Abstract

The most common mutation in the cystic fibrosis (CF) transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene, ΔF508, results in the production of a misfolded protein that is rapidly degraded. The mutant protein is temperature sensitive, and prior studies indicate that the low-temperature–rescued channel is poorly responsive to physiological stimuli, and is rapidly degraded from the cell surface at 37°C. In the present studies, we tested the effect of a recently characterized pharmacological corrector, 2-(5-chloro-2-methoxy-phenylamino)-4′-methyl-[4,5′bithiazolyl-2′-yl]-phenyl-methanone (corr-4a), on cell surface stability and function of the low-temperature–rescued ΔF508 CFTR. We demonstrate that corr-4a significantly enhanced the protein stability of rescued ΔF508 CFTR for up to 12 hours at 37°C (P < 0.05). Using firefly luciferase–based reporters to investigate the mechanisms by which low temperature and corr-4a enhance rescue, we found that low-temperature treatment inhibited proteasomal function, whereas corr-4a treatment inhibited the E1-E3 ubiquitination pathway. Ussing chamber studies indicated that corr-4a increased the cAMP-mediated ΔF508 CFTR response by 61% at 6 hours (P < 0.05), but not at later time points. However, addition of the CFTR channel activator, 4-methyl-2-(5-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)-phenol, significantly augmented cAMP-stimulated currents, revealing that the biochemically detectable cell surface ΔF508 CFTR could be stimulated under the right conditions. Our studies demonstrate that stabilizing rescued ΔF508 CFTR was not sufficient to obtain maximal ΔF508 CFTR function in airway epithelial cells. These results strongly support the idea that maximal correction of ΔF508 CFTR requires a chemical corrector that: (1) promotes folding and exit from the endoplasmic reticulum; (2) enhances surface stability; and (3) improves channel activity.

Keywords: cell surface trafficking, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, ΔF508 rescue, short-circuit current

CLINICAL RELEVANCE.

The most common mutation in cystic fibrosis, ΔF508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), results in the production of a misfolded protein that is rapidly degraded by the cell. Our studies focus on understanding the defect and determining methods for facilitating ΔF508 CFTR delivery to the cell surface where it can function as a chloride channel.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is caused by defects in the CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), a cAMP-regulated chloride channel that regulates ion and water balance across epithelia (1, 2). CFTR defects lead to altered exocrine secretion in a number of organ systems, including the airways, gastrointestinal track, pancreas, and sweat glands (1). Dehydrated mucus in the airways leads to chronic infections and eventual decline of lung function, and this phenotype is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality associated with CF (2).

Although more than 1,500 mutations have been identified in the CFTR gene (available at http://www.genet.sickkids.on.ca), the most common is the ΔF508 mutation. The misfolded gene product is recognized by the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) quality control machinery, retrotranslocated into the cytosol, and degraded through ER-associated degradation (ERAD) by the proteasome (3–7). Because of the severe nature of the processing defect, little if any ΔF508 CFTR reaches the apical cell surface, resulting in defective cAMP-dependent chloride conductance in the affected tissues.

Given that ΔF508 CFTR retains some biological activity (8), and that more than 90% of patients with CF have at least one allele of ΔF508 CFTR (9), there is considerable interest in understanding the molecular mechanisms controlling ΔF508 CFTR biogenesis and degradation. A number of interventions, including cell culture at low temperature (∼27°C) or treatment with chemical chaperones, such as glycerol, can rescue the mutant protein from ERAD and facilitate ΔF508 CFTR surface expression to some degree (10, 11). Therefore, an ongoing, concerted effort seeks to identify novel compounds that facilitate ΔF508 CFTR rescue from ERAD, increase surface stability, and improve channel function.

Other strategies for rescuing ΔF508 CFTR from ERAD have included sarcoplasmic ER Ca2+-ATPase inhibitors, such as curcumin and thapsigargin (12, 13), sodium 4-phenylbutyrate (14), and several small molecules identified through high-throughput screens (15–17).

It has been reported that two of the most effective corrector reagents, 2-(5-chloro-2-methoxy-phenylamino)-4′-methyl-[4,5′bithiazolyl-2′-yl]-phenyl-methanone (corr-4a) and 4-cyclohexyloxy-2-{1-[4-(4-methoxy-benzensulfonyl)-piperazin-1-yl]-ethyl}-quinazoline (vertex-325 [VRT-325]) may directly interact with ΔF508 CFTR (18, 19). Recent studies from our laboratory demonstrated that these compounds ablated the rapid endocytosis of low-temperature–rescued ΔF508 CFTR in polarized human airway epithelial cells (20), but the mechanism of action and the effects of these compounds on the long-term stability and chloride channel activity of ΔF508 CFTR are unclear.

In addition to compounds that facilitate ΔF508 CFTR biogenesis (rescue) and/or surface stability (e.g., correctors such corr-4a [15]), another group of compounds enhances ΔF508 CFTR channel activity (e.g., potentiators such as 4-methyl-2-(5-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)-phenol (VRT-532), which directly activate the channel [16]). Interestingly, VRT-532 has recently been shown to act as a corrector as well (18). To develop efficient therapies for CF caused by the ΔF508 mutation, it will be necessary to identify compounds that rescue ΔF508 CFTR from ERAD and correct the function of the mutant protein. Therefore, in the present study, we investigated how corr-4a alters the cell surface stability and function of ΔF508 CFTR in polarized CFBE41o-ΔF cells. Using firefly luciferase–based reporters of the ubiquitin-dependent proteasome system (UPS), we investigated the mechanism by which corr-4a enhances ΔF508 CFTR stability. We also followed the activity of rescued ΔF508 CFTR in the presence or absence of corr-4a for up to 12 hours. Because protein stability and function did not fully correlate, we investigated whether the addition of a potentiator could complement the stability effect of corr-4a. Our results suggest that corr-4a is not sufficient for maximal correction of the rescued protein. In other words, the ΔF508 CFTR on the cell surface is functionally compromised, and treating CF resulting from the ΔF508 mutation requires a combination of rescue, stabilization, and correction of the channel defect.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Lines and Cell Culture

Cells were maintained in a 37°C humidified incubator at 5% CO2 concentration. CFBE41o-ΔF (expressing ΔF508 CFTR) and CFBE41o-wild type (WT) (expressing WT CFTR) cell lines were developed and cultured as described previously (21). The nontransduced parental CFBE41o- cell line is homozygous for the ΔF508 mutation (22), but the endogenous ΔF508 CFTR expression is below detection, as monitored by RT-PCR or in Ussing chamber analysis (parental cells, present studies). CFBE41o- cell cultures were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagles medium) and Ham's F12 medium (50:50, vol/vol) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% (vol/vol) FBS. For experiments requiring polarized cells, CFBE41o-ΔF and CFBE41o-WT cells were seeded onto 6.5-mm Transwell filters (Costar, Corning, Acton, MA) for the Ussing chamber experiments, or on 24-mm Transwell filters for the surface biotinylation experiments. Cells were grown at a liquid–liquid interface, and media were changed every 24 hours. Under these conditions, the cells formed polarized monolayers with transepithelial resistances of greater than 1,000 Ω·cm2 after 4 days of culture.

Correctors and Potentiators of ΔF508 CFTR

Corr-4a (15) and VRT-532 (16) were provided by Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics (Bethesda, MD). Both compounds were dissolved in DMSO at a 10-mM stock concentration and diluted in OPTIMEM medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2% (vol/vol) FBS at 10 μM working concentration, as described previously (20). In all control experiments, DMSO was added to the same final concentration as a vehicle control. Drug treatments for all experiments were done for 12 hours, because longer time points dramatically decreased cell viability.

