Abstract

Two patients with homocystinuria are discussed. Both patients presented with behavioural abnormalities and deficits in attention – symptoms that are frequently encountered in paediatric office practice. In both cases, the diagnosis of homocystinuria was not made at initial presentation. Subtle but definite phenotypic features eventually provided the first indication of homocystinuria between the ages of five to seven years. Laboratory screening confirmed homocystine in the urine, and elevated methionine and homocysteine plasma levels in both patients. Patients with inborn errors of metabolism such as homocystinuria are treated first by family physicians and paediatricians. Without a high index of suspicion, physicians can easily overlook a diagnosis of homocystinuria. The management of patients with homocystinuria continues to pose a challenge to physicians and care givers.

Keywords: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, Cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency, Developmental delay, Homocystinuria, Lens dislocation

Abstract

Deux patients atteints d’homocystinurie sont présentés. Tous deux affichaient des anomalies de comportement et un déficit de l’attention, des symptômes souvent observés dans le cabinet des pédiatres. Dans les deux cas, le diagnostic d’homocystinurie n’a pas été posé à la première visite. Des traits phénotypiques subtils mais établis ont fini par fournir la première indication d’homocystinurie entre l’âge de cinq et sept ans. Des examens de laboratoire ont confirmé la présence d’homocystine dans l’urine, ainsi qu’une élévation du taux de méthionine et d’homocystine plasmatique chez les deux patients. Les patients atteints d’une erreur innée du métabolisme comme l’homocystinurie sont d’abord traités par des médecins de famille ou des pédiatres. Sans un indice de suspicion élevé, il est facile pour les médecins d’omettre la possibilité d’homocystinurie. Le traitement des patients atteints d’homocystinurie continue de représenter un défi pour les médecins et les soignants.

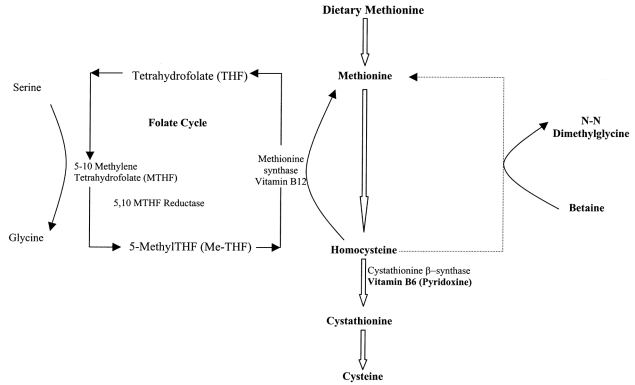

Hypermethioninemia and homocystinuria (hyperhomocyst[e]inemia) are terms used to describe biochemical abnormalities arising as a consequence of metabolic perturbation in the transsulfuration pathway (1) (Figure 1). These biochemical disturbances have both genetic and nongenetic causes (Table 1). The present paper describes two patients in whom the diagnosis of homocystinuria was made after the early childhood years. The patients’ clinical features were nonspecific, but biochemical findings confirmed the diagnosis. Clinical variability in the phenotypic features of homocystinuria is well recognized (2,3); as a result, the condition may be overlooked. Metabolic disorders, although rare, should be considered in the differential diagnosis of children presenting with the common symptoms of developmental delay, and attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (3).

Figure 1).

The metabolism of methionine, homocysteine and cystathionine. The principal pathway for the metabolism of dietary methionine is through conversion of homocysteine to cysteine. Folate and vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) are important cofactors in the metabolism of homocysteine, while introduction of betaine leads to remethylation of homocysteine to methionine and degradation of pathways other than trans-sulfuration

TABLE 1:

Differential diagnoses of homocyst(e)inemia

| Genetic disorders | Biochemical findings |

|---|---|

| Impaired activity of cystathionine beta-synthase enzyme (homocystinuria) | • Increased plasma methionine, homocysteine • Decreased cysteine, no cystathionine |

| 5,10-Methylenetetrahydrofolate (MTHFR) deficiency and thermolabile variant of MTHFR | • Increased plasma homocysteine • Decreased or normal methionine • Decreased folate, normal vitamin B12 |

| Defects in vitamin B12 metabolism | • Increased plasma homocysteine and methylmalonic acid in urine |

