Abstract

Background

In July 2009, Medicare will begin publicly reporting hospitals’ risk-standardized, all-cause 30-day readmission rates (RSRRs) among fee-for-service beneficiaries discharged after heart failure hospitalization from all U.S. acute care non-federal hospitals. No recent national trends in RSRRs have been reported and it is not known if hospital-specific performance is improving or if variation in performance is decreasing.

Methods and Results

We used 2004–2006 Medicare administrative data to identify all fee-for-service beneficiaries admitted to a U.S. acute care hospital for heart failure and discharged alive. We estimated mean annual RSRRs, a National Quality Forum-endorsed metric for quality, using two-level hierarchical models that accounted for age, sex, and multiple co-morbidities; variation in quality was estimated by the standard deviation of the RSRRs. There were 570,996 distinct hospitalizations for heart failure in which the patient was discharged alive in 4728 hospitals in 2004; 544,550 in 4694 hospitals in 2005; and 501,234 in 4674 hospitals in 2006. Unadjusted 30-day all-cause readmission rates were virtually identical over this period: 23.0% in 2004, 23.3% in 2005, and 22.9% in 2006. The mean and standard deviation (SD) of RSRRs were also similar: mean [SD] of 23.7% [1.3] in 2004, 23.9% [1.4] in 2005, and 23.8% [1.4] in 2006, suggesting similar hospital variation throughout the study period.

Conclusions

National mean and RSRR distributions among Medicare beneficiaries discharged after heart failure hospitalization have not changed in recent years, indicating that there was neither improvement in hospital readmission rates nor in hospital variations in rates over this time period.

Keywords: Heart Failure, Congestive, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (U.S.), Patient Readmission, United States/epidemiology

BACKGROUND

As a measure of performance quality, the Center of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) will begin publicly-reporting hospitals’ risk-standardized 30-day all-cause readmission rates (RSRRs), among fee-for-service beneficiaries discharged after hospitalization for heart failure (HF) from all U.S. acute care non-federal hospitals, in July 2009. This focus on readmission is part of a larger CMS effort to promote health care quality and efficiency1 and was supported by reports from both the Institute of Medicine and the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MEDPAC) that identified hospital readmissions as potential indicators of poor care or missed opportunities to better coordinate care.2, 3 The RSRR was endorsed by the National Quality Forum as a measure of hospital performance4 and is aligned with the American Heart Association’s and American College of Cardiology's published standards for statistical models used for calculation and public reporting of health outcomes and efficiency measures.5, 6

Policies that target readmission after HF hospitalization through public reporting to drive improved performance have widespread potential. Readmission rates may be reduced if proven interventions are more fully instituted by hospitals and physicians in response to public reporting and benchmarking. HF is one of the most common principal discharge diagnoses among Medicare beneficiaries7 and there is wide variation among hospitals’ HF readmission rates.3 After hospitalization for HF, 15-day readmission rates have been estimated at 13%3 and 30-day readmission rates at approximately 25%.8, 9 Other studies reported rates of readmission after HF hospitalization approaching 45% at six months in the same population.10 In efforts to identify opportunities to improve quality of care, several interventions have been proven to lower readmission rates after HF hospitalization, including improved hospital11, 12 and post-discharge care,13–17 pre-discharge planning,18, 19 home-based follow-up,20 and patient education.18, 21, 22

Despite the planned public reporting of RSRRs by CMS, the most recent estimates of U.S. readmission rates after HF hospitalization are from 20049 and it is not known whether mean hospital-specific performance has been improving, staying the same, or getting worse. Moreover, it is not known whether between-hospital variation in RSRR has changed; decreased variation would suggest that more hospitals are performing at more or less the same level, whereas increased variation would suggest that more hospitals are substantially out-performing and under-performing the others. Our research objective was to describe recent national trends in 30-day all-cause readmission rates after HF hospitalization among Medicare beneficiaries in order to improve clinical understanding of the risk for re-hospitalization after HF admission and to inform efforts of policy-makers as increased attention is focused on this new measure of hospital quality.

METHODS

Study Cohort

The study population included fee-for-service Medicare patients 65 years or older discharged alive after a hospitalization with a principal discharge diagnosis of HF between January 1, 2004, and December 31, 2006. HF hospitalizations were determined using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic codes, specifically the following codes: 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.03, 404.11, 404.13, 404.91, 404.93, and 428.x. Data were obtained from the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MEDPAR) files for each year (2004, 2005, and 2006) separately. We used Medicare Part A inpatient and outpatient data and Medicare Part B provider data to determine patient co-morbidities, past medical history, and procedure use during the 12 months before the index admission.

