Abstract

Purpose

To determine the frequency of occurrence of limited clinical features which distinguish patients with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) disease from those with non-VKH uveitis.

Design

Comparative case series.

Participants

1147 total patients.

Methods

All patients with bilateral ocular inflammatory disease presenting to any of ten uveitis centers in the three month period between 2006-January-01 and 2006-March-31 (inclusive) were asked to participate. The clinical and historical features of disease were obtained from the participants via direct interview and chart review. Patients were stratified based on whether they were diagnosed with VKH disease or non-VKH uveitis for statistical analysis.

Main Outcome Measures

Presence or absence of various clinical features in the two populations.

Results

Of 1147 patients, 180 were diagnosed with VKH disease and 967 with non-VKH uveitis. Hispanics and Asians were more likely to be diagnosed with VKH than non-VKH disease compared to other ethnicities. In acute disease, the finding of exudative retinal detachment was most likely to be found in VKH disease with a positive predictive value (PPV) of 100 and negative predictive value (NPV) of 88.4, while in chronic disease, sunset glow fundus was most likely to be found, with a PPV of 94.5 and NPV of 89.2.

Conclusions

Numerous clinical findings have been described in the past as important in the diagnosis of VKH. The current study reveals that of these, two are highly specific to this entity in an ethnically and geographically diverse group of patients with non-traumatic bilateral uveitis. These clinical findings are 1. exudative retinal detachment during acute disease and 2. sunset glow fundus during the chronic phase of the disease.

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease (VKH) is a visually disabling bilateral intraocular inflammation usually associated with extraocular manifestations such as meningismus, vitiligo, poliosis, and dysacusis.1–3 The extraocular manifestations typically appear in different phases of the disease and may vary in different ethnic groups.1, 4–6 For example, cutaneous manifestations are typically absent during the acute phase and appear later in the disease course, while the neurologic and auditory manifestations generally precede ocular manifestations. The absence of concurrent extraocular manifestations may have significant implications for both clinical practice and the conduct of clinical studies, as follows. In the area of clinical practice, variation in manifestations and their timing may cause a delay in establishing the correct diagnosis and thus a delay in the initiation of appropriate treatment. This may result in the disease entering the chronic/recurrent phase and in the subsequent development of complications such as glaucoma, cataract, and subretinal neovascularization or fibrosis.1, 7–10 In the area of clinical research, in addition to the issue described for clinical practice, VKH is a relatively uncommon disease and future clinical studies will require international collaboration and pooling of patients of various ethnicities to achieve numbers of subjects sufficient for meaningful conclusions to be drawn. Variations in the presentation of VKH patients can make it difficult to ensure that all subjects enrolled in a clinical study truly have VKH disease. To this end, various diagnostic criteria have been created,4, 11, 12 but developing criteria that are broad enough to encompass the various ways in which VKH may present, while ensuring that non-VKH patients are excluded, is difficult. In addition, none of the published sets of criteria, to our knowledge, has been created based on a sound statistical analysis of the most common and distinguishing manifestations of the disease. As a basis for the development of a statistically and epidemiologically validated set of diagnostic findings, the current multinational study was undertaken to define the clinical features which distinguish VKH from other forms of uveitis.

Methods

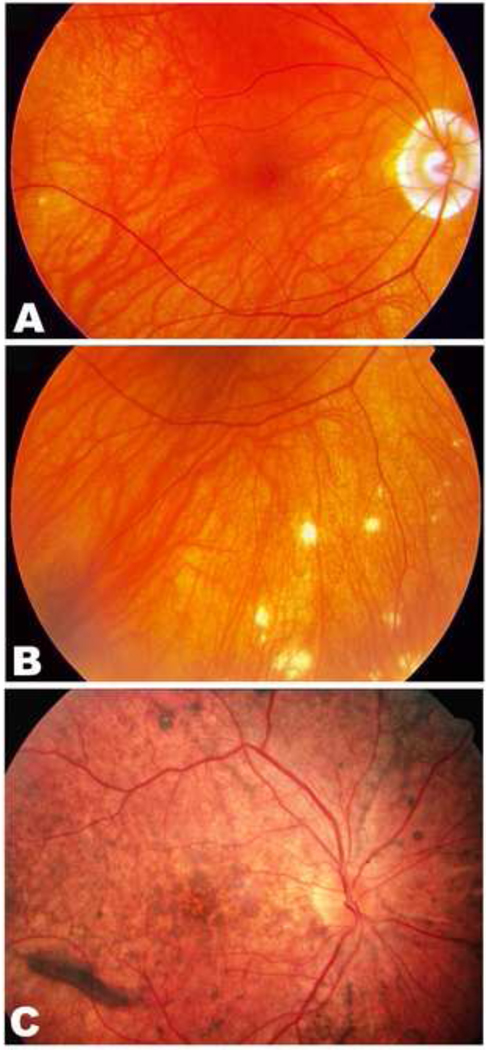

Institutional Review Board (IRB)/Ethics Committee (or equivalent body) approval was obtained at each study site by each site's principal investigator and all research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. For United States sites, all work was compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). The study centers were Doheny Eye Institute; Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh; Singapore National Eye Center; Department of Ophthalmology, Kyorin University School of Medicine; Fattouma Bourguiba University Hospital, University of Paris 1V; University of Rome; Tokyo Medical and Dental University; Ramathibodi Hospital; and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. At each center, all patients with clinical features of bilateral intraocular inflammation, presenting as a new patient or in follow up during the 3-month period from 2006-January-01 to 2006-March-31 (inclusive) were prospectively identified. A standard data capture matrix was developed and distributed to all study sites. The matrix was based on the generally accepted clinical features of VKH and included the set of criteria proposed by the First International Workshop on VKH.11 Sunset glow changes is defined as depigmented fundus showing orange-red discoloration mimicking sunset.10 Standard images consisting of fundus photographs showing sunset glow changes, nummular chorioretinal scars, and retinal pigment epithelial alterations (Figure 1) were distributed to the participating uveitis centers for reference in documenting findings at the time of ophthalmic examination. These standards had been unanimously accepted by the participating international uveitis experts prior to initiation of the study. Data capture was completed at the time of examination by patient query and clinical examination. For patients presenting as a follow up during the study period, data that had been captured on previous visits was also extracted by chart review. Information collected included demographic data, symptoms and clinical findings, diagnostic investigations performed, and final diagnosis. The Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature guidelines for reporting clinical data as regards duration of uveitis, anatomic classification, and course of the disease were utilized.13 Patients with a history of intraocular inflammation of duration of 3 months or less were classified as acute; those with a history of intraocular inflammation with duration of more than 3 months were classified as chronic. No patient was examined for the study more than once.

