Abstract

Thyroid hormone influences diverse metabolic pathways important in lipid and glucose metabolism, lipolysis, and regulation of body weight. Recently, it has been recognized that thyroid hormone receptor (TR) interacts with transcription factors that predominantly respond to nutrient signals including the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs), liver X receptor (LXR), and others. Crosstalk between thyroid hormone signaling and these nutrient responsive factors occurs through a variety of mechanisms: competition for retinoid X receptor (RXR) heterodimer partners, DNA binding sites, and transcriptional co-factors. This review focuses on the mechanisms of interaction of thyroid hormone signaling with other metabolic pathways, and the importance of understanding these interactions to develop therapeutic agents for treatment of metabolic disorders, such as dyslipidemias, obesity, and diabetes.

Thyroid Hormone and Metabolism

Thyroid hormone is a key metabolic regulator coordinating short-term and long-term energy needs [1]. Significant metabolic changes are seen with variations in thyroid status in humans [2]. Hyperthyroidism, characterized by elevated serum thyroid hormone levels, is associated with accelerated metabolism, increased lipolysis, weight loss, increased hepatic cholesterol biosynthesis and excretion, and reduced serum cholesterol levels. Hypothyroidism, characterized by low serum thyroid hormone levels, is associated with reduced metabolism, reduced lipolysis, weight gain, reduced cholesterol clearance, and elevated serum cholesterol. With low food intake, nutrient and other feedback is integrated centrally to reduce thyroid hormone production, resulting in lower metabolic rate and shifting the body to an energy conservation mode [3]. In fact, body weight in humans is inversely correlated with thyroid hormone levels [4]. Many of the actions of thyroid hormone in metabolic regulation involve modulation of other metabolic signaling pathways (Table 1).

Table 1.

Metabolic Processes Modulated by Thyroid Hormone Signaling

| Process | Factors That Stimulate or Modulated |

T3 Ligand Effects | Thyroid Hormone Target(s) (*downregulates expression) |

Interacting Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal Metabolic Rate | T3, Metabolic Processes |

Stimulates | Na+/K+ ATPase, SERCA-1, UCPs, LPL |

Adrenergic |

| Adaptive Thermogenesis |

Cold Exposure, Food Ingestion |

Stimulates | UCP1, PEPCK | Adrenergic, Bile Acids, Gluconeogenesis |

| Regulation of Body Weight |

Nutrient Intake |

Integrates balance with nutrient intake signals |

TRH*, TSH*, spot 14 (Thrsp), D2* |

TRH, Leptin, Adrenergic, CART, neuropeptide Y, D2 |

| Cholesterol Synthesis and Efflux |

Cholesterol Levels |

Promotes cholesterol synthesis, efflux |

LDL-R, ABCA1 | Sterol signaling (SREBP), PPARα, LXR |

| Fatty Acid Synthesis and Oxidation |

Fat Intake, Fat Storage, Long- Chain Fatty Acids |

Promotes lipolysis and β-oxidation |

CPT1α | Adrenergic, PPARα, LXR |

| Bile Acid Synthesis | Fat Intake | Decrease (humans) | CYP7A1*(human) | TGR5, D2, FXR, PPARα |

| Glucose Metabolism | Carbohydrate intake, Serum glucose/insulin |

Stimulates gluconeogenesis, Impairs insulin secretion |

ACC1, GLUT4, ChREBP |

Glucose, Insulin, PPARα, LXR, SREBP, RXR |

ACC1-acetyl-CoA carboxylase, ACO-Acyl-CoA oxidase, CART-cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcripts, CETP-cholesteryl ester transfer protein, ChREBP-carbohydrate response element binding protein, CPT1α- carnityl palmotoyl transferase Iα CYP7A1-cholesterol 7-hydroxylase, D2-5′-deiodinase Type 2, FXR-farnesoid X receptor, LPL-lipoprotein lipase, LXR-liver X receptor, PPARα -peroxisome proliferator activated receptor, PEPCK-phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, RXR-retinoid X receptor, SERCA-sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium, T3-triiodothyronine, TGR5- G protein coupled receptor bile acid receptor, TRH-thyrotropin releasing hormone, TSH-thyroid stimulating hormone, UCP-uncoupling protein

Thyroid Hormone Action

Thyroid hormone acts predominantly through its nuclear receptors, thyroid hormone receptor (TR) α and β, which are differentially expressed developmentally and in adult tissues [1]. TR isoform-specific metabolic functions have been identified, and selective TR agonists have been developed to stimulate specific metabolic pathways [5,6]. The functional TR complex consists of a heterodimer with retinoid X receptor (RXR) that binds to a thyroid hormone response element (TRE) to modulate gene expression. Liganded TR stimulates genes positively regulated by triiodothyronine (T3), while unliganded TR binds to a TRE to repress those genes. The repressive actions of unliganded TR are important in metabolic regulation, especially in antagonizing the action of other nuclear receptors [7].

The prohormone thyroxine (T4) is converted to the active hormone T3, by the Type 1 (D1) and Type 2 (D2) 5′-deiodinases. D1, expressed on the cell membrane, is stimulated by T3 at the transcriptional level and contributes to circulating T3 [8]. D2 is expressed in the cytoplasm, rapidly produces T3 at the local tissue level, and is regulated through ubiquitination/deubiquitination [8]. Active deubiquinated D2 is the result of adrenergic stimulation, reduced T4 substrate and bile acids [8,9]. D2 is expressed in the hypothalamus and pituitary, and is important in producing the T3 that mediates thyroid hormone feedback through down-regulation of thyrotropin (TSH) and thyrotropin releasing hormone (TRH) [3]. Ligand activation by the 5′-deiodinases, therefore, is important in metabolic regulation influencing thyroid hormone production, circulating T3, and T3 levels in tissues.

