Abstract

Examinations of heavy drinking and dating violence have typically focused on either female victimization or male perpetration; yet recent findings indicate that mutual aggression is the most common pattern of dating violence. The current study investigated the relation between heavy drinking and dating violence for both men and women. Participants (N = 2,247) completed surveys that assessed their heavy drinking and dating violence frequency across the first three years of college. Findings indicated that heavy drinking and dating violence were both relatively stable across time for men and women, but the relation between heavy drinking and dating violence differed by gender. For men, heavy drinking and dating violence were concurrently associated during their freshman year (Year 1), whereas for women heavy drinking during sophomore year (Year 2) predicted dating violence in their junior year (Year 3). In addition to providing educational material on healthy relationships and conflict resolution techniques, intervention efforts should target both heavy drinking and dating violence for men during or prior to their freshman year of college, whereas women may primarily benefit from efforts to reduce their heavy drinking.

Keywords: alcohol, dating violence, physical aggression, heavy drinking

1. Introduction

The prevalence of dating violence has been shown to increase dramatically from the ages of 15 to 25, reaching its peak between 20 to 25 years of age (O’Leary, 1999). As many as one in three college couples in the United States report at least one incident of dating violence (Jackson, 1999; Lewis & Fremouw, 2001; White & Smith, 2009), and physical aggression has been found to occur in 9–21% of dating relationships in the year prior to the assessment (Shook, Gerrity, Jurich, & Segrist, 2000; White & Smith, 2009). Studies examining physical dating violence perpetration and victimization for both men and women have found that women’s rates were either similar or higher than those of men. As many as 42% of women and 37% of men report perpetrating dating violence and 37% of women and 45% of men report having been a victim of dating violence (Arias, Samios, & O’Leary, 1987; Cyr, McDuff, & Wright, 2006; Luthra & Gidycz, 2006; Magdol et al., 1997; Muñoz-Rivas, Graña, O’Leary, & González, 2007; Riggs, O’Leary, & Breslin, 1990; White & Koss, 1991). These high rates are problematic considering the myriad of negative consequences associated with physically aggressive behaviors, including physical injuries (American Medical Association, 1992; Muñoz-Rivas et al., 2007) and mental health problems such as depression and anxiety (Cascardi, O’Leary, Lawrence, & Schlee, 1995; Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2008). Although both men and women experience negative consequences, women sustain more physical injuries (Archer, 2000; Muñoz-Rivas et al., 2007), and experience more depression and anxiety (Magdol et al., 1997; Vivian & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 1994) as a result of aggression than do men.

The overall occurrence of dating violence has been shown to be stable over a 3-month period among dating couples who remained in their relationships (O’Leary & Smith Slep, 2003). College students, however, may change dating partners frequently, especially if one or both partners are aggressive. Thus, it is important to investigate the stability of aggressive behaviors over time without limiting the sample to dating couples who stay together. Studies not limited to individuals who remained in the same relationship over time provide evidence to suggest that dating violence is stable regardless of relationship stability. For example, a meta-analytic review of the literature suggested that individuals with a history of perpetrating physical aggression were at greater risk of perpetrating in the future, and victims who were also physically aggressive with their partner were at increased risk of future victimization (Stith, Smith, Penn, Ward, & Tritt, 2004). A recent prospective study of dating violence among men revealed that a history of perpetrating physical aggression in dating relationships was predictive of future perpetration (Gidycz, Warkentin, & Orchowski, 2007).

1.1. Concurrent Associations between Heavy Drinking and Dating Violence Perpetration and Victimization

Frequent heavy drinking has been related to the occurrence of partner violence more broadly (Fals-Stewart, Golden, & Schumacher, 2003; Leonard & Quigley, 1999; Quigley & Leonard, 2000), with cross-sectional studies indicating that consuming alcohol prior to an aggressive incident increased the likelihood of occurrence and severity of aggression (Fals-Stewart, 2003; Shook et al., 2000; Testa, Quigley, & Leonard, 2003). Although these studies have focused on marital violence, college men characterized as being physically abusive with a dating partner reported more alcohol problems than men who were characterized as psychologically abusive or who were not abusive at all (Lundeberg, Stith, Penn, & Ward, 2004). One possible explanation for this concurrent association between heavy drinking and dating violence is based on the alcohol myopia theory, whereby alcohol consumption influences attention and other cognitive processes that typically inhibit behavioral responses such as aggression (Curtin, Patrick, Lang, Cacioppo, & Birbaumer, 2001; Giancola, 2000; Steele & Josephs, 1990). According to this theory, individuals under the influence of alcohol will be more likely to attend to the most salient cues in their environment (e.g., a conflict with a dating partner), and not on the more distal negative consequences (e.g., relationship dissolution) associated with acting aggressively.

1.2. Longitudinal Associations between Heavy Drinking and Dating Violence Perpetration and Victimization

Heavy drinking has been shown to predict aggression perpetration among married couples over time (e.g., Leonard & Senchak, 1996, Quigley & Leonard, 1999). This longitudinal association may be related to an increase in relationship discord (Leonard, 2001), or a decrease in relationship satisfaction due to heavy drinking (Heyman, O’Leary, & Jouriles, 1995; Homish & Leonard, 2007). In addition, heavy drinking has been shown to lead to other behavioral risks such as generalized aggression and risky sexual practices (e.g., Neal & Fromme, 2007), which may influence subsequent dating violence (Leonard & Quigley, 1999; Leonard & Senchak, 1993, 1996). The longitudinal relation between heavy drinking and dating violence appears to be less consistent than among married couples as some studies have found that heavy drinking predicts subsequent aggression among dating couples (Foshee, Linder, MacDougall, & Bangdiwala, 2001; Magdol, Moffitt, Caspi, & Silva, 1998), whereas others have not (Gidycz, Warkentin, & Orchowski, 2007; Martino, Collins, & Ellickson, 2005; Testa, Livingston, & Leonard, 2003).

