Abstract

The use of binomial analysis as a tool for determining the sites of action of neuromodulators may be complicated by the nonuniformity of release probability. One of the potential sources for nonuniformity of release probability is the presence of multiple forms of synaptotagmins, the Ca2+ sensors responsible for triggering vesicular exocytosis. In this study we have used Sr2+, an ion whose actions may be restricted to a subpopulation of synaptotagmins, in an attempt to obtain meaningful estimates of the binomial parameters p (the probability of evoked acetylcholine [Ach] release) and n (the immediate available store of ACh quanta, whereby m = np). In contrast to results in Ca2+ solutions, binomial analysis of Sr2+-dependent release reveals a dramatically reduced dependence of n on extracellular Sr2+ concentrations. In Sr2+ solutions, blockade of potassium channels with 3,4-diaminopyridine increased m by an exclusive increase in p, whereas treatment with phorbol ester increased m solely by effects on n. The cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) analogue CPT-cAMP increased m by increasing both n and p. The effect of CPT-cAMP on p but not on n was blocked by protein kinase A (PKA) inhibitors, whereas the effect on n was mimicked by 8-CPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP, a selective agonist for exchange protein directly activated by cAMP, otherwise known as the cAMP-sensitive guanine nucleotide-exchange protein. The results demonstrate both the utility of the binomial distribution in Sr2+ solutions and the dual effects of cyclic AMP on both PKA-dependent and PKA-independent processes at the amphibian neuromuscular junction.

INTRODUCTION

Nerve-evoked neurotransmitter release is triggered by Ca2+ entry into the nerve terminal (Katz 1969); this occurs at specific loci where synaptic vesicles are primed to release their encapsulated neurotransmitter (Jahn and Sudhof 1999). It is generally thought that the synaptotagmins, a family of vesicle-associated proteins, represent the Ca2+-dependent triggers that couple Ca2+ entry to synaptic vesicle exocytosis (for review, see Chapman 2002). However, other candidates including the Ca2+ channels themselves have also been implicated as possible sensors for triggering vesicular exocytosis (Atlas et al. 2001; Cohen et al. 2005).

At the neuromuscular junction, fluctuations in the evoked release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh), reflected as endplate potential (EPP) amplitudes, can be fitted by the binomial distribution (Bennett et al. 1975; Miyamoto 1975; Searl and Silinsky 2002, 2003). Hence, the mean quantal content of EPPs m (the number of quanta released by a nerve impulse) is equal to the product of p (the average probability that vesicles will release their ACh contents) and n (the immediately available store of quanta or vesicles). One problem with binomial analysis of neurotransmitter release in Ca2+ solutions is that the binomial estimates of both p and n are dependent on extracellular Ca2+ concentrations, with p having a first-power relationship and n having a higher-power relationship (Bennett et al. 1975; Miyamoto 1975; Searl and Silinsky 2002, 2003). Many of the processes involved in vesicle mobilization and docking are likely to be Ca2+ dependent and, indeed, changes in intraterminal Ca2+ concentration have been demonstrated to be important for the recruitment of synaptic vesicles for release in the calyx of Held (Hosoi et al. 2007). However, changes in intraterminal Ca2+ resulting from altering extracellular Ca2+ concentrations may not be the only factor affecting the binomial estimate for n at the skeletal neuromuscular junction. One other possibility is that the anomalous Ca2+ dependence of the estimate of n is the result of variances in the individual release probabilities in Ca2+ solutions, biasing the binomial distribution (see METHODS and Redman 1990). Indeed, multiple forms of synaptotagmin with differing Ca2+ dependences for vesicle fusion have been reported (see, e.g., Chapman 2002; Xu et al. 2007) and, at the vertebrate neuromuscular junction, more than one synaptotagmin isoform contributes to evoked ACh release (Pang et al. 2006). Furthermore, multiple synaptotagmin isoforms have been shown to occur on different vesicle types (Wang et al. 2005) and to be colocalized on single synaptic vesicle populations (Osborne et al. 1999). The coexistence of multiple isoforms of synaptotagmin exhibiting different affinities for Ca2+ and thus different release probabilities might contribute to the anomalous Ca2+ dependence of n seen in the binomial modeling of neurotransmitter release. For example, changes in n might represent changes in release events with low affinities for Ca2+, whereas changes in p might reflect changes in release events with high affinity for Ca2+.

It might be useful to study evoked ACh release mediated by a more discrete set of synaptotagmins than those stimulated by Ca2+. Recent studies in artificial systems suggest that one way to restrict the number of synaptotagmin isoforms involved in vesicle exocytosis might be to substitute Sr2+ for Ca2+ (Bhalla et al. 2005; but see Shin et al. 2003). In Sr2+ solutions, the release process could then be confined to a pool of synaptotagmins with similar efficiencies for release, thus reducing the variance in p and resulting in independent estimates of p and n. Therefore binomial analysis of the Sr2+-evoked EPPs could provide independent estimates for n and p and thus allow us to identify more clearly the mechanisms by which neuromodulators affect the synaptic release process.

Herein, we show that Sr2+-evoked EPPs do conform to the binomial distribution and can be used to decipher the mode of action of important modulators of neurotransmitter release.

METHODS

General

Frogs (Rana pipiens) were killed by anesthesia with 5% ether, or 5% isoflurane followed by double pithing. This method is in accordance with guidelines laid down by our institutional animal welfare committee. In vitro cutaneous-pectoris nerve-muscle preparations were used in all experiments. Intracellular recordings were made using microelectrodes filled with 3 M KCl with resistances 3–10 MΩ. The signal from the microelectrode was fed into a conventional high-input impedance microelectrode preamplifier (Axoclamp-2A, Axon Instruments). Responses were fed into a personal computer using either a Digidata 1200 or TL1-125 A/D converter (Axon Instruments). Solutions were delivered by superfusion with a peristaltic pump and removed by vacuum suction. All experiments were carried out at room temperature (22–24°C).

Normal recording solutions contained (in mM): 115 NaCl, 12 KCl, 2 Hepes, and the indicated concentrations of CaCl2 or SrCl2. Miniature endplate potentials (MEPPs) and EPPs were analyzed using CDR, WCP, and SCAN programs (DOS versions, Strathclyde University Software; J. Dempster). The data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel, Corel Quattro Pro, and Sigma Plot. All drugs used in this study were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) or Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO).

Overview of binomial analysis of evoked neurotransmitter release

The simple binomial distribution is given by

| (1) |

In this equation, f(x) reflects the probability of observing 0, 1, 2, 3, . . . , n quanta released; p reflects the average probability of release; and q represents the probability of a failure of release [where q = (1 − p)]. As mentioned in the introduction

| (2) |

In the binomial distribution, the variance (var) is related to the average probability of release by the following equation

| (3) |

Briefly, the EPPs and MEPPs were collected with the EPPs corrected for nonlinear summation according to the method of McLachlan and Martin (1981). Binomial analysis of EPPs requires the use of a binomial model that incorporates the size and variance of the individual quantal amplitudes into the distribution (Miyamoto 1975). For derivations and estimates of errors, see Robinson (1976) and McLachlan (1978). The value of p was determined from the following equation

| (4) |

where EPP is the mean EPP amplitude, is the variance of EPP amplitudes, is the variance of MEPP amplitudes, and MEPP is the mean amplitude of the MEPPs (McLachlan 1978; Miyamoto 1975). Finally, n was determined by rearranging Eq. 2

| (5) |

where

| (6) |

Error estimates of m, n, and p were calculated using Eq. 18 in McLachlan (1978) and Eqs. 9 and 10 in Robinson (1976). MEPP amplitudes for analysis were obtained from spontaneous events occurring between the EPPs and fit a normal distribution (see Christian and Weinreich 1992; McLachlan 1978; Miyamoto 1975).