Immunoprecipitation

Immunoprecipitations were performed as described previously (20). Briefly, CFTR was immunoprecipitated from 500 μg (CFBE41o-WT cells) or 1,000 μg (CFBE41o-ΔF cells) of total protein using 1 μg/ml (final concentration) mouse monoclonal anti-CFTR C-terminal antibody (24-1, no. HB-11947; ATCC, Manassas, VA) coupled to 36 μl of protein G agarose beads (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Immunoprecipitation reactions were performed for 2 hours at 4°C. Immunoprecipitated proteins were in vitro phosphorylated and visualized by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography and phosphorimaging, or by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting (23).

Real-Time RT-PCR

Isolation of total cellular RNA and real-time RT-PCR were performed as described previously (24). Briefly, total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the ABI PRISM 7,500 sequence detection system as described in the ABI User Bulletin No. 2 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Total CFTR mRNA levels were evaluated using Assay-On-Demand primer mix (assay ID, Hs00357011_m1; Applied Biosystems). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA levels (assay ID, Hs99999905_m1; Applied Biosystems) were studied in parallel as an internal control. Results are expressed as CFTR mRNA levels relative to GAPDH mRNA (means ± SEM). Primer efficiencies for GAPDH and CFTR assays were 101% and 95%, respectively.

CFTR Cell Surface Half-Life Experiments

Cells were cultured at 27°C for 48 hours to facilitate ΔF508 CFTR rescue and delivery to the cell surface (20). The cells were then transferred to a 37°C incubator and cultured for 0 to 12 hours in the presence or absence of 10 μM corr-4a in OPTIMEM (Invitrogen) medium supplemented with 2% (vol/vol) FBS. Cell surface glycoproteins were biotinylated as described previously (23). CFTR was immunoprecipitated with a monoclonal antibody to CFTR (24-1) coupled to protein G agarose, run on 8% SDS-PAGE gels, and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Biotinylated CFTR was detected with horseradish peroxidase–labeled avidin. Chemiluminescence was induced with Pico Super Signal peroxide solution (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The membranes were exposed for time periods up to 1 minute, and a linear range for a standard set of diluted samples was calibrated as described previously (23). Western blots were analyzed and densities measured using IPLab (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) software. Data represent the results of more than three experiments.

Firefly Luciferase–Based Reporter Assays of the Ubiquitin-Dependent Degradation Pathways

HeLa ΔF cells grown on six-well plates were transfected with 0.5 μg plasmid DNA encoding one of the UPS reporters (25) in triplicates (see Table 1). At 30 hours after transfection, cells were transferred to 27°C culture and left untreated, or kept at 37°C and treated with 10 μM corr-4a for 12 hours in serum-free OPTIMEM. Untreated, transfected cells cultured at 37°C for 12 hours served as controls. All wells received fresh media (with or without corr-4a) every 2 hours. Firefly luciferase activities in cell lysates were measured using the Promega Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI), according to the manufacturer's protocol, on a TD-20/20 manual luminometer. For each condition, luciferase activity was expressed as the percent increase in luciferase activity compared with controls cultured at 37°C without corrector, and P values were determined using a paired, two-tailed Student's t test.

TABLE 1.

REPORTERS OF UBIQUITINATION-DEPENDENT DEGRADATION

| Reporter | Targeting Description |

|---|---|

| FL | Slow UPS degradation |

| CL-1-FL | Targeted to E1–E3 by CL1-degron, rapid degradation |

| 4-Ub-FL | Ubiquitinated, targeted to 26S, rapid degradation |

| p21-FL | Does not require ubiquitination, targeted to proteasome core by p21 |

Definition of abbreviation: UPS, ubiquitin-dependent proteasome system.

Ussing Chamber Studies

Tissue culture inserts were mounted in Ussing chambers (Jim's Instruments, Iowa City, IA) and bathed with normal Ringer solutions containing 120 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 3.3 mM KH2PO4, 0.83 mM K2HPO4, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 10 Hepes (Na+ free), 10 mM mannitol (apical compartment), and 10 mM glucose (basolateral compartment), as described previously (26). Bath solutions were vigorously stirred by bubbling continuously with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at 37°C (pH 7.4). Monolayers were short circuited (clamped) to 0 mV, and short-circuit currents (Isc) were measured using a voltage clamp (VCC-600; Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA). A 10-mV pulse of 1-second duration was imposed every 10 seconds to monitor transepithelial resistance (Rt), which was calculated using Ohm's law. Data were collected using the Acquire and Analyze program (version 1.45; Physiologic Instruments). After establishment of steady-state values of Isc and Rt (usually within 5–10 min from mounting the filters to the Ussing chambers), normal Ringer's solution in the apical side of chambers was changed for low-chloride (5 mM Cl− solution containing 120 mM C6H11O7Na, 1.2 mM C12H22CaO14, and 1.2 mM C12 H 22MgO14). The basolateral side was maintained at 125 mM Cl−. Amiloride 0.1 mM was added to the apical side, and DMSO or corr-4a (10 μM) were added into the apical compartments. Isc and Rt were measured continuously until a new steady state was reached. Basolateral membranes were then permeabilized by the addition of amphotericin B (100 μM). Permeabilization was followed by a drop in Rt. CFTR was stimulated as described for each experiment. Forskolin (FSK; Calbiochem, Gibbstown, NJ) was used at 10 μM, genistein (GEN; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at 50 μM, and VRT-532 at 10 μM final concentration in the apical chambers. Currents were blocked using CFTRinh-172 (2-thioxo-4-thiazolidinone analog; Calbiochem) at 10 μM final concentration for WT CFTR and 100 μM final concentration for ΔF508 CFTR.

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as means (±SEM), and statistical significances were calculated by using the two-tailed Student's t test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Corr-4a–Mediated Rescue of ΔF508 CFTR in Human Airway Epithelial Cells

In order to follow the trafficking of rescued ΔF508 CFTR at the cell surface, we first determined the effects of corr-4a on ΔF508 CFTR biogenesis in human airway epithelial cells (CFBE41o-ΔF). We treated polarized CFBE41o-ΔF cells with varying concentrations of corr-4a for 12 hours at 37°C. Longer treatments with the compound resulted in significant cellular toxicity (data not shown). Although we tested a wide range of concentrations for corr-4a (0.1–80 μM), the efficiency of ΔF508 CFTR rescue was very limited (Figure 1 and data not shown). Concentrations below 1 μM had no effect, whereas the most effective concentrations were in the 2.5–10 μM range. Therefore, for our studies, we used 10 μM corr-4a throughout.

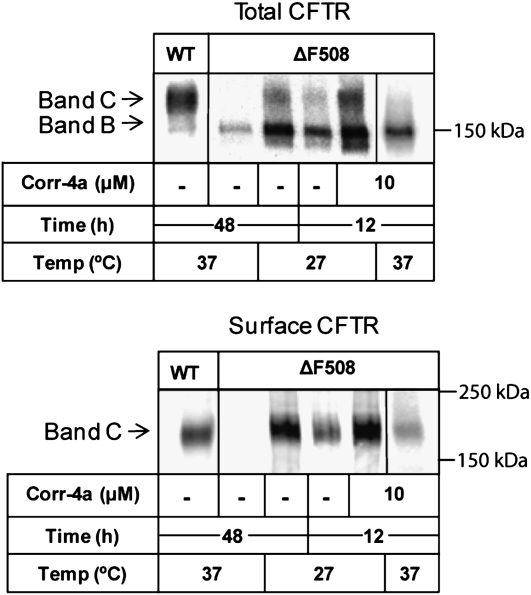

Figure 1.