| Cobalamin defects (C,D,E,F and G) | • Decreased or normal methionine, normal cysteine |

| Transcobalamin deficiency | |

| Immerslund syndrome | |

| Nongenetic disorders | |

| Nutritional B12 deficiency | • Increased homocysteine, methylmalonic acid |

| Renal insufficiency | • Increased homocysteine |

| Pregnancy | |

| Nutritional folic acid deficiency | |

| Drug related | |

| Isonicotinic acid hydrazide therapy | |

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Case 1

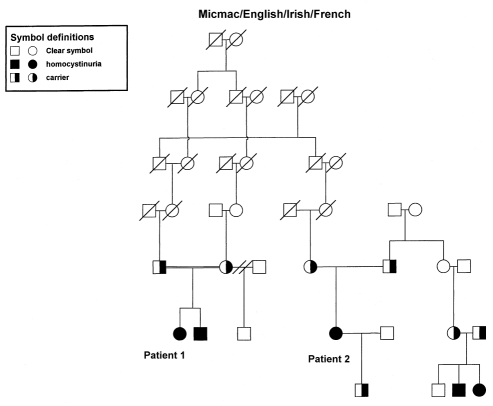

A six-year-old girl was referred to the Child Development Clinic at the Janeway Child Health Centre, St John’s, Newfoundland for evaluation of impulsivity, hyperactivity and poor school performance of one-year duration. She was born at 39 weeks’ gestation with a birth weight of 4.2 kg to a Gravida II, Para I mother following an uncomplicated pregnancy, labour and delivery. The mother was maintained on thyroxine supplements for a previous history of hypothyroidism during pregnancy. The infant received phototherapy for neonatal hyperbilirubinemia. Her developmental milestones were normal in the first year, but subsequently she was noted to be clumsy. She had an inguinal hernia that was repaired at two years of age. She was given shoe inserts for gait difficulties at three years of age. Upon entering kindergarten, she was noted to have a speech delay. She was prescribed corrective eye lenses for myopia at school entry, but did not undergo a detailed ophthalmologic evaluation at the time. Her classroom behaviour, characterized by hyperactivity and attention difficulties, prompted an evaluation by the school psychologist, and a referral for further clinical evaluation. There was no history of seizures, loss of consciousness or developmental regression. Both maternal and paternal families are of Aboriginal and Irish descent. Her parents are third cousins (Figure 2).

Figure 2).

Pedigree showing autosomal recessive inheritance of homocystinuria and inter-relationship between the two affected cases

Physical examination revealed a girl who was 130 cm tall (98th percentile), weighed 26 kg (between 90th to 95th percentile) and had a head circumference of 51.5 cm (50th percentile). Facial features showed subtle dysmorphism and mild frontal bossing. A livedo reticularis pattern was present on her skin. Her scalp hair was thin, brittle and lustreless. She had a high myopic refractive error (Figure 3). A high arched palate, mild pectus excavatum, long and slender fingers, joint hypermobility and flat feet were also noted. Neurological examination revealed normal cranial nerves II to XII; motor and sensory examinations were normal. The patient’s hearing was normal. There was no scoliosis on musculoskeletal examination. A formal ophthalmologic examination showed bilateral lens subluxation. The combination of ocular findings and phenotypic features suggested homocystinuria as the underlying metabolic cause for her developmental delay. The diagnosis was confirmed by a quantitative analysis of plasma amino acids, which showed elevated methionine of 586 μmol/L (normal 7 to 47 μmol/L), homocysteine of 295 μmol/L (normal 0 to 17 μmol/L), and a low cysteine value of 2 μmol/L (normal 5 to 45 μmol/L), while red blood cell folate and serum vitamin B12 levels were normal. Urinary homocystine levels were elevated at 586 μmol/mmol creatinine (normal 0 to 9 μmol/mmol creatinine). Methylmalonic acid was not detected during urine organic acid analysis. A skeletal survey showed mild generalized osteoporosis. A cranial computed tomography scan and electroencephalogram were normal.

Figure 3).

Frontal views of patient in case presentation 1 showing relative nonspecific facial features and the high myopic refractive error

The diagnosis of classic homocystinuria was conclusively established with the confirmation of cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency in cultured fibroblasts. The patient began pyridoxine 500 mg once a day, folic acid 5 mg once a day and a low methionine diet. Dietary compliance to date has been poor. The patient showed no biochemical response to pyridoxine administration. With the introduction of betaine at 3 g twice a day, plasma homocysteine values decreased marginally. She has also been started on methylphenidate (Ritalin, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada Inc, Dorval, Quebec) therapy. Her attention span has shown some improvement since therapy was initiated.

