Abstract

Background

Etomidate is a sedative-hypnotic that is often used in critically ill patients because it provides superior hemodynamic stability. However it also binds with high affinity to 11β-hydroxylase, potently suppressing synthesis of steroids by the adrenal gland that are necessary for survival. We report the results of studies to define the pharmacology of (R)-ethyl 1-(1-phenylethyl)-1H-pyrrole-2-carboxylate (carboetomidate), a pyrrole analogue of etomidate specifically designed not to bind with high affinity to 11β-hydroxylase.

Methods

The hypnotic potency of carboetomidate was defined in tadpoles and rats using loss of righting reflex assays. Its ability to enhance wild-type α1β2γ2L and etomidate-insensitive mutant α1β2(M286W)γ2L human γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor activities was assessed using electrophysiological techniques. Its potency for inhibiting in vitro cortisol synthesis was defined using a human adrenocortical cell assay. Its effects on in vivo hemodynamic and adrenocortical function were defined in rats.

Results

Carboetomidate was a potent hypnotic in tadpoles and rats. It increased currents mediated by wild-type, but not etomidate-insensitive mutant γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. Carboetomidate was three orders of magnitude less potent an inhibitor of in vitro cortisol synthesis by adrenocortical cells than was etomidate. In rats, carboetomidate caused minimal hemodynamic changes and did not suppress adrenocortical function at hypnotic doses.

Conclusions

Carboetomidate is an etomidate analogue that retains many of etomidate’s beneficial properties, but is dramatically less potent as an inhibitor of adrenocortical steroid synthesis. Carboetomidate is a promising new sedative-hypnotic for potential use in critically ill patients in whom adrenocortical suppression is undesirable.

Introduction

Etomidate is an intravenous (IV) sedative-hypnotic that is used to induce general anesthesia and is distinguished from other agents by its minimal effects on cardiovascular function. 1-4 Consequently, it is often used in patients who are elderly or critically ill. Etomidate contains an imidazole ring and in common with many other imidazole-containing drugs, it suppresses the synthesis of adrenocortical steroids. 5-11 This suppression occurs even with administration of subhypnotic etomidate doses and is extremely long lasting. 12,13 Such “chemical adrenalectomy” precludes etomidate administration by continuous infusion to maintain anesthesia in the operating room (or sedation in the intensive care unit) and has raised serious concerns regarding the administration of even a single bolus for anesthetic induction in critically ill patients. 14-19

This led us to search for solutions to the problem of etomidate-induced adrenocortical suppression. In a previous study, we tested a pharmacokinetic strategy for reducing the duration of adrenocortical suppression following bolus administration. We synthesized an analogue of etomidate (methoxycarbonyl-etomidate) designed to be rapidly metabolized by esterases and demonstrated that it does not produce prolonged adrenocortical suppression in rats following bolus administration. 20

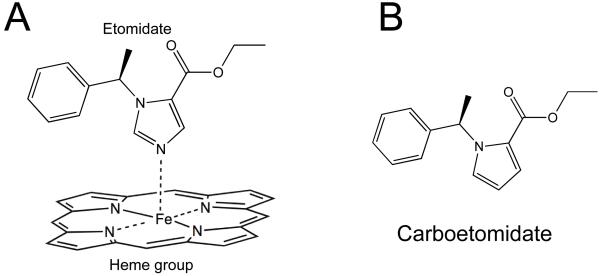

We have also considered pharmacodynamic strategies for reducing etomidate-induced adrenocortical suppression. Etomidate suppresses adrenocortical steroid synthesis by inhibiting 11β-hydroxylase, a cytochrome P450 enzyme that is required for the synthesis of cortisol, corticosterone, and aldosterone. 21 X-ray crystallographic studies of other imidazole-containing drugs to cytochrome P450 enzymes indicate that high affinity binding occurs because the basic nitrogen in the drug’s imidazole ring coordinates with the heme iron in the enzyme’s active site; cytochrome P450 enzymes (including 11β-hydroxylase) contain heme prosthetic groups at their active sites. 22-24 Although 11β-hydroxylase has not yet been crystallized nor its interaction with etomidate precisely defined, homology modeling studies suggest that high affinity binding of etomidate to 11β-hydroxylase also involves coordination between the drug’s basic nitrogen and the enzyme’s heme iron (figure 1A). 25 This led us to hypothesize that high affinity binding to 11β-hydroxylase (and thus adrenolytic activity) could be “designed out” of etomidate without disrupting potent anesthetic and γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor activities by replacing this nitrogen with other chemical groups that cannot coordinate with heme iron. Based on this hypothesis, we have designed and synthesized (see Appendix 1) (R)-ethyl 1-(1-phenylethyl)-1H-pyrrole-2-carboxylate (carboetomidate) as the lead compound in a new class of pyrrole-based sedative-hypnotic analogues of etomidate designed not inhibit adrenocortical function at pharmacologically relevant doses (figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Hypothesized attractive interaction between the basic nitrogen in etomidate’s imidazole ring and the heme iron at 11β-hydroxylase’s active site. (B) Structure of carboetomidate.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal studies were conducted in accordance with rules and regulations of the Subcommittee on Research Animal Care at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. Early prelimb-bud stage Xenopus laevis tadpoles and adult female Xenopus laevis frogs were purchased from Xenopus 1 (Ann Arbor, MI). Tadpoles were maintained in our laboratory and frogs were maintained in the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Comparative Medicine animal care facility. Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (300-500 gm) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) and housed in the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Comparative Medicine animal care facility.