In addition to the effects of heavy drinking on subsequent dating violence, dating violence perpetration or victimization may influence future heavy drinking (Keller, El-Sheikh, Keiley, & Liao, 2009; Leonard & Senchak, 1996; Testa & Leonard, 2001; Testa, Livingston, & Leonard, 2003). In a drinking-to-cope model, individuals may drink to reduce negative affect or as a response to stress (Cooper, Russell, Skinner, Frone, & Mudar, 1992). Therefore, victims or perpetrators of dating violence may subsequently engage in heavy drinking as an attempt to cope with problems in the relationship (Testa & Leonard, 2001; Testa, Livingston, & Leonard, 2003) or because of the emotional consequences associated with dating violence perpetration or victimization (Anderson, 2002; Kilpatrick et al., 1997).

1.3. Mutual Dating Violence in Men and Women

Martino and colleagues (2005) argued that focusing specifically on victimization may not adequately reflect the relation between alcohol use and women’s experience of partner violence given that the majority of females categorized as victims also tend to perpetrate aggression against their partner (Hamberger, 1997; Vivian & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 1994; White & Chen, 2002). Capaldi and Owen (2001) reported that women were as likely as men to be violent, and that relationship partners were likely to match each other on whether or not they were violent. This is consistent with what Johnson (1995; p. 285) referred to as “common couple violence,” in which the more prevalent form of aggression in intimate relationships involves partners who are mutually aggressive.

The reciprocal effects of women’s heavy drinking and partner violence perpetration and victimization were examined in women between the ages of 23 and 29 (Martino, Collins, & Ellickson, 2005). The authors concluded that heavy drinking at age 23 did not predict partner violence victimization or perpetration at age 29, but that victimization at age 23 increased the risk for subsequent heavy drinking at age 29. Despite the use of a longitudinal design and the examination of the reciprocal effects of alcohol and partner violence, there are still several limitations of the Martino study. Most importantly, the assessment periods were six years apart, therefore limiting findings to the long-term effects of these behaviors rather than more immediate associations. In addition, the second assessment occurred when the women were 29 years old, which is beyond the age that partner violence typically peaks (O’Leary, 1999). Consequently, the lack of a significant association between alcohol use and subsequent partner violence may have been due to an overall decline in dating violent behaviors. Moreover, despite their suggestion that men and women are both perpetrators and victims of partner violence, the authors focused only on women. Thus, additional longitudinal studies are needed to investigate more immediate reciprocal associations between heavy drinking and perpetration and victimization of dating violence for both men and women.

1.4. Present Investigation

The aim of the present study was to examine the reciprocal effects of heavy drinking and physical dating violence perpetration and victimization across the first three years of college. We built upon the methodology used by Martino and colleagues (2005) by examining these reciprocal effects for both men and women using multiple assessments over a three year period allowing for a more thorough investigation of the dynamic relations between heavy drinking and dating violence. With a shorter time frame than the Martino study, our assessments also therefore may reflect more immediate associations between heavy drinking and dating violence.

Based on the alcohol myopia theory which suggests that individuals under the influence of alcohol will attend to the most salient cues in their environment and not the possible negative consequences, we hypothesized that heavy drinking would be positively and concurrently associated with dating violence for both women and men. We also anticipated that heavy drinking and dating violence would be longitudinally associated. Given that drinking tends to lead to aggression more generally, and dating violence specifically, we hypothesized that heavy drinking would predict future dating violence in the present investigation. Additionally, we hypothesized that dating violence would predict later heavy drinking due to a desire to reduce the negative affect associated with dating violence perpetration and victimization, or as an attempt to cope with the stress associated with relationship discord.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedures

Participants were drawn from a longitudinal study at The University of Texas at Austin, and the university’s Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures. Incoming college students from the 2004 entering class (N = 6,390) were invited to participate during their freshman orientation held the summer prior to college matriculation. At the time of recruitment, eligible participants were first time college freshmen, between the ages of 17 and 19, and unmarried (see Corbin, Vaughan, & Fromme, 2008, for a detailed explanation of the sample and recruitment procedures). Eligible participants were randomized to one of three study conditions,1 with 3,046 randomized to complete semi-annual assessments. Of those, 2,247 (73.8%; 59% female) provided informed consent and completed the initial high school survey. These participants were then invited to complete Internet-based surveys at the end of each fall and spring semester of college about their heavy drinking and dating violence perpetration and victimization for the previous 3-months (which maps on to the duration of the college semester). Participants were paid $20 for completing each fall semester survey and $25 for completing the spring semester surveys.

For the six semesters of data collection included in the current study (which corresponded to their first three years of college), response rates were high for all assessments, but declined over the course of the entire assessment period, ranging from 92.4% (n = 2,077) for the fall semester of the first year of college to 73.0% (n = 1,639) for the spring semester of the third year of college. At the time of the first college assessment, the mean age of the participants was 18.75 (SD=0.35), and the sample was 61% women with an average family income of approximately $58,000. The majority of the participants were White (54.2%), followed by Asian (18.0%), Hispanic (15.6%), African American (4.1%), and multiracial or other ethnicity (8.1%), which is similar to the ethnic distribution of the larger university community.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographics

Participants provided information on their age, sex, race and ethnicity, family’s annual income, and current relationship status.