Metabolic Processes Regulated by Thyroid Hormone

Thyroid hormone regulates basal metabolic rate through known targets such as Na/K ATPase, although the overall mechanism is not well established [10]. Thyroid hormone interacts closely with the adrenergic nervous system to generate heat in response to cold exposure, termed adaptive thermogenesis, best characterized mechanistically in rodent brown adipose tissue (BAT) [11]. This process stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis and upregulation of fatty acid oxidation. The conversion of T4 to T3 by D2, along with expression of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1), is required for adaptive thermogenesis and is stimulated by catecholamines [11]. Gluconeogenesis is also stimulated by catecholamines and thyroid hormone [12]. The UCP1 promoter and the promoter for a rate-limiting enzyme in gluconeogenesis, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), have a cAMP response element (CRE) and TRE in close proximity, and both response elements are required to stimulate gene expression [11]. Mice with inactivation of the D2 gene, important for generating T3 in tissues such as brain and BAT, have impaired adaptive thermogenesis [8]. The mechanisms for thyroid hormone interactions with the adrenergic system involves coordinate regulation of ligand availability, direct gene regulation by TR, as well as co-regulation of some genes by TR and adrenergic-stimulated factors.

The TRα and TRβ isoforms have specific roles in thyroid hormone-adrenergic interactions in white adipose tissue (WAT) and BAT [13-15]. Both TRα and TRβ are required for BAT adaptive thermogenesis [13-15]. The TRα isoform is required for thyroid hormone potentiation of the lipolytic actions of catecholamines in WAT [13] and BAT [14]. The TR isoform is required for stimulation of UCP1 expression in BAT [15]. These TR isoform-specific roles have been demonstrated using selective pharmacologic agonists as well as mouse models with TR deletions and mutations, indicating that these actions are directly related to properties of the specific TR isoform.

The thyroid gland is regulated by TSH secreted from the pituitary, under the control of TRH from the hypothalamus [3,16]. Neurons in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) produce TRH, and both TRH and TSH are negatively regulated by T4 and T3. TRH is expressed throughout the brain and spinal cord, but only TRH in the PVN is regulated by thyroid hormone. The adrenergic nervous system, leptin, cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript (CART), α-Melanocyte Stimulating Hormone, and Neuropeptide Y (NPY), regulate nutrient intake, appetite, thermogenesis, and body weight [3,16]. There is evidence for anatomical connection of neurons in these pathways with the hypophysiotropic TRH neuron, as well as regulatory sites in the TRH gene that bind factors that mediate these effects [16]. Catecholamines raise the set-point for TRH inhibition by T3, promoting higher thyroid hormone levels and greater thermogenesis. CART stimulates TRH synthesis and release, and NPY inhibits TRH transcription. When fat stores are low and leptin levels reduced, there is a lowering of the TRH set-point and subsequently, lower TRH, TSH, and circulating thyroid hormone levels. Signals that reflect nutrient balance, therefore, can increase or decrease TRH feedback sensitivity and raise or lower thyroid hormone levels.

Glucose metabolism is influenced by thyroid hormone status [12]. Specifically, excess thyroid hormone stimulates hepatic glucose production, increases the expression of the glucose transporter GLUT4 in skeletal muscle, and reduces insulin levels, in part through accelerated insulin degradation [17]. Liganded TR impairs glucose-stimulated insulin secretion acting directly at the level of the islet, but this effect is rescued by liganded PPARα [18,19]. A further link between glucose metabolism and thyroid hormone signaling is T3-stimulation of the carbohydrate response element binding protein (ChREBP), a basic/helix-loop-helix/leucine zipper transcription factor that stimulates expression of enzymes promoting glycolysis and lipogenesis in response to glucose and insulin [20]. Thyroid hormone influences glucose metabolism by direct actions reducing insulin levels, regulating expression of genes in the liver and skeletal muscle, and stimulating expression of additional factors, such as ChREBP, that then influence glucose response and insulin secretion.

Thyroid hormone stimulates both lipolysis and lipogenesis. T3 treatment in rats stimulates thermogenesis from fatty acid β-oxidation as a result of lipolysis and increased caloric intake [21]. Lipogenesis is also stimulated by T3, but to a lesser degree than lipolysis and primarily to restore depleted fat stores [21]. Cholesterol reduction is predominantly mediated by T3-stimulation of expression of the low density lipoprotein receptor (LDL-R) as well as T3-stimulation of sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBPs) that also stimulates LDL-R [5,6]. Mouse models with TRα and TRβ gene point mutations show a range of metabolic phenotypes including impairment of cholesterol metabolism, fatty acid oxidation, lipolysis, and increased cholesterol and triglyceride serum levels [22,23]. Studies of rodents and primates treated with TR β-selective agonists show a reduction in serum cholesterol, lipoprotein a (Lpa), triglycerides, and body weight [6,24]. These studies all indicate the importance of thyroid hormone signaling as a therapeutic target in metabolic dysfunction.

The remainder of the review focuses on the interaction of thyroid hormone signaling with nuclear receptors and transcription factors involved with lipid and glucose regulation including the mechanism, physiological relevance, and implications of these interactions for selective therapeutic targets.

Receptor Structure and Response Element Features Promoting Interaction

TR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) α and γ, and Liver X Receptor (LXR) are ligand-activated nuclear receptors that share a similar structure and mode of action, and all heterodimerize with RXR [1,25]. They have a highly conserved DNA binding domain, which contains two zinc fingers that recognize DNA response elements. These elements in the regulatory region of gene targets consist of hexameric half-sites arranged as direct repeats with variable spacing. TR, PPAR and LXR recognize the same hexameric “half-site” sequence AGGTCA. TR and LXR recognize an identical consensus response element that is a direct repeat with a 4 base pair gap (DR4) (AGGTCAnnnnAGGTCA). The ligand binding domain (LBD) identifies specific ligands for each receptor and contains regions that interface with other receptors as well as coactivators and corepressors. TR binds to thyroid hormone with high affinity (Ka ~0.5 nM), while PPAR and LXR bind to their natural nutrient ligands with low affinity (Ka in μM range)[25]. TR and PPAR share identical ninth heptad repeats in their LBDs, which are structurally similar to the leucine zipper in LXR. The leucine zipper, which is the interface for heterodimerization with RXR, is highly conserved among nuclear receptors. The structural similarity among TR and the nutrient receptors PPAR and LXR in the DNA binding and ligand domains indicate the potential for direct interactions at these sites