Blood draws and IV drug administrations used a lateral tail vein IV catheter (24 gauge, 19 mm) placed under brief (approximately 1-5 min) sevoflurane or isoflurane anesthesia delivered using an agent specific variable bypass vaporizer with continuous gas monitoring. Animals were weighed immediately prior to IV catheter placement and were allowed to fully recover from inhaled anesthetic exposure prior to study. During all studies, rats were placed on a warming stage (Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT) that our previous studies showed maintains rectal temperatures between 36-38 °C in anesthetized rats. 20

Loss of Righting Reflex (LORR)

Tadpoles

Groups of 5 early prelimb-bud stage Xenopus laevis tadpoles were placed in 100 ml of oxygenated water buffered with 2.5 mM Tris HCl buffer (pH = 7.4) and containing a concentration of carboetomidate ranging from 1 – 40 μM. Tadpoles were manually tipped every 5 min with a flame polished pipette until the response stabilized. Tadpoles were judged to have LORR if they failed to right themselves within 5 seconds after being turned supine. At the end of each study, tadpoles were returned to fresh water to assure reversibility of hypnotic action. The EC50 for LORR was determined from the carboetomidate concentration-dependence of LORR using the method of Waud. 26

Rats

Rats were briefly restrained in a 3 inch diameter, 9 inch long acrylic chamber with a tail exit port. The desired dose of carboetomidate in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; typically at 40 mg/ml) was injected through a lateral tail vein catheter followed by an approximately 1 ml normal saline flush. After injection, rats were removed from the restraint device and turned supine. A rat was judged to have LORR if it failed to right itself (onto all four paws) after drug administration. A stop-watch was used to measure the duration of LORR, which was defined as the time from carboetomidate injection until the animal spontaneously righted itself. The ED50 for LORR upon bolus administration was determined from the dose-dependence of LORR using the method of Waud. 26

Onset time for LORR was determined separately by injecting rats with 28 mg/kg carboetomidate (40 mg/ml in DMSO) or 4 mg/kg etomidate (5.7 mg/ml in DMSO) through a lateral tail vein catheter followed by an approximately 1 ml normal saline flush. Following injection, rats were immediately removed from the restraint device and repeatedly turned supine until they no longer spontaneously righted. The onset time was defined as the time from injection until LORR occurred.

GABAA Receptor Electrophysiology

Adult female Xenopus laevis frogs were anesthetized with 0.2% tricaine (ethyl-maminobenzoate) and hypothermia. Ovary lobes were then excised through a small laparotomy incision and placed in OR-2 solution (82 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.5) containing collagenase 1A (1 mg/ml) for 3 hrs to separate oocytes from connective tissue.

Stage 4 and 5 oocytes were injected with messenger RNA encoding the α1, β2 (or β2(M286W)), and γ2L subunits of the human GABAA receptor (~ 40 ng of messenger RNA total at a subunit ratio of 1:1:2). This messenger RNA was transcribed from complementary DNA encoding for GABAA receptor α1, β2 (or β2M286W), and γ2L subunits using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE High Yield Capped RNA Transcription Kit (Ambion, Austin, Tx). Injected oocytes were incubated in ND-96 buffer solution (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5) containing 50 U/ml of penicillin and 50 μg/ml of streptomycin at 17°C for at least 18 hours before electrophysiological experiments.

All electrophysiological recordings were performed using the whole cell two-electrode voltage-clamp technique. Oocytes were placed in a 0.04 ml recording chamber and impaled with capillary glass electrodes filled with 3 M KCl and possessing open tip resistances less than 5 MΩ. Oocytes were then voltage-clamped at −50 mV using a GeneClamp 500B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA), and perfused with ND-96 buffer at a rate of 4-6 ml/min. Buffer perfusion was controlled using a six-channel valve controller (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) interfaced with a Digidata 1322A data acquisition system (Axon Instruments), and driven by a Dell personal computer (Round Rock, TX). Current responses were recorded using Clampex 9.2 software (Axon Instruments), and processed using a Bessel (8-pole) low pass filter with a cutoff at 50 Hz using Clampfit 9.2 software (Axon Instruments).

For each oocyte, the concentration of GABA that produces 5-10% of the maximal current response (EC5-10 GABA) was determined by measuring the peak current responses evoked by a range of GABA concentrations (in ND-96 buffer) and comparing them to the maximal peak current response evoked by 1 mM GABA. The effect of carboetomidate on EC5-10 GABA-evoked currents was then assessed by first perfusing the oocyte with EC5-10 GABA for 90 s and measuring the control peak evoked current. After a 5 min recovery period, the oocyte was perfused with carboetomidate for 90 s and then with EC5-10 GABA plus carboetomidate for 90 s and the peak evoked current was measured again. After a 15 min recovery period, the control experiment (i.e. no carboetomidate) was repeated to test for reversibility. A longer recovery period after carboetomidate exposure was used to facilitate washout of the drug. The peak current response in the presence of carboetomidate was then normalized to the average peak current response of the two control experiments. Carboetomidate-induced potentiation was quantified from the normalized current responses in the presence versus absence of carboetomidate.

Rat Hemodynamics

The effects of hypnotics on rat hemodynamics were defined as previously described. 20 Femoral arterial catheters, tunneled between the scapulas, were preimplanted by the vendor (Charles River Laboratories). Animals were fully recovered from the placement procedure upon arrival. During housing and between studies, catheter patency was maintained with a heparin (500 U/ml) and hypertonic (25%) dextrose locking solution, which was withdrawn prior to each use and replaced just after.

On the day of study and following weighing and lateral tail vein IV catheter placement, rats were restrained in the acrylic tube with a tail exit port and allowed to acclimate for approximately 10 to 20 min prior to data collection. The signal from the pressure transducer (TruWave, Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA) was amplified using a custom built amplifier (AD620 operational amplifier, Jameco Electronics, Belmont, CA) and digitized (1 kHz) using a USB-6009 data acquisition board (National Instruments, Austin, TX) without additional filtering. All data were acquired and analyzed using LabView Software (version 8.5 for Macintosh OS X; National Instruments).