The mother of this patient subsequently delivered a male infant who was found to have elevated methionine levels during newborn screening. The parents had declined prenatal diagnosis. The diagnosis of homocystinuria in the male child due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency was confirmed by enzymatic assay on fibroblasts. He is currently 11 months old and is receiving pyridoxine, folic acid and a low methionine diet. So far he has shown good clinical and biochemical response.

Case 2

A 30-year-old woman with homocystinuria from the same geographical region as the previous female patient has been followed intermittently by the provincial genetics program. The diagnosis of homocystinuria was made at seven years of age. The patient is a third cousin to the first case, and one of her first cousins has two children with homocystinuria (Figure 2). She was born at term with a weight of 4 kg following a normal pregnancy and labour. At three weeks of age, she developed seizures that remitted spontaneously. Developmental milestones were delayed. The patient sat without support at one year of age, and walked independently at two years of age. She required orthopedic intervention for her flat feet and varus deformity of her hips. At seven years of age, she underwent investigations for developmental delay and attention problems. Plasma amino acid analysis demonstrated elevated methionine and homocysteine levels, and a skeletal survey revealed osteoporosis. Ophthalmologic evaluation revealed dislocated lenses bilaterally. The diagnosis of homocystinuria was, thus, established. Pyridoxine and folate therapies were initiated. Compliance to treatment was not strict, and she was lost to follow-up.

The patient completed a grade one education. At 21 years of age, she was re-evaluated for mental retardation, psychiatric problems with multiple suicide attempts, aggressive behaviour and problems with the law. She required management with antipsychotic medication. Other medical issues included headaches, asthma, chest pain and deep vein thrombosis in her legs. For the most part, the patient remained in a group home, and treatment compliance was a major problem. At 29 years of age, she delivered a normal male infant after an unremarkable pregnancy. At 30 years of age, she was re-evaluated to optimize metabolic control. On examination, she appeared obese, her weight was 90 kg (above the 95th percentile) and her height was 175 cm (above the 95th percentile). She did not have a Marfanoid habitus. She was strongly myopic. Facial dysmorphism was not present. The patient had long and slender fingers without hypermobile joints. A scar from the surgical removal of a clot was present on her left ankle. A formal psychological assessment was not done. Neurological evaluation was significant for poor comprehension, limited reading and writing skills, and a marked inability to perform fine motor skills. In her cognitive abilities, she was performing at a five to six year level. An analysis of the patient’s most recent quantitative plasma amino acids revealed normal cysteine value of 26 μmol/L (normal five to 45 μmol/L), elevated methionine levels of 555 μmol/L (normal 7 to 47 μmol/L) and homocysteine levels of 231 μmol/L (normal 0 to 17 μmol/L). Serum vitamin B12 and red cell folate levels were normal. The patient remains severely affected by homocystinuria, and requires constant supervision to perform activities of daily living and infant care tasks. As with the previous case, compliance with diet and medications is poor.

DISCUSSION

Homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency is an inborn error of metabolism with phenotypic features that for the most part are readily identified (2,3). The principal clinical features of homocystinuria are summarized in Table 2. Because of numerous complications, such as increased tendency to strokes, ocular symptoms and neuropsychiatric abnormalities, regular medical follow-up is imperative. Recently, there has been renewed interest in the relationship between elevated homocysteine levels and the occurrence of vascular complications (4,5).

