Abstract

Objective

This study examined the clinical significance of loss of control over eating (LOC) in bariatric surgery over 24 months of prospective multi-wave follow-ups.

Method

Three-hundred sixty-one gastric bypass surgery patients completed a battery of assessments before surgery and at 6, 12, and 24 months following surgery. In addition to weight loss and LOC, the assessments targeted eating disorder psychopathology, depression levels, and quality of life.

Results

Prior to surgery, 61% of patients reported LOC; post-surgery, 31% reported LOC at 6-month follow-up, 36 % reported LOC at 12-month follow-up, and 39% reported LOC at 24-month follow-up. Preoperative LOC did not predict post-operative outcomes. In contrast, mixed models analyses revealed that post-surgery LOC was predictive of weight loss outcomes: patients with LOC post-surgery lost significantly less weight at 12-month (34.6 vs. 37.2% BMI loss) and 24-month (35.8 % vs. 39.1 % BMI loss) post-surgery follow-ups. Similarly, post-surgery LOC significantly predicted eating-disorder psychopathology, depression, and quality of life at 12- and 24-month post-surgery follow-ups.

Conclusions

Pre-operative LOC does not appear to be a negative prognostic indicator for post-surgical outcomes. Postoperative LOC, however, is a prospective predictor of significantly poorer post-surgical weight and psychosocial outcomes at 12- and 24- month following surgery. Since LOC following bariatric surgery significantly predicts attenuated post-surgical improvements, it represents an important target for clinical attention.

Keywords: Obesity, weight loss surgery, binge eating, loss of control over eating

Bariatric surgery is the most effective treatment for severe obesity, yielding average losses of approximately 35% of initial body weight 1. Despite the rapid and dramatic weight loss that is achieved in the initial months post-surgery, the loss begins to plateau and is frequently followed by weight regain in the 2 to 10 years following surgery 2. Similarly, research has documented substantial improvements in psychosocial functioning following bariatric surgery although the longer-term durability of these improvements is less certain 3. Since a substantial proportion of patients begin to re-gain weight and some patients fail to benefit psychosocially 4, several lines of research have attempted to identify patient variables that may predict long-term treatment outcome 5. To date, few psychosocial factors have emerged as reliable predictors of either weight loss or psychosocial functioning following bariatric surgery5. For example, research has found that clinically hypothesized variables such as preoperative depression 6 and history of prior sexual abuse or childhood maltreatment 7 do not prospectively predict short-term (e.g., 12-month) bariatric surgery outcomes.

As broad psychosocial factors have not emerged as reliable predictors, interest in eating-specific behaviors has grown 5. In fact, considerable research attention has been devoted to whether binge eating confers a poor prognosis 8 as binge eating behaviors 9–11 and binge eating disorder (BED) 12, 13 are common in bariatric surgery candidates. Binge eating is defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR; 14) as eating an usually large amount of food while experiencing a subjective sense of loss of control over the eating. Pre-surgery, patients who binge eat do not differ in weight status 15 from non-binge eating patients, but are generally characterized by greater psychosocial problems 10, 16–18 and significantly greater psychiatric comorbidity 13.

Research on the prognostic significance of preoperative binge eating on bariatric surgery outcomes has focused mostly on changes in weight. To date, findings regarding the prognostic significance of preoperative binge eating are mixed, with some reports of baseline binge eating predicting less weight loss 19, 20, while others report the opposite pattern 21 or no relationship 17, 22. In terms of psychosocial functioning outcomes, Malone and Alger-Mayer 23 reported that patients with more severe binge eating problems before surgery benefited the most in terms of improved quality of life post-surgery. In contrast, Green and colleagues 24 reported that although binge eaters reported heightened depression and deflated self-esteem pre-surgically, they did not differ from those who did not report preoperative binge eating at 6-months post-surgery. Most recently, White et al. 11 reported that patients with preoperative binge eating improved substantially at 12 months post-surgery in all domains measured, including weight loss and global psychosocial functioning. At 12-months post-surgery, none of the patients reported binge eating at the diagnostic threshold frequency specified by the DSM-IV-TR for BED; 8.8% reported infrequent binge eating (i.e., less than once per week) and only one patient (0.7%) reported binge eating weekly. These substantial improvements in binge eating support previous reports of a near remission of binge eating symptoms following surgery 17, 25, 26.

It is important to emphasize that following surgery, binge eating – traditionally defined as eating unusually large amounts of food – may not be physically possible. Indeed, consumption of either too-large portions or rich or high-fat foods following bariatric surgery typically results in vomiting and/or dumping syndrome. These unpleasant events would likely occur before, and effectively prevent (or greatly reduce frequency of), the consumption of an objectively large amount of food. Although binge eating may be physically impossible following surgery, a different facet of binge eating pathology may remain or emerge postoperatively. Specifically, the subjective sense of loss of control (LOC) over eating may be an important indicator of eating problems postoperatively. Indeed, recent research with diverse clinical and community groups across all weight categories has suggested that the presence of LOC – regardless of the amount of food consumed – is clinically meaningful. Eating with LOC (over small or subjectively large amounts of food) generally involves more calories and a higher percentage of fat and carbohydrate intake 27, 28 and predicts eating disorder psychopathology 29, 30 and psychological disturbance 31 in a manner similar to LOC over objectively large amounts of food. Preliminary research with bariatric surgery patients suggests that LOC may be especially relevant. Kalarchian et al. 32, in a cross-sectional study of 99 bariatric surgery patients, found that patients reporting postoperative LOC had less successful weight outcomes than those reporting no LOC. Unfortunately conclusions from this study are limited by the cross-sectional design. A recent longitudinal report of 129 bariatric patients followed for 12 months after surgery found that LOC over eating was common following surgery, and was associated with poorer weight and psychosocial outcomes 33.

The present study examined the clinical significance of LOC in a large series of bariatric surgery patients over 24 months of prospective multi-wave follow-ups. Patients were assessed pre-operatively and then re-assessed post-surgery at 6-, 12- and 24-month follow-ups. This design allowed for consideration of both pre-surgery and post-surgery LOC as concurrent and prospective predictors of weight loss and psychosocial functioning. Specific hypotheses were: 1) preoperative LOC would predict postoperative LOC, 2) Patients with and without preoperative LOC would differ in BMI and psychosocial domains, 3) Postoperative LOC would be a function of preoperative LOC and length of time since surgery, 4) Weight loss would be a function of preoperative and postoperative LOC, and time, and 5) LOC would predict psychosocial outcomes.

Method

Participants

Participants were 361 (50 male and 311 female) extremely obese patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery at two general medical centers in the Northeast United States. Mean age was 43.7 years (SD=10.0) and mean body mass index (BMI) was 51.1 (SD=8.3). Of the participants, 81.4% (N=294) were Caucasian, 9.1% (N=33) were African American, 7.2% (N=26) were Hispanic American, 0.3% (N=1) was Asian, and 2.0% (N=7) were of other ethnicity or unknown. Educationally, 67.9% (N=245) attended at least some college and an additional 26.3% (N=95) completed high school. The two sites did not differ in BMI, distribution of gender, or educational attainment.