Sources of error in the binomial analysis of evoked neurotransmitter release

The simple binomial distribution may not give truly accurate estimates of n and p when evoked neurotransmitter release is studied (see McLachlan 1978). Three possible sources of error in the estimates of p derived by the simple binomial have been suggested: nonuniformity of p (spatial variance in p); nonstationarity of p (temporal variance of p); and nonstationarity of n (temporal variance of n). Given the presence of multiple forms of synaptotagmin, the most relevant source of error is likely to be the nonuniformity of p. This would bias the estimates of p because under such nonuniform conditions the estimate for p = the actual value of /the actual value of p (where is the variance of p; see Eq. 10 in Searl and Silinsky 2002). This error causes p to be weighted toward high-probability events (e.g., those exocytotic events linked to synaptotagmins with high affinities for Ca2+, thus overestimating p and underestimating the value of n; for discussion see Silinsky 1985). Under these conditions, raising the probability of the low-probability events will lead to an apparent increase in n. [For a more complete discussion of complex binomial distributions and the mathematical equations for the related errors see McLachlan (1978) and Searl and Silinsky (2002).] If the overall number of high release probability events is small relative to the population of low release probability events, then general changes in mean release probabilities will be accompanied by large changes in the binomial estimate for n. Thus the presence of multiple isoforms of synaptotagmins with markedly different Ca2+-coupling abilities might result in anomalous measures of n and p. In particular, effects that are mediated exclusively through changes in overall release probability will also produce changes in the binomial estimate for n, and the proportionate change in the binomial estimate for p will be underestimated. Previously, our binomial analysis of asynchronous release evoked by K+ depolarization in Sr2+ solutions allowed us to determine a lack of variance in p (Searl and Silinsky 2002). This provides further justification for applying binomial analysis to evoked release in Sr2+ solutions. In contrast to these results with Sr2+, in Ca2+ solutions the distribution of asynchronous release evoked by K+ depolarization did not allow us to rule out variance in p (Searl and Silinsky 2002).

Despite the apparent simplicity of the binomial distribution, exact interpretations of the binomial parameters n and p have proven to be elusive. At its simplest, n is a measure for the number of vesicles available for release and p is the release probability of those vesicles available for release. It has been tempting to equate n with morphological correlates such as the number of active zones with available vesicles and adequate calcium (reviewed in Silinsky 1985). Under some conditions (e.g., potassium channel blockade), the number of quanta released by a single stimulus is 1.5–2 orders of magnitude greater than the number of active zones (see discussion in Silinsky 1985). Indeed, despite recent advances in the molecular understanding of the vesicular release process, many questions remain such as whether all active zones are “active” and what mechanisms are involved in the activating of individual release sites (Logdon et al. 2006; Viele et al. 2003). In the initial phase of this study, we tested the effects of simple pharmacological manipulation of the two components of the release apparatus: i.e., probability of release (through increasing divalent cation entry) and number of vesicles available for release through the effects of phorbol ester. The results subsequently presented suggest that in Sr2+ solutions, binomial analysis of EPP amplitudes provides a measure of changes in the number of vesicles available for release and the probability of release of those synaptic vesicles.

Statistical comparisons

Full details are provided in Searl and Silinsky (2002). Comparisons were made by either parametric statistics (e.g., Student’s paired t-test) or nonparametric statistics (Mann–Whitney rank-sum test; see Glantz 1992). When more than two groups were compared, an ANOVA for the normally distributed data was followed by multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni inequality (see Glantz 1992). Data are presented as mean ± 1SE. Statistical significance was generally P < 0.05 except when otherwise noted.

RESULTS

General observations on dependence of m, n, and p on Sr2+ concentrations

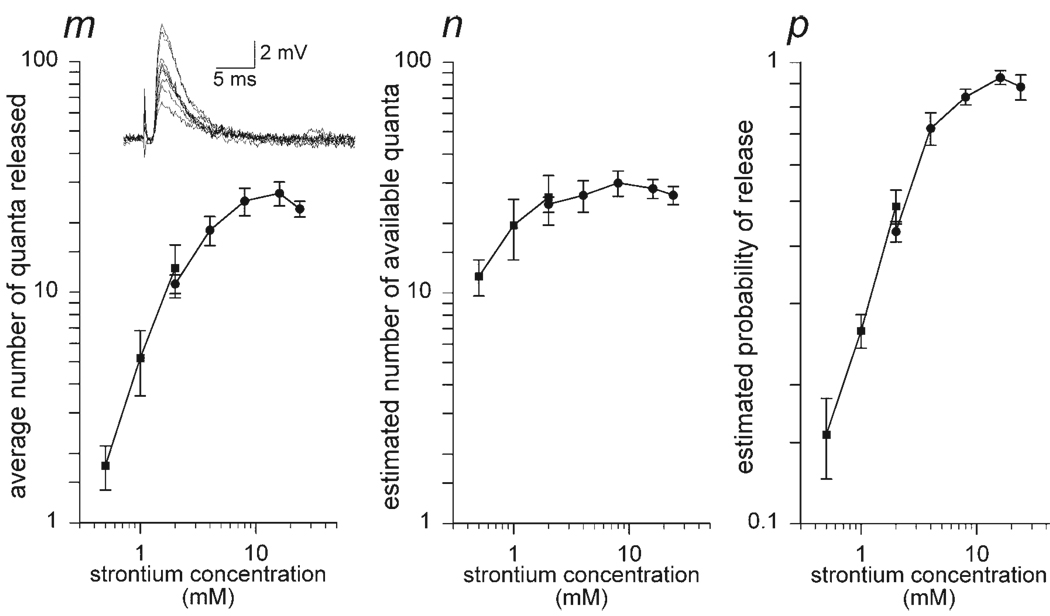

Nerve stimulation in 2 mM Sr2+ solutions produces fluctuating EPPs, which reflect the synchronous release of neurotransmitter quantified as m (see inset to Fig. 1). As previously found (Meiri and Rahamimoff 1971; Silinsky 1981), Sr2+ is less efficacious than Ca2+ in supporting EPPs. Specifically, the maximal values obtained for m in Sr2+ ranged from 25 to 39 quanta in contrast to the order-of-magnitude-higher m in Ca2+ (Meiri and Rahamimoff 1971; Silinsky 1981). Application of binomial analysis reveals that the change in m is largely a result of a change in p, with n showing little dependence on extracellular Sr2+ concentrations (Fig. 1). This contrasts with the results in Ca2+ solutions whereby binomial analysis reveals a steep Ca2+ dependence for n (see Bennett et al. 1975; Searl and Silinsky 2003). In all five experiments, there was no significant dependence of n on Sr2+ concentrations in the range between 1 and 24 mM (n = 5; ANOVA, P = 0.473 for concentrations 1–24 mM Sr2+; P = 0.741 for concentrations 2–24 mM Sr2+).

FIG. 1.

