Abstract

A paucity of validated kinase targets in human multiple myeloma has delayed clinical deployment of kinase inhibitors in treatment strategies. We therefore conducted a kinome-wide small interfering RNA (siRNA) lethality study in myeloma tumor lines bearing common t(4;14), t(14;16), and t(11;14) translocations to identify critically vulnerable kinases in myeloma tumor cells without regard to preconceived mechanistic notions. Fifteen kinases were repeatedly vulnerable in myeloma cells, including AKT1, AK3L1, AURKA, AURKB, CDC2L1, CDK5R2, FES, FLT4, GAK, GRK6, HK1, PKN1, PLK1, SMG1, and TNK2. Whereas several kinases (PLK1, HK1) were equally vulnerable in epithelial cells, others and particularly G protein–coupled receptor kinase, GRK6, appeared selectively vulnerable in myeloma. GRK6 inhibition was lethal to 6 of 7 myeloma tumor lines but was tolerated in 7 of 7 human cell lines. GRK6 exhibits lymphoid-restricted expression, and from coimmunoprecipitation studies we demonstrate that expression in myeloma cells is regulated via direct association with the heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) chaperone. GRK6 silencing causes suppression of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) phosphorylation associated with reduction in MCL1 levels and phosphorylation, illustrating a potent mechanism for the cytotoxicity of GRK6 inhibition in multiple myeloma (MM) tumor cells. As mice that lack GRK6 are healthy, inhibition of GRK6 represents a uniquely targeted novel therapeutic strategy in human multiple myeloma.

Introduction

The role of kinases in the propagation of myeloma cells has been established by studies examining vascular endothelial-derived growth factor receptor (VEGFR) kinase,1 insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor, Janus kinase,2 AKT,3–6 protein kinase C,7,8 Cdk4/6,9 IκB kinase β,10 and fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3).11–14 Furthermore, overexpression of FGFR3 occurs in a subset of multiple myeloma tumors with t(4;14) translocation and mutants of this kinase are transforming in B cells.11,14,15 However, less than 5% of cellular kinases have previously been examined for vulnerability in myeloma and clinically proven targets have not yet been identified. We therefore report the generation of a kinome-wide map of critically vulnerable kinases in myeloma cells, to provide impetus for kinase targeting in this malignancy.

Methods

siRNA and shRNA

The human kinome siRNA library was purchased from QIAGEN. This set of prevalidated custom siRNA comprises duplexes verified to provide more than 70% knockdown of each target gene. For validation of myeloma survival kinases, we designed 2 additional custom siRNAs per kinase that were synthesized by QIAGEN. Lentiviral shRNA clones targeting kinases of interest and control lentiviruses expressing nonsilencing (NS) shRNA or green fluorescent protein (GFP) cDNA were from the Sigma Mission Library (Sigma-Aldrich). Lentiviruses were prepared by transfection of plasmid DNA into 293T cells16 and were titered in parallel using a Quantiter Lentiviral p24 Titer Kit (Cellbiolabs).

siRNA transfection optimization and assay development

Transfection conditions for human myeloma or epithelial cell lines were individually optimized using commercially available cationic lipids. The functional transfection efficiency was determined by comparing viability phenotype after transfecting (1) a universally lethal positive control siRNA against ubiquitin B (UBBs1) or (2) negative control siRNA, including a nonsilencing scrambled siRNA or an siRNA against GFP. For reverse transfection in high-throughput format, negative and positive control siRNAs were printed on 96-well and 384-well plates. The influences of cell and reagent concentrations, growth media, percentage fetal bovine serum, time since passage, and presence of vehicle were assessed. Viability was determined at 96 hours by CellTitre-Glo luminescence (Promega) or by methylthiazolyldiphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. The best reagent and transfection conditions were those that produced the least reduction in cell viability with negative controls and greatest reduction with lethal UBBs1 siRNA. Optimized transfection conditions were separately derived for KMS11, INA6, JJN3, A549, and 293 cells such that specific modulation of viability with control siRNA was more than 90% and nonspecific toxicity was less than 10%.

High-throughput kinome siRNA screening

A total of 1278 siRNAs targeting 639 individual human kinase genes were preprinted on 384-well plates alongside staggered negative and positive control siRNA. Primary kinome screening experiments were conducted in duplicate on separate occasions for both KMS11 and INA6 cells. For each experiment, plates preloaded with siRNA and frozen were thawed at room temperature and 20 μL/well-diluted Lipofectamine 2000 (KMS11; Invitrogen) or Dharmafect 3 (INA6; Dharmacon) solution was added. After 30 minutes, 1500 KMS11 or 1000 INA6 cells in 20 μL of medium were added to each well. Cell viability was determined at 96 hours by CellTiter-Glo luminescence assay read on a BMG Polarstar machine using excitation 544-nm/emission 590-nm filters.

Identification of survival kinases

For survival kinase analyses, B-score normalization was applied to primary screening luminescence values as previously described17–19 to eliminate plate-to-plate variability and well position effects.

Z-score normalization was used for secondary validation siRNA studies and was calculated as the difference in viability outcome between test siRNA and the mean of nonsilencing control siRNA, normalized to the distribution (standard deviation) of nonsilencing control siRNA replicates, as described.17 Our B- or Z-scores each therefore reflect both the magnitude of lethality of an siRNA and the level of confidence that the siRNA's activity differs from that of inactive siRNA, measured in standard deviations from the latter. To ensure accurate interpretation of high-throughput screening data, primary screening results were parsed for random outlier data points with more than 3-fold discrepancy between duplicate runs, and the outlying result was excluded if it was substantially inconsistent with paired replicate data. As a consequence, results of 12 or 22 wells from 3840 per screen were excluded for KMS11 or INA6, respectively, representing less than 0.5% of results.

Defining survival kinase

From primary screening, we defined survival kinases as kinases targeted by siRNA that decreased myeloma cell viability by more than 3 standard deviations from cells treated with inactive siRNA. As the B-score was normalized to the standard deviation of results the probability due to chance of an siRNA causing a decrease in viability readout with B-score less than −3 was approximately less than 0.15%. To exclude the possibility of siRNA with biologic off-target effects contributing to our observations, we conducted secondary validation studies using multiple siRNA per kinase and defined validated survival kinases as those kinases whose inhibition was lethal to myeloma cells with concordant results from 3 or 4 of 4 unique siRNAs targeting them; kinases lethal with only 2 of 4 siRNAs targeting them were considered weak survival kinases and less validated targets that may include false-positive screening hits.

Selectivity of survival kinases: siRNA transfection of JJN3, A549, and 293 cells

To assess the selectivity of myeloma survival kinase vulnerability, JJN3, A549, and 293 cells were tested with short-listed kinase siRNA. Experimental transfection conditions were as follows: JJN3 cells, 104/well, were transfected with 26nM siRNA using 0.6 μL/well RNAiMax (Invitrogen); A549 cells, 8 × 103/well, were transfected with 40nM siRNA using 0.8 μL/well Lipofectamine 2000; 293 cells, 8.5 × 103/well, were transfected with 30nM siRNA using 0.25 μL/well Lipofectamine 2000. Secondary siRNA experiments were performed in duplicate and viability was determined at 96 hours.13

Gene expression of survival kinases in human tissues and primary multiple myeloma tumors

Primary bone marrow samples from patients with multiple myeloma (MM), smoldering MM (SMM), or monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance (MGUS) were collected and processed for gene expression as described20; CEL files are deposited on the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO accession no. GSE 6477). All patient samples were obtained with Mayo Clinic institutional review board approval and patient consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Expression data from other human somatic tissues were obtained from the Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation, SymAtlas.21 Gene expression data were generated in all cases using Hg_U133A_2 microarrays (Affymetrix). Probe-set signal intensities were MAS5 transformed and flagged using Affymetrix Microarray Suite 5 (MAS5) present/absent/marginal detection calls. Data were analyzed using GeneSpring 7 (Agilent Technologies) software. To compare the expression of kinases in primary multiple myeloma samples versus other grouped human somatic tissues (excluding MGUS or SMM), 1-way Welch analysis of variance was performed (parametric ranking, with no assumption of equal variance) using Benjamini-Hochberg multiple testing correction (false discovery rate 0.05). In Figure 4, data are shown normalized per chip to the median signal of genes expressed within each sample (genes with present detection call or raw signal > 200).

