Abstract

HIV-1 prevalence is highest in developing countries; similarly helminth parasites are often highly endemic in these same areas. Helminths are strong immune modulators, and negatively impact the ability of the infected hosts to mount protective vaccine specific T cell immune responses for HIV-1 and other pathogens. Indeed, previously we found that Schistosoma mansoni infected mice had significantly impaired HIV-1C vaccine specific T cell responses. Anthelminthics are available and inexpensive; therefore, in this study, we evaluated whether elimination of schistosome infection prior to vaccination with an HIV-1C DNA vaccine would increase recipients vaccine specific responses. As expected, splenocytes from S. mansoni infected mice produced significantly elevated amounts of interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-10, and significantly lower amounts of interferon (IFN)-γ than splenocytes from naïve mice. Following elimination of parasites by praziquantel (PZQ) treatment, splenomegaly was significantly reduced, though splenocytes produced similar or higher levels of IL-10 than splenocytes from infected mice. However, we found that PZQ treatment significantly increased levels of IFN-γ in response to Concanavalin A or SEA compared to splenocytes from untreated mice. Importantly, PZQ treatment resulted in complete restoration of HIV-1C vaccine specific T cell responses at 8 weeks post PZQ treatment. Restoration of HIV-1C vaccine specific T cell responses following elimination of helminth infection was time dependent, but surprisingly independent of the levels of IL-4 and IL-10 induced by parasite antigens. Our study shows that elimination of worms offers an affordable and a simple means to restore immune responsiveness to T cell based vaccines for HIV-1 and other infectious diseases in helminth endemic settings.

Keywords: HIV-1 vaccine, Multi-CTL-epitopes, praziquantel, Helminth, Schistosome

1. Introduction

HIV-1 continues to be a worldwide public health challenge twenty-five years after HIV-1 was identified [1–3]. According to a 2008 report on the global AIDS epidemic issued by United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the World Health Organization (WHO), there are approximately 33 million people living with HIV-1/AIDS globally [4]. The AIDS epidemic is most devastating in developing countries, particularly sub-Saharan Africa. Approximately two thirds (64%) of all people living with HIV are in sub-Saharan Africa, where HIV/AIDS has reduced life expectancy, slowed economic growth and increased poverty [4]. Two decades of research on anti-retroviral therapy has advanced such that highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) can be employed to dramatically reduce HIV related mortality and morbidity as well as mother-to-child transmission [5].

Despite a massive research effort and expense, there is no vaccine available for HIV-1. Nonetheless, there is strong evidence that a vaccine against HIV-1 is an achievable goal [6,7], and considerable effort is ongoing to develop a protective vaccine that elicits HIV-1-specific immune responses. The majority of HIV-1 vaccines that are in, or about to enter clinical trials, are designed to induce cellular immunity to target and kill HIV-infected cells [7–11]. Once successful HIV-1 vaccine(s) are developed, they will be administered to developing country populations, where HIV is most devastating. Several factors must be considered when developing and testing HIV vaccines for developing country populations. An important factor is that the majority of individuals living in sub-Saharan Africa and other developing countries are infected with one or more helminth parasites [12–16], with prevalence exceeding 90% in many areas of Africa. Patients infected with helminth parasites have CD4+ T cell bias skewed towards T-helper type 2 (Th2), as well as expanded T regulatory cell populations and some level of immune suppression/anergy [17–30]. Thus, HIV-1 vaccines likely will not generate reasonable vaccine-specific Th1-type and cytotoxic T-cell responses in helminth infected recipients. This is based on results from earlier studies demonstrating that helminth infection significantly impaired Th1-type vaccine specific immune responses to bacterial and viral vaccines in humans and animal models [31–37]. Further, we observed that Schistosoma mansoni infection significantly suppressed vaccine specific T cell responses to an HIV-1C T cell based DNA vaccine in mice [37].

Helminth induced immune suppression is dependent on live and viable parasites, and elimination of these parasites results in the recovery of immune responsiveness [36,38]. Therefore, in this study, we investigated whether elimination of schistosome infection, prior to vaccine administration, would allow recipients to mount vaccine specific immune responses. We used the multi-epitope T cell based vaccine for HIV-1C designated Igκ-TD158 [37]. The Igκ-TD158 vaccine construct contains the murine specific CTL epitope, P18 at the 3′-end of the vaccine [37,39]. P18 is an immunodominant epitope derived from the V3 loop of HIV-1 gp120 (RIQRGPGRAFVTIGK) and restricted by the H-2Dd MHC-I molecule [39]. To mimic likely scenarios of patients in developing countries, we vaccinated naïve mice, schistosome-infected mice and schistosome-infected then praziquantel (PZQ) treated mice with the Igκ-TD158 DNA vaccine construct. The goal was to determine if elimination of helminth infection would restore vaccine responsiveness, and examine if restoration was dependent on time post PZQ treatment, or on reduction of the levels of IL-4 and IL-10. We found that PZQ treatment significantly restored the ability of infected mice to mount strong vaccine specific T cell immune responses at 4 weeks post PZQ treatment, with complete restoration of vaccine specific immune responses at 8 weeks post treatment. These results show that elimination of helminth infection prior to vaccination with T cell based vaccines is essential to successfully vaccinate individuals in helminth endemic settings. Surprisingly, the levels of IL-10 were elevated in splenocytes from mice treated with PZQ 4 or 8 weeks previously. Thus, levels of IL-10 in helminth infected, or helminth infected and PZQ-treated recipients, are independent and not predictive of immune status of the host for T cell based vaccines. This finding suggests that there are other regulatory factors or cells, which play important roles in suppression of vaccine specific immune responses in helminth infected individuals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mice and parasites

Female, 6–8 weeks old BALB/c mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions at the Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH) animal facility. Mice were used following HSPH guidelines and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocols.