For each year of data, we included patients with 12 months of continuous Medicare fee-for-service enrollment before the index admission in order to obtain complete co-morbidity information. Because our focus was on hospital readmission risk, we excluded hospitalizations during which the patient died; the proportion of excluded hospitalizations did not vary by year. Patients who were transferred from an index hospital to another acute care facility were followed as a single episode of care. These patients were attributed to the receiving hospital that was responsible for their discharge because our focus was on hospital readmission risk, as done in prior research.8 Mortality was determined by linking the MEDPAR data with the Medicare Enrollment Database.

Hospital-Specific Readmission Rates

Our main outcome measure was hospital-specific, all-cause readmission rates for all HF hospitalizations where patients were discharged alive, defined using hospital rates of patient readmissions to any hospital for any reason within 30 days following discharge after an index HF hospitalization. During a calendar year, patients could have more than one HF hospitalization. However, HF hospitalizations that occurred within 30 days of discharge of an index discharge after HF hospitalization were categorized as outcome events (i.e., a readmission) and not treated as new index hospitalizations.

To calculate the hospital-specific RSRR, we used measurement methods that were developed for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and which have been endorsed by the National Quality Forum.4 These models are based on administrative data but produce estimates of RSRRs that are strongly correlated with estimates from a medical record model.8 This model includes patient-specific information on age and sex and uses condition categories, derived from hierarchical condition categories,23 to additionally include information on 9 characteristics from the cardiovascular medical history and 26 other co-morbid conditions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, cardiovascular past medical history, and co-morbid conditions for fee-for-service Medicare beneficiary discharges after heart failure hospitalization, stratified by year.

| Overall | Year | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | |||

| No. of Discharges (%) | 1,616,780 | 570,996 (35.3) | 544,550 (33.7) | 501,234 (31.0) | |

| Demographics | |||||

| Age: mean (SD) | 80.1 (7.9) | 79.9 (7.8) | 80.0 (7.9) | 80.3 (7.9) | <0.001 |

| Female, % | 57.3 | 57.8 | 57.1 | 56.9 | <0.001 |

|

Cardiovascular Past Medical History, % |

|||||

| History of CABG Surgery | 12.9 | 13.4 | 13.1 | 12.1 | <0.001 |

| Heart Failure (CC 80) | 74.1 | 74.0 | 74.4 | 74.0 | <0.001 |

| Acute coronary syndrome (CC 81, 82) | 19.6 | 20.4 | 19.5 | 18.8 | <0.001 |

| Arrhythmias (CC 92, 93) | 60.1 | 59.0 | 60.3 | 61.1 | <0.001 |

| Cardio-respiratory failure and shock (CC 79) |

17.3 | 17.0 | 17.0 | 18.0 | <0.001 |

| Valvular and rheumatic heart disease (CC 86) |

47.9 | 46.7 | 48.0 | 49.2 | <0.001 |

| Vascular or circulatory disease (CC 104–106) |

42.8 | 42.2 | 42.7 | 43.5 | <0.001 |

| Chronic atherosclerosis (CC 83, 84) | 72.8 | 72.9 | 72.9 | 72.4 | <0.001 |

| Other and unspecified heart disease (CC 94) |

18.6 | 18.4 | 18.6 | 18.8 | <0.001 |

| Co-morbid Condition, % | |||||

| Stroke (CC 95, 96) | 8.5 | 8.7 | 8.5 | 8.3 | <0.001 |

| End-stage renal disease or dialysis (CC 129, 130) |

3.2 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 3.5 | <0.001 |

| Renal Failure (CC 131) | 28.9 | 25.5 | 27.6 | 34.2 | <0.001 |

| Nephritis (CC 132) | 3.4 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 3.0 | <0.001 |

| Other urinary tract disorders (CC 136) |

36.0 | 37.6 | 37.8 | 32.2 | <0.001 |

| COPD (CC 108) | 44.8 | 44.7 | 44.8 | 45.0 | 0.001 |

| Asthma (CC 110) | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 0.98 |

| Pneumonia (CC 111–113) | 31.1 | 29.8 | 30.8 | 33.0 | <0.001 |

| Fibrosis of lung and other chronic lung disorders (CC 109) |

6.8 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 7.0 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes and diabetes mellitus complications (CC 15–20, 119, 120) |

