with an adjusted 22% increased odds of hospitalization or death at 6-months.(4)

Figure 2.

Adjusted 6-month odds ratio (95% confidence interval) for non-access related hospitalization or death associated with 1) predialysis systolic blood pressure (SBP) (per 10 mmHg increase) when tested alone, 2) postdialysis SBP (per 10 mmHg increase) when tested alone, 3) pre and postdialysis SBP when tested together (per 10 mmHg increase in each), and 4) SBP change with hemodialysis (HD) (per 10 mmHg increase)

Similarly, in our analysis of 1,748 incident USRDS hemodialysis patients, there was an adjusted 6% increased hazard of death at 2-years associated with every 10 mmHg increase in SBP during HD.(5) However, the greatest hazard of death associated with increasing SBP during HD was found in patients with low predialysis SBP (<120 mmHg). Thus, in incident hemodialysis patients without predialysis hypertension, intradialytic increases in SBP may be less of a cardiovascular risk factor and more of a marker of a sicker patient population.

Hemodynamic Profile Associated with Intradialytic Hypertension

It is well recognized that dialysis-unit obtained BP parameters can be poor reflections of the interdialytic hemodynamic burden a patient experiences.(18, 19) Whether patients whose BP increases during hemodialysis experience an overall higher interdialytic hemodynamic burden compared to those whose BP declines during HD is uncertain. In one study analyzing the predictive power of pre and postdialysis unit BP measurements compared to ambulatory blood pressure, patients with intradialytic increases in SBP (~20 mmHg) were noted to exhibit a poor correlation between dialysis-unit obtained BP parameters and ambulatory blood pressure.(20) In patients with intradialytic hypertension, predialysis SBP had a correlation coefficient of 0.26 with ambulatory blood pressure and postdialysis BP had a correlation coefficient of 0.59 with BP measured by ambulatory blood pressure. Thus, while it is evident that the low predialysis SBP in patients with intradialytic hypertension is not reflective of the interdialytic BP, whether the elevated postdialysis SBP is an accurate reflection of the interdialytic hemodynamic burden is uncertain.

Although the interdialytic BP burden of intradialytic hypertension remains to be determined, prior studies have investigated the intradialytic hemodynamic profile in patients with intradialytic hypertension. BP is equal to cardiac output×peripheral vascular resistance, so the increase in BP occurring during HD must be due to either increased cardiac output or increased peripheral vascular resistance (PVR); separate studies suggest both factors may contribute to intradialytic hypertension.(6, 21–23) In an investigation of 19 patients, Boon et al compared stroke volume, cardiac index and PVR among patients whose SBP declined during HD (~25 mmHg) in response to ultrafiltration and patients whose SBP increased during HD (~ +5 mmHg), despite similar changes in blood volume. It was noted that while PVR increased similarly between the 2 groups, stroke volume and cardiac output declined less among patients with dialysis-unresponsive BP.(22) In a separate investigation of 15 patients (5 whose BP were unchanged with HD compared to 10 whose BP declined with HD), there was no difference in ultrafiltration volume or cardiac output between groups, but PVR rose significantly in patients whose BP did not decrease with HD.(23) More recently, Chou et al compared echocardiography pre and postdialysis in a study of 30 patients with intradialytic hypertension (defined as a MAP increase >15 mmHg during HD) and 30 control patients. In this study, the change in cardiac output pre to postdialysis was similar between groups; however PVR increased 57% in patients with intradialytic hypertension compared to 17.7% in control patients.(6)

Pathogenesis of Intradialytic Hypertension

Overview

While the mechanism and pathophysiology of intradialytic hypotension has been extensively investigated, its pathogenesis remains to be determined. Numerous factors have been suggested to contribute and are listed in Box 1. Each of these possible factors may contribute to the development of intradialytic hypertension in select patients and will be discussed in more detail.

Box 1. Potential Pathophysiologic Mechanisms of Intradialytic Hypertension.

