Abstract

The ancient and ubiquitous aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases constitute a valuable model system for studying early evolutionary events. So far, the evolutionary relationship of tryptophanyl- and tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (TrpRS and TyrRS) remains controversial. As TrpRS and TyrRS share low sequence homology but high structural similarity, a structure-based method would be advantageous for phylogenetic analysis of the enzymes. Here, we present the first crystal structure of an archaeal TrpRS, the structure of Pyrococcus horikoshii TrpRS (pTrpRS) in complex with tryptophanyl-5′ AMP (TrpAMP) at 3.0 Å resolution which demonstrates more similarities to its eukaryotic counterparts. With the pTrpRS structure, we perform a more complete structure-based phylogenetic study of TrpRS and TyrRS, which for the first time includes representatives from all three domains of life. Individually, each enzyme shows a similar evolutionary profile as observed in the sequence-based phylogenetic studies. However, TyrRSs from Archaea/Eucarya cluster with TrpRSs rather than their bacterial counterparts, and the root of TrpRS locates in the archaeal branch of TyrRS, indicating the archaeal origin of TrpRS. Moreover, the short distance between TrpRS and archaeal TyrRS and that between bacterial and archaeal TrpRS, together with the wide distribution of TrpRS, suggest that the emergence of TrpRS and subsequent acquisition by Bacteria occurred at early stages of evolution.

INTRODUCTION

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs) are a family of enzymes that play a vital role in maintaining the fidelity of transferring the genetic information from mRNA to protein in protein synthesis (1). They catalyze the aminoacylation reaction by first activating amino acids to form aminoacyl-AMPs and then attaching the activated amino acids to the 3′-end of their cognate tRNAs to form aminoacyl-tRNAs. These aminoacyl-tRNAs further recognize the trinucleotide codons of mRNA through the complementary anticodons on tRNAs during the protein synthesis. Since the amino acid sequence of a protein determines its structure and further function(s), errors in the aminoacylation reaction that result in incorrect incorporation of amino acids during protein synthesis can lead to serious consequences. Due to their importance, aaRSs have been suggested to be the first group of enzymes to evolve from the ancient ‘RNA world’ to the present ‘protein world’. Being ancient and ubiquitous, aaRSs are good candidates for studying early evolutionary events and hence have been subjects of intense interest (2).

aaRSs form two mutually exclusive classes with different structural architectures and aminoacylation mechanisms which are suggested to evolve from two distinct ancestors as a result of convergent evolution (3,4). Each of the two classes of aaRSs encompasses three subclasses and the members of each subclass are more closely related to each other than to others in the same class (5). So far, the evolutionary relationship between TrpRS and TyrRS, the only two members of subclass Ic, remains controversial. TrpRS and TyrRS are found to be closely related as crystal structures of Bacillus stearothermophilus TrpRS and TyrRS significantly resemble each other despite their low sequence similarity (6,7). Moreover, some mutants of Bacillus subtillis TrpRS lost the discrimination against Tyr, suggesting a close evolutionary relationship between TrpRS and TyrRS (8). In 1996, Ribas de Pouplana et al. (9) investigated the phylogenetic relationship of TrpRS and TyrRS based on a multiple sequence alignment of 16 bacterial and eukaryotic sequences available at that time and found that the two types of enzymes were clustered according to their bacterial or eukaryotic nature but not amino acid specificity. However, when Brown et al. (10) conducted a similar analysis with 32 sequences from a broader range of taxa in 1997, a contradictory conclusion was drawn as TrpRSs and TyrRSs form separate clades on the basis of amino acid specificity, which was considered to be attributed to the inclusion of sequences from more species especially those from Archaea. One year later, Diaz-Lazcoz et al. (11) performed a similar study with all available sequences of aaRSs including 49 TrpRS and TyrRS sequences. The pyramidal classification of the sequences implies that the archaeal/eukaryotic TyrRSs resemble more to the archaeal/eukaryotic TrpRSs than to their bacterial counterparts, which is in accord with part of the observations by Ribas de Pouplana et al. (9). On the other hand, their results also partially support the notion by Brown et al. as bacterial TrpRSs were grouped with archaeal/eukaryotic TrpRSs in the pyramidal classification and the constructed combined phylogenetic trees of TrpRS and TyrRS seemed to have more similarities with those generated by Brown et al. (10). The subsequent work by Woese et al. showed that the full canonical pattern holds for either enzyme, although the phylogenetic relationship between TrpRS and TyrRS was not assessed (2). Later, Yang et al. suggested that the amino acid specificities of TrpRS and TyrRS were established in the early stages of bacterial evolution (12).

All the aforementioned studies were based on the multiple sequence alignment method. However, our analysis of the TrpRS and TyrRS sequences using NCBI BLAST shows that the sequence identities between TrpRSs and TyrRSs and those between eukaryotic TrpRSs/TyrRSs and their bacterial counterparts are under 20% which is below the twilight zone threshold (13), and hence the sequence alignment method is less reliable for phylogenetic study of these enzymes. It is well known that for homologous proteins 3D structures and structural features are more conserved than primary sequences, and thus protein structures also provide useful evolutionary information especially when the sequence homology is low (14–16). In 2003, O’Donoghue and Luthey-Schulten (17) investigated the evolutionary paths of aaRSs with a structural alignment method. Specifically, the analysis based on the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA) algorithm showed that TrpRS and TyrRS conform to the canonical pattern. However, in the UPGMA tree, the branching between Homo sapiens TyrRS (hTyrRS) (representing the archaeal type) and bacterial TrpRS is short, and the phylogenetic tree based on the neighbor-joining (NJ) algorithm controversially grouped hTyrRS with bacterial TrpRS. The ambiguity was suggested to be attributed to the lack of crystal structures of archaeal/eukaryotic TrpRSs (17).

