It is widely accepted that poor breathing technique on any wind instrument breaks up the shape and flow of a solo. To overcome this problem, woodwind instrument players—especially saxophonists—often use circular breathing techniques (fig 1) to produce seamless air streams, inhaling through the nose while simultaneously inflating the cheeks and neck with air. This is a demanding and possibly dangerous exercise.1 Despite anecdotal reports of death by cerebrovascular causes,2,3 there has been no formal study looking at mortality in these musicians.

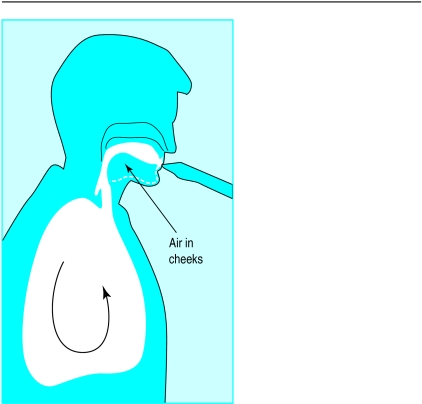

Figure 1.

Circular breathing. Intake of breath fills the chest and stomach; cheeks and neck are inflated when air is halfway up the chest. While forcing air from cheeks and neck into the instrument, the player simultaneously breathes in through the nose to the bottom of the stomach

Subjects, methods, and results

Two compendiums of jazz with information on famous jazz musicians were used as the source of the cohort.2,3 Information retrieved included dates of birth and death (where relevant), nationality (American or otherwise), number and type of main instrument played (voice, brass, woodwind, percussion, keyboards, string), saxophone (played or not), social class (number of hit albums), social cohesion (number of band members), and having control over life situations (being band leader). Association between the variables and mortality was examined by Cox proportional hazards models using Stata version 5. Year of birth was divided into fifths to control for secular trends.

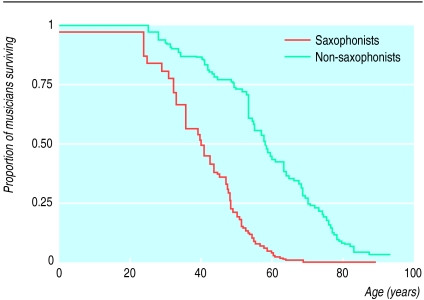

In total, 813 musicians born between 1 January 1882 and 30 June 1974 were identified, providing 49 360 person years to the analysis. Of these, 349 (43%) died during the follow up period (to 15 February 1998, the most recent date of book publication). Saxophone players were more at risk of death than other musicians (fig 2). Other variables that were significantly associated with mortality risk were US nationality, playing more than one instrument, and being bandleader (table). Of the instrument groups, only brass and woodwind were associated with significantly higher mortality (compared with vocalists).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of saxophonists and other instrumentalists

Comment

Among famous jazz musicians, playing saxophone is a major health hazard. Other factors associated with higher mortality include, to a smaller extent, playing other woodwind instruments or being of US nationality. Playing more than one instrument or being a bandleader has a protective influence.

There is some possibility of misclassification bias as the instruments used to measure social class, social cohesion, and control over life situations have not been used before. However, these measures went through extensive validation procedures: 100% of the authors' friends who were asked their opinions on these measures agreed that they were a “good” or a “very good” idea. Another possible limitation of our study is that some factors related to mortality (smoking and alcohol intake, for example) were not controlled for. Smoky bars would ensure that all jazz musicians would be exposed to similar levels of smoke, making smoking an unlikely confounder. Further research is, however, needed in this area: it is anticipated that attendance at a number of national and international concert venues would resolve this issue, and the researchers are currently seeking funding for this.

The observed association between woodwind players, especially saxophonists, and mortality has a plausible biological explanation. Raised pressure in the neck region can increase mortality either by reducing blood supply to the brain (cerebrovascular ischaemia) or venous stasis (thromboembolism). This theory is strengthened by the observation of a dose-response effect whereby the saxophonists and other woodwind instrument players, with maximum and intermediate likelihood of circular breathing respectively, are correspondingly ranked in the levels of mortality. The results need to be interpreted with caution, as circular breathing was not measured directly.

This study has important public health implications for jazz saxophonists as it identifies important modifiable behavioural factors. Health promotion campaigns encouraging saxophonists to play more than one instrument or to declare themselves as leaders of their bands should have a significant impact on their mortality.

To conclude, in the words of famous jazz saxophonist Sonny Rollins: “Sometimes when I am in the midst of really good performance, my mind will imperceptibly switch to automatic pilot and I find myself just standing there while the spirit of jazz, as it were, occupies my body, choosing for me the correct note, the correct phrase, the correct idea and when to play it. It is a profound spiritual experience!”1 Spiritual experienceor cerebrovascular ischaemia—who knows?

Figure.

BETTMANN/CORBIS

John “Trane” Coltrane (1926-67), more than any other player, legitimised the extended jazz solo. Addicted to drugs and alcohol, he died of liver failure

Table.

Relative mortality in 813 musicians born between 1882 and 1974

| Explanatory variable | No of subjects | No of deaths | Crude hazard ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted hazard ratio* (95% Cl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Play saxophone (yes) | 230 | 136 | 1.84 (1.48 to 2.28) | 2.47 (1.89 to 3.24) |

| Play more than one instrument (yes) | 367 | 134 | 0.76 (0.61 to 0.94) | 0.53 (0.40 to 0.70) |

| Nationality (American) | 550 | 292 | 1.90 (1.43 to 2.53) | 1.79 (1.29 to 2.50) |

| Control over life situations (yes) | 231 | 83 | 0.64 (0.50 to 0.83) | 0.71 (0.55 to 0.92) |

| Social class† (higher) | 633 | 262 | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.02) | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.02) |

| Social cohesion† (greater) | 633 | 262 | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.04) |

| Main instrument group‡: | ||||

| Vocalist | 54 | 18 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Brass | 161 | 80 | 1.53 (0.91 to 2.54) | 2.03 (1.11 to 3.72) |

| Woodwind | 219 | 109 | 1.70 (1.03 to 2.80) | 2.09 (1.15 to 3.78) |

| Percussion | 113 | 39 | 1.12 (0.63 to 1.94) | 1.33 (0.70 to 2.53) |

| Keyboard | 138 | 59 | 1.56 (0.92 to 2.65) | 1.59 (0.94 to 2.71) |

| String | 128 | 44 | 1.34 (0.77 to 2.32) | 1.69 (0.90 to 3.18) |

Adjusted for other remaining variables in table.

Used as continuous variable; all others used as binary variables (yes/no).

Other instrument groups compared with vocalist as baseline.

Figure.

AP PHOTO

Charlie “Bird” Parker (1920-55) is widely regarded as the messiah of modern jazz; on his death (of lobar pneumonia), graffiti artists scrawled “Bird lives!” in the New York subways

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all those famous jazz musicians who laid down their lives for the sake of a long-drawn solo.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: SK loves jazz, MO doesn't care; hence there is no competition of interests.

References

- 1.Fordham J. Jazz. London: Dorling Kindersley; 1993. An anatomy of instruments; pp. 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cook R, Morton B, editors. The Penguin guide to jazz. London: Penguin Books; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carr I, Fairweather D, Priestley B, editors. Jazz: the rough guide. London: Penguin Books; 1998. [Google Scholar]