49.2 | 48.9 | 49.3 | 49.5 | <0.001 |

| Liver and biliary disease (CC 25–30) | 6.0 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 0.01 |

| Peptic ulcer, hemorrhage, other specified GI disorders (CC 34) |

15.0 | 15.2 | 15.0 | 14.7 | <0.001 |

| Other GI disorders (CC 36) | 48.7 | 48.3 | 48.5 | 49.3 | <0.001 |

| Dementia and senility (CC 49, 50) | 15.8 | 15.3 | 15.8 | 16.5 | <0.001 |

| Depression (CC 58) | 12.5 | 12.6 | 12.4 | 12.5 | <0.001 |

| Major psychiatric disorders (CC 54– 56) |

7.7 | 7.7 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 0.003 |

| Other psychiatric disorders (CC 60) | 9.1 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.3 | <0.001 |

| Drug/alcohol abuse/ dependence/psychosis (CC 51–53) |

8.7 | 8.6 | 8.9 | 8.8 | <0.001 |

| Metastatic cancer and acute leukemia (CC 7) |

1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 0.06 |

| Cancer (nonmetastatic) (CC 8–12) | 18.9 | 18.6 | 18.8 | 19.2 | <0.001 |

| Severe hematologic disorders (CC 44) | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.5 | <0.001 |

| Iron deficiency and other/ unspecified anemias and blood disease (CC 47) |

44.9 | 44.2 | 44.8 | 45.8 | <0.001 |

| Hemiplegia, paraplegia, paralysis, functional disability (CC 67–69, 100– 102, 177, 178) |

5.9 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 5.8 | <0.001 |

| Decubitus ulcer or chronic skin ulcer (CC 148, 149) |

12.0 | 11.7 | 12.0 | 12.2 | <0.001 |

| Protein-calorie malnutrition (CC 21) | 4.7 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 5.1 | <0.001 |

| Disorders of fluid/electrolyte/ acid- base (CC 22–23) |

36.5 | 35.4 | 36.5 | 37.7 | <0.001 |

Note: SD=Standard Deviation; CC=Condition Category; CABG = Coronary Artery Bypass Graft; COPD = Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; GI=Gastrointestinal.

The hospital-specific RSRR was calculated from estimates derived from two-level (patient and hospital) hierarchical logistic regression models. In the hierarchical regression model, the dependent variable was patient-specific 30-day all-cause readmission. The first-level covariates include patient age, sex, co-morbid conditions, and cardiovascular medical history, as described above. The second-level covariates includes hospital-level random intercepts assumed to be normally distributed in order to account for the clustering (non-independence) of patients within the same hospital.24 This permitted separation of within-hospital and between-hospital variation after adjusting for patient characteristics.

Statistical Analysis

We compared patient characteristics across all three years using patient-level data, using a general linear model to compare the mean age of each year’s cohort and Chi Square tests to compare other categorical variables across all three years. National trends in hospital-specific readmission rates after HF hospitalization were analyzed using hospital-level data. We calculated the mean observed readmission rates and RSRRs, along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals, for the full three-year pooled sample and stratified by year and by the Census Division in which the hospital is located. Year and Census Division stratified estimates of the RSRR were conducted independently. To assess the effect of year and hospital Census Division on the estimated RSRRs, we fitted a hierarchical linear regression model that used the estimated RSRRs for each hospital as our dependent variable and accounted for repeated measures and imbalance due to not all hospitals having three years of data. All analyses were conducted using SAS Software, Version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). All statistical tests were two-tailed and used a type I error rate of 0.05.

RESULTS

After exclusions were applied, the 2004 data included 570,996 hospitalizations for HF in which the patient was discharged alive among 4728 hospitals, the 2005 data included 544,550 hospitalizations for HF in which the patient was discharged alive among 4694 hospitals, and the 2006 data included 501,234 hospitalizations for HF in which the patient was discharged alive among 4674 hospitals, for a total of 1,616,780 hospitalizations for HF in which the patient was discharged alive from 2004 through 2006. The average patient age was 80.1 years and 57.3% were female. The majority of these patients had multiple chronic diseases; 74.1% had been previously diagnosed with HF, 60.1% had been previously diagnosed with heart arrhythmias, 72.8% with chronic atherosclerosis, 49.2% with diabetes, and 28.9% with renal failure (Table 1).