During the past several years, with the rapid development of structural biology and structural genomics, increasingly more crystal structures of aaRSs have been determined, including those of TrpRSs from Eucarya (12,18) and more TyrRSs from Archaea (19). However, by the time this study was initiated, no structure of TrpRS from Archaea was available. Thus, we were motivated to solve the crystal structure of Pyrococcus horikoshii TrpRS (pTrpRS) and employ the structural information for further evolutionary study. Here, we report the crystal structure of pTrpRS in complex with tryptophanyl-5′ AMP (TrpAMP), the first archaeal TrpRS structure, and present the results of a more complete structure-based phylogenetic analysis of TrpRS and TyrRS which for the first time includes structures from species representing all three domains of life. Our data suggest the origination of TrpRS from archaeal TyrRS and the subsequent horizontal transfer of TrpRS from Archaea to Bacteria, providing new insights into the evolutionary paths of TrpRS and TyrRS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning, expression and purification

The P. horikoshii genomic DNA was used as the template to amplify the trpS1 gene. The gene fragment was inserted into the NcoI and SacI restriction sites of the pET28a expression vector (Novagen) which adds a hexahistidine tag at the C-terminus of the protein product. Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3) was transformed with the plasmid and when OD600 of the transformed cells reached 0.6∼0.8, 1 mM IPTG was added to induce protein expression at 37°C for 4 h. The cells were harvested, followed by sonication in the lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4, pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 1mM PMSF). The supernatant fraction of the lysate was applied onto a Ni-affinity column (Qiagen) pre-equilibrated with the lysis buffer, and then the column was loaded in turn with the washing and elution buffers (the lysis buffer supplemented with 30 and 200 mM imidazole, respectively). The eluted fractions were dialyzed against the dialysis buffer (20 mM bicine buffer, pH 9.0, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol and 1 mM PMSF) and concentrated to 20 mg/ml for crystallization screening.

Crystallization, data collection, structure determination and refinement

Prior to crystallization screening the purified protein was heated at 70°C for 10 min followed by centrifugation at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and 2 µl of the protein solution was mixed with 2 µl of the crystallization solution to form crystallization drops. The crystallization process was carried out at 20°C using hanging drop vapor diffusion method and crystals grew from drops containing the protein solution and the crystallization solution [0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 5.2, 1.6 M (NH4)2SO4 and 10 mM MnCl2] supplemented with 0.5 µl of 20 mM Trp and 0.5 µl of 100 mM ATP.

X-ray diffraction data were collected from a flash-cooled crystal at synchrotron beamline BL17A of Photon Factory, Japan and processed using the HKL2000 software package (20). The structure of pTrpRS was solved by the molecular replacement method with program PHASER (21) [implemented in the CCP4 suite (22)] using the structure of hTrpRS in complex with TrpAMP [PDB code 2QUJ, (23)] as the search model. There are two monomers in an asymmetric unit forming a homodimer and the monomers were refined independently. In the initial difference Fourier maps, there are evident electron densities corresponding to a bound TrpAMP at each active site (Figure 1B). This is consistent with the previous results that in the presence of Trp and ATP, the Trp activation reaction took place in the crystrallization solution, leading to the formation of TrpAMP (23). The initial structure refinement was carried out with the program CNS (24) following the standard protocols and the model building was performed manually with the help of programs COOT (25) and O (26). The final structure refinement was performed using the maximum likelihood algorithm implemented in the program REFMAC5 (27). Throughout the refinement, a free R-factor monitor calculated with 5% of randomly chosen reflections and a bulk solvent correction were applied. The summary of statistics of the diffraction data and the structure refinement is listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

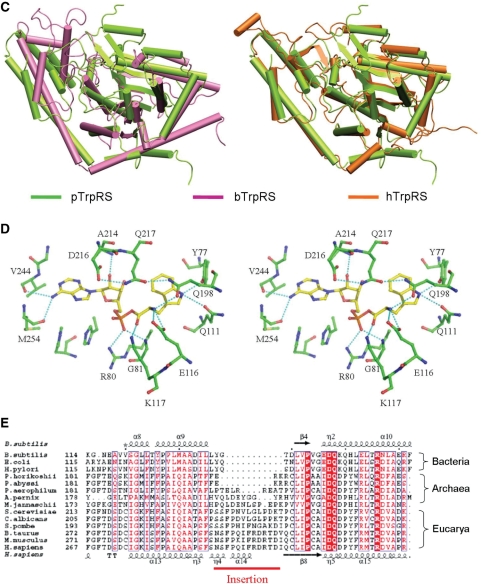

Structure of pTrpRS in complex with TrpAMP. (A) Overall structure of the pTrpRS–TrpAMP complex. There are two pTrpRS–TrpAMP complexes in an asymmetric unit forming a homodimer. For clarity, only one monomer is shown with the N-terminal domain in yellow, the RF catalytic domain in cyan and the C-terminal domain in green. The four characteristic motifs, namely the N-terminal β-hairpin, AIDQ motif, HIGH motif and KMSAS loop are marked and colored in orange, purple, red and violet, respectively. The bound TrpAMP molecules are shown in ball-and-stick models. (B) A representative SIGMMA-weighted 2Fo−Fc composite omit map (1σ contour level) for the bound TrpAMP. (C) Structural comparisons of pTrpRS with hTrpRS (left panel) and bTrpRS (right panel) based on a superposition of the core region of the RF domain (equivalent to residues 74–229 of pTrpRS). The structures of the pTrpRS–TrpAMP, hTrpRS–TrpAMP (PDB code 2QUJ) and bTrpRS–TrpAMP (PDB code 1I6M) complexes are shown in green, orange and magenta, respectively. (D) A stereoview showing interactions of the bound TrpAMP (yellow) with the surrounding residues (green) at the active site. The hydrogen-bonding interactions are indicated with thin dashed lines. (E) Sequence alignment of the insertion region of TrpRSs from different species representing all three domains Bacteria, Archaea and Eucarya. The insertion region (equivalent to residues 204–209 of pTrpRS) is labeled and marked with a red line. The sequence alignment is generated by ESPript (47) with the secondary structures of bTrpRS and hTrpRS at the top and bottom of the alignment, respectively. The invariant residues are highlighted in shaded red boxes while the conserved ones in open red boxes.