2.2.2. Dating violence

The frequency of being a perpetrator or victim of minor and severe physical aggression with a dating partner during the 3 months prior to the completion of each semester survey was assessed using the Physical Assault subscale of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS-2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). The Physical Assault subscale has good internal reliability (alpha = .86; Straus et al., 1996). Participants were provided with a single question for minor and severe physical dating violence. Each question presented the stem “During the past 3 months, how many times have you or your boyfriend/girlfriend” and then listed the five minor aggression items from the CTS-2 Physical Assault Subscale (i.e., threw something at each other that could hurt, twisted partner’s arm or hair, pushed or shoved, grabbed, and slapped) and the seven severe aggression items (i.e., slammed partner against a wall, choked, kicked, punched or hit partner with something that could hurt, beat up partner, burned or scalded partner on purpose, used a knife or gun against partner). Each question was rated on a 7-point scale (0 = never, 1 = once, 2 = twice, 3 = 3–5, 4 = 6–10, 5 = 11–20, 6 = 20 or more). As suggested by Straus and colleagues (1996), the minor and severe items were scored using the midpoint of the range provided (a 25 was recommended for the ‘20 or more’ response option). The minor and severe physical aggression questions were significantly correlated at each assessment (r’s ranged from .157 to .741, all p’s < .01) and were summed for a total frequency of minor and severe physical dating violence for each assessment.

2.2.3. Heavy Drinking

Participants were asked about the number of episodes of binge drinking and frequency of drunkenness in the past three months. Binge drinking was assessed by asking participants to provide the number of episodes they had 5 or more drinks (for men) or 4 or more drinks (for women) per occasion (Wechsler & Isaac, 1992). Participants were then asked to provide the number of times they got drunk (not just a little high) on alcohol (Jackson, Sher, Gotham, & Wood, 2001). The responses for number of binge drinking episodes and frequency of drunkenness could range from 0–99 for each 3-month period. A combination of both objective and subjective measures of alcohol consumption has been suggested as a means to improve reliability over other assessments that rely on single-items (Sher & Rutledge, 2007). Therefore, a heavy drinking composite score similar to that used in previous research assessing the relation between heavy drinking and partner violence (Testa, Livingston, & Leonard, 2003) was created for each semester by adding the number of binge episodes (i.e., objective index) with the number of episodes of drunkenness (i.e., subjective index).

2.3. Analytic Strategy

We conducted chi-square analyses to evaluate gender and racial/ethnic differences from an initial Contact Form for those individuals who completed the initial survey and were therefore contacted to participate in the remainder of the surveys and those who agreed to be randomized to a study condition but failed to complete the initial survey. Next, missing data was examined in two ways, including an evaluation of individuals who had any missing data versus those who did not have any missing data, and individuals who dropped out of the study (and never re-entered) versus those who remained in the study. Specifically, chi-square analyses were conducted to examine differences on gender and race/ethnicity, and separate ANOVAs were run to determine differences on heavy drinking and dating violence from the initial college assessment.

The frequency of dating violence was examined and 5–7% of participants reported perpetration or victimization in the 3-months prior to each assessment. Because of relatively low base rates of occurrence, most studies assess intimate partner violence over a 12-month period (e.g., Martino et al., 2005; O’Farrell, Murphy, Stephan, Fals-Stewart, & Murphy, 2004; Schumacher, Homish, Leonard, Quigley, & Kearns-Bodkin, 2008; Testa, Livingston, & Leonard, 2003). The present study, however, used a 3-month time frame to map onto each college semester and to be consistent with the assessment of heavy drinking. Composite variables were therefore calculated for heavy drinking and dating violence by summing the fall and spring semesters for each year of data collection and used in all subsequent analyses.

Multi-group path analyses (Kline, 2005) for men and women were conducted with MPlus 5 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2007) to test the possible reciprocal relations between heavy drinking and dating violence frequency across the first three years of college. Among the advantages of MPlus is the use of maximum likelihood estimation procedures, which can effectively handle the non-systematic missing data in the current dataset (Kline, 2005). Multi-group path analyses allow for a model to be simultaneously fit to two separate groups; in the case of the current investigation, the same model was fit to men and women. First, the model was run constraining all direct paths to be equal for men and women, which assessed trends in the sample as a whole. Next, in order to compare the differences in the associations between heavy drinking and dating violence between men and women, a model was run in which the constraints were released and paths were allowed to vary freely for men and women. The relative fit of the model with unconstrained paths was compared to the fully constrained model using a Chi-square difference test. This comparison provided an examination of whether or not the associations between heavy drinking and dating violence were better understood by examining the total sample or by examining men and women separately.

Overall model fit was assessed by examining the Model Chi Square statistic. This index, however, may be erroneously significant when sample sizes are large, and other fit indices may provide more appropriate evidence of model fit (Kline, 2005). Therefore, we examined the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), which indicates reasonable fit with values between .05 and .08, and poor fit with values above .10 (Browne & Cudeck, 1993), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), which indicate reasonably good fit with values greater than .90 (Hu & Bentler, 1999), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) which indicates adequate fit with values less than .10 (Kline, 2005). Additionally, Hu and Bentler (1999) recommend a stringent joint criterion to retain a model, with CFI ≥ .96 and SRMR ≤ .10, to minimize the risk of a Type I or Type II error.