Among 1,616,780 hospitalizations for HF in which the patient was discharged alive from 2004 through 2006, 384,397 (23.8%) were readmitted to a hospital for any reason within 30 days of discharge. Unadjusted hospital-specific 30-day all-cause readmission rates were virtually identical in each year over this period, although statistically different: mean [standard deviation (SD)] of 23.0% [9.9] in 2004, 23.3% [10.2] in 2005, and 22.9% [10.4] in 2006 (p=0.04; Table 2).

Table 2.

Observed and risk-standardized hospital- specific 30-day all-cause readmission rates for fee-for-service Medicare beneficiary discharges after heart failure hospitalization, stratified by year.

| Overall | Year | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | |||

| Observed Readmission Rate | |||||

| Mean [SD] | 23.1% [10.2] | 23.0% [9.9] | 23.3% [10.2] | 22.9% [10.4] | 0.04 |

| Median (50th percentile) | 23.1% | 23.1% | 23.3% | 22.9% | |

| 25th, 75th percentiles | 18.6%, 27.5% | 18.7%, 27.3% | 18.8%, 27.8% | 18.2%, 27.3% | |

|

Risk-Standardized Readmission Rate |

|||||

| Mean [SD] | 23.8% [1.3] | 23.7% [1.3] | 23.9% [1.4] | 23.8% [1.4] | <0.001 |

| Median (50th percentile) | 23.7% | 23.6% | 23.8% | 23.7% | |

| 25th, 75th percentiles | 23.0%, 24.5% | 23.0%, 24.4% | 23.1%, 24.7% | 23.0%, 24.5% | |

Note: SD=Standard Deviation.