TABLE 2:

Clinical features of homocystinuria

| Major features | Minor features | Other features |

|---|---|---|

| Lens dislocation | Long and slender fingers | Fair skin |

| Myopia | Glaucoma | Malar flush |

| Thin, long bones: dolichostenomelia | Seizures | Livedo reticularis |

| Osteoporosis | Psychiatric disturbances | Brittle, thin hair |

| Mental retardation | Genu valgum | Inguinal hernia |

| Arterial and venous thromboembolism | Scoliosis | High arched palate |

The inheritance pattern of homocystinuria is autosomal recessive, and the reported incidence varies from 1/67,000 to 1/200,000, with a higher risk in individuals who are of Irish descent or from New South Wales, Australia (1,6). The gene for cystathionine beta-synthase is located on the long arm of chromosome 21 band 22.3. Sixty-four mutations affecting this gene have been described (7); the most frequent are 1278T (24%) and G3075 (31%). The importance of molecular analysis lies in establishing a genotype-phenotype correlation that is helpful in predicting a patient’s response to pyridoxine, which in turn may have implications for long term outcome. Vitamin B6 responsive patients are likely to have a lower incidence of complications, while mental retardation occurs more often in patients who are nonresponsive to vitamin B6. Aggressive behaviour and conduct disorders are also seen more commonly in this subgroup (8).

A condensed version of the principal pathways involved in homocysteine metabolism, and the role of folic acid and pyridoxine (important cofactors) are depicted in Figure 1. Longhi et al (9) reported that half of the patients studied were responsive to pyridoxine, which improves the residual enzyme activity. Folic acid is helpful as an adjunct therapy in patients who are responsive to pyridoxine (10). Betaine, which uses an alternative pathway of remethylation of homocysteine to methionine, has been used in patients who are unresponsive to pyridoxine (11,12). Evidence demonstrates that the appropriate treatment of homocystinuria markedly reduces the risk of vascular complications, even if biochemical control is suboptimal (13).

The two female patients described above were referred for an evaluation of their attention problems and developmental disabilities, and not for an evaluation of the classical features of homocystinuria described in the literature. ADHD is a relatively common disorder, occurring in 5% to 6% of school age children (14). Boys are more commonly affected than girls. ADHD is diagnosed on the basis of criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) (15). Attention and behavioural issues in the first patient masked the subtle physical features of homocystinuria. In the second patient, the diagnosis of homocystinuria was similarly established during investigation of developmental delay at seven years of age. Despite a positive history of homocystinuria in the second patient’s cousins, a diagnosis of homocystinuria was not considered until she was seven years of age. In both instances, the abnormal amino acid profile obtained on screening pointed to the diagnosis of homocystinuria. In both patients, the ophthalmic findings, skeletal changes and biochemical abnormalities were similar. The clinical course of both patients illustrates the difficulties inherent in initiating treatment at a late stage and the challenges in management. The first case presented with ADHD, while the second, the presentation was significant for developmental delay and attention problems during childhood and psychiatric manifestations in later life. Both patients are unresponsive to pyridoxine, and are severely affected.

Delayed diagnosis of homocystinuria decreases the likelihood of optimal developmental outcome, and leads to an increased risk of systemic consequences. Earlier case detection, along with the introduction of a low methionine diet and pyridoxine supplements, is associated with a better prognosis (16), thus providing evidence for including the detection of homocystinuria in the newborn screening programs (2). More studies to examine the incidence of this disorder and to confirm the effectiveness of early intervention are necessary.

Dietary methionine restriction and vitamin supplements have been ineffective in both patients described. There are, in addition, a number of social and behavioural issues such as disruptive and aggressive behaviours; these were encountered in our second patient and required multiple psychiatric interventions. Psychiatric manifestations are well recognized in patients with homocystinuria, and include: episodic depression, chronic behaviour disorder, obsessive compulsive disorders and personality disorders (8).

There are very few reports of pregnancies in females with homocystinuria. Pregnancy in an affected female carries an increased risk of miscarriage, as well as a definite risk of a thromboembolic event (17). In spite of her poor metabolic control and no anticoagulation treatment, the second patient had an almost uneventful pregnancy with a normal outcome.

CONCLUSIONS

The consideration of metabolic etiologies in the investigation of ADHD and developmental delay in the pre-school and childhood periods is essential for the early identification of patients with homocystinuria. Because routine newborn screening is not available for many metabolic disorders including homocystinuria, basic guidelines for metabolic testing are outlined in Table 3. The authors recommend careful clinical evaluation in order to direct the investigations appropriately, which may include other genetic investigations such as a karyotype and/or molecular studies to rule out fragile X syndrome. Apart from the management of the individual patient and the complications that can arise during his or her lifespan, parents of a child with homocystinuria should be made aware of the 25% recurrence risk in a subsequent pregnancy, and the likelihood that other individuals in the extended family are potential carriers.