Table 1.

Statistics of X-ray diffraction data and structure refinement

| Diffraction data statistics | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50.0–3.0 (3.1–3.0)a |

| Space group | P213 |

| Cell parameters a = b = c (Å) | 170.9 |

| Number of observed reflections | 513 040 |

| Number of unique reflections (I/σ >0) | 33 131 |

| Redundancy | 15.5 (10.3) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (99.5) |

| I/σ (I) | 33.1 (2.6) |

| Rmerge (%)b | 8.8 (78.8) |

| Mosaicity | 0.3 |

| Refinement and structure model statistics | |

| Number of reflections [Fo > 0σ(Fo)] | 33 089 |

| Working set | 31 439 |

| Free R set | 1650 |

| R-factorc | 0.238 |

| Free R-factorc | 0.258 |

| Subunits/ASU | 2 |

| Total number of protein residues | 716 |

| Average B-factor of all atoms (Å2) | 79.7 |

| Protein main-chain atoms | 79.9 |

| Protein side-chain atoms | 79.6 |

| Ligand atoms | 44.2 |

| RMSD bond lengths (Å) | 0.008 |

| RMSD bond angles (°) | 1.0 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |

| Most favored regions | 92.6 |

| Allowed | 7.2 |

| Generously allowed | 0.2 |

aThe numbers in parentheses refer to the highest resolution shell.

b

cR-factor = Σ||Fo|−|Fc||/Σ |Fo|.

Structural alignment and phylogenetic analysis

Among the TrpRS and TyrRS structures available in the RCSB Protein Data Bank, there are multiple structures for a given enzyme in which the enzyme is in apo form or in complexes with various ligands. The previous structural studies have shown that both TrpRS and TyrRS undergo conformational changes upon ligand binding (6,7,19,23,28–33). For example, upon tryptophan binding, hTrpRS transforms from an open conformation of the unliganded form to a semi-closed conformation with the closure of the AIDQ motif and the KMSAS loop toward the active site followed by the rotation of the N- and C-terminal domains towards the Rossmann fold (RF) catalytic domain (23). In the presence of TrpAMP or TrpNH2O (a tryptophan analog) and ATP, the enzyme takes a closed conformation mainly with a further movement of the KMSAS loop toward the active site when compared with the semi-closed conformation (23). For bacterial Bacillus stearothermophilus TrpRS (bTrpRS), the enzyme converts from an open conformation in the unliganded state or in complex with Trp or ATP alone to a closed conformation in the pre-transition (in complex with TrpNH2O and ATP) and post-transition (in complex with AQP) states and further to a distinct closed conformation in the product state (in complex with TrpAMP) (6,28–31). For TyrRS, upon ligand binding, the overall structures of the enzymes remain similar and the conformational changes occur mainly at the KMSKS loop which rearranges during the reaction (19,32,33). For instance, depending on the binding of ligands, the KFGKT loop of the bacterial TyrRSs (equivalent to the KMSKS signature of TrpRSs) may take an open conformation (in the tyrosine-bound complexes), a semi-open conformation (in the TyrAMP/TyrAMS-bound complexes) or a closed conformation (in the presence of tyrosinol and ATP) (19,32,33). To ensure equal weight of the species in the structural alignment and to minimize the effect of conformational differences on the phylogenetic analysis, one structure of TrpRS/TyrRS was selected for each species and in particular, for a given enzyme that has multiple structures, the structure that is the most similar to that of the pTrpRS–TrpAMP complex is selected. In total, 6 TrpRS structures and 10 TyrRS structures were chosen in which the enzyme is complexed with either TrpAMP/TyrAMP (preferably) or Trp/Tyr. The chosen structures of TrpRSs include those of TrpRSs in complexes with TrpAMP from B. stearothermophilus (PDB code 1I6K), Mycoplasma pneumoniae (PDB code 2YY5), H. sapiens (PDB code 2QUJ) and P. horikoshii (reported herein), and with tryptophan from Deinococcus radiodurans (PDB code 1YI8) and Thermotoga maritima (PDB code 2G36). The chosen structures of TyrRSs include those of TyrRSs in complexes with TyrAMP or TyrAMS from B. stearothermophilus (PDB code 3TS1), E. coli (PDB code 1VBM), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (PDB code 2DLC) and human mitochondria (PDB code 2PID), with tyrosine or tyrosinol from P. horikoshii (PDB code 2CYC), Methanococcus jannaschii (PDB code 1J1U), Archeoglobus fulgidus (PDB code 2CYB), Thermus thermophilus (PDB code 1H3F) and H. sapiens (PDB code 1Q11), and with a Tyr analog from Staphylococcus aureus (PDB code 1JII).

Selection of appropriate region(s) is a key step for reliable structure-based phylogenetic analyses of aaRSs. Discrepancies may arise from incompleteness or dispersion of the crystal structures due to deletion, invisibility and/or significant conformational differences of the N- and C-termini or flexible regions, and from possible posterior evolution of the anticodon recognition domain and the N-terminal domain which are less conserved than the catalytic domain. Therefore, in our structural alignment, we selected only the core region of the conserved RF domain (corresponding to residues 74–229 of pTrpRS) which is structurally conserved and adopts similar conformations in all of the selected structures. The region is almost identical to that used in the sequence-based phylogenetic study by Brown et al. (10) (equivalent to residues 71–257 of pTrpRS) except that the KMSKS loop which adopts different conformations depending on the binding of different ligands (see above) was not included in our study. The sequence identities of this region between TrpRSs and TyrRSs remain below the twilight zone threshold (13), again underscoring the advantage of the utilization of the structural alignment method in our study. Similarly, only the RF domains were aligned in the structure-based phylogenetic study of class I aaRSs by O’Donoghue and Luthey-Schulten (17) although the exact region was not specified.