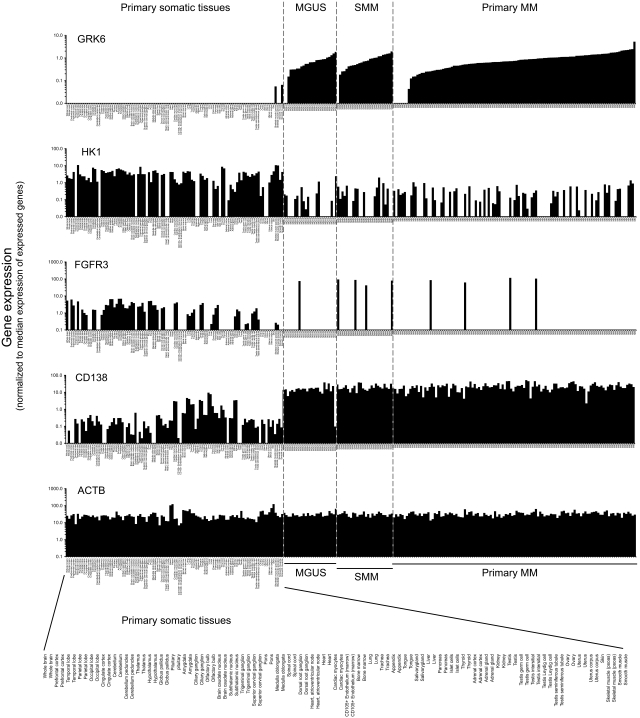

Figure 4.

Expression of selected myeloma survival kinases in primary multiple myeloma versus an atlas of nonhematopoietic human tissues. Histograms show the differential patterns of expression of myeloma survival kinases (GRK6, HK1, and FGFR3) and of control genes (CD138 and β-actin) in primary human somatic tissues (103 arrays), primary multiple myeloma tumor cells (115 arrays), and in early stage plasma cell disorders: monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significant (MGUS) and smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM; data from SymAtlas, Novartis Research Foundation and from Mayo Clinic; GEO accession no. GSE 6477). Array-based gene expression data were normalized per chip (sample) to the median signal intensity of expressed genes (genes with present detection call and/or MAS5 signal intensity > 200); a value of 1.0 thus represents the median expression intensity of genes whose expression can be reliably detected within each sample type.

Survival kinase pathway analysis

Kinase functional assignment was derived from National Cancer Institute David (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov)22 and the literature. To investigate the distribution of survival kinases identified in myeloma cells with respect to biologic pathways, we subjected validated survival kinases to network analysis (MetaCore; GeneGo Inc) using a shortest path algorithm, limited to 2 steps (edges) between nodes.

Immunoblotting

Cells were washed in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and disintegrated in cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology). Extracts were centrifuged, quantified by bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce), and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE; 10 μg/lane). Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride and immunoblotted with antibodies specific for AURKA (no. AF3295; R&D Systems), PKN1 (no. ab36745; Abcam), GRK6 (no. ab38291; Abcam), FLAG (M2; Sigma-Aldrich), heat shock protein 90 (HSP90; no. 4874; Cell Signaling Technology), phospho-AKT (Ser473; no. 9271; Cell Signaling Technology), phospho-p44/42 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase (extracellular signal-related kinase 1/2 [ERK1/2]; Thr202/Tyr204; no. 9101; Cell Signaling Technology), p44/42 MAPK kinase (no. 4695; Cell Signaling Technology), phospho-MAPK8 (also known as c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 [JNK]), (Thr183/Tyr185; no. 9255; Cell Signaling Technology), phospho–signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3; Tyr705; no. 9138; Cell Signaling Technology), STAT3 (sc-7179; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), α-tubulin, and β-actin (both from Cell Signaling Technology); signal was detected using Western Lighting Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (PerkinElmer).

GRK6-shRNA lentiviral experiments

Three lentiviruses (LVs) targeting GRK6 were screened to identify shRNA that optimally suppressed the kinase; immunoblotting of KMS11 lysates 48 hours after infection was used to gauge suppression of GRK6 relative to β-actin. Viral shRNA sequences were distinct from GRK6 siRNA sequences used in primary screening. Equal titers of NS-shRNA, GFP cDNA, and GRK6-shRNA virus were used to infect cells. LV clone no. 66, which optimally suppressed GRK6, was used for subsequent experiments. GRK6 silencing was verified by immunoblotting at 48 hours; the same cultures were examined for cellular infection by GFP expression and for induction of apoptosis by flow cytometry. Apoptosis was assessed using annexin V reagent and 7-amino-actinomycin D (BD Biosciences).

3xFLAG-tagged GRK6 cell lines

The GRK6 open reading frame was amplified from Open Biosystems clone 4053197 (accession BC009277, BC009277.2, BF128454, BF127497, BF128454.1, BF127497.1) to introduce 5′NotI and 3′EcoRV sites and was cloned into p3xFLAG-Myc-CMV-26 (catalog no. E6401; Sigma-Aldrich) to encode a reading frame with features: N-Met-3xFlag tag-NotI linker(Leu-Ala-Ala)-GRK6. The GRK6 stop codon was maintained to prevent expression of the C-terminal Myc tag. The construct was subcloned into a modified lentiviral pWPIS1 vector and an IRES-eGFP cassette was introduced to report insert expression. Several resulting clones of plasmid pWPIS1-EF1a-N-Met-3xFLAG-(NotI)-GRK6A-(STOP)-(BamH1)-IRES-eGFP were sequence verified and screened for their ability to produce lentivirus, driving high-level 3xFLAG-GRK6 expression. KMS11 and OPM1 cells were then infected with optimum clones (nos. 2 and 11) and FACS sorted on days 7 and 16 by GFP expression to derive stable cell lines producing 3xFLAG-GRK6 plus IRES-eGFP from integrated lentivirus.

GRK6 complex isolation from KMS11 or OPM1 stable lines

The protocol is based on a previously reported procedure.23 Approximately 109 cells (control and GRK6 stable cell lines) were harvested, washed, and immediately lysed on ice in solution containing Nonidet P-40 or Triton X-100 at 0.3% to 1%, 20mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid (pH 7.9), NaCl 150mM, 10mM KCl, 1mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, glycerol 10%, fresh phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride 1mM, and fresh protease inhibitors (Pierce; 100 μL per 10 mL). Samples were centrifuged to remove nuclei and precleared of nonspecific binding proteins by incubation for 1 hour at 4°C with normal mouse immunoglobulin and protein G–sepharose. The resulting supernatants were used as cytoplasmic extracts for anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation. M2-sepharose beads (Sigma-Aldrich) were used to purify 3xFLAG-GRK6 complexes. GRK6 binding proteins were eluted and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were visualized by Simply Blue Coomassie stain (Pierce) and specific bands were identified by nanoscale liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (nanoLC-ESI-MS/MS).

Small-molecule GRK6 inhibitor studies

To assess GRK6 as a pharmaceutical target in myeloma, we tested the cytotoxic activity of small-molecule inhibitor GF109203X (Sigma-Aldrich)24 against a spectrum of diverse human myeloma tumor lines and primary patient samples. Cell viability was determined at 72 hours by flow cytometry or by MTT (Sigma-Aldrich) assay, as described.13 Cytotoxicity of GF109203X in myeloma and nonmyeloma cells was compared at the highest tested concentration (20μM) by non-Gaussian nonparametric Mann-Whitney testing.

