Abstract

In this paper, we consider neighborhood selection as a social process central to the reproduction of racial inequality in neighborhood attainment. We formulate a multilevel model that decomposes multiple sources of stability and change in longitudinal trajectories of achieved neighborhood income among nearly 4,000 Chicago families followed for up to seven years wherever they moved in the United States. Even after we adjust for a comprehensive set of fixed and time-varying covariates, racial inequality in neighborhood attainment is replicated by movers and stayers alike. We also study the emergent consequences of mobility pathways for neighborhood-level structure. The temporal sorting by individuals of different racial and ethnic groups combines to yield a structural pattern of flows between neighborhoods that generates virtually nonoverlapping income distributions and little exchange between minority and white areas. Selection and racially shaped hierarchies are thus mutually constituted and account for an apparent equilibrium of neighborhood inequality.

The sorting of individuals by place is a fundamental concern to the burgeoning literature on neighborhood effects. Because individuals make choices and differentially allocate themselves nonrandomly, estimates of neighborhood effects on social outcomes—whether crime, mortality, teenage childbearing, employment, low birth weight, mental health, or children’s cognitive ability—may be confounded and thereby biased. By and large, the response to the potential of individual selection bias is to view it as interference, a statistical problem to be controlled away and not something of substantive interest in itself. The most common approach in the literature to date has been to estimate the effect of neighborhood poverty on some individual outcome by using a host of individual-level control variables.1

Yet selection is much more than a statistical nuisance when we consider its implications for inequality in neighborhood attainment and broader population-level processes. In this paper, we focus on a key aspect of selection—neighborhood sorting—by treating the neighborhood income attainment of an individual as problematic in its own right and thus requiring explanation. We specifically examine the sources and consequences of sorting for the reproduction of racial economic inequality in the lives of individuals and for the reproduction of a stratified urban landscape. Our data come from a recently completed study of white, black, and Latino families in Chicago followed no matter where they moved in the United States. Incorporating measures of human capital, time-varying life circumstances, and individual differences in factors typically hypothesized as unobserved sources of heterogeneity, such as depression, criminality, and social support, we model pathways of neighborhood attainment.

Our focus on life-course trajectories and consequent neighborhood change emphasizes that individuals make purposeful decisions about their environment, not only whether to stay put or move to a different neighborhood, but whether to leave their town or city altogether. These decisions are influenced by resources, preferences, and changing life circumstances, to be sure, but they are also conditioned by the interaction of an individual’s race/ethnicity with the wider structural context within which decisions are made. By simultaneously examining movers and stayers, we are able to separate the multiple sources of neighborhood change induced when an individual moves, when migration into or out of a community changes the context around an individual who nonetheless remains in place, and when secular changes in wider conditions occur, such as a city-level rise or decline in income. Choosing to remain in a changing or even declining neighborhood is a form of selection, after all, and can be just as consequential as the decision to relocate, an often overlooked point in debates about neighborhood effects.

The analytic goal of this paper may therefore be seen as twofold. At one level, it seeks to make headway on previously neglected sources of neighborhood stratification. Heckman (2005) recently articulated what he calls the “Scientific Model of Causality,” in which the goal is to confront directly and achieve a basic understanding of the social processes that select individuals into causal “treatments” of interest. Relying on randomization via the experimental paradigm, even if logistically possible, brackets knowledge of how causal mechanisms are constituted in a social world defined by the interplay of structure and purposeful choice. Although not a formal model in the Heckman (2005) sense, studying the predictors of sorting and selection into neighborhoods of varying types is an essential ingredient in the larger theoretical project of understanding neighborhood effects.

Secondly, the paper focuses attention on the social consequences of residential selection. Here, the question becomes how individual decisions combine to create spatial flows that define the ecological structure of inequality, an example of what Coleman (1990:10) more broadly argued is a major underanalyzed phenomenon—micro-to-macro relations. We translate this concern into an analysis of the structural flows of exchange between neighborhoods of different racial and economic status that appear to reproduce persistent racial inequality (Loury 2002).