3. Results

3.1. Missing Data and Attrition Analyses

Overall, response rates were high with 95.7% of the total sample responding to at least one semester survey for Year 1, 88.3% for Year 2, and 80.3% for Year 3. Chi-square analyses between those who completed the contact form and agreed to be randomized to a study condition but did not complete the initial survey and those who completed the initial survey yielded a significant chi-square for gender, χ2(1, N = 3,022) = 46.77, p < .001, with a higher percentage of men (32.5%) who failed to complete the survey than women (21.5%). The analysis for race/ethnicity was not significant, χ2(7, N = 3,019) = 11.17, p = .13, indicating that race/ethnicity did not differ between those who completed the initial survey versus those who did not.

Chi-square and ANOVA analyses were conducted to examine differences between those individuals with missing data for at least one assessment (n = 887; 39.5%) and those with no missing data. The chi-square analyses were significant for gender, χ2(1, N = 2,247) = 45.89, p < .001, and race/ethnicity, χ2(7, N = 2,247) = 21.93, p < .01. Men (48.0%) were more likely to have missing data than were women (33.8%), and Hispanic (46.2%) and African American (45.2%) individuals were more likely to have missing data than were Caucasian (40.3%), Asian (31.0%), and Multi-ethnic or other (37.4%) individuals. Results of the ANOVA analyses revealed a significant main effect of heavy drinking, F(1, 2073) = 9.33, p < .01. Those with missing data were more likely to be heavier drinkers (M = 6.63, SD = 12.94) than those without missing data (M = 4.97, SD = 11.02). There were no significant group differences for dating violence, F(1, 2054) = 1.79, p = .18. A similar pattern of results was found for individuals who dropped out of the study (n = 386; 17.2%) versus those who remained in the study. Gender, χ2(1, N = 2,247) = 21.94, p < .001, and race/ethnicity, χ2(7, N = 2,247) = 16.32, p < .05, were significantly different between those who dropped out of the study versus those who remained in the study. Specifically, men (21.7%), Hispanics (20.2%), African Americans (19.4%) and Caucasians (18.2%) were more likely to drop out than women (14.1%) and Asians (11.1%). Additionally, the ANOVA for heavy drinking produced a significant main effect of group, F(1, 2073) = 7.95, p < .01; those who dropped out of the study were more likely to be heavier drinkers (M = 7.34, SD = 15.34) than those who remained in the study (M = 5.25, SD = 11.02). Again, there were no significant group differences for dating violence, F(1, 2054) = 0.3, p = .58.

3.2. Primary Analyses

Nineteen percent of the participants (n = 426; 73% female) experienced physical dating violence at some point during the three-year assessment period, with 10% in Year 1, 11% in Year 2, and 8.5% in Year 3. The prevalence of dating violence occurring in each of these assessment periods is lower than that reported in other studies (Testa, Livingston, & Leonard, 2003; Martino et al., 2005) and may be due to the fact that we did not assess these behaviors continuously for the entire 12-month period. Additionally, we included individuals who reported being single (i.e., did not endorse dating) in these analyses. Including individuals who endorsed being single is important in a college sample, as individuals may deny dating in the more traditional sense, but may engage in the current romantic relationship trends of “hooking up” or “seeing” other people (Bogle, 2007).

The means and standard deviations for men’s and women’s heavy drinking and dating violence frequency for the three years are presented in Table 1. Men and women differed significantly in their heavy drinking at Year 2 as well as their frequency of experiencing dating violence at Year 2, with men reporting heavier drinking than women, and women reporting a greater frequency of dating violence experiences than men. There were no differences, however, between heavy drinking and dating violence frequency for men and women at Years 1 or 3.

Table 1.

Means (and Standard Deviations) of heavy drinking and dating violence frequency.

| Observed Ranges |

Women | Men | t | Total Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 heavy drinking | 0 – 235 | 10.65 (20.85) | 12.12 (22.72) | −1.38 | 11.54 (21.44) |

| Year 2 heavy drinking | 0 – 180 | 11.92 (21.23) | 14.40 (23.85) | −2.53** | 12.60 (21.85) |

| Year 3 heavy drinking | 0 – 230 | 12.86 (22.02) | 15.29 (25.33) | −1.89 | 13.68 (23.29) |

| Year 1 dating violence | 0 – 50 | 0.49 (2.81) | 0.34 (2.06) | 1.39 | 0.47 (2.71) |

| Year 2 dating violence | 0 – 40 | 0.57 (2.85) | 0.26 (1.35) | 3.19** | 0.47 (2.42) |

| Year 3 dating violence | 0 – 50 | 0.37 (2.24) | 0.28 (1.73) | 1.063 | 0.33 (2.03) |

Note. All variables represent a composite of the fall and spring semester surveys in which participants reported on the past 3-months. Heavy drinking represents the number of binge episodes and the number of episodes of drunkenness. Dating violence frequency was rated on 7-point scales (0 = never, 1 = once, 2 = twice, 3 = 3–5, 4 = 6–10, 5 = 11–20, 6 = 20 or more) and were scored using the midpoint of the indicated range.

p < .01.

The bivariate correlations between heavy drinking and dating violence variables for men and women (Table 2) revealed significant associations among heavy drinking and among dating violence for both men and women across all three years. In addition, heavy drinking by men at Years 1 and 3 was significantly associated with dating violence at Year 1, whereas heavy drinking by women at Year 2 was significantly associated with dating violence at Year 3.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlation matrix with women on the upper diagonal and men on the lower diagonal.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Year 1 Heavy Drinking | – | .768** | .659** | .017 | .016 | .051 |

| 2. Year 2 Heavy Drinking | .730** | – | .773** | .026 | .024 | .065* |

| 3. Year 3 Heavy Drinking | .644** | .819** | – | .012 | .007 | .033 |

| 4. Year 1 Dating Violence Frequency |

.106* | .068 | .160** | – | .183** | .059* |

| 5. Year 2 Dating Violence Frequency |

−.011 | −.010 | .000 | .097** | – | .090** |

| 6. Year 3 Dating Violence Frequency |

.011 | .014 | .044 | .128** | .213** | – |

Note. p < .05;

p < .01.