The concentration-dependent effects of Sr2+ on the binomial parameters of neurotransmitter release. Shown are the log–log plots of Sr2+ concentration and m, n, and p, respectively. Examples of nerve-evoked endplate potentials (EPPs, 0.2 Hz) obtained from a single endplate in 2 mM Sr2+ are shown in the inset. Unlike experiments in Ca2+ solutions, the changes in release (m) are principally mediated through changes in the probability of release. At concentrations ≥1 mM Sr2+ there was no significant increase in the parameter n and all changes in the quantal release m were due to changes in p (see text for statistical details). Because of the long time course of these experiments these data consist of 2 separate sets of experiments from single individual endplates; 0.5–2 mM Sr2+ (n = 5 experiments, indicated by the solid square symbols); 2–24 mM Sr2+ (n = 5 experiments, indicated by the solid round symbols). Each point shown represents the average ± SE of 5 experiments. It should be noted that at the low Sr2+ concentrations (i.e., between 0.5 and 1 mM Sr2+) there is an increase in the binomial estimate for both n and p. This might reflect either the presence of more than one isoform of Sr2+-sensitive synaptotagmin or, alternatively, might be due to variations in the entry of Sr2+ along the length of the nerve terminal.

As a corollary of the independence of n on extracellular Sr2+ concentrations, given that m = np, a much lower degree of apparent cooperativity is observed in the relationship between Sr2+ concentration and m when compared with Ca2+. As shown in Fig. 1, the log–log graphs of Sr2+ concentration against m exhibit relationships dramatically different from those of Ca2+ (for comparison see Searl and Silinsky 2003). Specifically, Hill plots of Sr2+ concentration and release (m) have an initial slope close to 2, becoming close to 1 at a concentration > 2 mM Sr (i.e., at concentrations in which n is independent of Sr2+ concentrations). In Ca2+, Hill plots of release have initial slopes close to 4 (see Bennett et al. 1975; Searl and Silinsky 2003). These results are all consistent with the suggestion that the effects of Sr2+ may be confined to a more restricted pool of synaptotagmins than Ca2+.

Independent modulation of the binomial parameter p in Sr2+ solutions

Deviations from a simple binomial distribution may not be detectable using statistical methods (see, e.g., Brown et al. 1976). However, it should be possible to test for anomalies in the binomial model by the application of experimental manipulations. One such test would be the effect of changes in neurotransmitter release probability on the binomial estimates for release. To our knowledge, there is no agent known to unequivocally change vesicle release probability at motor nerve endings or ganglionic synapses (for review see McLachlan 1978). However, the generally accepted model—that Ca2+ triggers vesicle release—would suggest that agents that increase Ca2+ entry (without changing the ionic composition of the bathing fluid) should produce increases in the binomial estimate for p.

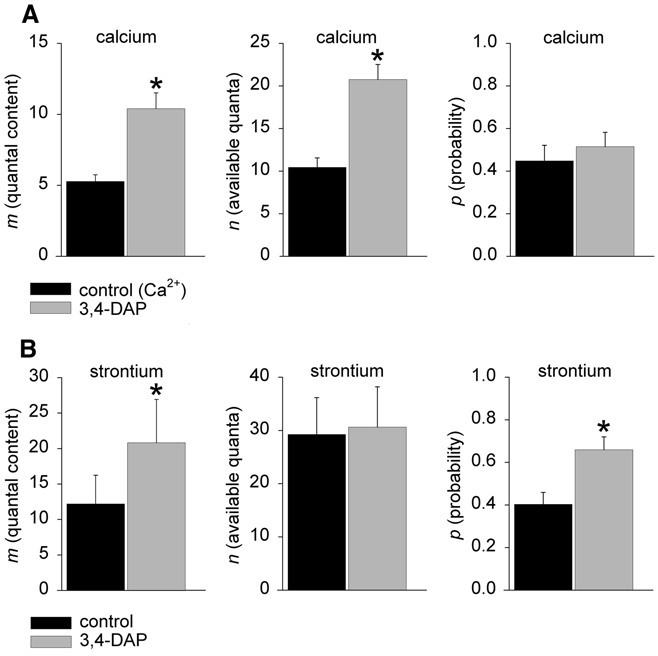

For these experiments, we used the potassium channel blocker 3,4-diaminopyridine (3,4-DAP), which increases neurotransmitter release by prolonging nerve terminal depolarization and thus divalent earth ion entry (Durant and Marshall 1980; Molgo et al. 1977). We compared the effects of 3,4-DAP on neurotransmitter release in Ca2+ and Sr2+ solutions (Fig. 2). For the Ca2+ experiments, we chose a concentration of 0.2 mM Ca2+ because binomial analysis at this concentration of Ca2+ gives a value of p close to 0.5 (Searl and Silinsky 2003). Prolongation of nerve-terminal depolarization may lead to recruitment of additional synaptic vesicles (Heuser et al. 1979; Katz and Miledi 1979). We therefore used a moderate concentration of 3,4-DAP for these experiments, sufficient to approximately double the level of release. As shown in Fig. 2A, the increase in m caused by a 10-min incubation with 10 µM 3,4-DAP in 0.2 mM Ca2+ solutions was due entirely to the apparently anomalous effect of an increase in the parameter n, with no measurable effect on the parameter p. Specifically, the value for m increased from 5.29 ± 0.46 in control to 10.43 ± 1.11 after 3,4-DAP (P < 0.005), the value for n increased from 13.4 ± 2.1 in control to 20.7 ± 1.8 after 3,4-DAP (P < 0.05), and the value for p was unchanged (0.45 ± 0.07 in control and 0.51 ± 0.07 after 3,4-DAP, n = 6 experiments from single endplates, separate preparations). This confirms the previous finding of Lundh (1979) using the related agent 4-aminopyridine.

FIG. 2.

The effect of the K+ channel blocker 3,4-diaminopyridine (3,4-DAP) on the binomial parameters of release in Ca2+ and Sr2+ solutions. As shown in A, in 0.2 mM Ca2+ binomial analysis of the increase in release m produced by a 10-min incubation with 10 µM 3,4-DAP results in an increase in the apparent value of n with no change in the estimate for p (asterisks indicate significance, P < 0.05; see main text for specific details). Note: Supplemental Fig. S1, A and B shows the effect of 3,4-DAP on the amplitude distribution of EPPs recorded in Ca2+. B: the effect of 3,4-DAP on the binomial parameters of release in Sr2+ solutions. In contrast to the results with Ca2+ (A), the increase in m produced by a 10-min incubation with 10 µM 3,4-DAP in 2 mM Sr2+ was not associated with a change in the estimate for n. Rather, the increase in m produced by 3,4-DAP is mediated entirely through an increase in p (asterisks indicate significance, P < 0.05; see text for further details). Note: Supplemental Fig. S1, C and D shows the effect of 3,4-DAP on the amplitude distribution of EPPs recorded in Sr2+.

We then performed similar experiments in Sr2+ solutions. In these experiments we used a concentration of 2 mM Sr2+ as our test solution because this concentration produces an estimate for p close to 0.5 (see Fig. 1) and thus should be optimal, both for recording changes in p and for the accuracy of these binomial estimates. In contrast to the results in Ca2+ solutions, the increase in release m produced by a 10-min incubation with 10 µM 3,4-DAP in Sr2+ solutions was exclusively due to an increase in the probability of ACh release p (Fig. 2B). Specifically, the value for m increased from 12.19 ± 4.03 in control to 20.81 ± 6.11 after 3,4-DAP (P < 0.05); the value for n was unchanged (29.3 ± 6.9 in control, 30.6 ± 6.1 after 3,4-DAP), and the value for p was increased from 0.40 ± 0.06 in control to 0.66 ± 0.06 after 3,4-DAP (P = 0.006, n = 5 experiments from single endplates, separate preparations). For further illustration of the effects of DAP on EPP amplitude distributions in Ca2+ and Sr2+ solutions, we refer the reader to Supplemental Fig. S1,1 which shows examples of the fits produced by the binomial estimates obtained in these experiments.