TRAJECTORIES OF NEIGHBORHOOD ATTAINMENT

We approach the problem of neighborhood selection by modeling individual change in neighborhood environments as a multilevel process that unfolds over time. Building on what Alba and Logan (1993) referred to as the “locational attainment” model, a body of research has estimated the cross-sectional association between individual-level characteristics and census measures of neighborhood characteristics, usually the percentage of white (or black) neighbors and the poverty rate. This approach has been used to provide empirical evidence on differences between racial and ethnic groups in the extent to which individual resources and advantages are associated with desired neighborhood outcomes (Logan and Alba 1993; Logan et al. 1996). Models of urban demography put forth in early writings of the Chicago School (Park and Burgess 1925) assumed that members of minority or immigrant groups attempt to translate economic advances into residential advantage by moving out of segregated areas and into areas occupied by members of the dominant racial/ethnic group (Massey and Denton 1985).

Although differences in socioeconomic status explain a significant proportion of the discrepancies in neighborhood environments, a common finding is that substantial gaps between whites and nonwhites remain, even after multiple indicators of socioeconomic status are controlled for (e.g., Alba and Logan 1993; Logan and Alba 1993). That is to say, places are units of stratification in their own right, contrary to the Chicago School’s emphasis on unfettered sorting (or spatial assimilation) among “natural areas.” Thus, the demographic urban literature shifted to think not only of individual stratification and sorting but of place stratification (Logan 1978).

An important question remains, however, regarding the mechanisms by which place stratification is produced. If individuals are not followed over time, one cannot determine how individuals’ neighborhood environments change or how individual changes—for example, in life cycle or economic status—relate to neighborhood change (Massey and Denton 1985:97). To address this issue, a number of scholars have utilized longitudinal data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to assess how different groups of individuals move into or out of poor or segregated neighborhoods (see, e.g., Massey, Gross, and Shibuya 1994; South and Crowder 1997, 1998). This approach represents a step forward by taking a temporal perspective and considering a wider range of individual-level predictors, especially in the form of socioeconomic resources. The results show the continued persistence of racial/ethnic gaps in neighborhood income attainment among those who move (South, Crowder, and Chavez 2005), with blacks’ locational return on their social resources and human capital substantially less than whites, even after household wealth is accounted for (Crowder, South, and Chavez 2006).

A Multilevel Life-Course Strategy

In the present paper, we take the next step of decomposing and analyzing within-individual trajectories of neighborhood change by exploiting distinctive characteristics of the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN). As described in detail below, our data come from a stratified two-stage sample of approximately 5,600 children, ages 0 to 15 years and living in a representative sample of Chicago neighborhoods, who were intensively studied and followed wherever they moved, along with their caretakers, over a seven-year period. The PHDCN offers crucial analytic advantages for our theoretical interest in sorting and inequality.

First, the high levels of immigration into Chicago and its considerable ethnic diversity provide us with a sample that allows for detailed comparisons of whites, blacks, and Latinos, many of whom are recent immigrants, whereas others have lived in the United States for several generations. Second, by the end of the study follow-up, the neighborhoods of residence expanded to cover virtually all inhabitable neighborhoods in Chicago and a good chunk of the metropolitan area. Original sample members also migrated to a number of states around the country, notably Texas, California, New York, Florida, Mississippi, and Georgia. By following people wherever they went, we are able to decompose the elements of neighborhood change that arise from residential mobility (both within and outside of Chicago) from those occurring around stationary residents. These models of stability and change reflect the full distribution of realized neighborhood-level attainment over time in two key characteristics that will be used to describe racial inequality in neighborhood conditions: median income and segregation by race/ethnicity.

Third, the PHDCN allows us to go beyond research on neighborhood attainment that focuses on a fairly standard set of predictors based on socioeconomic background. There is strong reason to believe that some individuals end up in poor neighborhoods while others end up in more advantaged neighborhoods for reasons that go well beyond the canonical predictors of human capital and demography. The classic work of Faris and Dunham (1939), in particular, set the stage for the “drift” hypothesis, whereby individuals with vulnerabilities of mental state get stuck or drift into selected disadvantaged environments. At the opposite end, competence and social support systems have been hypothesized as important predictors of multiple facets of life-course advancement (Clausen 1991). The extensive data collection in the Chicago longitudinal study allows us to assess this general perspective by assessing covariates that, to our knowledge, have not been previously considered but represent potentially important dimensions of the ability or vulnerability of families in achieving residential outcomes. Elaborated below, we examine depression, family conflict, criminality, exposure to violence, and social support networks.