3.2.1. Path Analyses

The concurrent and reciprocal associations between heavy drinking and dating violence were first examined for the sample as a whole by constraining all direct effects to be equal for men and women. Overall, the fully constrained model fit the data well, χ2 = 130.81, df = 16, p < .001; CFI = .97; TLI = .95; RMSEA = .08 (90% CI: .068-.093); SRMR = .04. Paths from earlier heavy drinking to later heavy drinking, and earlier dating violence to later dating violence, were significant indicating stability of heavy drinking and dating violence over time. The concurrent and longitudinal relations between heavy drinking and dating violence, however, were not significant.

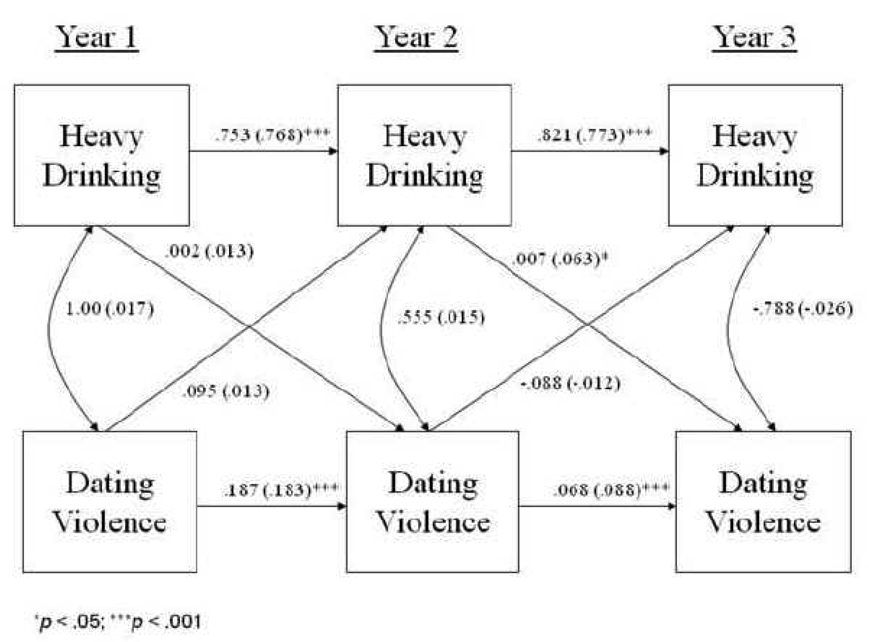

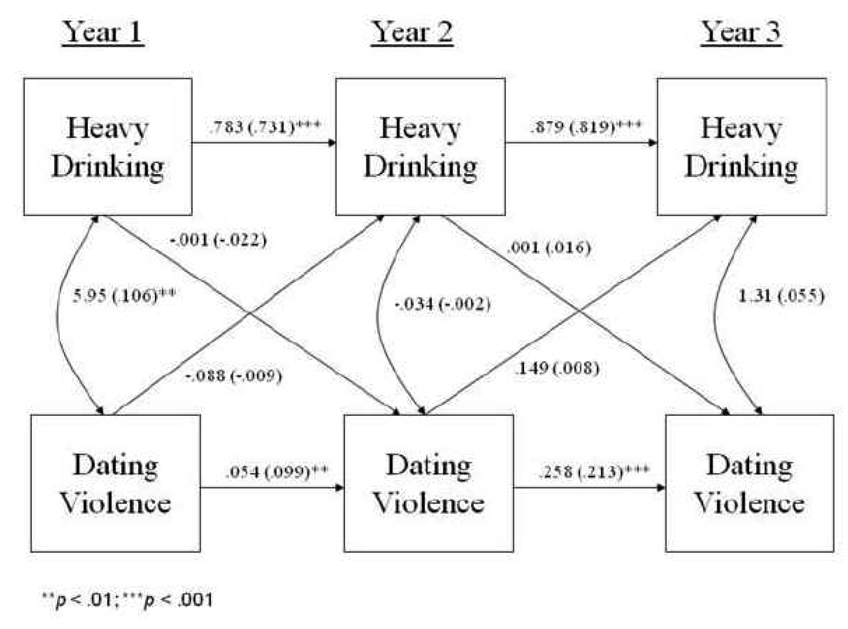

The fully unconstrained model, in which the paths are assessed separately for women and men, was run next and fit the data well, χ2 = 87.38, df = 8, p < .001; CFI = .98; TLI = .94; RMSEA = .09 (90% CI: .077-.112); SRMR = .03. Figure 1 and Figure 2 present the unstandardized path coefficients (and standardized coefficients in parentheses) of the fully unconstrained model for women and men, respectively. The associations across all time points for heavy drinking and dating violence were significant for both men and women suggesting that both heavy drinking and dating violence were stable across the three years. In addition, Year 2 heavy drinking was significantly positively associated with dating violence at Year 3 for women. For men, there was a significant concurrent association between heavy drinking and dating violence at Year 1. This fully unconstrained model fit the data better than the fully constrained model as indexed by a significant decrease in the chi-square goodness-of-fit indices, Δ χ2 = 43.43, Δ df = 8, p < .001. This suggests that the model in which paths are allowed to differ for men and women better characterizes the data than the model examining the total sample in which paths were constrained to be equal.

Figure 1.

Fully unconstrained path analysis model for women with unstandardized path coefficients (and standardized coefficients in parentheses).

