Abstract

This chapter presents novel microscopic methods to monitor cell biological processes of live or fixed cells without the use of any dye, stains, or other contrast agent. These methods are based on spectral techniques that detect inherent spectroscopic properties of biochemical constituents of cells, or parts thereof. Two different modalities have been developed for this task. One of them is infrared micro-spectroscopy, in which an average snapshot of a cell’s biochemical composition is collected at a spatial resolution of typically 25 mm. This technique, which is extremely sensitive and can collect such a snapshot in fractions of a second, is particularly suited for studying gross biochemical changes. The other technique, Raman microscopy (also known as Raman micro-spectroscopy), is ideally suited to study variations of cellular composition on the scale of subcellular organelles, since its spatial resolution is as good as that of fluorescence microscopy. Both techniques exhibit the fingerprint sensitivity of vibrational spectroscopy toward biochemical composition, and can be used to follow a variety of cellular processes.

I. Introduction

Over the past decade, novel micro-spectroscopic methods have opened new avenues for imaging individual cells, or fractions thereof, using a number of spectroscopic techniques. Confocal (one- and two-photon) fluorescence microscopy (see Chapter 5 of this volume) (O’Malley, 2008) is the best known of these techniques and has revealed amazing details on the complex structures found inside cells. Although many of the components inside a cell will exhibit auto-fluorescence, this effect is quite weak and nonspecific, and is generally not used in confocal fluorescence microscopy. Rather, labels or dye molecules [such as green fluorescent protein (GFP), small molecule dyes, or nanoparticles] are used to visualize organelles or receptor sites in cells by binding highly specific ligands to the labels. The resulting images exhibit spatial resolution determined by the diVraction limit: for fluorescence excitation in the mid-visible spectral range, the diVraction limit will be of the order of a few hundred nanometers.

In all imaging techniques that require a dye or a label, the question arises whether or not this dye interferes with the viability of the cells to be studied, and whether the diffusion of a receptor or a ligand is affected by the presence of the label, in particularly a bulky label such as a nanosphere. Therefore, the possibility of using label-free imaging methods is of interest to the scientific community. Among the label-free methods, newly developed techniques of vibrational microspectroscopic imaging (Diem et al., 2004) have gained acceptance in many fields such as nanoscience and semiconductor technology; however, their presence and acceptance in cell biology has been limited. The two most common techniques of vibrational micro-spectroscopy are infrared (IR) and Raman (RA) microspectroscopy (IR-MSP and RA-MSP). In both of these techniques, the inherent vibrational (IR or RA) spectra of the biochemical constituents of a cell are observed. Since every molecule exhibits its own distinct (“fingerprint”) spectrum (Diem, 1993), external labels are not required in these techniques.

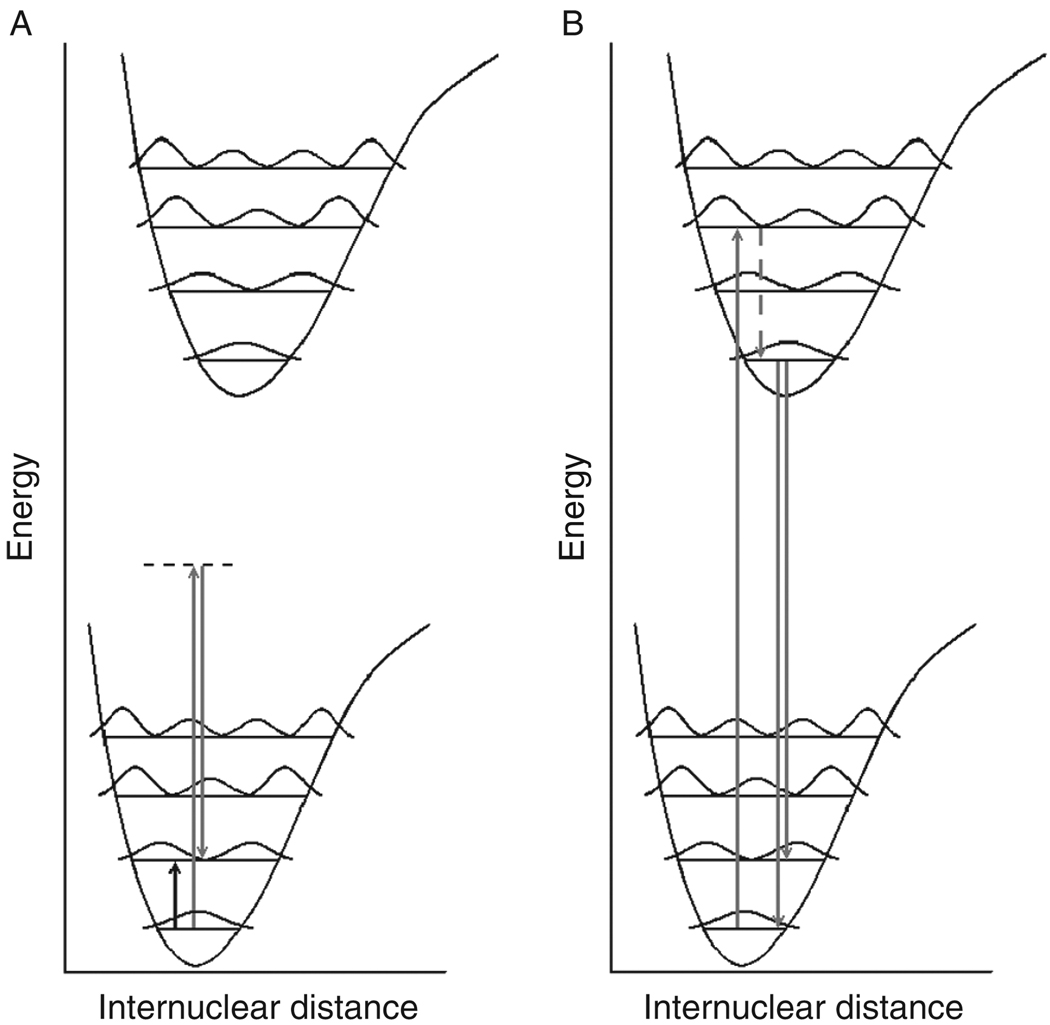

RA-MSP is an experiment, to be described in detail in Section II, that resembles fluorescence MSP in that monochromatic laser light is used to excite molecules in a sample. In fluorescence, the molecules are excited into a vibrationally excited state of the electronically excited state, which decays nonradiatively to the vibrational ground state of the electronically excited state (see Fig. 1). From there, a photon of reduced energy (red shifted) is emitted to a vibrationally excited state of the electronic ground state. In Raman spectroscopy, the incident laser light momentarily promotes the system into a “virtual” state, from which a red-shifted photon is emitted when the system decays into the vibrationally excited state of the electronic ground state. Thus, both fluorescence and Raman spectroscopy are vibronic effects (i.e., they involve both electronic and vibrational states and wave-functions); however, fluorescence probes more of the electronic states whereas Raman spectroscopy probes the vibrational states of a molecule. Since visible light is used for excitation in both cases, the spatial resolution (determined by the diffraction limit) is similar for both methods. However, Raman scattering is at least 6 orders of magnitude weaker than fluorescence, and consequently, could not be observed microscopically in cells until recently (Otto and Greve, 1998).

Fig. 1.

(A) Energy level diagram for infrared, Raman, and fluorescence transitions. In both panels A and B, the lower diagram represents the ground electronic state with associated vibrational energy levels and associated (squared) wavefunctions. The upper diagram represents the electronically excited state with associated vibrational energy levels and associated wavefunctions. (A) An IR transition (short black up-arrow) is a dipole-mediated transition from a lower to a higher energy vibrational state. A Raman transition occurs when a photon (gray up-arrow) with energy much higher than required for a vibrational transition, but insuffcient energy for an electronic transition, promotes the system into a virtual state (dashed line) from which a lower energy Raman photon is emitted (gray down-arrow). The emitted photon has lost the equivalent of the vibrational energy. (B). A fluorescence transition is initiated when a photon (gray up-arrow) promotes the system into an excited vibrational state of the electronically excited state. The vibrationally excited state depends on the overlap of the vibronic functions (Franck-Condon overlap). The system decays nonradiatively (dashed gray line) into the ground vibrational state of the electronically excited state. Red-shifted fluorescence (gray down-arrows) occurs from this state into various vibrationally excited states of the electronic ground state, depending on the maximal overlap of the wavefunctions involved.

IR-MSP probes the same vibrational states that are sampled by Raman spectroscopy by inducing a direct transition from the vibrational ground to the first vibrationally excited state (see Fig. 1). The photon energies required for this lie in the infrared spectral range (2.5–25 µm wavelength). IR spectroscopy is a qualitative and a quantitative spectral method commonly used in chemical research and in quality control. It is a much stronger effect than Raman spectroscopy, with extinction coefficients of the order of 1000 [mol/l cm]. (A strong UV–vis absorption may have extinction coefficients up to 105 [mol/l cm].)

IR-MSP has two distinct disadvantages. First, due to the longer wavelengths of the light, the diffraction limit is much larger than that in the visible range (see Section II.F). Second, many materials composed of highly polar bonds, such as glass or water, have very strong infrared absorptions, and are therefore opaque in the infrared spectral regions. Thus, instruments using all reflective optics, or using refractive lenses constructed from transparent materials such as NaCl, KBr, or CaF2 need to be designed. In spite of some experimental difficulties, both techniques are truly label-free in that the inherent vibrational signatures of the biochemical components of a cell are being observed.

The remainder of this chapter is organized as follows. First, instrumental methods and the mathematical procedures for data analysis will be presented. This discussion will be followed by IR-micro-spectral results collected for entire cells. These measurements monitor the composition averaged over the entire cell, and can detect variations of the composition as a gross observable. Very little spatial information of the compositional changes is available, due to the low spatial resolution of IR-MSP. On the other hand, the sensitivity to changes is very high, and IR-MSP can be used, for example, to determine the status of a cell during its progression through the cell cycle (Boydston-White et al., 2006). RA-MSP, in contrast, monitors variations in cellular composition at a spatial resolution comparable to the size of subcellular organization. Therefore, biochemical processes such as motion of a mitochondrion, or uptake of drug carriers, can be detected.

II. Methods

A. Infrared Spectroscopy

IR spectroscopy is a method most chemists, biologists, and biochemists are vaguely familiar with, since the dreaded undergraduate organic chemistry laboratory usually includes a few experiments involving identification of compounds by IR spectroscopy. It is a well-understood spectroscopic method in which the 3N–6 vibrational modes of a molecule consisting of N atoms are probed with IR light (2.5–25 µm wavelength). Each molecule, in principle, has its own distinct pattern of absorption peaks, which can be used as a fingerprint for molecular identification (Diem, 1993). Furthermore, the intensities of the absorption peaks are directly proportional to the concentration of components in a mixture; thus, IR spectroscopy serves both as a qualitative and a quantitative spectroscopic tool.

In typical undergraduate laboratory experiments, spectra from liquid samples (neat liquids or solutions) are collected from sample cells consisting of NaCl or KBr disks with spacers of appropriate thickness, which determine the sample path length. Solid samples are usually mixed with KBr and pressed into small pellets, or are ground up into a mull for data acquisition.

All commercial routine IR spectrometers employ interferometric techniques in which polychromatic IR radiation is intensity modulated by a Michelson-type interferometer (Diem, 1993). The resulting interferogram is Fourier-transformed to yield the familiar IR spectra displayed as percent transmission spectra, defined as 100 I(λ)/I0(λ), or absorption spectra, defined as –log[I(λ)/I0(λ)], plotted against the inverse of the wavelength of the light. This inverse wavelength is known as the wavenumber ν̄ of the light (measured in inverse cm), where a wavelength λ=2.5 µm corresponds to ν̄ = 4000 cm−1, and λ=25 µm corresponds to ν̄ = 400 cm−1.