Informed Consent and Study Procedures

IRB approval was granted at each site, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Patients were informed that they were participating in research studies to learn about the effects of bariatric surgery over time on weight, eating behaviors, psychological functioning, and general quality of life. Patients were informed that their participation would not influence the type of care provided by the surgical team. Patients were told there would be no direct medical benefit to them, although it was hoped that the knowledge gained might ultimately benefit other bariatric patients in the future. Patients were also informed that the findings would only be shared with the treatment team if they so desired and provided consent. No compensation was provided.

Patients completed a battery of assessments prior to surgery, and at 6-month, 12-month, and 24-month follow-up points. Of the patients who completed the baseline (pre-operative) assessment, 86.1% (N=311) completed the 6-month follow-up, 81.4% (N=294) completed the 12-month follow-up, and 47.4% (N=171) completed the 24-month follow-up. In order to be included in the current study, participants had to have completed at least one follow-up assessment. ‡

Measures

Weight Self-report

Percent weight loss from baseline was the primary outcome variable. BMI (weight in kilograms / height in meters-squared) was calculated from self-reported weight and height, as part of a larger questionnaire battery and completed at the same time as the psychosocial measures. Concurrently measured (i.e., by clinic staff) weight data were available for a subsample (n=187). In this subsample, the measured (M=51.9, sd=7.9) and self-reported (M=51.7, sd=8.4) BMIs did not differ (t(186)=.75, p=.46). Further, the degree of misreport was unrelated to increasing BMI (r (185)=.12, p=.11).

Assessment of features of eating disorders and loss of control

The Eating Disorder Examination – Questionnaire (EDE-Q)34, the self-report version of the Eating Disorder Examination Interview35, assesses eating disorder psychopathology. The EDE-Q assesses the frequency of various forms of overeating, including binge eating. The EDE-Q comprises four subscales (dietary restraint, eating concerns, weight concerns, and shape concerns) and yields a global score. Items are rated on seven point scales (0 to 6), with higher scores reflecting greater severity or frequency. Most items are specific to current symptomatology, encompassing the previous 28-day period. LOC was defined as the presence or absence of any LOC episodes in the previous 28 day period. This assessment method for LOC follows that previously used in studies with diverse clinical groups 29, 30, 32. Both objective bulimic episodes (OBE; defined as eating unusually large amounts of food while experiencing a subjective sense of loss of control) and subjective bulimic episodes (SBEs; defined as experiencing loss of control when eating small or normal amounts of food) were classified as LOC episodes. The EDE-Q has received psychometric support, including adequate test-retest reliability 36 and good convergence with the EDE Interview 34, 37–41. Further, the EDE-Q has been shown to adequately identify binge eating in bariatric surgery candidates 10, 42.

Assessment of psychological functioning

The Beck Depression Inventory

(BDI) 43 21-item version assesses current depression level and symptoms of depression. It is a widely used and established measure with demonstrated reliability and validity 44. Higher scores on the BDI reflect higher levels of depression and, more broadly, negative affect 45, 46; higher scores are also an efficient marker for heightened psychopathological and psychiatric disturbances 46.

The Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-36 Health Survey

(SF-36) 47 is a 36-item, widely used, self-report instrument to assess health-related quality of life (HRQL). The SF-36 has well-established reliability 48 and validity 49. The instrument comprises 8 subscales: Physical Functioning, Physical Role Limitation, Bodily Pain, General Health, Vitality, Social Functioning, Emotional Role Limitation, and Mental Health. Each subscale is composed of frequency (e.g., 6-point scale from 1 [all of the time] to 6 [none of the time]), severity (e.g., 3-point scale from 1 [yes, limited a lot] to 3 [no, not limited at all]), or forced choice (e.g., 2-point scale for yes or no) items. The SF-36 raw scale scores are transformed to scores ranging from 0 (lowest level of HRQL) to 100 (highest level of HRQL) with a standard deviation of 15 50. The SF-36 also generates 2 summary scores: the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and the Mental Component Summary (MCS) 51. The PCS and MCS scores are such that the means are 50 and standard deviations are 10 for the general US population.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using SAS v9.1 and SPSS v14.0. One-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to test the hypothesis that pre-surgery LOC groups would differ on BMI and psychosocial outcomes at baseline. A series of binary logistic regression analyses was used to test the hypothesis that timepoint-specific post-operative LOC would be predicted by LOC at baseline. To test the hypothesis that post-operative LOC would be a function of pre-operative LOC and the time-since-surgery, data were analyzed using nonlinear mixed models for binary outcomes. Finally, mixed effects regression analyses were used to test the hypotheses that weight and psychosocial outcomes would be predicted by baseline LOC, postoperative LOC, time-since-surgery, and their interactions.

Results

Baseline characteristics

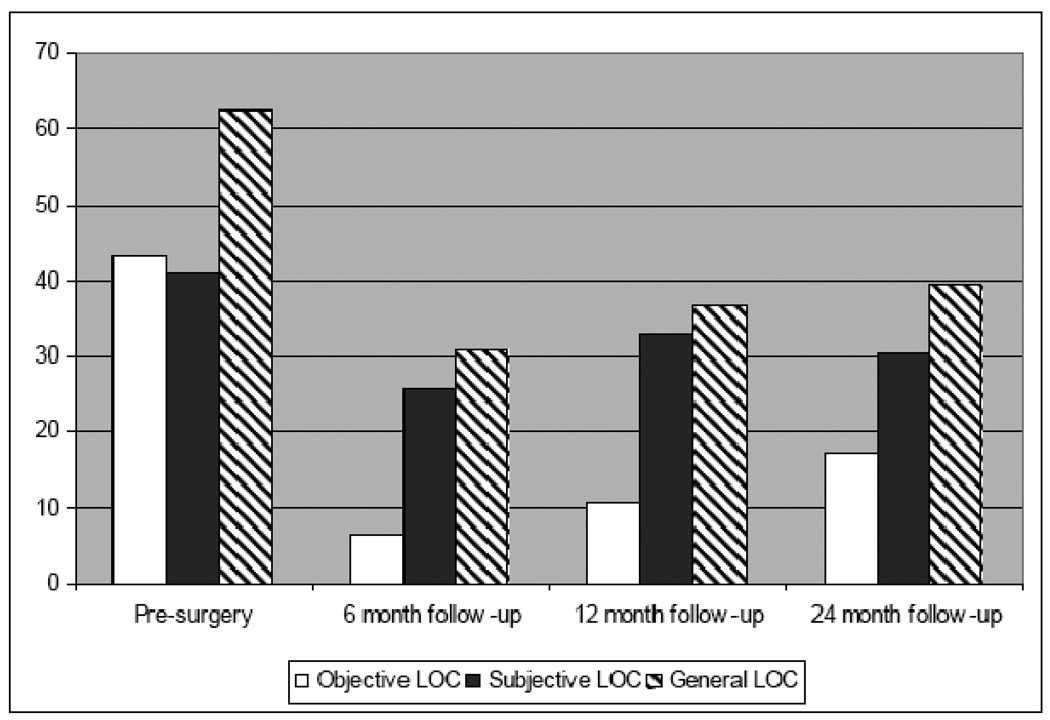

Prior to surgery, 42.4% (N=153) of patients reported LOC for objectively large eating episodes, 40.2% (N=145) reported LOC for small episodes, and 61.2% (N=221) reported general LOC (i.e., loss of control for either large or small amounts of food). Odds ratios were generated to determine whether LOC for small and large eating episodes at baseline were related. Analyses revealed that individuals reporting LOC over small episodes were twice as likely to report LOC over large eating episodes (OR=2.1, Wald=11.15, p= .001; 95% CI = 1.4 – 3.2).