Data used for blood pressure analysis were recorded for 5 min immediately prior to hypnotic administration and for 15 min thereafter. Carboetomidate (40 mg/ml) dissolved in DMSO, etomidate (5.7 mg/ml) dissolved in DMSO, or DMSO vehicle alone as a control was administered through the tail vein catheter followed by approximately 1 ml normal saline flush.

Inhibition of In Vitro Cortisol Synthesis

In vitro cortisol synthesis was measured using the human adrenocortical cell line H295R (NCI-H295R; ATCC #CRL-2128). Aliquots of 105 cells per well were grown in 12-well culture plates with 2 ml of growth medium (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/F12 supplemented with 1% insulin, transferrin, selenium, and linoleic acid, 2.5% NuSerum, and Pen/Strep). When cells reached near confluence (typically 48-72 hr), the growth medium was replaced with assay medium (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium/F12 supplemented with 0.1% insulin, transferring, selenium containing antibiotics and 20 μM forskolin) that contained etomidate or carboetomdiate. After 48 hr, 1.2 ml of assay medium was collected from each well, centrifuged to pellet any cells or debris, and the cortisol concentration in the supernatant quantified by ELISA using commercially available 96-well kits based on horseradish peroxidase-conjugated cortisol in a competitive antibody binding assay (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, #KGE008).

Rat Adrenocortical Suppression

Immediately following weighing and IV catheter placement, dexamethasone (0.2 mg/kg IV; American Regent, Shirley, NY) was administered to each rat to inhibit endogenous adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) release, to suppress baseline corticosterone production, and to inhibit the variable stress response to restraint and handling. Two hours following dexamethasone treatment, blood was drawn (for baseline measurement of serum corticosterone concentration) and a second dose of dexamethasone (0.2 mg/kg) was administered along with IV carboetomidate, etomidate, or DMSO vehicle as a control. The concentrations of carboetomidate and etomidate in DMSO were 40 mg/ml and 5.7 mg/ml, respectively. Immediately after hypnotic or vehicle administration, ACTH1-24 (25 μg/kg; Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO) was given intravenously to stimulate corticosterone production. Fifteen minutes later, a second blood sample was drawn to measure the ACTH1-24-stimulated serum corticosterone concentration. ACTH1-24 was dissolved in 1 mg/ml in deoxygenated water as stock, aliquoted, and frozen (−20 °C); a fresh aliquot was thawed just prior to each use. Rats in all three groups (carboetomidate, etomidate and vehicle) received the same volume of DMSO (350 μl/kg).

Corticosterone concentrations in blood serum were determined as previously reported. 20 Blood samples were allowed to clot at room temperature (10 to 60 min) before centrifugation at 3500g for 5 min. Serum was carefully expressed from any resulting superficial fibrin clot using a clean pipette tip prior to a second centrifugation at 3500g for 5 min. Following the second centrifugation, the resultant clot-free serum layer was transferred to a fresh vial for a final, high-speed centrifugation (16000g, for 5 min) to pellet any contaminating red blood cells or particulates. The serum was transferred to a clean vial and promptly frozen (−20 °C) pending corticosterone measurement. Following thawing and heat inactivation of corticosterone binding globulins (65 °C for 20 min), serum baseline and ACTH1-24 stimulated corticosterone concentrations were quantified using an Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay (ELISA) (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Webster, TX) and a 96-well plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Statistical Analysis

All data are reported as mean +/− SD. Statistical analysis and curve fitting (using linear or nonlinear least squares regression) were done using either Prism v4.0 for the Macintosh (GraphPad Software, Inc., LaJolla, CA) or Igor Pro 4.01 (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). P-value < 0.05 indicates statistical significance unless otherwise indicated. For multiple comparisons of physiological data derived from rats, we performed a one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Bonferroni post–test (which relies on an unpaired t-test with a Bonferroni correction).

Results

Loss of Righting Reflexes in Tadpoles and Rats by Carboetomidate

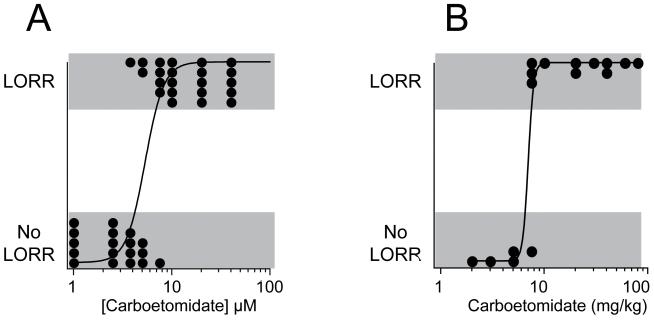

Figure 2A shows the carboetomidate concentration-response relationship for LORR in Xenopus laevis tadpoles. The fraction of tadpoles that had LORR increased with carboetomidate concentration and at the highest concentrations studied (10 – 40 μM) all tadpoles had LORR. All tadpoles that had LORR recovered their righting reflexes when removed from carboetomidate and returned to fresh water. From the concentration-response data, carboetomidate’s anesthetic EC50 was determined to be 5.4 ± 0.5 μM.

Figure 2.

(A) Carboetomidate concentration-response curve for loss of righting reflex (LORR) in tadpoles. Each data point represents the result from a single tadpole. The curve is a fit of the data set using the method of Waud 26 yielding an EC50 of 5.4 ± 0.5 μM. (B) Carboetomidate dose-response curve for LORR in rats. Each data point represents the results from a single rat. The curve is a fit of the data set using the method of Waud 26 yielding an ED50 of 7 ± 2 mg/kg.