Heterodimer partners of RXR can be categorized as “permissive” or “nonpermissive” [25]. “Permissive” RXR partners bind dietary lipids with low affinity and activate enzymes that regulate lipid metabolism in “feed-forward” regulation, and examples include PPAR and LXR. “Non-permissive” RXR heterodimers are high affinity hormone receptors such as TR that mediate feedback regulation of their ligand. Thyroid hormone, with higher affinity for TR and “dominance” in its interaction with RXR, might have a greater effect in co-regulated genes than nutrient signals acting through PPAR and LXR. Furthermore, long-chain fatty acids, at least in vitro, can inhibit T3 binding to TR, suggesting another potential path of regulation at the level of nutrient signaling and T3 binding to TR [26].

A heterodimer complex of TR, PPAR or LXR with RXR is required to recruit coactivators and act as a transcription regulator [1,25]. For example, RXR is a limiting factor for the hormone response in some tissues, and competition for RXR among nuclear receptors influences gene expression [25,27]. PPAR and interfere with TR signaling by binding RXR and possibly other limiting TR co-factors [27].

Thyroid hormone regulates expression of the SREBPs, key regulators of lipid metabolism. The mature SREBPs are basic-helix-loop-helix-leuzine zipper (bHLH-LZ) transcription factors. The BHLH-LZ domain is responsible for both DNA binding and dimerization. The SREBP-1c isoform is involved in fatty acid synthesis and glucose metabolism, and the SREBP-2 isoform is a lipid sensor important in cholesterol metabolism. Thyroid hormone induces SREBP-2 gene expression [28] and represses SREBP-1c gene expression [29]. SREBPs form homodimers that recognize a nonpalindromic sterol response element (SRE) and dimerize on inverted repeats [30]. Several genes have a tandem arrangement of the TRE and SRE, which positions TR and SREBP in close proximity. For example, both the TRE and SRE are required for activation of human acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) 1 [31] and low density lipoprotein receptor (LDL-R) genes [32]. Thyroid hormone directly regulates SREBPs, but also co-regulates genes with the TREs and SREs located in close proximity in co-regulated genes.

Cholesterol Regulation

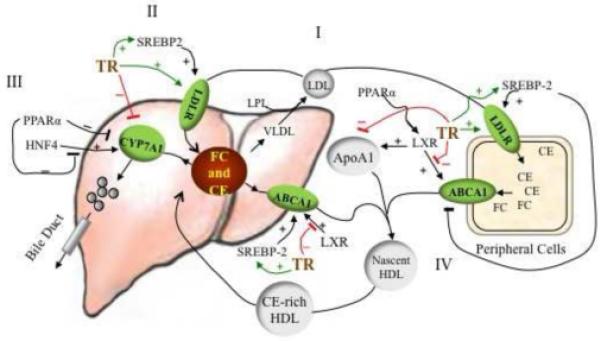

Thyroid hormone reduces serum levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) primarily by stimulating LDL-R [32] (Figure 1). Two TREs have been identified in the rat LDL-R gene promoter that mediate T3 induction [32]. In fact, patients with overt hypothyroidism have hypercholesterolemia and LDL accumulation in the liver, which can be normalized with thyroxine treatment [2].

Figure 1.

Crosstalk between Thyroid Hormone Signaling and Pathways in Cholesterol Metabolism. (i) Cholesterol in the form of low density lipoprotein (LDL) is transported from the liver to peripheral tissues by LDL receptor (LDL-R). (ii) Thyroid hormone receptor (TR) and sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP)-2 stimulate LDL-R gene expression and increase cholesterol uptake. SREBP-2 gene expression is stimulated by thyroid hormone signaling and feedback-regulation by sterols. (iii) The excess cholesterol in liver is converted to bile acids, catalyzed by cholesterol 7-hydroxylase (CYP7A1). This bile acid feedback is modulated by multiple nuclear receptors regulating CYP7A1 gene expression. Liganded TR and peroxisome proliferator activated (PPAR)α inhibit, and hepatic nuclear factor (HNF)4α stimulates, CYP7A1 gene expression and bile acid synthesis (thyroid hormone stimulates CYP7A1 expression in mice, see description in text). (iv) Cholesterol efflux in peripheral tissue relies on the ATP-binding-cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) transporter. Cholesterol is transported by ABCA1 to lipid-poor apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1) to form nascent high density lipoprotein (HDL). Cholesteryl ester-rich HDL enters the circulation and transports cholesterol back to liver through SRB1 or LDL-R or cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) for disposal. Liver X receptor (LXR) stimulates ABCA1 activity. T3 inhibits LXR-stimulated ABCA1 gene expression by competing for DNA binding sites and for the heterodimer partner retinoid X receptor (RXR). PPARα agonists stimulate cholesterol efflux by increasing expression of LXR. CE-cholesteryl ester, FC-free cholesterol

In addition to stimulation by T3, the LDL-R gene is subject to feedback regulation by SREBP-2 [33]. In the presence of high sterol levels, the LDL-R promoter is inactive. When low levels of cholesterol are sensed, SREBP-2 is transported by SREBP cleavage-activating protein (SCAP) to the Golgi apparatus where it is sequentially cleaved by two enzymes (SP1 and SP2) to generate mature SREBP-2 [33]. SREBP-2 is transferred to the nucleus and binds to the SRE in the LDL-R gene promoter. This activates LDL-R gene expression and facilitates the uptake of cholesterol and enhances cholesterol synthesis. T3 and sterol levels, therefore, regulate LDL-R expression.