The results presented thus far demonstrate that selective changes in p can be observed in Sr2+ solutions under conditions that alter the entry of alkaline earth cations into the nerve ending.

Independent modulation of the binomial parameter n in Sr2+ solutions

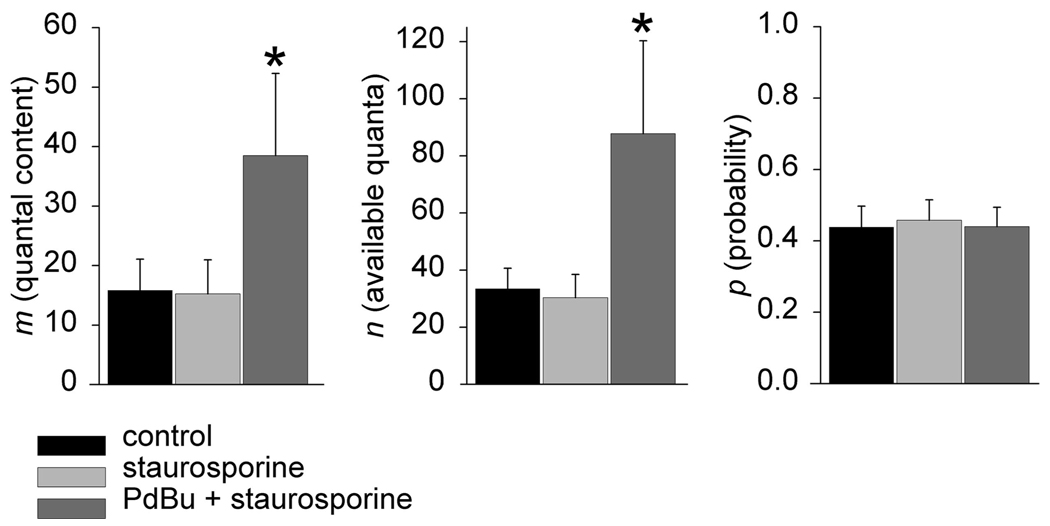

As a further test of this methodology, we decided to examine whether the binomial parameter n can be modulated independently of the probability of release in Sr2+ solutions. As before we used 2 mM Sr2+ solutions and we chose a signal transduction pathway that we previously found to affect the size of the readily releasable store as determined by rapid bursts of stimuli in high-Ca2+ solutions (Searl and Silinsky 2003). This pathway is responsible for the priming of the secretory apparatus by the phorbol ester/diacylclycerol receptor Munc-13. These experiments were carried out in the presence of staurosporine (1 µM) to confine the effects of phorbol dibutyrate (PDBu) to those on secretory events unrelated to protein kinase C (Tamaoki et al. 1986). Under these conditions it should be expected that increases in neurotransmitter release by PDBu result exclusively from its binding to the C1 domain on Munc-13 (Betz et al. 2001; Redman et al. 1997; Searl and Silinsky 1998, 2003). The activated Munc-13 then acts in consort with core protein syntaxin to promote vesicle priming at the amphibian neuromuscular junction (Betz et al. 2001; Searl and Silinsky 1998, 2003). Thus the increases in m produced by PDBu should result from an increase in the number of primed vesicles (i.e., the binomial parameter n) with no effect on the binomial parameter p. As shown in Fig. 3, this is indeed the case. Application of staurosporine had no effect either on the release of neurotransmitter or on the binomial estimates for n and p. The addition of PDBu caused an increase in m, the number of vesicles released (P < 0.05), with no effect on the binomial estimate for p. Specifically m = 15.8 ± 5.3 quanta, n = 33.4 ± 7.2 quanta, and P = 0.44 ± 0.06 in the control condition. In staurosporine, m = 15.2 ± 5.7 quanta, n = 30.3 ± 8.2 quanta, and P = 0.46 ± 0.06. Following the addition of 100 nM PDBu in staurosporine, m = 38.5 ± 13.8, n = 87.7 ± 32.5 quanta, and P = 0.44 ± 0.05 (n = 6 experiments from single endplates, separate preparations).

FIG. 3.

The effect of the phorbol ester phorbol dibutyrate (PDBu) on the binomial parameters of release in Sr2+ solutions. Staurosporine (1 µM) had no effect on EPP amplitudes or on the binomial parameters of release compared with control. Application of PDBu resulted in a significant increase in m that was exclusively through an effect on n (n = 6 experiments; asterisks indicate significance, P < 0.05). See text for more details.

The results thus far suggest that Sr2+ is a useful tool for the study of the parameters p and n at motor nerve endings and should help distinguish between potential sites of neurotransmitter release modulation. We thus applied these results to investigating the effects of cAMP on evoked ACh release.

Dual effects of cyclic AMP on the ACh release parameters n and p in Sr2+ solutions

Cyclic AMP is an important positive modulator of the release of neurotransmitter substances at many synapses (Brunelli et al. 1976; Seino and Shibasaki 2005) including ACh release at the amphibian neuromuscular junction (Hirsh et al. 1990). Recently it has become clear that effects of cAMP are mediated by both PKA-dependent and PKA-independent processes (Cheung et al. 2006; Ozaki et al. 2000).We used the membranepermeant adenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cAMP) analog 8-(4-chlorophenylthio) (CPT) for our initial studies. CPT-cAMP does not distinguish between the PKA-dependent and PKA-independent effects of cAMP (Dao et al. 2006).