Intravenous administration of carboetomidate also produced LORR in Sprague Dawley rats. Figure 2B shows the carboetomidate dose-response relationship for LORR in rats following IV bolus administration. The fraction of rats that had LORR increased with the dose. At the highest doses, all rats had LORR and there was no obvious toxicity. From these data, the ED50 for LORR was determined to be 7 ± 2 mg/kg. We noted that the onset time for LORR with carboetomidate was slower than we had previously observed with etomidate. 20 We quantified this difference using equi-hypnotic doses of carboetomidate and etomidate (28 mg/kg and 4 mg/kg, respectively; 4 X ED50 for LORR). 20 The onset time for LORR with carboetomidate was 33 ± 22 sec (n = 10; range 10 – 63 sec) as compared to 4.5 ± 0.6 sec (n = 4; range 4 – 5 sec) with etomidate.

Figure 3 shows the relationship between the carboetomidate dose and the duration of LORR following IV bolus administration to Sprague Dawley rats. The duration of LORR increased approximately linearly with the logarithm of the dose with a slope of 16 ± 4 min/(log mg/kg).

Figure 3.

The duration loss of righting reflex (LORR) in rats increased with the logarithm of the carboetomidate dose. The slope of this relationship was 16 ± 4 min/(log mg/kg) (r2 = 0.64).

Modulation by Carboetomidate of Wild-type α1β2γ2L and Etomidate-insensitive α1β2M286Wγ2L GABAA receptors

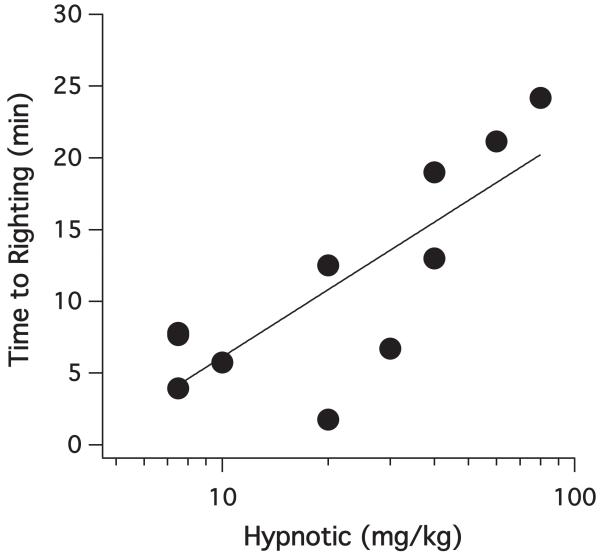

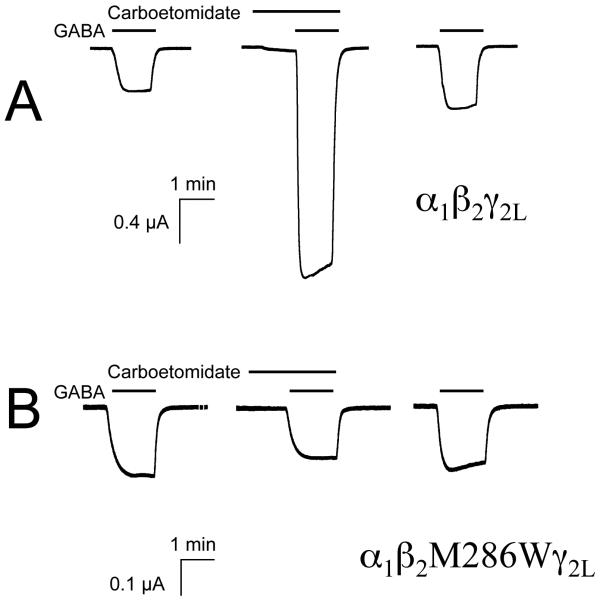

Figure 4 shows representative electrophysiological traces elicited by EC5-10 GABA in the absence or presence of 10 μM carboetomidate. Figure 4A shows traces that were mediated by wild-type α1β2γ2L GABAA receptors whereas Figure 4B shows traces that were mediated by etomidate-insensitive mutant α1β2(M286W)γ2L GABAA receptors. Carboetomidate significantly enhanced currents mediated by wild-type receptors (390 ± 80%) but did not enhance currents mediated etomidate-insensitive mutant receptors (−9 ± 16%).

Figure 4.

Carboetomidate modulation of human γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor function. (A) Representative traces showing reversible enhancement by 10 μM carboetomidate of currents mediated by wild-type receptors when evoked by EC5-10 γ-aminobutyric acid. (B) Representative traces showing minimal of enhancement by 10 μM carboetomidate of currents mediated by etomidate-insensitive mutant receptors when evoked by EC5-10 γ-aminobutyric acid.

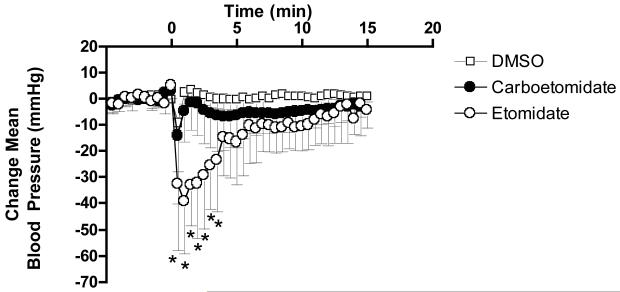

Hemodynamic Actions of Carboetomidate Versus Etomidate in Rats

Figure 5 shows the effects of 14 mg/kg carboetomidate (n=7), 2 mg/kg etomidate (n=6), and DMSO vehicle (n=4) on mean arterial blood pressure in rats. For carboetomdiate and etomidate, these are equi-hypnotic doses. During the study period, carboetomidate’s effect on mean blood pressure was not significantly greater than that of DMSO vehicle alone, (P > 0.05 by two-way ANOVA). However at times from 30 to 210 sec following administration, etomidate significantly reduced mean blood pressure relative to vehicle. Baseline mean blood pressures for vehicle, carboetomidate, and etomidate groups were similar (P = 0.15 by ANOVA) at 114+/−5, 116+/−9, and 127+/−17 mmHg, respectively.