SREBP-2 gene expression, however, in addition to feedback regulation by sterols is also directly regulated by thyroid hormone. In hypothyroid rats, Srebp-2 mRNA expression is not detectable, but is restored after T3 treatment [28]. Several functional TREs have been identified in the mouse Srebp-2 promoter. T3 stimulation of Srebp-2 mRNA activates SREBP-2 gene targets, such as LDL-R and HMG (3-hydro-3-methylglutaryl)-CoA Reductase. On the other hand, PPARα reduces SREBP-2 protein maturation leading to reduced functional SREBP-2, reduced HMG -CoA reductase expression and reduced cholesterol synthesis [34]. Thyroid hormone and sterol signaling regulate SREBP-2 expression

Cholesterol Efflux

Cholesterol efflux involves reverse cholesterol transport of excess cholesterol from peripheral tissue through vessel walls to the liver, and conversion of excess cholesterol through synthesis and excretion of bile acid in the liver (Figure 1). Most cellular non-esterified cholesterol and phospholipids are transported by ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) to lipid-poor nascent apolipoprotein for high-density lipoprotein (HDL) assembly. HDL then carries esterified cholesterol back to the liver for excretion.

Two transcripts of ABCA1 utilize separate promoters identified in human and mouse liver, and one transcript was identified in the intestine [35]. Promoter 1 (peripheral-type promoter used in the intestine) is located in the 5′flanking region of the ABCA1 gene, is LXR-responsive, and produces a full-length transcript. Promoter 2 (liver-type promoter) is located in the first intron and gives a shorter transcript that is SREBP-2 responsive. In promoter 1, an LXRE (DR4 element) is also permissive for TR binding. TR competes with LXR for binding to the ABCA1-LXRE and inhibits LXR-mediated Abca1 gene expression [36]. Consistent with this mechanism, T3 treatment in mice decreases serum HDL [37].

Abca1 mRNA is increased in hepatic cells overexpressing SREBP-2 but absent in Srebp-2 null hepatic cells [38]. In the liver, when cholesterol biosynthesis is inhibited by HMG CoA reductase inhibitors, SREBP-2 activates Abca1 (shorter transcript) transcription through promoter 2, which facilitates liver cholesterol efflux. Reduced Abca1 expression results in reduced serum HDL in hyperthyroid rats [37]. Modest reductions in serum HDL has been observed in clinical trials of TR selective agonists [6].

Regulation of Bile Acid Synthesis

Conversion of cholesterol into bile acids is important for maintaining whole body cholesterol homeostasis. The rate-limiting enzyme in bile acid synthesis is cholesterol 7-hydroxylase (CYP7A1). Expression of Cyp7a1 is regulated by several nuclear receptors as well as most likely through a feedback regulation by bile acids [39]. Functional nuclear receptor response elements, TRE, glucocorticoid response element (GRE), LXRE and PPRE have been identified in the promoter of Cyp7a1 of several species, concentrated in the regions referred to as sites I, II and III. Therefore, both human and murine Cyp7a1 are differentially regulated by nuclear receptors and their ligands.

In mice, the Cyp7a1 promoter has two TRE binding sites, I and II. Site I additionally contains a PPRE [40], which is not present in the human site I. Murine site II is 100% homologous among species and contains a TRE, LXRE, glucocorticoid receptor binding element (GRE), hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α HNF4) binding site and PPRE [40]. In TRβ knock-out mice, Cyp7a1 mRNA expression does not respond to T3 stimulation but is markedly induced by cholesterol feeding [23]. In TRβ mutant (Δ337T) mice, a thyroid hormone resistance model, high cholesterol diet induces Cyp7a1 mRNA and bile acid synthesis, suggesting that the mutant TR did not interfere with LXR stimulation [41]. In both cases, LXR is activated by a high cholesterol diet, stimulating Cyp7a1 gene expression and bile acid synthesis, resulting in a net effect of resistance to cholesterol diet-induced hypercholesterolemia. While the mechanism remains unknown for these effects, TR and LXR have a similar affinity for the TRE/LXRE in the Cyp7a1 promoter; therefore, it is possible that competition between unliganded TR and liganded LXR for DNA binding to the site regulates Cyp7a1expression [42].

Cyp7a1gene regulation is different in humans compared to mice. In mice, the bile acid pool consists of mostly hydrophilic acids, whereas the human bile acid pool consists of hydrophobic acids [39], which influences bile acid signaling. Human CYP7A1 expression is most likely regulated via a feedback regulation mechanism known to involve TR, PPAR, farnesoid X receptor (FXR), small heterodimer partner (SHP), HNF4α, and liver-related homologue-1 (LRH-1) [39]. Human CYP7A1 gene also contains two TR binding sites, II and III (−150/−123 and −227/−247), but not site I. TR binding at either site II or III is sufficient to repress the gene expression in the presence of T3 [43]. Indeed, CPY7A1 expression in human hepatocytes is highly sensitive to T3, and treatment with T3 reduces CYP7A1 mRNA and cholic and chenodecoycholic acid synthesis [44]. On the other hand, LXR has little effect on CYP7A1 mRNA levels, and LXR/RXR does not bind to the human CYP7A1 gene promoter or compete with TR [45].

Recently, it was reported that bile acids increase energy expenditure and cyclic-AMP production [9]. Bile acids bind to a G-Protein coupled receptor, TGR5, in brown adipocytes and human skeletal muscle cells, increase D2 activity and stimulate T4 to T3 conversion [9]. This action of bile acids leads to protection from diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. It is likely that bile acids have a role in promoting the increase in T3 levels that increase oxygen consumption and energy expenditure. Increasing T3 concentration inhibits bile acid synthesis and reduces cyclic-AMP production and cyclic-AMP-dependent D2 activity.