Hypothesis 1

Preoperative LOC would predict postoperative LOC

The hypothesis that postoperative LOC would be predicted by preoperative LOC was tested using simple binary logistic regression analyses for each follow-up time point. In this series of analyses, baseline LOC for both objectively large episodes as well as general loss of control (i.e., for both large and small amounts of food) was considered. Point prevalence and test statistics are presented in Table 1. As shown in the table, either type of baseline LOC is highly predictive of LOC post-surgery. Therefore, general LOC (for either small or large episodes) at baseline was considered as the primary variable for the remainder of the analyses.

Table 1.

Point prevalence of post-surgical Loss-of-Control over eating episodes as a function of preoperative loss-of-control.

| 6 months LOC % of sample (N) |

12 Months LOC % (N) |

24 months LOC % (N) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Present | Absent | Present | Absent | Present | Absent |

| No Objective LOC (large episodes) |

22.4 (38) | 77.6 (132) | 28.1 (47) | 71.9 (120) | 33.7 (30) | 66.3 (59) |

| Objective LOC (large episodes) |

41.5 (54) | 58.5 (76) | 49.6 (57) | 50.4 (58) | 46.2 (36) | 53.8 (42) |

| Total | 30.7 (92) | 69.3 (208) | 36.9 (104) | 63.1 (178) | 39.5 (66) | 60.5 (101) |

| Wald=12.4, p<.001; | Wald=13.1, p<.001; | Wald = 2.68, p=.102; | ||||

| Exp(B)=2.47 | Exp(B)=2.51 | Exp(B)=1.69 | ||||

| Present | Absent | Present | Absent | Present | Absent | |

| No Subjective LOC (small episodes) |

23.7 (41) | 76.3 (132) | 29.4 (50) | 70.6 (120) | 31.4 (32) | 68.6 (70) |

| Subjective LOC (small episodes) |

40.6 (52) | 59.4 (76) | 47.4 (54) | 52.6 (60) | 52.5 (34) | 48.5 (32) |

| Total | 30.9 (93) | 69.1 (208) | 36.6 (104) | 63.4 (180) | 39.3 (66) | 60.7 (102) |

| Wald=9.7, p=.002; | Wald=9.34, p=.002; | Wald=6.70, p=.010; | ||||

| Exp(B)=2.20 | Exp(B)=2.16 | Exp(B)=2.32 | ||||

| Present | Absent | Present | Absent | Present | Absent | |

| No LOC | 17.3 (19) | 82.7 (91) | 23.0 (36) | 77.0 (87) | 24.2 (16) | 75.8 (50) |

| LOC-general † | 38.4 (73) | 61.6 (117) | 45.3 (77) | 54.7 (93) | 49.0 (50) | 51.0 (52) |

| Total | 30.7 (92) | 69.3 (208) | 36.4 (103) | 63.6 (180) | 39.3 (66) | 60.7 (102) |

| Wald = 14.0, p<.001; | Wald = 14.1, p<.001; | Wald = 9.94, p=.002; | ||||

| Exp(B) = 2.99 | Exp(B) = 2.77 | Exp(B)=3.00 | ||||

Note. Percentages reflect number reporting LOC at follow-up as a proportion of baseline subgroup (LOC vs no-LOC).

General = Objective (large) or Subjective (small) bulimic episodes.

Hypothesis 2

Patients with and without preoperative LOC would differ in BMI and psychosocial domains

Baseline values for BMI and psychosocial outcomes appear in Table 2; patients with and without LOC at baseline were compared on BMI and psychosocial outcomes with one-way ANOVAs. The groups did not differ in terms of pre-surgical BMI. Significant differences were observed such that the group experiencing LOC reporting significantly higher levels of depressive symptoms, diminished quality of life as measured by the SF-36, and greater eating, shape, and weight concerns.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of sample as a function of pre-operative LOC

|

No Pre- operative LOC (N=131) |

Pre-operative LOC (N=221) |

Total | F | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||

| BMI | 52.0 | (8.5) | 50.5 | (8.3) | 51.1 | (8.4) | 2.39 | .123 |

| BDI | 11.1 | (8.0) | 17.1 | (9.7) | 14.9 | (9.5) | 35.82 | .000 |

| SF36-MCS | 49.5 | (11.2) | 44.6 | (10.8) | 46.4 | (11.2) | 16.19 | .000 |

| SF36-PCS | 33.9 | (11.0) | 30.8 | (9.3) | 31.9 | (10.1) | 8.02 | .005 |

| EDEQ Restraint | 2.4 | (1.4) | 2.4 | (1.4) | 2.4 | (1.4) | .13 | .714 |

| EDEQ Eating Concerns | 1.2 | (1.0) | 2.5 | (1.2) | 2.0 | (1.3) | 106.43 | .000 |

| EDEQ Shape Concerns | 3.8 | (1.2) | 4.6 | (1.0) | 4.3 | (1.2) | 44.99 | .000 |

| EDEQ Weight Concerns | 3.1 | (1.1) | 3.9 | (1.1) | 3.6 | (1.1) | 46.40 | .000 |

| EDEQ Total | 2.6 | (0.9) | 3.4 | (0.9) | 3.1 | (1.0) | 59.38 | .000 |

Hypothesis 3

Postoperative LOC would be a function of preoperative LOC and length of time since surgery

The point prevalence of LOC at each assessment point is presented graphically in Figure 1. Although the proportion of the sample reporting general LOC decreased immediately following surgery (χ2 (N=307, df=1)=129.5, p<.001), the prevalence of post-operative LOC increased with each follow-up point. A chi-square goodness-of-fit test found that compared to the 6-month point, the prevalence of LOC was significantly greater at 12-months (χ2 (N=289, df=1)=4.52, p=.03) and at 24-months (χ2 (N=170, df=1)=5.67, p=.02) following surgery. The difference in prevalence between the 12-month to 24-month assessment was not significant, (χ2 (N=170, df=1)=.546, p=.46). The hypothesis that postoperative LOC would be a function of pre-operative LOC and the assessment point (i.e., time interval) post surgery was tested using a nonlinear mixed model analysis (PROC NLMIXED) with a random intercept. Models were tested in which session was left as a continuous variable and included along with logarithmic, cubic, exponential, and quadratic transformation of time. Of these, the logarithmic transformation yielded the best model fit statistics. Models were tested including pre-operative LOC status, session, and the interactions. Through model-building, non-significant (p>.10) interaction terms were dropped, to yield a final model in which only the main effects significantly predicted post-operative LOC. The final model indicated that pre-operative LOC significantly predicted post-operative LOC (β=1.43, t=5.09, p=.0001). Further, the coefficient for the time effect was significant (β=0.36, t=2.03, p=.04), indicating that as the length of time between surgery and assessment increased, the likelihood of reporting LOC also increased. The intraclass correlation coefficient was highly significant (ICC=0.40, p<.0001) indicating a substantial amount of variance attributable to the subject effect.