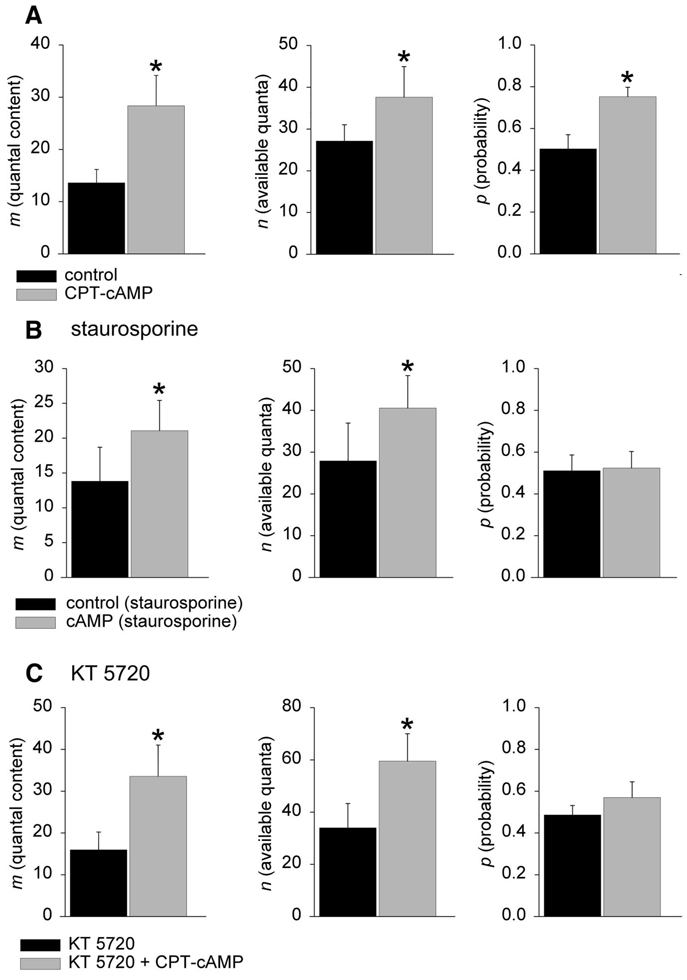

As shown in Fig. 4A, CPT-cAMP (1 mM) increases quantal release m by an effect on both binomial parameters n and p. Specifically, application of CPT-cAMP resulted in an increase in the number of quanta released m from 13.6 ± 2.6 in control to 28.3 ± 5.9 in CPT-cAMP (P < 0.05). The number of quanta available for release n was increased from 27.1 ± 3.8 in control to 37.6 + 7.4 in CPT-cAMP (P < 0.05) and p was increased from 0.50 ± 0.07 to 0.75 ± 0.05 (P < 0.001; n = 6 experiments from single endplates, separate preparations). To determine whether one or both of these effects are mediated via PKA, we repeated the experiments of Fig. 4A in the presence of either the nonselective protein kinase inhibitor staurosporine (1 µM) (Fig. 4B) or the selective PKA inhibitor KT 5720 (3 µM; C32H31N3O5, CAS #108068-98-0) (Kase et al. 1987; see Fig. 4C). In the presence of either inhibitor, the increase in release produced by CPT-cAMP was exclusively due to an increase the size of the immediately available store of ACh quanta n. Specifically, in the presence of staurosporine (Fig. 4B), application of CPT-cAMP resulted in an increase in the number of quanta released m from 13.8 ± 4.9 quanta in staurosporine alone to 21.0 ± 4.3 quanta in CPT-cAMP (P < 0.05). The number of quanta available for release n was increased from 27.9 ± 9.1 in control to 40.5 ± 7.8 in CPT-cAMP (P < 0.05). The probability of release was unchanged (0.50 ± 0.06 in control, 0.51 ± 0.08 in CPT-cAMP; n = 5 experiments from single endplates, separate preparations). In the presence of KT 5720 (Fig. 4C), m was increased from 16.0 ± 4.3 quanta in KT 5720 alone to 33.5 ± 7.5 quanta in CPT-cAMP + KT 5720 (P < 0.05). As with the experiments with staurosporine, this increase in neurotransmitter release was mediated through increases in n alone. Specifically, the number of quanta available for release n was increased from 34.0 ± 9.1 in control to 59.5 ± 10.5 in CPT-cAMP (P < 0.01). The probability of release was unchanged (0.49 ± 0.04 in control, 0.56 ± 0.06, in CPT-cAMP; n = 4 experiments from single endplates, separate preparations). Thus in the presence of PKA antagonists the effect of CPT-cAMP on the binomial parameter p was abolished, but the effect of CPT-cAMP on n was unaffected. These data suggest that two separate components of the release process are affected by CPT-cAMP: one that is blocked by PKA antagonists and the other that is PKA independent. The results of these experiments with PKA antagonists suggest that the PKA-dependent effects of cAMP on neurotransmitter release are exerted on the binomial parameter p and that PKA-independent effects are mediated by increases in n.

FIG. 4.

The effect of 8-(4-chlorophenylthio) (CPT), a membrane-permeable analog of adenosine-3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (cAMP), on the binomial parameters of release in Sr2+ solutions. CPT-cAMP activates PKA and other cAMP-dependent processes. In A, application of CPT-cAMP resulted in an increase in the number of quanta released m, mediated through increases in both the binomial estimates for n and p. See text for further details. Note: other studies (Huang and Hsu 2006; Zhong and Zucker 2005) used the adenylyl cyclase activator forskolin. However, in Sr2+ solutions the effects of forskolin were unreliable (despite having a nearly 3-fold increase in transmitter release in Ca2+ solutions), possibly because of calcium dependences in the activity of adenylyl cyclase. B and C show the effects of protein kinase A (PKA) inhibitors on the effect of CPT-cAMP. As shown in B, in the presence of staurosporine (1 µM), application of CPT-cAMP resulted in an increase in the number of quanta released m, an effect that was mediated through increases in n alone. C shows the effect of the selective PKA inhibitor KT 5720 (3 µM) on the increase in neurotransmitter release mediated by CPT-cAMP. As shown, in the presence of KT 5720 (3 µM), application of CPT-cAMP resulted in an increase in the number of quanta released that was due exclusively to an increase in n (asterisks indicate significance, P < 0.05). See text for further details.

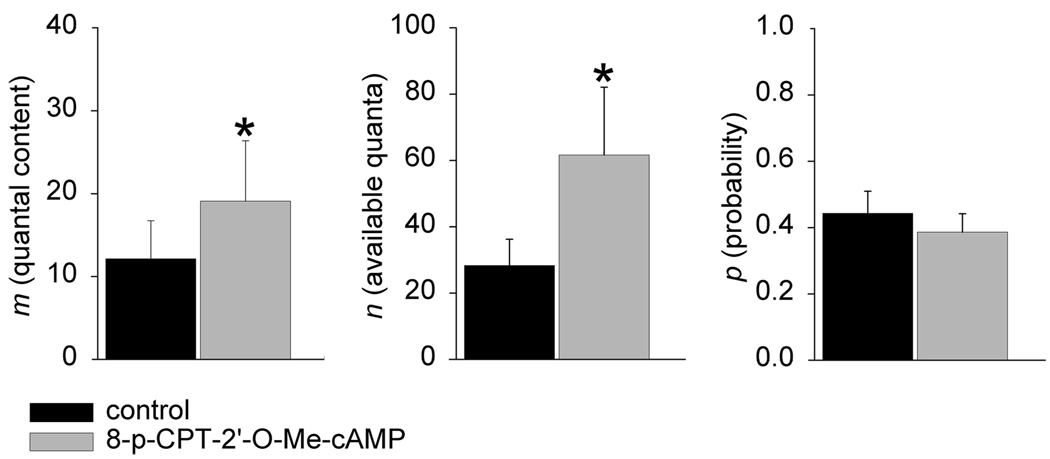

Is the PKA-independent effect of cAMP mediated by Epac?

Epac (exchange protein directly activated by cAMP) has recently been implicated in mediating increases in neurotransmitter release at crayfish (Zhong and Zucker 2005) and Drosophila (Cheung et al. 2006) neuromuscular junctions. We therefore decided to test whether the non-PKA-dependent effects of CPT-cAMP on release could be explained by the actions of CPT-cAMP on Epac or another cAMP-dependent system using the selective Epac agonist 8CPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (500 µM) (Christensen et al. 2003; Kang et al. 2003). As shown in Fig. 5, 8CPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP produces an increase in m exclusively by increasing n. Specifically, m was increased from 12.6 ± 4.1 quanta in control to 21.5 ± 6.2 quanta in 8CPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (P < 0.05) and the number of quanta available for release n was increased from 28.3 ± 7.9 in control to 61.7 ± 20.4 in 8CPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (P < 0.05). The estimated value of p was unchanged (0.44 ± 0.07 in control, 0.39 ± 0.06, in 8CPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP; n = 6 experiments). This result is thus consistent with the suggestion that the PKA- independent effects of CPT-cAMP on neurotransmitter release at the frog neuromuscular junction are mediated by Epac and due exclusively to changes in n.

FIG. 5.

The effect of the selective Epac (exchange protein directly activated by cAMP) activator 8CPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP on neurotransmitter release. Application of 8CPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP (500 µM) resulted in an increase in m that was mediated through increases in n alone (asterisks indicate significance, P < 0.05). For further details, see text.