Results

Kinases that regulate multiple myeloma cell survival

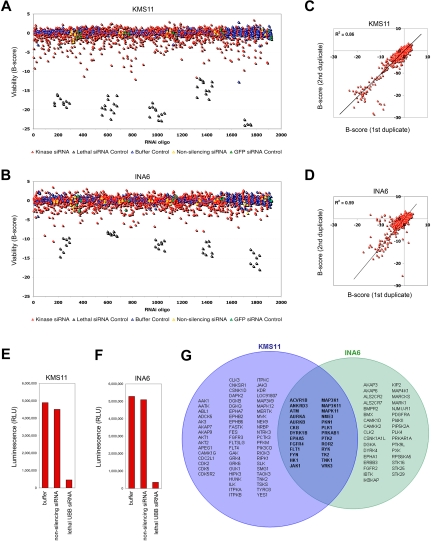

A high-throughput systematic RNA interference (RNAi) approach was adopted to identify kinases that regulate myeloma cell proliferation or survival. KMS11 and INA6 human multiple myeloma cells were transfected separately with synthetic short interfering RNAs (siRNA) targeting each of the 639 known and putative kinases. JJN3 myeloma cells were used in secondary validation screens. These tumor lines were used for their genetic heterogeneity and are representative of t(4;14) (KMS11), t(14;16) (KMS11 and JJN3), and t(11;14) (INA6) myeloma variants (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Primary screening was performed in duplicate using an 1800-oligo siRNA library in a single-siRNA-per-well format. siRNAs were transfected at low concentration (13nM) to minimize off-target effects using conditions that resulted in transfection of more than 95% cells and less than 5% background cytotoxicity. After 96 hours, viability was measured by adenosine triphosphate–dependent luminescence (Figure 1A-F). Kinases targeted by 1 or more siRNAs lethal or inhibitory to KMS11 or INA6 during primary screening were implicated as candidate survival kinases. Using a threshold B-score less than −3 for any single siRNA, representing a 3 standard deviation reduction in viability or proliferation, 88 kinases (14%) were identified as candidate survival kinases in KMS11 cells and 59 (9%) were identified in INA6 cells (Figure 1G), compared with a predicted rate due to chance of less than 3.5 kinases (0.5%) per tumor line. Our siRNA results were highly reproducible, with significant correlation between duplicate full-scale library assays, performed separately (R2 = 0.86 for KMS11; R2 = 0.58 for INA6; Figure 1C-D). However, as siRNA may cause silencing of more than 1 gene, the false discovery rate for candidate survival kinases implicated by a single siRNA is high. To eliminate false positives, candidate survival kinases were subjected to validation studies (see next section, “Secondary screening and validation of survival kinases”). Surprisingly, only 4% of kinases were implicated in the survival of both KMS11 and INA6 myeloma cells, reflecting the genetic heterogeneity of myeloma and the narrow spectrum of kinases on which the disease is universally dependent.

Figure 1.

Kinome-wide siRNA lethality screening in myeloma cells. Prevalidated siRNA directed against 639 human kinases and associated subunits were transfected into (A) KMS11 and (B) IL6-dependent INA6 human multiple myeloma cells in high-throughput screening experiments using 2 siRNAs per target tested in a single-siRNA-per-well format. Cell viability was determined at 96 hours by adenosine triphosphate concentration. siRNA-induced changes in viability are shown, measured in units of standard deviation (B-score) from the median of noninhibitory siRNA, plotted in the order in which siRNAs were screened. Cells treated with transfection reagent alone, GFP siRNA, or 1 of 2 unique nonsilencing (NS) scrambled siRNAs represent negative controls. Positive controls for transfection efficiency were included at regular intervals throughout the screen and are cells treated with an siRNA targeting ubiquitin B. (C-D) Results of kinome siRNA studies in myeloma cells were highly reproducible, with significant correlation between duplicate studies performed at separate times on KMS11 and on INA6, respectively. (E-F) Operative transfection efficiency during primary kinome screening studies in (E) KMS11 and (F) INA6, measured by modulation of viability by control siRNA. The median result for each condition is shown. (G) Kinases in KMS11 and INA6 myeloma cells associated with at least 1 lethal siRNA (with B-score < −3) during kinome-scale screening; top-ranked kinases were forwarded to validation studies.

Secondary screening and validation of survival kinases

To validate genuine myeloma survival kinases, and to exclude kinases implicated by off-target siRNA effects, each short-listed kinase was tested with 4 unique siRNA: 2 in primary screening and 2 in secondary testing (Figure 2A). Importantly, of candidate survival kinases advanced to secondary screening, 15 were repeatedly cytotoxic with 3 or 4 of 4 independent siRNAs directed against them, verifying their identification by on-target siRNA effects. Their discovery compares with a predicted rate due to chance of less than 1 kinase. Those kinases with concordant results from 3 or 4 of 4 lethal siRNAs were defined as myeloma survival kinases and are listed in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Validation of myeloma survival kinases. (A) Top-ranked kinases targeted by lethal siRNA during primary high-throughput screens were tested in KMS11 cells using 4 unique siRNAs per kinase, assayed individually in separate wells, to verify survival kinase identification and to exclude kinases falsely identified during primary screening by chance or by off-target siRNA effects. As not all siRNAs efficiently silence their target, only the top 3 of 4 siRNAs tested are shown. The effects on viability of siRNAs are shown in arbitrary relative units, with UBB siRNA inducing approximately 100% cell death. To exclude false positives, only kinases whose targeting yielded concordant lethal results from ≥ 3 of 4 unique siRNAs were considered validated survival kinases. For validated survival kinases, the median viability loss induced by all siRNAs tested is shown as a bar. (B) XY plot of kinase gene mRNA expression in KMS11 and INA6 versus kinase siRNA lethality during primary kinome screening. Kinase mRNA levels were determined by Affymetrix (U133_2+ chip) expression profiling and represent the mean signal intensity (MAS5) of all probe sets per gene. Validated survival kinases are labeled.

Table 1.

Validated myeloma survival kinases: functional categories

| GenBank accession no. | Symbol | Description | Vulnerability, BZ-score |

Lethal with 2+ unique siRNA in these myeloma lines | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KMS11 | INA6 | JJN3 | ||||

| Cell-cycle regulation | ||||||

| NM_005030 | PLK1 | Pololike kinase 1 | −11.5 | −7.7 | −6.8 | KMS11, INA6, JJN3 |

| NM_001787 | CDC2L1 | Cell division cycle 2-like 1 (PITSLRE proteins) | −9.3 | −2.9 | −3.0 | KMS11, JJN3 |

| NM_004217 | AURKB | Aurora kinase B | −6.9 | −3.8 | −6.0 | KMS11, JJN3 |

| NM_003600 | AURKA | Aurora kinase A (serine/threonine kinase 6) | −6.3 | −3.3 | −4.3 | KMS11, INA6, JJN3 |

| NM_005255 | GAK | Cyclin G associated kinase | −4.6 | 0.7 | −3.8 | KMS11 |

| NM_003936 | CDK5R2 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 5, regulatory subunit 2 (p39) | −4.2 | −0.5 | −3.5 | KMS11, JJN3 |

| Proto-oncogenes: proliferation or survival | ||||||

| NM_002005 | FES | Feline sarcoma oncogene | −9.1 | −0.8 | −3.8 | KMS11, JJN3 |

| NM_005163 | AKT1 | v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1 | −6.9 | 0.2 | −4.9 | KMS11, JJN3 |

| VEGF signaling | ||||||

| NM_182925 | FLT4 | fms-related tyrosine kinase 4 (VEGFR3) | −6.2 | −2.5 | −5.3 | KMS11, JJN3 |

| G-protein receptor signaling | ||||||

| NM_002082 | GRK6 | G protein–coupled receptor kinase 6 | −6.4 | 0.0 | −3.1 | KMS11 |

| JNK/NF-κB activation | ||||||

| NM_002741 | PKN1 | Protein kinase N1 (protein kinase C-like 1) | −8.7 | −5.9 | −5.6 | KMS11, INA6, JJN3 |

| RNA/DNA surveillance (nonsense-mediated decay) | ||||||

| NM_014006 | SMG1 | PI-3-kinase-related kinase SMG-1 (LIP) | −11.2 | −2.7 | −5.2 | KMS11, JJN3 |

| Metabolic regulation | ||||||

| NM_033498 | HK1 | Hexokinase 1 | −9.9 | −6.7 | −5.6 | KMS11, INA6, JJN3 |

| NM_013410 | AK3L1 | Adenylate kinase 3 like 1 | −3.6 | 0.2 | −5.5 | KMS11, JJN3 |

| Novel | ||||||

| NM_005781 | TNK2 | Activated Cdc42-associated kinase 1 (tyrosine kinase, nonreceptor, 2) | −7.8 | −1.6 | −2.6 | KMS11 |

A further 25 kinases were inhibitory to KMS11 or INA6 with 2 independent siRNAs but were either insufficiently lethal to be advanced to secondary testing or yielded inconsistent results with the additional 2 siRNAs directed against them. These kinases therefore represent survival kinases on which myeloma cells are only partially dependent and/or less validated targets that may include false-positive screening hits. These partially validated myeloma survival kinases are listed in supplemental Table 2 and are not discussed further.