Biomphalaria glabrata snails, infected with S. mansoni (Puerto Rican strain) were obtained from the Biomedical Research Institute, Rockville, MD, USA, and maintained in our laboratory. Infectious larvae, cercariae, were prepared by exposing infected snails to light for 1 h to induce shedding. Cercarial numbers and viability were determined using a light microscope.

2.2. Plasmid DNA and peptides

The multi-epitope T cell DNA vaccine for HIV-1 subtype C designated Igκ-TD158 was used to immunize mice. The immunodominant epitopes, the design and the construction of this vaccine were previously described [37]. The Igκ-TD158 construct contains two known monkey CTL epitopes restricted by MamuA01 (P11C, ACTPYDINQML) [40] and MamuA08 (P9CD, KPCVKLTP) [41] and one known murine CTL epitope restricted by MHC class I, H-2Dd (P18, RIQRGPGRAFVTIGK) [39] as marker epitopes to facilitate immunogenicity studies in rhesus macaques and mice.

The 10-mer P18-I10 (RGPGRAFVTI), an H-2Dd-restricted peptide, was synthesized by Biosynthesis Inc. (Lewisville, TX, USA). The peptide was HPLC purified (>95% purity) and analyzed by Mass Spectrometry. P18-I10 peptide was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), aliquoted and stored at −80°C. The peptide was diluted in culture medium just before use.

2.3. Infection with S. mansoni, PZQ treatment and DNA immunization

Groups of female BALB/c mice were maintained as naïve (un-infected) or infected with S. mansoni. For infection, mice were exposed to 50 cercariae by abdominal skin penetration as previously described [42]. Nine weeks after infection, immune bias toward Th2 type was measured (see below). Ten weeks post infection, half of the infected mice were treated with praziquantel (PZQ) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) and the other half remained infected. Animals were treated with two doses of PZQ (500 mg/kg) administered on day 1 and day 3 by oral gavage. Four and 8 weeks post PZQ treatment, immune responses and CD4+ T cell bias were evaluated in a subgroup of mice (4 mice/group). Immunization with Igκ-TD158 HIV-1C T cell DNA vaccine or the control plasmid pVAX was started at 4 or 8 weeks after PZQ treatment. Mice were immunized intramuscularly (100 μg/injection, 50 μg in each quadriceps; final volume 100 μl) with pVAX or Igκ-TD158 plasmid as previously described [37]. Four weeks later, mice were boosted with 100 μg plasmid DNA in a similar manner. Two weeks after the second injection, vaccine specific T-cell immune responses were analyzed as described below. Infection was confirmed at the time of sacrifice by examining mice for the presence of worms, liver eggs and splenomegaly. The experimental design is summarized in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Experimental design: Infection and immunization protocol. Groups of BALB/c mice were infected with S. mansoni or remained un-infected (control). Ten weeks post infection (wk. 10), half of the infected mice were treated with PZQ (PZQ-Rx). In one set of experiments, mice were primed with Igκ-TD158 or pVAX plasmid DNA vaccines 4 weeks post PZQ treatment (wk. 14); in a second set of experiments, mice were primed 8 weeks post PZQ treatment (wk. 18). Four weeks after DNA prime, mice were boosted in a similar manner. Two weeks later mice were sacrificed and the HIV-1C vaccine specific T cell responses were determined by IFN-γ ELISPOT as described under Materials and Methods (at this point, at least 8 mice/group were used). The effect of schistosome infection on biasing the mice immune responses toward Th2 was determined at 9 weeks post infection (wk. 9) as well as at 4 and 8 weeks post PZQ treatment (wk. 14 and wk. 18).

2.4. Analysis of Th2 bias induced by schistosome infection

The ability of S. mansoni to bias the host immune response towards Th2 type was measured by ELISA 9 weeks post-infection. Briefly, spleens (4 spleens/group) were isolated from naïve mice or mice infected for 9 weeks. Using standard methodology, single cell suspensions from individual spleens were prepared and red blood cells lysed using Boyle’s reagent. Splenocytes were counted using a Coulter Counter Z1 (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA), and plated in duplicate in 24 well-plates at 1.5 X 106 cells/ml (final volume 1 ml) in RPMI-1640 containing 10% FBS, 2 mM L-Glutamine, 50 μM 2-Mercaptoethanol, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Cells were stimulated with media, SEA (25 μg/ml), or Concanavalin A (Con A, 1 μg/ml) for 72 hours then cytokine levels in culture supernatants determined by ELISA.

The effect of PZQ treatment on the systemic immune response in schistosome-infected mice was determined. Spleens were isolated from naïve mice, schistosome infected mice, and schistosme infected then PZQ treated mice (4 weeks and 8 weeks post PZQ-Rx). Splenocytes were prepared and stimulated as described above, and cytokine levels in culture supernatants determined by ELISA.

2.5. ELISA

Splenocyte culture supernatants from individual mice were collected and the levels of IL-4, IL-10 and IFN-γ determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) using the BD OptEIA Mouse cytokine ELISA Sets according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB)/hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was used as a substrate and reactions stopped by the addition of 5% phosphoric acid to all wells. Optical densities (OD450 nm) were measured using a Spectra Max 190 ELISA plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Cytokine concentrations were calculated by using standard curves created on each plate with known amounts of recombinant cytokines.