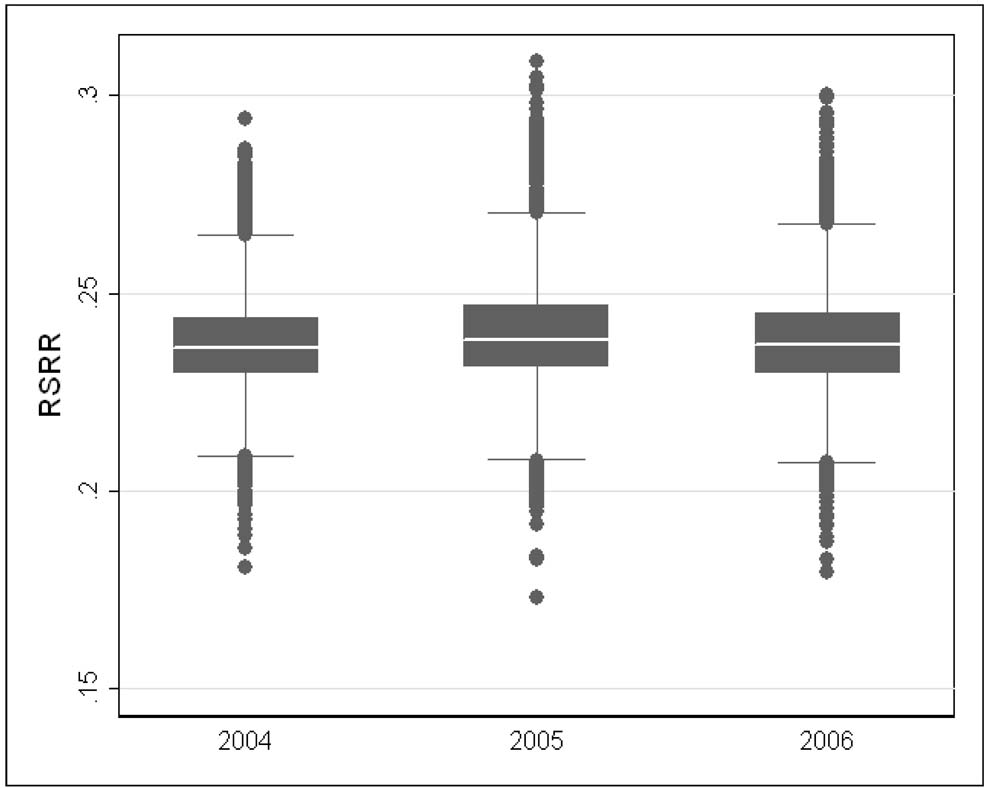

Annual estimates of between-hospital variation in patient risk of readmission were similar: 0.021 (SE=0.001) for 2004, 0.024 (SE=0.002) for 2005, and 0.025 (SE=0.002) for 2006. This implies that the odds of readmission for a patient discharged from a hospital one standard deviation above the national mean is 1.4 times that for a patient discharged from a hospital one standard deviation below the national mean. In 2004, 2005, and 2006, the mean RSRR was 23.7% (SD=1.3; Inter-quartile [IQ] range: 23.0%–24.4%), 23.9% (SD=1.3; IQ range: 23.1%–24.7%), and 23.8% (SD=1.3; IQ range: 23.0%–24.5%) (p<0.001), respectively, and there was similar heterogeneity in hospital-specific RSRRs across all three years (Figure 1). Again, although there were statistically significant differences in mean RSRRs by year, this finding was not clinically significant. Pooling all three years of data, the mean hospital-specific 30-day RSRR after HF hospitalization from 2004 through 2006 was 23.8% (SD=1.3; IQ range: 23.0%–24.5%).

Figure 1. Frequency distribution of RSRRs for fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries discharged after heart failure hospitalization, 2004–2006.

Note: The upper boundaries of the boxes represent the seventy-fifth percentile, the lines bisecting the boxes represent the median or fiftieth percentile, and the lower boundaries of the boxes represent the twenty -fifth percentile. The upper and lower boundaries of the whiskers are set at 1.5 * IQR above the seventy-fifth percentile and at 1.5 * IQR below the twenty-fifth percentile respectively, with dots representing hospitals beyond these percentiles at the extreme.

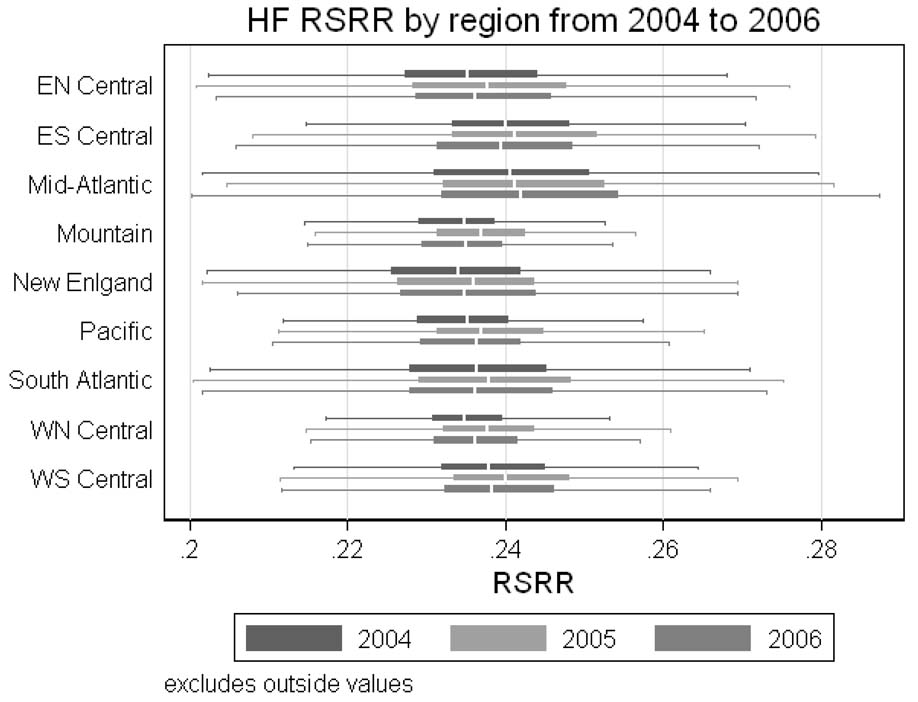

There were small statistical differences in the mean hospital-specific 30-day unadjusted and RSRRs across Census Divisions of the United States from 2004 through 2006 (p<0.001), but these differences were not clinically significant and there was also similar heterogeneity in hospital-specific 30-day RSRRs among all three years across Census Divisions (Figure 2). Hospitals in the Mountain Division were found to have the lowest mean hospital-specific RSRR (23.5%, SD=1.0; IQ range, 23.0%–24.0%), whereas hospitals in the Mid-Atlantic Division were found to have the highest mean hospital-specific RSRR (24.2%, SD=1.4; IQ range, 23.2%–25.2%).