Volume overload

Sympathetic over-activity

Activation of the renin-angiotensin aldosterone system

Endothelial cell dysfunction

-

Dialysis-specific factors

net sodium gain

high ionized calcium

hypokalemia

-

Medications

Erythropoietin stimulating agents

Removal of antihypertensive medications

Vascular stiffness

Volume

Volume overload plays a significant role in poorly controlled BP in hemodialysis patients. Prior investigations of intradialytic hypertension have suggested volume overload may be a key contributor to its pathogenesis. Cirit and colleagues investigated 7 patients who exhibited significant cardiac dilation on echocardiography and had BP elevations with hemodialysis which were not responsive to antihypertensive medications. Following intense ultrafiltration and lowering of dry weight, the echocardiographic volume parameters improved and the BP response to hemodialysis normalized in most patients.(9) Another study of 6 patients with intradialytic hypertension noted that modest ultrafiltration resulted in increased cardiac output and elevations in MAP.(21) More aggressive ultrafiltration in these patients resulted in a lowering of cardiac index and MAP, suggesting significant volume overloaded as the cause of the initial increase in MAP with hemodialysis and ultrafiltration. However, in another investigation, neither echo-specific volume overload nor cardiac dysfunction were identified in patients with intradialytic hypertension compared to controls.(6) Therefore, while select subsets of patients with hypervolemia may exhibit intradialytic hypertension, volume overload does not solely explain the pathophysiology of BP elevations with hemodialysis in all patients.

Sympathetic over-activity

intradialytic hypertension is caused by an increase in stroke volume and/or vasoconstriction with an inappropriate elevation in PVR during hemodialysis; therefore, it appears plausible that stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system should contribute its development. Further, it is well recognized that hemodialysis patients have excess sympathetic nervous activity as measured by microneurography.(24, 25) However, in an investigation by Chou et al, there was neither an increase in plasma epinephrine nor plasma norepinephrine during hemodialysis to explain the increase in PVR among patients with intradialytic hypertension.(6) However, circulating levels of catecholamines do not always correlate with BP changes and differences in microneurography among patients with and without intradialytic hypertension have not been performed.

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

Alternative explanations for intradialytic hypertension include excess stimulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) associated with intravascular volume reduction. However, individual responses to volume removal and activation of RAAS are not consistent. In 2 separate investigations, individual BP responses to hemodialysis and ultrafiltration were not related to blood volume changes during hemodialysis as the percent change in blood volume was similar between participants with and without hemodialysis-responsive BP.(22, 23) However, in a study of 30 patients with intradialytic hypertension compared to 30 controls, the percent increase in blood volume (determined by change in hematocrit) was lower in patients with intradialytic hypertension despite similar ultrafiltration volumes and rates of fluid removal.(6)

In support of the hypothesis that intradialytic hypertension may be mediated by the RAAS, one interventional study of 6 patients with intradialytic hypertension evaluated whether treatment with an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor (captopril) improved BP control during hemodialysis.(26) Plasma renin increased in 4/6 patients and the administration of 50 mg captopril prior to hemodialysis improved BP control in those with and without elevated plasma renin levels. On the other hand, the study by Chou et al found no increase in plasma renin pre to postdialysis in patients with intradialytic hypertension.(6)

Endothelin 1

More recent investigations have suggested endothelial cell dysfunction may play a significant role in hemodynamic changes during HD.(6, 7, 27) In response to ultrafiltration, mechanical and hormonal stimuli, the endothelial cells synthesize and release humoral factors which contribute to BP homeostasis. Imbalances in endothelial-derived hormones, such as nitric oxide (NO; a smooth muscle vasodilator) and endothelin 1 (a vasoconstrictor), can lead to hypotension or hypertension during HD. To date, 3 studies have investigated balances in endothelial-derived factors in patients with intradialytic hypertension.