Figure 1.

Point Prevalence of Loss of Control

Hypothesis 4

Weight loss would be a function of preoperative and postoperative LOC, and time

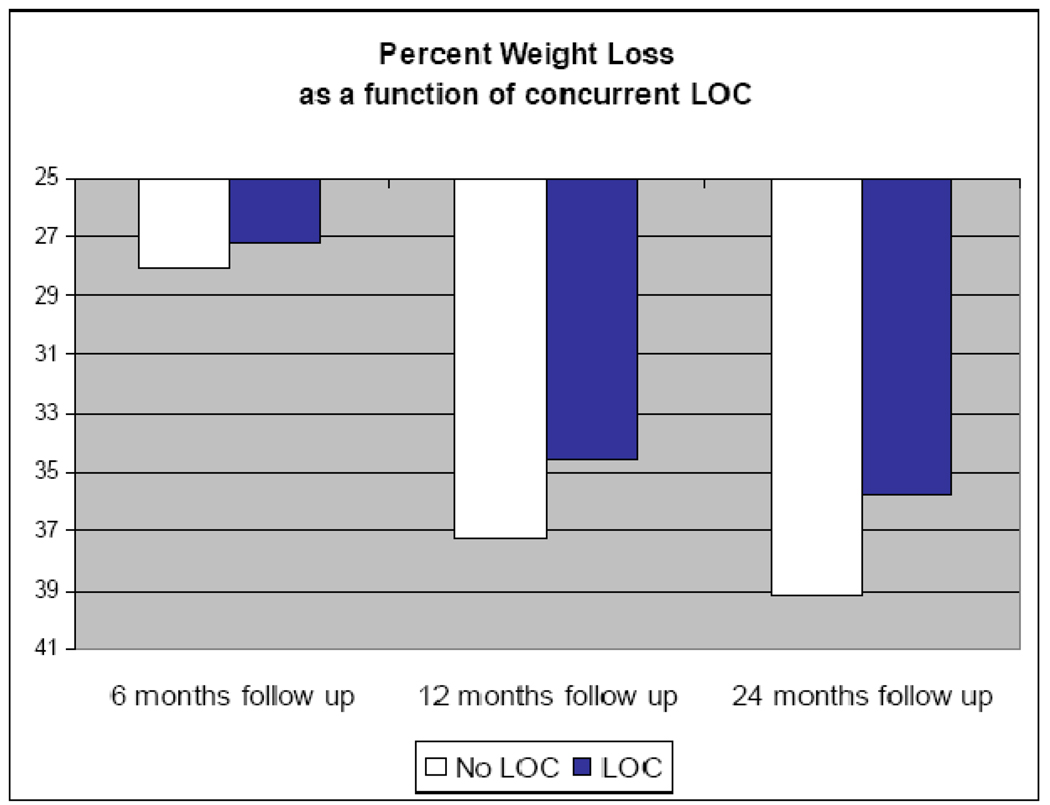

The hypothesis that weight loss (percent weight loss from pre-surgery weight) would be a function of pre-operative and post-operative LOC was tested with mixed model analysis. Variables entered into the initial analysis were baseline LOC, time-point-specific LOC (i.e., LOC status at each follow-up point), assessment time point, and all possible 2-way interactions. Non-significant interaction terms (at p>.10) were removed from analysis and tests of various covariance structures (i.e., unstructured, simple, toeplitz, compound symmetry, autoregressive) revealed that the autoregressive variance structure was most appropriate for the data. Results revealed that pre-operative LOC did not influence degree of weight loss, F(1,381)= 0.025, p=.87. Time point of assessment was a highly significant predictor of weight loss, F(1,338)=381.9, p<.001, as was post-operative LOC, F(1, 605) = 4.61, p=.032. None of the interaction terms was significant. Figure 2 demonstrates the pattern of percent weight loss as a function of post-operative LOC, measured at the concurrent assessment.

Figure 2.

Mean weight loss (% loss from baseline) as a function of point-specific LOC

To further investigate the pattern of weight loss over time as a function of LOC, analyses were repeated within time points (i.e., restricted to time-point specific outcomes). At the 6 month follow-up point, LOC did not predict weight loss (F(1,287) = 2.262, p=.134). LOC was a significant predictor of weight loss at 12 months (F(1, 272) = 7.595, p=.006), and at 24 months post-surgery (F(1,156) = 4.298, p=.040). At 12 months, the group reporting LOC lost a mean of 17.7 (sd=5.4) BMI units, whereas the group reporting no LOC had lost 19.1 (sd=5.4) BMI units; at 24 months, the mean BMI units lost were 18.3 (sd=6.0) and 20.5 (sd=6.9), respectively. Preoperative LOC did not significantly predict weight outcomes at any follow-up assessment point.