Figure 5.

The effects of 14 mg/kg carboetomidate (n=7), 2 mg/kg etomidate (n=6), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) vehicle alone (n=4) on mean blood pressure in rats. Hypnotics were given at doses equal to twice their respective ED50s for loss of righting reflex in DMSO vehicle. All rats received the same quantity of DMSO vehicle (350 μl/kg). Hypnotic in DMSO vehicle or DMSO vehicle alone was injected at time 0. Each data point represents the average (± SD) change in mean blood pressure during each 30 s epoch. *, P < 0.05 versus DMSO vehicle alone.

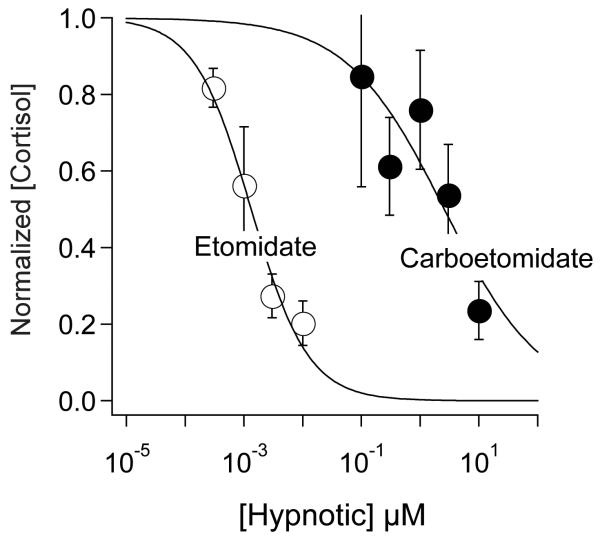

Inhibition by Carboetomidate and Etomidate of Human Adrenocortical Carcinoma Cell Cortisol Synthesis

Figure 6 shows the carboetomidate and etomidate concentration-response curves for inhibition of cortisol synthesis by human adrenocortical cells. Although both hypnotics inhibited cortisol synthesis in a concentration-dependent manner, the concentration ranges over which this inhibition occurred differed by three orders of magnitude. The half maximal inhibitory concentration for carboetomidate and etomidate were calculated from these data sets to be 2.6 ± 1.5 μM and1.3 ± 0.2 nM, respectively.

Figure 6.

The effects of carboetomidate and etomidate on cortisol synthesis by human adrenocortical carcinoma cells. The curves are fits of each data set to a Hill equation yielding half maximal inhibitory concentrations of 2.6 ± 1.5 μM and1.3 ± 0.2 nM for carboetomidate and etomidate, respectively. Each data point is the average (± SD) of three measurements. The control cortisol concentration was 0.86 ± 020 ng/ml.

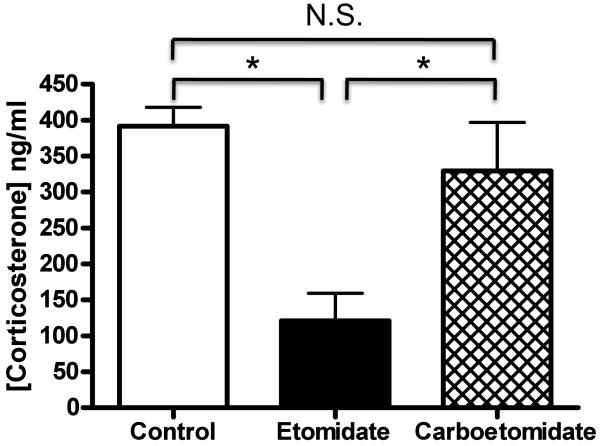

Adrenocortical Suppression in Rats Upon Administration of Carboetomidate Versus Etomidate

Serum corticosterone concentrations were measured in dexamethasone pre-treated rats before (baseline) and 15 minutes after they received ACTH1-24 and carboetomidate, etomidate, or DMSO vehicle control. Baseline serum corticosterone concentrations in rats (n=12) averaged 39 ± 49 ng/ml and were not significantly different among the three groups (carboetomidate, etomidate, and control). Administration of ACTH1-24 stimulated adrenocortical steroid production in all three groups. However figure 7 shows that serum corticosterone concentrations varied among the three groups 15 minutes after ACTH1-24 administration. Rats given carboetomidate had serum corticosterone concentrations that were significantly higher than those given an equi-hypnotic dose of etomidate and not significantly different from those given vehicle.

Figure 7.

Adrenocorticotropic hormone1-24-stimulated serum corticosterone concentrations in rats 15 min after administration of vehicle, 2 mg/kg etomidate, or 14 mg/kg carboetomidate. Hypnotics were given at doses equal to twice their respective ED50s for loss of righting reflex. Four rats were studied in each group. Average serum corticosterone concentrations (± SD) were 390 ± 50 ng/ml, 120 ± 80 ng/ml, and 330 ± 70 ng/ml following administration of dimethyl sulfoxide vehicle (control), etomidate, and carboetomidate, respectively. *, P < 0.05, N.S., no significant difference.