The response element for PPAR and HNF4α are also located in site II of the human CYP7A1 promoter. Whereas HNF4α stimulates CYP7A1 gene expression, PPARα strongly inhibits it by inhibiting HNF4α activity [46], thereby suppressing cholesterol elimination from the body by bile salt excretion. However, PPARα agonist reduces cholesterol by improving cholesterol reverse transport and increasing HDL levels [47]. Because the multiple response elements in the promoter are in close proximity, crosstalk between TR and PPARα or HNF4α might occur. Investigation of the mechanism of crosstalk regulation of bile acid synthesis will contribute to understanding the physiological role of ligand effects on cholesterol homeostasis.

Fatty Acid Metabolism

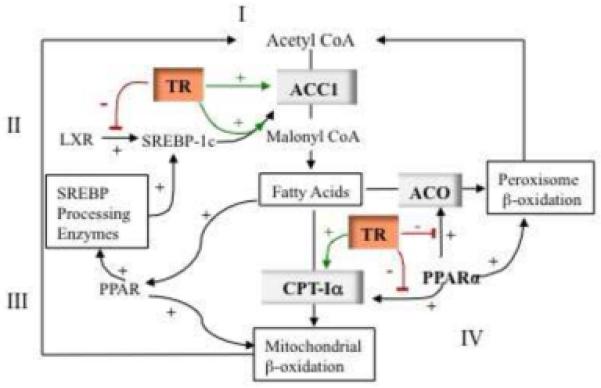

Fatty acid oxidation mobilizes stored triglycerides and generates ATP to meet cellular demands (Figure 2) [11,12]. Regulation of fatty acid oxidation is mainly through key rate limiting enzymes such as carnitine palmitoyltransferase Iα (CPT-Iα) and acyl-CoA oxidase (ACO). CPT-Iα catalyzes the transport of long chain fatty acids from cytosol into mitochondria for β-oxidation. ACO catalyzes the first rate limiting reaction in peroxisome β-oxidation. Both T3 and PPAR modulate CPT-Iα and ACO gene transcription. In fat-fed hamsters, PPARα agonist treatment induced CPT-Iα mRNA and reduced serum triglyceride levels [48]. A functional TRE and CCAAT enhancer binding protein (C/EBP) is required for T3-induction of CPT-Iα [49]. In fact, a PPRE, identical in human and rodent, and a TRE are located in close proximity in the mouse Cpt-Ia promoter [50,51]. In both human and rodent, PPARα-mediated stimulation of CPT-Iα mRNA is enhanced by PPARγ coactivator (PGC)-1 [52]. PGC-1 augments T3-induction of CPT-Iα expression [52].

Figure 2.

Crosstalk Between Thyroid Hormone Signaling and Metabolic Pathways in Fatty Acid Synthesis and β-Oxidation. Fatty acid synthesis and oxidation mobilizes glucose and triglycerides stores, important for thermogenesis and energy homeostasis. (i) Fatty acid synthesis is controlled by the rate limiting enzyme acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC)1. Thyroid hormone increases ACC1 mRNA expression by directly stimulating the ACC1 promoter that contains a thyroid hormone receptor response element (TRE) and sterol regulating element binding protein response element (SRE). (ii) Liver X receptor (LXR) stimulates fatty acid synthesis by enhancing SREBP-1c gene expression. In the absence of T3, TR competes with LXR for DNA binding and inhibits expression of SREBP-1c. (iii) Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)α agonist increases fatty acid synthesis by enhancing sterol regulating element binding protein (SREBP) processing enzymes (insig-1 and −2) and SREBP-1c maturation. (iv) Thyroid hormone increases fatty acid oxidation by upregulating expression of the key mitochondrial β-oxidation enzyme, carnityl palmotoyl transferase (CPT)-Iα. PPARα also stimulates expression of CPT-Iα and promotes fatty acid β-oxidation. Omega-3 long-chain fatty acids are ligands for PPARα. PPARα also stimulates Acyl-CoA oxidase (ACO), a rate limiting enzyme in peroxisomal β-oxidation. Unliganded TR can block stimulation of CPT1α and ACO by PPARα competing for limiting retinoid x receptor (RXR) and by binding to the PPRE.

The crosstalk between PPAR and T3 signals in regulating CPT-Iα has also been demonstrated in studies using a TRα (P398H) mutant mouse model. This mutant TRα occupies the CPT-Iα PPRE and inhibits PPARα-induced Cpt-Ia expression, causing fatty acid accumulation in livers of these mice [53]. However, the interference of mutant TR with PPARα signaling might be specific for the P398H mutation as this was not seen with other TRα mutations [53]. The TRα (R384C) mutant mouse is hypermetabolic, due to enhanced central adrenergic activation, with increased glucose uptake and oxygen consumption in adipocytes and no influence on PPARα stimulation of Cpt-Ia gene expression in fat cells [54]. The TRαPV mutant mouse model has a thyroid hormone resistance-associated frame shift mutation, similar to that reported in a patient with a TRβ mutation introduced into the TRα gene. This mouse model has increased metabolism and impaired adipogenesis, in part due to the TRαPV mutation blocking PPARγ-mediated promotion of adipogenesis [22]. These different metabolic phenotypes in TRα mutant mouse models suggest that metabolic signaling pathways are differentially influenced by the various TRα mutations.

TR and PPARα co-regulate a number of metabolic genes including ACO, ACC, thiolase and malic enzyme [55,56]. In most cases, unliganded TR interferes with PPARα action by competing for the heterodimerization partner RXR. Lipoprotein lipase is regulated by PPARγ and a PPRE has been identified that mediates this action. The TRβ PV mutant heterodimerizes with PPARγ and recruits nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR) to activate histone deacetylases (HDAC), which inhibit PPARγ -mediated lipoprotein lipase gene expression [57]. In general, liganded TR does not interfere with PPARα signaling, and is enhanced in the presence of T3 and PPARα ligand to affect expression of certain genes. The interference of the unliganded TR may act to blunt PPARα pathways when thyroid hormone levels are low.