Figure 1.

Chronic Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Sunset glow fundus (A) and nummular chorioretinal scars (B) in a 54-year-old Asian male with chronic Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease (VKH). Note, there is also peripapillary atrophy. Retinal pigment epithelial changes (C) are present in the fundus of a 36-year-old Hispanic woman with chronic VKH.

The collected data was coded for analysis. Statistical analyses were carried out comparing patients diagnosed with and without VKH. Demographic variables of age, gender and race were compared stratified by uveitis status. Means and standard deviations (sd) for age were compared between groups using independent sample t-tests, while the distributions for gender and race were compared between groups using Fisher’s exact and Chi-square tests. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values and likelihood ratio (95% confidence interval) were calculated for symptoms and clinical findings for VKH and bilateral non-VKH subjects and stratified by acute and chronic uveitis status, as follows: sensitivity [True Positive/(** True Positive + False Negative)] (defined as the probability of correctly identifying subjects who have a disease); specificity [True Negative/(True Negative + False Positive)] (defined as the probability of correctly identifying subjects who do not have a disease); positive predictive value [True Positive/(True Positive + False Positive)] (the probability that if the test diagnoses a subject as having the disease, it is true); and negative predictive value [True Negative/(True Negative + False Negative)] (the probability that if the test is negative the subject does not have the disease). Multiple logistic regression models were constructed using stepwise selection to determine which variables were independently predictive of VKH status. For other models variables were combined using a stepwise analytical approach, first identifying which parameters by univariate assessment were statistically significant, then different combinations of these parameters were tested to see if the specificity or sensitivity improved. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS 9.0 software (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

A total of 1147 patients with bilateral ocular inflammatory disease presented to ten uveitis centers during the study period (Table 1). Of these, 180 patients (15.8%) were diagnosed with VKH. The demographic features of all patients are summarized in Table 2. As this table shows, of patients presenting in the acute phase of disease, Hispanics were more likely to be diagnosed with VKH than non-VKH uveitis. In patients examined during the chronic phase of uveitic disease, Hispanics and Asians were more likely to be diagnosed with VKH than non-VKH, while the reverse was true for Caucasians and African-Americans (Table 2).

Table 1.

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease and Non-Vogt- Koyanagi- Harada disease uveitis patients from ten uveitis centers: the number of patients by center

| Center # | VKH | Non-VKH | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | U.S. (Doheny) | 35 | (21.6%) | 127 | (78.4%) | 162 | |

| 2. | France | 15 | (9.1%) | 150 | (90.9%) | 165 | |

| 3. | India | 22 | (12.8%) | 150 | (87.2%) | 172 | |

| 4. | Italy | 6 | (9.7%) | 56 | (90.3%) | 62 | |

| 5. | Japan (K) | 29 | (19.3%) | 121 | (80.7%) | 150 | |

| 6. | Japan (M) | 8 | (14.5%) | 47 | (85.5%) | 55 | |

| 7. | U.S. (RWR) | 2 | (1.8%) | 109 | (98.2%) | 111 | |

| 8. | Singapore | 32 | (22.2%) | 112 | (77.8%) | 144 | |

| 9. | Thailand | 15 | (34.9%) | 28 | (65.1%) | 43 | |

| 10. | Tunisia | 16 | (19.3%) | 67 | (80.7%) | 83 | |

| Total | 180 | (15.7%) | 967 | (84.3%) | 1147 | ||

U.S.=United States; M=Kyorin University School of Medicine; M=Tokyo Medical and Dental University; RWR= University of Alabama at Birmingham

Table 2.

Demographic features of all patients with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease compared to non-Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease

| VKH | Non VKH | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 180 | 967 | |

| Mean age, years | |||

| Acute uveitis | 40.8 (13.4) | 35.7 (18.3) | 0.23 |

| Chronic uveitis | 44.6 (15.1) | 44.7 (17.6) | 0.98 |

| Gender | |||

| Acute uveitis | |||

| Female | 75% | 59.1% | 0.17 |

| Male | 25% | 40.9% | |

| Chronic uveitis | |||

| Female | 68.1% | 60.6% | |

| Male | 31.9% | 39.4% | |

| Race | |||

| Acute uveitis | |||

| Asian | 35% | 19% | 0.14 |

| African-American | 0% | 3.7% | 1 |

| Caucasian | 35% | 51.8% | 0.23 |

| Hispanic | 25% | 4.4% | 0.006 |

| Asian Indian | 5% | 21.2% | 0.13 |

| Chronic uveitis | |||

| Asian | 47.2% | 34.1% | 0.003 |

| African-American | 2.5% | 9.2% | 0.002 |

| Caucasian | 15.1% | 36.0% | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 19.5% | 4% | <0.001 |

| Asian Indian | 15.7% | 16.7% | 0.82 |

VKH= Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease; the figures in parenthesis represent standard deviation.

Presenting symptoms and clinical findings in all patients are detailed in Table 3. Uveitis classifications for non-VKH patients are provided in Table 4. A comparison of clinical features in acute and chronic VKH with non-VKH patients with anterior, posterior or pan uveitis is provided in Table 5 and Table 6. The acute VKH cases were further compared with posterior or panuveitis non-VKH patients (Table 7). A stepwise logistic regression model for acute and chronic VKH identified exudative retinal detachment and sunset glow fundus as being associated with acute and chronic VKH, (Table 8) with Odds Ratio of >999 (48.02,>999) and 141.66 (54.65, 367.2) respectively. The constellation of bilateral intraocular inflammation and subretinal focal collections of fluid or bullous retinal detachment had a PPV of 100 and a NPV for VKH disease of 88.4 (Table 5). Among patients with chronic uveitis, the findings of sunset glow fundus and vitiligo were more likely to occur in VKH patients as compared to non-VKH patients, with a likelihood ratio varying from 50.2 to 34.6 (Table 6; see Table 9, available at http://aaojournal.org)

Table 3.