2.6. Analysis of HIV-1C vaccine T-cell responses

Two weeks after the second immunization, mice were sacrificed, spleens were collected from individual mice and splenocytes prepared using standard methodology (See above), and counted using a Coulter Counter Z1 (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA). The frequency of IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells was determined by IFN-γ ELISPOT assay as previously described [37]. Briefly, 96-well HTS Immunospot™ Elispot plates (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) were pre-wetted with 15 μl of 35% ethanol and washed 3 times with distilled water and one time with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Plates were then coated overnight at 4°C with 100 μL/well of 15 μg/mL anti-IFN-γ antibody solution (clone AN18; Maptech Inc., Mariemont, OH, USA). After 3 washes with PBS, plates were blocked with culture medium (RPMI-1640) containing 10% FBS for 2 h at room temperature. Splenocytes from individual mice were plated in triplicate at densities of 3×105 and 1.5×105 cells/well, then stimulated with RPMI or 20 μM of P18-I10 and incubated at 37°C for 20 h. As a positive control, cells were stimulated with 1 ng/mL Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) and 1 μM ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Twenty hours later, cells were washed off, then plates were washed four times with PBS followed by the addition of 100 μL of 1μg/mL biotinylated anti-IFN-γ antibody (clone R4-6A2, Maptech) to each well. Following overnight incubation at 4°C, plates were washed 5 times with PBS, then 100 μL of 1:1000 Streptavidin-HRP (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) were added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 1 hr. Plates were then washed with PBS, and 100 μL of the AEC substrate (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA) added to each well. After color development, plates were washed several times with distilled water and air dried overnight at room temperature. Spots were counted and analyzed using an ImmunoSpot™ Analyzer (Cellular Technology Ltd. C.T.L., OH). Data is presented as spot forming colonies (SFC) per million splenocytes. SFCs were calculated using both cell densities for each of individual animals within the group and presented as means plus/minus standard errors (mean ± SEM).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Results were analyzed for significance using two-tailed Student t-test. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Significant differences (p < 0.05) are indicated with an asterisk.

3. Results

3.1. Schistosome infection biases the host immune response toward Th2 type

In order to mimic the situation found in helminth endemic areas, we immunized mice chronically infected with S. mansoni. To test for schistosome-induced Th2 bias, we tested systemic immune responses of naïve and schistosome infected mice 9 weeks post infection. As shown in Figure 2, splenocytes from schistosome infected mice stimulated with soluble schistosome egg (SEA) or Con A, produced significantly higher levels (p<0.00001) of IL-4 (Fig. 2A–B) and IL-10 (Fig. 2C–D) than splenocytes from naïve mice. Conversely, Con A stimulated splenocytes from schistosome infected mice produced significantly lower levels of IFN-γ compared to splenocytes from un-infected mice (Fig. 2F). This shows that schistosome infection induced Th2 type immune responses as well as increased levels of the immune suppressive cytokine IL-10.

Fig. 2.

S. mansoni infection induces a strong Th2 bias. Spleens were isolated from naïve or 9 weeks infected mice (4 mice/group). Splenocytes were prepared and stimulated with 25 μg/ml SEA (A, C, & E) or 1 μg/ml Con A (B, D, & F) for 72 hr. Levels of IL-4 (A–B), IL-10 (C-D) and IFN-γ (E–F) were determined in culture supernatants by ELISA. This experiment was repeated at least 3 times. * indicates that the differences in cytokines levels between naïve and infected mice are statistically significant (Student’s t-test, p< 0.000001).

3.2. Elimination of schistosome infection elevates IFN-γ production but it does not reduce IL-10

The goal here was to determine if eliminating schistosome infection would restore normal Th1-Th2 immune bias and vaccine responsiveness in previously infected mice. To determine this we stimulated splenocytes from naïve, infected or infected then PZQ treated mice (4 and 8 weeks post PZQ treatment) with SEA and Con A (Figure 3). We found that splenocytes from mice treated with PZQ 8 weeks previously actually produced increased levels of IL-4 following SEA stimulation compared to splenocytes from schistosome infected mice (Fig. 3A). In contrast, Con A stimulated splenocytes collected 4 and 8 weeks post PZQ treatment, had significantly reduced levels of IL-4 production compared with splenocytes from schistosome infected mice (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Effect of PZQ treatment on host immune response. The ability of PZQ treatment to affect cytokine production by splenocytes was determined as described under Materials and Methods, and as outlined in Figure 1. Spleens were obtained from age-matched control (naïve) mice, schistosome-infected mice (infected; hatched bars (14 weeks post infection) and solid bars (18 weeks post infection)), and schistosome-infected then PZQ-treated mice (PZQ-Rx; Praziquantel was administered at 10 weeks after infection, and the immune responses were determined 4 weeks (hatched bard) or 8 weeks (solid bard) after treatment). Splenocytes (4 mice/group) were prepared and stimulated with 25 μg/ml SEA (A, C, & E) or 1 μg/ml Con A (B, D, & F) for 72 hr. Levels of IL-4 (A-B), IL-10 (C-D) and IFN-γ (E–F) were determined in culture supernatants by ELISA. Data is a representative of at least two separate experiments. * indicates that the differences in cytokines levels between PZQ-Rx and infected mice at the same time point are significant as determined with two-tailed Student’s t-test (p<0.001).