Figure 2.

Fully unconstrained path analysis model for men with unstandardized path coefficients (and standardized coefficients in parentheses).

4. Discussion

The current study investigated the concurrent and reciprocal relations between heavy drinking and dating violence for men and women across the first three years of college. The frequency of heavy drinking and dating violence was found to be relatively stable across time for both genders. With the use of multi-group path analyses, we determined that the better fitting model was one that allowed the paths in the model to vary by gender, suggesting that the relation between alcohol use and dating violence over time differed for men and women.

Based on the alcohol myopia model, we hypothesized that alcohol would be positively associated with concurrent dating violence. This, however, was only supported for men and only during their freshman year of college. This finding may be due to the fact that aggressive behavior of heavy drinking individuals is disinhibited by their alcohol use (Curtin et al., 2001; Giancola, 2000; Steele & Josephs, 1990), or it may be that these men spent more time in situations where alcohol and aggression often co-occur (e.g., bars, large parties) during their freshman year. Consistent with a coping model, we also expected that dating violence would predict future heavy drinking in order to cope with negative feelings such as guilt over the aggression. Lastly, based on the idea that drinking leads to aggressive behaviors, we hypothesized that heavy drinking would predict future dating violence. These latter two hypotheses were not supported as instead heavy drinking during sophomore year predicted dating violence for women in their junior year, but no significant longitudinal associations were found for men.

It is somewhat surprising that heavy drinking did not predict subsequent dating violence for men; however, research in this area has not been consistent. At least one other study of heavy drinking and dating violence by men likewise failed to find an association over time even though they were related cross-sectionally (Foshee et al., 2001). Dating violence for men may be influenced more by the situational effects of heavy drinking, which would be consistent with a concurrent rather than a longitudinal association. Additionally, individuals in romantic relationships during college may not be as committed to their partners as married couples. Because heavy drinking has been associated with relationship discord or dissatisfaction (Testa, Livingston, & Leonard, 2003), these relationships may end before a pattern of dating violence develops.

The results of the current study also did not support earlier work which concluded that dating violence victimization and perpetration predicted future heavy drinking for women. These previous findings, however, represented either indirect effects through other relationship factors, or associations over a six-year period which represent more long-term effects than were investigated in the current study (Martino et al., 2005, Testa, Livingston, & Leonard, 2003). Substance use may be a way to cope with the negative consequences of dating violence (e.g., depression, PTSD); however, these effects may not be immediate, but rather develop over time, or may be related to the occurrence of other factors such as relationship dissatisfaction (Anderson, 2002; Kilpatrick et al., 1997).

It is important to note that heavy drinking was predictive of subsequent dating violence for women, with heavy drinking in sophomore year predicting dating violence during their junior year. This longitudinal relation may be explained by a tendency for heavy drinking women to associate with other heavy drinking individuals (for a review see Borsari & Carey, 2001). They may be more likely to form unhealthy relationships based on mutual abuse of alcohol (Leonard & Das Eiden, 1999; Leonard & Mudar, 2003) thereby increasing the likelihood of aggression occurring in the context of their dating relationships. Additionally, women who are drinking heavily may experience discord or dissatisfaction in their dating relationships. For those individuals who do not know healthy techniques to resolve conflicts in interpersonal relationships, a pattern of aggression consistent with common couple violence may begin (Johnson, 1995). Specifically, these dating partners may engage in verbal aggression as a result of relationship conflict that over time may lead to physical aggression (Schumacher & Leonard, 2005).

The current study improved upon the methodology from previous research by investigating the concurrent and reciprocal longitudinal associations between heavy drinking and dating violence across a three year period. Several limitations of the current study, however, should be noted. Heavier drinking individuals were more likely to fail to complete surveys or drop out of the study than individuals who were not heavy drinkers. This pattern, however, was not observed with respect to dating violence. Individuals who reported a greater frequency of dating violence were no more likely to have missing data or drop out of the study compared to those who did not report dating violence. Because heavy drinkers are more likely to engage in other aggressive behaviors including dating violence (e.g., Murray et al., 2008), missing data from these individuals may have resulted in lower estimates of dating violence. Relationship status was assessed at each semester survey, but it was not known whether aggression occurred with the same or different dating partners within and across assessment periods. Relationships during college, especially those that involve aggression, may be relatively brief, and could therefore influence any longitudinal relations between alcohol and aggression. If an aggressive relationship ended and participants were not in another romantic relationship during subsequent assessment periods, they had no opportunity for dating violence. Moreover, because the nature of relationships may change throughout the assessment period, the relation between alcohol and aggression may also change due to partner characteristics or how the couple handles conflict under the influence of alcohol. Additionally, these data were retrospective for the past 3-months, which may have influenced accurate reporting of heavy drinking and dating violence. Studies of both heavy drinking and intimate partner violence have demonstrated accurate recall for similar reference periods (Fals-Stewart, Birchler, & Kelley, 2003; Searles, Helzer, Walter, 2000). Future studies on heavy drinking and dating violence might include assessments that allow participants to report on behaviors for the previous day using daily monitoring procedures (e.g., Neal & Fromme, 2007) or interactive voice response (e.g., Parks, Hsich, Bradizza, & Romosz, 2008).