The structural alignment was carried out using the multiple structural alignment program STAMP integrated in the molecular visualization program VMD, version 1.8.5 (34) with the parameters npass = 2, scanscore = 6 and scanslide = 5. Protein homology was assessed with the structural similarity measure QH which was adapted by O’Donoghue et al. (17) on the basis of the original measure Q (35) to include the effects of the gaps on the aligned portion. QH ranges from 0 to 1, where QH = 1 means that the two proteins are identical. A distance matrix of pairwise structure dissimilarity value (1−QH) was generated (Table 2) and used as input for phylogenetic analyses with the UPGMA method using software MultiSeq in VMD (36), and with the NJ algorithm and the minimum evolution (ME) method, respectively, using program Mega4 (37).

Table 2.

Distance (1−QH) matrix for UPGMA, NJ and ME dendrogram of subclass Ic aaRSsa

| W-B.stearothermophilus | 0.00 | |||||||||||||||

| W2-D.radiodurans | 0.24 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||||

| W-H.sapiens | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.00 | |||||||||||||

| W-M.pneumoniae | 0.14 | 0.25 | 0.39 | 0.00 | ||||||||||||

| W-P.horikoshii | 0.33 | 0.36 | 0.19 | 0.34 | 0.00 | |||||||||||

| W-T.maritima | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.21 | 0.35 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| Y-T.thermophilus | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.00 | |||||||||

| Ym-H.sapiens | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.00 | ||||||||

| Y-M.jannaschii | 0.36 | 0.35 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.00 | |||||||

| Y-P.horikoshii | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Y-A.fulgidus | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.43 | 0.37 | 0.41 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.00 | |||||

| Y-B.stearothermophilus | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.38 | 0.21 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.41 | 0.00 | ||||

| Y-E.coli | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.23 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.44 | 0.08 | 0.00 | |||

| Y-S.aureus | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.48 | 0.41 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.00 | ||

| Y-S.cerevisiae | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.44 | 0.00 | |

| Y-H.sapiens | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.21 | 0.43 | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.06 | 0.00 |

aDesignation of the enzymes is the same as in Figure 2.

RESULTS

Structure of the pTrpRS–TrpAMP complex

The crystal structure of the pTrpRS–TrpAMP complex was determined at 3.0 Å resolution with an R-factor of 23.8% and a free R-factor of 25.8% (Table 1). The asymmetric unit contains two pTrpRS molecules each bound with a TrpAMP at the active site (Figure 1A). pTrpRS consists of three typical domains: an N-terminal domain (residues 1–68), an RF catalytic domain (residues 69–246 and 358–386) and a C-terminal α-helical domain (residues 247–357) [hereafter the nomenclature of the secondary structures of pTrpRS is after Yang et al. (38)]. Most of the residues are well defined with good electron density except the N-terminal three residues and residues 281–300.

Superposition of the structure of the pTrpRS–TrpAMP complex to the corresponding structures of eukaryotic hTrpRS (23) and bacterial bTrpRS (29) yields root mean square deviations of 1.4 and 2.6 Å, respectively, for all Cα atoms (Figure 1C), indicating that the overall structure of pTrpRS resembles more to hTrpRS than bTrpRS, which is consistent with its higher sequence similarity with hTrpRS than with bTrpRS (44% versus 23%). In addition, the archaeal pTrpRS has an N-terminal domain which is approximately as long as that of the T1 form hTrpRS (39), whereas this domain is absent in bTrpRS. This domain contains a β-hairpin (residues 5–13P) (hereafter the residues of aaRSs from P. horikoshii, H. sapiens and B. stearothermophilus are indicated with superscripted letters P, H and B, respectively) and the equivalent β-hairpin of hTrpRS has been shown to be important to the ATP binding (23,38). Within the β-hairpin a salt bridge between Lys6P and Glu11P (equivalent to Phe84H and Thr89H) appears to stabilize the region in the extreme environment of high temperature.

TrpAMP is bound at the active site which is composed by key structural elements including the KMSAS, HIGH and AIDQ motifs. The amino acid specificity of pTrpRS is mainly determined by residues Gln111P and Tyr77P (equivalent to Gln194H and Tyr159H, respectively). The nitrogen of the indole ring of the tryptophanyl moiety forms hydrogen bonds with the side-chain carbonyl oxygen of Gln111P (3.2 Å) and the hydroxyl oxygen of Tyr77P (2.8 Å) (Figure 1D). Additionally, the indole ring is stabilized by the phenol group of Tyr77P via π−π stacking interaction. The amino group of the tryptophanyl moiety is bound by Glu116P (equivalent to Glu199H) via a salt bridge and Gln198P (equivalent to Gln284H) via a hydrogen bond (3.0 Å) through their side-chains, while the carbonyl group interacts with the side-chain amino of Lys117P (equivalent to Lys200H) (3.1 Å).

The binding mode of the tryptophanyl moiety by archaeal pTrpRS is quite similar to that by eukaryotic hTrpRS, and together the archaeal and eukaryotic TrpRSs show great differences from bacterial bTrpRS. In the bTrpRS–TrpAMP complex, the indole nitrogen of the tryptophanyl moiety is recognized by Asp132B via a hydrogen bond and Phe5B via hydrophobic interaction (29). In addition, the amino group and the carbonyl group are bound by Tyr125B and Gln9B, respectively. Among the residues of bTrpRS participating in the Trp binding, only Phe5B has similar physicochemical properties as its equivalent in archaeal/eukaryotic TrpRSs (Tyr77P/Tyr159H) although the hydrogen-bonding interaction between the indole nitrogen and Tyr77P/Tyr159H is absent in the bTrpRS complex. In addition, the interaction between the amino group and Gln198P/Gln284H observed in the pTrpRS/hTrpRS complexes is also missing in the bTrpRS complex.