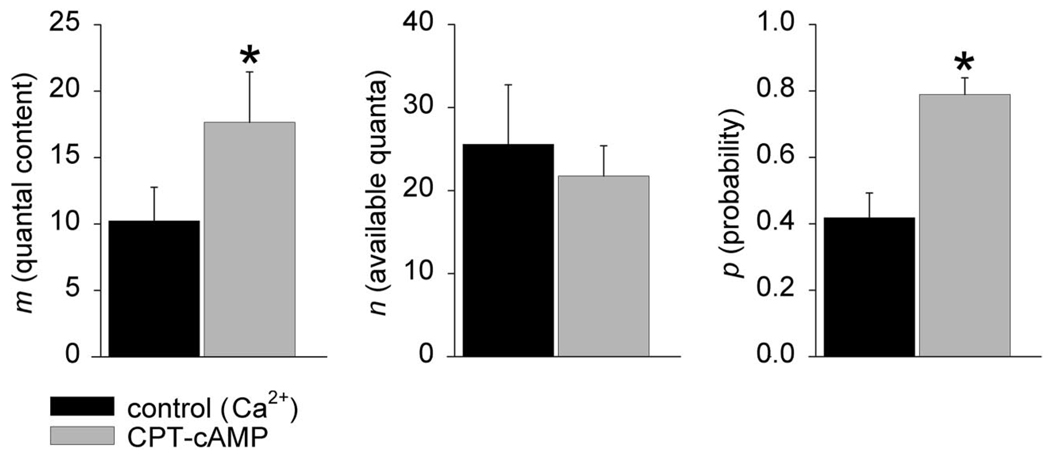

Is the effect of cAMP on release probability confined to an effect on high-probability release?

It has previously been reported that cAMP selectively increases the release probability of high release probability vesicles in medial prefrontal cortex neurons and at the calyx of Held (Huang and Hsu 2006; Kaneko and Takahashi 2004; Sakaba and Neher 2001). These vesicles might be equivalent to the high-probability (and thus high Ca2+ affinity) quantal release that we observed in low-Ca2+ calcium solutions (see, e.g., Fig. 2A). If so then the selective increases in the release probability of high release probability synaptic vesicles might occur if the effects of PKA are directed at those isoforms of synaptotagmin that have higher calcium affinity. We tested for this possibility by applying CPT-cAMP in 0.2 mM Ca2+ solutions. Under these conditions, high-Ca2+-affinity isoforms of synaptotagmin (and thus high-probability release events) are likely to be responsible for the majority of release. If the increase in release probability were universally applied toward all synaptotagmin isoforms then an increase in n would be expected in Ca2+ solutions, as is the case in Fig. 2A. However, if the effects of PKA activation on release probability were confined to high-probability release events, then an increase in p would be expected. As shown in Fig. 6, application of CPT-cAMP (1 mM) in low (0.2 mM) calcium resulted in an increase in quantal release through an effect that was exclusively through an increase in the binomial estimate for p. This suggests that the high-probability (low-Ca2+-threshold) release sites seen in calcium solutions and those events activated by Sr2+ are the same—a suggestion in accord with the known fusion efficiencies of Ca2+and Sr2+ in artificial membrane systems containing synaptotagmin IX (Bhalla et al. 2005).

FIG. 6.

The effect of CPT-cAMP on the binomial parameters of release in low-Ca2+ (0.2 mM) solutions. Application of CPT-cAMP resulted in an increase in the number of quanta released m. This increase in neurotransmitter release was mediated through increases in p alone (asterisks indicate significance, P < 0.05). It might seem surprising that, unlike the Sr2+ experiments, CPT-cAMP had no effect on the binomial parameter n in these Ca2+ solutions. However, under conditions when there is a discontinuous distribution of p, increases in release probability that are exclusively directed to the high-probability events, binomial analysis could result in an apparent reduction in n as well as an increase in p. Thus increases in the number of vesicles available for release may be masked by the selective increase in probability of high-probability release sites.

DISCUSSION

Utility of binomial analysis in Sr2+ solutions

The magnitude of evoked neurotransmitter release (m) can be modulated by changes in the number of synaptic vesicles available for release (n) or through changes in the release probability of those available vesicles (p). Current models for the release process suggest that neurotransmitter release is triggered by Ca2+ binding to the Ca2+ sensor synaptotagmin. As a result, release probability p should be dependent on Ca2+ entry and the efficiency by which Ca2+ couples to synaptotagmin and the exocytotic event, whereas n (the number of vesicles available for release) should be governed by the processes involved in the priming and docking of synaptic vesicles. Thus binomial analysis should provide useful information as to whether release is modulated through effects on the number of synaptic vesicles available for release or through changes in the release probability of those synaptic vesicles.

By using Sr2+ to evoke synchronous neurotransmitter release, we have isolated a component of evoked neurotransmitter release that conforms to the binomial distribution without the concentration dependence of n seen in Ca2+ solutions. Currently, there are two competing models, both of which might explain the differences between Ca2+ and Sr2+ on the release process. One possibility is that only a fraction of the total available pool of synaptotagmins is responsible for release in Sr2+ solutions (Bhalla et al. 2005). Alternately, it might be that fewer Ca2+ binding sites on the individual synaptotagmins are involved in Sr2+-triggered release (Shin et al. 2003). Either possibility would explain both the reduced cooperativity of the release process and the improved utility of the binomial analysis for Sr2+-dependent ACh release when compared with evoked release in Ca2+ solutions because either effect might be predicted to reduce the variance in release sensitivity for individual vesicles.

Although statistical tests (including χ2 tests) cannot distinguish between complex and simple binomials (see Bennett et al. 1975), the binomial model can be tested experimentally through modifications that would be expected to change p, the probability of release. As we show here, modifications that increase Sr2+ entry into the nerve endings, either by increasing extracellular Sr2+ (Fig. 1) or by using the K+ channel blocker 3,4-DAP (Fig. 2B), produced increases in p without effect on the binomial parameter n. The selective effects of phorbol esters on the parameter n in Sr2+ solutions (Fig. 3) confirm our previous findings in Ca2+ solutions (Searl and Silinsky 2003) and add to the validity of our approach using Sr2+.

From what is currently known about the functional divalent cation selectivity and sensitivity of synaptotagmin isoforms involved in synaptic transmission, it is likely that the component of release evoked by Sr2+ represents those release events that have a high-Ca2+ sensitivity. Given a restricted pool of synaptotagmins that can be stimulated by Sr2+, the question arises as to whether all vesicles can be released in Sr2+ solutions. In chromaffin cells, Fukuda and colleagues (2002) concluded that synaptotagmin IX and I were likely to be colocalized on dense core vesicles in chromaffin cells. More directly, experiments using FM-143 in goldfish bipolar neurons (Neves et al. 2001) demonstrated that all synaptic vesicles were releasable by Sr2+, albeit at a slower rate. Interestingly, these authors concluded that the slower rate of release of vesicles evoked by Sr2+ was attributable to a lower number of primed vesicles in the rapidly releasable store. Thus the value for n in our experiments might be related to a smaller size of the readily releasable store of vesicles in Sr2+ solutions. It is not clear, however, whether a similar use of binomial analysis of evoked neurotransmitter release in Sr2+ solutions will be generally applicable to other synapses, where the probability of a vesicle being available for release may be the major determinant of p (i.e., n may not be a constant).