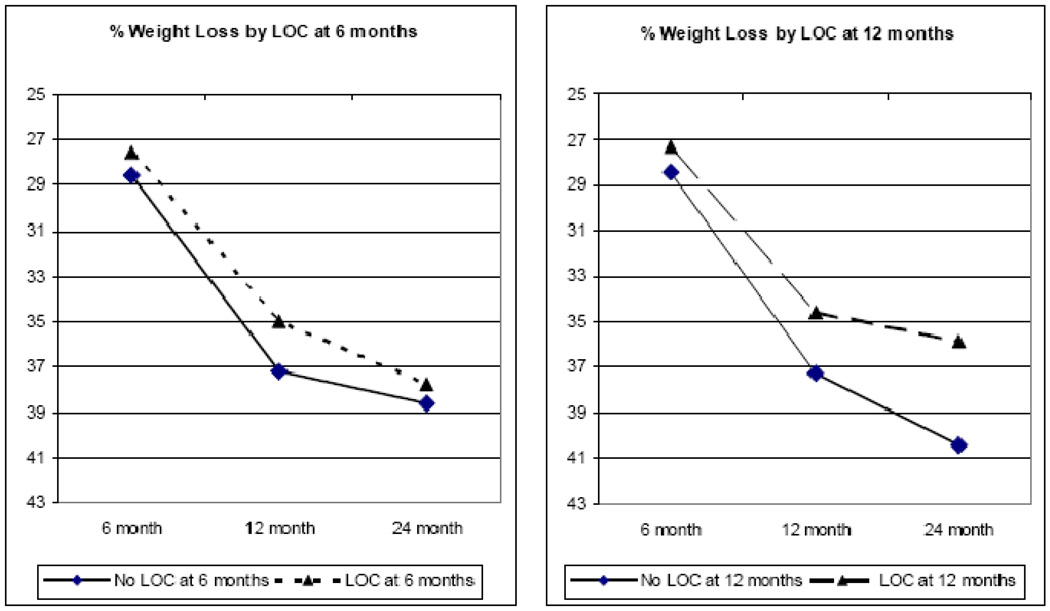

A series of analyses was conducted to test the prospective effects of LOC. Mixed models analysis revealed that LOC at 6 months significantly predicted weight loss at the latter follow-up points, F(1, 252) = 4.748, p=.03. Similarly, LOC at 12 months significantly predicted percent weight loss at 24 months, F(1, 130) = 8.788, p=.004. In terms of BMI units, the group reporting LOC at 12 months lost an average of 18.3 (sd=5.6) BMI units at the 24-month assessment, compared to an average 21.2 (sd=7.2) BMI unit loss for the group that had denied LOC at 12 months. The pattern of results in terms of percent weight loss is presented graphically in Figure 3. Finally, the influence of post-surgical LOC on weight regain from 12 to 24 months was examined. From 12 to 24 months, 32.6% (n=45) of the patients had regained ≥ 2 kg. Analysis by LOC category found that LOC at 12 months predicted weight regain; χ2= 3.855, p=.05, OR = 2.16 (95% CI: 0.995 – 4.687). Of those patients reporting LOC at 12 months, 44.2% went on to regain ≥ 2 kg between 12 and 24 months, whereas of those who did not report LOC, 26.8% went on to regain ≥ 2 kg.

Figure 3.

LOC prospective relations with percent weight loss

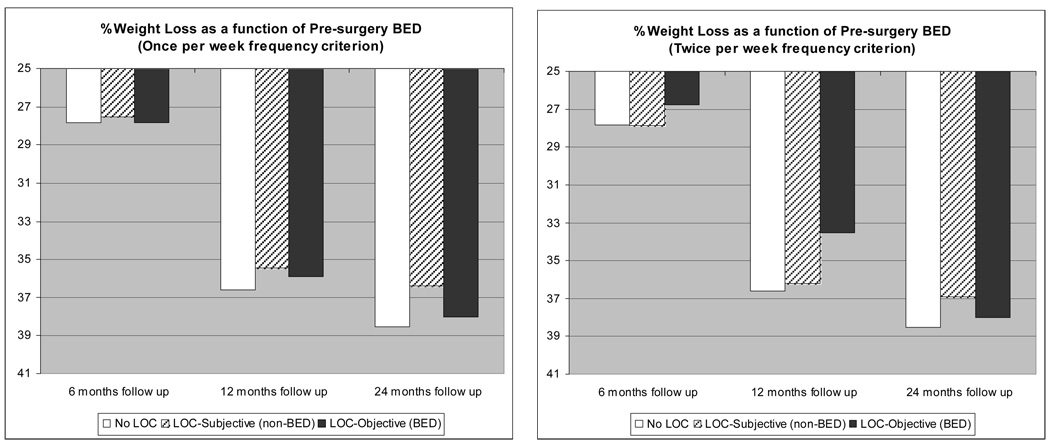

As a conservative test, the influence of pre-surgery binge eating (i.e., LOC over objectively large episodes of food) on post-operative weight loss was tested. Utilizing the DSM-IV-TR criterion for BED of binge eating twice weekly, patients were classified as either BED (i.e., loss of control over eating large amounts of food at least twice weekly), non-BED LOC (reporting loss of control but no overeating, or objective LOC but at sub-threshold frequency), and those denying LOC. Results showed no group differences at any of the follow-up points; the presence of BED prior to surgery did not affect weight outcomes. The analysis was repeated using a less stringent frequency criterion for binge eating episodes of once time per week. Again, the presence of binge eating at or approaching the diagnostic level for BED did not affect post-surgery weight outcomes. These results are depicted graphically in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Weight outcomes as a function of pre-surgery binge eating

Hypothesis 5

LOC would predict poorer psychosocial outcomes

Mixed models analyses were conducted to examine the influence of postoperative LOC on psychosocial outcomes. For each analysis, baseline scores on respective psychosocial outcomes were entered as covariates. Results paralleled the weight loss outcomes. For all analyses, time of assessment was highly significant, indicating substantial improvements in all measured psychosocial domains following surgery. Mixed models restricted to only post-surgical values also revealed significant time effects – indicating continued trajectories of improvement – for SF-36 mental and physical health, as well as for the EDEQ-Restraint, Eating Concerns, and Weight Concerns subscales. After controlling for baseline psychosocial variables, the effect of postoperative LOC on psychosocial outcomes was significant. The only exception was the SF-36 Physical Component score; postoperative LOC did not influence perceptions of postoperative physical functioning. As with weight loss outcomes, the pattern of differences between LOC groups was most prominent at 12 and 24 months outcomes; the uncorrected means at these time points are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Psychosocial outcomes at 12 and 24 months post-surgery as a function of concurrent LOC.

| 12 month follow-up | 24 month follow-up | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No LOC | LOC | Total | No LOC | LOC | Total | |||||||

| Psychosocial Outcome | ||||||||||||

| F-statistic of Mixed Model | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| BDI | ||||||||||||

| F(1, 751) = 8.80, p=.003 | 6.4 | (9.8) | 12.5 | (20.6) | 8.7 | (15.0) | 7.2 | (19.8) | 10.5 | (10.6) | 8.5 | (16.8) |

| SF36-MCS | ||||||||||||

| F(1, 696)=9.95, p=.002 | 53.2 | (10.5) | 48.0 | (12.8) | 51.3 | (11.7) | 52.3 | (10.6) | 45.9 | (14.3) | 49.8 | (12.5) |

| SF36-PCS | ||||||||||||

| F(1, 640)= 1.99, p=.159 | 50.6 | (9.2) | 47.6 | (10.8) | 49.5 | (9.9) | 49.2 | (10.7) | 46.5 | (11.6) | (11.6) | (11.1) |

| EDEQ Restraint | ||||||||||||

| F(1, 751) = 33.21, p<.001 | 1.8 | (1.4) | 2.3 | (1.4) | 2.0 | (1.5) | 1.4 | (1.3) | 2.4 | (1.4) | 1.8 | (1.4) |

| EDEQ Eating Concerns | ||||||||||||

| F(1, 734) = 104.5, p<.001 | 0.5 | (0.7) | 1.5 | (1.2) | 0.9 | (1.0) | 0.5 | (0.7) | 1.8 | (1.3) | 1.0 | (1.2) |

| EDEQ Shape Concerns | ||||||||||||

| F(1, 726) = 57.13, p<.001 | 2.0 | (1.3) | 2.8 | (1.3) | 2.3 | (1.4) | 2.1 | (1.4) | 3.3 | (1.3) | 2.6 | (1.5) |

| EDEQ Weight Concerns | ||||||||||||

| F(1, 743) = 59.99, p<.001 | 1.4 | (1.1) | 2.2 | (1.1) | 1.7 | (1.1) | 1.4 | (1.1) | 2.5 | (1.2) | 1.8 | (1.3) |

| EDEQ Total | ||||||||||||

| F(1, 718) = 88.42, p<.001 | 1.5 | (0.9) | 2.2 | (1.0) | 1.7 | (1.0) | 1.3 | (0.9) | 2.5 | (1.2) | 1.8 | (1.2) |

Note: F-statistics reflect results of Mixed Models Analysis; F-effect reported is for post-surgical LOC, after controlling for baseline values of specific psychosocial outcomes. Effects for time of assessment are not reported; all psychosocial domains improved following surgery.