Drawing on the life-course conception of trajectory (Elder, Johnson, and Crosnoe 2003) and a human developmental focus on the importance of neighborhood selection over the life course (Settersten and Andersson 2002), we further emphasize the incorporation of time-varying circumstances to explain neighborhood attainment over the early life course of children and their families. To estimate the effects of within-individual change (e.g., in income) on change in neighborhood environments, we specify a hierarchical model whereby time points are nested within individuals. This specification enables us to decompose predictors of neighborhood attainment into between-individual (time-stable) and within-individual (time-varying) components. Essentially a fixed-effects analysis with the family serving as its own control, this strategy allows us to explicitly incorporate the effects of within-family change, providing information on how family transitions are transformed into residential advancement or decline.

The fact that multiple children were sampled within families means that we can also examine unique family effects within our general analytic multilevel framework. Specifically, our progression of models is constructed to allow us to decompose the overall variance in realized neighborhood conditions into variance resulting from change in neighborhoods occurring over the course of the survey, the variance due to changes in the neighborhoods of children from the same sampled household (induced, for instance, when one caretaker and child moves out), and the variance due to between-family differences in neighborhood conditions.

NEIGHBORHOOD TRANSITION FLOWS

The second major goal of this paper is to describe the social consequences of sorting or selection decisions for neighborhood racial inequality. With the notable exception of Quillian’s (1999) analysis of flows between different subtypes of neighborhoods, studies of change in individuals’ neighborhoods typically focus on individual processes and not on their aggregate consequences. We address this gap by observing the extent of interracial and interincome “exchange” between neighborhoods based on mobility transition matrices. The specific goal is to estimate neighborhood-level connections established by behavioral flows, which we define in terms of the proportion of a neighborhood’s residents that move or stay, by race and income.

There is, of course, a rich literature that uses simulations to estimate how neighborhood racial segregation is produced. Schelling’s (1971) is the classic statement on how individual preferences translate into a segregated residential structure. Through simulations of individual mobility behavior, he showed that collective sequences of mobility decisions made by individual actors responding to their divergent preferences for neighborhood composition can lead to a residential structure that is more segregated than any individual actor would prefer. However, Bruch and Mare (2006) showed that slightly different assumptions about how individuals respond to the presence of “out-group” neighbors lead to very different outcomes in the aggregate. Using data on neighborhood preferences, Bruch and Mare (2006) found that individuals’ probability of moving out of their neighborhood increases in a continuous manner as more and more members of the out-group enter the neighborhood. When these data on preferences are used as the basis for simulations of residential mobility patterns, small deviations from Schelling’s “tipping point” assumption lead to dramatically less segregation than Schelling’s simulations predict. The low levels of segregation produced by Bruch and Mare’s (2006) simulations raise the possibility that preferences, by themselves, cannot explain residential patterns in America.

The present study approaches neighborhood formation patterns from a complementary perspective that estimates how actual mover-stayer decisions bear on neighborhood income inequality. Instead of formal simulation models or data on stated preferences, we utilize the clustered nature of the initial sampling design to compare predictions of neighborhood income based on our multilevel mover-stayer model with observed variations in later neighborhood-level income. In other words, we integrate the knowledge gained from an analysis of families over time to inform our understanding of neighborhood-level distributions. Finally, and we believe most important, we exploit the community-level design to uncover the structural pattern of flows between and within neighborhoods by income status and racial composition.

DATA

Rather than conditioning on the poor, the first stage of the PHDCN research design started with the entire population of 343 Chicago neighborhood clusters defined by the aggregation of contiguous and socially similar census tracts (2.5 tracts and 8,000 residents on average), based on a wide array of demographic and ecological characteristics (Sampson, Raudenbush, and Earls 1997:919). To ensure a wide diversity of social contexts, the 343 neighborhood clusters were stratified by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status (SES), from which a random sample of 80 neighborhood clusters (NCs) was selected. In the second stage, dwelling units were enumerated within each of the 80 sampled NCs; in most cases, all dwelling units were listed, although in especially large NCs, census blocks were selected with probability proportional to size. Dwelling units were selected systematically from a random start within enumerated blocks. Over 40,000 households were screened to identify age-eligible participants. Household members eligible in age cohorts 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, or 18 were selected with certainty among randomly selected households. As a result, multiple siblings were interviewed within some households.