Our next quality control was a comparison of kinase siRNA lethality with kinase gene expression in KMS11 and INA6 cells to detect nonexpressed kinases implausibly identified as survival targets, and to look for bias against siRNA-based identification of vulnerability among highly expressed kinases (Figure 2B). All but 1 of the survival kinases identified with 2 or more concordant siRNAs in KMS11 were expressed (MAS5 signal > 150) in that tumor line supporting a credible survival role: expression of GRK4 was unsubstantiated and this kinase was not subsequently included in our validated survival kinase set. Similarly, all kinases identified with 2 of 2 siRNAs in INA6 and validated with 3 or 4 of 4 in KMS11 were detectably expressed in both INA6 and KMS11 cells. Thus, the essential myeloma survival kinases listed in Table 1 (and in supplemental Table 2) were each verified by concordant results from multiple lethal siRNAs and show nonrandom selection favoring expressed genes. No bias in the ability to detect highly expressed vulnerable kinases was evident.

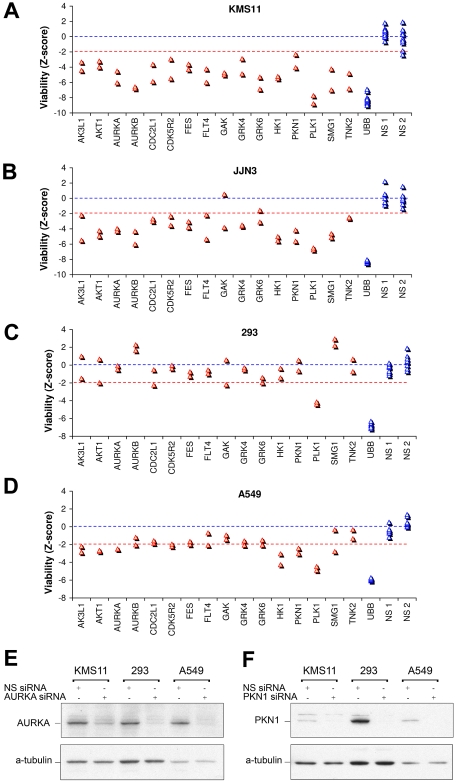

To assess the extent to which our list of myeloma survival kinases may be vulnerable in, and portable to, other myeloma cells, we next prospectively tested the effect of silencing these in a third myeloma tumor line, JJN3 (Figure 3). Conspicuously, 90% of vulnerable kinases, identified from screening of KMS11 and INA6, were also vulnerable in JJN3 (Figure 3A-B). The lethality of kinase siRNAs in KMS11 and JJN3 cells was strikingly correlated (R2 = 0.73, supplemental Figure 1). Taking account of all 3 myeloma lines tested, the most vulnerable myeloma kinases include PLK1, HK1, TNK2, AURKB, AURKA, GRK6, PKN1, SMG1, GAK, and AKT1.

Figure 3.

Selective vulnerability of myeloma survival kinases. (A-D) Effect on viability of siRNA directed against top-ranked myeloma survival kinases in (A) KMS11 and (B) JJN3 myeloma cells, and in (C) 293 embryonic kidney and (D) A549 lung carcinoma cells. Cells were transfected with 2 unique siRNAs per kinase in separate wells, using conditions optimized for each cell line each associated with > 90% transfection efficiency. Viability was assessed at 96 hours and is plotted in units of standard deviations from control siRNA. (E-F) Western blot analysis of kinase knockdown after siRNA targeting of (E) AURKA and (F) PKN1, confirming equivalent or greater transfection and protein knockdown in 293 and A549 cells, compared with KMS11 myeloma cells. Cells were transfected using the same conditions as panels A through D optimized for each line, and lysates were prepared at 48 hours; 10 μg of total protein was loaded per lane.

Vulnerable kinase networks in myeloma cells

We next subjected our sets of validated survival kinases to network analysis using a shortest path algorithm (MetaCore). Clustering of vulnerable kinases within GeneGo processes and an interaction-limited network (supplemental Figures 2-3) implicates VEGF, FGF, and interleukin-6 (IL6)/insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor signaling, acting via AKT1, c-Abl, and Janus kinase 1, as critical nonredundant pathways essential for KMS11 or INA6 cell proliferation or survival. KMS11 bears a t(4;14)(p16;q32) translocation that causes constitutive FGFR3 overexpression11; and FGFR3, VEGF, and AKT1 have each previously been identified in myelomagenesis,3,4,11,14,25 providing biologic validation of our high-throughput identification of survival kinases. More than half of the validated survival kinases potentially interacts within 2 steps of one another. The shortest-path network for these vulnerable kinases converges to influence cell-cycle checkpoints, particularly mitotic spindle formation via AURKA, AURKB, and PLK1 (supplemental Figure 2). Consistent with this model, down-regulation of distal effector kinases in these pathways has greater lethal effect than down-regulation of upstream kinases (Table 1 and supplemental Table 2).

Myeloma selectivity of survival kinases

To assess the specificity of myeloma kinome vulnerabilities, the effects of targeting these kinases in epithelial A549 (lung carcinoma) and 293 (embryonic kidney) cells was next determined (Figure 3C-D) and contrasted with the lethality observed in myeloma cells. Adequate transfection of these cells was first verified by control siRNA targeting UBB, which was lethal (Figure 3C-D). In addition, silencing of 2 representative kinases, AURKA and PKN1, was confirmed by immunoblot to be at least as effective in 293 and A549 cells as in KMS11 myeloma cells, confirming comparable transfection efficiencies (Figure 3E-F). Importantly, siRNA directed against most myeloma survival kinases had considerably less effect on the viability of 293 or A549 epithelial cells than on myeloma cells (Figure 3A-D), despite efficient transfection of 293 and A549. However, PLK1 was universally vulnerable in all 5 cell lines tested and HK1, AK3L1, PKN1, AKT, and AURKA were each vulnerable with concordant siRNA in A549 carcinoma cells, although appeared nonessential in 293 cells. The sensitivity of A549 carcinoma cells to AURKA silencing was less than that of KMS11, INA6, or JJN3 myeloma cells. Minimal effect on A549 or 293 viability was observed with siRNA against myeloma survival kinases TNK2, GRK6, FLT4, FES, or even AURKB, indicating that these kinases are not universally vulnerable in all cells.

To further assess myeloma survival kinases for myeloma-selective vulnerability, we next investigated their expression, across a broad range of human somatic tissues (n = 101 samples, representing 51 tissues) and in primary patient MGUS and myeloma tumor (n = 101) cells (supplemental Figure 4) to determine whether any are selectively expressed in plasma cells or myeloma, and absent from other tissues. Approximately 50% of kinases are expressed at statistically different levels in primary myeloma cells versus somatic tissues (P < .05). Of myeloma survival kinases, GRK6, PKN1, CDC2L1, and FGFR3 show selective expression in primary myeloma tumors, compared with nonlymphoid human somatic tissues, whereas HK1 expression is in contrast 10- to 100-fold lower in primary myeloma than in somatic tissues. Dysregulation of FGFR3 in approximately 15% of myeloma tumors by t(4;14) translocation has previously been described. The differential expression of GRK6 in lymphoid tissues in general and myeloma in particular is striking. The intensity of expression of GRK6 in primary myeloma differs overtly from that in primary somatic tissues (P < .001; Figure 4). Moreover, present/absent detection calls (generated by statistical comparison of paired matched-mismatched probes) for GRK6 indicate that GRK6 mRNA is undetectable by microarray in all nonhematopoietic primary somatic tissues tested, whereas in contrast it is ubiquitously detected in plasma cells and lymphoid tissues.