Chemical chaperone rescue of ΔF508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) in human airway epithelial cells. Polarized CFBE41o-ΔF cell monolayers were treated with 10 μM 2-(5-chloro-2-methoxy-phenylamino)-4′-methyl-[4,5′bithiazolyl-2′-yl]-phenyl-methanone (corr-4a) for 12 hours at 37°C. The cells were then surface biotinylated, and CFTR was immunoprecipitated from 500 μg of cell lysate. The lysate was split into two fractions and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting for total CFTR (upper panel) and surface CFTR (lower panel) using anti-CFTR antibodies or avidin– horseradish peroxidase, respectively. Control samples included CFBE41o-WT (WT CFTR) grown at 37°C, CFBE41o-ΔF cells maintained at 37°C, CFBE41o-ΔF grown at 27°C for 48 hours (low-temperature correction), and CFBE41o-ΔF grown at 27°C for 12 hours with or without 10 μM corr-4 treatment. A representative gel of three is shown.

After treatment, CFTR was immunoprecipitated from whole-cell lysates and analyzed for the presence of mature, fully glycosylated protein, or band C. Cell surface ΔF508 CFTR levels were determined after cell surface biotinylation. The results in Figure 1 indicate several points. Low-temperature rescue for 12 hours is more effective than treatment with corr-4a in CFBE41o-ΔF cells (Figure 1, lane 4 versus lane 6). Corr-4a plus low temperature had an additive effect (lane 5). Low-temperature and corr-4a treatment likewise increased both the immature (band B) and mature forms of CFTR (band C). The appearance of band C correlated with the appearance of a surface biotinylated pool (Figure 1, lower panel). A 48-hour low-temperature treatment was much more effective and reproducible than corr-4a treatment in the CFBE41o-ΔF cells, and therefore, for all subsequent studies, we used low-temperature correction for 48 hours to deliver ΔF508 CFTR to the cell surface. To analyze the effects of corr-4a on cell surface trafficking and function, we returned cells to 37°C, and added the compound to the culture media for the time periods specified.

Addition of corr-4a for 1 Hour Does Not Improve the Function of Low-Temperature–Rescued ΔF508 CFTR

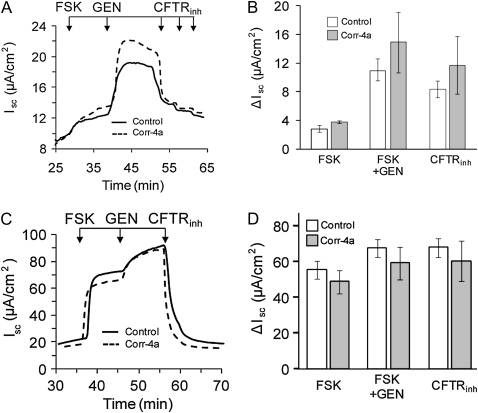

Previous reports indicated that low-temperature–rescued ΔF508 CFTR was poorly responsive to cAMP-mediated stimuli (21). In the present studies, we used Ussing chambers to compare the functional activity of rescued ΔF508 with WT CFTR in the presence or absence of corr-4a at 37°C. To begin testing the effects of corr-4a on ΔF508 CFTR function at 37°C, we included a 1-hour pretreatment with corr-4a for the last hour at 27°C. This pretreatment was sufficient to stabilize the surface pool of ΔF508 CFTR in our previous studies (20). To ensure that the monitored Isc could be attributed to CFTR, we applied the following conditions: (1) Isc was measured after permeabilization of the basolateral membranes with amphotericin B; (2) tracings were recorded in the presence of amiloride, which blocks epithelial sodium channels; (3) the effects of FSK, GEN, and a specific CFTR inhibitor (CFTRinh-172) were all tested (27, 28); (4) Isc was also monitored in the parental CFBE41o- cells, which do not express detectable levels of CFTR mRNA.

Ussing chamber assays were prepared and executed at 37°C, and the analysis was done as quickly as possible, as ΔF508 CFTR is rapidly degraded from the cell surface under these conditions (20, 29–31). The time at 37°C before the FSK stimulation and after permeabilization was roughly 30–40 minutes (0 time point). Under these conditions, the FSK-stimulated Isc for ΔF508 CFTR (Figures 2A and 2B) was only about 5% of WT currents (Figures 2C and 2D). Although both the FSK- and FSK-plus-GEN–activated Iscs were slightly greater in the presence of corr-4a, these trends toward improvement did not reach statistical significance. In the CFBE41o- cells (CFBE parental, Figures 2E and 2F), there was no FSK-stimulated activity, supporting the view that the FSK-stimulated currents in CFBE41o-ΔF cells were due to rescued ΔF508 CFTR. The significant Isc response to UTP, which activates P2Y receptors, indicates that the cells were viable under our experimental conditions (Figures 2E and 2F).

Figure 2.

Ussing chamber analysis of ΔF508 and WT CFTR after low-temperature correction. (A and B) CFBE41o− ΔF, (C and D) CFBE41o− WT, and (E and F) CFBE41o− parental cell monolayers were cultured at 27°C for 48 hours and studied in Ussing chambers at 37°C, as described in Materials and Methods. Under low chloride (1.2 mM NaCl, 115 mM Na gluconate), and 100 μM amiloride in the apical chamber, the basolateral membranes of the monolayers were permeabilized with amphotericin B (100 μM). After reaching baseline steady-state short-circuit currents (Isc), the monolayers were treated sequentially with forskolin (FSK; 10 μM), genistein (GEN; 50 μM), and CFTRinh-172 (three sequential additions: 20 + 20 + 60 μM). Representative tracings are shown on the left, and the summaries of the experiments are plotted on the right. Pretreatment of the cell monolayers during the last 1 hour at 27°C with corr-4a had no significant effect on the ΔISC compared with control (treated with 0.01% DMSO). The FSK responses of control ΔF508 CFTR–expressing monolayers were approximately 5% of the WT CFTR–expressing responses (B and D; [open bars], n = 11; 2.9 ± 0.46 versus 55.2 ± 5.12 mA/cm2, respectively), whereas the FSK responses of the corr-4a–treated ΔF508 CFTR–expressing monolayers were 8% of the WT responses (B and D [gray bars]; n = 8–10; 3.66 ± 0.19 versus 48.49 ± 6.6 mA/cm2, respectively). The CFBE41o− parental cell line (E and F) did not respond to FSK treatment, but UTP (100 μM) produced a response, indicating that alternative channels had been activated (n = 4). Relative CFTR protein levels (G) and message levels (H) are shown for the CFBE41o− WT, CFBE41o− parental, CFBE41o− ΔF, HeLa-ΔF, and HeLa parental cells. CFTR protein was immunoprecipitated from 500 μg total cellular proteins using 24-1 (an anti–C-terminal antibody), in vitro phosphorylated using γ32P ATP, protein kinase A (PKA), separated on 6% SDS-PAGE, and detected using Phosphorimager analysis. CFTR mRNA levels are plotted relative to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. CFTR mRNA levels in HeLa-ΔF and HeLa parental cells were measured as positive and negative controls, respectively. The results are given as means (±SD) (n = 4; * P < 0.005).