B. Infrared Micro-Spectroscopy (Infrared Microscopy)

In IR-MSP), infrared spectra are acquired through a special microscope (Humecki, 1995; Messerschmidt and Harthcock, 1988). We discuss here the instrument used for most of the studies reported in this chapter. This instrument is manufactured by Perkin Elmer, Inc. (Shelton, CT) and consists of a Spectrum One Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectrometer bench coupled to a Spectrum Spotlight 300 IR microscope, henceforth referred to as the PE300. For single point (rather than imaging) application, a 100 µm × 100 µm HgCdTe (MCT) detector operating in photoconductive mode at liquid nitrogen temperature is used. The all-reflective objective provides an image magnification of 6x, and has a numerical aperture of 0.58. (Higher magnification could be achieved, but is irrelevant due to the long wavelength of the infrared light.) Visual image collection via a CCD camera is completely integrated with the microscope stage motion and IR spectra data acquisition. The visible images are collected under white light illumination, and are “quilted” together to give pictures of arbitrary size and aspect ratio. For single point measurements, individual cells are selected from the visually acquired sample image as seen on the screen. For each cell position on the sample substrate, the aperture is selected to straddle the cell, typically 30 µm × 3µm. Cell position and apertures are stored for each cell. Data acquisition of all stored positions proceeds automatically. The microscope and the optical bench are continuously purged with purified, dry air to reduce water vapor absorptions in the observed spectra. In addition, the sample area in the focal plane of the microscope is enclosed in a purged sample chamber.

The output of IR-MSP experiments consist of thousands of spectra of individual cells, along with the coordinates of each cell on the microscope slide. These coordinates are particularly important since they allow cells to be reregistered between the imaging and spectral data acquisition, and after the staining steps for high quality image acquisition.

C. Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy samples the same molecular vibrational states (Diem, 1993) as does IR spectroscopy discussed in Section II.A. However, Raman spectroscopy utilizes a scattering mechanism to excite the molecules into the vibrationally excited state, and visible wavelengths excitation is commonly used. Scattering phenomena are much less likely to occur than absorption processes; therefore, a laser which produces a large number of photons is needed for the excitation of Raman spectra. Despite the weak nature of the Raman effect, it offers several advantages over the more commonly used IR technique: since water has a very weak Raman scattering cross section (but a very strong IR absorption cross section), molecules and cells can be studied in aqueous environments. Furthermore, the use of visible excitation allows standard glass optics to be utilized, and the shorter wavelength light allows the detection of much smaller volume elements in RA-MSP than in IR-MSP. Aspects of the spatial resolution of both these techniques will be discussed later (Section II.F).

D. Raman Micro-Spectroscopy (Raman Microscopy)

In RA-MSP, Raman spectra are acquired from microscopic regions of a sample. For the studies reported here, RA-MSP Raman data were collected using a Confocal Raman Microscope, Model CRM 2000 (WITec, Inc., Ulm, Germany). Excitation (ca. 30 mW each at 488, 514.5, or 632.8 nm) is provided by an air-cooled Ar ion or HeNe laser (Melles Griot, Models 05-LHP-928 and 532, respectively). The exciting laser radiation is coupled into the Zeiss microscope through a single mode optical fiber, and reflected via a dichroic mirror through the microscope objective, which focuses the beam onto the sample. A Nikon Fluor (60×/1.00 NA, WD = 2.0 mm) water immersion or a Nikon Plan (100×/0.90 NA, WD = 0.26 mm) objective was used in the studies reported here (NA, numeric aperture; WD, working distance).

The sample is located on a piezo-electrically driven microscope scan stage with X–Y resolution of ca. 3 nm and a reproducibility of ±5 nm, and Z resolution of ca. 0.3 nm and ±2 nm repeatability. Raman backscattered radiation is collected for each data point through the same microscope objective, before being focused into a multimode optical fiber. The single mode input fiber (with a diameter of 50 µm) and the multimode output fiber (with a diameter of 50 µm as well) provide the optical apertures for the confocal measurement. The light emerging from the output optical fiber is dispersed by a 30 cm focal length monochromator, fitted with a back-illuminated deep-depletion, 1024 × 128 pixel CCD camera operating at –82 °C.

The output of a typical mapping RA-MSP experiment is a hyperspectral data set (also referred to as a hyperspectral data cube), consisting typically of between 10,000 and 50,000 individual Raman spectra, along with the coordinates from which each spectrum was collected. Analysis of such a hypercube will be discussed in Section II.G.

E. Typical Infrared and Raman Spectra of Cellular Constituents

Raman and infrared spectra of a molecule are complimentary in the sense that the same vibrational states are accessed in both techniques. However, infrared spectra are composed of broader bands than Raman spectra; thus, IR and RA spectra are sometimes difficult to compare. In order to increase the apparent spectral resolution, IR absorption spectra may be converted numerically to second derivative spectra, (d2 A/dν̄2), where A is the absorption spectrum. Second derivatives (2ndD) exhibit narrower and better-resolved peaks, and are more amenable to multivariate analysis (Section II.G). Bands strong in IR absorption often are weak in Raman scattering, and vice versa for reasons that are well understood.