GRK6 is a novel kinase target in myeloma

As demonstrated, GRK6 inhibition is selectively lethal to KMS11, INA6, and JJN3 myeloma cells and has minimal effect on 293 or A549 epithelial cells. Furthermore, GRK6 is ubiquitously expressed in lymphoid tissues and myeloma, but by comparison appears absent or only weakly expressed in most primary human somatic tissues. Although not detected by gene expression array in nonlymphoid primary tissues, we find that GRK6 is expressed at high levels in a colorectal adenocarcinoma, and potentially activating missense mutations of GRK6 have been described in gastric carcinoma26 and breast carcinoma27 samples. Although GRK6 expression in primary somatic tissues has been reported,28,29 this is at scarcely detectable levels30 and may reflect the presence of contaminating blood or lymphoid cells. Significantly, the invulnerability of somatic tissues to GRK6 inactivation is strongly substantiated by the murine GRK6−/− phenotype, which is healthy and viable,31 implicating GRK6 as a tolerable, druggable target in vivo. In contrast, other myeloma survival kinases have morbid null mutation phenotypes (supplemental Table 3).

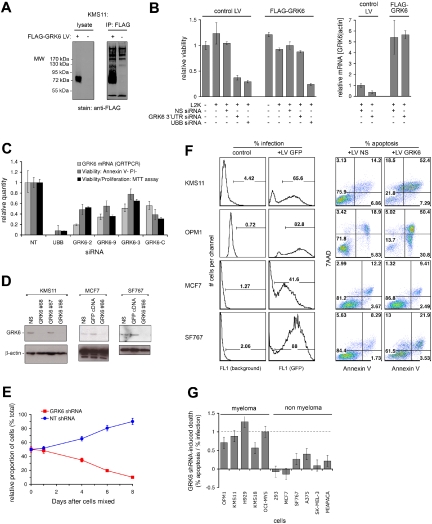

Therefore, GRK6 is a promising therapeutic target in multiple myeloma and perhaps in other lymphoid tumors. To examine this possibility further, we first sought to rescue myeloma cells from GRK6-targeted siRNA, using a resistant GRK6 mRNA, to verify that GRK6 siRNA-induced lethality occurs via on-target GRK6 suppression and not via off-target effects. A KMS11-derived myeloma tumor line stably overexpressing lentivirus-integrated FLAG-tagged GRK6 was generated, and FLAG-GRK6 expression was assessed (Figure 5A). FLAG-GRK6–expressing cells, and control KMS11 infected with lentiviral backbone, were then transfected in parallel with a GRK6 3′ untranslated region (UTR) siRNA that targets native GRK6 but that fails to target FLAG-GRK6 (as this lacks endogenous 3′UTR sequence; Figure 5B). Suppression of native GRK6, but not FLAG-GRK6, by the 3′UTR siRNA was confirmed by quantitative reverse-transcription–polymerase chain reaction (QRT-PCR; Figure 5B right panel). Persistent expression of FLAG-GRK6 rescued KMS11 cells from the lethal effect of the 3′UTR siRNA (Figure 5B left panel), but not from control siRNA targeting UBB, validating the identification of GRK6 as an essential myeloma survival kinase. This conclusion was further corroborated by concordant results using 4 different exon-based siRNAs demonstrating GRK6 silencing (by QRT-PCR) with resulting inhibition of KMS11 proliferation and viability (by flow cytometry and MTT assay; Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

GRK6 kinase silencing induces selective apoptosis of myeloma cells. (A) KMS11 myeloma cells were infected with lentivirus driving the expression of 3xFLAG-tagged GRK6 (+), or with control lentivirus (−), and were assessed by anti-FLAG immunoblot (left panel) and immunoprecipitation (right panel), verifying abundant tagged GRK6 protein production. (B) KMS11 cells stably infected with 3xFLAG-GRK6 expressing LV, or with control LV, were treated with Lipofectamine 2000 (L2K) transfection reagent and control or GRK6 3′UTR siRNA. GRK6 3′UTR siRNA induced native GRK6 mRNA suppression in control cells, but did not suppress 3xFLAG-GRK6 (which lacks GRK6 3′ UTR sequence), as shown by QRT-PCR at 48 hours (right panel). The effect of GRK6 3′ siRNA on KMS11 viability at 96 hours was assessed in parallel by MTT assay (left panel). Ectopic 3xFLAG-GRK6 rescues KMS11 from GRK6 3′UTR siRNA-induced lethality, verifying that the siRNA's lethality is due to on-target GRK6 silencing. Both KMS11 lentiviral lines were tested with NS and UBB siRNA, revealing equivalent transfection efficiency and minimal L2K toxicity. (C) The lethality of GRK6 silencing in KMS11 myeloma cells was further verified by 4 GRK6 siRNAs (GRK6-2, -9, -3, -C) that target GRK6 exons: after transfection of KMS11, GRK6 mRNA knockdown was assessed by QRT-PCR at 48 hours and viability was assessed by annexin V + propidium iodide binding and by MTT assay (at 96 hours). Cellular inhibition was due largely to apoptosis. (D) Lentiviruses nos. 66 to 68 expressing distinct short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting GRK6 were screened for induction of GRK6 knockdown in KMS11 by immunoblot at 48 hours. LV no. 66 and no. 68 both induced GRK6 knockdown in contrast to no. 67 and control LV expressing nonsilencing (NS) shRNA. LV no. 66 induced similar suppression of GRK6 in MCF7 and SF767 cells. (E) OPM1 myeloma cells infected with GFP-expressing LV no. 66 were mixed 1:1 with OPM1 cells infected with control LV. Cells in which GRK6 was targeted by shRNA no. 66 were progressively eliminated from culture, as determined by serial flow cytometry for the GFP marker, despite the presence of healthy control OPM1, which became enriched. (F) Comparison of the effect of GRK6-shRNA no. 66 on the viability of myeloma (KMS11 and OPM1) and nonmyeloma (MCF7 and SF767) cell lines. Cells were infected in parallel with equal titer LV producing NS-shRNA, GRK6-shRNA no. 66, or GFP cDNA; percentage cellular infection was determined by GFP expression. Specific apoptosis induction by GRK6 silencing at 96 hours was determined by annexin V and 7-amino-actinomycin D binding, comparing control LV (producing NS-shRNA) with LV GRK6-shRNA no. 66. (G) The effect of GRK6 inhibition on cellular viability is summarized for a spectrum of human myeloma and nonmyeloma cells. Results were obtained as shown in panel F and are plotted as the GRK6-shRNA attributable apoptosis normalized to the percentage infection obtained with each cell line. Error bars are calculated from 5% absolute error in assessments of infection and apoptosis.

We next sought to broaden our understanding of cellular vulnerability to GRK6 inhibition. To achieve GRK6 silencing in a broader range of cell types, and for longer duration, lentivirus-delivered shRNAs were used. Several lentiviruses producing shRNA targeting GRK6 were screened for induction of GRK6 silencing in several cell lines; of these, lentivirus GRK6-66 (Figure 5D) was the most efficient and was used for subsequent studies. Lentivirus GRK6-66 was engineered to express GFP and was then used to assess the growth kinetics of GRK6-silenced myeloma cells, cultured alongside control cells similarly infected with lentivirus backbone (Figure 5E). OPM1 myeloma cells infected with lentivirus GRK6-66 expressing GRK6 shRNA were mixed 1:1 with OPM1 cells infected with a backbone lentivirus lacking GFP and expressing a nonsilencing (NS) shRNA. Serial monitoring of this mixed culture for GFP expression revealed progressive selective loss of GRK6 silenced cells, despite the presence of healthy bystander cells, indicating that GRK6 silencing is directly inhibitory to myeloma cells, even if simple paracrine factors and cell-cell contact interactions are maintained.