Another limitation of the current investigation is that we did not collect separate assessments of dating violence victimization and perpetration. Thus we cannot determine the frequency with which participants were the victim or the perpetrator of their dating violence experiences. Nevertheless, most aggressive dating relationships involve mutual aggression in which individuals are both perpetrators and victims (Capaldi & Owen, 2001; Johnson, 1995; Vivian & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 1994; White & Chen, 2002). Thus, the failure to distinguish these roles may be less important than identifying their mutual occurrence with heavy drinking. Additionally, a history of dating violence has been linked to current dating violence and drinking behaviors, but we did not assess dating violence prior to college. A more detailed history of dating violence would have facilitated our interpretation of the relations we observed, especially during the freshman year. It should also be noted that the findings presented in this investigation are specific to college samples and are not generalizable to young men and women more broadly. In addition, other forms of interpersonal aggression such as verbal aggression or sexual assault were not included in the current analyses; therefore, these results are only specific to the relation between heavy drinking and physical dating violence.

Limitations notwithstanding, the current study addressed a much-needed area for intimate partner violence by examining the longitudinal relation between heavy drinking and physical dating violence for both men and women. Although not found at every assessment period, dating violence and heavy alcohol consumption were concurrently associated for men, and heavy drinking predicted subsequent dating violence for women. Future studies should examine the contextual and relationship factors that may relate to the occurrence of dating violence. As Johnson (1995) suggested, there may be a pattern for partner violence that begins with a verbal argument and escalates by one or both partners to mild physical aggression. Event-level analyses would allow for an examination of these potential patterns as well as partner characteristics and relationship factors, such as satisfaction and commitment, which may influence the occurrence of dating violence.

Results of the current investigation provide important implications for interventions that target dating violence and heavy drinking. Efforts should be made to identify men and women who are drinking heavily and address their high level of alcohol consumption in order to prevent dating violence from occurring. Given the concurrent association between heavy drinking and dating violence for freshman men, education and intervention programs should target both of these harmful behaviors preferably prior to college matriculation. Specifically, programs should instruct men of the possibility that heavy drinking and dating violence can be associated and teach strategies to reduce the likelihood that either behavior will occur. Heavy drinking should be identified among women and targeted prior to or during their sophomore year of college to reduce the negative effects associated with heavy drinking, including the possibility of subsequent dating violence. Men and women should also be provided with information about how to establish and maintain healthy relationships, including effective ways to address conflict in dating relationships, and skills and support for ending unhealthy relationships.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: (1) Years 1–4 (n = 2,247) in which participants were invited to complete an initial high school survey, as well as semi-annual surveys occurring at the end of each semester, (2) Years 1 and 4 (n = 976) in which participants were invited to complete an initial high school survey as well as a survey in their fourth year of college, and (3) Year 4 only (n = 810) in which participants were invited to complete the survey in their fourth year of college only. In order to investigate the longitudinal relations for the first three years of college, only participants randomized to Years 1–4 are included in the present study.