TABLE 3:

Suggested metabolic investigations for a patient with developmental delay and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

| Investigations | Disorders |

|---|---|

| Plasma and urine aminoacids | Aminoacidopathies |

| Phenylketonuria | |

| Homocystinuria | |

| Branched chain aminoacidopathies | |

| Urea cycle defects | |

| Serum uric acid levels | Lesch-Nyhan syndrome |

| Plasma ammonia levels | Urea cycle defects |

| Organic acidemias | |

| Plasma lactate levels | Mitochondrial cytopathies |

| Urinary mucopolysaccharides and oligosaccharides | Lysosomal storage disorders |

| Skeletal survey | Dysostosis multiplex in mucopolysaccharidoses |

| Ophthalmic slit-lamp examination | Lens dislocation in homocystinuria |

| Corneal clouding in mucopolysaccharidoses |

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ann Duff and David Macgregor of the Newfoundland and Labrador Medical Genetics Program for their help with data collection, Dr E Randell, of the Janeway Child Health Centre, St John’s, Newfoundland for his help with the biochemical analyses on the patients; Dr Cheryl R Greenberg and Louise Dilling, Section of Genetics and Metabolism, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital, Winnipeg, Manitoba for their comments and suggestions. We are grateful to our patients and their families for their cooperation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mudd S, Levy H, Skovby F. Disorders of transsulfuration. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Vale D, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 7th edn. Vol. 1. New York: McGraw-Hill Inc; 1995. pp. 1279–327. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mudd SH, Skovby F, Levy HL, et al. The natural history of homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 1985;37:1–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Franchis R, Sperandeo MP, Sebastio G, Andria G. Clinical aspects of cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency: how wide is the spectrum? The Italian Collaborative Study Group on Homocystinuria. Eur J Pediatr. 1998;157(Suppl 2):S67–70. doi: 10.1007/pl00014309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarke R, Daly L, Robinson K, et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia: an independent risk factor for vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1149–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199104253241701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson K, Mayer E, Jacobsen DW. Homocysteine and coronary artery disease. Cleve Clin J Med. 1994;61:438–50. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.61.6.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naughten ER, Yap S, Mayne PD. Newborn screening for homocystinuria: Irish and world experience. Eur J Pediatr. 1998;157(Suppl 2):S84–7. doi: 10.1007/pl00014310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kraus JP. Biochemistry and molecular genetics of cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency. Eur J Pediatr. 1998;157(Suppl 2):S50–3. doi: 10.1007/pl00014304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbott MH, Folstein SE, Abbey H, Pyeritz RE. Psychiatric manifestations of homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency: prevalence, natural history, and relationship to neurologic impairment and vitamin B6-responsiveness. Am J Med Genet. 1987;26:959–69. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320260427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Longhi RC, Fleisher LD, Tallan HH, Gaull GE. Cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency: a qualitative abnormality of the deficient enzyme modified by vitamin B6 therapy. Pediatr Res. 1977;11:100–3. doi: 10.1203/00006450-197702000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walter JH, Wraith JE, White FJ, Bridge C, Till J. Strategies for the treatment of cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency: the experience of the Willink Biochemical Genetics Unit over the past 30 years. Eur J Pediatr. 1998;157(Suppl 2):S71–6. doi: 10.1007/pl00014308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilcken DE, Wilcken B, Dudman NP, Tyrrell PA. Homocystinuria –the effects of betaine in the treatment of patients not responsive to pyridoxine. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:448–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198308253090802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilcken DE, Dudman NP, Tyrrell PA. Homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency – the effects of betaine treatment in pyridoxine-responsive patients. Metabolism. 1985;34:1115–21. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(85)90156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilcken DE, Wilcken B. The natural history of vascular disease in homocystinuria and the effects of treatment. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1997;20:295–300. doi: 10.1023/a:1005373209964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swanson JM, Sergeant JA, Taylor E, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Jensen PS, Cantwell DP. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and hyperkinetic disorder. Lancet. 1998;351:429–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenhill LL. Diagnosing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 7):31–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schimke RN. Low methionine diet treatment of homocystinuria. Ann Intern Med. 1969;70:642–3. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-70-3-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newman G, Mitchell JR. Homocystinuria presenting as multiple arterial occlusions. Q J Med. 1984;53:251–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]