Interestingly, IL-10 production was slightly but significantly increased after PZQ treatment whether splenocytes were stimulated with SEA or Con A (Fig. 3C–D). Similar to the IL-10 results, splenocytes from PZQ treated mice stimulated with SEA or Con A produced significantly higher levels of IFN-γ than splenocytes from infected mice (Fig. 3E–F). Further, no significant difference in splenocyte IFN-γ levels was observed in cells from mice at 4 or 8 weeks post PZQ treatment. These data suggest that elimination of schistosomes partially restored normal immune bias as measured by ConA stimulation, resulting in elevated production of IFN-γ and lower production of IL-4.

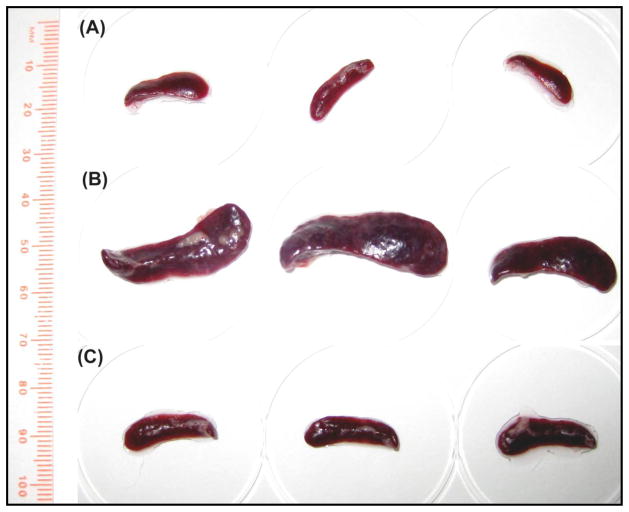

3.3. PZQ treatment improves health and pathology of infected mice

PZQ treatment resulted in substantial improvement in health and pathology of mice. Figure 4 shows a representative image of three spleens obtained from naïve mice (Fig. 4A), 18 week infected mice (Fig. 4B) and 8 week post PZQ treatment (treatment at 10 weeks post infection) (Fig. 4C). As expected, schistosome infection induced splenomegaly (Fig. 4B), with PZQ treatment significantly reducing spleen size to near normal.

Fig. 4.

PZQ treatment significantly reduced splenomegaly. A representative image of spleens isolated from age-matched naïve mice (A), 18 weeks infected mice (B) (low infection, average of 50 cercariae/mouse), or 8 weeks post PZQ treatment (C), PZQ was administered 10 weeks after infection.