Discussion

Carboetomidate is a pyrrole analogue of etomidate that retains etomidate’s hypnotic action, GABAA receptor modulatory activity, and hemodynamic stability. However, it is three orders of magnitude less potent an inhibitor of adrenocortical cortisol synthesis than etomidate and unlike etomidate, it does not suppress adrenocortical function in rats at hypnotic doses.

Etomidate suppresses adrenocortical function primarily by inhibiting 11β-hydroxylase (CYP11B1), a member of the cytochrome P450 superfamily of enzymes. 11β-hydroxylase is required for the synthesis of cortisol, corticosterone, and aldosterone. This suppression occurs at very low etomidate concentrations, which is thought to reflect very high affinity of etomidate to the enzyme’s active site. 11,25 We designed carboetomidate based on the hypothesis that etomidate binds with high affinity to 11β-hydroxylase because the basic nitrogen in its imidazole ring coordinates with the active site’s heme iron. This interaction has been observed in the binding of other imidazole-containing drugs to various cytochrome P450 enzymes using crystallographic techniques. For example, the inhibitor 4-(4-chlorophenyl)imidazole binds to the enzyme 2B4’s active site in a single orientation with the basic nitrogen of its imidazole ring coordinated to the enzyme’s heme iron at a bond distance of 2.14 Å. 22 This binding triggers a conformational transition in which the enzyme closes tightly around the bound ligand. Similarly, imidazole-containing antifungal agents bind within the active sites of CYP130 and CYP121 where they form a coordination bond between their basic nitrogens and the enzymes’ heme iron. 23,24 Evidence of such coordination has also been found using spectroscopic techniques as the heme group serves as a chromophore that undergoes a characteristic spectral shift when a coordination bond is formed with an imidazole-containing inhibitor. 23,27-29 Although etomidate’s interactions with 11β-hydroxylase have not been defined experimentally using crystallographic or spectroscopic techniques, in silico homology modeling suggests that coordination between the hypnotic’s basic nitrogen and the enzyme’s heme iron also contributes to high affinity binding. 25

We used an adrenocortical carcinoma cell assay to compare the inhibitory potencies of carboetomidate and etomidate. This assay has previously been used to compare the potencies with which drugs inhibit the synthesis of adrenocortical steroids. 30-32 Our studies showed that carboetomidate is three orders of magnitude less potent an inhibitor of cortisol synthesis than is etomidate. This is consistent with an important role for the hypnotic’s basic nitrogen in stabilizing binding to the enzyme and provides strong evidence that high affinity binding of etomidate to 11β-hydroxylase can be designed out of etomidate by replacing this nitrogen with other chemical groups (in this case, CH) that cannot coordinate with heme iron. As a consequence of its low adrenocortical inhibitory potency, carboetomidate failed to inhibit ACTH1-24-stimulated production of corticosterone in rats when given as a bolus at a hypnotic dose.

Although carboetomidate is three orders of magnitude less potent an inhibitor of in vitro cortisol synthesis than is etomidate, it is only modestly less potent as a hypnotic. It has 1/3rd and 1/7th the hypnotic potency of etomidate in tadpoles 33 and rats 20, respectively. These results provide proof-of-principle that one may alter anesthetic structure in order to dramatically reduce potency for producing an undesirable side effect without greatly impacting hypnotic potency.

In common with etomidate, carboetomidate significantly enhances the function of wild-type α1β2γ21 GABAA receptors.34 Thus, it seems very likely that carboetomidate also produces hypnosis via actions on the GABAA receptor. Previous electrophysiological studies of the GABAA receptor have shown that a mutation in the beta subunit at the putative etomidate binding site (M286W) nearly completely abolishes etomidate enhancement. 35 Our studies show that this mutation also abolishes enhancement by carboetomidate, suggesting that carboetomidate modulates GABAA receptor function by binding to the same site on the GABAA receptor as etomidate.

The magnitude of potentiation that we observed with 10 μM carboetomidate (390 ± 80%) in the present study is no greater than that observed in our previous study with 4 μM etomidate (660 ± 240%). This implies that carboetomidate is less potent and/or efficacious at the GABAA receptor than is etomidate. This may explain why a higher concentration (in our tadpole assay) and dose (in our rat assay) of carboetomidate than etomidate is needed to produce LORR. It also indicates that the basic nitrogen in etomidate’s imidazole ring contributes modestly to etomidate’s action on GABAA receptors.

The onset of LORR was slower with carboetomidate than etomidate. The reason for this is unclear. However as both hypnotics potentiate the GABAA receptor, it seems likely that onset is delayed because carboetomidate reaches its site of action in the brain more slowly than etomidate.

Carboetomidate was conceived as a pharmacodynamic solution to the problem of etomidate-induced adrenocortical suppression as it was designed not to bind to 11β-hydroxylase with high affinity. We recently described the results of studies on methoxycarbonyl etomidate, an etomidate analogue developed as a pharmacokinetic solution to this same problem. 20 Methoxycarbonyl etomidate is very rapidly metabolized by esterases and, therefore, produces hypnosis of extremely short duration and does not cause prolonged suppression of adrenocortical function following administration. In contrast, carboetomidate produces hypnosis that is similar in duration to etomidate and propofol (when given at equivalent multiples of their respective ED50 values for LORR) without inhibiting steroid synthesis at a hypnotic dose.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants R01-GM087316 and P01-GM58448 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; the Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research, Rochester, Minnesota; Partners Healthcare, Boston, MA; and the Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care, and Pain Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