For the AMP group, the N6 atom of the adenosine moiety of TrpAMP is recognized by the main-chain carbonyl groups of Val244P and Met254P of the KMSAS motif. The ribose group is positioned by the AIDQ motif with the 2′-hydroxyl group interacting with the side-chain carboxylate of Asp216P and both the 2′-hydroxyl and 3′-hydroxyl groups interacting with the main-chain nitrogen of Ala214P. Considering that the AIDQ motif is highly conserved in Archaea/Eucarya and the corresponding GEDQ motif of bTrpRS binds to AMP with equivalent interactions (29), the binding mode of AMP seems to be conserved in all TrpRSs. As for the α-phosphate, Lys195B of the KMSKS loop in bTrpRS binds it; however, due to the lack of a lysine at the equivalent position, the moiety is bound by the side-chain amino of Arg80P/Arg162H and the main-chain amide of Gly81P/Gly163H on a distal strand β5.

Although the overall structure and the TrpAMP binding mode of pTrpRS are more similar to those of hTrpRS than to bTrpRS, the dimer interface of pTrpRS resembles more to that of bTrpRS. The dimer interface of pTrpRS buries 1877 Å2 (or 10%) solvent-accessible surface of each monomer and involves five α-helices (α8 and α10-α13) of the RF domain and the C-terminus. Compared with pTrpRS and bTrpRS, hTrpRS has an insertion (residues 290–305) in the RF domain (Figure 1E) that forms η4 and α14 and blocks the extension of the C-terminus to the dimerization interface. The equivalent regions of pTrpRS (residues 204–209) and bTrpRS (residues 135–139) are much shorter and the C-terminus can extend towards the other subunit, which substantially increases the dimer interface (1877 Å2 in pTrpRS /2060 Å2 in bTrpRS versus 1501 Å2 in hTrpRS). It is also noteworthy that, compared with hTrpRS or bTrpRS, pTrpRS contains four additional pairs of inter-molecular salt bridges at the dimer interface formed between Glu163P and Lys130P and between Glu185P and Lys178P, respectively. As the formation of more salt bridges is one of the features of thermo-stable proteins, these additional salt bridges may contribute to the hyperthermostability of pTrpRS.

Structural alignment of TrpRS and TyrRS

Protein structures are more conserved than sequences and thus contain evolutionary information. Comparative studies of different structures of several enzymes have been carried out to investigate their evolutionary paths (17,40). Previously, the evolutionary relationship between TrpRS and TyrRS was examined using a structural alignment method by O’Donoghue et al. (17). In their work, different algorithms rendered conflicting results about the branching of archaeal/eukaryotic TyrRS: in the UPGMA tree, archaeal/eukaryotic TyrRS (represented by H. sapiens TyrRS) clustered with its bacterial counterparts, while in the NJ tree it grouped with the enzymes with specificity to tryptophan. The discrepancy was attributed to the unavailability of a crystal structure of TrpRS from Archaea/Eucarya at that time, which could cause errors arising from ‘attraction effects’ between long uninterrupted branches (41). With the structure of pTrpRS presented here, we can now perform a more complete study to get a more reliable picture of the evolutionary history of TrpRS and TyrRS.

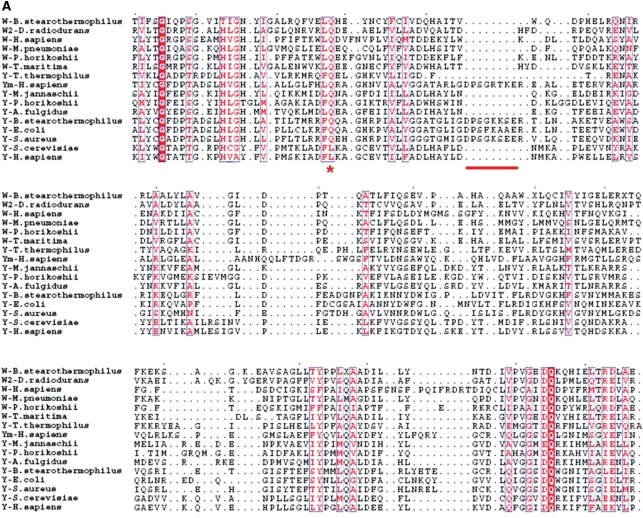

To prevent discrepancies arising from incompleteness or dispersion of the crystal structures and to avoid bias caused by posterior evolution of certain regions, we selected the core region of the RF domain for the structural alignment (for details see ‘Materials and Methods’ section). In our study, this region can be accurately aligned and the gaps and insertions can be unambiguously identified (Figure 2A). In contrast, in a previous study that was based on sequence alignment of a similar region alone without utilization of the structural information, certain residues/regions were not properly aligned (10). For example, a structurally conserved Gln residue corresponding to Gln101P on β6 of pTrpRS (Figure 2A) which participates in the interactions of β6 with several other structural elements of the RF domain, is incorrectively aligned in the sequence-based study (10). In addition, a part of an α-helix in the archaeal/eukaryotic TyrRSs (corresponding to residues Pro86 to Leu92 of human TyrRS) which should be aligned to its equivalent helix (corresponding to residues Thr93 to Glu99 of E. coli TyrRS) (Figure 2A), was mistakenly aligned to a loop in the bacterial TyrRSs (corresponding to residues Ala86 to Asn92 of E. coli TyrRS) (10). Thus, the missing of an equivalent loop in the archaeal/eukaryotic TyrRSs (indicated by a gap in Figure 2A) was not detected. In a later phylogenetic study based on multiple sequence alignment, the structural information was applied to adjust the sequence alignment of B. stearothermophilus TrpRS and TyrRS and subsequently all other sequences (11). The utilization of the structural information obviously improved the quality and reliability of the multiple sequence alignment in that the aforementioned Gln residue became properly aligned. However, the gap was still undistinguished, which is possibly limited by the availability of only two crystal structures of TrpRS and TyrRS (those from B. stearothermophilus) at that time. Intriguingly, the application of different sequence alignment methods (10,11) in the two phylogenetic studies yielded inconsistent results about the classification of TrpRSs and TyrRSs, with the latter in agreement with our result (see ‘Discussion’ section later), indicating that whether structural information is considered and introduced in the alignments may account for the divergence in the positioning of archaeal/eukaryotic TyrRSs in the evolutionary trees.