To confirm the presence of CFTR in each of the cell lines, we determined protein and mRNA levels. CFTR was immunoprecipitated from CFBE41o-WT, CFBE41o-parental, and CFBE41o-ΔF cells, and compared with HeLa-parental and HeLa-ΔF cells (Figure 2G). WT CFTR appeared as core glycosylated band B and fully glycosylated band C (Figure 2G, lane 1). There was no detectable CFTR in CFBE41o- parental cells (Figure 2G, lane 2). ΔF508 CFTR was seen as the immature band B form in CFBE41o-ΔF cells (Figure 2G, lane 3), identical to ΔF508 CFTR expressed in HeLa-ΔF cells (Figure 2G, lane 4).

CFTR mRNA levels were measured with real-time RT-PCR. The results shown in Figure 1H indicate that ΔF508 CFTR mRNA levels in CFBE41o-ΔF cells were higher than WT CFTR message levels in CFBE41o-WT cells, and, therefore, the dramatic differences in the current profiles could not be attributed to enhanced WT CFTR mRNA levels. Furthermore, ΔF508 mRNA was undetectable in the CFBE41o- parental cell line, supporting the idea that these cells lack endogenous ΔF508 CFTR, and, therefore, the currents demonstrated in Figures 1A and 1C can be directly attributed to CFTR function at the cell surface.

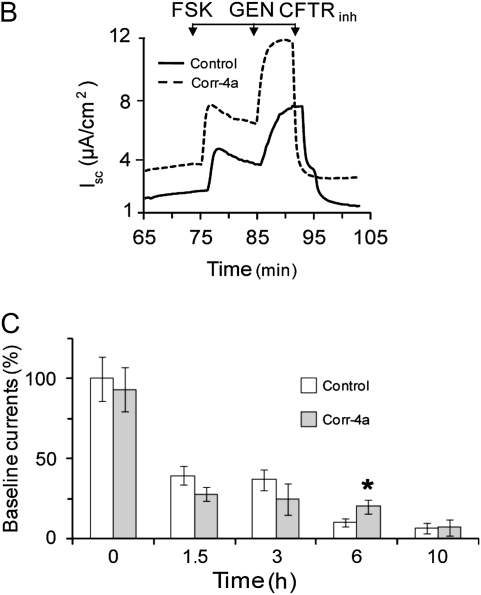

Extended Treatment with corr-4a of Low-Temperature–Rescued CFBE41o-ΔF Cells Stabilizes the Function of ΔF508 CFTR at 37°C

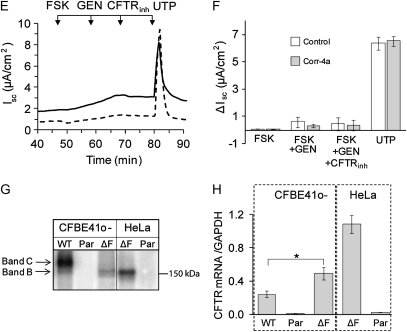

To test the effects of corr-4a on the channel activity of rescued ΔF508 CFTR, cells were preincubated at 27°C for 48 hours and then removed, and cultured at 37°C for the additional time points specified (1.5, 3, 6, and 10 h) in the presence or absence of corr-4a (10 μM). Ussing chamber analysis of these cultures revealed a significant increase in the FSK-stimulated currents of corr-4a–treated monolayers at 6 hours, but, by 10 hours, the difference between the corr-4a–treated and untreated monolayers was gone (Figure 3A). Neither the FSK-plus-GEN–activated currents nor the CFTRinh-172 inhibitor effects were different in control and corr-4a–treated cells at any of the time points tested (Figure 3A). A representative tracing of the 6-hour time point is shown in Figure 3B. A point worth mentioning is that the baseline currents (e.g., prestimulation currents) were dramatically lower in corr-4a–treated monolayers at 6 hours than they were at the 0 time point (10.4 ± 2.5% [control] versus 19.8 ± 4% [corr-4a treated]) (Figure 3C). To determine if the differences in baseline currents could be attributed to differences in CFTR activity, we added CFTRinh-172 to the chambers before FSK stimulation and found that the baseline currents at 6 hours decreased in both the control and corr-4a–treated monolayers, with a correspondingly greater decrease in current in the corr-4a–treated samples (data not shown). This supports the hypothesis that CFTR participates in basal ion transport, and that the elevated baseline currents in corr-4a–treated cells were due to enhanced levels of functional CFTR. Because both the FSK-stimulated and the baseline currents returned to control levels in corr-4a–treated monolayers by 10 hours, these data suggest that the effect of the corrector on Iscs was no longer present at the 10-hour time point.

Figure 3.

Functional stability of low-temperature–rescued ΔF508 CFTR at 37°C in the presence of corr-4a. CFBE41o− ΔF cells were treated as described in Figure 1, but were cultured for 0–10 hours at 37°C in the presence or absence (Control) of corr-4a before Ussing chamber analysis. The experiments were performed as described in Figure 2. The Isc change is shown in A for different time points indicated (0, 1.5, 3, 6, and 10 h) after FSK stimulation (FSK), after FSK and GEN stimulation (FSK + GEN), and after CFTR-172inh inhibition (CFTRinh). (B) A representative tracing for the 6-hour time point. In C, the baseline currents were compared with controls (0 time point after 27°C rescue = 100). The FSK-stimulated Isc at 6 hours (A: 2.3 ± 0.46 μA/cm2 versus 3.7 ± 0.5 μA/cm2 at 6 h; n = 10; P < 0.05) and the baseline currents (C: 10.4 ± 2.4% versus 20.2 ± 4.2% of the currents at 0 time; n = 7–12; P < 0.05) of the corr-4a–treated CFBE41o− ΔF cells were significantly different from the controls.