Thyroid hormone stimulates lipogenesis in the liver. Hepatic production of malonyl-CoA is the rate-limiting step in the synthesis of fatty acids and catalyzed by both ACC1 and 2. ACC1 is enriched in the liver and other lipogenic tissues and is regulated by TR, LXR and SREBP-1 at the transcriptional level through the ACC1 promoter II [58]. SREBP-1 enhances ACC1 mRNA expression by forming a tetrameric complex with TR/RXR, which stabilizes SREBP-1 on its binding site [59]. A PPARα agonist stimulates ACC1 gene expression by enhancing the expression of SREBP-1c processing enzymes, which increases nuclear SREBP-1c activity [60]. LXR directly stimulates ACC1 gene expression [61,62]. Although thyroid hormone directly stimulates several enzymes important in lipogenesis, some genes are regulated by TR complexed with other factors.

Lipogenesis in the breast is influenced by a carbohydrate-stimulated and T3-stimulated protein, spot 14 (now referred to as Thrsp) [63]. The phenotype of the Thrsp knockout mouse varies depending on the gene inactivation approach and strain [63], but a recent report showed that Thrsp knockout mice have marked deficiencies in lipogenesis in the lactating mammary gland and resistance to diet-induced obesity [64]. The strong induction of Thrsp by T3, and association with lipogenesis and obesity, suggests that Thrsp is a promising signaling pathway to link body weight and thyroid status.

Glucose Metabolism

The liver in hyperthyroid patients has reduced insulin sensitivity. There is increased expression of aceteyl CoA carboxylase, reduced malonyl CoA and increased expression of CPT-1 [12]. Synthesis of malonyl-CoA allosterically inhibits CPT-I and increases glucose-induced insulin secretion, so reduced expression is associated with insulin resistance [65]. In the energy conserving mode, low T3 or diabetes, ACC1 gene expression and activity is reduced, resulting in less malonyl CoA and reduced insulin secretion. Refeeding with a carbohydrate-rich diet, T3 treatment, or insulin treatment induces ACC1 gene expression, thereby increasing fatty acid synthesis and glucose utilization. This shows a relationship between lipid synthesis and insulin secretion, influenced by thyroid status.

Recently, D-glucose and D-glucose-phosphate were found to be direct agonists of LXRα and LXRβ, indicating that LXR might integrate glucose and fatty acid metabolism [66]. These findings identify another area for potential co-regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism through TR/T3 and LXR/agonist (glucose and oxysterols) crosstalk in regulating metabolic homeostasis [67].

Hyperthyroidism is associated with impaired glucose tolerance and insulin resistance [12]. Although the metabolic changes associated with hyperthyroidism generally raise glucose, there are some actions of thyroid hormone that may increase insulin sensitivity. Thyroid hormone reduces body fat and increases mitochondrial oxidative metabolism in skeletal muscle, two features defective in insulin resistance and Type 2 diabetes [6,12]. In an animal study, treatment of leptin-deficient ob/ob mice with a TRβ selective agonist reduced plasma glucose [12]. A patient with diabetes due to an insulin receptor defect was evaluated for activation of BAT and glucose control when taken off thyroid hormone in connection with thyroid cancer treatment [68]. In the hypothyroid state, the patient had less BAT and deteriorated glucose control compared to these parameters when euthyroid [68]. The glucose metabolism response to thyroid hormone likely varies among tissues, as well as in response to TR interactions with other nuclear receptors and factors. Positive effects of thyroid hormone on mitochondrial oxidation and BAT activation may have a beneficial effect on glucose control in some diabetics.

Hepatic Steatosis

Hepatic steatosis is observed in several animal models with inactivation of various nuclear receptors involved in metabolic control, including PPARα and the P398H TRα mutant [53]. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome are associated with lipid deposition in the liver, which in susceptible patients can lead to fibrosis and even cirrhosis [69]. A recent study profiled gene expression in human livers with steatosis compared to normal livers [70]. Among a large number of genes that were profiled, the greatest change in liver gene expression as a consequence of fat deposition compared to control, was downregulation of a set of T3-responsive genes. This set of genes was originally identified as T3-responsive in skeletal muscle and includes genes involved in energy metabolism, protein catabolism, and RNA metabolism. In related animal studies, treatment with T3 or with a TRβ-selective analog with high penetration in the liver [71], or with activation in the liver by P450 3A [72], reversed hepatic steatosis. These findings suggest that targeted stimulation of lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation in the liver has significant therapeutic promise [69].

Future Questions

Thyroid hormone is a clearly established modulator of multiple metabolic signaling pathways. In humans, hypothyroidism is associated with hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, weight gain, and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, indicating the physiological importance of this modulation [2]. These actions of thyroid hormone have made isoform-selective TR agonists highly attractive targets for drug development, and trials with these agents show great promise [6]. The usual experience with nuclear receptor agonists, however, is unanticipated actions of these ligands on other pathways [73]. It is important that the mechanisms of interactions of TR with these other metabolic regulators be investigated to identify the range of potential interactions and optimize the therapeutic effects of agents that target these pathways.

Future studies should determine the respective role(s) of TR and ligand, and the variability of interaction with different gene targets and in different tissues. The most significant challenge will be to develop and use model systems that reflect these interactions under physiological conditions, such as with changes in nutrient intake, ambient temperature, circadian rhythms, and activity levels. Under conditions that require energy conservation, such as fasting, thyroid hormone modulation might be especially important. Because unliganded TR is associated with repression of positively regulated genes, the effects of reduced ligand are amplified by not only the absence of simulation, but also by the repression of genes normally activated by T3.

Regulation of circulating thyroid hormone and T3 availability at the local tissue level is a critical step in metabolic control. Nutritional status feedback at the level of the hypothalamus influences the TRH set-point and the resulting circulating thyroid hormone levels. Bile acids directly stimulate D2 that converts the prohormone T4 to T3. The potential for nutritional status and nutrient intake to influence ligand availability should be evaluated in any model system.

We are at the early stages of understanding the mechanisms and significance of crosstalk physiologically and pharmacologically between TR and other nuclear receptor pathways. Understanding these interactions will help manage current targeted therapies as well as developing new therapies and combinations for metabolic disorders.