Figure 2.

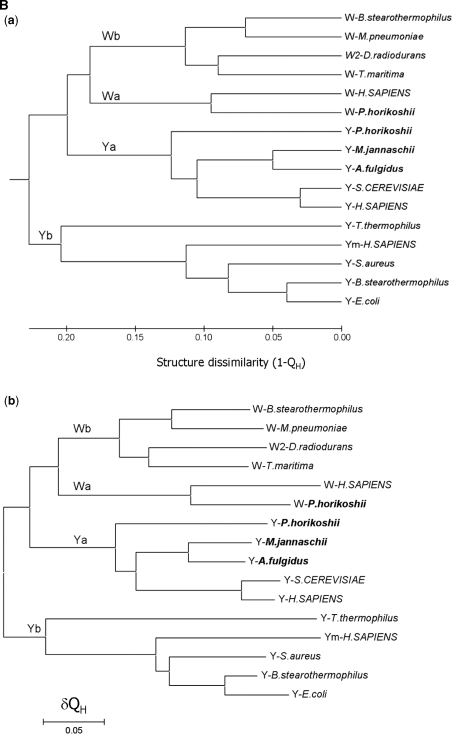

Structure-based phylogenetic analysis of TrpRS and TyrRS. (A) Structural alignment of the core region of the RF domain of the selected synthetases. The structural aligment was performed by using the program STAMP. For simplicity, the synthetases are denoted with the amino acid specificity of the enzyme (W for TrpRS, W2 for the type II TrpRS, Y for TyrRS and Ym for mitochondrial TyrRS) followed by the name of the organism. The strictly conserved residues are highlighted in shaded red boxes and the conserved in open red boxes. A structurally conserved Gln residue (corresponding to Gln101P on strand β6 of pTrpRS) is properly aligned and denoted with an asterisk. A gap in the structures of archaeal and eukaryotic TyrRSs is identified and indicated with a solid line. (B) Phylogenetic trees of TyrRS and TrpRS. A distance matrix of pairwise structure dissimilarity value (1−QH) calculated with the result of the structural alignment of TrpRSs and TyrRSs was used to generate the phylogenetic trees with (a) UPGMA, (b) NJ and (c) ME algorithms. Designation of the enzymes is the same as in Figure 2A. Organisms from Eucarya are in uppercase, those from Archaea in bold, and those from Bacteria in plain text. The branchings of bacterial TrpRS (Wb), archaeal TrpRS (Wa), bacterial TyrRS (Yb) and archaeal TyrRS (Ya) are shown.

Structure-based phylogenetic analysis of TyrRS and TrpRS

With the inclusion of the pTrpRS structure and the other recently reported TrpRS and TyrRS structures, the structure-based evolutionary trees were generated with the UPGMA and NJ algorithms which have been used by O’Donoghue and Luthey-Schulten (17), and additionally the ME algorithm which is commonly used for distance-based analyses. Although the UPGMA algorithm assumes the molecular clock hypothesis, the phylogenetic trees calculated with the UPGMA, ME and NJ algorithms, respectively, show a congruent topology (Figure 2B). The root of the TrpRS tree separates the archaeal/eukaryotic TyrRSs and their bacterial counterparts. The archaeal/eukaryotic TyrRSs group with TrpRSs without ambiguity, which is in accord with the observations by both Ribas de Pouplana et al. (9) and Diaz-Lazcoz et al. (11) that the archaeal and eukaryotic TyrRSs resemble more to TrpRSs than their bacterial counterparts (see ‘Discussion’ section later).

When examined individually, TrpRSs conform to the full canonical pattern (Figure 2B). According to Woese et al. (2), at least six distinct subgroups can be identified within the bacterial genre (2). Here, only four structures of TrpRSs from bacterial species are available and included in the analysis, representing four subgroups of the bacterial genre. In our evolutionary trees, TrpRSs from B. stearothermophilus [closely related to B. subtillis whose sequence was included in the work by Woese et al. (2)] and M. pneumoniae cluster together while TrpRS from T. maritima is more closely related to that from D. radiodurans, consistent with the evolutionary relationships of the subtypes revealed by Woese et al. (2). Although the bacterial TrpRSs show great divergence, they form a group distinct from the archaeal and eukaryote TrpRSs represented by the enzymes from P. horikoshii and H. sapiens, respectively, suggesting that the division between bacterial TrpRSs and archaeal/eukaryotic TrpRSs occurred at an early stage of bacteria evolution.

For TyrRSs, the generated evolutionary trees essentially have the same topology as the previously reported sequence-based trees (2,42), which all strongly support the distinct separation of Bacteria, Archaea and Eucarya (Figure 2B). In the bacterial genre, TyrRSs are divided into two far related subtypes, namely TyrRS and TyrRZ, with TyrRSs from B. stearothermophilus, E. coli and S. aureus belonging to the TyrRS subgroup and that from T. thermophilus belonging to the other. These results support the notion that bacterial TyrRSs can be divided into TyrRS and TyrRZ, which was originally indicated by the sequence-based phylogenetic studies (43,44). Additionally, human mitochondrial TyrRS is more similar to the bacterial enzymes of the first subtype. TyrRSs from A. fulgidus and M. jannaschii cluster with eukaryotic TyrRSs, while that from P. horikoshii forms a seperate branch, although they are all from Euryarchaeota. Considering that P. horikoshii TyrRS clusters with TyrRSs from plants in the sequence-based trees (2), our results suggest that TyrRSs are partially intermixed in the archaeal and eukaryotic genre. To verify this notion, further study is needed to include more structures of eukaryotic TyrRSs especially those from plants.