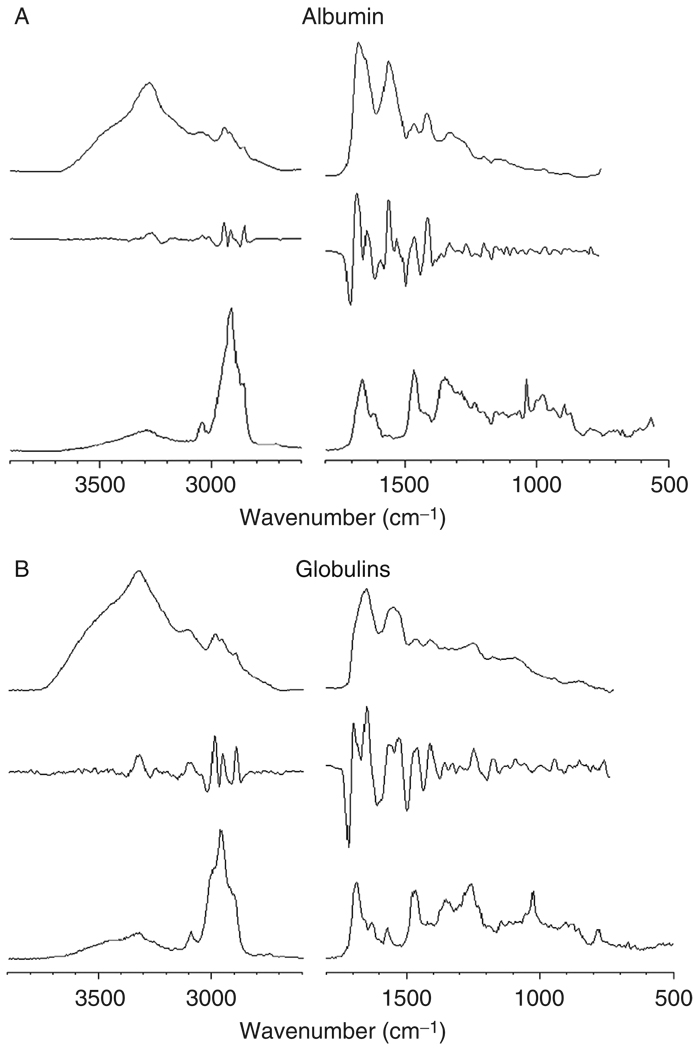

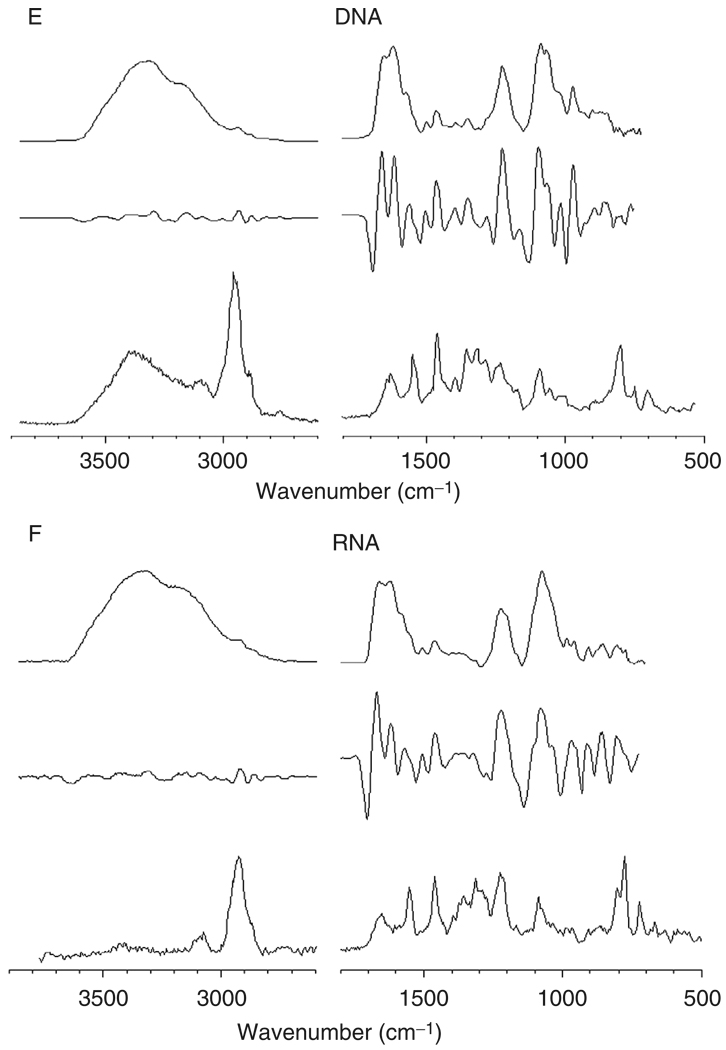

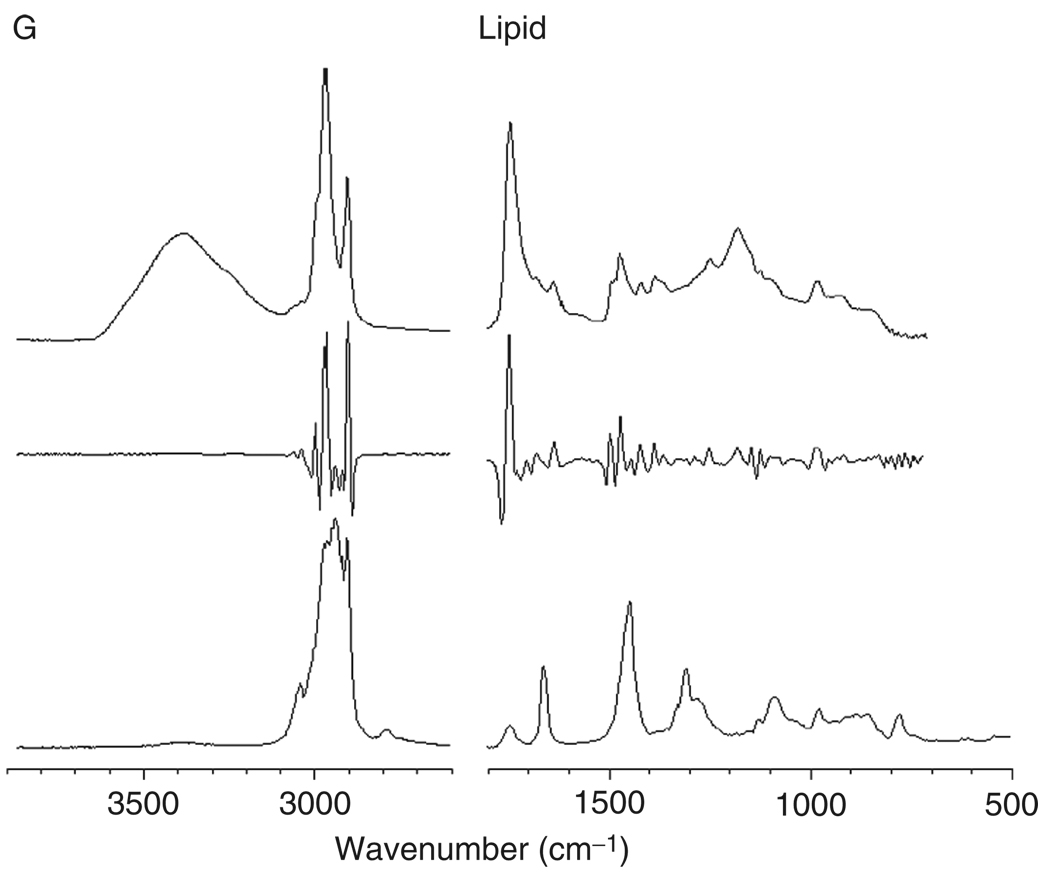

Figure 2, panels A–G, shows reference IR (top traces), 2ndD-IR (middle traces), and Raman (bottom traces) spectra of a number of cellular components. All 2ndD spectra were multiplied by –1 to present the spectra with positive peaks. Panel A shows spectra for a mostly α-helical protein, albumin; panel B shows mostly β-sheet proteins (a mixture of various globulins), and panel C shows a model for many structural proteins, collagen, which exists in a triple helical structure. All protein infrared spectra are dominated by the amide A (N–H stretching mode, ca. 3300 cm−1), the amide I (C=O stretching mode, ca. 1655 cm−1), the amide II (C–N stretching mode, ca. 1550 cm−1), and the amide III vibration (coupled N–H/Cα–H deformation mode). The complementary nature of RA and IR spectroscopy can be assessed by the fact that the amide II band is weak in the Raman spectra, but is strong in IR spectra. Similarly, the amide III mode is weak in IR, but strong in Raman spectra. Collagen exhibits a very characteristic spectrum in the amide III region, with a triplet of peaks at 1202, 1282, and 1336 cm−1 and another weak triplet between 1000 and 1100 cm−1.

Fig. 2.

Spectra of cellular components. In each panel, the top trace represents the infrared absorption spectrum (in arbitrary absorbance units), the middle trace represents the negative second derivative of the infrared spectrum, and the bottom trace represents the Raman spectra in arbitrary scattered intensity units. All spectra were acquired microscopically from thin films. (Panel A) Albumin (α-helical); (panel B) globulin mixture (β-sheet); (panel C) collagen (triple helical); (panel D) glycogen; (panel E) DNA; (panel F) RNA; and (panel G) lipid.

Amino acid side chains play minor roles in the spectra of proteins, and some of their spectral features are summarized in Table I. The strength of vibrational methods lies in their ability to distinguish protein secondary structures. A comparison of the 2ndD spectra of albumin and globulin shows distinct spectral differences in the amide I manifold of peaks: the helical protein exhibits a sharp peak at 1655 cm−1, whereas the sheet protein exhibits two peaks at ca. 1635 and 1690 cm−1. This comparison also demonstrates the usefulness of second derivative spectroscopy: the corresponding changes are harder to discern in the original IR spectra than in the 2ndD spectra.

Table I.

Vibrational Frequencies (in cm−1) and Assignments of Peaks Found in the Spectra of Cells

| 3300 | Amide A (N–H stretching mode, peptide linkage) |

| 2950 | CH3 antisymmetric stretching mode |

| 2920 | CH2 antisymmetric stretching mode |

| 2880 | CH3 symmetric stretching mode |

| 2850 | CH2 symmetric stretching mode |

| 1735 | >C=O stretching mode, ester linkage |

| 1690–1620 | Amide I (>C=O stretching mode, peptide linkage) |

| 1570–1530 | Amide II (C–N stretching mode, peptide linkage) |

| 1468–1455 | CH3/CH2 antisymmetric bending mode |

| 1397 | –COO– symmetric stretching |

| 1379 | CH3 symmetric bending mode |

| 1340–1240 | Amide III (coupled N–H/C–H deformations) |

| 1237 | O–P=O antisymmetric stretching mode |

| 1150 | C–O stretching, C–O–H bending modes (carbohydrates, mucin) |

| 1083 | O–P=O symmetric stretching mode |

| 1063 | –CO–O–C symmetric stretching mode |

| 1050 | C–O stretching mode (carbohydrates, mucin) |

| 1004 | Phenylalanine ring breathing mode |

| 968 | C–O–P phosphodiester residue (DNA) |

The vibrational spectra of glycogen are shown in Fig. 2, panel D, as prototypical spectra of a carbohydrate. Glycogen spectral contributions are found prominently in the spectra of some epithelial cell types, and in tissues such as liver. Glycogen has a similar spectrum as its monomeric analogue glucose; however, glucose is metabolized rapidly and is normally not observed in cells or tissues. The major spectral bands of glycogen are the coupled C–O stretching and C–O–H deformation modes observed as a triplet of peaks at ca. 1025, 1080, and 1152 cm−1.

Panels E and F show spectra of DNA and RNA, respectively. These molecules exhibit typical aliphatic and aromatic C–H stretching bands between 2850 and 3050 cm−1, which are particularly pronounced in the Raman spectra, and C=N, C=C, and C=O double bond stretching frequencies of the planar bases between 1600 and 1700 cm–1 . These spectra show distinct phosphate peaks at ca. 1235 and 1085 cm–1. In the context of this discussion, the biochemical nomenclature is used, where “phosphate” refers to the phosphodiester linkage:

The central phosphorus atom is tetrahedrally surrounded by four oxygen atoms and bears a negative charge that is countered in DNA by Na+ ions. The central group also exhibits multiple bond character. The terms “symmetric” and “antisymmetric” phosphate stretching vibration refer to the vibrations of the central group, and are normal modes observed at ca. 1085 and 1235 cm−1, respectively. These vibrations are conserved between many species containing this group, that is, DNA, RNA, and phospholipids. The vibrations of the –O–P–O–moiety are referred to as the phosphodiester vibrations, which are less intense in the infrared. The vibrational modes of these molecules are summarized in Table I as well.

In phospholipids, the same phosphate group vibrations are found (see Fig. 2, panel G). In addition, these molecules exhibit strong C–H stretching vibrations, due to the long fatty acid side groups. The –CH2– vibrations of these groups convey information on the local arrangement of the fatty acid chains. In addition, phospholipids exhibit a distinct vibration at ca. 1740 cm−1 due to the ester linkage.

F. Diffraction Limit and Spatial Resolution

RA-MSP data are acquired confocally; that is, using a two-pinhole arrangement that restricts the lateral size and depth of the sample volume element (voxel). In confocal microscopy, the lateral spatial resolution δlat of the acquired sampling area is determined by the diffraction limit, and is given by (Otto and Greve, 1998):

| (1) |

Depending on the laser wavelength (488, 514.5, or 632.8 nm for the RA-MSP unit described above) and objective used, a lateral resolution between ca. 300 and 435 nm can be achieved. The axial (depth) resolution is given by:

| (2) |

resulting in a theoretical depth resolution for the water (n = 1.33) immersion objective (NA = 1) between ca. 1300 and 1700 nm, for 488 and 632.8 nm excitation, respectively.

The IR-MSP data reported here are not acquired confocally, although the microscope aperture (typically 30 µm) and the detector size somewhat restrict the confocal depth which is sampled. However, this depth is much larger than the sample thickness (<8 µm) that can be used before the absorption bands become too strong to be observed reliably. The lateral resolution predicted by the diffraction limit would be ∼10 µm at a wavelength of 10 µm if the measurement was carried out confocally, but with an aperture of 10 µm, the light throughput would be compromised for the PE300 instrument. However, confocal IR-MSP measurements have been reported using synchrotron-based IR-MSP (Carr, 2001).

G. Multivariate Methods of Data Analysis

All multivariate methods of data analysis are based on the principle that there exist small, but reproducible changes in the spectra that can be associated with the variations in sample properties that are investigated. For cells during the cell cycle, for example, very slight shifts in the position of the amide I and II bands occur that are due to different protein compositions of cells at the different stages of the cell cycle. Although these changes may be masked by confounding factors, and may be hidden under uncorrelated (random) variations due to a large variance of the spectral data, multivariate methods will detect these changes and provide a correlation with the stage in the cell cycle. For these methods to work properly, large data sets are required, and the analysis proceeds by calculation of a correlation matrix that expresses both random and correlated changes in the spectra.

1. Principal Component Analysis

The principal component analysis (PCA) is an ideal method to determine whether the variance in the spectral pattern of individual cells is correlated, or is due to random fluctuations (Adams, 2004). In PCA, an intensity point at a given wavenumber is correlated to other intensity point, and this correlation is summed over all spectra. A frequency correlation (covariance) matrix is obtained that consists of M2 entries, where M is the number of intensity points in each spectrum. Subsequently, new spectra, known as the “principal components” (PCs), are computed to contain the maximum variance of the data set. Typically, the first few (5–8) PCs contain all the spectral information; higher PCs are mostly due to noise. Thus, each spectrum of the original data set can be expressed as a linear combination of a few PCs, with the expansion coeffcients α expressing how much each PC contributes to a spectrum. Similar spectra will exhibit a set of similar values of α; thus, a plot of the contributions αi for two PCs will yield a scatter plot, in which each dot represents a spectrum. Such a plot is known as a “scores plot.” If these dots are found in distinctive clusters, the spectra in each cluster are closely related (similar) and distinct from spectra in a diVerent cluster. If the dots in a scores plot are uniformly distributed around the origin, the variance in the data set is not correlated to any systematic changes.

2. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis

We use hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) to construct spectral images from hyperspectral data cubes (see Section II.D) without human intervention. These spectral images are based solely on the similarity of the spectra in a hyperspectral data set. A detailed description of HCA has been published (Diem et al., 2004; Lasch et al., 2004; Wood et al., 2004). For HCA, the pair-wise similarity coeffcients of all spectra in a data set are collected as a matrix of correlation coeffcients C, which contains N2 entries, where N is the total number of spectra in a data set. Each correlation coeffcient between two spectra can range from 1.0 for identical spectra to 0.0 for totally different spectra. The correlation matrix is then searched for the most similar spectra, which are merged into a new object employing an algorithm introduced by Ward (1963). The correlation matrix is recalculated and the merging process repeated until all spectra are combined into a small number of clusters. Each cluster is assigned a color, and these colors are displayed at the coordinates at which the spectra were collected creating a pseudo-color map based on the spectral similarity. Mean cluster spectra, obtained by averaging all spectra in a cluster, provide insight into the spectral differences between clusters, and offer a measure of the compositional variations of the cellular regions associated with the clusters. The mean cluster spectra exhibit vastly improved signal-to-noise ratios over individual spectra. HCA, using Ward’s algorithm as a merging method, was found to produce the best clusters as judged by the homogeneity of the spectra in each cluster (Helm et al., 1991).

H. Sample Preparation

Because of the strong IR absorption of water, samples for IR-MSP are best prepared by drying the cells on a suitable sample substrate. Cells may be grown in culture directly on a substrate, or may be centrifuged or sedimented onto the substrate, and subsequently (formalin) fixed and dried. Suitable substrates are water-insoluble salt plates (CaF2, BaF2, and ZnSe) or Ag-coated glass slides (“low-e” slides) used in reflectance measurements. It is difficult, yet possible, to observed cells in an aqueous environment (see Section III.B.5).

RA-MSP data can be acquired from aqueous environments due to the low Raman scattering cross section of water. To this end, cells centrifuged or otherwise attached to nonfluorescent, insoluble substrates (quartz or CaF2) are immersed in water, buffer, or cell culture medium and studied through a water immersion objective. The aqueous environment also offers the advantage of dissipating the optical power of the laser beam (∼5 × 106 W/cm2 power density), thus preventing cell damage.