The breadth of susceptibility of myeloma and human epithelial tumor lines to GRK6 inhibition was examined next. Using lentivirus GRK6-66, we induced GRK6 knockdown in a spectrum of 5 human myeloma and 6 epithelial tumor lines (Figure 5F and supplemental Figures 5-6). Conspicuously, lentiviral GRK6 shRNA induced extensive apoptosis in a variety of diverse multiple myeloma cell lines. In contrast, a control lentivirus delivering nonsilencing shRNA was nonlethal. Notably, GRK6 silencing in 3 myeloma tumor lines induced apoptosis in 1:1 proportion with cellular infection by lentivirus (Figure 5G), demonstrating extreme vulnerability of these cells to GRK6 inhibition, whereas in 2 other myeloma lines, GRK6 silencing caused more than 50% apoptosis within 96 hours. Instead, in epithelial cells, lentiviral infection and GRK6 shRNA were comparatively nontoxic, with median cytotoxicity 10% (± 15%) of infected cells. Thus, GRK6 inhibition is broadly lethal to myeloma tumor cells but appears tolerated in human epithelial cells, as in mice.

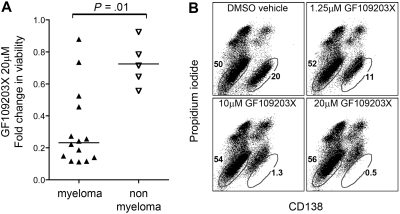

To further test this hypothesis, we next examined a semiselective pharmaceutical inhibitor of GRK6, GF109203X, for activity against a heterogeneous panel of myeloma and epithelial tumor lines as well as primary patient samples. GF109203X is an inhibitor of both protein kinase C and of GRK6 that causes near total inhibition of these kinases in vitro at distinct concentrations of 0.1μM and 1 to 10μM, respectively.24 Notably, GF109203X was substantially cytotoxic to 10 of 14 myeloma tumor lines and to myeloma cells from patients at concentrations most consistent with GRK6 inhibition (5-20μM), and was selectively more cytotoxic to myeloma tumor cells than to nonmyeloma cell lines (P = .01; Figure 6 and supplemental Figure 7), highlighting the potential of GRK6 as a pharmaceutical target for selective therapeutic intervention in myeloma.

Figure 6.

Cytotoxic effects of GF109203X, a dual inhibitor of protein kinase C (IC50, ∼ 0.1μM) and of GRK6 (IC50, ∼ 1-10μM), on myeloma cells versus nonmyeloma cells. (A) Cytotoxicity of 20μM GFX109203X at 72 hours is summarized for a spectrum of human myeloma and nonmyeloma cells, with statistical comparison by Mann-Whitney test. (B) An illustrative example of selective cytotoxic effect of GF109203X versus primary myeloma cells in mixed culture. Primary bone marrow cells from myeloma patients were treated in culture with 1.25 to 20μM GF109203X, or with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) vehicle control. After 72 hours, samples were stained with CD138–fluorescein isothiocyanate to identify myeloma cells (bottom right population) versus other marrow cells (bottom left population) and propidium iodide to distinguish late-stage apoptotic cells. At high concentrations (reflective of GRK6 rather than protein kinase C effect), GF109203X induced selective cytotoxicity that was confined to the tumor cell population, evidenced by CD138 shedding and propidium iodide uptake.

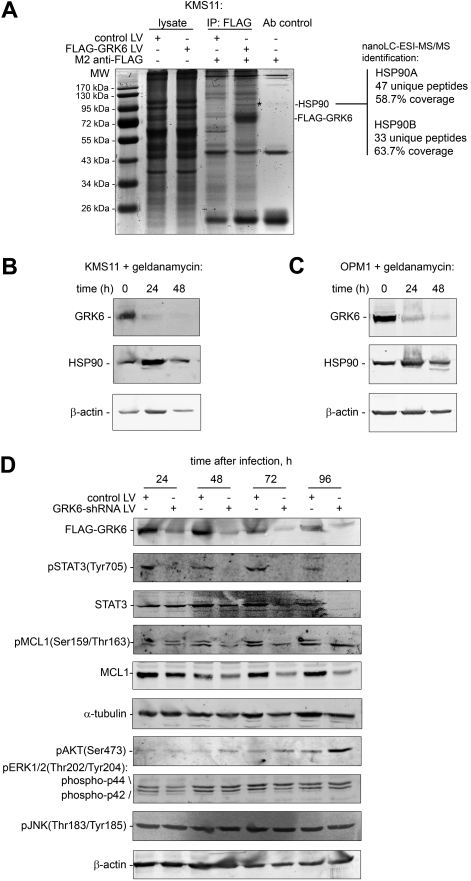

GRK6 is regulated by HSP90 and promotes STAT3 phosphorylation and MCL1 expression in myeloma cells

Despite strong evidence for GRK6's influence on myeloma cell survival, the mechanistic basis of this effect was uncertain. Therefore, to clarify the molecular role of GRK6 in myeloma, we next attempted to define GRK6 binding protein(s) in myeloma cells. GRK6-containing protein complexes were isolated by affinity purification from human KMS11 cells, engineered to stably express a 3xFLAG-tagged version of GRK6, and then separated by SDS-PAGE (Figure 7A). A 90-kDa GRK6 binding protein was visualized by Coomassie staining and was subsequently identified as heat shock protein 90 (both HSP90A and HSP90B) by nanoscale liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (nanoLC-ESI-MS/MS).

Figure 7.

GRK6 binds to and is regulated by the chaperone HSP90 in human myeloma cells and is required for phospho-STAT3 pathway signaling. (A) 3xFlag-tagged GRK6 protein complexes were affinity purified from 108 KMS11 myeloma cells using M2 antibody and separated by SDS-PAGE. A single GRK6 copurified protein (*) was detected by Coomassie staining, migrating at 90 kDa, and was subsequently identified by nanoLC-ESI-MS/MS as HSP90A/B. Additional immunoprecipitation (IP) Coomassie staining bands reflect M2 antibody fragments and “sticky” lysate proteins retained nonspecifically by sepharose. The identity of isolated 3xFLAG-GRK6 was confirmed by nanoLC-ESI-MS/MS. (B-C) HSP90 potently and rapidly (< 24 hours) regulates GRK6 protein levels in KMS11 (B) and OPM1 (C) myeloma cells. Both myeloma tumor lines were treated with the HSP90 inhibitor, geldanamycin, 1μM, for the specified times, and were then assayed for ensuing effects on GRK6 protein expression by immunoblot. (D) To assess the effect and kinetics of GRK6 inhibition on the activity of myeloma survival pathways, FLAG-GRK6–expressing OPM1 cells were infected with control lentivirus expressing nontargeting shRNA, or with lentivirus expressing GRK6 shRNA, and the phospho-activation status of key intracellular signaling mediators AKT, MAPK p42 and p44 (ERK1/2), JNK, and STAT3 was determined by immunoassay sequentially from 24 to 96 hours after viral shRNA infection. MCL1 phosphorylation and levels were examined in parallel.

Binding of HSP90 to a related kinase, GRK2, has previously been reported in HL60 cells32; and in that setting HSP90 posttranslationally regulates GRK2 activity.32 Suggestively, inhibitors of HSP90 cause growth arrest and apoptosis of myeloma cells,33,34 and this might in part be due to effects on GRK6 expression. To determine whether HSP90 influences GRK6 expression in myeloma tumor cells, we next treated 3xFLAG-GRK6-expressing KMS11 and OPM1 cells with a HSP90 inhibitor (geldanamycin), and then assayed for changes in GRK6 protein levels using an anti-FLAG antibody. HSP90 inhibition resulted in a rapid (< 24 hours) and potent decline in GRK6 levels that preceded cell death by several days (Figure 7B-C). Therefore, HSP90 regulates GRK6 expression in myeloma and an early consequence of HSP90 inhibition is GRK6 suppression.