Subjects and caregivers in the PHDCN were interviewed or assessed in three waves, or time points of data collection. The project began in late 1994, but because of the large sample size and intensive interview schedule, the Wave 1 data were collected on a rolling basis and spaced out over roughly a three-year period. Follow-up interviews were conducted in a similar rolling way with a target of approximately 2–3 years between waves for individual subjects. The average date of the cohort interviews at each wave were late 1995, 1998, and 2001, with the period of data collection spanning 1994 to 2002. Personal interviews with children began when they reached the age of 9. Because of their unique status as adults, we exclude subjects in the 18-year-old cohort and focus on families with children from the 0-, 3-, 6-, 9-, 12-, and 15-year-old cohorts.2 The age of subjects in the sample ranges from 0 (less than 1 month old) at Wave 1 to a high of 22.1 years at Wave 3. Our final sample comprises 5,576 subjects within 3,863 families.

Although the original PHDCN multilevel design was clustered at baseline in the city of Chicago, the geographical dispersion of families over time was considerable. By the third wave of interviews, virtually all of Chicago was represented, plus a large swath of the metropolitan area stretching west, north into Wisconsin, and southeast to Indiana. Original sample members also migrated to a number of states around the country, notably Texas, California, New York, Florida, Mississippi, and Georgia. From the parent interviews, we geocoded detailed address information at all three waves of the survey, which we in turn linked to census tract codes across the United States, allowing us to map changes in the neighborhood residential locations of sample members occurring over the course of the survey. This information was then merged with demographic data on all census tracts in the United States from the Neighborhood Change Database (GeoLytics 2003) at both 1990 and 2000. We use linear interpolation to impute census tract information in the years between 1990 and 2000 and beyond. Like the tradition of research based on the PSID, we assume census tracts make reasonable proxies to assess the income status of neighborhoods. Using tracts over the PHDCN clusters (themselves defined through the aggregation of census tracts) also affords us greater statistical power at the macro level.

We deal with missing data in several steps. First, if individuals dropped out of the study, their information is excluded only in the wave(s) in which they did not take part in the survey. Second, we adjust for any bias that might arise due to attrition by modeling the probability that individuals will leave the survey at each wave and then weighting the data in the Level 1 (time-varying) file based on the inverse probability of attrition (further details available upon request). Third, for individuals who were interviewed in a given wave but who did not provide information for a specific variable, we use a multiple imputation procedure to impute missing values (Royston 2004). The method relies on the assumption that the data are missing at random, conditional on observed covariates in the imputation model (Allison 2001; Rubin 1987).

Our main neighborhood outcome is median income measured in year 2000 dollars. Although most studies of neighborhood stratification examine the low end of the distribution in the form of the poverty rate, we focus on median income because it better captures the full distribution of income in the neighborhood and yields a clearly interpretable measure of the economic status of neighborhood residents with a familiar metric: the dollar.

Baseline Status

We control for an extensive set of time-invariant family- and subject-level covariates, beginning with basic characteristics, such as the caregiver’s and subject’s age and sex. The caregiver’s race/ethnicity is coded with several indicator variables denoting whether the caregiver is white (the reference group in regression models), African American, Hispanic/Latino, or a member of another racial or ethnic group—Asian-Pacific Americans are the most common group among individuals in the “other” category. The caregiver’s immigrant generation is measured with three dummy variables indicating whether he/she is a first-generation immigrant (i.e., born outside the United States), second-generation (i.e., at least one birth parent was born outside the United States), or third-generation or higher—the reference group in regression models. We also include a citizenship variable (yes, no) indicating whether the caregiver is a U.S. citizen, and a measure of English language proficiency, which consists of dummy variables indicating whether the caregiver’s English language proficiency is good (the reference group), fair, or poor. The caregiver’s educational attainment is measured with four dummy variables indicating whether the caregiver has less than a high school diploma, a high school diploma or GED (the reference group in regression models), some college or professional school, or at least a college degree.