Binomial analysis of the effects of cAMP analogs

Using the binomial distribution to analyze the effects of cAMP on ACh release in Sr2+ solutions, we find that cAMP increases neurotransmitter release by effects on both p and n (Fig. 4A). The cAMP-dependent increase in p is mediated through PKA dependence, whereas the increase in n is insensitive to protein kinase inhibition (Fig. 4, B and C). Our results are in accord with previous studies at the calyx of Held using both forskolin and cAMP (Kaneko and Takahashi 2004; Sakaba and Neher 2001). The effect of cAMP on n, the number of vesicles available for release was mimicked by the Epac agonist 8CPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP. One possible target for the effects of this Epac agonist on ACh release is RIM (Rab-interacting molecule; Koushika et al. 2001), which is a presynaptic membrane protein localized to the active zone of nerve endings (Dulubova et al. 2005). In addition to interacting with Epac (Ozaki et al. 2000), RIM also interacts with the SNARE syntaxin and the N-terminal domain of Munc13-1; in C. elegans RIM has been implicated in vesicle priming (Koushika et al. 2001). Thus the increase in n resulting from the effects of CPT-cAMP and 8CPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP seen in these experiments could be due to downstream effects of Epac regulating the conformational folding of syntaxin. However, other mechanisms may also exist. For example, p42/p44 MAP kinase has been implicated in the non-PKA effects of cAMP on neurotransmitter release (Huang and Hsu 2006).

The mechanism by which PKA increases p may be more readily interpreted. Changes in p are likely to be restricted to perturbations that either change Ca2+ entry (i.e., through effects on either Ca2+ or K+ channels) or change the affinity of synaptotagmin for Ca2+ (or the distance of synaptotagmin from the Ca2+ channel). In this regard PKA activation has been found to increase release probability independently of cation entry in both hippocampal (Trudeau et al. 1996) and cerebellar (Chavis et al. 1998; Chen and Regehr 1997) synapses. Our binomial analysis of the effects of CPT-cAMP on neurotransmitter release in low-Ca2+ solutions is in support of these results. Specifically, we found an increase in p, with no measurable effect on n in low-Ca2+ solutions (Fig. 6). This result rules out a generalized increase in Ca2+ entry because the mechanism by which cAMP increases p as a generalized increase in release probability would result in an increase in n in calcium solutions (see, e.g., Fig. 2). Our results are thus consistent with a selective increase in the release probability of a population of high-probability release events. Finally, direct recording of Na+, K+, and Ca2+ perineural waveforms revealed no effects of CPT-cAMP on the currents (data not shown), suggesting that the effects of CPT-cAMP are mediated downstream of nerve terminal channel activity.

There are many potential targets in nerve endings for the effects of protein kinase A, including cysteine string proteins, snapin, SNAP-25 (for a comprehensive review see Seino and Shibasaki 2005). However, agents that target these proteins are more likely to cause increases in the numbers of vesicles available for release rather than increases in p. Although synaptotagmin I has been mapped for phosphorylation sites, it does not have a PKA phosphorylation site (Pyle et al. 2000). More recently a PKA phosphorylation site located on synaptotagmin 12 has been identified (Maximov et al. 2007). It is thus possible that the form of synaptotagmin activated by Sr2+ is selectively phosphorylated by PKA, leading to an increase in the affinity of Ca2+ or Sr2+ for release. Alternatively, it might be that PKA phosphorylates a particular component of the release machinery that provides for a selective modulation of the synaptotagmin stimulated by Sr2+.

General conclusions

In conclusion, the application of the binomial distribution to the release of neurotransmitter in Sr2+ solutions at the frog neuromuscular junction provides an accurate method for determining the mechanism of modulation of neurotransmitter release. In particular this technique, which we have validated by a number of experimental tests, provides clear evidence for the separate actions of PKA-dependent and PKA-independent effects of cAMP on the release process. Furthermore, these results point to a selective modulation by PKA of release events of high-Ca2+ affinity (low-threshold events). Such modulation by PKA may play a role in synapses where forms of synaptotagmin with high-Ca2+ affinity predominate or where the influx of divalent cations in response to nerve activity is low due to a paucity of Ca2+ channels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

GRANTS

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service/National Institutes of Health Grants NS-12782 and AA-016513.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental data.