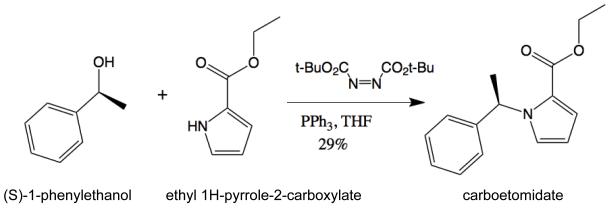

Appendix 1

Synthesis of (R)-Ethyl 1-(1-phenylethyl)-1H-pyrrole-2-carboxylate (carboetomidate)

Following a procedure described for Mitsunobu alkylation of imidazoles11, a solution of (S)-1-phenylethanol (135 mg, 1.10 mmol, >99% entaniomeric ratio) in dry tetrahydrofuran (2 ml) was added dropwise to a stirred solution of ethyl 1H-pyrrole-2-carboxylate (140 mg, 1.00 mmol) and triphenylphosphine (340 mg, 1.30 mmol) in dry THF (3 ml) in an argon atmosphere at room temperature (Figure 8). Then a solution of di-tert-butyl azodicarboxylate (304 mg, 1.32 mmol) in dry THF (2 ml) was added, and the reaction mixture was allowed to stir at room temperature overnight. The reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was mixed with diethyl ether (5 ml) and stirred for 2 h. The residue (Ph3PO and hydrazo ester) were collected and washed with diethyl ether (3 × 2 ml). The filtrate was evaporated under reduced pressure to yield a residue, which was purified by flash chromatography (hexanes/CH2Cl2 = 7:3) on silica gel to give a colorless viscous liquid (71 mg, 29% yield): IR (KBr, cm−1): 737, 1106, 1231, 1700, 2980, 3328; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.30 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.80 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 4.17–4.28 (m, 2H), 6.17 (dd, J = 4.0, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 6.60 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 6.98–7.01 (m, 2H), 7.12–7.14 (m, 2H), 7.20–7.25 (m, 1H), 7.28–7.32 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 14.6, 22.3, 55.5, 60.0, 108.5, 118.5, 122.6, 125.5, 126.4, 127.5, 128.7, 143.3, 161.4; LC-MS observed 244.10, calculated 244.10 for C15H18NO2 (M + H); Analytical calculation for C, 74.05; H, 7.04; N, 5.76. Found: C, 74.25; H, 6.94; N, 5.66. The final product was determined to be essentially enantiomerically pure (>99% ee) by chiral high-pressure liquid chromatography analysis utilizing a AD-H column, isocratic eluent of hexane and isopropanol (97:3), a flow rate of 1 ml/min and detection at l = 220 nm. See figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which shows the analysis of enantiomerically pure carboetomidate produced as described above using (S)-1-phenylethanol. For comparison, the figure also shows the analysis of racemic carboetomidate produced in a similar manner using racemic 1-phenylethanol.

Figure 8.