Symptoms, Clinical Findings, and Diagnostic study results in All Patients with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease Compared to Non-Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease*

| VKH | Non-VKH | |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | ||

| Headaches | 85/173 (49%) | 180/940 (19%) |

| Photophobia | 84/175 (48%) | 441/939 (47%) |

| Tinnitus | 61/171 (36%) | 63/938 (7%) |

| Neck stiffness | 57/173 (33%) | 122/943 (13%) |

| Difficulty hearing | 45/139 (32%) | 40/835 (5%) |

| Weakness | 36/173 (21%) | 101/928 (11%) |

| Flu like symptoms | 29/170 (17%) | 77/930 (8%) |

| Nausea | 22/174 (13%) | 35/947 (4%) |

| Clinical Findings | ||

| Sunset glow fundus | 103/178 (58%) | 9/951 (1%) |

| Nummular chorioretinal. scars | 82/178 (46%) | 83/952 (9%) |

| RPE clumping/migration | 79/176 (45%) | 103/948 (11%) |

| Vitreous cells | 66/175 (38%) | 351/954 (37%) |

| Cataract | 66/180 (37%) | 323/964 (34%) |

| Anterior chamber cells | 64/180 (36%) | 377/965 (39%) |

| Poliosis | 50/179 (28%) | 113/959 (12%) |

| Anterior chamber flare | 43/179 (24%) | 243/947 (26%) |

| Keratic precipitates | 39/180 (22%) | 188/963 (20%) |

| Vitiligo | 36/178 (20%) | 8/959 (1%) |

| Choroidal thickening | 23/113 (20%) | 7/505 (1%) |

| Hearing loss | 32/179 (18%) | 24/957 (3%) |

| Alopecia | 32/179 (18%) | 46/957 (5%) |

| Disc hyperemia/swelling | 22/176 (13%) | 84/951 (9%) |

| Ocular hypertension | 20/180 (11%) | 84/964 (9%) |

| Glaucoma | 18/179 (10%) | 76/958 (8%) |

| Subretinal fibrosis | 15/178 (8%) | 19/951 (2%) |

| Bullous detachment | 11/178 (6%) | 9/954 (1%) |

| Sugiura sign | 9/175 (5%) | 1/953 (0%) |

| Subretinal fluid | 8/178 (4%) | 15/958 (2%) |

| Subretinal neovascularization | 4/177 (2%) | 11/952 (1%) |

| Diagnostic Testing Results | ||

| FA: D or M or L or P or Choroidal thickening | 111/124 (90%) | 86/282 (30%) |

| FA: D or M or L or P | 106/127 (83%) | 80/487 (16%) |

| CSF pleocytosis | 34/44 (77%) | 10/34 (29%) |

| FA: Optic disc staining | 90/128 (70%) | 176/506 (35%) |

| FA: Multifocal leaks (M) | 89/127 (70%) | 43/503 (9%) |

| FA: Subretinal pooling of dye (P) | 71/127 (56%) | 10/502 (2%) |

| FA: Large placoid areas of hyperfluorescence (L) | 54/126 (43%) | 44/504 (9%) |

| FA: Choroidal perfusion delay (D) | 50/122 (41%) | 15/485 (3%) |

| FA: D or M or L or P and Choroidal thickening | 18/83 (22%) | 1/248 (0%) |

| Choroidal thickening on ultrasound | 23/113 (20%) | 7/505 (1%) |

VKH, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease; RPE= retinal pigment epithelium; FA, fluorescein angiography; D, Choroidal perfusion delay; M, Multifocal leaks on FA; L, Large placoid areas of hyperfluorescence; P, subretinal pooling of dye

In this group there were 8 patients who could not be further classified as acute or chronic ocular inflammations and one of these patients had sunset glow fundus.

Table 4.

Classification of ocular inflammation entities in 967 patients with non-Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease

| Uveitis Entity | Anterior uveitis |

Intermediate uveitis |

Posterior uveitis |

Panuveitis | Without anatomic classification |

TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 274* | 107* | 120* | 110 | 309 | 920* |

| HLA B27 Associated | 72 | 72 | ||||

| Fuchs uveitis syndrome | 6 | 6 | ||||

| Juvenile arthritis associated | 20 | 20 | ||||

| Herpetic associated anterior | 5 | 5 | ||||

| Viral retinitis | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Tuberculosis | 3 | 10 | 11 | 4 | 21 | 49 |

| Toxoplasmosis | 1 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Cytomegalovirus retinitis | 1 | 4 | 5 | |||

| Lyme | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Syphilis | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||

| Pars Planitis | 84 | 84 | ||||

| Sarcoidosis | 8 | 7 | 3 | 95 | 113 | |

| Sympathetic ophthalmia | 16 | 16 | ||||

| Birdshot chorioretinopathy | 32 | 1 | 33 | |||

| Serpiginous | 13 | 13 | ||||

| Multifocal choroiditis | 19 | 19 | ||||

| Systemic lupus erythematosus associated |

2 | 4 | 1 | 7 | ||

| Multiple sclerosis associated | 3 | 3 | ||||

| Behcets | 1 | 2 | 108 | 111 | ||

| Masquerade Syndrome | 11 | 11 | ||||

| Others | 152 | 2 | 54 | 62 | 70 | 340 |

Total number of cases based on anatomic classification; 42 patients had scleritis/episcleritis and 5 had optic neuritis

Table 5.

Acute Disease: Clinical Findings in Patients with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease Compared to Non-Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease (non-Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada subjects included only for anterior, posterior or panuveitis)

| Clinical | VKH | Non VKH | PPV | NPV | Sensi- | Speci- | Likelihood | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | tivity | ficity | Ratio | (95% CI) | ||||||

| Sunset glow fundus | 0/20 | 0% | 1/76 | 1% | 0.0 | 78.9 | 0.0 | 98.7 | 0.0 | . . |

| Bullous detachment | 10/20 | 50% | 0/76 | 0% | 100.0 | 88.4 | 50.0 | 100.0 | . | . . |

| Choroidal thickening | 5/10 | 50% | 1/32 | 3% | 83.3 | 86.1 | 50.0 | 96.9 | 16.0 | ( 2.2,113.8) |

| Subretinal fluid | 6/20 | 30% | 1/76 | 1% | 85.7 | 84.3 | 30.0 | 98.7 | 22.8 | ( 3.2,163.6) |

| Hearing loss | 4/20 | 20% | 2/77 | 3% | 66.7 | 82.4 | 20.0 | 97.4 | 7.7 | ( 1.8, 33.8) |