DISCUSSION

As the sequence identity between TrpRS and TyrRS is below the twilight zone threshold (13), the connections of the two enzymes suggested by the previous sequence-based phylogenetic studies are controversial. For proteins sharing low sequence identity, 3D structures are better than primary sequences for modeling of protein evolution (15–17). In particular, despite the low sequence homology, TyrRS and TrpRS share high structure similarity, supporting the use of the structural alignment method for phylogenetic studies of these enzymes. However, due to the limitation of available crystal structures of TrpRS and TyrRS, the structure-based study of aaRSs by O’Donoghue and Luthey-Schulten (17) yielded conflicting results and thus was unsuccessful to give a conclusive answer regarding the evolutionary relationship between TrpRS and TyrRS (17). In our study, we demonstrate the advantage of the structural alignment method over the sequence alignment method by showing that the residues are correctly aligned and the insertions and gaps are unambiguously identified (Figure 2A). In addition, we achieve consistent results as shown by the congruent topology of the generated phylogenetic trees (Figure 2B). Therefore, our results are more accurate and valuable to discern the evolution history of the two enzymes. This strategy can also be applied to examine the relationships between other aaRSs as the sequence identities of aaRSs with different specificities are typically below the twilight zone threshold (17).

Analysis of a set of paralogs of aaRSs has suggested that generally aaRSs form monophyletic groups regarding their amino acid specificities, implying that the enzymes appeared prior to the separation of the three kingdoms (2). However, several exceptions exist: asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase (AsnRS) and glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase (GlnRS) are suggested to arise from the archaeal genre of aspartyl-tRNA synthetase (AspRS) (2,45) and the eukaryotic lineage of glutamyl-tRNA synthetase (GluRS) (2,46), respectively. In the structural dendrograms presented in Figure 2B, the root of TrpRS is located in the archaeal branch of TyrRS, making the TyrRS group paraphyletic and thus breaking the monophyletic rule. These results indicate that similar to AsnRS, TrpRS originates from an archaeal linage. Despite the same achaeal origin, the evolutionary path of TrpRS exhibits some differences from that of AsnRS. The branching between archaeal AsnRS and archaeal AspRS is relatively long, suggesting that the appearance of archaeal AsnRS and the subsequent acquisition of bacterial AsnRS occurred at late stages, which explains the absence of AsnRS in most archaeal and some of the bacterial taxa (2). In contrast, the relatively short distance between TrpRS and archaeal TyrRS and that between bacterial TrpRS and archaeal TrpRS suggest that TrpRS had already emerged right after the division between Bacteria and Archaea and soon horizontally transferred to the bacterial genre, which is also supported by the fact that TrpRS is widely distributed in all three kingdoms. The transfer of TrpRS from Archaea into Bacteria is consistent with the notion by Woese et al. (2) that the horizontal gene transfer of aaRSs between Archaea and Bacteria appears to be asymmetric as the synthetases were transferred only from Archaea to Bacteria, but not the reverse. On the other hand, the close occurrences of the two events (appearance of TrpRS and the acquisition by the bacterial genre) might be another reason for the divergence of the positioning of archaeal TrpRS in the previous evolutionary studies (9–12,17).

Collectively, our data imply that before the division of Bacteria and Archaea, the ancestor TyrRS had existed, whereas no aminoacyl synthetase ancestor solely with a Trp specificity was present. After the division between Bacteria and Archaea, the ancestor of TyrRSs diverged to the archaeal version and the bacterial version, and soon TrpRSs evolved from the archaeal linage of TyrRS probably through gene duplication, followed by the early acquisition of TrpRSs by Bacteria through horizontal gene transfer.

Protein Data Bank accession code

The structure of tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase from P. horikoshii in complex with TrpAMP has been deposited with the RCSB Protein Data Bank under accession code 3JXE.