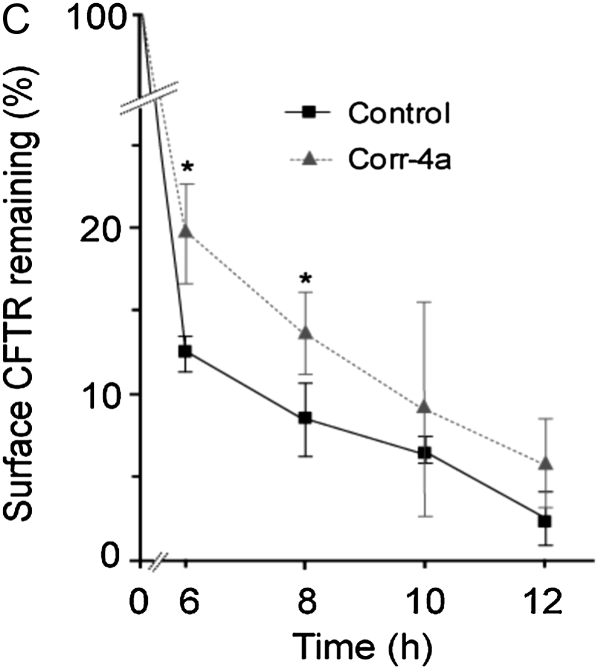

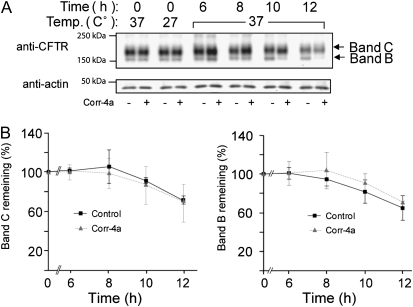

Corr-4a Increases the Protein Stability of ΔF508 CFTR at 37°C

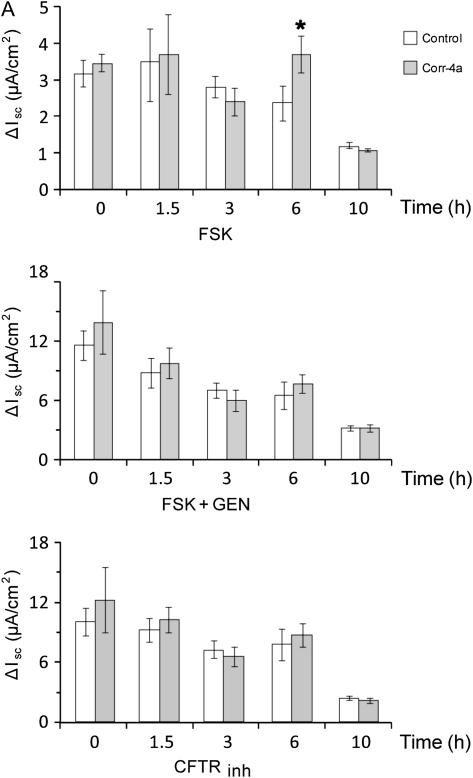

To determine the effects of corr-4a on ΔF508 CFTR protein levels, we monitored total CFTR levels (bands B and C), and also followed the surface pool of ΔF508 CFTR using surface biotinylation. Surprisingly, these studies revealed that corr-4a stabilized both the immature and the maturely glycosylated forms (bands B and C) for up to 12 hours at 37°C (Figures 4A and 4B). Analysis of the surface CFTR pool (biotinylated fraction) indicated a significant increase in corr-4a–treated cells at 6 and 8 hours (Figures 4A and 4C). Taken together, the functional and biochemical studies confirm the hypothesis that corr-4a stabilizes rΔF508 CFTR. Importantly, even in the presence of corr-4a, the surface pool of rΔF508 CFTR decreased to less than 10% after 12 hours, suggesting that corr-4a–mediated rescue/correction of ΔF508 CFTR is short-lived.

Figure 4.

Corr-4a stabilizes ΔF508 CFTR. Polarized CFBE41o− ΔF cells were cultured at 27°C for 48 hours. Cells were then transferred to 37°C and treated with corr-4a or vehicle for various times up to 12 hours. Cells cultured at 37°C were tested as control (0 time, 37°C). Total CFTR levels were analyzed after immunoprecipitation and Western blotting. Cell surface CFTR levels were measured after cell surface biotinylation. (A) A representative gel illustrates total CFTR levels (top panel). Bands B and C are marked with arrows. Actin levels are shown as a loading control (middle panel). Cell surface CFTR levels are shown in the lower panel at the same time points as total CFTR levels. Representative gels of three or more experiments are shown. (B) Quantification of total CFTR. Band C and B levels were calculated by densitometry (n = 5). Band C expression was significantly higher in corr-4a–treated samples at 6 hours (P = 0.03; 16.36 ± 3 versus 24.6 ± 0.5 [% remaining]), 8 hours (P = 0.02; 9 ± 1.9 versus 15.5 ± 3.3), and 10 hours (P = 0.02; 6 ± 2.2 versus 12.3 ± 3.6). Band B expression was higher at 10 and 12 hours (* P < 0.05). (C) Quantification of cell surface CFTR. Surface ΔF508 CFTR expression was significantly higher in corr-4a–treated cells at 6 hours (P = 0.04; 12.5 ± 1 and 19.8 ± 2.9) and at 8 hours (P = 0.04; 8.5 ± 2.3 and 13.8 ± 2.4).

We also observed that corr-4a had the most dramatic effect on the stability of band B. The amount of band B was still 34.6 (±7.6)% of the 0 time point after 12 hours in the corrector-4a–treated samples, compared with 9.0 (±2.0)% in the control samples (Figure 4B, right panel). Although the fully processed band C decreased to 13.3 (±5.5)% in the presence of corr-4a by 12 hours, the effect on the cell surface stability of the rescued ΔF508 CFTR was still significant (Figure 4B, left panel).

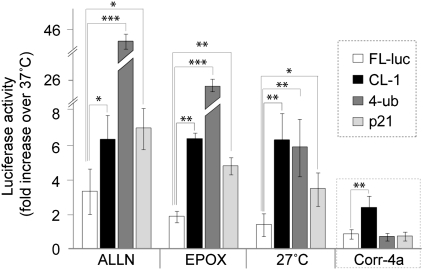

Low Temperature and corr-4a Inhibit Distinct Steps of the Ubiquitin-Mediated Degradative Pathways

The increases in CFTR (both band B and C) levels in the presence of corr-4a suggests that corr-4a inhibited protein degradation. Previous studies have suggested that ΔF508 CFTR in the ER and ΔF508 CFTR at the cell surface are degraded by different pathways, both of which are ubiquitin dependent: ubiquitin-dependent ERAD is responsible for band B degradation, and rescued ΔF508 CFTR is degraded from the cell surface through a ubiquitination-dependent lysosomal pathway. Therefore, we designed studies to test which steps of the ubiquitin-dependent degradative pathway were involved in ΔF508 CFTR degradation using three firefly luciferase–based reporters of the UPS, as described previously (Table 1) (25). A fourth firefly luciferase construct that did not contain a UPS reporter tag (FL-luc) was also tested as a control. The product of the CL-1-FL construct containing a 16–amino acid degron sequence was designed to monitor the E1–E3 ubiquitination machinery (32, 33). The 4-Ub-FL construct contains four in-frame ubiquitin sequences. Therefore, the product of this construct is suitable to monitor the degradation of a protein that has already been modified by ubiquitin (25). The p21-FL construct produces a UPS substrate that undergoes rapid degradation by the 20S proteasome without being ubiquitinated (34–39). Therefore, the latter two constructs should give information about the activity of the 26S and 20S proteasomes, respectively, independent of the ubiquitin conjugation activity of the cell.

To confirm the functionality of the constructs, we tested the effects of two proteasome inhibitors on luciferase activity in cells expressing each of the constructs (Figure 5). The results demonstrate that culturing cells expressing the constructs in the presence of ALLN (50 μM) or epoxomycin (0.5 μM) increased the luciferase activity more than 5-fold for the CL-1-FL, 4-Ub-FL, and p-21-FL constructs compared with untreated controls. Interestingly, culturing the cells at 27°C also dramatically increased the luciferase activities from all three constructs, indicating that low temperature inhibits proteasome function. In contrast, corr-4a treatment increased luciferase activity only in cells transfected with CL-1-FL, the construct that requires ubiquitination before degradation. Corr-4a did not inhibit the degradation of the constructs that do not require ubiquitination for proteasomal degradation, indicating that corr-4a has no direct inhibitory effect on the proteasome. These results strongly support the idea that corr-4a inhibits the E1–E3 ubiquitination pathway, and explains the increased stability of the band B form of ΔF508 CFTR in the corr-4a–treated samples.

Figure 5.

Low-temperature and corr-4a effects on the ubiquitin–proteasome system. HeLa cells were transfected with luciferase (FL-luc), a luciferase construct with a degron sequence added (CL-1), a luciferase construct with four in-frame ubiquitin sequences at the N terminus (4-ub), or with a luciferase construct containing a C-terminal sequence of p21 that targets proteins to the proteasome without ubiquitin modification (see Table 1). Luciferase activity for each construct was normalized to light units measured in control (untreated) cells cultured at 37°C (onefold). The increases in luciferase activity are fold increases (n = 3; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001).