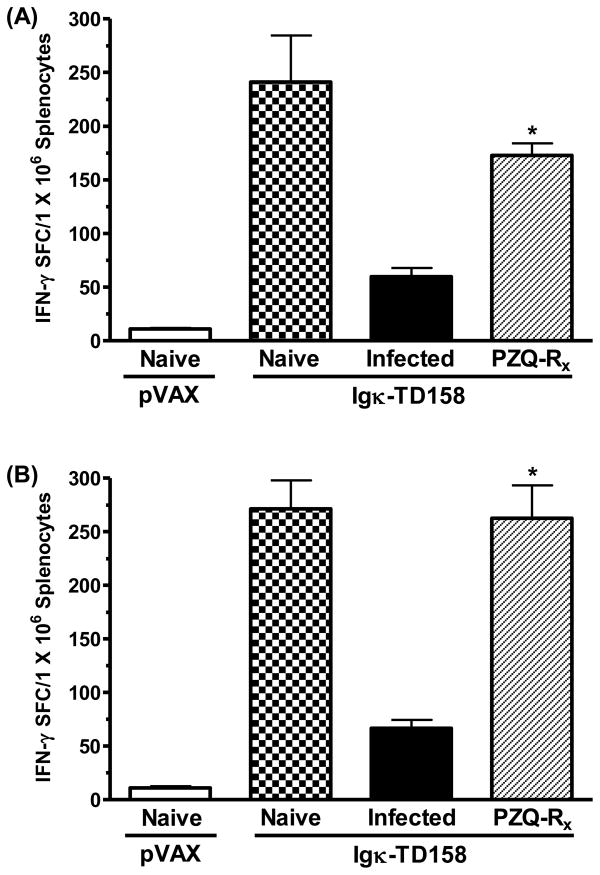

3.4. PZQ treatment restores the HIV-1C vaccine-specific T cell immune responses

We previously demonstrated that schistosome infection significantly suppressed HIV-1C vaccine-specific T cell responses [37]. Therefore, the main goal of this study was to investigate whether elimination of schistosome infection prior to vaccination could restore those responses. To answer this question, we vaccinated naïve mice, schistosome-infected mice, and schistosome-infected then PZQ-treated mice with Igκ-TD158. Immunization of all groups was initiated 4 or 8 weeks post PZQ treatment. Four and 8 week time points were chosen to determine the kinetics of restoration of CD4+ normal bias and vaccine-specific T cell responses. Splenocytes were prepared from mice two weeks post-booster injection and tested for levels of P18-I10 (MHC class I H2Dd restricted epitope) specific IFN-γ producing T cells. As previously shown, schistosome infection significantly reduces the frequency of IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells compared to Igκ-TD158 vaccinated otherwise naïve mice (Figure 5). In preliminary studies, we determined that immunization of mice 4 weeks post PZQ treatment significantly enhanced the frequency of IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells, yet the restoration of HIV-1C vaccine T cell immune response was not complete. Therefore, in this study, we repeated the experiment using a larger number of mice per group (8–12 mice/group) and tested the ability of PZQ treatment to restore HIV-1C vaccine specific T cell responses. As shown in Figure 5A, vaccination of mice 4 weeks after PZQ treatment (hatched bars) significantly increased the frequency of IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells compared to infected mice (solid bars; p<0.000001). However, the frequency of IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells in PZQ treated mice remained lower than the numbers seen in Igκ-TD158 vaccinated naïve mice (Fig. 5A, dotted bars). In the preliminary experiments, the difference in frequency of IFN-γ producing cells between naïve and PZQ treated mice was significant (p<0.05). However, here, where we used larger numbers of mice (8–12 mice/group), that difference was statistically not significant (p<0.066). It is noteworthy that though the difference in frequency of IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells was not significant between naïve and PZQ treated mice (4 weeks post PZQ Rx), the frequency of IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells in PZQ treated mice was always lower than in naïve mice. To determine if additional time post-PZQ treatment would further restore normal immune bias and increase vaccine-specific T cell responses, we waited an additional four weeks prior to mice vaccination. Figure 5B shows that splenocytes harvested from mice immunized 8 weeks post-PZQ treatment, completely restored the frequency of IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells to the levels seen in Igk-TD158 vaccinated naïve mice. The increase in frequency of IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells in PZQ treated mice was significantly higher than that of infected mice, with no significant difference between the frequency of IFN-γ producing CD8+ T cells in PZQ treated mice and naïve mice. These data show that PZQ treatment restores vaccine recipient ability to mount HIV-1C vaccine-specific T cell responses.

Fig. 5.

PZQ treatment restores the HIV-1C vaccine specific T cell immune response. Naïve mice (dotted bars), schistosome infected mice (solid bars), or PZQ treated mice (hatched bars) were vaccinated with Igκ-TD158 multi-epitope HIV-1C DNA vaccine. Naïve mice were vaccinated with pVAX plasmid as a negative control (open bars). Two weeks after the second injection, splenocytes from individual mice (minimum 8 mice/group) were harvested, plated at 300,000 and 150,000 cells/well and stimulated with P18 peptide (20 μM) or RPMI for 20 h. The frequencies of IFN-γ-producing CD8+ T cells (SFC) per million splenocytes in response to P18-I10, using both cell densities, were determined using IFN-γ ELISPOT assay (mean±SEM.). Schistosome infection significantly suppressed the HIV-1C specific T-cell immune responses (p<0.000001). The T cell immune responses to HIV-1C vaccine was partially but significantly restored when vaccination was initiated 4 weeks post PZQ treatment (A); and was completely restored when vaccination was started 8 weeks post PZQ treatment (B). At least two separate experiments with similar results were performed for each time point. * indicates statistically significant difference in the frequencies of CD8+ T cells between the infected and PZQ treated mice as determined by Student’s t-test (p<0.000001).

4. Discussion

Despite the advances and major strides on HIV-1 research, HIV remains a major public health problem world wide, especially in developing countries [4]. The development of an effective and safe vaccine for HIV is a key to the control of HIV-1 pandemic. There has been and remains an intensive effort to develop a protective vaccine for HIV-1. Development of HIV-1 vaccines has focused on vaccines that induce neutralizing antibodies to viral proteins [43–45], and vaccines that induce cellular immunity that target and kill HIV-infected cells [46–51]. A vaccine that induces both the production of neutralizing antibodies and cellular immunity would be ideal. Nonetheless, the majority of the HIV-1 candidate vaccines that are in clinical trials or about to enter clinical trials are T cell based, designed to elicit vaccine specific Th1 type and CTL immune responses [7–11,47,48,52–54].

A major concern for T cell based vaccines in developing country populations is the high prevalence of immune suppressive helminth infections in HIV endemic areas [12–16]. Helminth parasites strongly bias the host immune system towards Th2 type, induce T regulatory cells and immune suppression/anergy [17–30]. In this regard, we recently demonstrated that schistosome infection significantly suppressed HIV-1C vaccine-specific T cell responses in mice [37]. In agreement with this observation, several other studies have shown that helminth infections negatively impact vaccine-specific immune responses in humans [31–36,55].

Therefore, in the current study, we tested whether elimination of worms would restore the ability of the previously infected mice to mount strong HIV-1C vaccine-specific T cell responses. Elimination of helminth parasites by anthelminthic drugs is affordable and simple, and has a dual advantage: first, drug treatment reduces morbidity and mortality caused by infection with helminth parasites; and second, allows the development of appropriate immune responses to vaccines. Indeed, in this study, we found that elimination of schistosome infection with praziquantel treatment significantly restored the ability of mice to mount HIV-1C vaccine specific T cell immune responses. Immunization of mice with the Igκ-TD158 eight weeks post PZQ treatments resulted in complete restoration of P18-I10 specific T cell responses. Igκ-TD158 vaccine specific immune responses were consistently higher when vaccination was initiated 8 weeks post PZQ treatment as compared with mice vaccinated at 4 weeks post PZQ treatment, though these differences were not statistically significant. This could be due to the length of time needed to clear schistosome antigens, and/or for immune cells to cease producing Th2-type cytokines. For example, it is likely that the prolonged elevated IL-4 and IL-10 responses to SEA are due to the long period of time it takes to clear tissue-trapped developing parasite eggs and egg antigens post-PZQ treatment. Our results were consistent with the study by Cooper et al [33] which found that Ascaris lumbricoides infected patients had diminished Th1 response to cholera toxin B subunit (CT-B) vaccine. This same study also reported that albendazole treatment of Ascaris-infected individuals prior to vaccination with CT-B partially reversed the deficit in Th1 responses [33]. In a recent study, peripheral blood mononuclear cells from de-wormed (albendazole treatment) individuals were found to have higher frequencies of BCG vaccine specific IFN-γ and IL-12 producing cells than helminth infected individuals [36].