FUNDING

The Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2006AA02A313 and 2007CB914302); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30730028 and 30770480); the Chinese Academy of Sciences (KSCX2-YW-R-107 and SIBS2008002); Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (07XD14032 and 07ZR14131). Funding for open access charge: National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the staff members at Photon Factory, Japan for technical support in diffraction data collection and other members of our group for helpful discussion.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ibba M, Soll D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000;69:617–650. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woese CR, Olsen GJ, Ibba M, Soll D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, the genetic code, and the evolutionary process. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000;64:202–236. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.1.202-236.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eriani G, Delarue M, Poch O, Gangloff J, Moras D. Partition of tRNA synthetases into two classes based on mutually exclusive sets of sequence motifs. Nature. 1990;347:203–206. doi: 10.1038/347203a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagel GM, Doolittle RF. Phylogenetic analysis of the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. J. Mol. Evol. 1995;40:487–498. doi: 10.1007/BF00166617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cusack S. Eleven down and nine to go. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1995;2:824–831. doi: 10.1038/nsb1095-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doublie S, Bricogne G, Gilmore C, Carter CW., Jr Tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase crystal structure reveals an unexpected homology to tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase. Structure. 1995;3:17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brick P, Bhat TN, Blow DM. Structure of tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase refined at 2.3 Å resolution. Interaction of the enzyme with the tyrosyl adenylate intermediate. J. Mol. Biol. 1989;208:83–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Praetorius-Ibba M, Stange-Thomann N, Kitabatake M, Ali K, Soll I, Carter CW, Jr, Ibba M, Soll D. Ancient adaptation of the active site of tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase for tryptophan binding. Biochemistry. 2000;39:13136–13143. doi: 10.1021/bi001512t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ribas de Pouplana L, Frugier M, Quinn CL, Schimmel P. Evidence that two present-day components needed for the genetic code appeared after nucleated cells separated from eubacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:166–170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown JR, Robb FT, Weiss R, Doolittle WF. Evidence for the early divergence of tryptophanyl- and tyrosyl-tRNA synthetases. J. Mol. Evol. 1997;45:9–16. doi: 10.1007/pl00006206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diaz-Lazcoz Y, Aude JC, Nitschke P, Chiapello H, Landes-Devauchelle C, Risler JL. Evolution of genes, evolution of species: the case of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1998;15:1548–1561. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang XL, Otero FJ, Skene RJ, McRee DE, Schimmel P, Ribas de Pouplana L. Crystal structures that suggest late development of genetic code components for differentiating aromatic side chains. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:15376–15380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136794100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rost B. Twilight zone of protein sequence alignments. Protein Eng. 1999;12:85–94. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.2.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chothia C, Lesk AM. The relation between the divergence of sequence and structure in proteins. EMBO J. 1986;5:823–826. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gan HH, Perlow RA, Roy S, Ko J, Wu M, Huang J, Yan S, Nicoletta A, Vafai J, Sun D, et al. Analysis of protein sequence/structure similarity relationships. Biophys. J. 2002;83:2781–2791. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(02)75287-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balaji S, Srinivasan N. Comparison of sequence-based and structure-based phylogenetic trees of homologous proteins: inferences on protein evolution. J. Biosci. 2007;32:83–96. doi: 10.1007/s12038-007-0008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'D;onoghue P, Luthey-Schulten Z. On the evolution of structure in aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003;67:550–573. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.550-573.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu Y, Liu Y, Shen N, Xu X, Xu F, Jia J, Jin Y, Arnold E, Ding J. Crystal structure of human tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase catalytic fragment: insights into substrate recognition, tRNA binding, and angiogenesis activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:8378–8388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311284200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuratani M, Sakai H, Takahashi M, Yanagisawa T, Kobayashi T, Murayama K, Chen L, Liu ZJ, Wang BC, Kuroishi C, et al. Crystal structures of tyrosyl-tRNA synthetases from Archaea. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;355:395–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276A:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCoy AJ. Solving structures of protein complexes by molecular replacement with Phaser. Acta Cryst. 2007;D63:32–41. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906045975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collaborative Computational Project No. 4. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Cryst. 1994;D50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen N, Zhou M, Yang B, Yu Y, Dong X, Ding J. Catalytic mechanism of the tryptophan activation reaction revealed by crystal structures of human tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase in different enzymatic states. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:1288–1299. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Cryst. 1998;D54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Cryst. 2004;D60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Cryst. 1991;A47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Cryst. 1997;D53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ilyin VA, Temple B, Hu M, Li G, Yin Y, Vachette P, Carter CW., Jr 2.9 Å crystal structure of ligand-free tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase: domain movements fragment the adenine nucleotide binding site. Protein Sci. 2000;9:218–231. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.2.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Retailleau P, Yin Y, Hu M, Roach J, Bricogne G, Vonrhein C, Roversi P, Blanc E, Sweet RM, Carter CW., Jr High-resolution experimental phases for tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase (TrpRS) complexed with tryptophanyl-5′ AMP. Acta Cryst. 2001;D57:1595–1608. doi: 10.1107/s090744490101215x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Retailleau P, Huang X, Yin Y, Hu M, Weinreb V, Vachette P, Vonrhein C, Bricogne G, Roversi P, Ilyin V, et al. Interconversion of ATP binding and conformational free energies by tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase: structures of ATP bound to open and closed, pre-transition-state conformations. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;325:39–63. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Retailleau P, Weinreb V, Hu M, Carter CW., Jr Crystal structure of tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase complexed with adenosine-5′ tetraphosphate: evidence for distributed use of catalytic binding energy in amino acid activation by class I aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;369:108–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kobayashi T, Takimura T, Sekine R, Kelly VP, Kamata K, Sakamoto K, Nishimura S, Yokoyama S. Structural snapshots of the KMSKS loop rearrangement for amino acid activation by bacterial tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;346:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yaremchuk A, Kriklivyi I, Tukalo M, Cusack S. Class I tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase has a class II mode of cognate tRNA recognition. EMBO J. 2002;21:3829–3840. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38, 27–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eastwood MP, Hardin C, Luthey-Schulten Z, Wolynes PG. Evaluating protein structure-prediction schemes using energy landscape theory. IBM J. Res. Dev. 2001;45:475–497. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts E, Eargle J, Wright D, Luthey-Schulten Z. MultiSeq: unifying sequence and structure data for evolutionary analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:382. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang XL, Guo M, Kapoor M, Ewalt KL, Otero FJ, Skene RJ, McRee DE, Schimmel P. Functional and crystal structure analysis of active site adaptations of a potent anti-angiogenic human tRNA synthetase. Structure. 2007;15:793–805. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wakasugi K, Slike BM, Hood J, Otani A, Ewalt KL, Friedlander M, Cheresh DA, Schimmel P. A human aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase as a regulator of angiogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:173–177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012602099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fu X, Yu LJ, Mao-Teng L, Wei L, Wu C, Yun-Feng M. Evolution of structure in gamma-class carbonic anhydrase and structurally related proteins. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2008;47:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hendy MD, Penny D. A framework for the quantitative study of evolutionary trees. Systemativ. Zool. 1989;38:297–309. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bonnefond L, Giege R, Rudinger-Thirion J. Evolution of the tRNA(Tyr)/TyrRS aminoacylation systems. Biochimie. 2005;87:873–883. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salazar O, Sagredo B, Jedlicki E, Soll D, Weygand-Durasevic I, Orellana O. Thiobacillus ferrooxidans tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase functions in vivo in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1994;176:4409–4415. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.14.4409-4415.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Glaser P, Kunst F, Debarbouille M, Vertes A, Danchin A, Dedonder R. A gene encoding a tyrosine tRNA synthetase is located near sacS in Bacillus subtilis. DNA Seq. 1991;1:251–261. doi: 10.3109/10425179109020780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shiba K, Motegi H, Yoshida M, Noda T. Human asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase: molecular cloning and the inference of the evolutionary history of Asx-tRNA synthetase family. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5045–5051. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.22.5045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lamour V, Quevillon S, Diriong S, N'G;uyen VC, Lipinski M, Mirande M. Evolution of the Glx-tRNA synthetase family: the glutaminyl enzyme as a case of horizontal gene transfer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:8670–8674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gouet P, Courcelle E, Stuart DI, Metoz F. ESPript: analysis of multiple sequence alignments in PostScript. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:305–308. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]