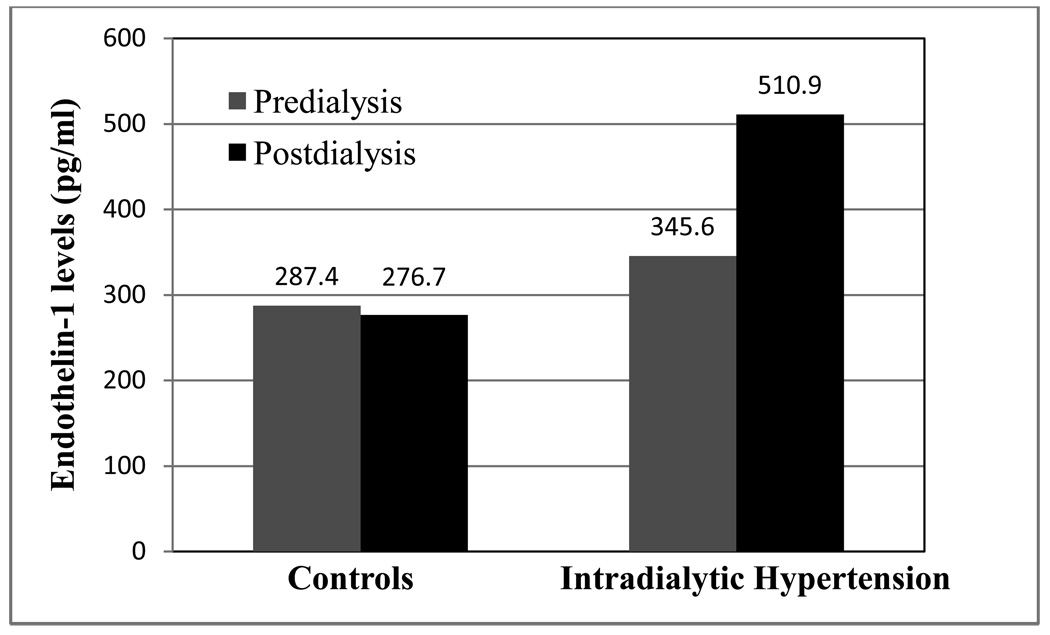

In an investigation of 27 patients (9 with intradialytic hypertension, 9 with intradialytic hypotension and 9 with stable intradialytic BP), the authors compared pre and postdialysis levels of fractional exhaled nitric oxide (NO), l-arginine, serum nitrite/nitrate, asymmetric dimethyl arginine (ADMA), and endothelin 1 (ET1, encoded by the EDN1 gene).(7) Predialysis fractional exhaled NO was lowest in patients whose BP did not change or rose with HD compared to those with intradialytic hypotension. There was no significant difference in l-arginine, nitrite/nitrate or ADMA between groups, but ET1 increased pre to postdialysis in the 9 patients with intradialytic hypertension. In a larger study of 60 patients with and without intradialytic hypertension, Chou et al also identified imbalances in endothelial-derived BP regulators.(6) Patients with intradialytic hypertension exhibited a significant increase in ET1 pre to postdialysis compared to patients without intradialytic hypertension (Figure 3). Further the balance between NO and ET1 (NO/ET1 ratio), while depressed in both groups postdialysis, was significantly lower in patients with intradialytic hypertension. Similarly, El-Shafey and colleagues, in a study of 45 hemodialysis patients, noted pre to postdialysis ET1 levels increased in patients with intradialytic hypertension, decreased in patients with intradialytic hypotension and remained unchanged in patients whose BP did not change during HD. (28) Thus, these 3 studies suggest intradialytic hypertension may be caused by abnormal endothelial cell response to hemodialysis resulting in inappropriately low NO and excess ET1.

Figure 3.

Comparison of pre and postdialysis endothelin-1 levels between 30 patients without intradialytic hypertension and 30 patients with intradialytic hypertension

Medications

Removal of antihypertensive medications

The dialysis procedure removes a number of antihypertensive medications and clearly removal of antihypertensive medications could precipitate intradialytic hypertension. Particular antihypertensive agents, such as ACE inhibitors (with the exception of fosinopril) and beta-blockers (atenolol and metoprolol) are removed by dialysis (Table 1).(29) While removal of antihypertensive agents during HD should be considered in any patient with intradialytic hypertension, it has not been investigated whether this plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of intradialytic hypertension and a prior study demonstrated intradialytic hypertension occurred in patients off antihypertensive agents.(6)

Table 1.