To examine the potential mechanism behind the negative impact of chronic helminth infection on the immunogenicity of HIV-1C vaccine T cell immune response, we measured cytokines produced by spleens obtained from naïve, schistosome infected or PZQ treated mice in response to schistosome antigens as well as to Concanavalin A. Schistosome infection induced increased production of IL-4 and IL-10 and decreased production of IFN-γ, as predicted from earlier studies examining Th2-bias in schistosome infection (for review see [19,21,56]). We found that PZQ treatment actually increased parasite specific IL-4 and IL-10 while in contrast, resulted in a significant decrease in IL-4 production in response to Con A stimulation. IFN-γ production was significantly increased in response to Con A as well as SEA stimulation in mice treated with PZQ. These data suggest that PZQ treatment corrected the overall immune balance in the host immune response based on cytokine responses to Con A, and pushed it towards Th1 type. Interestingly, IL-10 production from splenocytes from PZQ treated mice was increased in response to both SEA or Con A stimulation compared to infected and naïve mice. This is consistent with a recent study that showed that IL-10 mRNA expression was significantly increased in PZQ treated mice compared to infected mice [57]. Nonetheless, the role of IL-10 in the suppression of HIV-1C vaccine specific immune responses remains to be determined. In addition, we have not measured IL-10 production in response to the vaccine antigen, and therefore can not rule out the role of IL-10 in the suppression of vaccine specific T cell responses. A study by McElroy et al showed that individuals co-infected with S. mansoni and HIV-1 was associated with decreased CD8+ cytotoxic HIV-1 specific T cell responses coincident with increased numbers of HIV-1 specific IL-10 positive CD8+ T cells compared to individuals infected with HIV-1 alone [58]. Examining other potential immune suppressive cytokines, Elias et al [36] found that chronic helminth infection reduced the immunogenicity of BCG vaccine in humans and this was associated with increased TGF-β production in infected individuals. However, the study by Elias et al. [36] can not rule out the role of IL-10 in the immune suppression induced by helminth infection, since IL-10 was not measured. In our study, we have not measured TGF-β levels, and therefore, role of TGF-β in the suppression of HIV-1C vaccine specific immune responses remains to be determined.

Schistosomes and other helminth parasites are known for their ability to enhance the expansion of T regulatory cells [28–30]. We found that the absolute number of T regulatory cells (CD4+CD25+FoxP3+) was significantly increased in the spleens of schistosome infected mice compared to naïve mice; these numbers were significantly reduced after PZQ treatment (data not shown). The role of these regulatory T cells and the cytokines produced by them in the suppression of HIV-1C vaccine specific T cell responses remains to be determined. We are currently performing experiments to further investigate the mechanism of immune suppression induced by schistosome infection.

In conclusion, our study along with others, suggests that the modulation of host immune responses by helminth parasites has important implications for the design of T cell based vaccines against diseases such as HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis. Our data also suggest that elimination of helminth parasites using anthelminthic drugs could offer an affordable and a simple mean to enhance the immunogenicity of T cell based vaccines for HIV-1 and other infectious diseases. Nonetheless, large human clinical trials are still needed to evaluate the impact of helminth infections on T cell based vaccines, and to evaluate whether helminth elimination will restore the immunogenicity of T cell based vaccines.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Fred Lewis at the Biomedical Research Institute/NIH for providing us with the infected snails. We are also grateful to Drs. Jasmine McDonald, Khadija Iken, Smanla Tundup and Changlin Li for their technical assistant. This work was funded by the NIH grant number 1R01AI078787.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Barre-Sinoussi F, Chermann JC, Rey F, Nugeyre MT, Chamaret S, Gruest J, et al. Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) Science. 1983;220(4599):868–871. doi: 10.1126/science.6189183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallo RC, Salahuddin SZ, Popovic M, Shearer GM, Kaplan M, Haynes BF, et al. Frequent detection and isolation of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and at risk for AIDS. Science. 1984;224(4648):500–503. doi: 10.1126/science.6200936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popovic M, Sarngadharan MG, Read E, Gallo RC. Detection, isolation, and continuous production of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and pre-AIDS. Science. 1984;224(4648):497–500. doi: 10.1126/science.6200935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. [Accessed, June. 2009];Global AIDS Epidemic. 2008 Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/GlobalReport/2008/