III. Results and Discussion

A. General Comments: Pros and Cons of IR-MSP and RA-MSP

IR-MSP and RA-MSP both monitor the total chemical composition contained in the sampling volume. Since a cell is composed of thousands of structural and metabolic proteins, nucleic acids, many different phospholipids, carbohydrates, and small molecules that may be involved in signaling pathways, the observed spectrum of a cell is a superposition of the spectra of thousands of cell constituents. The interior of a cell is not a homogeneous solution of the above-mentioned components, but rather a highly compartmentalized and organized structure. Only the largest of these organizations can be detected in IR-MSP (i.e., nucleus and cytoplasm), whereas organelles as small as 1 µm in diameter can be observed in RA-MSP. This is, of course, due to the diffraction limit, which is proportional to the wavelength and which determines the smallest object that can be resolved in microscopy. However, the average measurement performed in IR-MSP affords much higher spectral quality, as determined by the signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio of the data. Thus, small spectral shoulders, peak shifts, and intensity variations can be detected. In addition, IR-MSP measurements averaged over an entire cell can be carried out in a few seconds, whereas RA-MSP data acquisition will take 100 times longer, and usually samples only a small part of the cell. Thus, IR-MSP provides a snapshot over the biochemical composition integrated for an individual cell, whereas RA-MSP provides a spatially resolved image of cellular compartments and structures, albeit at lower sensitivity and signal quality.

B. IR Results of Individual Cells

1. Monitoring Overall Cell Composition

We begin the discussion of observed cellular IR-MSP by presenting results collected from cultured human fibroblast cells (ATCC cell line CRL 7553). Figure 3 shows typical IR-MSP spectra for the nucleus and cytoplasm of such cells. These spectra represent average spectra from the nuclei of 15 individual cells (trace 1) and the cytoplasm of the same cells (trace 4). The spectra shown are typical for actively growing cultured cells, and are dominated by the protein spectra shown in Fig. 2A and B. In addition, peaks associated with phospholipids and nucleic acids can be observed. In order to identify the biochemical components in a cell, the cells were treated on the spectral substrate with ethanol, to partially dissolve phospholipids, and with RNase to remove nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA.

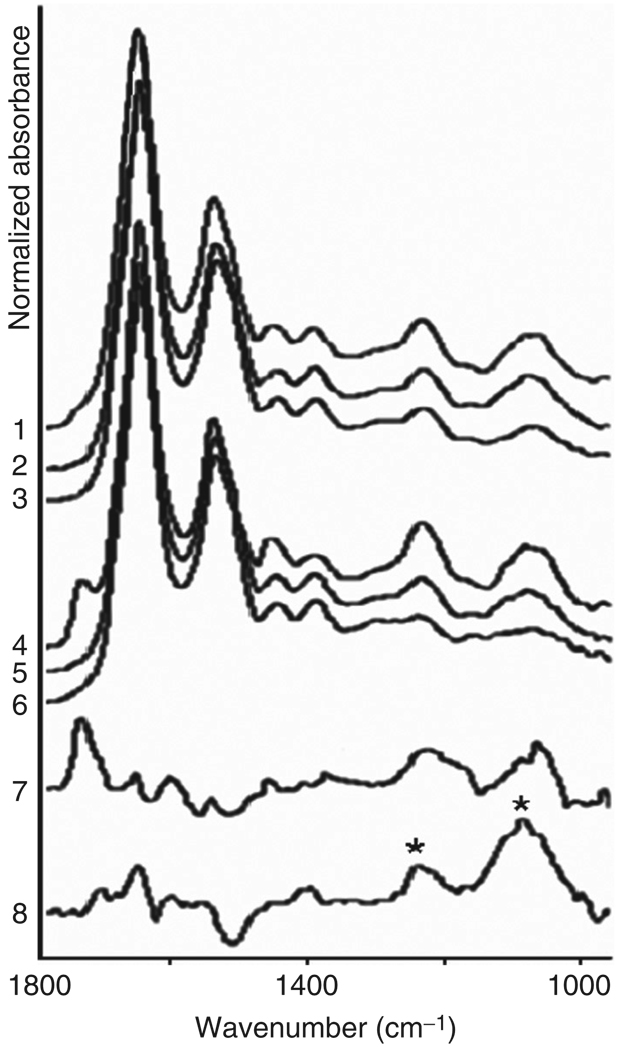

Fig. 3.

IR-MSP spectra of cultured human fibroblast cells. Traces 1–6 represent average spectra from 15 individual cells, and were normalized for equal amplitudes at the amide I band (ca. 1650 cm−1). Traces 1 and 4 are from the nuclei and cytoplasm of dried cells, respectively. Traces 2 and 5 are from the nuclei and cytoplasm, respectively, of cells after ethanol treatment to remove phospholipids. Traces 3 and 6 are from the nuclei and cytoplasm, respectively, after RNase digestion. Trace 7 shows the difference spectrum before and after ethanol treatment (trace 4–trace 5), amplified four times. Trace 8 (trace 2–trace 3) shows the effect of RNase digestion in the nucleus. The difference spectrum closely resembles that of pure RNA (see Fig. 2F).

After each of the sample treatments (ethanol, RNase), the same 15 cells were reinvestigated. In addition to improving the S/N of the observed spectra, this averaging minimizes cell-to-cell variations in these data. The spectra shown in Fig. 3 were normalized for equal amplitudes at the amide I band (ca. 1650 cm−1). In Fig. 3, traces 1, 2, and 3 represent spectra from nuclear, and traces 4, 5, and 6 from cytoplasmic regions, respectively. Traces 1 and 4 were collected from the untreated cells, traces 2 and 5 after ethanol extraction, and traces 3 and 6 after RNase digestion. These spectra reveal an enormous amount of information on the contributions to the observed spectra of the classes of biomolecules found in a cell. The spectra of nuclei and the cytoplasm differ mostly in the lipid band (at 1738 cm−1 due to C=Oester, see traces 1 and 4).

Ethanol treatment was carried out by exposing cells on a substrate for 5 min to 96% ethanol (Fisher Scientific) to eliminate most phospholipids, the removal of which manifests itself by the disappearance of the C=Oester peak at 1738 cm−1 (Fig. 3, traces 2 and 5). The effect of ethanol treatment may also cause dehydration of proteins and nucleic acids, aggregation of proteins, and removal of phospholipids. However, the spectra of the treated cells showed minimal spectral changes aside from those expected due to the removal of the phospholipids.

After ethanol treatment, the intensity profiles of the symmetric and antisymmetric phosphate stretching bands at 1085 and 1235 cm−1, respectively, display small differences between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, as shown in Fig. 3. These indicate that the concentration of the remaining –– groups from DNA and RNA is higher in the nuclei than in the cytosol. A difference spectrum for the cytosol, before and after ethanol treatment (trace 4–trace 5), is shown in trace 7. This trace, amplified four times, represents the spectra of phospholipids reasonably well, and we may conclude that the spectral components removed from the cells were, indeed, phospholipids. The observed difference spectra were larger for the cytosol than for the nucleus.

RNase digestion of cells attached to substrates was accomplished by incubating them twice with a solution of RNase A (1 mg/ml, type III, from bakers yeast, Sigma-Aldrich Co.) for 15 min at 37 °C (Chiriboga et al., 2000; Lasch et al., 2002). Subsequently, the slides were rinsed twice with distilled water and allowed to air-dry. Normally, RNase treatment is preceded by washing with detergents to render the cell’s interior accessible to the enzyme. Since the ethanol treatment removed most of the cell membrane, we found that RNase digestion works without the detergent treatment, reducing the cytoplasmic RNA concentration significantly.

Figure 3, traces 3 and 6, depicts the effect of RNase digestion. This step removes cytoplasmic and nuclear RNA, resulting in nearly complete removal of the RNA contribution to the spectra of cytosol. This demonstrates that the cytoplasmic RNA is detectable by IR-MSP. The cytoplasmic RNA is most likely in the form of ribosomes involved in protein synthesis. Nucleic acid features persist in the nuclear region, due to DNA and possibly undigested RNA in the nucleus. Further digestion with DNA removed nearly all nucleic acid contributions (data not shown, see Lasch et al., 2002). The difference spectrum shown in trace 8 shows the effect of RNase digestion in the nucleus. The difference spectrum is that of pure RNA (Diem et al., 1999), with the distinct structure of the 1080 cm−1 peak and an intensity ratio of nearly 2:1 for the 1080/1235 cm−1 vibrations (see Fig. 2F, bands marked by asterisks). The remaining spectra of the cytoplasm (trace 6 in panels A and B) are dominated by protein features, and resemble the spectra shown in Fig. 2A. The data reported here indicate that most of the observed phosphate signals in an active cell are due to RNA and phospholipids, which are found in high concentrations in the cytoplasm of active cells. One of the most fascinating aspects of the spatially resolved data is the detection of the sheer abundance of the phospholipids in the cytoplasm outside the nucleus. On the basis of the known thickness of the bilayer membrane surrounding a cell, an argument can be made that it is impossible to observe its contribution to the spectrum of a cell. Thus, we suggest that the phospholipid signal at 1738 cm−1 results mostly from membranes of subcellular organelles such as the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus that contain large amounts of phospholipids. Recent confocal Raman data have confirmed this observation (see Section III.C). It is unlikely that the outer membrane can be observed in transmission micro-spectroscopy, since its thickness is insufficient for a detectable IR signal.

Another cellular compound that may be removed relatively easily is glycogen. Several tissue types, such as liver tissue, and many squamous cells (e.g., cells from the human ecto-cervix, esophagus, and distal urethra) accumulate glycogen in significant amounts. Since the signals of glycogen mask the low wavenumber region of cells and tissues, it is advantageous to remove glycogen by digestion with α-amylase. When squamous cells from the distal end of the urethra are treated with α-amylase following standard histological procedures, one finds that the glycogen signal is completely removed (see Fig. 4, glycogen region marked by an asterisk). However, the overall protein intensity is also reduced by nearly an order of magnitude. The reason for the reduction of the entire cell absorption intensity is not understood at this point. Possibly, the amylase digestion solubilizes glycoproteins on the cell surface, which are subsequently removed in the washing steps.

Fig. 4.

Images and spectra of human superficial squamous cells before (A and C) and after (B and D) digestion of glycogen by α-amylase. Note the disappearance of the three glycogen peaks between 1000 and 1200 cm−1, and the concomitant decrease in overall spectral amplitude.

2. Infrared Spectral Heterogeneity of Exfoliated Cells and Distinction of Cell Types

We have used oral mucosa (buccal) cells as one of the most easily obtainable exfoliated cell types from volunteer donors. These cells were exfoliated by gently swiping the oral cavity with sterile polyester swabs, and washing the obtained cells repeatedly in buffered saline solution (BSS). In this section, spectra collected from entire individual cells are used to introduce the possibility of using infrared microspectral results to distinguish cell types and determine their state of health. We found that the spectra of harvested, mature human buccal cells show large heterogeneity, which is now well understood. This was discussed in detail before (Romeo et al., 2006). Similarly, the averaged spectra from several donors (data not shown, see Romeo, 2006) appeared quite diVerent, and it was not clear at the onset of this work whether this heterogeneity would prevent application of IR-MSP as a diagnostic method.

Despite the apparent diVerences in the spectra shown in Fig. 5, we were able to interpret them via appropriate preprocessing and multivariate statistical methods. The preprocessing applied uniformly to all spectra includes computation of second derivatives of the absorption spectra with respect to wavenumber and subsequently normalization of the derivative spectra. This methodology was pioneered by the Naumann group at the Robert Koch Institut in Berlin, Germany, for the analysis of spectral data of prokaryotic cell colonies (Naumann et al., 1988). A PCA scores plot of these data, see Romeo (2006), collected from over 400 human cells, reveals a reasonably uniform distribution of the spectra, and indicates that there are only small variations between the cells from diVerent donors.