Analyses to determine clinically significant Loss of Control

Finally, a series of analyses was conducted to determine a clinically significant cut-point for loss of control episodes. That is, we attempted to determine whether a severity or frequency threshold for LOC exists at which LOC must occur in order to affect outcomes. As reported above, the presence of LOC over unusually large eating episodes, and frequency at which they occurred prior to surgery, did not predict weight outcomes. The rates of LOC over unusually large episodes following surgery were too low to permit analysis with group contrasts (i.e., ANOVA designs), as were the rates of patients reporting LOC at least twice weekly. Therefore, patient groups were generated based on frequency of LOC episodes utilizing a once-per-week cut-point (i.e., once weekly vs. less than once weekly vs. none). Categorical analyses at each follow-up point revealed that frequency of LOC episodes was unrelated to weight loss at the concurrent time point.

As an additional test, LOC episodes were tallied and left as a continuous frequency variable. Table 4 summarizes correlation analyses testing whether the frequency of LOC episodes over the previous 28 days was related to psychosocial functioning following surgery. Moderate correlations were observed between LOC frequency and psychosocial and eating-specific impairment, and these correlations were stronger at the later time points (farther out from surgery). Overall, the most informative clinical cut point for predicting post-surgical weight outcomes appears to be the simple presence or absence of LOC following surgery. In terms of predicting post-surgical psychosocial outcomes, a graded effect exists, with increased frequency of LOC episodes generally associated with worsened clinical outcomes across both eating-specific and broad psychosocial outcomes.

Table 4.

Correlations: Frequency of LOC episodes with percent weight loss and psychosocial outcomes at each follow-up assessment

| Loss of Control Episodes (sum of Objective and Subjective) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | 12 months | 24 months | |

| Percent Weight Loss | −.10 | −.07 | −.03 |

| EDE-Q Restraint | .17 | .17 | .32* |

| EDE-Q Eating Concern | .40* | .49* | .63* |

| EDE-Q Shape Concern | .27* | .44* | .44* |

| EDE-Q Weight Concern | .24* | .40* | .52* |

| EDE-Q Total | .31* | .45* | .54* |

| BDI | .28* | .20 | .31* |

| SF36 - Physical | −.17 | −.17 | .06 |

| SF36 - Mental | −.18 | −.31* | −.42* |

Significant after correction for multiple (n=27) analyses (p<.001).

Discussion

This study investigated the prognostic significance of preoperative and postoperative loss of control over eating in extremely obese bariatric surgery patients over 24 months of prospective multi-wave follow-up. Prior to surgery, 61% of surgical patients reported LOC over eating, which is comparable to reports from other research groups utilizing similar assessment procedures (see 52 for a review). Preoperative LOC was associated concurrently with significantly elevated eating-disorder psychopathology and psychosocial difficulties and predicted prospectively postoperative LOC. Preoperative LOC, however, was unrelated to postoperative weight loss or psychosocial functioning. In contrast, LOC following surgery was a negative prognostic indicator for weight loss, with postoperative LOC predicting less weight loss at 12- and 24-month follow-up points. The influence of postoperative LOC became more pronounced as the time post-surgery increased, and may correspond with the weight-loss plateau that occurs some years following surgery 2, 53. Further, the rates of LOC increased over the course of the study: at 6 month follow-up, approximately 31% of the sample reported LOC, and by the 24 month follow-up this percentage had increased to 39% overall, and to nearly 50% among those experiencing LOC prior to surgery. The group reporting postoperative LOC reported elevated depressive symptoms and eating disturbances, as well as lower levels of quality of life as measured by the Mental Components summary scale of the SF-36. Of note, LOC was not predictive of the Physical Component summary scale, suggesting that the significant physical improvements attained through bariatric surgery are not easily influenced by a subjective sense of loss of control. On the other hand, LOC does predict important bariatric outcomes such as eating-specific and broad psychosocial functioning in addition to weight loss.

The current findings add to the emerging literature showing considerable improvements following bariatric surgery, both in terms of weight loss and psychosocial outcomes through 24-months post-surgery. A substantial percentage of patients, however, begins to plateau by 12 to 24 months post-surgery and may experience weight regain 54. In the current study, through 24-months of post-surgical follow-up, LOC following surgery was significantly associated with weight regain at subsequent assessment points. Collectively, research investigating pre-surgical psychosocial, historical, and even eating-specific factors has reported little impact on post-surgical outcomes 3, 5, 55. This is a limitation, since identification of such characteristics would suggest the need for supplemental treatments to ensure maximum treatment benefit. Therefore our inclusion of both pre-surgical and post-surgical problematic eating marks one of the first studies to prospectively identify patient-specific factors predicting a worsened clinical profile, and identifies a potential area for clinical intervention.

Our results support and extend findings from previous research reporting that preoperative binge eating and/or loss of control over eating does not impede weight loss 11, 17, 21–24 . Collectively this research indicates that preoperative binge eating, although common 52, may not require specific additional clinical intervention before treatment. Our results, however, do suggest that the emergence of post-operative eating problems has negative prognostic influence on weight loss outcomes, as well as some of the psychosocial benefits associated with surgery. The current study parallels previous research with other patient groups 29–31 identifying the clinical significance of LOC over eating as a correlate of eating-specific and more global psychopathology. Therefore post-surgical LOC over eating, although subclinical in nature, should be the target of clinical intervention following surgery. Given that nearly 40% of the patients in this study reported LOC over eating in the 24 months following surgery, these findings also suggest that a substantial proportion of bariatric surgery patients may benefit from continued clinical care. Specifically, the subjective sense of a loss of control over eating has significant impact on weight and psychosocial outcomes, independent of the amount of food that is consumed. Clinicians working with this patient group should be aware that various aspects of eating disturbance are more clinically relevant than the mere amount of food consumed. In terms of identifying patients at risk for psychosocial difficulties or distress, LOC is a good proxy or marker for identifying those patients who may benefit from more clinical attention to manage their distress. Clinicians can readily assess whether a patient experiences subjective LOC over eating episodes based on verbal report. Further, clinicians should be aware that while the mere presence or absence of LOC following surgery predicts weight outcomes, a graded effect exists such that the frequency of LOC predicts worsened psychosocial outcomes. An apt focus of clinical attention would be on developing coping strategies or on cognitive restructuring adapted from the best-established treatments for eating disorders 56. Future research will be required to identify the best treatments to ensure weight maintenance or continued losses in the years following surgery.