WT CFTR Is Unaffected by corr-4a Treatment

Because corr-4a inhibits ΔF508 CFTR and CL-1-Fl degradation, we tested whether corr-4a has any effect on the degradation of WT CFTR from the cell surface. Because ΔF508 CFTR–expressing cells were subjected to low-temperature culture to deliver ΔF508 CFTR to the cell surface, we treated the WT CFTR–expressing cells to identical low-temperature culture conditions as well. During the last hour of low-temperature culture, we treated cells with 10 μM corr-4 or vehicle, and extended the treatment at 37°C for up to 12 hours. We then examined the WT CFTR bands C and B levels over time. The results indicate that corr-4a treatment produced no significant changes in WT CFTR levels. We measured slightly more band B after 8 hours in the corr-4a–treated samples than in the control samples in some experiments (Figure 6A), although the effect was not significant (Figure 6B). Importantly, there was no change in WT CFTR band C levels in the corr-4a–treated cells. This supports the idea that corr-4a inhibits ubiquitination-dependent degradation at the ER, but has no effect on the ubiquitination-independent lysosomal degradation of the cell surface–localized WT CFTR.

Figure 6.

Stability of low-temperature–rescued WT CFTR at 37°C in the presence of corr-4a. CFBE41o− WT cells were treated and analyzed as the CFBE41o− ΔF cells shown in Figure 4. (A) Total CFTR (anti-CFTR) and loading controls (actin) are shown. Representative gels of three are shown. (B) Quantitation of WT CFTR band C and B levels are shown.

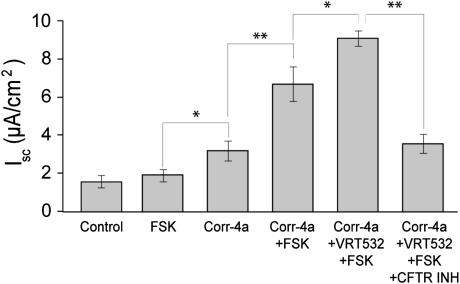

The Presence of a CFTR Potentiator Enhances the Effect of corr-4a

Corr-4a stabilized both the mature and immature forms of ΔF508 CFTR for up to 12 hours in biochemical assays; however, in Ussing chamber analysis, we measured significant changes in the FSK-stimulated activity only at the 6-hour time point. These results suggest that the increased protein stability did not necessarily reflect corrected channel function. To test this hypothesis, we repeated the 6-hour corr-4a exposure experiments, this time conducting the Ussing chamber analysis in the presence of a known channel potentiator, VRT-532. In agreement with our previous results (Figure 3), both the baseline and the FSK-stimulated currents increased significantly in corr-4a–treated cells. More importantly, the presence of VRT-532 in the bathing fluid further enhanced the FSK-stimulated currents (Figure 7). We noted no additional effects in the presence of GEN, supporting the idea that, in the presence of VRT-532, ΔF508 CFTR could be maximally activated by cAMP. We could block the FSK-plus-VRT-532–activated currents with CFTRinh-172, indicating that the currents were CFTR mediated. These results confirm our previous finding, that, although corr-4a enhances both the protein stability and function of ΔF508 CFTR, the channel is still compromised, and requires a potentiator for maximum channel activity.

Figure 7.

Increases in the functional activity of corr-4–treated ΔF508 CFTR–expressing CFBE41o− cells with 4-methyl-2-(5-phenyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)-phenol (VRT-532). CFBE41o− ΔF CFTR–expressing cells were temperature corrected (48 h at 27°C) and cultured at 37°C for 6 hours in the presence or absence (Control) of corr-4a. The baseline currents were higher in the corr-4a–treated cells (Corr-4a) than in the control. Iscs in the presence of the potentiator, VRT-532, were enhanced during FSK activation (corr-4a, VRT-532, FSK) (n > 6; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

In vivo and in vitro studies have suggested that enhancing ΔF508 CFTR activity by as little as 5% may diminish the symptoms of CF (2, 40, 41). Therefore, a major thrust of CF research has been directed at identifying and characterizing small molecules that facilitate ΔF508 CFTR rescue from ERAD. Previously, we established that two of these correctors, corr-4a and VRT-325, stabilized the surface pool of ΔF508 CFTR by inhibiting endocytosis (20). In the present study, we focused on the mechanism by which corr-4a rescues and stabilizes ΔF508 CFTR, and the functionality of the rescued protein in the presence and absence of corr-4a. We asked the following questions: (1) Do low-temperature culture and corr-4a use the same mechanism to rescue ΔF508 CFTR? (2) How long after delivery to the cell surface can ΔF508 CFTR be activated by physiological stimuli, such as FSK, in the presence or absence of corr-4a? (3) Do cell surface ΔF508 CFTR levels correlate with physiological activity in the presence of corr-4a?

Although the effects of low temperature on ΔF508 CFTR have been established for quite some time (10, 20, 31, 42, 43), the mechanism by which low temperature facilitates ΔF508 CFTR exit from the ER is not clear. The simplest interpretation is that, at lower temperature, the channel folds properly and is competent to exit the ER. However, if that is true, why is the majority of protein retained in the ER, and why is the function of the rescued cell surface ΔF508 CFTR compromised? One possibility is that only a small percentage of the protein is properly folded and rescued. However, if this were true, the functionality and stability of the rescued protein should be comparable to the wild type. Our results suggest that corr-4a stabilizes ΔF508 CFTR, yet the channel activity is still compromised. These results are consistent with those of Cui and coworkers (44), who showed that ΔF508 plays a direct role in channel gating and residency time in the closed state. The other possibility is that some partially folded protein escapes ERAD, because the components or the pathways of the quality control machinery are altered. To support this possibility, our results indicate that both low-temperature culture and corr-4a increase the level of ΔF508 CFTR band B. Furthermore, both conditions alter the function of the ubiquitin-dependent degradative pathways. Using luciferase-based reporter constructs, we found that low-temperature culture inhibited both the E1–E3 cascade and the function of the proteasome. In contrast, corr-4a only inhibited the E1–E3 cascade. Therefore, it is likely that inhibition of the E1–E3 cascade by corr-4a is responsible for the stabilization ΔF508 CFTR at both the ER and the cell surface. Although we did not monitor the ubiquitination levels directly for WT or ΔF508 CFTR, there is also the possibility that corr-4a treatment interferes with the delivery of the ΔF508 CFTR to the degradative compartment as the result of inhibited ubiquitination. Interestingly, attempts by us and others to rescue ΔF508 CFTR using proteasome inhibitors have not been successful, although inhibition of the proteasome does stabilize the B band (4, 6, 45) and cell surface CFTR in other models (31). More recent results have indirectly suggested that selective inhibition of ERAD may rescue ΔF508 CFTR in CF tracheal epithelial cells transfected with ΔF508 CFTR (46). Considering these data, and that CFTR has to be extracted from the ER membrane before degradation by the proteasome (4, 45), it is tempting to speculate that inhibition of ERAD steps before extraction, such as the E1–E3 ligase cascade, may indirectly facilitate protein escape from the ER.

Considering that corr-4a treatment had no effect on WT CFTR cell surface stability, these results complement a previous report demonstrating that low-temperature–rescued ΔF508 CFTR is still folded incorrectly at the cell surface and directed to the lysosome through a ubiquitin-dependent pathway, whereas the degradation of the WT protein from the cell surface is not ubiquitin dependent (47). Although the studies by Sharma and coworkers (47) show ubiquitin-dependent lysosomal degradation of ΔF508 CFTR, the studies by Gentzsch and coworkers (31) indicate that the cell surface stability of ΔF508 CFTR increased after proteasome inhibition. Therefore, whether ΔF508 CFTR degradation from the cell surface is mediated by the lysosome, the proteasome, or both remains an open question. Importantly, both proposed pathways seem to require ubiquitin, and our data clearly demonstrate that corr-4a interferes with ubiquitination.