We measure five constructs that tap both the vulnerability and capacity of caretakers in neighborhood choice. On the vulnerability side, we include problems with the criminal justice system, violence, and mental health that are known to compromise life-course outcomes. Family criminality (Farrington et al. 2001) represents the number of family members with a criminal record. Domestic violence represents the sum of dichotomous responses to nine survey items asking caregivers about violent or abusive interactions with any current or previous domestic partner (Straus et al. 1996). This measure is based on the Revised Conflicts Scale (CTS2) and has a reliability of .84. Caregiver depression is a dichotomous measure based on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Short Form (Kessler and Mroczek 1997; Walters et al. n.d.), coded positively if the caregiver is classified as having experienced a period of major depression in the year prior to the interview. The reliability of the individual survey items used to generate the scale is .93. The same measure of maternal depression using the PHDCN has been shown by Xue et al. (2005) to be strongly predictive of child mental health problems, controlling for many other factors. Exposure to violence is measured by whether the caregiver (in the case of the 3-year-old and 6-year-old cohorts) or the subject (in the 9- through 15-year-old cohorts) saw someone shot or stabbed in the year prior to the interview (Bingenheimer, Brennan, and Earls 2005; Selner-O’Hagan et al. 1998). Such forms of violence are likely to influence how caregivers perceive the level of safety in their neighborhood, especially pertaining to children.

On the capacity side, we examine social support. Support from community members, including friends and family, has long been considered a means by which parents are able to collectively manage parenting tasks and maintain informal controls over youth (Furstenburg 1993; Sampson et al. 2002). Building on this idea, we conceptualize social support available to parents as a potentially important influence on the decision to relocate or remain in one’s community. The caregiver’s perceived level of social support is captured by the mean of 15 survey items (reliability = .77) on the degree to which the caregiver can rely on friends and family for help or emotional support and the degree of trust and respect between the caregiver and his/her family and friends (Turner, Frankel, and Levin 1983). Each of these five measures of vulnerability/capacity significantly predicts neighborhood attainment in bivariate analyses.

Time-Varying Covariates

We include a set of time-varying covariates that capture change in key aspects of individuals’ lives occurring over the course of the survey. The first group relates to employment and economic circumstances and includes the following measures: the employment status of the caregiver and the caregiver’s spouse or partner (working or not working); a dummy variable indicating whether the caregiver is receiving welfare; the caregiver’s total household income, consisting of six dummy variables indicating whether total household income is below $10,000, $10,000–$19,999, $20,000–$29,999, $30,000–$39,999 (the reference group in regression models), $40,000–$49,999, or $50,000 and above; and occupational status, based on the socioeconomic index (SEI) for caregivers (Nakao and Treas 1994). If the caregiver is not employed and has a partner, the partner’s SEI score is used. If both the caregiver and a partner are employed, the maximum score is used. We also include measures of homeownership, household size (the total number of individuals in the household), and the caregiver’s marital status, which consists of dummy variables indicating whether the caregiver is single (the reference group in regression models), cohabiting, or married.

All time-varying covariates refer to the subject or family’s status at the interview. To obtain detailed time-varying information between waves is, of course, desirable, but this was not possible across all the variables of interest within project constraints. Descriptive statistics on neighborhood outcomes and all covariates at the individual and family level are in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics: PHDCN Longitudinal Study

| Variable | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1: Time-Varying Outcome (N = 14,106 person-periods) | ||||

| Neighborhood median income, in 2000 dollars | 41,591 | 16,989 | 4,174 | 192,427 |

| Level 2: Individual (N = 5,576 children) | ||||

| Subject’s age | 6.8 | 5.0 | 0 | 17 |

| Subject’s gender, 1 = male | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Level 3: Family (N = 3,863 families) | ||||

| Caregiver race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0 | 1 |

| African American | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Other | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0 | 1 |

| Household income | ||||

| Below $10,000 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0 | 1 |

| $10,000–$19,999 | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0 | 1 |

| $20,000–$29,999 | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0 | 1 |

| $30,000–$39,999 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0 | 1 |

| $40,000–$49,999 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0 | 1 |

| $50,000 or more | 0.17 | 0.38 | 0 | 1 |

| Employment, caregiver, 1 = employed | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Employment, caregiver’s partner or spouse | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Occupational status (SEI) | 43.2 | 17.2 | 17 | 97 |