Figure 2. Frequency distribution of RSRRs for fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries discharged after heart failure hospitalization by Census Division, 2004–2006.

Note: The left-most boundaries of the narrow boxes represent the seventy-fifth percentile, the lines bisecting the narrow boxes represent the median or fiftieth percentile, and the right-most lower boundaries of the boxes represent the twenty -fifth percentile. The left-most and right-most boundaries of the whiskers are set at 1.5 * IQR below the twenty-fifth percentile and 1.5 * IQR above the seventy-fifth percentile respectively. Hospitals beyond these percentiles at the extreme were excluded from this Figure.

DISCUSSION

Among fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries discharged alive after hospitalization for HF, we found that recent risk-standardized hospital-specific 30-day readmission rates approached 25% across the United States in each of 3 years we studied, consistent with prior estimates,9 and that there were no clinically important changes in readmission rates over this time period. Our findings demonstrate that there has been no aggregate improvement, across the nation or in any geographic region, in readmission rates after HF hospitalization. Readmitting nearly a quarter of patients after HF hospitalization within 30 days is not likely to represent optimal care for patients and suggests that there is substantial room and a clear opportunity for improvement that might be achieved through enhancing the quality of inpatient care or through improved transitions from the inpatient to the outpatient environments. Paying greater attention to hospital readmission rates through surveillance efforts such as public reporting may be an important first step towards this goal.

We found similar heterogeneity among hospital performance in all three years. Half of U.S. hospitals were found to have RSRRs within 1.5% of one another, suggesting that there is little variability in the effectiveness of hospitals’ approach to managing transitions of care among patients discharged after HF hospitalization and that all U.S. hospitals appear to be facing similar challenges in preventing readmissions. Although the lack of practice variation prohibits our exclusion of the possibility that all hospitals are functioning at peak efficiency and are providing transition care of the highest quality, several clinical interventions have been shown to lower readmission rates below usual care. We cannot determine whether all the patients discharged after HF hospitalization were consistently provided with necessary services and medications, or whether they were taught how to manage their health and monitor their symptoms, or they had an appointment scheduled with their primary care physician, who had received necessary and critical information about the patient’s hospitalization, to ease the transition from the hospital to home. However, each of these actions represents a previously identified strategy to minimize hospital readmissions after HF hospitalization that ideally would be widely used and are likely to lower readmission rates within 30 days below 25%.13, 14, 18, 19, 21, 22 Despite randomized, controlled trials of post-discharge HF disease management repeatedly demonstrating patient benefits and reduced costs,14–16, 22 practices proven to be effective in U.S. studies have generally not been continued or expanded, mostly because of financial constraints, whereas similar practices proven to be effective in other countries have often become permanent.25

We hypothesize that the hospital performance we have observed is likely to be a function of the current fee-for-service payment system and future research is needed to examine readmission rates in health systems that do not use a fee-for-service payment system, such as the Veterans Health Administration. Rather than rewarding better outcomes, current CMS hospital and physician payment policy rewards greater volume. Piecemeal payment is an economic incentive for health care providers, both hospitals and physicians, to increase patient volume and service intensity during hospitalizations in order to increase revenue. In contrast, CMS payments are low or do not exist for the services that have been proven to lower hospitalization rates, such as disease management strategies. Appropriate delivery of these services may potentially reduce hospitalization revenue substantially without creating reciprocal revenue elsewhere, even if hospitals offer extensive ambulatory care services, which would in turn impede hospitals and physician groups from adopting such strategies.25 Fortunately, MEDPAC recently recommended that CMS alter its payment policy and re-align financial incentives, driving collaborations and clinical integration between hospitals, physicians, nurses, and other outpatient services by bundling payments around a hospitalization.3 Action needs to be taken to ensure that these reforms are enacted and financial incentives are established to improve transition care quality, thereby lowering readmission rates.

Public reporting of hospital readmission rates offers an important opportunity to provide a visible incentive for health care quality improvement by promoting informed patient choices, fostering hospital concern for protecting or enhancing its public image, and providing objective feedback that fuels professional desires to improve care.26–28 At the very least, ongoing public reporting efforts by CMS can be used to inform practice and policy, rather than being isolated from them as in the past,25 to identify high quality hospitals that can be subsequently examined in an effort to determine which structures and processes of care enable and sustain the provision of high quality care or low quality hospitals whose performance can be subsequently addressed.