| Vitiligo | 1/20 | 5% | 1/77 | 1% | 50.0 | 80.0 | 5.0 | 98.7 | 3.8 | ( 0.4, 42.0) |

| Alopecia | 2/20 | 10% | 0/77 | 0% | 100.0 | 81.1 | 10.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | . . |

| Nummular chor. scars | 0/20 | 0% | 4/76 | 5% | 0.0 | 78.3 | 0.0 | 94.7 | 0.0 | . . |

| RPE clumping/migration | 2/19 | 11% | 5/76 | 7% | 28.6 | 80.7 | 10.5 | 93.4 | 1.6 | ( 0.4, 6.8) |

| Disc hyperemia/swelling | 9/19 | 47% | 12/76 | 16% | 42.9 | 86.5 | 47.4 | 84.2 | 3.0 | ( 1.5, 6.1) |

| Poliosis | 1/20 | 5% | 7/77 | 9% | 12.5 | 78.7 | 5.0 | 90.9 | 0.5 | ( 0.1, 3.9) |

| Vitreous cells | 12/19 | 63% | 27/76 | 36% | 30.8 | 87.5 | 63.2 | 64.5 | 1.8 | ( 1.0, 3.1) |

| Anterior chamber cells | 12/20 | 60% | 52/76 | 68% | 18.8 | 75.0 | 60.0 | 31.6 | 0.9 | ( 0.5, 1.5) |

| Anterior chamber flare | 5/20 | 25% | 30/76 | 39% | 14.3 | 75.4 | 25.0 | 60.5 | 0.6 | ( 0.3, 1.5) |

| Keratic precipitates | 2/20 | 10% | 22/77 | 29% | 8.3 | 75.3 | 10.0 | 71.4 | 0.4 | ( 0.1, 1.4) |

| Sugiura sign | 0/19 | 0% | 0/75 | 0% | . | 79.8 | 0.0 | 100.0 | . | . . |

| (Subretinal Fluid or | 11/20 | 55% | 1/76 | 1% | 91.7 | 89.3 | 55.0 | 98.7 | 41.8 | ( 5.9,295.1) |

| Bullous retinal detachment) | ||||||||||

| (Subretinal Fluid or | 5/10 | 50% | 0/32 | 0% | 100.0 | 86.5 | 50.0 | 100.0 | . | . . |

| Bullous retinal detachment) | ||||||||||

| and choroidal thickening | ||||||||||

| (Subretinal Fluid or | 0/20 | 0% | 0/76 | 0% | . | 79.2 | 0.0 | 100.0 | . | . . |

| Bullous retinal detachment) | ||||||||||

| and alopecia | ||||||||||

| (Subretinal Fluid or | 3/20 | 15% | 0/76 | 0% | 100.0 | 81.7 | 15.0 | 100.0 | . | . . |

| Bullous retinal detachment) | ||||||||||

| and hearing loss | ||||||||||

| (Subretinal Fluid or | 6/20 | 30% | 0/74 | 0% | 100.0 | 84.1 | 30.0 | 100.0 | . | . . |

| Bullous retinal detachment) | ||||||||||

| and (headache or neck stiffness) | ||||||||||

PPV= Positive predictive value; NPV= Negative predictive value; C!= confidence interval

Table 6.

Chronic Disease: Clinical Findings in Patients with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease Compared to Non-Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease (Non-Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada subjects included only for anterior, posterior or panuveitis)

| Clinical | VKH | No VKH | PPV | NPV | Sensi- | Speci- | Likelihood | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | tivity | ficity | Ratio | (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Sunset glow fundus | 103/158 | 65% | 6/462 | 1% | 94.5 | 89.2 | 65.2 | 98.7 | 50.2 | (22.6,111.3) | .000 | |

| Sugiura sign | 9/156 | 6% | 1/467 | 0% | 90.0 | 76.0 | 5.8 | 99.8 | 26.9 | ( 3.8,193.0) | .002 | |

| Vitiligo | 35/158 | 22% | 3/469 | 1% | 92.1 | 79.1 | 22.2 | 99.4 | 34.6 | (11.2,107.4) | .000 | |

| Choroidal thickening | 18/103 | 17% | 3/225 | 1% | 85.7 | 72.3 | 17.5 | 98.7 | 13.1 | ( 4.2, 40.9) | .000 | |

| Nummular chor. scars | 82/158 | 52% | 45/463 | 10% | 64.6 | 84.6 | 51.9 | 90.3 | 5.3 | ( 3.9, 7.3) | .000 | |

| RPE clumping/migration | 77/157 | 49% | 67/461 | 15% | 53.5 | 83.1 | 49.0 | 85.5 | 3.4 | ( 2.6, 4.4) | .000 | |

| Hearing loss | 28/159 | 18% | 13/469 | 3% | 68.3 | 77.7 | 17.6 | 97.2 | 6.4 | ( 3.6, 11.3) | .000 | |

| Alopecia | 30/159 | 19% | 33/469 | 7% | 47.6 | 77.2 | 18.9 | 93.0 | 2.7 | ( 1.8, 4.1) | .000 | |

| Poliosis | 49/159 | 31% | 63/470 | 13% | 43.8 | 78.7 | 30.8 | 86.6 | 2.3 | ( 1.7, 3.1) | .000 | |

| Vitreous cells | 54/156 | 35% | 114/466 | 24% | 32.1 | 77.5 | 34.6 | 75.5 | 1.4 | ( 1.1, 1.9) | .014 | |

| Disc hyperemia/swelling | 13/157 | 8% | 28/464 | 6% | 31.7 | 75.2 | 8.3 | 94.0 | 1.4 | ( 0.8, 2.4) | .329 | |

| Keratic precipitates | 37/160 | 23% | 84/470 | 18% | 30.6 | 75.8 | 23.1 | 82.1 | 1.3 | ( 0.9, 1.8) | .146 | |

| Anterior chamber flare | 38/159 | 24% | 111/464 | 24% | 25.5 | 74.5 | 23.9 | 76.1 | 1.0 | ( 0.7, 1.4) | .995 | |

| Anterior chamber cells | 52/160 | 33% | 167/472 | 35% | 23.7 | 73.8 | 32.5 | 64.6 | 0.9 | ( 0.7, 1.2) | .508 | |

| Bullous detachment | 1/158 | 1% | 3/463 | 1% | 25.0 | 74.6 | 0.6 | 99.4 | 1.0 | ( 0.1, 7.5) | .984 | |