- 5.Wainberg MA, Jeang KT. 25 years of HIV-1 research - progress and perspectives. BMC Med. 2008;6:31. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-6-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barouch DH. Challenges in the development of an HIV-1 vaccine. Nature. 2008;455(7213):613–619. doi: 10.1038/nature07352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duerr A, Wasserheit JN, Corey L. HIV vaccines: new frontiers in vaccine development. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(4):500–511. doi: 10.1086/505979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham BS. Clinical trials of HIV vaccines. Annu Rev Med. 2002;53:207–221. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ravanfar P, Mendoza N, Satyaprakash A, Jordan BI. HIV vaccines under study. Dermatol Ther. 2009;22(2):158–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2009.01228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spearman P, Kalams S, Elizaga M, Metch B, Chiu YL, Allen M, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a CTL multiepitope peptide vaccine for HIV with or without GM-CSF in a phase I trial. Vaccine. 2009;27(2):243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corey L, McElrath MJ, Kublin JG. Post-step modifications for research on HIV vaccines. Aids. 2009;23(1):3–8. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830e6d6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan MS. The global burden of intestinal nematode infections--fifty years on. Parasitol Today. 1997;13(11):438–443. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(97)01144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Silva NR, Brooker S, Hotez PJ, Montresor A, Engels D, Savioli L. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: updating the global picture. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19(12):547–551. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Utzinger J, Keiser J. Schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis: common drugs for treatment and control. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5(2):263–285. doi: 10.1517/14656566.5.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Werf MJ, de Vlas SJ, Brooker S, Looman CW, Nagelkerke NJ, Habbema JD, et al. Quantification of clinical morbidity associated with schistosome infection in sub-Saharan Africa. Acta Trop. 2003;86(2–3):125–139. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(03)00029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hotez PJ, Remme JH, Buss P, Alleyne G, Morel C, Breman JG. Combating tropical infectious diseases: report of the Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries Project. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(6):871–878. doi: 10.1086/382077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Araujo MI, de Jesus AR, Bacellar O, Sabin E, Pearce E, Carvalho EM. Evidence of a T helper type 2 activation in human schistosomiasis. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26(6):1399–1403. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grzych JM, Pearce E, Cheever A, Caulada ZA, Caspar P, Heiny S, et al. Egg deposition is the major stimulus for the production of Th2 cytokines in murine schistosomiasis mansoni. J Immunol. 1991;146(4):1322–1327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearce EJ, CMK, Sun J, JJT, McKee AS, Cervi L. Th2 response polarization during infection with the helminth parasite Schistosoma mansoni. Immunol Rev. 2004;201:117–126. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearce EJ, Caspar P, Grzych JM, Lewis FA, Sher A. Downregulation of Th1 cytokine production accompanies induction of Th2 responses by a parasitic helminth, Schistosoma mansoni. J Exp Med. 1991;173(1):159–166. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.1.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearce EJ, MacDonald AS. The immunobiology of schistosomiasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(7):499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sartono E, Kruize YC, Partono F, Kurniawan A, Maizels RM, Yazdanbakhsh M. Specific T cell unresponsiveness in human filariasis: diversity in underlying mechanisms. Parasite Immunol. 1995;17(11):587–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1995.tb01002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nutman TB, Kumaraswami V, Ottesen EA. Parasite-specific anergy in human filariasis. Insights after analysis of parasite antigen-driven lymphokine production. J Clin Invest. 1987;79(5):1516–1523. doi: 10.1172/JCI112982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Semnani RT, Law M, Kubofcik J, Nutman TB. Filaria-induced immune evasion: suppression by the infective stage of Brugia malayi at the earliest host-parasite interface. J Immunol. 2004;172(10):6229–6238. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hewitson JP, Grainger JR, Maizels RM. Helminth immunoregulation: the role of parasite secreted proteins in modulating host immunity. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2009;167(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borkow G, Bentwich Z. Chronic immune activation associated with chronic helminthic and human immunodeficiency virus infections: role of hyporesponsiveness and anergy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17(4):1012–1030. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.4.1012-1030.2004. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borkow G, Leng Q, Weisman Z, Stein M, Galai N, Kalinkovich A, et al. Chronic immune activation associated with intestinal helminth infections results in impaired signal transduction and anergy. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(8):1053–1060. doi: 10.1172/JCI10182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaccone P, Burton O, Miller N, Jones FM, Dunne DW, Cooke A. Schistosoma mansoni egg antigens induce Treg that participate in diabetes prevention in NOD mice. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(4):1098–1107. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor JJ, Mohrs M, Pearce EJ. Regulatory T cell responses develop in parallel to Th responses and control the magnitude and phenotype of the Th effector population. J Immunol. 2006;176(10):5839–5847. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.5839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKee AS, Pearce EJ. CD25+CD4+ cells contribute to Th2 polarization during helminth infection by suppressing Th1 response development. J Immunol. 2004;173(2):1224–1231. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Actor JK, Shirai M, Kullberg MC, Buller RM, Sher A, Berzofsky JA. Helminth infection results in decreased virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell and Th1 cytokine responses as well as delayed virus clearance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(3):948–952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabin EA, Araujo MI, Carvalho EM, Pearce EJ. Impairment of tetanus toxoid-specific Th1-like immune responses in humans infected with Schistosoma mansoni. J Infect Dis. 1996;173(1):269–272. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.1.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cooper PJ, Chico M, Sandoval C, Espinel I, Guevara A, Levine MM, et al. Human infection with Ascaris lumbricoides is associated with suppression of the interleukin-2 response to recombinant cholera toxin B subunit following vaccination with the live oral cholera vaccine CVD 103-HgR. Infect Immun. 2001;69 (3):1574–1580. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1574-1580.