Synthesis of carboetomidate

Footnotes

Summary Statement: Carboetomidate is an etomidate analogue that enhances γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors, produces hypnosis, is 3 orders of magnitude less potent inhibitor of in vitro cortisol synthesis, and does not suppress in vivo adrenocortical function.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The Massachusetts General Hospital has submitted a patent application for carboetomidate and related analogues. Six authors (Raines, Cotten, Forman, Cuny, Husain, and Miller), and their respective laboratories, departments, and institutions could receive royalties relating to the development or sale of these drugs.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gooding JM, Weng JT, Smith RA, Berninger GT, Kirby RR. Cardiovascular and pulmonary responses following etomidate induction of anesthesia in patients with demonstrated cardiac disease. Anesth Analg. 1979;58:40–1. doi: 10.1213/00000539-197901000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Criado A, Maseda J, Navarro E, Escarpa A, Avello F. Induction of anaesthesia with etomidate: Haemodynamic study of 36 patients. Br J Anaesth. 1980;52:803–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/52.8.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ebert TJ, Muzi M, Berens R, Goff D, Kampine JP. Sympathetic responses to induction of anesthesia in humans with propofol or etomidate. Anesthesiology. 1992;76:725–33. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199205000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarkar M, Laussen PC, Zurakowski D, Shukla A, Kussman B, Odegard KC. Hemodynamic responses to etomidate on induction of anesthesia in pediatric patients. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:645–50. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000166764.99863.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fragen RJ, Shanks CA, Molteni A, Avram MJ. Effects of etomidate on hormonal responses to surgical stress. Anesthesiology. 1984;61:652–6. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198412000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayub M, Levell MJ. Inhibition of human adrenal steroidogenic enzymes in vitro by imidazole drugs including ketoconazole. J Steroid Biochem. 1989;32:515–24. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(89)90384-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lamberts SW, Bons EG, Bruining HA, de Jong FH. Differential effects of the imidazole derivatives etomidate, ketoconazole and miconazole and of metyrapone on the secretion of cortisol and its precursors by human adrenocortical cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;240:259–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagner RL, White PF, Kan PB, Rosenthal MH, Feldman D. Inhibition of adrenal steroidogenesis by the anesthetic etomidate. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:1415–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198405313102202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Absalom A, Pledger D, Kong A. Adrenocortical function in critically ill patients 24 h after a single dose of etomidate. Anaesthesia. 1999;54:861–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1999.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vinclair M, Broux C, Faure P, Brun J, Genty C, Jacquot C, Chabre O, Payen JF. Duration of adrenal inhibition following a single dose of etomidate in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2007;34:714–9. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0970-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zolle IM, Berger ML, Hammerschmidt F, Hahner S, Schirbel A, Peric-Simov B. New selective inhibitors of steroid 11beta-hydroxylation in the adrenal cortex. Synthesis and structure-activity relationship of potent etomidate analogues. J Med Chem. 2008;51:2244–53. doi: 10.1021/jm800012w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allolio B, Schulte HM, Kaulen D, Reincke M, Jaursch-Hancke C, Winkelmann W. Nonhypnotic low-dose etomidate for rapid correction of hypercortisolaemia in Cushing’s syndrome. Klin Wochenschr. 1988;66:361–4. doi: 10.1007/BF01735795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diago MC, Amado JA, Otero M, Lopez-Cordovilla JJ. Anti-adrenal action of a subanaesthetic dose of etomidate. Anaesthesia. 1988;43:644–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1988.tb04148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ledingham IM, Watt I. Influence of sedation on mortality in critically ill multiple trauma patients. Lancet. 1983;1:1270. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)92712-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bloomfield R, Noble DW. Etomidate and fatal outcome--even a single bolus dose may be detrimental for some patients. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:116–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson WL., Jr. Should we use etomidate as an induction agent for endotracheal intubation in patients with septic shock?: A critical appraisal. Chest. 2005;127:1031–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.3.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Annane D. ICU physicians should abandon the use of etomidate! Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:325–6. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hildreth AN, Mejia VA, Maxwell RA, Smith PW, Dart BW, Barker DE. Adrenal suppression following a single dose of etomidate for rapid sequence induction: A prospective randomized study. J Trauma. 2008;65:573–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31818255e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuthbertson BH, Sprung CL, Annane D, Chevret S, Garfield M, Goodman S, Laterre PF, Vincent JL, Freivogel K, Reinhart K, Singer M, Payen D, Weiss YG. The effects of etomidate on adrenal responsiveness and mortality in patients with septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:1868–76. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1603-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cotten JF, Husain SS, Forman SA, Miller KW, Kelly EW, Nguyen HH, Raines DE. Methoxycarbonyl-etomidate: A novel rapidly metabolized and ultra-short-acting etomidate analogue that does not produce prolonged adrenocortical suppression. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:240–9. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181ae63d1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Jong FH, Mallios C, Jansen C, Scheck PA, Lamberts SW. Etomidate suppresses adrenocortical function by inhibition of 11 beta-hydroxylation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984;59:1143–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem-59-6-1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott EE, White MA, He YA, Johnson EF, Stout CD, Halpert JR. Structure of mammalian cytochrome P450 2B4 complexed with 4-(4-chlorophenyl)imidazole at 1.9-A resolution: Insight into the range of P450 conformations and the coordination of redox partner binding. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27294–301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ouellet H, Podust LM, de Montellano PR. Mycobacterium tuberculosis CYP130: crystal structure, biophysical characterization, and interactions with antifungal azole drugs. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:5069–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708734200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seward HE, Roujeinikova A, McLean KJ, Munro AW, Leys D. Crystal structure of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis P450 CYP121-fluconazole complex reveals new azole drug-P450 binding mode. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39437–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607665200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roumen L, Sanders MP, Pieterse K, Hilbers PA, Plate R, Custers E, de Gooyer M, Smits JF, Beugels I, Emmen J, Ottenheijm HC, Leysen D, Hermans JJ. Construction of 3D models of the CYP11B family as a tool to predict ligand binding characteristics. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2007;21:455–71. doi: 10.1007/s10822-007-9128-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waud DR. On biological assays involving quantal responses. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1972;183:577–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yano JK, Denton TT, Cerny MA, Zhang X, Johnson EF, Cashman JR. Synthetic inhibitors of cytochrome P-450 2A6: Inhibitory activity, difference spectra, mechanism of inhibition, and protein cocrystallization. J Med Chem. 2006;49:6987–7001. doi: 10.1021/jm060519r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Locuson CW, Hutzler JM, Tracy TS. Visible spectra of type II cytochrome P450-drug complexes: Evidence that “incomplete” heme coordination is common. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35:614–22. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.012609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutzler JM, Melton RJ, Rumsey JM, Schnute ME, Locuson CW, Wienkers LC. Inhibition of cytochrome P450 3A4 by a pyrimidineimidazole: Evidence for complex heme interactions. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:1650–9. doi: 10.1021/tx060198m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fallo F, Pilon C, Barzon L, Pistorello M, Pagotto U, Altavilla G, Boscaro M, Sonino N. Effects of taxol on the human NCI-H295 adrenocortical carcinoma cell line. Endocr Res. 1996;22:709–15. doi: 10.1080/07435809609043766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fallo F, Pilon C, Barzon L, Pistorello M, Pagotto U, Altavilla G, Boscaro M, Sonino N. Paclitaxel is an effective antiproliferative agent on the human NCI-H295 adrenocortical carcinoma cell line. Chemotherapy. 1998;44:129–34. doi: 10.1159/000007104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fassnacht M, Hahner S, Beuschlein F, Klink A, Reincke M, Allolio B. New mechanisms of adrenostatic compounds in a human adrenocortical cancer cell line. Eur J Clin Invest. 2000;30(Suppl 3):76–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2000.0300s3076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Husain SS, Ziebell MR, Ruesch D, Hong F, Arevalo E, Kosterlitz JA, Olsen RW, Forman SA, Cohen JB, Miller KW. 2-(3-Methyl-3H-diaziren-3-yl)ethyl 1-(1-phenylethyl)-1H-imidazole-5-carboxylate: A derivative of the stereoselective general anesthetic etomidate for photolabeling ligand-gated ion channels. J Med Chem. 2003;46:1257–65. doi: 10.1021/jm020465v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rusch D, Zhong H, Forman SA. Gating allosterism at a single class of etomidate sites on alpha1beta2gamma2L GABA A receptors accounts for both direct activation and agonist modulation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20982–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400472200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siegwart R, Jurd R, Rudolph U. Molecular determinants for the action of general anesthetics at recombinant alpha(2)beta(3)gamma(2)gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptors. J Neurochem. 2002;80:140–8. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.