Fig. 5.

(Panel A) Natural variance of IR spectra of exfoliated human oral mucosa (buccal) cells collected from one donor.

Furthermore, the diVerences found between buccal cells are smaller than those observed when another cell type is added for comparison, for example, canine cervical cells. These cells were selected for a number of reasons. Morphologically, human oral mucosa cells and canine cervical cells are nearly identical, and both represent glycogen-free squamous epithelial cells. (Human cervical cells exhibit strong glycogen signals; therefore, their distinction from human buccal cells is trivial.) Furthermore, in terms of their biochemical composition, which ultimately determines the observed IR spectra, human buccal and canine cervical cells are expected to be very similar. Canine cervical cells can be obtained by gently scraping the excised cervix from spayed dogs with a miniature dental brush, and vortexing the cells from the brushes in BSS.

Thus, we thought it an important test of the spectral methodology to determine whether or not these cells could be distinguished. In total, seven sets of human oral mucosa cells (comprising 427 spectra), and five sets from animals (560 spectra) were combined into one data set and analyzed via PCA. The scores plots (PC2 vs PC3) of uniformly preprocessed data are shown in Fig. 6A, and the PC3 versus PC4 plot in Fig. 6B. The separation between canine cervical and human buccal cells is excellent in both plots.

Fig. 6.

(A) Scores plot (PC2 vs PC3) and (B) PC3 versus PC4 of human buccal and canine cervical data sets.

When the spectra of cells from dogs in estrus were incorporated into the PCA, they were found to fall exactly within the range of the human buccal cells, and were well separated from the spectra of cells of non-estrus dogs. The explanation of this spectral diVerentiation may be found in the level of maturity of the cells examined (Romeo, 2006). The human buccal cells, exfoliated from the oral mucosa, are mature squamous epithelial cells. These cells are typically between 50 and 60 µm on edge. For non-estrus dogs, the cervical cells are not completely mature, and are generally classified as intermediate squamous cells (Holst, 1985). These cells are smaller, ∼25–35 µm on edge. During estrous, hormonal changes cause maturation of the canine cervical cells from intermediate to superficial cells. In this process, the cells enlarge to about the same size as mature human cervical or human buccal cells. At the same time, the nucleus decreases in size and may even become pyknotic for completely mature cells. This fact is well known in cytology, and is used to differentiate between intermediate (immature) and superficial (mature) human cervical cells.

Thus, we have used the nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio (N/C) of cells to explain the differentiation between human buccal and cervical cells from estrous dogs on one hand, and immature cervical cells on the other. Since the nucleus contributes much more strongly to the overall spectrum of the cell than the cytoplasm (Romeo et al., 2006), variations in the N/C ratio will greatly affect the observed spectra. Thus, we suggest that the discrimination between immature and mature cells is a direct consequence of the N/C ratio of these cells, as demonstrated for the (intermediate) canine cervical cells on one hand, and mature human buccal cells and mature canine cervical cells on the other.

3. Cell Cycle Dependence of Cellular Spectra

In order to explain the spectral heterogeneity of samples of cultured as well as exfoliated cells, we embarked on a study to investigate whether the stage in the cell’s division cycle might influence their spectral characteristics. To this end, HeLa cells grown in culture were synchronized using “mitotic shake-off’ and stained to identify the stage of the cell cycle.

Mitotic shake-off was carried out by first removing poorly adherent and dead cells by shaking the cell flasks on a laboratory vortex mixer and subsequently replacing the supernatant with 15 ml of fresh Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, ATCC), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, ATCC). After incubation for 1 h, the flasks were once again shaken on the vortex mixer to remove spherical cells presumed to be undergoing mitosis. The medium was immediately centrifuged for 6 min at 80xg to collect the cells, which were resuspended in warm DMEM culture medium, seeded onto slides, and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The appearance of two daughter cells was observed for most of the original cells.

At 1-h intervals, slides were removed from the incubator. All cells on a given slide should be in approximately the same stage of the cell cycle (or at the same “biological age”), since they all went through mitosis at the same time. To further determine the cells’ biological age, we used common biochemical markers which indicate the presence of cell cycle-specific proteins (cyclin E for G1 phase, cyclin B1 for G2 phase) and 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation (Aten et al., 1992) for S phase. BrdU incorporation needs to be carried out before infrared data acquisition, whereas the cyclin antibody stains could be added to the cells afterwards.

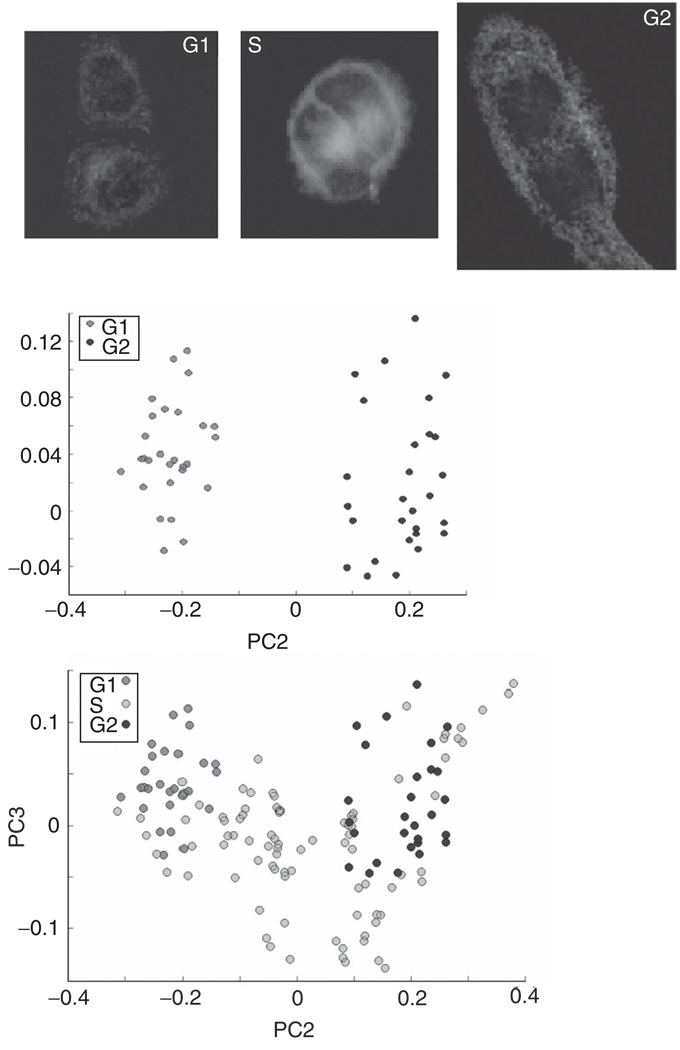

Following data collection, cells were subjected to immunohistochemical staining to determine their biochemical age in the cell cycle. Details of all procedures may be found in the literature (Boydston-White et al., 2005). Figure 7A shows the typical staining pattern for each of the three populations (G1, S, and G2) of cells within the division cycle. Positive red staining for cyclin E indicates that the cells were in the G1 phase (Koff et al., 1991) at the time of fixation. Since the thymidine analog BrdU is integrated into nuclear DNA only during DNA synthesis during the S phase, the green fluorescence staining for BrdU indicates that the cell was actively synthesizing DNA. Finally, a group of cells exhibited only positive yellow fluorescence staining for cyclin B1, and was assigned to the G2 phase.

Fig. 7.

(Panel A) Immunohistochemical staining to confirm the biological age of HeLa cells which were partially synchronized by mitotic shake-oV. In addition to the immunohistochemical stains described in the text, the cells were DAPI-stained (blue) to visualize the nuclear DNA. (Panel B) PCA plot of cells which were determined to be in G1 and G2 stages via staining and synchronization procedures. (Panel C) PCA plot of cells which were determined to be in G1, S, and G2 stages via staining and synchronization procedures.

In Fig. 7B, scores plots of cellular populations are presented. The separation between G1 and G2 stages is very good, indicating that there are systematic variations in the protein spectra between G1 and G2 stages. This result is not too surprising, considering that in G1 the proteins for DNA replication are synthesized, whereas in G2 proteins for mitosis are synthesized.

However, the S-phase spectra do not form a distinct cluster, but span the entire PC3/PC2 space, with much larger variance than the G1/G2 cells (Fig. 7C). Thus, we conclude that S-phase spectra cannot easily be separated from G1- and G2-phase spectra. Spectrally, some S-phase cells appear very similar to G1 cells, while others appear similar to G2-phase cells. Still other S-phase cells have quite different spectra from both G1- and G2-phase cells. The reasons for the spectral heterogeneity in the S phase are not clear at this point. The discrimination between G1 and G2 stages is based mostly on changes of the amide I and II bands. We observe a shift of 10 cm−1 in the amide I peak position, accompanied by a shift in an amide I shoulder, and a shift of the amide II peak, as the cells progress through the G1, S, and G2 phases, indicative of changes in protein structures (Boydston-White et al., 2005).

4. Normal and Abnormal Cells

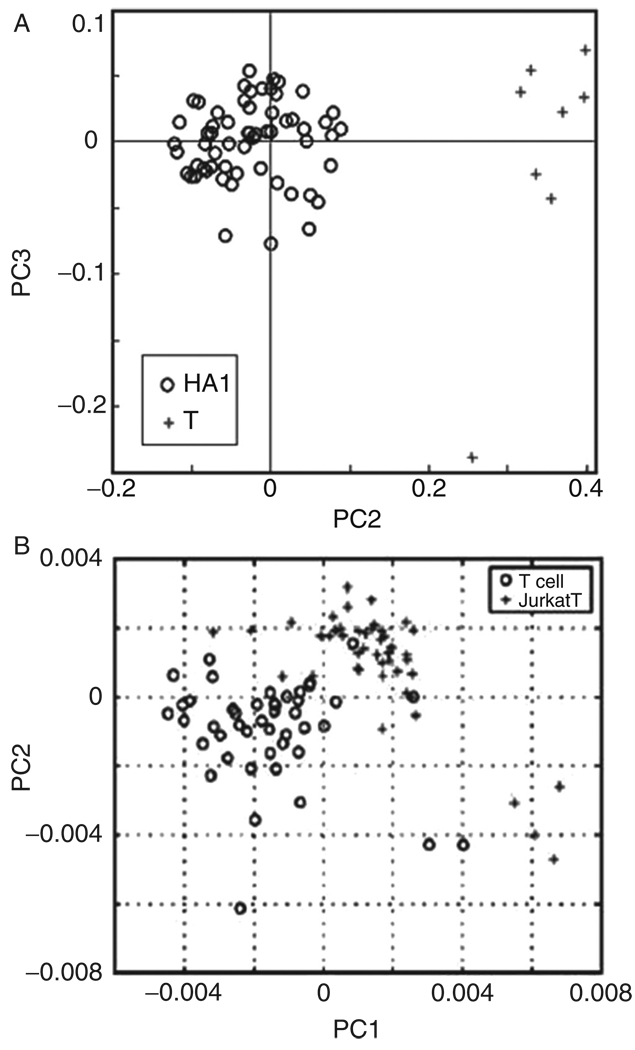

Although spectral differences between cancerous and normal tissues have been demonstrated by a number of research groups, and for a variety of tissue types, reliable results on the single cell level have been less frequent. This is, at least partially, due to the fact that large-scale single cell spectroscopy was not practical until about 2003, when more sophisticated and sensitive IR-MSP instruments became available. We have detailed spectral differences at the single cell level for cervical dysplasia, and more recently, between normal and malignant lymphocytes (see Fig. 8). Very similar results have been reported by Chan et al. (2006) using RA-MSP, followed by PCA analysis. A large-scale study of normal and cancerous urothelial cells is presently being carried out in the authors’ laboratory.

Fig. 8.