Regarding the cell surface stability of ΔF508 CFTR, it has been established that rescued ΔF508 CFTR is rapidly cleared from the cell surface at 37°C (20, 29–31, 48). Results from Swiatecka-Urban (48) and coworkers suggest that the surface half-life of ΔF508 CFTR in CFBE41o- cells is 1 hour, which agrees with our previous studies indicating that the half-life is 2 hours (20). Chemical chaperones such as corr-4a seem to stabilize ΔF508 CFTR, but their mechanisms of actions are not clear. Our previous studies showed that the correctors, corr-4a and VRT-325, inhibit ΔF508 CFTR endocytosis and are specific for mutant CFTR (20). In our studies using human airway epithelial cells, we did not observe a corr-4a effect on WT CFTR levels or function. However, Pedemonte and coworkers (15) reported corr-4a effects in baby hamster kidney cells expressing WT CFTR. These results support the cell-specific differences in the processing of WT CFTR, as we described previously (49).

The results presented here also agree with our previous findings indicating that corr-4a had no effect on the cell surface stability or endocytosis of WT CFTR or the transferrin receptor, because cell surface clearance of these proteins does not require ubiquitination (20). We therefore hypothesize that corr-4a treatment may affect the cell surface clearance of all proteins that require ubiquitination. Considering that the optimal “corrector” for CF would be ΔF508 CFTR specific, our results also point to the importance of studies that investigate the complex mechanisms by which ΔF508 CFTR correctors work.

A recent study suggests that ΔF508 CFTR export requires a local folding environment that is sensitive to heat/stress-inducible factors found in some cell types, and these results suggest that low-temperature correction is necessary, but not sufficient, for ΔF508 export (50). In this intriguing study, the authors proposed that folding and rescue efficiency of ΔF508 CFTR depend on the cell type, and that the chaperone environment is a critical component for successful ΔF508 CFTR folding at reduced temperatures. Moreover, different chaperone activities or balance of activities may be responsible for the folding of ΔF508 CFTR at reduced temperature, and these may be different from WT. As it relates to our study, it is possible that E1–E3 inhibition also alters the chaperone environment, possibly through inducing ER stress and activating the unfolded protein response (24, 51).

Importantly, corr-4a enhanced the responsiveness of ΔF508 CFTR to cAMP after a 6-hour treatment. Although this result represents a significant functional improvement over untreated controls, cell surface biotinylation studies also indicated that, although ΔF508 CFTR was also present at the membrane for a longer time period (12 h), it did not respond to cAMP. This observation suggests that protein stability and functional integrity are distinct features of rescued ΔF508 CFTR. Therefore, regarding endpoint results for experimental therapies, FSK-stimulated channel activity is a better readout than the presence of protein at the cell surface. Our results point to a clearly unmet need for additional measures (e.g., potentiators) beyond stabilizing the protein, measures that functionally correct channel activity to activate all rescued channels at maximum capacity, and ameliorate CF symptoms.

Based on previous results, it is clear that, in human airway epithelial cells, ΔF508 CFTR channel function is compromised at 37°C, but not at 27°C (20). Furthermore, we have demonstrated that returning the cells to physiological conditions (37°C) after low-temperature rescue causes a rapid loss of functional activity (20). This observation clearly differentiates the act of stabilizing the protein at the cell surface, or, for that matter, promoting ER exit, from correcting channel function. Our studies also establish that understanding how low-temperature rescue works is critical for developing therapies designed to promote rescue, protein stability, and channel activity of ΔF508 CFTR. It may well be that identifying a single compound that corrects all ΔF508 CFTR defects may prove to be difficult. In addition to examining the mechanism and the effects of low-temperature rescue and corr-4a on ΔF508 CFTR, our studies also establish a protocol for the evaluation of newly identified chemical chaperones.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Robert Bridges (Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, IL), Dr. Melissa Ashlock (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics, Bethesda, MD), and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics for providing the pharmaceutical correctors.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants DK060065 (J.F.C.), HL076587 (Z.B.), and 1U54ES017218 and HL075540 (S.M.), and Cystic Fibrosis Foundation grant COLLAW08P0 (J.F.C.).