| Welfare receipt, 1 = receiving TANF | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 |

| Married | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Cohabiting | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0 | 1 |

| Homeownership, 1 = homeowner | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 |

| Total household size | 5.1 | 2.0 | 2 | 14 |

| Caregiver’s education | ||||

| Less than high school diploma | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| High school diploma/GED | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0 | 1 |

| Some college | 0.34 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 |

| College degree or more | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0 | 1 |

| Caregiver’s length of residence at current address | 5.44 | 6.48 | 0 | 59 |

| Caregiver’s age | 33.8 | 9.2 | 14 | 82 |

| Caregiver’s gender, 1 = male | 0.07 | 0.26 | 0 | 1 |

| Caregiver’s immigrant generation | ||||

| First generation | 0.38 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Second generation | 0.11 | 0.32 | 0 | 1 |

| Third generation or higher | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Citizenship, 1 = U.S. citizen | 0.71 | 0.45 | 0 | 1 |

| Caregiver’s English proficiency | ||||

| English is “good” | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 |

| English is “fair” | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0 | 1 |

| English is “poor” | 0.19 | 0.39 | 0 | 1 |

| Number of family members with a criminal record | 0.48 | 0.92 | 0 | 7 |

| Exposure to violence (caregiver and child) | 0.11 | 0.31 | 0 | 1 |

| Domestic violence | 2.1 | 2.7 | 0 | 11 |

| Social support | 2.6 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 3.0 |

| Caregiver depression, 1 = depressed | 0.21 | 0.40 | 0 | 1 |

| Neighborhood (N = 190 census tracts)a | ||||

| Percentage black, 1990 | 35.46 | 40.12 | 0.00 | 100.00 |

| Change in percentage black, 1990–1995 | 0.76 | 4.02 | –9.61 | 26.00 |

| Percentage Latino, 1990 | 29.55 | 31.29 | 0.00 | 97.91 |

| Change in percentage Latino, 1990–1995 | 1.23 | 6.52 | –19.25 | 25.60 |

| Log median income, 1990 | 10.46 | 0.53 | 8.79 | 11.85 |

| Change in log median income, 1990–95 | 0.07 | 0.18 | –0.76 | 0.70 |

Used in models predicting mobility out of Chicago (Table 4).

ANALYTIC STRATEGY

Model 1

In our first model, we estimate two parameters: one describing the subject’s neighborhood in the first survey wave, and the second describing change occurring over the course of the study. The second parameter in the model describes neighborhood change occurring from any source, whether individual mobility or change around an individual who does not move. Following the notation of Raudenbush and Bryk (2002:238–39), we describe Model 1 with five equations:

Level 1 Model:

| (1) |

Level 2 Models:

| (2) |

| (3) |

Level 3 Models:

| (4) |

| (5) |

Ytij represents the neighborhood median income for subject i in family j at time point t. In this model, time is set equal to 0 at Wave 1 of the survey, to 1 at Wave 2, and to 2 at Wave 3. The inclusion of this term allows for an estimate of the average linear change in neighborhood median income over the course of the survey; π0ij represents the initial neighborhood median income (at time = 0, or Wave 1 of the survey); π1ij represents the slope of change over the course of the survey; and etij is a within-subject (or over time) error term. The Level 2, or between-subject, model incorporates a subject-level random error term, r0ij, to the model predicting the initial neighborhood median income. Similarly, the Level 3, or between-family, model incorporates a family-level random error term, u00j. Model 1 thus provides a baseline description of the proportion of variance in neighborhood income that is between families, the proportion between siblings within families, and the proportion that is within individuals, or over time. This model also provides an estimate of the average neighborhood median income at Wave 1 of the survey, and the average change in median income over the full course of the study.3

Model 2

In the second model, we allow each of the parameters in the Level 1 model to vary by race and ethnicity. We thus expand the Level 3 (family-level) models to:

| (6) |

| (7) |

Whites serve as the reference group in these models, and other refers to all families who are not identified as white, African American, or Latino. In Eq. (6), the intercept γ000 represents the predicted neighborhood median income for whites, the reference group; γ001 is the gap between the initial neighborhood median income of blacks and whites; γ002 is the gap between Latinos and whites; and γ003 is the gap between others and whites. In Eq. (7), γ010 represents the predicted linear change in neighborhood median income for whites, γ011 is the difference in the slope of change among blacks and whites, γ012 is the difference in the slope of change among Latinos and whites, and γ013 is the difference between all others and whites. By comparing the Level 3 variance component from Model 2 with that from Model 1, we can estimate the proportion of between-family variance that is explained by race/ethnicity.