To further define the role of GRK6 in myeloma, we examined the effect of silencing this kinase on the activity of key signaling members of major myeloma survival pathways (Figure 7D). OPM1 cells were infected with lentivirus expressing either GRK6 shRNA, or a nontargeting shRNA, and the phospho-activation status of AKT, MAPK (ERK1/2), JNK, and STAT3 was determined 24 to 96 hours after virus exposure by immunoblotting. Strikingly, whereas GRK6 knockdown had little or no effect on AKT, JNK, or MAPK (ERK1/2) phosphorylation, particularly within the first 72 hours, GRK6 inhibition caused rapid (< 24 hours) and comprehensive loss of STAT3 tyrosine phosphorylation, conspicuously in step with GRK6 silencing. Phosphorylation of STAT3 at Tyr705 regulates its dimerization, nuclear translocation, and DNA binding.35 Significantly, STAT3 is an oncogene36,37 that mediates many effects of IL6 on myeloma cells38 and is expressed in an activated form in most primary myeloma tumors,39 and in other major human cancers.37 STAT3 pathway inhibition in myeloma causes both cellular apoptosis and sensitization to chemotherapeutics,37,40,41 at least in part because STAT3 triggers up-regulation of Bcl-2 family protein Mcl-1,42 which exerts a pivotal survival role.43 Therefore, to test the hypothesis that GRK6 influences downstream MCL1 expression via STAT3, we examined the time course of MCL1 expression in cells exposed to GRK6 shRNA LV (Figure 7D). Importantly, GRK6 inhibition causes early suppression of STAT3 phosphorylation that is associated with early and sustained reduction in total MCL1 protein levels (within 24 hours), and late loss of MCL1 phosphorylation (at 72 hours and beyond), providing a potent mechanism for the cytotoxicity of GRK6 inhibition in myeloma tumor cells.

Discussion

Here, we present for the first time a “vulnerability” snapshot of the kinome in human multiple myeloma. Approximately half of the vulnerabilities identified concentrate within biologically relevant pathways. However, novel survival kinases with unknown function are also identified.

From our results, up to 15% of kinases promote myeloma cell survival. As expected, known survival kinase AKT1 was identified in our study as were nonredundant metaphase regulators PLK1, AURKA, AURKB, and CDC2L1, and nonredundant metabolic kinases HK1 and AK3L1. However, from a therapeutics perspective, such cell cycle–related or metabolic kinases are likely to be vulnerable in other cell types and their inhibition may be associated with target-related toxicity in vivo, limiting “druggability” in patients.

To address the selectivity of myeloma kinome vulnerabilities, we pursued 3 avenues: first, we functionally examined myeloma survival kinases for vulnerability in epithelial cells; second, we looked for selective expression of vulnerable kinases in primary myeloma versus other tissues; and third, we examined previously reported null mutation phenotypes. From this experimental and informatics approach, we identified GRK6 as an effective and selective target for kinase inhibitor therapy in multiple myeloma.

Importantly, GRK6 is ubiquitously expressed in primary myeloma tumors, is lethal to myeloma cells on silencing, and can be silenced in nonlymphoid human cells and in mice, without toxicity. GRK6 is highly expressed in myeloma cells via the chaperone HSP90, on which it is dependent, and GRK6 loss thus represents 1 potential mediator of HSP90 inhibitor effects. Significantly, GRK6 expression is required to maintain the activity of 2 key regulators of myeloma cell survival: STAT3 and MCL1, likely via phosphorylation of an unidentified upstream G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR). The classical example of STAT3 activation is via the interleukin/gp130 receptor, which is activated by IL6, however GPCR can also activate STAT3, via G protein subunits and small GTPases,44–48 and regulation of this may represent the principal activity of GRK6 in myeloma. From the literature, GRK6 is known to target various GPCRs potentially relevant in myeloma, including EDNRB49 and CXCR4.50

One limitation of RNAi studies is the potential for off-target effects. To counter this, we rigorously validated each result using multiple independent siRNAs per target and extensively tested control nonsilencing RNAi alongside kinase-specific oligos. For GRK6, for example, we observed myeloma cell lethality with 6 different siRNAs or shRNAs and observed nonlethality in epithelial cells with 3 of the same oligos; we additionally rescued cells from GRK6 siRNA lethality by expression of a 3′UTR siRNA-resistant GRK6 cDNA.

A second limitation of siRNA studies is the difficulty of achieving gene silencing in primary cells. Conduct of this study using primary patient sample studies proved infeasible, despite considerable effort; therefore to maximize the relevance of our results to primary myeloma, we used heterogeneous tumor lines representative of several major genetic subtypes of myeloma in developing our results. We then used gene expression data from primary tumors to verify that kinases with phenotypic effects in myeloma cell lines are broadly expressed in primary myeloma cells from patients. A small-molecule inhibitor was used to verify the cytotoxic effect of GRK6 targeting in primary myeloma cells.

A final limitation of this work is the inability to confirm that all kinases were adequately silenced; false-negative results are possible. Therefore absence of a kinase from our results should not necessarily imply absence of function in myeloma.

Overall, this study provides a kinome-scale view of the role of individual kinases in myeloma tumor cell survival. Detailed elaboration of the mechanisms by which survival kinases such as GRK6 influence myeloma cell fate will enhance the understanding of oncogenic signaling in this disease. Furthermore, the molecular vulnerabilities identified here are potentially important targets for the development of kinase inhibitors for the treatment of multiple myeloma.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Mayo Clinic (A.K.S.), National Institutes of Health grant number RO1CA129009-03, Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation (MMRF) fellowship (R.E.T.), MMRF senior research grant (A.K.S.), and Multiple Myeloma Research Consortium Genomics Initiative (D.A., L.M.P., S.M.).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: R.E.T. and A.K.S. designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; Y.X.Z., J.S., H.Y., C.X.S., G.B., and E.B. performed research; Q.Q. analyzed the data; D.A., R.F., P.L.B., and S.M. designed the research; and L.M.P. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Rodger E. Tiedemann, Mayo Clinic Arizona, 13400 E Shea Blvd, MCS_03, Scottsdale, AZ 85259; e-mail: tiedemann.rodger@mayo.edu.