This study has some potential limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. The findings pertain to extremely obese patients who seek bariatric surgery at an urban general medical center and undergo gastric bypass procedures. The findings may not generalize to less obese patients or to obese patients who seek different (non-surgical) forms of treatment or different forms of bariatric surgeries. Although the questionnaire we used to assess LOC elicits specific estimates in terms of the number of eating episodes in which LOC was experienced, self-report measures are potentially limited by retrospective recall and response biases. Previous psychometric evaluations have found that the EDE-Q may overestimate certain aspects of eating pathology relative to clinician interview 42, 57, so it is possible that the rates of LOC were over-reported. Alternatively, some research suggests that patients are more candid when reporting symptoms in questionnaire format than in clinician interview 58. Our reliance on self-reported weights is an additional limitation, however research has found that self-reported weight is an adequate proxy for measured weights 59, 60. Since we were primarily interested in time-varying outcomes, however, we opted to employ self-reported data corresponding with the time of assessment rather than measured weights taken at a different time-point. The findings are further limited by the amount of missing data, particularly for the 24-month follow-up point, although the use of mixed models analyses permitted use of all available data for all participants, and these models offer important advantages over other methods of imputation for missing data in longitudinal research 61. However, it should be noted that our analyses on the rate of dropout found few differences between participants who provided data at the follow-up points compared to those who did not; participants providing follow-up data at 24 months did not differ from those who did not on any outcome variable measured at 12 months.

Another potential limitation is the possibility that extremely obese patients seeking bariatric surgery may minimize the existence of certain problems (e.g., distress level, binge eating) in order to appear psychologically healthy and appropriate for the surgery. Indeed, research has shown that patients undergoing psychological evaluation prior to surgery have elevated scores on social desirability and commonly deny active problems 62. Although this possibility must be considered, the research study procedures and informed consent methods should have served to minimize this likelihood. Specifically, participants completed the assessments as part of a research study and were informed that the results would not be shared with the clinical treatment team unless the patients specifically requested it. It was stressed that the assessments would have no medical benefit to patients, and were intended solely to advance knowledge regarding psychosocial needs and outcomes of bariatric surgery patients. Further, LOC predicted emotional and psychological outcomes, but not physical domains, which suggests that response sets were not responsible for the pattern of results. Finally, since baseline prevalence of LOC was much higher than prevalence of LOC post-surgery, the possibility that patients minimized problems prior to surgery is unlikely.

In summary, this study examined pre-operative and post-operative loss of control over eating in relation to 6-, 12-, and 24-month postoperative outcomes in gastric bypass patients. The findings suggest that preoperative LOC does not appear to be a negative prognostic indicator for gastric bypass surgery. However, postoperative LOC does appear to impede the rate of weight loss, particularly as the time-since-surgery increases. Similarly, postoperative LOC predicts psychosocial outcomes, including depressive symptoms, additional eating disturbances, and some aspects of quality of life. Therefore postoperative LOC over eating is a useful indicator of attenuated post-surgical improvements and may warrant clinical focus in post-surgical care. Longer-term follow-up is needed to determine the durability of these outcomes.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Ross D. Crosby, PhD, for his statistical guidance.

Disclosures: This research and the authors were supported by grants K23 DK062291 (Dr. Kalarchian), K23 DK071646 (Dr. White), and K24 DK070052 (Dr. Grilo) from the National Institutes of Health and by the Donaghue Medical Research Foundation (Dr. Grilo).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors report no competing interests, financial or otherwise, for this work.

A preliminary version of the current research was presented at the Annual Conference of the Eating Disorders Research Society, October 2007, Pittsburgh, PA.

Participants who completed the follow-up assessments did not differ from those who did not in terms of preoperative BMI, LOC, or psychological functioning (BDI, SF-36, or EDE-Q scores) with one exception. Participants who did not complete the 24-month assessment had reported significantly higher levels of dietary restraint prior to surgery than those who completed the follow-up; the groups did not differ on restraint measured at 6 months or 12 months. The group that participated in the 24 month assessment did not differ from the group that did not on weight loss, LOC, BDI, SF-36, or EDE-Q scores measured at 12 months.