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0434OC on June 5, 2009

Conflict of Interest Statement: S.M. received grants for studies from Sepracor Inc. ($120,127) in 2007–2009 and from Talecris Biotherapeutics ($38,000) in 2007–2008, and has a U.S. Provisional Patent Application No. 61/052,414 “DPPC Formulations and Methods for Using” October 29, 2008. J.C. has a pending application to N30 on the role of GSNO on CFTR maturation. None of the other authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Sheppard DN, Welsh MJ. Structure and function of the CFTR chloride channel. Physiol Rev 1999;79:S23–S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Proesmans M, Vermeulen F, De Boeck K. What's new in cystic fibrosis? From treating symptoms to correction of the basic defect. Eur J Pediatr 2008;167:839–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng SH, Gregory RJ, Marshall J, Paul S, Souza DW, White GA, O'Riordan CR, Smith AE. Defective intracellular transport and processing of CFTR is the molecular basis of most cystic fibrosis. Cell 1990;63:827–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bebok Z, Mazzochi C, King S, Hong JS, Sorscher EJ. The mechanism underlying cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the proteasome includes sec61b and a cytosolic, deglycosylated intermediary. J Biol Chem 1998;273:29873–29878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward CL, Kopito RR. Intracellular turnover of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J Biol Chem 1994;269:25710–25718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward CL, Omura S, Kopito RR. Degradation of CFTR by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Cell 1995;83:121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gelman MS, Kannegaard ES, Kopito RR. A principal role for the proteasome in endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of misfolded intracellular cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. J Biol Chem 2002;277:11709–11714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalemans W, Barbry P, Champigny G, Jallat S, Dott K, Dreyer D, Crystal RG, Pavirani A, Lecocq J, Lazdunski M. Altered chloride ion channel kinetics associated with the ΔF508 cystic fibrosis mutation. Nature 1991;354:526–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bobadilla JL, Macek M Jr, Fine JP, Farrell PM. Cystic fibrosis: A worldwide analysis of CFTR mutations–correlation with incidence data and application to screening. Hum Mutat 2002;19:575–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denning GM, Anderson MP, Amara JF, Marshall J, Smith AE, Welsh MJ. Processing of mutant cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is temperature-sensitive. Nature 1992;358:761–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato S, Ward CL, Krouse ME, Wine JJ, Kopito RR. Glycerol reverses the misfolding phenotype of the most common cystic fibrosis mutation. J Biol Chem 1996;271:635–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egan ME, Pearson M, Weiner SA, Rajendran V, Rubin D, Glockner-Pagel J, Canny S, Du K, Lukacs GL, Caplan MJ. Curcumin, a major constituent of turmeric, corrects cystic fibrosis defects. Science 2004;304:600–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egan ME, Glockner-Pagel J, Ambrose C, Cahill PA, Pappoe L, Balamuth N, Cho E, Canny S, Wagner CA, Geibel J, et al. Calcium-pump inhibitors induce functional surface expression of delta F508-CFTR protein in cystic fibrosis epithelial cells. Nat Med 2002;8:485–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubenstein RC, Zeitlin PL. Sodium 4-phenylbutyrate downregulates hsc70: implications for intracellular trafficking of deltaF508-CFTR. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2000;278:C259–C267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedemonte N, Lukacs GL, Du K, Caci E, Zegarra-Moran O, Galietta LJ, Verkman AS. Small-molecule correctors of defective deltaF508-CFTR cellular processing identified by high-throughput screening. J Clin Invest 2005;115:2564–2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Goor F, Straley KS, Cao D, Gonzalez J, Hadida S, Hazlewood A, Joubran J, Knapp T, Makings LR, Miller M, et al. Rescue of deltaF508-CFTR trafficking and gating in human cystic fibrosis airway primary cultures by small molecules. Am J Physiol 2006;290:L1117–L1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlile GW, Robert R, Zhang D, Teske KA, Luo Y, Hanrahan JW, Thomas DY. Correctors of protein trafficking defects identified by a novel high-throughput screening assay. ChemBioChem 2007;8:1012–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Bartlett MC, Loo TW, Clarke DM. Specific rescue of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator processing mutants using pharmacological chaperones. Mol Pharmacol 2006;70:297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Loo TW, Bartlett MC, Clarke DM. Modulating the folding of p-glycoprotein and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator truncation mutants with pharmacological chaperones. Mol Pharmacol 2007;71:751–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varga K, Goldstein RF, Jurkuvenaite A, Chen L, Matalon S, Sorscher EJ, Bebok Z, Collawn JF. Enhanced cell-surface stability of rescued deltaF508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) by pharmacological chaperones. Biochem J 2008;410:555–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bebok Z, Collawn JF, Wakefield J, Parker W, Li Y, Varga K, Sorscher EJ, Clancy JP. Failure of camp agonists to activate rescued deltaF508 CFTR in CFBE41o- airway epithelial monolayers. J Physiol 2005;569:601–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goncz KK, Feeney L, Gruenert DC. Differential sensitivity of normal and cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells to epinephrine. Br J Pharmacol 1999;128:227–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jurkuvenaite A, Varga K, Nowotarski K, Kirk KL, Sorscher EJ, Li Y, Clancy JP, Bebok Z, Collawn JF. Mutations in the amino terminus of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator enhance endocytosis. J Biol Chem 2006;281:3329–3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rab A, Bartoszewski R, Jurkuvenaite A, Wakefield J, Collawn JF, Bebok Z. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the unfolded protein response regulate genomic cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator expression. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2007;292:C756–C766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunter JM, Lesort M, Johnson GV. Ubiquitin–proteasome system alterations in a striatal cell model of Huntington's disease. J Neurosci Res 2007;85:1774–1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen L, Patel RP, Teng X, Bosworth CA, Lancaster JR Jr, Matalon S. Mechanisms of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator activation by S-nitrosoglutathione. J Biol Chem 2006;281:9190–9199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma T, Thiagarajah JR, Yang H, Sonawane ND, Folli C, Galietta LJ, Verkman AS. Thiazolidinone CFTR inhibitor identified by high-throughput screening blocks cholera toxin–induced intestinal fluid secretion. J Clin Invest 2002;110:1651–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thiagarajah JR, Song Y, Haggie PM, Verkman AS. A small molecule CFTR inhibitor produces cystic fibrosis–like submucosal gland fluid secretions in normal airways. FASEB J 2004;18:875–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heda GD, Tanwani M, Marino C. The ΔF508 mutation shortens the biochemical half-life of plasma membrane CFTR in polarized epithelia cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2001;280:C166–C174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lukacs GL, Chang X-B, Bear C, Kartner N, Mohamed A, Riordan JR, Grinstein S. The ΔF508 mutation decreases the stability of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem 1993;268:21592–21598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gentzsch M, Chang XB, Cui L, Wu Y, Ozols VV, Choudhury A, Pagano RE, Riordan JR. Endocytic trafficking routes of wild type and deltaF508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Mol Biol Cell 2004;15:2684–2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bence NF, Sampat RM, Kopito RR. Impairment of the ubiquitin–proteasome system by protein aggregation. Science 2001;292:1552–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilon T, Chomsky O, Kulka RG. Degradation signals for ubiquitin system proteolysis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J 1998;17:2759–2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoyt MA, Coffino P. Ubiquitin-free routes into the proteasome. Cell Mol Life Sci 2004;61:1596–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Orlowski M, Wilk S. Ubiquitin-independent proteolytic functions of the proteasome. Arch Biochem Biophys 2003;415:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheaff RJ, Singer JD, Swanger J, Smitherman M, Roberts JM, Clurman BE. Proteasomal turnover of p21cip1 does not require p21cip1 ubiquitination. Mol Cell 2000;5:403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen X, Chi Y, Bloecher A, Aebersold R, Clurman BE, Roberts JM. N-acetylation and ubiquitin-independent proteasomal degradation of p21(cip1). Mol Cell 2004;16:839–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Touitou R, Richardson J, Bose S, Nakanishi M, Rivett J, Allday MJ. A degradation signal located in the C-terminus of p21waf1/cip1 is a binding site for the C8 alpha-subunit of the 20S proteasome. EMBO J 2001;20:2367–2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bao W, Thullberg M, Zhang H, Onischenko A, Stromblad S. Cell attachment to the extracellular matrix induces proteasomal degradation of p21(cip1) via cdc42/rac1 signaling. Mol Cell Biol 2002;22:4587–4597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kerem E. Pharmacologic therapy for stop mutations: how much CFTR activity is enough? Curr Opin Pulm Med 2004;10:547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramalho AS, Beck S, Meyer M, Penque D, Cutting GR, Amaral MD. Five percent of normal cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator mRNA ameliorates the severity of pulmonary disease in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2002;27:619–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heda GD, Marino CR. Surface expression of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator mutant deltaF508 is markedly upregulated by combination treatment with sodium butyrate and low temperature. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000;271:659–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharma M, Benharouga M, Hu W, Lukacs GL. Conformational and temperature-sensitive stability defects of the ΔF508 cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in post–endoplasmic reticulum compartments. J Biol Chem 2001;276:8942–8950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cui L, Aleksandrov L, Hou YX, Gentzsch M, Chen JH, Riordan JR, Aleksandrov AA. The role of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator phenylalanine 508 side chain in ion channel gating. J Physiol 2006;572:347–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiong X, Chong E, Skach WR. Evidence that endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator is linked to retrograde translocation from the ER membrane. J Biol Chem 1999;274:2616–2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vij N, Fang S, Zeitlin PL. Selective inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum–associated degradation rescues deltaF508–cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator and suppresses interleukin-8 levels: therapeutic implications. J Biol Chem 2006;281:17369–17378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharma M, Pampinella F, Nemes C, Benharouga M, So J, Du K, Bache KG, Papsin B, Zerangue N, Stenmark H, et al. Misfolding diverts CFTR from recycling to degradation: quality control at early endosomes. J Cell Biol 2004;164:923–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Swiatecka-Urban A, Brown A, Moreau-Marquis S, Renuka J, Coutermarsh B, Barnaby R, Karlson KH, Flotte TR, Fukuda M, Langford GM, et al. The short apical membrane half-life of rescued {delta}F508–cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) results from accelerated endocytosis of {delta}F508-CFTR in polarized human airway epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 2005;280:36762–36772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Varga K, Jurkuvenaite A, Wakefield J, Hong JS, Guimbellot JS, Venglarik CJ, Niraj A, Mazur M, Sorscher EJ, Collawn JF, et al. Efficient intracellular processing of the endogenous cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in epithelial cell lines. J Biol Chem 2004;279:22578–22584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang X, Koulov AV, Kellner WA, Riordan JR, Balch WE. Chemical and biological folding contribute to temperature-sensitive deltaF508 CFTR trafficking. Traffic 2008;9:1878–1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bartoszewski R, Rab A, Twitty G, Stevenson L, Fortenberry J, Piotrowski A, Dumanski JP, Bebok Z. The mechanism of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator transcriptional repression during the unfolded protein response. J Biol Chem 2008;283:12154–12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]