(Panel A) PCA scores plot for infrared spectra of normal human T lymphocytes (crosses) and HA-1 T-cell lymphoma cells (circles). (Panel B) PCA scores plot for Raman spectral differentiation of normal human T-cells (circles) and Jurkat cells (crosses).

5. Infrared Spectral Studies of Live Cells

Here, we wish to discuss briefly the observation of IR-MSP of individual human cervical cancer (HeLa) cells suspended in buffer or cell culture medium. IR spectroscopy of cells in an aqueous environment is difficult because of the very strong water vibrations that interfere with the protein amide I, II, and A vibrations. The strong absorption of water also necessitates the use of very short sample pathlength, typically between 8 and 10 mm. Such a short pathlength is suitable if cells grown on a substrate are investigated.

The sensitivity of modern IR micro-spectrometers is suffciently high to permit observation of the cellular spectra even in the presence of the high water background signals. The results reported here might have far-reaching implication for the use of IR-MSP to monitor cell proliferation, drug response, and other cell biological parameters in live cells. In addition to the strong water absorption, another problem arises for spectroscopy of live cells. This problem is due to the fact that IR spectroscopy is always carried out as a ratio measurement of the background and the sample spectra. Since the cell contains less water signal than the background spectrum, which is collected from the aqueous layer around the cell, the ratioed spectrum is overcompensated for the water contribution, which has to be corrected manually.

Nevertheless, good spectra could be obtained (Miljković et al., 2004) for a live cell in growth medium. This spectrum agreed by and large with the spectra obtained from dried cells. However, the spectra of cells in growth medium show a sharp band in the symmetric phosphate stretching region (1085 cm−1) with relatively large intensities throughout the nucleus and the cytoplasm. This band is not due to the growth medium itself, which has no spectral features in this region. The identity of this band is presently unknown, but its presence in both cytoplasm and nucleus suggests that it is due to a short-lived component containing phosphate groups, such as ATP, phosphorylated carbohydrates, or proteins that are particularly prevalent in metabolically active cells.

C. RA-MSP Maps of Individual Cells

The studies reported in this section are aimed at demonstrating the label-free advantages of RA-MSP imaging, which is able to reveal cellular compartmentalization and distribution of subcellular organelles. This research is still in its infancy and is being carried out only in a few laboratories worldwide. Therefore, the quality of the data is still somewhat limited; however, with rapid advances in technology, we expect RA-MSP to become a widely applicable technique for cellular biology.

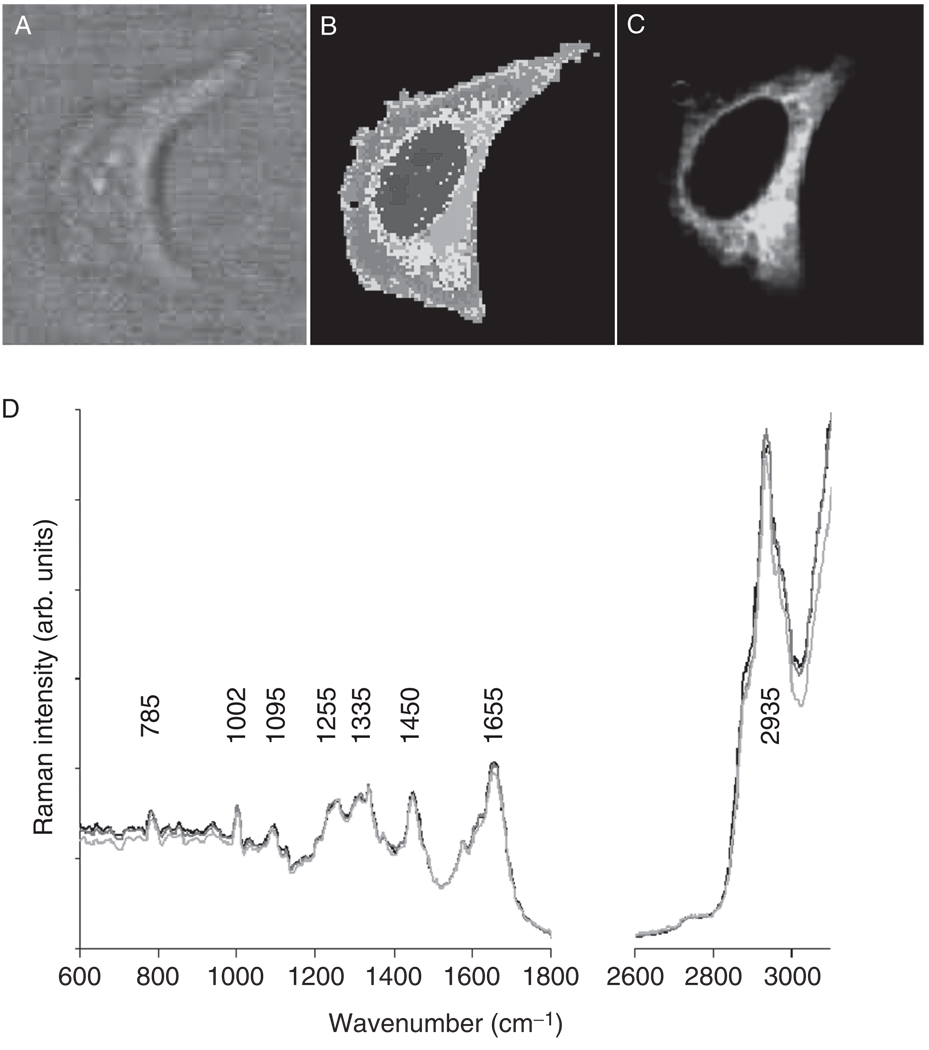

1. High Resolution Raman Images of Cells

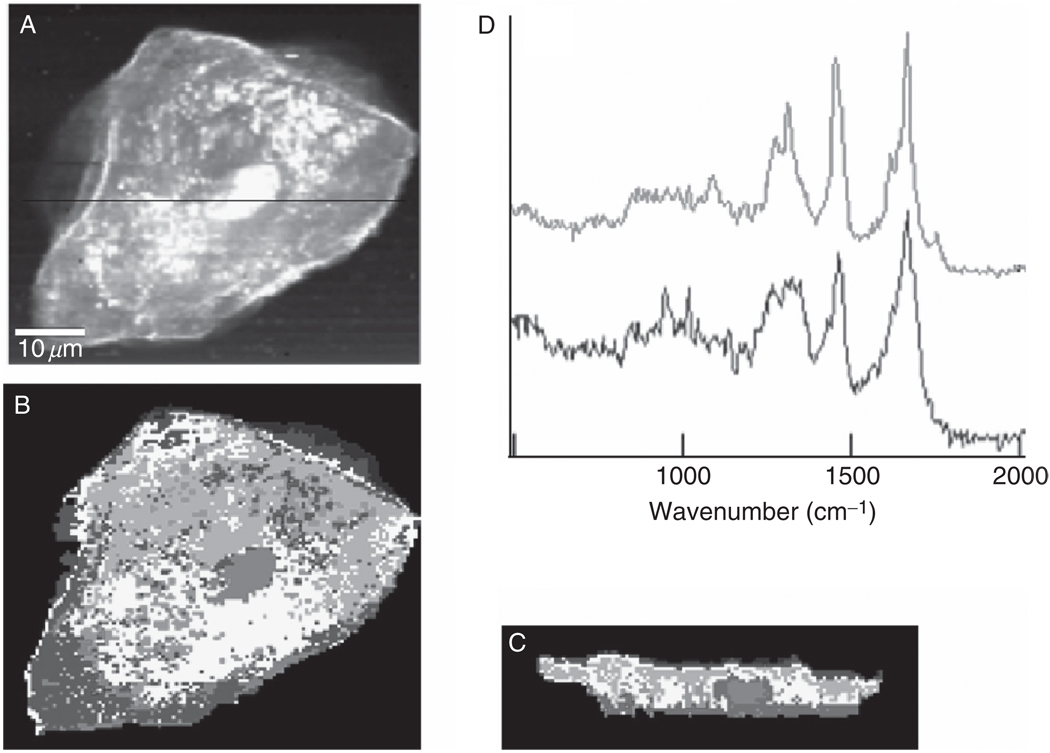

We present in Fig. 9 confocal Raman images of a hydrated exfoliated oral mucosa cell. Fig. 9B is constructed from HCA of 14,400 individual spectra collected using a 60x water immersion objective, and about 15 mW laser power at 514.5 nm excitation. The pixel size in this image is determined by the diffraction limit [see Eqs. (1) and (2)] and is given by about 320 nm laterally, and about 1400 nm axially. Figure 9C shows a X–Z section of the cell; this scan was taken along the direction of the black line in panel A. These images demonstrate the excellent image quality and biochemical information that is available from Raman spectral imaging, followed by multivariate data analysis methods. The red spots in panel B, for example, differ in chemical composition from the surrounding cytoplasm (blue trace in Fig. 9, panel D), and are mostly due to heterogeneously distributed phospholipids (red trace in panel D). From this image, the small size of the pyknotic nucleus in a terminally differentiated squamous cell can be estimated to be less than 10 µm in diameter.

Fig. 9.

Raman images of a human buccal cell. (A) Map of integrated C–H stretching intensities of an oral mucosa cell. (B) Pseudo-color X–Y map of the cell shown in (A), based on HCA of the Raman imaging data set. (C) Corresponding X–Z map, taken as a confocal section along the black line indicated in (A). (D) Normalized mean cluster Raman spectra of phospholipid-rich (top) and protein-rich (bottom) regions of the cytoplasm.

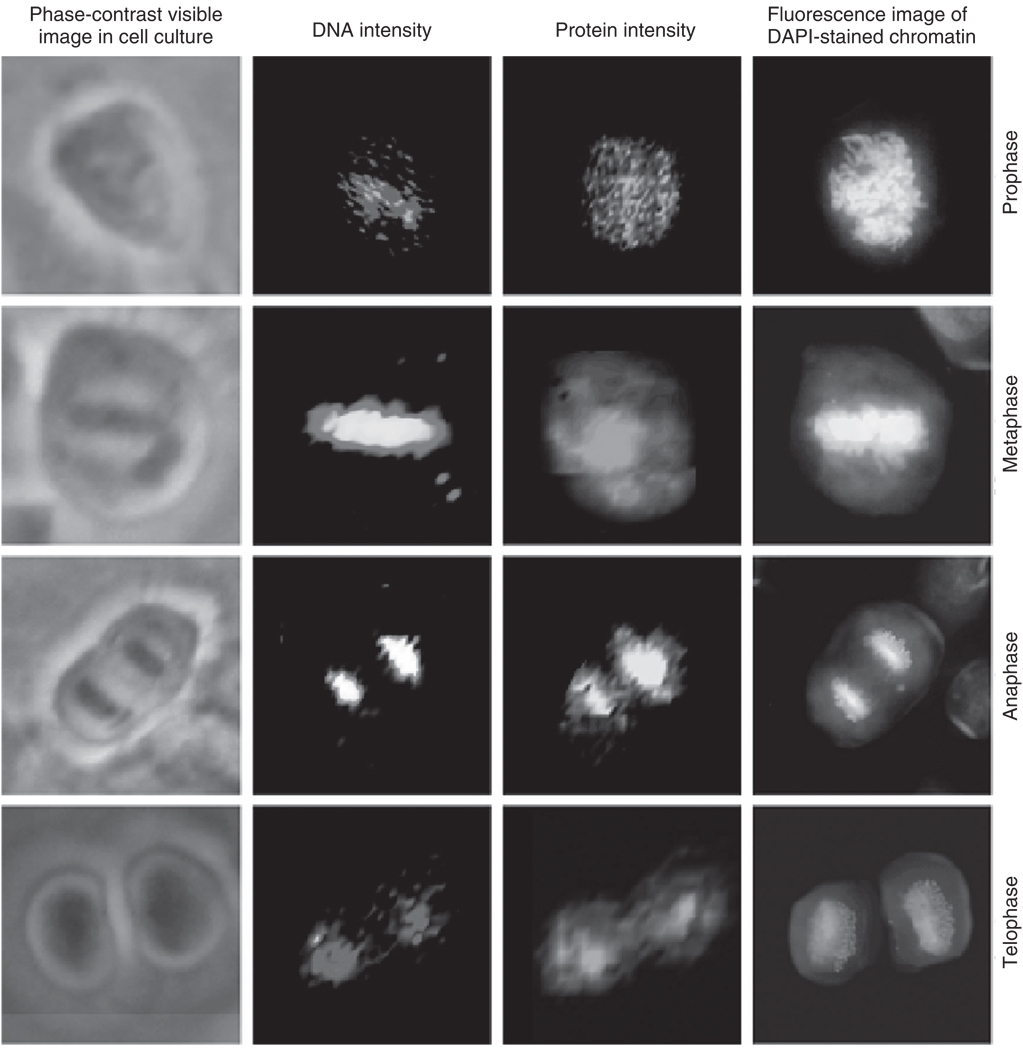

Next, we discuss RA-MSP images of human cells at different stages of mitosis by following the spectral signatures of condensed chromatin, and other biochemical components, utilizing inherent protein and DNA spectral markers. In Section III. B.3, we discussed IR-MSP studies that have concentrated on the detection of variations of a cell’s biomolecular composition during progression through the cell cycle, which precedes mitosis. Here, we present Raman spectral maps for the events that take place during mitosis. The exact sequence of events during mitosis is, of course, well understood from light and fluorescence microscopic studies. Spectral imaging methodology, however, aVords the advantage of monitoring the distribution of biochemical components, using only their inherent vibrational fingerprints without employing any stains or other commonly used probes.