| Subretinal fluid | 2/158 | 1% | 7/466 | 2% | 22.2 | 74.6 | 1.3 | 98.5 | 0.8 | ( 0.2, 3.5) | .830 | |

| Sunset glow fundus or Nummular chor. scars |

117/159 | 74% | 48/463 | 10% | 70.9 | 90.8 | 73.6 | 89.6 | 7.1 | ( 5.3, 9.4) | .000 | |

| Sunset glow fundus or | 118/158 | 75% | 49/459 | 11% | 70.7 | 91.1 | 74.7 | 89.3 | 7.0 | ( 5.3, 9.3) | .000 | |

| Nummular chor. scars or Sugiura sign | ||||||||||||

| (Sunset glow fundus or | 63/158 | 40% | 8/461 | 2% | 88.7 | 82.7 | 39.9 | 98.3 | 23.0 | (11.5, 45.9) | .000 | |

| Nummular chor. scars) and (vitiligo or alopecia or | ||||||||||||

| poliosis or hearing loss) | ||||||||||||

| (Sunset glow fundus or | 64/157 | 41% | 8/458 | 2% | 88.9 | 82.9 | 40.8 | 98.3 | 3 | 23.3 | (11.7, 46.6) | .000 |

| Nummular chor. scars or Sugiura sign) and | ||||||||||||

| (vitiligo or alopecia or poliosis or hearing loss) | ||||||||||||

| Sunset glow fundus and | 58/157 | 37% | 0/802 | 0% | 100.0 | 89.0 | 36.9 | 100.0 | . | . . | ||

| (vitiligo or alopecia or poliosis or hearing loss) | ||||||||||||

chor=chorioretinal; RD= retinal detachment; CI=Confidence interval; PPV=Positive predictive value; NPV=Negative predictive value; RPE=Retinal pigment epithelium; VKH=Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease

Table 7.

Acute Disease: Clinical Findings in Patients with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease Compared to Non-Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease (non-Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada subjects included only for posterior or panuveitis)

| Clinical | VKH | Non VKH | PPV | NPV | Sensi- | Speci- | Likelihood | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | tivity | ficity | Ratio | (95% CI) | ||||||

| Sunset glow fundus | 0/20 | 0% | 1/30 | 3% | 0.0 | 59.2 | 0.0 | 96.7 | 0.0 | . . |

| Bullous detachment | 10/20 | 50% | 0/30 | 0% | 100.0 | 75.0 | 50.0 | 100.0 | . | . . |

| Choroidal thickening | 5/10 | 50% | 0/14 | 0% | 100.0 | 73.7 | 50.0 | 100.0 | . | . . |

| Subretinal fluid | 6/20 | 30% | 1/30 | 3% | 85.7 | 67.4 | 30.0 | 96.7 | 9.0 | ( 1.3, 63.3) |

| Hearing loss | 4/20 | 20% | 1/30 | 3% | 80.0 | 64.4 | 20.0 | 96.7 | 6.0 | ( 0.8, 43.3) |

| Vitiligo | 1/20 | 5% | 0/30 | 0% | 100.0 | 61.2 | 5.0 | 100.0 | . | . . |

| Alopecia | 2/20 | 10% | 0/30 | 0% | 100.0 | 62.5 | 10.0 | 100.0 | . | . . |

| Nummular chor. scars | 0/20 | 0% | 4/30 | 13% | 0.0 | 56.5 | 0.0 | 86.7 | 0.0 | . . |

| RPE clumping/migration | 2/19 | 11% | 5/30 | 17% | 28.6 | 59.5 | 10.5 | 83.3 | 0.6 | ( 0.2, 2.6) |

| Disc hyperemia/swelling | 9/19 | 47% | 6/30 | 20% | 60.0 | 70.6 | 47.4 | 80.0 | 2.4 | ( 1.0, 5.4) |

| Poliosis | 1/20 | 5% | 4/30 | 13% | 20.0 | 57.8 | 5.0 | 86.7 | 0.4 | ( 0.1, 2.7) |

| Vitreous cells | 12/19 | 63% | 17/29 | 59% | 41.4 | 63.2 | 63.2 | 41.4 | 1.1 | ( 0.6, 1.8) |

| Anterior chamber cells | 12/20 | 60% | 18/29 | 62% | 40.0 | 57.9 | 60.0 | 37.9 | 1.0 | ( 0.6, 1.6) |

| Anterior chamber flare | 5/20 | 25% | 6/30 | 20% | 45.5 | 61.5 | 25.0 | 80.0 | 1.3 | ( 0.5, 3.3) |

| Keratic precipitates | 2/20 | 10% | 9/30 | 30% | 18.2 | 53.8 | 10.0 | 70.0 | 0.3 | ( 0.1, 1.3) |

| Sugiura sign | 0/19 | 0% | 0/28 | 0% | . | 59.6 | 0.0 | 100.0 | . | . . |

| (Subretinal Fluid or | 11/20 | 55% | 1/30 | 3% | 91.7 | 76.3 | 55.0 | 96.7 | 16.5 | ( 2.4,114.2) |

| Bullous retinal detachment | ||||||||||

| (Subretinal Fluid or | 5/10 | 50% | 0/14 | 0% | 100.0 | 73.7 | 50.0 | 100.0 | . | . . |

| Bullous retinal detachment) | ||||||||||

| and choroidal thickening | ||||||||||

| (Subretinal Fluid or | 0/20 | 0% | 0/30 | 0% | . | 60.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | . | . . |

| Bullous retinal detachment) | ||||||||||

| and alopecia | ||||||||||

| (Subretinal Fluid or | 3/20 | 15% | 0/30 | 0% | 100.0 | 63.8 | 15.0 | 100.0 | . | . . |

| Bullous retinal detachment) | ||||||||||

| and hearing loss | ||||||||||

| (Subretinal Fluid or | 6/20 | 30% | 0/28 | 0% | 100.0 | 66.7 | 30.0 | 100.0 | . | . . |

| Bullous retinal detachment) | ||||||||||

| and (headache or neck stiffness) | ||||||||||

Table 8.