References

- 1.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. 2004;292(14):1724–1737. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(26):2683–2693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarwer DB, Wadden TA, Fabricatore AN. Psychosocial and behavioral aspects of bariatric surgery. Obes Res. 2005;13(4):639–648. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Hout GC, Boekestein P, Fortuin FA, Pelle AJ, van Heck GL. Psychosocial functioning following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2006;16(6):787–794. doi: 10.1381/096089206777346808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herpertz S, Kielmann R, Wolf AM, Hebebrand J, Senf W. Do psychosocial variables predict weight loss or mental health after obesity surgery? A systematic review. Obes Res. 2004;12(10):1554–1569. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masheb RM, White MA, Toth CM, Burke-Martindale CH, Rothschild B, Grilo CM. The prognostic significance of depressive symptoms for predicting quality of life 12 months after gastric bypass. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48(3):231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grilo CM, White MA, Masheb RM, Rothschild BS, Burke-Martindale CH. Relation of childhood sexual abuse and other forms of maltreatment to 12-month postoperative outcomes in extremely obese gastric bypass patients. Obes Surg. 2006;16(4):454–460. doi: 10.1381/096089206776327288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rusch MD, Andris D. Maladaptive eating patterns after weight-loss surgery. Nutr Clin Pract. 2007;22(1):41–49. doi: 10.1177/011542650702200141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalarchian MA, Wilson GT, Brolin RE, Bradley L. Binge eating in bariatric surgery patients. Int J Eat Disord. 1998;23(1):89–92. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199801)23:1<89::aid-eat11>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elder KA, Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Rothschild BS, Burke-Martindale CH, Brody ML. Comparison of two self-report instruments for assessing binge eating in bariatric surgery candidates. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44:545–560. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White MA, Masheb RM, Rothschild BS, Burke-Martindale CH, Grilo CM. The prognostic significance of regular binge eating in extremely obese gastric bypass patients: 12-month postoperative outcomes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(12):1928–1935. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Levine MD, et al. Psychiatric disorders among bariatric surgery candidates: relationship to obesity and functional health status. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):328–334. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.328. quiz 74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenberger PH, Henderson KE, Grilo CM. Psychiatric disorder comorbidity and association with eating disorders in bariatric surgery patients: a cross-sectional study using structured interview-based diagnosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1080–1085. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual - Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Zwaan M, Mitchell JE, Howell LM, et al. Characteristics of morbidly obese patients before gastric bypass surgery. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2003;44(5):428–434. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazzeo SE, Saunders R, Mitchell KS. Binge eating among African American and Caucasian bariatric surgery candidates. Eat Behav. 2005;6(3):189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powers PS, Perez A, Boyd F, Rosemurgy A. Eating pathology before and after bariatric surgery: a prospective study. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;25(3):293–300. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199904)25:3<293::aid-eat7>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wadden TA, Sarwer DB, Womble LG, Foster GD, McGuckin BG, Schimmel A. Psychosocial aspects of obesity and obesity surgery. Surg Clin North Am. 2001;81(5):1001–1024. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70181-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Zwaan M, Lancaster KL, Mitchell JE, et al. Health-related quality of life in morbidly obese patients: effect of gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 2002;12(6):773–780. doi: 10.1381/096089202320995547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pekkarinen T, Koskela K, Huikuri K, Mustajoki P. Long-term Results of Gastroplasty for Morbid Obesity: Binge-Eating as a Predictor of Poor Outcome. Obes Surg. 1994;4(3):248–255. doi: 10.1381/096089294765558467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Latner JD, Wetzler S, Goodman ER, Glinski J. Gastric bypass in a low-income, inner-city population: eating disturbances and weight loss. Obes Res. 2004;12(6):956–961. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burgmer R, Grigutsch K, Zipfel S, et al. The influence of eating behavior and eating pathology on weight loss after gastric restriction operations. Obes Surg. 2005;15(5):684–691. doi: 10.1381/0960892053923798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malone M, Alger-Mayer S. Binge status and quality of life after gastric bypass surgery: a one-year study. Obes Res. 2004;12(3):473–481. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green AE, Dymek-Valentine M, Pytluk S, Le Grange D, Alverdy J. Psychosocial outcome of gastric bypass surgery for patients with and without binge eating. Obes Surg. 2004;14(7):975–985. doi: 10.1381/0960892041719590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kalarchian MA, Wilson GT, Brolin RE, Bradley L. Effects of bariatric surgery on binge eating and related psychopathology. Eat Weight Disord. 1999;4(1):1–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03376581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsu LK, Sullivan SP, Benotti PN. Eating disturbances and outcome of gastric bypass surgery: a pilot study. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;21(4):385–390. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(1997)21:4<385::aid-eat12>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guss JL, Kissileff HR, Devlin MJ, Zimmerli E, Walsh BT. Binge size increases with body mass index in women with binge-eating disorder. Obes Res. 2002;10(10):1021–1029. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Theim KR, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Salaita CG, et al. Children's descriptions of the foods consumed during loss of control eating episodes. Eat Behav. 2007;8(2):258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Latner JD, Hildebrandt T, Rosewall JK, Chisholm AM, Hayashi K. Loss of control over eating reflects eating disturbances and general psychopathology. Behav Res Ther. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elder K, Paris M, Anez L, Grilo C. Loss of control over eating is associated with eating disorder psychopathology. Eat Behav. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2008.04.003. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colles SL, Dixon JB, O'Brien PE. Loss of control is central to psychological disturbance associated with binge eating disorder. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(3):608–614. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Wilson GT, Labouvie EW, Brolin RE, LaMarca LB. Binge eating among gastric bypass patients at long-term follow-up. Obes Surg. 2002;12(2):270–275. doi: 10.1381/096089202762552494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colles SL, Dixon JB, O'Brien PE. Grazing and Loss of Control Related to Eating: Two High-risk Factors Following Bariatric Surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(3):615–622. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16(4):363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: nature, assessment, and treatment. 12th ed. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reas DL, Grilo CM, Masheb RM. Reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire in patients with binge eating disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(1):43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Black CM, Wilson GT. Assessment of eating disorders: interview versus questionnaire. Int J Eat Disord. 1996;20(1):43–50. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199607)20:1<43::AID-EAT5>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. A comparison of different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(2):317–322. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder: a replication. Obes Res. 2001;9(7):418–422. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont PJ. Validity of the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) in screening for eating disorders in community samples. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42(5):551–567. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00161-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilfley DE, Schwartz MB, Spurrell EB, Fairburn CG. Assessing the specific psychopathology of binge eating disorder patients: interview or self-report? Behav Res Ther. 1997;35(12):1151–1159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kalarchian MA, Wilson GT, Brolin RE, Bradley L. Assessment of eating disorders in bariatric surgery candidates: self-report questionnaire versus interview. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28(4):465–469. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200012)28:4<465::aid-eat17>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beck AT, Steer R. Manual for Revised Beck Depression Inventory. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beck AT, Steer R, Garbin MG. Psychometric Properties of the Beck Depression Inventory - 25 Years of Evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8(1):77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watson D, Clark LA. Negative affectivity: the disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychol Bull. 1984;96(3):465–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Subtyping binge eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(6):1066–1072. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.6.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Canoy D, Wareham N, Luben R, et al. Cigarette smoking and fat distribution in 21,828 British men and women: a population-based study. Obes Res. 2005;13(8):1466–1475. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Lu JF, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32(1):40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31(3):247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ware JE, Jr, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales -- A User's Manual. Boston: New England Medical Center, The Health Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Niego SH, Kofman MD, Weiss JJ, Geliebter A. Binge eating in the bariatric surgery population: a review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(4):349–359. doi: 10.1002/eat.20376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pories WJ, MacDonald KG, Jr, Morgan EJ, et al. Surgical treatment of obesity and its effect on diabetes: 10-y follow-up. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;55(2 Suppl):582S–585S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/55.2.582s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Magro DO, Geloneze B, Delfini R, Pareja BC, Callejas F, Pareja JC. Long-term Weight Regain after Gastric Bypass: A 5-year Prospective Study. Obes Surg. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9265-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Hout GC, Verschure SK, van Heck GL. Psychosocial predictors of success following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2005;15(4):552–560. doi: 10.1381/0960892053723484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilson GT, Grilo CM, Vitousek KM. Psychological treatment of eating disorders. Am Psychol. 2007;62(3):199–216. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Zwaan M, Mitchell JE, Swan-Kermeier L, et al. A comparison of different methods of assessing the features of eating disorders in post-gastric bypass patients: a pilot study. Eur Eat Disorders Rev. 2004;12:380–386. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Keel PK, Crow S, Davis TL, Mitchell JE. Assessment of eating disorders: comparison of interview and questionnaire data from a long-term follow-up study of bulimia nervosa. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(5):1043–1047. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00491-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kuczmarski MF, Kuczmarski RJ, Najjar M. Effects of age on validity of self-reported height, weight, and body mass index: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101(1):28–34. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00008-6. quiz 5–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stunkard AJ, Albaum JM. The accuracy of self-reported weights. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34(8):1593–1599. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/34.8.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gueorguieva R, Krystal JH. Move over ANOVA: progress in analyzing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the Archives of General Psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(3):310–317. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Glinski J, Wetzler S, Goodman E. The psychology of gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 2001;11(5):581–588. doi: 10.1381/09608920160557057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]