Percent Removal of commonly prescribed antihypertensive agents during hemodialysis

| Agent | Percent Removal |

|---|---|

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | |

| Benazepril | <30% |

| Enalapril | 35% |

| Fosinopril | 2% |

| Lisinopril | 50% |

| Ramipril | <30% |

| Beta-Blockers | |

| Atenolol | 75% |

| Carvedilol | None |

| Labetalol | <1 |

| Metoprolol | High |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | |

| Losartan | None |

| Candesartan | None |

| Eprosartan | None |

| Telmisartan | None |

| Valsartan | None |

| Irbesartan | None |

| Calcium channel blockers | |

| Amlodipine | None |

| Diltiazem | <30% |

| Nifedipine | Low |

| Nicardipine | ? |

| Felodipine | No |

| Verapamil | Low |

| Other | |

| Clonidine | 5% |

| Hydralazine | None |

| Minoxidil | Yes |

Source: National Kidney Foundation's K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients (29)

Erythropoietin stimulating agents (ESAs)

The use of ESAs is associated with increased BP in hemodialysis patients.(30, 31) In a small investigation of the acute effects of ESAs in hemodialysis patients, within 30 minutes following intravenous ESA, there was a significant increase in ET1 and a concomitant rise in MAP which was not demonstrated in patients given subcutaneous ESA or placebo. In addition, 53% (10/19) of patients in this study given intravenous ESA had an increase in MAP >10 mmHg in the interdialytic period. Thus, if ESA is given intravenous prior to the end of hemodialysis, it is possible this may contribute to the pathogenesis of intradialytic hypertension in susceptible patients.

Dialysis-specific factors

Sodium

Hypernatric dialysate has been used to help maintain hemodynamic stability during hemodialysis, but it can result in a positive sodium balance with concomitant increased thirst, increased interdialytic weight gain, net weight gain, and interdialytic hypertension.(32) In a prospective crossover study comparing different sodium dialysate profiles in 11 patients, higher time-averaged sodium dialysate concentrations of 147 mEq/L (compared to 138 or 140 mEq/L) during hemodialysis resulted in higher 24-hour ambulatory SBP (up to 10 mmHg), diastolic BP, and BP load.(33) In addition, the use of standard sodium dialysate (such as 140 mEq/L) in a patient with a predialysis sodium <140 mEq/L will result in an intradialytic sodium load which could contribute to intradialytic hypertension. However, while inadequate sodium solute removal may contribute to poorer overall BP control, no study has tested the role of dialysate sodium concentration in the development of intradialytic hypertension.

Potassium

Low serum potassium can have a direct vasoconstrictor effect but the role of dialysate potassium in intradialytic BP is uncertain. In a small investigation of 11 hemodialysis patients, Dolson et al analyzed the effects of 3 different dialysate potassium concentrations (1, 2 and 3 mmol/L) on BP predialysis, BP immediately postdialysis and BP 1 hour after hemodialysis. BP declined during hemodialysis with all dialysate potassium concentrations, however BP significantly increased 1 hour postdialysis in patients treated with 1 mEq/L and 2 mEq/L potassium dialysate.(34) While this study suggests hypokalemia induced by low potassium dialysate may cause rebound hypertension following hemodialysis, it is unlikely that low potassium dialysate plays a significant role in intradialytic hypertension as prior investigations identified intradialytic hypertension in patients regardless of the prescribed potassium baths.(6, 7)

Calcium

It is well established that an acute increase in ionized calcium increases myocardial contractility, increases cardiac output, and can improve hemodynamic instability during hemodialysis. (35–38) In a few small studies, high calcium dialysate has been used to improve hemodynamic instability in hypotensive prone patients and/or patients with impaired cardiac function.(39–41) High calcium dialysate has also been noted to decrease arterial compliance, increase arterial stiffness and result in less of a decline in SBP during HD.(41–43) While increasing dialysate calcium can stabilize BP during hemodialysis, the role of high calcium dialysate in the pathophysiology of intradialytic hypertension has not been fully investigated and patients have been demonstrated to exhibit intradialytic hypertension on standard calcium dialysate.(6)

Arterial stiffness

Arterial stiffness, as measured by pulse wave velocity, has been associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes in hemodialysis patients.(44, 45) In a cohort of 47 hemodialysis patients without known cardiovascular disease, Mourad et al compared pulse wave velocity between patients with hemodialysis-responsive BP (defined as a decrease in MAP>5% during hemodialysis) and hemodialysis-unresponsive BP (defined as a failure to decrease MAP>5% during hemodialysis). Forty-five percent of patients were classified as having HD-responsive BP with a 17% fall in MAP with hemodialysis compared to a 6% increase in MAP in the HD-unresponsive group. Pulse wave velocity was higher in patients with HD-unresponsive BP (12.9 vs. 10.8 m/s), suggesting unrecognized arteriosclerosis to either contribute to the occurrence of intradialytic hypertension or to be its consequence.(46)