Mitotic cells were selected by microscopic inspection of fixed cells grown on a substrate in culture (Matthäus et al., 2006). The spectral maps reported below for different stages of mitosis do not represent a time course of mitosis of one individual cell, but time points in mitosis of several different cells. Figure 10 shows HeLa cells undergoing the typical stages of mitosis: prophase, metaphase, anaphase, and telophase. The left column of images shows the cells as seen using an inverted phase contrast microscope. The second column shows maps of the nucleic acid Raman band intensity at 785 cm−1, whereas the third column depicts the protein amide I intensity (1655 cm−1). The protein intensity during mitosis is contributed largely by the micro-tubules and the dense histone-packed chromatin. The far right column shows, for comparison, the fluorescence images of the DAPI-stained cells demonstrating the density and distribution of the condensed chromatin within the cell at each of the phases of mitosis.

Fig. 10.

Photomicrographs: Raman and fluorescence (DAPI stain) images of HeLa cells during various phases of mitosis. (Top row) Prophase, (2nd row) metaphase, (3rd row) anaphase, (bottom row) late telophase. All images are collected at 40x magnification. (Column 1) Phase-contrast images of cultured mitotic cells. (Column 2) Raman scattering intensity plots for the DNA scattering intensities. The colors range from black (low intensity) to red to white (high intensity). (Column 3) Raman scattering intensity plots for the protein scattering intensities. The colors range from black (low intensity) to green to yellow (high intensity). (Column 4) Fluorescence images of the DAPI-stained cells.

The chromosomal condensation during metaphase and anaphase, shown in the second and third rows, respectively, is manifested by a large intensity increase of the DNA-related peaks (Matthäus et al., 2006). The bottom row of images in Fig. 10 was taken for a cell in telophase. In contrast to the images of the cells in anaphase and metaphase, the DNA signal is reduced, since the DNA distribution has already become relatively diffuse during this stage of mitosis. However, the protein signals clearly indicate the presence of two newly formed nuclei.

The Raman chromatin intensities correlate very well with the DAPI fluorescence of chromatin. However, the Raman maps are constructed from the Raman scattering signals inherent in the cell, such as the protein/DNA distribution, rather than stains. The Raman images reproduce the chromatin distribution for the prophase, metaphase, and anaphase cells in exquisite detail. However, the chromatin exhibits low signals in the interphase and the late telophase cell since the protein–DNA chromatin complexes are packed much less densely, with a packing ratio of 40, as compared to a metaphase chromosome with a packing ratio of 10,000. Thus, the DNA or chromatin may be too diffuse to yield a detectable Raman signal in the volume probed in these experiments.

2. Label Free Imaging of Cellular Mitochondrial Distribution

This study was undertaken to demonstrate label-free detection of mitochondria in fixed cells. In principle, this methodology can be used in live cells to monitor mitochondrial movement and activity. Since the number of mitochondria in a human cell such as a HeLa cell is very large, detection of one individual mitochondrion is unlikely. However, this was achieved by RA-MSP methods for live yeast cells, which have only a few mitochondria (Huang et al., 2005). Rather, we identified the mitochondria by comparison of Raman spectral clusters with regions exhibiting mitochondria-specific fluorescence emissions (Matthäus et al., 2007). This was accomplished as follows.

HeLa cells were grown on CaF2 substrates using standard cell culture procedures, and the cells adhering to the substrates were formalin-fixed. The cells were subsequently immersed in a drop of BSS solution, and Raman images were collected, as described before, using a water immersion objective, 488 nm excitation and 500 nm×500 nm pixel size. The hyperspectral data sets were analyzed by unsupervised HCA (see Section II.G.2). Figure 11B shows a Raman map of a HeLa cell obtained from HCA of the data set. Although the bright-field image reveals low contrast (since it was taken of a cell in aqueous surrounding), the Raman image reveals the large nucleus typical for actively growing cells. Immediately after Raman data acquisition, a fluorescent stain specific for mitochondria (Mitotracker Green® FM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added to the sample without disturbing the optical settings of the instrument. Fluorescence images were collected ca. 20 min after the stain was added, using the confocal Raman setup described above and 488 nm excitation and significantly lower laser power (1 mW) and a dwell time of 0.2 s per data point.

Fig. 11.

Visualization of cellular mitochondrial distribution. (Panel A) Bright-field image of a HeLa cell in suspension in BSS, taken through a 60x water immersion objective. (Panel B) HCA-based pseudo-color map of cell shown in A. The color assignment is arbitrary and indicate similarities of spectral patterns. (Panel C) Fluorescence image collected after adding Mitotracker Green® FM stain to the buffer surrounding the cell. (Panel D) Mean Raman spectra, extracted from the nuclear regions of three cells used in this study.

Figure 11C shows the fluorescence image of the HeLa cell stained with Mitotracker® for mitochondrial distribution. Bright green areas correspond to high mitochondria content. The highest Mitotracker® fluorescence intensity was observed in the perinuclear region. A comparison of Fig. 11B and C reveals that the regions, from which significant fluorescence due to the Mitotracker® stain is observed, co-localizes very well with the Raman cluster shown in yellow and salmon hues in Fig. 11B. Since the number of spectra contributing to the mean cluster spectra is of the order of several hundred, the S/N ratio for the mean cluster spectra is very good. Furthermore, we (Matthäus et al., 2007) found that for a number of cells analyzed this way, the spectra are very reproducible. For example, the mean cluster spectra observed in the nuclei of three cells show excellent agreement, and even small details in the spectra are reproduced in all of them (Fig. 11D). Given that the Raman maps also can differentiate between nucleus and nucleolus in a cell, we analyzed the resulting means cluster spectra for changes that may be associated directly with the presence of mitochondria.

We found that the mean cluster spectra obtained between nuclear, cytoplasmic, and mitochondrial regions were too similar to interpret spectral changes reliably. All mean cluster spectra (nucleus, nucleolus, mitochondria-rich cytoplasm and remaining cytoplasm) are dominated by protein bands (the amide I vibration at 1655 cm−1 , the extended amide III region between 1270 and 1350 cm−1 , and the sharp phenylalanine ring stretching vibration at 1002 cm−1), which is not surprising, given that the major component in all regions of the cell is protein. Nuclei and nucleoli exhibit a few, weak bands associated with nucleic acids (785, 1095, and 1575 cm−1); although these bands are weak, they are sufficiently reproducible to be detected by HCA.

Apart from spectral features from proteins, lipid contributions may be observed in the spectra from within the cytoplasm. The alkane chains give rise to high C–H stretching intensities between 2850 and 2935 cm−1. In addition, CH2 deformations and the ester linkage C=O stretching are observed around 1735 cm−1 We also observed a Raman band at 715 cm−1 in phospholipid-rich regions that is not present in the spectra from the nuclei. It is possible that this band originates from the symmetric stretching vibration of the N+ (CH3)3 choline group of phosphocholine, which is vastly abundant in membranes.

Although the spectra from the mitochondria-rich regions differ from those of the nucleus and nucleolus, the mean spectra of the mitochondria-rich clusters are very similar to other phospholipid-containing regions of the cytoplasm. Thus, we were not able to reproduce the previous report that associated the spectra of mitochondria in yeast cells with spectral features from phospholipids (Huang et al., 2005). Although we have frequently observed strong phospholipid spectra from small regions in the Raman maps of other cell types, we were not able to co-localize these with the position of mitochondria, and to reproduce these features for the HeLa cell model utilized here.

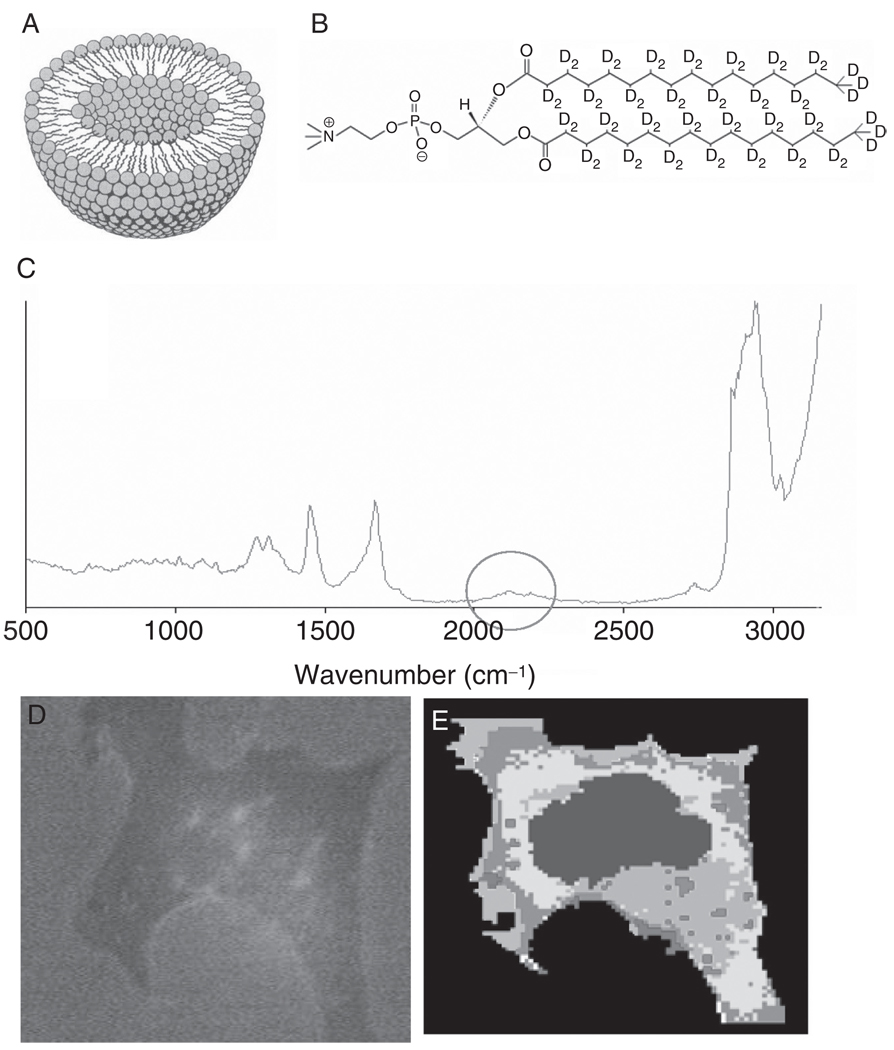

3. Liposome Uptake into Cells

Apart from imaging subcellular features, as discussed in the previous sections, Raman imaging may provide an opportunity to follow the uptake of molecules into cells. One way to distinguish incorporated molecules inside cells is to use deuterated compounds (van Manen et al., 2005). C–D stretching vibrations are shifted away from those of C–H groups by a factor of about the square root of the masses of H and D, or about a factor of 1.4. Thus, C–D stretching vibrations occur around 2150 cm−1, in a region devoid of any signals in the Raman spectra of cells and cellular components (see Fig. 12, panel C). The deuterium “label” is invisible to the cell, since the isotopic species occupies nearly exactly the same volume, and acts chemically nearly identically, to hydrogen atoms.