Our study is among the first to describe national estimates of hospital-specific 30-day all-cause readmission rates after HF hospitalization, using a risk-standardization model to determine hospital performance that was endorsed by the National Quality Forum and validated using chart-abstracted data. However, there are considerations in interpreting our results. First, we examined readmission outcomes only for patients who had been discharged after hospitalization for HF, so that our results may not be generalized to other conditions. However, HF is among the most common hospital discharge diagnoses and readmission after HF hospitalization has been shown to be modifiable through controlled interventions, justifying our focus on the condition. Second, we only examined readmission outcomes for HF patients and did not address other important dimensions of quality, such as mortality, processes of care, health status outcomes or other patient care experiences, such as treatment satisfaction. Third, although our study provides insights for understanding health care delivery in the United States, it was limited to fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries and the hospital readmission rates we estimated using this population may not be representative of the readmission rates of other populations. Finally, because of Medicare data availability, we only report on readmission trends through 2006. We are unable to determine whether other recent efforts outside of CMS to lower hospital readmission rates, such as the focus on readmission rates by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, have had an impact over the past 2 years.

In conclusion, there has been no recent national or regional improvement in hospital readmission care among Medicare beneficiaries discharged alive after HF hospitalization. Recent national hospital-specific risk-standardized readmission rates approached 25% for the most common discharge diagnosis among Medicare beneficiaries and the distribution in hospital performance has not changed. Given the need to lower readmission rates, it is hoped that the upcoming efforts by CMS to publicly report HF RSRRs for all hospitals can offer an important opportunity to drive health care quality improvement.

Acknowledgment

Funding/support and role of the sponsor: The analyses upon which this publication is based were performed under Contract Number HHSM-500-2005-CO001C, entitled "Utilization and Quality Control Quality Improvement Organization for the State (commonwealth) of Colorado,” funded by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, an agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The authors assume full responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the ideas presented. Dr. Ross is currently supported by the National Institute on Aging (K08 AG032886) and by the American Federation of Aging Research through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program. Dr. Bueno was supported by Grant #BA08/90010 from the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain. Dr. Vidán was supported by Grant #BA08/90012 from the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain.

Footnotes

Data access and responsibility: Dr. Ross had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflicts of interest: Drs. Chen, Lin, Curtis, Normand, Wang, Wang, and Krumholz and Mr. Schreiner report that they developed RSRRs for heart failure under contract with the Colorado Foundation for Medical Care. Dr. Krumholz reports that he chairs a scientific advisory board for UnitedHealthcare.

Author contributions: Drs. Ross and Krumholz were responsible for the conception and design of this work. Dr. Ross drafted the manuscript. Dr. Krumholz obtained funding and provided supervision. All authors participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. Dr. Lin conducted the statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services Hospital Pay-for-Performance Workgroup. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Medicare Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Plan Development, Issues Paper, 1st Public Listening Session. [Accessed October 27, 2008];Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. 2007 January 17; Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/AcuteInpatientPPS/Downloads/Hospital_VBP_Plan_Issues_Paper.pdf.

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Rewarding provider performance: aligning incentives in Medicare. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Promoting greater efficiency in Medicare, report to the Congress. [Accessed July 17, 2007];Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/documents/Jun07_EntireReport.pdf.