Acute and Chronic Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease clinical features: Stepwise logistic regression models

| Dependent variable = VKH | Odds Ratio Estimate (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Acute disease | ||

| Exudative RD | >999 (48.02,>999) | <0.0001 |

| Alopecia | 81.23 (2.47, >999) | 0.01 |

| Disc hyperemia | 5.28 (1.02, 27.42) | 0.05 |

| Asian | 24.48 (2.38,251.9) | 0.007 |

| Hispanic | 59.76 (3.77, 948.2) | 0.004 |

| Model 2: Chronic disease | ||

| Sunset glow fundus | 141.66 (54.65, 367.2) | <0.0001 |

| Vitiligo | 11.73 (3.59, 38.33) | <0.0001 |

| Alopecia | 3.20 (1.40, 7.31) | 0.0005 |

| Nummular chorioretinal scars | 2.83 (1.34,5.98) | 0.01 |

| Vitreous cells | 0.39 (0.18,0.83) | 0.02 |

| Asian | 3.48 (1.60, 7.60) | 0.002 |

| Hispanic | 13.25 (4.63, 37.88) | 0.0003 |

VKH= Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease; CI=Confidence interval; RD=Retinal detachment

Table 9.

Chronic Disease: Clinical Findings in Patients with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease Compared to Non-Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease (Non-Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada subjects included only for posterior or panuveitis)

| Clinical | VKH | No VKH | PPV | NPV | Sensi- | Speci- | Likelihood | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | NPV | tivity | ficity | Ratio | (95% CI) | |||||

| Sunset glow fundus | 103/158 | 65% | 5/195 | 3% | 95.4 | 77.6 | 65.2 | 97.4 | 25.4 | (10.7, 60.5) |

| Sugiura sign | 9/156 | 6% | 0/196 | 0% | 100.0 | 57.1 | 5.8 | 100.0 | . | . . |

| Vitiligo | 35/158 | 22% | 1/198 | 1% | 97.2 | 61.6 | 22.2 | 99.5 | 43.9 | ( 6.2,310.1) |

| Choroidal thickening | 18/103 | 17% | 2/96 | 2% | 90.0 | 52.5 | 17.5 | 97.9 | 8.4 | ( 2.1, 33.3) |

| Nummular chor. scars | 82/158 | 52% | 40/196 | 20% | 67.2 | 67.2 | 51.9 | 79.6 | 2.5 | ( 1.9, 3.4) |

| RPE clumping/migration | 77/157 | 49% | 59/194 | 30% | 56.6 | 62.8 | 49.0 | 69.6 | 1.6 | ( 1.2, 2.1) |

| Hearing loss | 28/159 | 18% | 6/198 | 3% | 82.4 | 59.4 | 17.6 | 97.0 | 5.8 | ( 2.6, 13.0) |

| Alopecia | 30/159 | 19% | 16/198 | 8% | 65.2 | 58.5 | 18.9 | 91.9 | 2.3 | ( 1.4, 3.9) |

| Poliosis | 49/159 | 31% | 28/198 | 14% | 63.6 | 60.7 | 30.8 | 85.9 | 2.2 | ( 1.5, 3.2) |

| Vitreous cells | 54/156 | 35% | 68/195 | 35% | 44.3 | 55.5 | 34.6 | 65.1 | 1.0 | ( 0.8, 1.3) |

| Disc hyperemia/swelling | 13/157 | 8% | 15/195 | 8% | 46.4 | 55.6 | 8.3 | 92.3 | 1.1 | ( 0.6, 2.0) |

| Keratic precipitates | 37/160 | 23% | 29/198 | 15% | 56.1 | 57.9 | 23.1 | 85.4 | 1.6 | ( 1.1, 2.4) |

| Anterior chamber flare | 38/159 | 24% | 40/195 | 21% | 48.7 | 56.2 | 23.9 | 79.5 | 1.2 | ( 0.8, 1.7) |

| Anterior chamber cells | 52/160 | 33% | 52/199 | 26% | 50.0 | 57.6 | 32.5 | 73.9 | 1.2 | ( 0.9, 1.7) |

| Bullous RD | 1/158 | 1% | 1/195 | 1% | 50.0 | 55.3 | 0.6 | 99.5 | 1.2 | ( 0.1, 13.6) |

| Subretinal fluid | 2/158 | 1% | 4/196 | 2% | 33.3 | 55.2 | 1.3 | 98.0 | 0.6 | ( 0.1, 2.8) |

| Sunset glow fundus or Nummular chor. scars |

117/159 | 74% | 42/196 | 21% | 73.6 | 78.6 | 73.6 | 78.6 | 3.4 | ( 2.6, 4.6) |

| Sunset glow fundus or | 118/158 | 75% | 42/194 | 22% | 73.8 | 79.2 | 74.7 | 78.4 | 3.4 | ( 2.6, 4.6) |

| Nummular chor. scars or Sugiura sign | ||||||||||

| (Sunset glow fundus or | 63/158 | 40% | 8/195 | 4% | 88.7 | 66.3 | 39.9 | 95.9 | 9.7 | ( 4.9, 19.3) |

| Nummular chor. scars) and (vitiligo or alopecia or | ||||||||||

| poliosis or hearing loss) | ||||||||||

| (Sunset glow fundus or | 64/157 | 41% | 8/194 | 4% | 88.9 | 66.7 | 40.8 | 95.9 | 9.9 | ( 5.0, 19.6) |

| Nummular chor. scars or Sugiura sign) and | ||||||||||

| (vitiligo or alopecia or poliosis or hearing loss) | ||||||||||

| Sunset glow fundus and | 58/157 | 37% | 0/802 | 0% | 100.0 | 89.0 | 36.9 | 100.0 | . | . . |

| (vitiligo or alopecia or poliosis or hearing loss) | ||||||||||

chor= chorioretinal; RD= retinal detachment; CI=Confidence interval; PPV=Positive predictive value; NPV=Negative predictive value; RPE=Retinal pigment epithelium

Discussion

Uveitis is not a single disease but rather a multitude of entities with different pathophysiologies, prognoses, and treatment requirements. Thus establishing, as definitively as possible, a specific diagnosis in uveitic disease is important to allow appropriate counseling, treatment, and surveillance of patients. In the absence of definitive diagnostic testing, agreement on a set of features that are characteristic and typical for a given uveitic entity is necessary in order to allow the clinician to provide the above clinical services and in addition, to allow the clinical researcher to define homogeneous populations of patients for clinical study. As evidenced by the publication of multiple papers proposing or evaluating diagnostic criteria for VKH disease,2, 3, 11, 12, 14 a definitive set of such criteria for this condition has not been universally agreed upon. In part, this stems from the multiphasic nature of VKH, with varying clinical features in different stages of the disease as well as the potential for ethnic variation in disease manifestations. One of the first steps in establishing diagnostic criteria is to determine, in as widely applicable a population as possible, the occurrence of clinical signs and symptoms felt by those clinicians with broad exposure in the condition to be prototypical. In the current study, the authors sought to determine the frequency of features considered typical for VKH in patients with acute or chronic uveitis, presenting to uveitis clinics in ten geographically and ethnically diverse centers. Initial analyses of the presence or absence of these findings in VKH and non-VKH anterior, posterior or panuveitis patients have revealed several distinguishing features.

