“Children aged one to five, who develop to their maximum potential in the preschool years have age appropriate social skills, language and learning skills, good emotional health and good physical health.”

(1)

Traditionally, the term ‘deprived preschooler’ has referred to a child who is missing components in his or her experiential world that affect or have the capacity to affect his or her ultimate development. However, because no experiential world is ‘development perfect’ for any child, many preschoolers may be considered to have a degree of deprivation.

In the past few decades, much has been learned about factors that both enhance and impede a preschooler’s development. Positive development in the preschool years is greatly enhanced by relationships with parents and other significant adults; supportive communities; a healthy physical environment and protection from injuries; experiences with other children; nutrition, exercise and preventive care; and quality care and preschool education (1).

Preschoolers build their future abilities on the foundations of their earliest brain development, which occurs in the prenatal and infant periods. This becomes their pathway to future success through lifelong learning, adaptive behaviours and good health.

Although some brain development is controlled through the genome (nature versus nurture), neuroscientific research from the past 10 to 15 years indicates that dendrite growth and the architectural shaping of the brain are directly linked to early stimulation and care (nurture versus nature). Hard wiring of the brain is determined by the interplay of stimulation experienced through the various sensory pathways during the first few years of life. In other words, gene effects on the structure of the brain vary with the environment in which the development is taking place (2). Pathways of repeated stimulation persist, while others are pruned away. Although this process is not fully understood, it appears that when electrical activity is produced through neural pathway activation, it results in chemical changes that stabilize a synapse (3). As a result, early experiences will determine the adult that a child will become in much larger measure than previously understood.

As well, critical periods of development occur when certain capacities unfold. Vision, emotional control, habitual ways of responding to stimuli and language development all occur rapidly before one year of age. During the preschool years, these skills are consolidated, and other skills, such as socialization, cognitive (ie, concepts of symbols and relative quantity) and further language, develop (4).

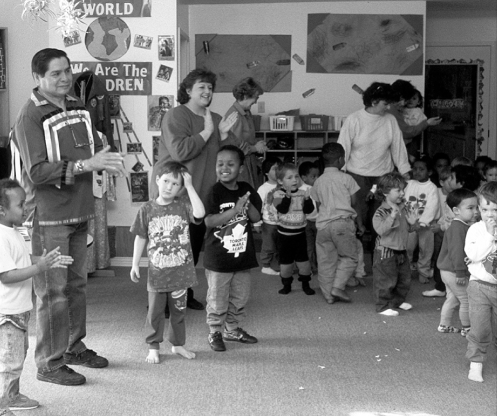

As a child grows and develops, the setting for acquiring the above skills changes. In infancy, the primary relationship with mothers and fathers (or primary caretakers), which is paramount, gradually broadens to embrace others within the family and community. By the preschool years, life-forming experiences occur in the ‘village’ (from the African proverb “It takes a village to raise a child.”) that surrounds the child (Figure 1).

Figure 1).

By the preschool years, life-forming experiences occur in the ‘village’ that surrounds the child. Photograph courtesy of Health Canada

When one tries to determine how Canadian preschoolers are faring, one soon discovers the paucity of population-based indicators that measure a child’s developmental success or failure. Indicators of physical health, mortality and hospitalization rates, are available. Preschoolers have a progressively decreasing death rate (the leading cause is injuries) and a declining hospitalization rate (the leading cause is respiratory disease) (5). However, data about the preschoolers’ emotional and mental health are not available (5). Targeted rates, such as the number of children being reared in poverty (1.2 million children or one in five children [5]), the percentage of children living in poor, single parent families (45% [5]), or the rates of child abuse, are available and imply a significant problem within the Canadian preschool population.

Paediatricians and family practitioners have access to the preschool population during routine and acute (episodic) care, and may fulfil traditional paediatric functions at the individual level. These include ensuring that a child’s physical health (eg, immunization) is attended to, and examining a child’s progress with regard to social and emotional development. Paediatricians, either directly or through referrals, can teach parents about parenting and child development, emphasize the importance of a safe and secure environment for life and play, highlight the significance of nutrition, exercise and preventive care, and emphasize the importance of providing children with opportunities for peer experiences.

At the extremes of the preschool experience, where deprivation is a concern, the paediatrician may pursue specific help for a child through a referral to children’s mental health services, a mandatory referral to child welfare agencies or daycare, etc.

The needs of all preschoolers, deprived or otherwise, go beyond the individual treatments and personal relationships that paediatricians can provide. Today’s paediatrician also has a role to play in the community. The first task for a paediatrician is to have a good working knowledge of services that are available in the community. This is best obtained through on-site visits to the local child welfare agency, the children’s mental health agency and other specialized programs such as therapeutic nurseries or specialty daycares where enhanced resources (eg, psychiatrists, psychologists) are available to the mother or the father and to the child. The investment of a few hours upfront to develop this knowledge and network in the local community is critical to achieving longer term effectiveness as a clinician. Just as understanding the side effects and contraindications of medications at the individual level is critical, the understanding of community ‘therapies’ is critical to make appropriate referrals and have paediatric clients accepted into community services.

Furthermore, a special onus falls on the paediatrician to work with the community to develop the environments and resources that will support preschoolers and their parents. Others have written eloquently about physician leaders who help communities come together to promote the betterment of children in Canada (6), but participation by the paediatrician on community action groups that focus on the importance of the early years is critical. These groups consist of community collaborations of like-minded key decision-makers who can advocate for an economic safety net, supplemented by a developmental safety net. For the preschooler, these safety nets must include the following: increasing public awareness of the fundamental importance of a child’s experience in his or her early years to human development; providing preschools and parent resource centres; establishing parenting groups; ensuring that primary schools are prepared to meet the developmental needs of preschoolers; providing safe, accessible, well-maintained and well-equipped environments (inside and out of preschools) for preschooler play; establishing preschooler injury prevention programs; providing accessible, quality, family-centred daycare; creating family-friendly workplaces that support families and preschoolers through on-site daycare and flexible work hours; and ensuring an adequate and a stable standard of living for families with preschoolers.

The opportunity for paediatricians to make a difference in the world of preschoolers is significant, not only for the most traditionally deprived child, but also for the large numbers of young children who would benefit from a better ‘village’. These children will produce the civil society and the economic basis on which Canada will face the future and its challenges. Like the Companions of the Order of Canada who have banded together to speak out against child poverty, paediatricians must advocate and act on behalf of children because “the well being of Canada’s children is a sacred trust that we ignore at our peril” (7).

REFERENCES

- 1.Growing Healthy Canadians, A Framework for Positive Child Development. Ottawa: The Alder Group Inc; 1999. Promotion and Prevention Task Force of the Sparrow Lake Alliance and the Strategic Funding Group of the Funders Alliance for Children, Youth and Families. < childdev.web.net>. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenberg L. Experience, brain and behaviour: The importance of a head start. American Academy of Paediatrics. Paediatrics. 1999;103:1031–4. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.5.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shore R. Rethinking the Brain. New York: The Alder Group Families and Work Institute; 1997. p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCain MN, Mustard JF. Reversing the Real Brain Drain, Early Years Study, Final Report 1999. Toronto: Publications Ontario; 1999. p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harvey L, Avard DM, Graham I, Underwood K, Campbell J, Kelly C. The Health of Canada’s Children: A CICH Profile. 2nd edn. Ottawa: Canadian Institute of Child Health; 1994. pp. 41–56. & 115:121. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avard DM, Chance GW. Canada’s poorest citizens: looking for solutions for children. CMAJ. 1994;151:419–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campaign Against Child Poverty. The Globe and Mail, May 23, 1999:A6. (Advertisement)