- 4.National Quality Forum. National Voluntary Consensus Standards for Hospital Care 2007: Performance Measures -- A consensus report. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krumholz HM, Brindis RG, Brush JE, Cohen DJ, Epstein AJ, Furie K, Howard G, Peterson ED, Rathore SS, Smith SC, Jr, Spertus JA, Wang Y, Normand SL. Standards for statistical models used for public reporting of health outcomes: an American Heart Association Scientific Statement from the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Writing Group: cosponsored by the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention and the Stroke Council. Endorsed by the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2006;113(3):456–462. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.170769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krumholz HM, Keenan PS, Brush JE, Jr, Bufalino VJ, Chernew ME, Epstein AJ, Heidenreich PA, Ho V, Masoudi FA, Matchar DB, Normand SL, Rumsfeld JS, Schuur JD, Smith SC, Jr, Spertus JA, Walsh MN. Standards for Measures Used for Public Reporting of Efficiency in Health Care. A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2008 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.190500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merrill CT, Elixhauser A. Hospitalization in the United States, 2002. HCUP Fact Book No. 6. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005. AHRQ Publication No. 05-0056. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keenan PS, Normand SL, Lin Z, Drye EE, Bhat KR, Ross JS, Schuur JD, Stauffer BD, Bernheim SM, Epstein AJ, Wang Y, Herrin J, Chen J, Federer JJ, Mattera JA, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. An administrative claims measure suitable for profiling hospital performance on the basis of 30-day all-cause readmission rates among patients with heart failure. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2008;1(1):29–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.802686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krumholz HM, Parent EM, Tu N, Vaccarino V, Wang Y, Radford MJ, Hennen J. Readmission after hospitalization for congestive heart failure among Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(1):99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashton CM, DelJunco DJ, Souchek J, Wray NP, Mansyur CL. The association between the quality of inpatient care and early readmission - A meta-analysis of the evidence. Med. Care. 1997;35(10):1044–1059. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199710000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gwadry-Sridhar FH, Flintoft V, Lee DS, Lee H, Guyatt GH. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing readmission rates and mortality rates in patients with heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(21):2315–2320. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.21.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lappe JM, Muhlestein JB, Lappe DL, Badger RS, Bair TL, Brockman R, French TK, Hofmann LC, Horne BD, Kralick-Goldberg S, Nicponski N, Orton JA, Pearson RR, Renlund DG, Rimmasch H, Roberts C, Anderson JL. Improvements in 1-year cardiovascular clinical outcomes associated with a hospital-based discharge medication program. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(6):446–453. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-6-200409210-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillips CO, Wright SM, Kern DE, Singa RM, Shepperd S, Rubin HR. Comprehensive discharge planning with postdischarge support for older patients with congestive heart failure: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;291(11):1358–1367. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.11.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jovicic A, Holroyd-Leduc JM, Straus SE. Effects of self-management intervention on health outcomes of patients with heart failure: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2006;6:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-6-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McAlister FA, Lawson FM, Teo KK, Armstrong PW. A systematic review of randomized trials of disease management programs in heart failure. Am J Med. 2001;110(5):378–384. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00743-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonseth J, Guallar-Castillon P, Banegas JR, Rodriguez-Artalejo F. The effectiveness of management programmes in reducing hospital re-admission in older patients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published reports. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(18):1570–1595. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, Leven CL, Freedland KE, Carney RM. A Multidisciplinary Intervention to Prevent the Readmission of Elderly Patients with Congestive-Heart-Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333(18):1190–1195. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider JK, Hornberger S, Booker J, Davis A, Kralicek R. A medication discharge planning program: measuring the effect on readmissions. Clin Nurs Res. 1993;2(1):41–53. doi: 10.1177/105477389300200105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart S, Pearson S, Horowitz JD. Effects of a home-based intervention among patients with congestive heart failure discharged from acute hospital care. Arch. Intern. Med. 1998;158(10):1067–1072. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.10.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koelling TM, Johnson ML, Cody RJ, Aaronson KD. Discharge education improves clinical outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2005;111(2):179–185. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151811.53450.B8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krumholz HM, Amatruda J, Smith GL, Mattera JA, Roumanis SA, Radford MJ, Crombie P, Vaccarino V. Randomized trial of an education and support intervention to prevent readmission of patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(1):83–89. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01699-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pope GC, Kautter J, Ellis RP, Ash AS, Ayanian JZ, Lezzoni LI, Ingber MJ, Levy JM, Robst J. Risk adjustment of Medicare capitation payments using the CMS-HCC model. Health Care Financ Rev. 2004;25(4):119–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Normand SL, Zou KH. Sample size considerations in observational health care quality studies. Stat Med. 2002;21(3):331–345. doi: 10.1002/sim.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seow H, Phillips CO, Rich MW, Spertus JA, Krumholz HM, Lynn J. Isolation of health services research from practice and policy: the example of chronic heart failure management. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(3):535–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Devers KJ, Pham HH, Liu G. What is driving hospitals' patient-safety efforts? Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23(2):103–115. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.2.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Tusler M. Does publicizing hospital performance stimulate quality improvement efforts? Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;22(2):84–94. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.2.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Tusler M. Hospital performance reports: impact on quality, share, and reputation. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(4):1150–1160. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.4.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]