Prevention of Intradialytic Hypertension

As numerous factors may contribute to the development of intradialytic hypertension, a number of options are available to try to prevent its occurrence. Patients with lower serum creatinine, lower dry weights and lower serum albumin have been demonstrated to be more likely to have intradialytic hypertension and this may partially be related to inappropriate estimation of dry weight in these patients. Thus, vigilance and attention should be paid to changes in a patient’s oral intake and nutritional status to ensure patients are at their ideal dry weight. Second, dosing of antihypertensive medications should be tailored to individual patients. Routine withholding of BP medications prior to hemodialysis should be avoided unless the patient has intradialytic hypotension. In addition, the use of antihypertensive agents which are not dialyzed should be preferred (see Table 1). Third, the dialysis prescription should be individualized to achieve adequate sodium solute removal and the routine use of high calcium dialysate should be avoided unless clinically indicated. Finally, while the role of ESA agents in intradialytic hypertension is unclear, the lowest possible dose necessary should be used and in patients with evidence of intradialytic hypertension, subcutaneous dosing should be considered.

Treatment of Intradialytic Hypertension

In patients who develop intradialytic hypertension, consideration should be paid to the possible causes (Box 1). In certain instances, the trigger is clear; such as a patient who has missed a few dialysis treatments, is above their dry weight and develops intradialytic hypertension. After a few treatment sessions and a return to their normal dry weight, the intradialytic hypertension usually resolves. In other patients, the etiology and treatment may not be forthright and the following therapeutic options should be considered in hypertensive patients with intradialytic hypertension.

Volume management

In light of 2 small studies demonstrated improvement in intradialytic hypertension with lowering of dry weight over time in select individuals,(9, 21) an attempt to reduce dry weight should be performed in patients with intradialytic hypertension. Further, patients should be instructed to minimize salt and fluid intake between hemodialysis sessions. However, while lowering of dry weight may improve intradialytic hypertension in some patients; this is unlikely to resolve the condition in all instances.

Inhibition of the sympathetic nervous system

The role of sympathetic over-activity in intradialytic hypertension has not been firmly established. It is clear that patients with renal disease have evidence of sympathetic nerve activity, which normalizes after nephrectomy.(24) Whether patients who have undergone bilateral nephrectomy develop intradialytic hypertension is unknown but this certainly cannot be routinely advocated to control BP. Adrenergic blockers such as alpha- and beta-blockers should be considered as therapeutic options to control BP. In particular, carvedilol and labetolol with combined alpha and beta-adrenergic blockade should be considered as they are not significantly removed by hemodialysis.

Inhibition of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

Activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system with ultrafiltration during HD may contribute to intradialytic hypertension and inhibition of RAAS can serve as a therapeutic option. In a small study of 6 patients with intradialytic hypertensive crisis, administration of captopril was beneficial in controlling BP.(26) Newer longer-acting ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers may improve intradialytic hypertension particularly since certain RAAS inhibitors can inhibit ET1 release,(47) however this has not been investigated to date.

Pharmacologic inhibition of endothelin 1

Three investigations have demonstrated elevated postdialysis levels of ET1 in patients with intradialytic hypertension; however it is unknown whether pharmacologic inhibition of ET1 can abolish intradialytic hypertension. Specific ET1 antagonists (such as avosentan) may be effective if they can be demonstrated to be safe in hemodialysis populations. Alternatively, nonspecific ET1 inhibitors (such as RAAS inhibition or carvedilol) could potentially improve intradialytic hypertension by inhibiting ET1 release.(47–49) One ongoing pilot study (NCT00827775 [www.ClinicalTrials.gov]) is testing the efficacy of carvedilol as treatment for intradialytic hypertension and endothelial cell dysfunction.