REFERENCES

- Atlas D, Wiser O, Trus M. The voltage-gated Ca2+ channel is the Ca2+ sensor of fast neurotransmitter release. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2001;21:717–731. doi: 10.1023/A:1015104105262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MR, Florin T, Hall R. The effect of calcium ions on the binomial statistic parameters which control acetylcholine release at synapses in striated muscle. J Physiol. 1975;247:429–446. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp010939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz A, Thakur P, Junge HJ, Ashery U, Rhee JS, Scheuss V, Rosenmund C, Rettig J, Brose N. Functional interaction of the active zone protein Munc13-1 and RIM1 in synaptic vesicle priming. Neuron. 2001;30:183–196. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla A, Tucker WC, Chapman ER. Synaptotagmin isoforms couple distinct ranges of Ca2+, Ba2+, and Sr2+ concentration to SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4755–4764. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TH, Perkel DH, Feldman MW. Evoked neurotransmitter release: statistical effects of nonuniformity and nonstationarity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:2913–2917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.8.2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunelli M, Castellucci V, Kandel ER. Synaptic facilitation and behavioral sensitization in Aplysia: possible role of serotonin and cyclic AMP. Science. 1976;194:1178–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.186870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman ER. Synaptotagmin: a Ca2+ sensor that triggers exocytosis? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:498–508. doi: 10.1038/nrm855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavis P, Mollard P, Bockaert J, Manzoni O. Visualization of cyclic AMP-regulated presynaptic activity at cerebellar granule cells. Neuron. 1998;20:773–781. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Regehr WG. The mechanism of cAMP-mediated enhancement at a cerebellar synapse. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8687–8694. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-22-08687.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung U, Atwood HL, Zucker RS. Presynaptic effectors contributing to cAMP-induced synaptic potentiation in Drosophila. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:273–280. doi: 10.1002/neu.20218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen AE, Selheim F, de Rooij J, Dremier S, Schwede F, Dao KK, Martinez A, Maenhaut C, Bos JL, Genieser HG, Doskeland SO. cAMP analog mapping of Epac1 and cAMP-kinase. Discriminating analogs demonstrate that Epac and cAMP-kinase act synergistically to promote PC-12 cell neurite extension. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:35394–35402. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian EP, Weinreich D. Presynaptic histamine H1 and H3 receptors modulate sympathetic ganglionic synaptic transmission in the guinea-pig. J Physiol. 1992;45:407–430. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen R, Schmitt BM, Atlas D. Molecular identification and reconstitution of depolarization-induced exocytosis monitored by membrane capacitance. Biophys J. 2005;89:4364–4373. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.064642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dao KK, Teigen K, Kopperud R, Hodneland E, Schwede F, Christensen AE, Martinez A, Døskeland SO. Epac1 and cAMP-dependent protein kinase holoenzyme have similar cAMP affinity, but their cAMP domains have distinct structural features and cyclic nucleotide recognition. J Biol Chem. 2001;281:21500–21511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603116200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulubova I, Lou X, Lu J, Huryeva I, Alam A, Schneggenburger R, Sudhof TC, Rizo J. A Munc13/RIM/Rab3 tripartite complex: from priming to plasticity? EMBO J. 2005;24:2839–2850. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant NN, Marshall IG. The effects of 3,4-diaminopyridine on acetylcholine release at the frog neuromuscular junction. Eur J Pharmacol. 1980;67:201–208. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(80)90499-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda M, Kowalchyk JA, Zhang X, Martin TF, Mikoshiba K. Synaptotagmin IX regulates Ca2+-dependent secretion in PC12 cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:4601–4604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100588200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantz SA. Primer of Biostatistics. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Heuser JE, Reese TS, Dennis MJ, Jan Y, Jan L, Evans L. Synaptic vesicle exocytosis captured by quick freezing and correlated with quantal transmitter release. J Cell Biol. 1979;81:275–300. doi: 10.1083/jcb.81.2.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh JK, Silinsky EM, Solsona CS. The role of cyclic AMP and its protein kinase in mediating acetylcholine release and the action of adenosine at frog motor nerve endings. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;101:311–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb12707.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoi N, Sakaba T, Neher E. Quantitative analysis of calcium-dependent vesicle recruitment and its functional role at the calyx of Held synapse. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14286–14298. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4122-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CC, Hsu KS. Presynaptic mechanism underlying cAMP-induced synaptic potentiation in medial prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:846–856. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.018093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn R, Sudhof TC. Membrane fusion and exocytosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:863–911. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko M, Takahashi T. Presynaptic mechanism underlying cAMP-dependent synaptic potentiation. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5202–5208. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0999-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang G, Joseph JW, Chepurny OG, Monaco M, Wheeler MB, Bos JL, Schwede F, Genieser HG, GG Holz. Epac-selective cAMP analog 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP as a stimulus for Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release and exocytosis in pancreatic beta-cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8279–8285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211682200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kase H, Iwahashi K, Nakanishi S, Matsuda Y, Yamada K, Takahashi M, Murakata C, Sato A, Kaneko M. K-252 compounds, novel and potent inhibitors of protein kinase C and cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;142:436–440. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90293-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B. The Release of Neural Transmitter Substances. Liverpool, UK: University Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, Miledi R. Estimates of quantal content during “chemical potentiation” of transmitter release. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1979;205:369–378. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1979.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koushika SP, Richmond JE, Hadwiger G, Weimer RM, Jorgensen EM, Nonet ML. A post-docking role for active zone protein Rim. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:997–1005. doi: 10.1038/nn732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon S, Johnstone AF, Viele K, Cooper RL. Regulation of synaptic vesicles pools within motor nerve terminals during short-term facilitation and neuromodulation. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:662–671. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00580.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundh H. Effects of 4-aminopyridine on statistical parameters of transmitter release at the neuromuscular junction. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol. 1979;44:343–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1979.tb02341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maximov A, Shin OH, Liu X, Sudhof TC. Synaptotagmin-12, a synaptic vesicle phosphoprotein that modulates spontaneous neurotransmitter release. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:113–124. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200607021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan EM. The statistics of transmitter release at chemical synapses. In: Porter R, editor. Neurophysiology III. vol. 17. Baltimore, MD: Univ. Park Press; 1978. pp. 49–117. (International Review of Physiology Series) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan EM, Martin AR. Non-linear summation of endplate potentials in the frog and mouse. J Physiol. 1985;311:307–324. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiri U, Rahamimoff R. Activation of transmitter release by strontium and calcium ions at the neuromuscular junction. J Physiol. 1971;215:709–726. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto MD. Binomial analysis of quantal transmitter release at glycerol treated frog neuromuscular junctions. J Physiol. 1975;250:121–142. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molgo J, Lemeignan M, Lechat P. Effects of 4-aminopyridine at the frog neuromuscular junction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1977;203:653–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves G, Neef A, Lagnado L. The actions of barium and strontium on exocytosis and endocytosis in the synaptic terminal of goldfish bipolar cells. J Physiol. 2001;535:809–824. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00809.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne SL, Herreros J, Bastiaens PI, Schiavo G. Calcium-dependent oligomerization of synaptotagmins I and II. Synaptotagmins I and II are localized on the same synaptic vesicle and heterodimerize in the presence of calcium. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:59–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki N, Shibasaki T, Kashima Y, Miki T, Takahashi K, Ueno H, Sunaga Y, Yano H, Matsuura Y, Iwanaga T, Takai Y, Seino S. cAMP-GEFII is a direct target of cAMP in regulated exocytosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:805–811. doi: 10.1038/35041046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang ZP, Melicoff E, Padgett D, Liu Y, Teich AF, Dickey BF, Lin W, Adachi R, Sudhof TC. Synaptotagmin-2 is essential for survival and contributes to Ca2+ triggering of neurotransmitter release in central and neuromuscular synapses. J Neurosci. 2006;26:13493–13504. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3519-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyle RA, Schivell AE, Hidaka H, Bajjalieh SM. Phosphorylation of synaptic vesicle protein 2 modulates binding to synaptotagmin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17195–17200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000674200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redman RS, Searl TJ, Hirsh JK, Silinsky EM. Opposing effects of phorbol esters on transmitter release and calcium currents at frog motor nerve endings. J Physiol. 1997;501:41–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.041bo.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redman S. Quantal analysis of synaptic potentials in neurons of the central nervous system. Physiol Rev. 1990;70:165–198. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J. Estimation of parameters for a model of transmitter release at synapses. Biometrics. 1976;32:61–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaba T, Neher E. Preferential potentiation of fast-releasing synaptic vesicles by cAMP at the calyx of Held. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:331–336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021541098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searl TJ, Silinsky EM. Increases in acetylcholine release produced by phorbol esters are not mediated by protein kinase C at motor nerve endings. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:247–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searl TJ, Silinsky EM. Evidence for two distinct processes in the final stages of neurotransmitter release as detected by binomial analysis in calcium and strontium solutions. J Physiol. 2002;539:693–705. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searl TJ, Silinsky EM. Phorbol esters and adenosine affect the readily releasable neurotransmitter pool by different mechanisms at amphibian motor nerve endings. J Physiol. 2003;553:445–456. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.051300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seino S, Shibasaki T. PKA-dependent and PKA-independent pathways for cAMP-regulated exocytosis. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:1303–1342. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin OH, Rhee JS, Tang J, Sugita S, Rosenmund C, Sudhof TC. Sr2+ binding to the Ca2+ binding site of the synaptotagmin 1 C2B domain triggers fast exocytosis without stimulating SNARE interactions. Neuron. 2003;37:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01145-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silinsky EM. On the calcium receptor that mediates depolarization-secretion coupling at cholinergic motor nerve terminals. Br J Pharmacol. 1981;73:413–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1981.tb10438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silinsky EM. The biophysical pharmacology of calcium dependent acetylcholine release. Pharmacol Rev. 1985;37:81–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silinsky EM, Searl TJ. Phorbol esters and neurotransmitter release; more than just protein kinase C? Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:1191–1201. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaoki T, Nomoto H, Takahashi I, Kato Y, Morimoto M, Tomita F. Staurosporine, a potent inhibitor of phospholipid/Ca2+dependent protein kinase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1986;135:397–402. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(86)90008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudeau LE, Emery DG, Haydon PG. Direct modulation of the secretory machinery underlies PKA-dependent synaptic facilitation in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1996;17:789–797. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viele K, Stromberg AJ, Cooper RL. Estimating the number of release sites and probability of firing within the nerve terminal by statistical analysis of synaptic charge. Synapse. 2003;47:15–25. doi: 10.1002/syn.10141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Chicka MC, Bhalla A, Richards DA, Chapman ER. Synaptotagmin VII is targeted to secretory organelles in PC12 cells, where it functions as a high-affinity calcium sensor. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:8693–8702. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.19.8693-8702.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Mashimo T, Sudhof TC. Synaptotagmin-1, -2, and -9: sensors for fast release that specify distinct presynaptic properties in subsets of neurons. Neuron. 2007;54:567–581. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong N, Zucker RS. cAMP acts on exchange protein activated by cAMP/cAMP-regulated guanine nucleotide exchange protein to regulate transmitter release at the crayfish neuromuscular junction. J Neurosci. 2005;25:208–214. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3703-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.