While considered a systemic condition, VKH can present with disease findings limited to intraocular inflammation. In patients with acute VKH, 54% had only ocular manifestations, while in chronic disease, 40.9% had findings limited to the eyes.15 As previously published diagnostic criteria include, as a variable requirement, the presence of extraocular manifestations, this raises the question of what ocular features were considered by the uveitis experts to be specific to VKH.

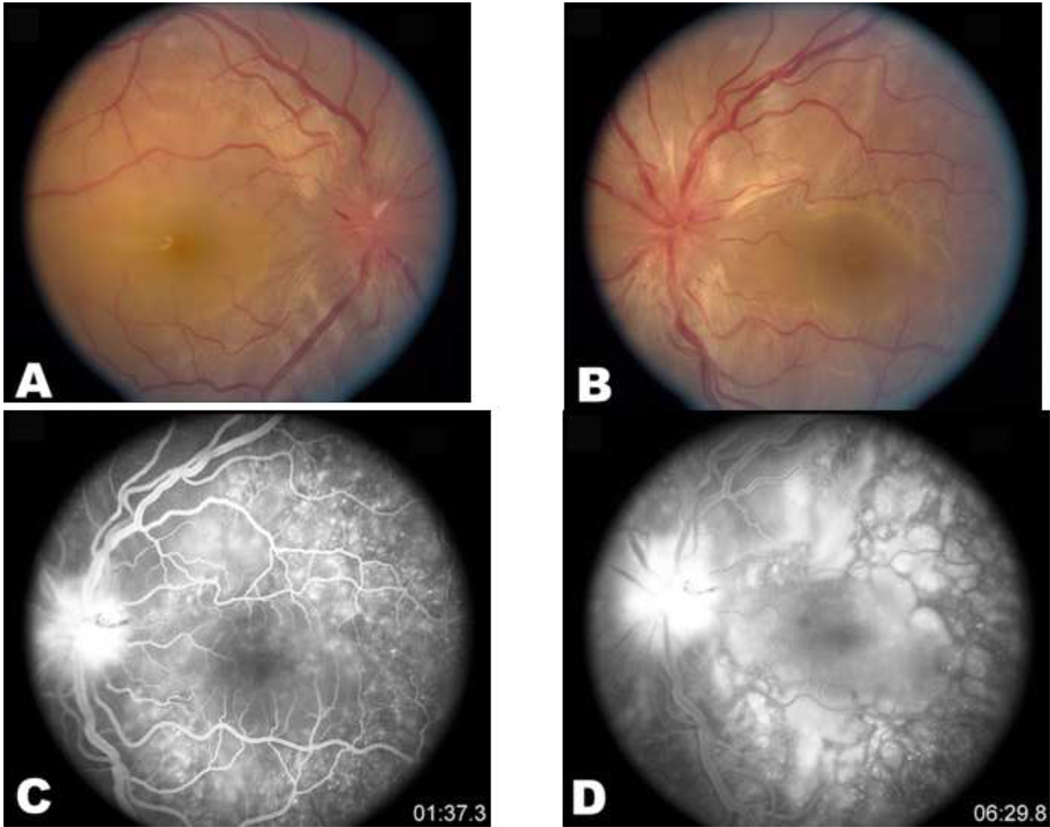

It is generally agreed that diffuse choroidal thickening is a hallmark of acute VKH disease.1, 11 While the number of acute cases with choroidal thickening documented by ultrasonography was limited in the current study, all such patients also had retinal findings (Table 4, Table 5 and Table 7). This indicates that in acute uveitis, the presence of bilateral intraocular inflammation with the retinal findings considered typical for VKH (as detailed in Table 4) may be sufficient evidence that choroidal involvement and thickening exist. However, in patients with uveitis without clinically apparent exudative retinal detachments, ultrasonography and fluorescein angiography can detect choroidal and retinal findings.16–20 In the current report, robust positive and negative predictive values and likelihood ratios of the various documented clinical findings indicate that in acute uveitis, the presence of bilateral exudative retinal detachments (Figure 2) in a patient with bilateral intraocular inflammation strongly suggests acute VKH.

Figure 2.

Acute Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Fundus shows bilateral exudative retinal detachments involving the macula (A and B). The fluorescein angiogram reveals pinpoint leaks at the level of retinal pigment epithelium during the arterio-venous phase (C) and collection of the dye in the subretinal space during the late phase (D).

In those patients with chronic disease diagnosed as VKH, the findings of sunset glow fundus and Sugiura sign were distinguishing. Sugiura sign appears to be observed mostly in patients from Japan,1, 2, 21 suggesting that either non-Japanese VKH patients do not develop perilimbal depigmentation or that the sign is under-recognized outside Japan.

Extraocular signs such as vitiligo, alopecia, poliosis and hearing loss develop during the course of VKH disease and are seen mainly in patients with chronic disease.1 However, the combination of these extraocular findings with sunset glow fundus changes did not improve the likelihood ratio or the positive and negative predictive values (Table 6), indicating that the sunset glow fundus is a uniquely distinctive feature of chronic VKH disease, and clearly suggests that sunset glow fundus alone is sufficient to diagnose chronic VKH.

Ancillary testing is frequently utilized in support of the diagnosis of VKH. In the current study, 127 VKH patients underwent fluorescein angiography and had results available; 487 non-VKH patients underwent fluorescein angiography. Of the 127 VKH patients, 106 (83%) showed one or more angiographic findings (Table 3). In contrast, of the 487 patients with non-VKH disease, 80 (16%) showed one or more angiographic findings. Pleocytosis of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a common finding in patients with acute VKH and in fact is listed in the diagnostic criteria currently published.2, 3, 15,16 In the current study, of 44 patients who underwent CSF analysis and whose results were available, 34 (77%) were found to have pleocytosis. In 34 non-VKH patients undergoing CSF analysis with available results, 10 (29%) were found to have pleocytosis (Table 3). Thus while such data shows that CSF analysis may be a useful procedure for supporting the diagnosis of VKH, it is probably no superior to fluorescein angiography.