Antihypertensive regimen

Class of antihypertensive agents, timing and dosing should be reviewed when patients have intradialytic hypertension. As certain ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers are removed by dialysis; these medications should be changed to non-dialyzed antihypertensives. Patients should also be instructed not to withhold BP medications prior to hemodialysis. As mentioned, administration of captopril has been shown to improve intradialytic hypertensive crisis, however considering this medication is short-acting and removed by dialysis, alternative agents may be preferred.(26)

ESAs

As previously reviewed, intravenous administration of ESAs can raise BP in certain individuals. In patients with intradialytic hypertension, discussions with the patient regarding switching from intravenous to subcutaneous ESA should occur, particularly if the patient requires large ESA doses.

Adjustment of the dialysis prescription

Inadequate sodium solute removal can result in excess fluid intake and hypertension; therefore dialysis prescriptions should be tailored to achieve a net negative sodium solute balance. Prescriptions which have a programmed variable sodium dialysate have been shown to minimize sodium solute loading during hemodialysis and can result in lower postdialysis BP, particularly in patients with serum sodium <140 mEq/L who may receive a sodium load with the use of standard sodium dialysate.(50) Second, high calcium dialysate increases cardiac contractility and cardiac output which could exacerbate hypertension during hemodialysis; therefore, high calcium dialysate should be avoided in patients with intradialytic hypertension. Other changes to the dialysis prescription which may improve the condition include longer duration of hemodialysis, more frequent hemodialysis, and or nocturnal hemodialysis. These alternative dialytic modalities have been demonstrated to improve BP control (51, 52) and potentially endothelial cell dysfunction (53); therefore, while they have not been specifically investigated, they should be considered in patients with refractory, difficult to treat intradialytic hypertension.

Conclusion

intradialytic hypertension has been a long-recognized phenomenon; however only recent investigations have begun to describe its epidemiology and the underlying pathophysiology, and to unveil its association with adverse clinical outcomes. While no consensus definition exists, a consistent increase in BP during hemodialysis which results in an elevated postdialysis BP (>130/80 mmHg) should be considered intradialytic hypertension. intradialytic hypertension is present in up to 15% of hemodialysis patients and is more common in patients who are older, have lower dry weights and are prescribed more antihypertensive medications. In hypertensive patients, intradialytic hypertension is independently associated with over a 2.5-fold increased risk of hospitalization or death at 6-months. As the underlying pathophysiology is likely multifactorial, treatment of intradialytic hypertension should be individualized to the patient and includes lowering of dry weight, changing to nondialyzable antihypertensive medications which inhibit RAAS or lower ET1, considering switching from intravenous to subcutaneous ESA, and altering the dialysis prescription. Future studies determining how to manage intradialytic hypertension should test the efficacy of these therapeutic interventions and larger studies are required to determine whether treatment can improve clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Dr. Uptal Patel for his critical review of this manuscript.

Support: Dr. Inrig was supported by National Institutes of Health grant K23 HL092297.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: None.