References

- 1.Kovacs MJ, Reece DE, Marcellus D, et al. A phase II study of ZD6474 (Zactima, a selective inhibitor of VEGFR and EGFR tyrosine kinase in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma–NCIC CTG IND. 145. Invest New Drugs. 2006;24(6):529–535. doi: 10.1007/s10637-006-9022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pedranzini L, Dechow T, Berishaj M, et al. Pyridone 6, a pan-janus-activated kinase inhibitor, induces growth inhibition of multiple myeloma cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66(19):9714–9721. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hyun T, Yam A, Pece S, et al. Loss of PTEN expression leading to high Akt activation in human multiple myelomas. Blood. 2000;96(10):3560–3568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsu J, Shi Y, Krajewski S, et al. The AKT kinase is activated in multiple myeloma tumor cells. Blood. 2001;98(9):2853–2855. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.9.2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahlis NJ, Miao Y, Koc ON, Lee K, Boise LH, Gerson SL. N-Benzoylstaurosporine (PKC412) inhibits Akt kinase inducing apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46(6):899–908. doi: 10.1080/10428190500080595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hideshima T, Catley L, Yasui H, et al. Perifosine, an oral bioactive novel alkylphospholipid, inhibits Akt and induces in vitro and in vivo cytotoxicity in human multiple myeloma cells. Blood. 2006;107(10):4053–4062. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Podar K, Raab MS, Zhang J, et al. Targeting PKC in multiple myeloma: in vitro and in vivo effects of the novel, orally available small-molecule inhibitor Enzastaurin (LY317615). Blood. 2007;109(4):1669–1677. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-042747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rizvi MA, Ghias K, Davies KM, et al. Enzastaurin (LY317615), a protein kinase Cbeta inhibitor, inhibits the AKT pathway and induces apoptosis in multiple myeloma cell lines. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5(7):1783–1789. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baughn LB, Di Liberto M, Wu K, et al. A novel orally active small molecule potently induces G1 arrest in primary myeloma cells and prevents tumor growth by specific inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6. Cancer Res. 2006;66(15):7661–7667. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hideshima T, Neri P, Tassone P, et al. MLN120B, a novel IkappaB kinase beta inhibitor, blocks multiple myeloma cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(19):5887–5894. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chesi M, Nardini E, Brents LA, et al. Frequent translocation t(4;14)(p16.3;q32.3) in multiple myeloma is associated with increased expression and activating mutations of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3. Nat Genet. 1997;16(3):260–264. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, Lee BH, Williams IR, et al. FGFR3 as a therapeutic target of the small molecule inhibitor PKC412 in hematopoietic malignancies. Oncogene. 2005;24(56):8259–8267. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trudel S, Li ZH, Wei E, et al. CHIR-258, a novel, multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor for the potential treatment of t(4;14) multiple myeloma. Blood. 2005;105(7):2941–2948. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plowright EE, Li Z, Bergsagel PL, et al. Ectopic expression of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 promotes myeloma cell proliferation and prevents apoptosis. Blood. 2000;95(3):992–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Z, Zhu YX, Plowright EE, et al. The myeloma-associated oncogene fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 is transforming in hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2001;97(8):2413–2419. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.8.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Root DE, Hacohen N, Hahn WC, Lander ES, Sabatini DM. Genome-scale loss-of-function screening with a lentiviral RNAi library. Nat Methods. 2006;3(9):715–719. doi: 10.1038/nmeth924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malo N, Hanley JA, Cerquozzi S, Pelletier J, Nadon R. Statistical practice in high-throughput screening data analysis. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24(2):167–175. doi: 10.1038/nbt1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tukey JW. A survey of sampling from contaminated distributions. In: Olkin I, editor. Contributions to Probability and Statistics. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1960. pp. 448–485. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brideau C, Gunter B, Pikounis B, Liaw A. Improved statistical methods for hit selection in high-throughput screening. J Biomol Screen. 2003;8(6):634–647. doi: 10.1177/1087057103258285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chng WJ, Kumar S, Vanwier S, et al. Molecular dissection of hyperdiploid multiple myeloma by gene expression profiling. Cancer Res. 2007;67(7):2982–2989. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su AI, Cooke MP, Ching KA, et al. Large-scale analysis of the human and mouse transcriptomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(7):4465–4470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012025199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID). [Accessed May 27, 2007]. http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov.

- 23.Nikolaev AY, Li M, Puskas N, Qin J, Gu W. Parc: a cytoplasmic anchor for p53. Cell. 2003;112(1):29–40. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01255-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou H, Yan F, Tai HH. Phosphorylation and desensitization of the human thromboxane receptor-alpha by G protein-coupled receptor kinases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298(3):1243–1251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Podar K, Tai YT, Davies FE, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor triggers signaling cascades mediating multiple myeloma cell growth and migration. Blood. 2001;98(2):428–435. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.2.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forbes S, Clements J, Dawson E, et al. Cosmic 2005. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(2):318–322. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephens P, Edkins S, Davies H, et al. A screen of the complete protein kinase gene family identifies diverse patterns of somatic mutations in human breast cancer. Nat Genet. 2005;37(6):590–592. doi: 10.1038/ng1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benovic JL, Gomez J. Molecular cloning and expression of GRK6: a new member of the G protein-coupled receptor kinase family. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(26):19521–19527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukai H, Ono Y. A novel protein kinase with leucine zipper-like sequences: its catalytic domain is highly homologous to that of protein kinase C. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;199(2):897–904. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dzimiri N, Muiya P, Andres E, Al-Halees Z. Differential functional expression of human myocardial G protein receptor kinases in left ventricular cardiac diseases. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;489(3):167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fong AM, Premont RT, Richardson RM, Yu Y-RA, Lefkowitz RJ, Patel DD. Defective lymphocyte chemotaxis in beta-arrestin2- and GRK6-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(11):7478–7483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112198299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo J, Benovic JL. G protein-coupled receptor kinase interaction with Hsp90 mediates kinase maturation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(51):50908–50914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307637200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duus J, Bahar HI, Venkataraman G, et al. Analysis of expression of heat shock protein-90 (HSP90) and the effects of HSP90 inhibitor (17-AAG) in multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47(7):1369–1378. doi: 10.1080/10428190500472123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitsiades CS, Mitsiades NS, McMullan CJ, et al. Antimyeloma activity of heat shock protein-90 inhibition. Blood. 2006;107(3):1092–1100. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Darnell JE, Jr., Kerr IM, Stark GR. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science. 1994;264(5164):1415–1421. doi: 10.1126/science.8197455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bromberg JF, Wrzeszczynska MH, Devgan G, et al. Stat3 as an Oncogene. Cell. 1999;98(3):295–303. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81959-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frank DA. STAT3 as a central mediator of neoplastic cellular transformation. Cancer Lett. 2007;251(2):199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brocke-Heidrich K, Kretzschmar AK, Pfeifer G, et al. Interleukin-6-dependent gene expression profiles in multiple myeloma INA-6 cells reveal a Bcl-2 family-independent survival pathway closely associated with Stat3 activation. Blood. 2004;103(1):242–251. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bharti AC, Shishodia S, Reuben JM, et al. Nuclear factor-kappaB and STAT3 are constitutively active in CD138+ cells derived from multiple myeloma patients, and suppression of these transcription factors leads to apoptosis. Blood. 2004;103(8):3175–3184. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nelson EA, Walker SR, Kepich A, et al. Nifuroxazide inhibits survival of multiple myeloma cells by directly inhibiting STAT3. Blood. 2008;112(13):5095–5102. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-129718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pathak AK, Bhutani M, Nair AS, et al. Ursolic acid inhibits STAT3 activation pathway leading to suppression of proliferation and chemosensitization of human multiple myeloma cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5(9):943–955. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Puthier D, Bataille R, Amiot M. IL-6 up-regulates mcl-1 in human myeloma cells through JAK/STAT rather than ras/MAP kinase pathway. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29(12):3945–3950. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199912)29:12<3945::AID-IMMU3945>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Le Gouill S, Podar K, Harousseau JL, Anderson KC. Mcl-1 regulation and its role in multiple myeloma. Cell Cycle. 2004;3(10):1259–1262. doi: 10.4161/cc.3.10.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burger M, Hartmann T, Burger JA, Schraufstatter I. KSHV-GPCR and CXCR2 transforming capacity and angiogenic responses are mediated through a JAK2-STAT3-dependent pathway. Oncogene. 2005;24(12):2067–2075. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrand A, Kowalski-Chauvel A, Bertrand C, et al. A novel mechanism for JAK2 activation by a G protein-coupled receptor, the CCK2R: implication of this signaling pathway in pancreatic tumor models. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(11):10710–10715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413309200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pelletier S, Duhamel F, Coulombe P, Popoff MR, Meloche S. Rho family GTPases are required for activation of Jak/STAT signaling by G protein-coupled receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(4):1316–1333. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.4.1316-1333.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ram PT, Iyengar R. G protein coupled receptor signaling through the Src and Stat3 pathway: role in proliferation and transformation. Oncogene. 2001;20(13):1601–1606. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu EH, Lo RK, Wong YH. Regulation of STAT3 activity by G16-coupled receptors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;303(3):920–925. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00451-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Freedman NJ, Ament AS, Oppermann M, Stoffel RH, Exum ST, Lefkowitz RJ. Phosphorylation and desensitization of human endothelin A and B receptors: evidence for G protein-coupled receptor kinase specificity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(28):17734–17743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vroon A, Heijnen CJ, Raatgever R, et al. GRK6 deficiency is associated with enhanced CXCR4-mediated neutrophil chemotaxis in vitro and impaired responsiveness to G-CSF in vivo. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75(4):698–704. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0703320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]