Acknowledgements

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant RO1 DK67233 to GB.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Oetting A, Yen PM. New insights into thyroid hormone action. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;21:193–208. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein I, Danzi S. Thyroid disease and the heart. Circulation. 2007;116:1725–1735. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hollenberg AN. The role of the thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) neuron as a metabolic sensor. Thyroid. 2008;18:131–139. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox CS, et al. Relation of thyroid function to body weight. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008;168:587–592. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.6.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenta G, et al. Potential therapeutic applications of thyroid hormone analogs. Nat. Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;3:632–640. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baxter JD, Webb P. Thyroid hormone mimetics: potential applications in atherosclerosis, obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2009;8:308–320. doi: 10.1038/nrd2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Araki O, et al. Distinct dysregulation of lipid metabolism by unliganded thyroid hormone receptor isoforms. Mol. Endocrinol. 2009;23:308–315. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gereben B, et al. Cellular and molecular basis of deiodinase-regulated thyroid hormone signaling. Endocr. Rev. 2008;29:898–938. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe M, et al. Bile acids induce energy expenditure by promoting intracellular thyroid hormone activation. Nature. 2006;439:484–489. doi: 10.1038/nature04330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim B. Thyroid hormone as a determinant of energy expenditure and the basal metabolic rate. Thyroid. 2008;18:141–144. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silva JE, Bianco SD. Thyroid-adrenergic interactions: physiological and clinical implications. Thyroid. 2008;18:157–165. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crunkhorn S, Patti ME. Links between thyroid hormone action, oxidative metabolism, and diabetes risk? Thyroid. 2008;18:227–237. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu YY, et al. A thyroid hormone receptor α gene mutation (P398H) is associated with visceral adiposity and impaired catecholamine-stimulated lipolysis in mice. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38913–38920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306120200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ribeiro MO, et al. Thyroid hormone-sympathetic interaction and adaptive thermogenesis are thyroid hormone receptor isoform-specific. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:97–105. doi: 10.1172/JCI12584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ribeiro MO, et al. Expression of uncoupling protein 1 in mouse brown adipose tissue is thyroid hormone receptor β isoform-specific and required for adaptive thermogenesis. Endocrinology. 2010 doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0667. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiamolera MI, Wondisford FE. Minireview: Thyrotropin-releasing hormone and the thyroid hormone feedback mechanism. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1091–1096. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potenza M, et al. Excess thyroid hormone and carbohydrate metabolism. Endocr. Pract. 2009;15:254–262. doi: 10.4158/EP.15.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugden MC, Holness MJ. Role of nuclear receptors in the modulation of insulin secretion in lipid-induced insulin resistance. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008;36:891–900. doi: 10.1042/BST0360891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holness MJ, et al. PPARα activation and increased dietary lipid oppose thyroid hormone signaling and rescue impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in hyperthyroidism. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008;295:1380–1389. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90700.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hashimoto K, et al. Carbohydrate response element binding protein gene expression is positively regulated by thyroid hormone. Endocrinology. 2009;150:3417–3424. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oppenheimer JH, et al. Functional relationship of thyroid hormone-induced lipogenesis, lipolysis, and thermogenesis in rat. J. Clin. Invest. 1991;87:125–132. doi: 10.1172/JCI114961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ying H, et al. Impaired adipogenesis caused by a mutated thyroid hormone α1 receptor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:2359–2371. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02189-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gullberg H, et al. Thyroid hormone receptor beta-deficient mice show complete loss of the normal cholesterol 7 α-hydroxylase (CYP7A) response to thyroid hormone but displays enhanced resistance to dietary cholesterol. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1739–1749. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.11.0548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erion MD, et al. Targeting thyroid hormone receptor-β agonists to the liver reduces cholesterol and triglycerides and improves the therapeutic index. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:15490–15495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702759104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shulman AI, Mangelsdorf DJ. Retinoid x receptor heterodimers in the metabolic syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:604–615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Q, et al. Fatty acyl-CoAs are potent inhibitors of the nuclear thyroid hormone receptor in vitro. J. Biochem. 1990;107:699–702. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Juge-Aubry CE, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor mediates cross-talk with thyroid hormone receptor by competition for retinoid X receptor. Possible role of a leucine zipper-like heptad repeat. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:18117–18122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.18117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shin DJ, Osborne TF. Thyroid hormone regulation and cholesterol metabolism are connected through Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein-2 (SREBP-2) J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:34114–34118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305417200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hashimoto K, et al. Mouse sterol response element binding protein-1c gene expression is negatively regulated by thyroid hormone. Endocrinology. 2006;147:4292–4302. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bengoechea-Alonso MT, Ericsson J. SREBP in signal transduction: cholesterol metabolism and beyond. Curr. Opin. Cell. Biol. 2007;19:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y, et al. SREBP-1 integrates the actions of thyroid hormone, insulin, cAMP, and medium-chain fatty acids on ACCα transcription in hepatocytes. J. Lipid. Res. 2003;44:356–368. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200283-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lopez D, et al. Activation of the hepatic LDL receptor promoter by thyroid hormone. Biochimica. et. Biophysica. Acta. 2007;1771:1216–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldstein JL, et al. Protein sensors for membrane sterols. Cell. 2006;124:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Konig B, et al. Activation of PPARα lowers synthesis and concentration of cholesterol by reduction of nuclear SREBP-2. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2007;73:574–585. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamehiro N, et al. Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-2- and liver X receptor-driven dual promoter regulation of hepatic ABC transporter A1 gene expression: mechanism underlying the unique response to cellular cholesterol status. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:21090–21099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701228200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huuskonen J, et al. Regulation of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 transcription by thyroid hormone receptor. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1626–1632. doi: 10.1021/bi0301643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tancevski I, et al. Reduced plasma high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in hyperthyroid mice coincides with decreased hepatic adenosine 5′-triphosphate-binding cassette transporter 1 expression. Endocrinology. 2008;149:3708–3712. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong J, et al. SREBP-2 positively regulates transcription of the cholesterol efflux gene, ABCA1, by generating oxysterol ligands for LXR. Biochem. J. 2006;400:485–491. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chiang JY. Bile acids: regulation of synthesis. J. Lipid. Res. 2009;50:1955–1966. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R900010-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheema SK, Agellon LB. The murine and human cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase gene promoters are differentially responsive to regulation by fatty acids mediated via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:12530–12536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.17.12530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hashimoto K, et al. Cross-talk between thyroid hormone receptor and liver X receptor regulatory pathways is revealed in a thyroid hormone resistance mouse model. J Biol. Chem. 2006;281:295–302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507877200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawai K, et al. Unliganded thyroid hormone receptor-beta1 represses liver X receptor alpha/oxysterol-dependent transactivation. Endocrinology. 2004;145:5515–5524. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drover VA, et al. A distinct thyroid hormone response element mediates repression of the human cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) gene promoter. Mol. Endocrinol. 2002;16:14–23. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.1.0751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ellis EC. Suppression of bile acid synthesis by thyroid hormone in primary human hepatocytes. World. J. Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4640–4645. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i29.4640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Agellon LB, et al. Dietary cholesterol fails to stimulate the human cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase gene (CYP7A1) in transgenic mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:20131–20134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patel DD, et al. The effect of peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor-alpha on the activity of the cholesterol 7 alpha-hydroxylase gene. Biochem. J. 2000;351:747–753. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duffy D, Rader DJ. Emerging therapies targeting high-density lipoprotein metabolism and reverse cholesterol transport. Circulation. 2006;113:1140–1150. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.593855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Minnich A, et al. A potent PPARα agonist stimulates mitochondrial fatty acid beta-oxidation in liver and skeletal muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;280:E270–279. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.2.E270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jackson-Hayes L, et al. A thyroid hormone response unit formed between the promoter and first intron of the carnitine palmitoyltransferase-Iα gene mediates the liver-specific induction by thyroid hormone. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:7964–7972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Louet JF, et al. Regulation of liver carnitine palmitoyltransferase I gene expression by hormones and fatty acids. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2001;29:310–316. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Napal L, et al. An intronic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-binding sequence mediates fatty acid induction of the human carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;354:751–759. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Y, et al. Peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1 alpha (PGC-1 alpha) enhances the thyroid hormone induction of carnitine palmitoyltransferase I (CPT-I alpha) J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:53963–53971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406028200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu YY, et al. A mutant thyroid hormone receptor alpha antagonizes peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha signaling in vivo and impairs fatty acid oxidation. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1206–1217. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sjogren M, et al. Hypermetabolism in mice caused by the central action of an unliganded thyroid hormone receptor alpha1. EMBO J. 2007;26:4535–4545. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang Y, et al. Thyroid hormone stimulates acetyl-coA carboxylase-alpha transcription in hepatocytes by modulating the composition of nuclear receptor complexes bound to a thyroid hormone response element. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:974–983. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005894200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chu R, et al. Thyroid hormone (T3) inhibits ciprofibrate-induced transcription of genes encoding beta-oxidation enzymes: cross talk between peroxisome proliferator and T3 signaling pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:11593–11597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Araki O, et al. Thyroid hormone receptor beta mutants: Dominant negative regulators of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:16251–16256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508556102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang C, Freake HC. Thyroid hormone regulates the acetyl-CoA carboxylase PI promoter. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1998;249:704–708. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yin L, et al. Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 interacts with the nuclear thyroid hormone receptor to enhance acetyl-CoA carboxylase-alpha transcription in hepatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:19554–19565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111771200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Knight BL, et al. A role for PPARα in the control of SREBP activity and lipid synthesis in the liver. Biochem. J. 2005;389:413–421. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Talukdar S, et al. Chenodeoxycholic acid suppresses the activation of acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase-alpha gene transcription by the liver X receptor agonist T0-901317. J. Lipid. Res. 2007;48:2647–2663. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700189-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cha JY, Repa JJ. The liver X receptor (LXR) and hepatic lipogenesis. The carbohydrate-response element-binding protein is a target gene of LXR. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:743–751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605023200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.LaFave LT, et al. Minireview: S14: insights from knockout mice. Endocrinology. 2006;147:4044–4047. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anderson GW, et al. The Thrsp null mouse (Thrsp tm1cnm) and diet-induced obesity. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2009;302:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roduit R, et al. A role for the malonyl-CoA/long-chain acyl-CoA pathway of lipid signaling in the regulation of insulin secretion in response to both fuel and nonfuel stimuli. Diabetes. 2004;53:1007–1019. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.4.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mitro N, et al. The nuclear receptor LXR is a glucose sensor. Nature. 2007;445:219–223. doi: 10.1038/nature05449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lazar MA, Wilson TM. Sweet dreams for LXR. Cell Metab. 2007;5:159–161. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Skarulis MC, et al. Thyroid hormone induced brown adipose tissue and amelioration of diabetes in a patient with extreme insulin resistance. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010 doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0543. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Arrese M. Burning hepatic fat: therapeutic potential for liver-specific thyromimetics in the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;49:348–352. doi: 10.1002/hep.22783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pihlajamaki J, et al. Thyroid hormone-related regulation of gene expression in human fatty liver. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;94:3521–3529. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Perra A, et al. Thyroid hormone (T3) and TRβ agonist GC-1 inhibit/reverse nonalcoholic fatty liver in rats. FASEB J. 2008;22:2981–2989. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-108464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cable EE, et al. Reduction of hepatic steatosis in rats and mice after treatment with a liver-targeted thyroid hormone receptor agonist. Hepatology. 2009;49:407–417. doi: 10.1002/hep.22572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grundy SM. Thyroid mimetic as an option for lowering low-density lipoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:409–410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705959104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]