Fig. 12.

Liposome uptake by cells. (Panel A) Schematic section through a liposome. (Panel B) Structure of DSPC-d70. (Panel C) Raman spectrum obtained from a region of the cell containing deuterated liposomes. The C–D stretching region is shown by the circle. (Panel D) Bright-field image of breast adenocarcinoma (MCF-7) cells incubated for 3 h with TATp-LIP. (Panel E) HCA-based pseudo-color map of cell shown in panel D. Red areas correspond to the highest C–D stretching intensities (possibly due to condensed liposomes), whereas the purple spots inside the cytoplasm indicate small regions of deuterated lipids, possibly due to individual liposomes.

We demonstrate the use of this technique (Matthäus et al., 2008) to investigate the cellular uptake and intracellular fate of lipid-based nanoparticles known as liposomes (Fig. 12A). These are bilayer-based nanospheres with sizes ranging from ∼50 to 300 nm. Currently, liposomes are widely used for drug delivery purposes (Gupta et al., 2005), including intracellular drug and gene delivery (Rao and Gopal, 2006; Serpe et al., 2006). Many aspects related to the detailed mechanisms of the liposome-to-cell interaction remain unresolved. This is especially true for the case of liposomal nanocarriers modified by cell-penetrating peptides, such as the HIV-1 trans-activating transcriptional activator-derived TAT peptide (Gupta et al., 2005). These carrier systems are currently considered a very promising way to bring various drugs, including protein and peptides, into cells (Wadia and Dowdy, 2005). Here we demonstrate the feasibility of Raman imaging to follow the uptake of TAT peptide-modified deuterated liposomes (TATp-LIP).

Deuterated liposomes were prepared according to literature procedures (Dipali et al., 1996; Liang et al., 2004) from a dried lipid film cast from a chloroform solution of DSPC-d70 (Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc., Alabaster, AL, Fig. 12B). This film was hydrated and vortexed with HEPES-buffered saline (HBS), pH 7.4, at a DSPC concentration of 1.6 mM. The resulting liposomes were sized through double stacked 200 nm pore size polycarbonate membranes (Nucleopore). The liposome size was analyzed by using a Coulter N4 MD Submicron Particle Size Analyzer (Coulter Electronics). TATp-liposomes were prepared as follows. Purified TATp was received from Tufts University Core Facility (Boston, MA). TATp peptide was coupled to TATp-PEG2000-PE using published methods (Matthäus et al., 2008). For preparing TATp-liposomes, TATp-PEG2000-PE was added to the lipid film. Liposomes were subsequently sized as described above.

Human breast adenocarcinoma MCF-7 cells were incubated for different time intervals with deuterated LIP and TATp-LIP at a lipid concentration of 2 mg/ml. After the incubation, cells were fixed in a formalin-phosphate-buffered solution and subsequently washed and submerged in phosphate-buffered saline, to maintain the shape of the cells in their aqueous environment.

Figure 12D shows a microscopic image of an MCF-7 cell incubated with TATp-LIP for 6 h. Panel 12E is a pseudo-color map, constructed from the hyperspectral data set using HCA. The cluster analysis is based mainly on the detection of the C–D stretching vibrational signal, observed around 2150 cm−1, and shown in trace 12C. Large amounts of the deuterated phospholipids were found in the cell periphery.

The most important result of this study is that RA-MSP clearly allows for the observation of lipid particle uptake by the cells. This uptake is enormously accelerated by TTAp, confirming previous experiments (Wadia and Dowdy, 2005). The uptake was clearly seen already after 3 h for TATp-LIP and only after 12 h for plain LIP. Although very small deuterated regions can be detected early in an uptake experiment, aggregation or incorporation of the deuterated phospholipids into other membrane structures occurs, resulting in contiguous regions of high deuterium content. To ascertain that the liposomes are observed within the cytoplasm and not just adsorbed on the cell surface, a depth profile in the xz-direction was collected (Matthäus et al., 2008) which indicated that the deuterated liposomes penetrate the cell body. The spectral appearances of the C–D stretching region, with respect to band shapes and peak positions, did not change significantly upon uptake, indicating that the lipid side chains did not undergo substantial conformational changes.

IV. Conclusions

In this chapter, we have reviewed some of the most recent findings on Raman and infrared spectral studies of cells from our laboratory. Over the course of the past 4 years, we have collected spectra from in excess of 10,000 individual cells— both for high spatial resolution studies, in an eVort to understand the spectral consequences of cell biological events, and for establishing data bases for eventual spectral diagnostic algorithms.

Acknowledgment

Partial support of this research from grants CA 81675 and CA 090346 from the National Institutes of Health is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Adams MJ. Chemometrics in Analytical Spectroscopy. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Aten JA, Bakker PJM, Stap J, Boschman GA, Veenhof CHN. DNA double labelling with IdUrd and CldUrd for spatial and temporal analysis of cell proliferation and DNA replication. Histochem. J. 1992;24(5):251–259. doi: 10.1007/BF01046839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boydston-White S, Chernenko T, Regina A, Miljkovic M, Matthaeus C, Diem M. Microspectroscopy of single proliferating HeLa cells. Vibrational Spectrosc. 2005;38(1–2):169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Boydston-White S, Romeo MJ, Chernenko T, Regina A, Miljkovic M, Diem M. Cell-cycle-dependent variations in FTIR micro-spectra of single proliferating HeLa cells: Principal component and artificial neural network analysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1758(7):908–914. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr GL. Resolution limit for infrared microspectroscopy explored with synchrotron radiation. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2001;72(3):1613–1619. [Google Scholar]

- Chan JW, Taylor DS. Micro-Raman spectroscopy detects individual neoplastic and normal hematopoietic cells. Biophys. J. 2006;90:648–656. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.066761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiriboga L, Yee H, Diem M. Infrared spectroscopy of human cells and tissue. Part VII: FT-IR microspectroscopy of DNase- and RNase-treated normal, cirrhotic, and neoplastic liver tissue. Appl. Spectrosc. 2000;54(4):480–485. [Google Scholar]

- Diem M. Introduction to Modern Vibrational Spectroscopy. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Diem M, Boydston-White S, Chiriboga L. Infrared spectroscopy of cells and tissues: Shining light onto a novel subject. Appl. Spectrosc. 1999;53(4):148A–161A. [Google Scholar]

- Diem M, Romeo M, Boydston-White S, Miljkovic M, Matthaeus C. A decade of vibrational micro-spectroscopy of human cells and tissue (1994–2004) Analyst. 2004;129(10):880–885. doi: 10.1039/b408952a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dipali SR, Kulkarni SB. Comparative study of separation of non-encapsulated drugs from liposomes by diVerent methods. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1996;48(11):1112–1115. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1996.tb03904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta B, Levchenko T. Intracellular delivery of large molecules and small particles by cell penetrating proteins and peptides. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2005;57:637–651. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm D, Labischinski H, Schallen G, Naumann D. Classification and identification of bacteria by FT-IR spectroscopy. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1991;137:69–79. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-1-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst PA. Canine Reproduction: A Breeder’s Guide. Loveland: Alpine Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Huang YS, Karashima T. Molecular-level investigation of the structure, transformation, and bioactivity of single living fission yeast cells by time- and space-resolved Raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10009–10019. doi: 10.1021/bi050179w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humecki HJ. Practical Guide to Infrared Microspectroscopy. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Koff A, Cross F, Fisher A, Schumacher J, Leguellec K, Philippe M, Roberts JM. Human cyclin E, a new cyclin that interacts with two members of the CDC2 gene family. Cell. 1991;66(6):1217–1228. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90044-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasch P, Pacifico A, Diem M. Spatially resolved IR microspectroscopy of single cells. Biopolymers. 2002;67(4–5):335–338. doi: 10.1002/bip.10095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasch P, Haensch W. Imaging of colorectal adenocarcinoma using FT-IR microspectroscopy and cluster analysis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1688(2):176–186. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang W, Levchenko TS. Encapsulation of ATP into liposomes by diVerent methods: Optimization of the procedure. J. Microencapsul. 2004;21:151–161. doi: 10.1080/02652040410001673900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthäus C, Boydston-White S. Raman and infrared microspectral imaging of mitotic cells. Appl. Spectrosc. 2006;60(1):1–8. doi: 10.1366/000370206775382758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthäus C, Chernenko T. Label-free detection of mitochondrial distribution in cells by nonresonant Raman micro-spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 2007;93:668–673. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.102061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthäus C, Kale A. New ways of imaging uptake and intracellular fate of liposomal drug carrier systems inside individual cells, based on Raman microscopy. Mol. Pharm. 2008 doi: 10.1021/mp7001158. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messerschmidt RG, Harthcock MA. Infrared Microspectroscopy. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Miljković M, Romeo MJ. Infrared microspectroscopy of individual human cervical cancer (HeLa) cells suspended in growth medium. Biopolymers. 2004;74(1–2):172–175. doi: 10.1002/bip.20066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumann D, Fijala V, Labischinski H, Giesbrecht P. The rapid diVerentiation of pathogenic bacteria using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic and multivariate statistical analysis. J. Mol. Struct. 1988;174:165–170. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley D. Confocal one and two photon fluorescence microscopy. In: Correia DIJJ, W H, editors. “Methods in Cell Biology, Vol. 2: Biophysical Techniques”. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Otto C, Greve J. Progress in instrumentation for Raman micro-spectroscopy and Raman imaging for cellular biophysics. Internet J. Vibrational Spectrosc. 1998;2(3) [Google Scholar]

- Rao NM, Gopal V. Cell biological and biophysical aspects of lipid-mediated gene delivery. Biosci. Rep. 2006;26(4):301–324. doi: 10.1007/s10540-006-9026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo M, MohlenhoV B, Jennings M, Diem M. Infrared micro-spectroscopic studies of epithelial cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006a;1758(7):915–922. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romeo MJ, MohlenhoV B. Infrared microspectroscopy of human cells: Causes for the spectral variance of oral mucosa (buccal) cells. Vibrational Spectrosc. 2006b;42:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.vibspec.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serpe L, Guido M, Canaparo R, Muntoni E, Cavalli R, Panzanelli P, Della Pepal, C., Bargoni A, Mauro A, Gasco MR, Eandi M, Zara GP. Intracellular accumulation and cytotoxicity of doxorubicin with diVerent pharmaceutical formulations in human cancer cell lines. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2006;6(9–10):3062–3069. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2006.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Manen HJ, Kraan YM. Single-cell Raman and fluorescence microscopy reveal the association of lipid bodies with phagosomes in leukocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102(29):10159–10164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502746102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadia JS, Dowdy SF. Transmembrane delivery of protein and peptide drugs by TAT-mediated transduction in the treatment of cancer. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2005;57(4):579–596. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JH. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1963;58(301):236–244. [Google Scholar]

- Wood BR, Chiriboga L. FTIR mapping of the cervical transformation zone, squamous and glandular epithelium. Gynecol. Oncol. 2004;93(4):59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]