It is interesting to note that VKH disease can present in patients with clinical features limited to the eye in the acute phase in the form of bilateral uveitis associated with exudative retinal detachment, while in the chronic phase VKH patients may present with sunset glow fundus without extraocular finding. Recognition of this isolated ocular variant of acute and chronic VKH is important for prompt diagnosis. More over the current study clearly shows in patients with bilateral uveitis, the importance of exudative retinal detachment and sunset glow fundus changes as the main diagnostic findings in acute and chronic VKH respectively. Sunset glow fundus is a descriptive and somewhat subjective clinical term; but the definition has not been a matter of disagreement among uveitis specialists in the setting of the diagnosis of chronic VKH. However, the definition of the term has not been standardized/validated, and the condition might be confounded with the albinotic fundi of some Caucasian individuals. In chronic VKH, the sunset glow changes result from depigmentation of the choroid, which leads to a discoloration of the fundus; the change may be from brunette to blonde, or it may present as an exaggerated reddish glow, resembling an albinotic fundus, but there is usually migration and clumping of pigment and discrete atrophic spots. 22,23.24 In the current study the possible similarities between the sunset glow fundus and the fundus of normal Caucasian individuals may have played a role in the under recognition and/or difficulty in differentiating normal fundus from the depigmented fundus in Caucasians. Of note, only 15% of those individuals diagnosed with chronic VKH (when the presence of sunset glow fundus is a prominent feature, observed in 65%) are Caucasian; in comparison, Caucasians represented 35% of those individuals diagnosed with acute VKH (Table 2 and Table 6). However, a further standardized approach in VKH individuals, in particular in Caucasians, may address the need for a more precise recognition of this important clinical finding, allowing its differentiation from a normally hypopigmented fundus.

In conclusion, to our knowledge this is the first prospective international study on the features of VKH in an ethnically and geographically diverse study group. This data provides information regarding clinical features of VKH as compared to non-VKH disease and reveals several of these features as distinctive for VKH. It is true that an argument of circular reasoning could be made against the methodology utilized, in that cases of uveitis were diagnosed based on the opinion of various uveitis experts, which certainly have established ideas of what constitutes VKH disease. It thus is not surprising that the features these experts considered key to a diagnosis of VKH are more common in those patients diagnosed with VKH. However, in diseases such as VKH, which lack definitive, objective diagnostic testing, establishing criteria for diagnosis typically begins with a consensus agreement on what clinical features typify that disease. We thus believe that the current study provides a foundation toward development of widely accepted diagnostic criteria, by establishing those features that uveitis specialists consider diagnostic for VKH. The next step in establishing diagnostic criteria is to compile a selection of cases possessing and lacking these features, followed by review by uveitis specialists with determination of the features considered essential in establishing the diagnosis of VKH disease. However, the current study shows that limited clinical features are adequate in arriving at the diagnosis of VKH that can be agreeable to international experts on this disease entity.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by NIH core grant EY 3040

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Moorthy RS, Inomata H, Rao NA. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 1995;39:265–292. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(05)80105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitamura M, Takami K, Kitaichi N, et al. Comparative study of two sets of criteria for the diagnosis of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada's disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:1080–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamaki K, Hara K, Sakuragi S. Application of revised diagnostic criteria for Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease in Japanese patients. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2005;49:143–148. doi: 10.1007/s10384-004-0165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugiura S. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1978;22:9–35. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beniz J, Forster DJ, Lean JS, et al. Variations in clinical features of the Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Retina. 1991;11:275–280. doi: 10.1097/00006982-199111030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohno S, Char DH, Kimura SJ, O'Connor GR. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1977;83:735–740. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(77)90142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubsamen PE, Gass JD. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome: clinical course, therapy, and long-term visual outcome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:682–687. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080050096037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moorthy RS, Chong LP, Smith RE, Rao NA. Subretinal neovascular membranes in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;116:164–170. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71280-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bykhovskaya I, Thorne JE, Kempen JH, et al. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: clinical outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:674–678. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keino H, Goto H, Usui M. Sunset glow fundus in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease with and without chronic ocular inflammation. Graefe's Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2002;240:878–882. doi: 10.1007/s00417-002-0538-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Read RW, Holland GN, Rao NA, et al. International Committee on Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease Nomenclature. Revised diagnostic criteria for Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: report of an international committee on nomenclature. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:647–652. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)00925-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snyder DA, Tessler HH. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;90:69–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data: results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugiura S. Some observations on uveitis in Japan, with special reference to Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada and Behcet diseases [in Japanese] Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1976;80:1285–1326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao NA, Sukavatcharin S, Tsai JH. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease diagnostic criteria. Int Ophthalmol. 2007;27:195–199. doi: 10.1007/s10792-006-9021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai JH, Sukavatcharin S, Rao NA. Utility of lumbar puncture in diagnosis of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Int Ophthalmol. 2007;27:189–194. doi: 10.1007/s10792-007-9044-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forster DJ, Cano MR, Green RL, Rao NA. Echographic features of the Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:1421–1426. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070120069031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mantovani A, Resta A, Herbort CP, et al. Work-up, diagnosis and management of acute Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: a case of acute myopization with granulomatous uveitis. Int Ophthalmol. 2007;27:105–115. doi: 10.1007/s10792-007-9052-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang P, Ren Y, Li B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome in Chinese patients. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:606–614. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuo IC, Rechdouni A, Rao NA, et al. Subretinal fibrosis in patients with Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1721–1728. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao NA, Moorthy RS, Inomata H. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Intl Ophthalmol Clin. 1995 Spring;35(2):69–86. doi: 10.1097/00004397-199503520-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herbort CP, Mochizuki M. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: inquiry into the genesis of a disease name in the historical context of Switzerland and Japan. Int Ophthalmol. 2007;27:67–79. doi: 10.1007/s10792-007-9083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inomata H, Rao NA. Depigmented Atrophic Lesions in Sunset Glow Fundi of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:607–614. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00851-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Usui Y, Goto H, Sakai J, Takeuchi M, Usui M, Rao NA. Presumed Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease with unilateral ocular involvement. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247:1127–1132. doi: 10.1007/s00417-009-1068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]