References

- 1.Levin NW. Intradialytic hypertension: I. Semin Dial. 1993;6:370–371. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fellner SK. Intradialytic hypertension: II. Semin Dial. 1993;6:371–373. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen J, Gul A, Sarnak MJ. Management of intradialytic hypertension: the ongoing challenge. Semin Dial. 2006;19:141–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2006.00140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inrig JK, Oddone EZ, Hasselblad V, et al. Association of intradialytic blood pressure changes with hospitalization and mortality rates in prevalent ESRD patients. Kidney Int. 2007;71:454–461. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inrig JK, Patel UD, Toto R, Szczech LA. Association of Blood Pressure Increases during Hemodialysis with 2-year Mortality in Incident Hemodialysis Patients: A Secondary Analysis of the Dialysis Morbidity and Mortality Wave 2 Study. AJKD. 2009 doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou KJ, Lee PT, Chen CL, et al. Physiological changes during hemodialysis in patients with intradialysis hypertension. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1833–1838. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raj DS, Vincent B, Simpson K, et al. Hemodynamic changes during hemodialysis: role of nitric oxide and endothelin. Kidney Int. 2002;61:697–704. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amerling RCG, Dubrow A, Levin NW, Osheroff R, editors. Complications during hemodialysis. Stamford, CT: Appleton and Lange; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cirit M, Akcicek F, Terzioglu E, et al. Paradoxical rise in blood pressure during ultrafiltration in dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1995;10:1417–1420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mees D. Rise in blood pressure during hemodialysis-ultrafiltration: a "paradoxical" phenomenon? Int J Artif Organs. 1996;19:569–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarkar SR, Kaitwatcharachai C, Levin NW, editors. Complications during hemodialysis. McGraw-Hill Professional; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reddan DN, Szczech LA, Hasselblad V, et al. Intradialytic blood volume monitoring in ambulatory hemodialysis patients: a randomized trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2162–2169. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004121053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inrig JK, Patel UD, Gillespie BS, et al. Relationship between interdialytic weight gain and blood pressure among prevalent hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50:108–118. 118, e101–e104. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines on Hypertension and Antihypertensive Agents in Chronic Kidney Disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 43 suppl 1:S1–S290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stidley CA, Hunt WC, Tentori F, et al. Changing relationship of blood pressure with mortality over time among hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:513–520. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004110921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Z, Lacson E, Jr, Lowrie EG, et al. The epidemiology of systolic blood pressure and death risk in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48:606–615. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zager PG, Nikolic J, Brown RH, et al. U curve association of blood pressure and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1998;54:561–569. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahman M, Griffin V, Kumar A, Manzoor F, Wright JT, Jr, Smith MC. A comparison of standardized versus "usual" blood pressure measurements in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:1226–1230. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.33395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agarwal R, Peixoto AJ, Santos SFF, Zoccali C. Pre- and Postdialysis Blood Pressures Are Imprecise Estimates of Interdialytic Ambulatory Blood Pressure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:389–398. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01891105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mendes RB, Santos SF, Dorigo D, et al. The use of peridialysis blood pressure and intradialytic blood pressure changes in the prediction of interdialytic blood pressure in haemodialysis patients. Blood Press Monit. 2003;8:243–248. doi: 10.1097/00126097-200312000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gunal AI, Karaca I, Celiker H, Ilkay E, Duman S. Paradoxical rise in blood pressure during ultrafiltration is caused by increased cardiac output. Journal of Nephrology. 2002;15:42–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boon D, van Montfrans GA, Koopman MG, Krediet RT, Bos WJ. Blood pressure response to uncomplicated hemodialysis: the importance of changes in stroke volume. Nephron Clin Pract. 2004;96:c82–c87. doi: 10.1159/000076745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaignon M, Chen WT, Tarazi RC, Nakamoto S, Bravo EL. Blood pressure response to hemodialysis. Hypertension. 1981;3:333–339. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.3.3.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Converse RL, Jr, Jacobsen TN, Toto RD, et al. Sympathetic overactivity in patients with chronic renal failure. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1912–1918. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212313272704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park J, Campese VM, Nobakht N, Middlekauff HR. Differential distribution of muscle and skin sympathetic nerve activity in patients with end-stage renal disease. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1873–1876. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90849.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bazzato G, Coli U, Landini S, et al. Prevention of intra- and postdialytic hypertensive crises by captopril. Contrib Nephrol. 1984;41:292–298. doi: 10.1159/000429299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erkan E, Devarajan P, Kaskel F. Role of nitric oxide, endothelin-1, and inflammatory cytokines in blood pressure regulation in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40:76–81. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.33915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.El-Shafey EM, El-Nagar GF, Selim MF, El-Sorogy HA, Sabry AA. Is there a role for endothelin-1 in the hemodynamic changes during hemodialysis? Clin Exp Nephrol. 2008;12:370–375. doi: 10.1007/s10157-008-0065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI Clinical Practice Guidelines for cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45 suppl 4:s49–s59. s69–s75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abraham PA, Macres MG. Blood pressure in hemodialysis patients during amelioration of anemia with erythropoietin. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1991;2:927–936. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V24927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buckner FS, Eschbach JW, Haley NR, Davidson RC, Adamson JW. Hypertension following erythropoietin therapy in anemic hemodialysis patients. Am J Hypertens. 1990;3:947–955. doi: 10.1093/ajh/3.12.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song JH, Park GH, Lee SY, Lee SW, Lee SW, Kim M-J. Effect of Sodium Balance and the Combination of Ultrafiltration Profile during Sodium Profiling Hemodialysis on the Maintenance of the Quality of Dialysis and Sodium and Fluid Balances. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:237–246. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song JH, Lee SW, Suh CK, Kim MJ. Time-averaged concentration of dialysate sodium relates with sodium load and interdialytic weight gain during sodium-profiling hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40:291–301. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.34507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dolson GM, Ellis KJ, Bernardo MV, Prakash R, Adrogue HJ. Acute decreases in serum potassium augment blood pressure. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;26:321–326. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90652-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Kuijk WH, Mulder AW, Peels CH, Harff GA, Leunissen KM. Influence of changes in ionized calcium on cardiovascular reactivity during hemodialysis. Clin Nephrol. 1997;47:190–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henrich WL, Hunt JM, Nixon JV. Increased ionized calcium and left ventricular contractility during hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:19–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198401053100105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sherman RA, Bialy GB, Gazinski B, Bernholc AS, Eisinge RP. The effect of dialysate calcium levels on blood pressure during hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1986;8:244–247. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(86)80033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leunissen KM, van den Berg BW, van Hooff JP. Ionized calcium plays a pivotal role in controlling blood pressure during haemodialysis. Blood Purif. 1989;7:233–239. doi: 10.1159/000169600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gabutti L, Bianchi G, Soldini D, Marone C, Burnier M. Haemodynamic consequences of changing bicarbonate and calcium concentrations in haemodialysis fluids. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008 doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maynard JC, Cruz C, Kleerekoper M, Levin NW. Blood pressure response to changes in serum ionized calcium during hemodialysis. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:358–361. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-104-3-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Sande FM, Cheriex EC, van Kuijk WH, Leunissen KM. Effect of dialysate calcium concentrations on intradialytic blood pressure course in cardiac-compromised patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:125–131. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9669433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kyriazis J, Katsipi I, Stylianou K, Jenakis N, Karida A, Daphnis E. Arterial stiffness alterations during hemodialysis: the role of dialysate calcium. Nephron Clin Pract. 2007;106:c34–c42. doi: 10.1159/000101482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kyriazis J, Stamatiadis D, Mamouna A. Intradialytic and interdialytic effects of treatment with 1.25 and 1. 75 Mmol/L of calcium dialysate on arterial compliance in patients on hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:1096–1103. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(00)70046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blacher J, Demuth K, Guerin AP, Safar ME, Moatti N, London GM. Influence of biochemical alterations on arterial stiffness in patients with end-stage renal disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:535–541. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.4.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blacher J, Guerin AP, Pannier B, Marchais SJ, Safar ME, London GM. Impact of aortic stiffness on survival in end-stage renal disease. Circulation. 1999;99:2434–2439. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.18.2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mourad A, Khoshdel A, Carney S, et al. Haemodialysis-unresponsive blood pressure: cardiovascular mortality predictor? Nephrology (Carlton) 2005;10:438–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2005.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doumas MN, Douma SN, Petidis KM, Vogiatzis KV, Bassagiannis IC, Zamboulis CX. Different effects of losartan and moxonidine on endothelial function during sympathetic activation in essential hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2004;6:682–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2004.03707.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saijonmaa O, Metsarinne K, Fyhrquist F. Carvedilol and its metabolites suppress endothelin-1 production in human endothelial cell culture. Blood Press. 1997;6:24–28. doi: 10.3109/08037059709086442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prasad VS, Palaniswamy C, Frishman WH. Endothelin as a clinical target in the treatment of systemic hypertension. Cardiol Rev. 2009;17:181–191. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181aa8f4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flanigan MJ, Khairullah QT, Lim VS. Dialysate sodium delivery can alter chronic blood pressure management. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;29:383–391. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90199-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suri RS, Nesrallah GE, Mainra R, et al. Daily hemodialysis: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:33–42. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00340705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walsh M, Culleton B, Tonelli M, Manns B. A systematic review of the effect of nocturnal hemodialysis on blood pressure, left ventricular hypertrophy, anemia, mineral metabolism, and health-related quality of life. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1500–1508. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chan CT, Li SH, Verma S. Nocturnal hemodialysis is associated with restoration of impaired endothelial progenitor cell biology in end-stage renal disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F679–F684. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00127.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]