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper PJ, Espinel I, Wieseman M, Paredes W, Espinel M, Guderian RH, et al. Human onchocerciasis and tetanus vaccination: impact on the postvaccination antitetanus antibody response. Infect Immun. 1999;67(11):5951–5957. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5951-5957.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elias D, Akuffo H, Pawlowski A, Haile M, Schon T, Britton S. Schistosoma mansoni infection reduces the protective efficacy of BCG vaccination against virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Vaccine. 2005;23(11):1326–1334. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elias D, Britton S, Aseffa A, Engers H, Akuffo H. Poor immunogenicity of BCG in helminth infected population is associated with increased in vitro TGF-beta production. Vaccine. 2008;26(31):3897–3902. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.04.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Da’Dara AA, Lautsch N, Dudek T, Novitsky V, Lee TH, Essex M, et al. Helminth infection suppresses T-cell immune response to HIV-DNA-based vaccine in mice. Vaccine. 2006;24(24):5211–5219. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sartono E, Kruize YC, Kurniawan A, van der Meide PH, Partono F, Maizels RM, et al. Elevated cellular immune responses and interferon-gamma release after long-term diethylcarbamazine treatment of patients with human lymphatic filariasis. J Infect Dis. 1995;171(6):1683–1687. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takahashi H, Cohen J, Hosmalin A, Cease KB, Houghten R, Cornette JL, et al. An immunodominant epitope of the human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein gp160 recognized by class I major histocompatibility complex molecule-restricted murine cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(9):3105–3109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.9.3105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller MD, Yamamoto H, Hughes AL, Watkins DI, Letvin NL. Definition of an epitope and MHC class I molecule recognized by gag-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in SIVmac-infected rhesus monkeys. J Immunol. 1991;147(1):320–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Voss G, Letvin NL. Definition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 and gp41 cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitopes and their restricting major histocompatibility complex class I alleles in simian-human immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1996;70(10):7335–7340. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.7335-7340.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harn DA, Mitsuyama M, David JR. Schistosoma mansoni. Anti-egg monoclonal antibodies protect against cercarial challenge in vivo. J Exp Med. 1984;159(5):1371–1387. doi: 10.1084/jem.159.5.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haigwood NL, Stamatatos L. Role of neutralizing antibodies in HIV infection. Aids. 2003;17 (Suppl 4):S67–71. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200317004-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nabel GJ. Immunology. Close to the edge: neutralizing the HIV-1 envelope. Science. 2005;308(5730):1878–1879. doi: 10.1126/science.1114854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Montefiori DC. Neutralizing antibodies take a swipe at HIV in vivo. Nat Med. 2005;11(6):593–594. doi: 10.1038/nm0605-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barouch DH, Craiu A, Santra S, Egan MA, Schmitz JE, Kuroda MJ, et al. Elicitation of high-frequency cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses against both dominant and subdominant simian-human immunodeficiency virus epitopes by DNA vaccination of rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 2001;75(5):2462–2467. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.5.2462-2467.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Borrow P, Lewicki H, Hahn BH, Shaw GM, Oldstone MB. Virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity associated with control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1994;68(9):6103–6110. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6103-6110.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Novitsky V, Cao H, Rybak N, Gilbert P, McLane MF, Gaolekwe S, et al. Magnitude and frequency of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses: identification of immunodominant regions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C. J Virol. 2002;76(20):10155–10168. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10155-10168.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmitz JE, Kuroda MJ, Santra S, Sasseville VG, Simon MA, Lifton MA, et al. Control of viremia in simian immunodeficiency virus infection by CD8+ lymphocytes. Science. 1999;283(5403):857–860. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barouch DH, Craiu A, Kuroda MJ, Schmitz JE, Zheng XX, Santra S, et al. Augmentation of immune responses to HIV-1 and simian immunodeficiency virus DNA vaccines by IL-2/Ig plasmid administration in rhesus monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(8):4192–4197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050417697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shiver JW, Fu TM, Chen L, Casimiro DR, Davies ME, Evans RK, et al. Replication-incompetent adenoviral vaccine vector elicits effective anti-immunodeficiency-virus immunity. Nature. 2002;415(6869):331–335. doi: 10.1038/415331a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winstone N, Guimaraes-Walker A, Roberts J, Brown D, Loach V, Goonetilleke N, et al. Increased detection of proliferating, polyfunctional, HIV-1-specific T cells in DNA-modified vaccinia virus Ankara-vaccinated human volunteers by cultured IFN-gamma ELISPOT assay. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(4):975–985. doi: 10.1002/eji.200839167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peters BS, Jaoko W, Vardas E, Panayotakopoulos G, Fast P, Schmidt C, et al. Studies of a prophylactic HIV-1 vaccine candidate based on modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) with and without DNA priming: effects of dosage and route on safety and immunogenicity. Vaccine. 2007;25(11):2120–2127. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Letvin NL. Progress toward an HIV vaccine. Annu Rev Med. 2005;56:213–223. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.54.101601.152349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elias D, Wolday D, Akuffo H, Petros B, Bronner U, Britton S. Effect of deworming on human T cell responses to mycobacterial antigens in helminth-exposed individuals before and after bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccination. Clin Exp Immunol. 2001;123(2):219–225. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2001.01446.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thomas PG, Harn DA., Jr Immune biasing by helminth glycans. Cell Microbiol. 2004;6(1):13–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Helmy MM, Mahmoud SS, Fahmy ZH. Schistosoma mansoni: Effect of dietary zinc supplement on egg granuloma in Swiss mice treated with praziqantel. Exp Parasitol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McElroy MD, Elrefaei M, Jones N, Ssali F, Mugyenyi P, Barugahare B, et al. Coinfection with Schistosoma mansoni is associated with decreased HIV-specific cytolysis and increased IL-10 production. J Immunol. 2005;174(8):5119–5123. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.5119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]