References

- American Medical Association. Diagnostic and treatment guidelines on domestic violence. Chicago: Author; 1992. (No. AA 22:92–406 20M) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KL. Perpetrator or victim? Relationships between intimate partner violence and well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:851–863. [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:651–680. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias I, Samios L, O’Leary KD. Prevalence and correlates of physical aggression during courtship. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1987;2:82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bogle KA. The shift from dating to hooking up in college: What scholars have missed. Sociology Compass. 2007;1:775–788. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking: A review of the research. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2001;13:391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing Structural Equation Models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Owen LD. Physical aggression in a community sample of at-risk young couples: Gender comparisons for high frequency, injury, and fear. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:425–440. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.3.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascardi M, O’Leary KD, Lawrence EE, Schlee K. Characteristics of women physically abused by their spouses and who seek treatment regarding marital conflict. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:616–623. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Frone MR, Mudar P. Stress and alcohol use: Moderating effects of gender, coping, and alcohol expectancies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:139–152. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Vaughan EL, Fromme K. Ethnic differences and the closing of the sex gap in alcohol use among college-bound students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:240–248. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin JJ, Patrick CJ, Lang AR, Cacioppo JT, Birbaumer N. Alcohol affects emotion through cognition. Psychological Science. 2001;12:527–531. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr M, McDuff P, Wright J. Prevalence and predictors of dating violence among adolescent female victims of child sexual abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:1000–1017. doi: 10.1177/0886260506290201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W. The occurrence of partner physical aggression on days of alcohol consumption: A longitudinal diary study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:41–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Birchler GR, Kelley ML. The timeline followback spousal violence interview to assess physical aggression between intimate partners: Reliability and validity. Journal of Family Violence. 2003;18:131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, Golden J, Schumacher J. Intimate partner violence and substance use: a longitudinal day-to-day examination. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1555–1574. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foshee VA, Linder F, MacDougall JE, Bangdiwala S. Gender differences in the longitudinal predictors of adolescent dating violence. Preventive Medicine: An International Journal Devoted to Practice and Theory. 2001;32:128–141. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR. Executive functioning: A conceptual framework for alcohol-related aggression. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;8:576–594. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.4.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Warkentin JB, Orchowski LM. Predictors of perpetration of verbal, physical, and sexual violence: A prospective analysis of college men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2007;8:79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger LK. Female offenders in domestic violence: A look at actions in their context. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 1997;1:117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, O’Leary KD, Jouriles EN. Alcohol and aggressive personality styles: Potentiators of serious physical aggression against wives? Journal of Family Psychology. 1995;9:44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE. The drinking partnership and marital satisfaction: the longitudinal influence of discrepant drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:43–51. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SM. Issues in the dating violence research: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1999;4:233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Gotham HJ, Wood PK. Transitioning into and out of large-effect drinking in young adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:378–391. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.3.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP. Patriarchal terrorism and common couple violence: Two forms of violence against women. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Keller PS, El-Sheikh M, Keiley M, Liao P. Longitudinal relations between marital aggression and alcohol problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:2–13. doi: 10.1037/a0013459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Resnick HS, Saunder BE, Best CL. A 2-year longitudinal analysis of the relationships between violent assault and substance use in women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:834–847. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE. Domestic violence and alcohol: What is known and what do we need to know to encourage environmental interventions? Journal of Substance Use. 2001;6:235–247. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Das Eiden R. Husband’s and wife’s drinking: Unilateral or bilateral influences among newlyweds in a general population sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999 Supp 13:130–138. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1999.s13.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Mudar P. Peer and partner drinking and the transition to marriage: A longitudinal examination of selection and influences processes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:115–125. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Quigley BM. Drinking and marital aggression in newlyweds: An event-based analysis of drinking and the occurrence of husband marital aggression. Journal of Studies on Alcoholism. 1999;60:537–545. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Senchak M. Alcohol and premarital aggression among newlywed couples. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993 Suppl.11:96–108. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1993.s11.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Senchak M. Prospective prediction of husband marital aggression within newlywed couples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:369–380. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis SF, Fremouw W. Dating violence: A critical review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:105–127. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundeberg K, Stith SM, Penn CE, Ward DB. A comparison of nonviolent, psychologically violent, and physically violent male college daters. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19:1191–1200. doi: 10.1177/0886260504269096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthra R, Gidycz CA. Dating violence among college men and women: evaluation of a theoretical model. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:717–731. doi: 10.1177/0886260506287312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdol L, Moffitt T, Caspi A, Newman D, Fagan J, Silva P. Gender differences in partner violence in a birth cohort of 21-year-olds: Bridging the gap between clinical and epidemiological approaches. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:68–78. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdol L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Silva PA. Developmental antecedents of partner abuse: A prospective-longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:375–389. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino SC, Collins RL, Ellickson PL. Cross-lagged relationships between substance use and intimate partner violence among a sample of young adult women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:139–148. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Rivas MJ, Graña JL, O’Leary KD, González MP. Aggression in adolescent dating relationships: prevalence, justification, and health consequences. The Journal of adolescent health. 2007;40:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray RL, Chermack ST, Walton MA, Winters J, Booth BM, Blow FC. Psychological aggression, physical aggression, and injury in nonpartner relationships amng men and women in treatment for substance-use disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:896–905. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPlus User’s Guide. 5th ed. Las Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Neal DJ, Fromme K. Event-level covariation of alcohol intoxication and behavioral risks during the first year of college. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:294–306. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell TJ, Murphy CM, Stephan SH, Fals-Stewart W, Murphy M. Partner violence before and after couples-based alcoholism treatment for male alcoholic patients: The role of treatment involvement and abstinence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:202–217. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD. Developmental and affective issues in assessing and treating partner aggression. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1999;6:400–414. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Smith Slep AM. A dyadic longitudinal model of adolescent dating aggression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:314–327. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Hsich YP, Bradizza CM, Romosz AM. Factors influencing the temporal relationship between alcohol consumption and experiences with aggression among college women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:210–218. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernanen K. Alcohol in Human Violence. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Quigley BM, Leonard KE. Husband alcohol expectancies, drinking, and marital-conflict styles as predictors of severe marital violence among newlywed couples. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13:49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Quigley BM, Leonard KE. Alcohol and the continuation of early marital aggression. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:1003–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs D, O’Leary KD, Breslin F. Multiple predictors of physical aggression in dating couples. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1990;5:61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Homish GG, Leonard KE, Quigley BM. Longitudinal moderators of the relationship between excessive drinking and intimate partner violence in the early years of marriage. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:894–904. doi: 10.1037/a0013250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Leonard KE. Husbands’ and wives’ marital adjustment, verbal aggression, and physical aggression as longitudinal predictors of physical aggression in early marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:28–37. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searles JS, Helzer JE, Walter DE. Comparison of drinking patterns measured by daily reports and Timeline Follow Back. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:277–286. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.3.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Rutledge PC. Heavy drinking across the transition to college: Predicting first-semester heavy drinking from precollege variables. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:819–835. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shook NJ, Gerrity DA, Jurich J, Segrist AE. Courtship violence among college students: A comparison of verbally and physically abusive couples. Journal of Family Violence. 2000;15:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Smith DB, Penn CE, Ward DB, Tritt D. Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004;10:65–98. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA, Leonard KE. Women’s substance use and experiences of intimate partner violence: A longitudinal investigation among a community sample. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1649–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Quigley BM, Leonard KE. Does alcohol make a difference? Within-participants comparison of incidents of partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2003;18:735–743. doi: 10.1177/0886260503253232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Leonard KE. The impact of marital aggression on women’s psychological and marital functioning in a newlywed sample. Journal of Family Violence. 2001;16:115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Vivian D, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J. Are bi-directionally violent couples mutually victimized? A gender-sensitive comparison. Violence & Victims. 1994;9:107–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Isaac N. 'Binge' drinkers at Massachusetts colleges: Prevalence, drinking style, time trends and associated problems. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1992;267:2929–2931. doi: 10.1001/jama.267.21.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Chen P. Problem drinking and intimate partner violence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:205–214. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J, Koss M. Courtship violence: Incidence in a national sample of higher education students. Violence and Victims. 1991;6:247–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JW, Smith PH. Coveriation in the use of physical and sexual aggression among adolescent and college-age men: A longitudinal analysis. Violence Against Women. 2009;15:24–43. doi: 10.1177/1077801208328345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Ruggiero KJ, Danielson CK, Resnick HS, Hanson RF, Smith DW, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG. Prevalence and correlates of dating violence in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;47:755–762. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318172ef5f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]