Model 3

In the third model, we incorporate residential mobility into the analysis of change in neighborhood conditions in the Level 1 (time) equations:

| (8) |

In this model, move is a dichotomous indicator of whether the subject lived at an address different from the original address, and move out of Chicago is a dichotomous indicator of whether the subject lived at a new address outside of Chicago. By interacting these indicators with the measure of change over time (time), it is possible to estimate the initial differences and the change in neighborhood median income for individuals in the survey who remain at their original addresses, those who move within the city, and those who move out of Chicago.

It is important for the present study that the slopes of change in our core models are reliably estimated. The reliability of the slope of change in median income for stayers in the neighborhood is .59; for movers out of the city, it is .84; and for movers within the city, it is .75.4 These results indicate that there is substantial “signal” in our data in terms of individual differences in the rate of change in neighborhood income over the course of the study period, and thus that modeling of these parameters is warranted (see Raudenbush and Bryk 2002: chap. 6).

There are now six terms in the Level 1 model representing the initial status and change for stayers, for movers within the city, and for movers outside of the city. In the Level 3 models, we allow each of these terms, π0ij through π5ij, to vary by race and ethnicity. All these models have the same basic form as Eqs. (6) and (7). The coefficients in Model 3 take on slightly different interpretations. At Level 1, π0ij, the overall intercept, represents the initial neighborhood median income for individuals who do not move (stayers); π1ij is the linear change in neighborhood median income for stayers; π2ij now represents the difference between the initial neighborhood median income among stayers and among those who move within Chicago; π3ij represents the difference between stayers and movers within Chicago in the slope of linear change; π4ij now represents the difference between the initial neighborhood median income among those who move outside of Chicago as compared with those who move within the city; and π5ij represents the difference in the slope of change between movers outside the city and movers within the city. Because we allow each of these terms to vary by race and ethnicity, the coefficients in the Level 3 models take on the same basic meanings as in Eqs. (6) and (7). The intercepts represent the predicted status for whites, the reference group, and the coefficients are used to estimate the gap between members of the given racial or ethnic group and whites.

Model 4

The final model in the progression incorporates an extensive set of fixed and time-varying covariates. Most of these covariates are at the family level, although we also include the subject’s age and gender in the Level 2 model as subject-level covariates.5 By including the mean value for each time-varying covariate over the three survey waves in the Level 3 model, as well as the deviation from this mean in the Level 1 model, we simultaneously estimate the effects of the average status and within-individual change in each of the covariates occurring over the three survey waves, controlling for secular change.6 This model progression permits us to assess whether racial and ethnic differences in neighborhood change obtained in Models 1 through 3 are attributable to correlated time-varying or fixed characteristics.

RESULTS

We begin with an unconditional model that estimates average trajectories of neighborhood median income for the entire sample (Table 2, Model 1). Results are weighted to account for potential attrition bias. We do not employ sample weights because they artificially inflate the household-level variance; design-weighted results were nonetheless similar. About 74% of the variation is between families, and almost 26% is due to changes in the same families’ neighborhood environments over time. Less than 1% of the variance is due to differences in the neighborhood environments of siblings who began the study living in the same household.

Table 2.

Models of Initial Status and Change in Neighborhood Median Income: PHDCN Longitudinal Study

| Model 1 Unconditional Model | Model 2 Race and Ethnicity | Model 3 Unadjusted Trajectoriesa | Model 4 Adjusted Trajectoriesa,b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Status |

Initial Status |

Initial Status, Stayers |

Initial Status, Stayers |

|

| Intercept | 40,204** (253) | 54,556** (745) | 54,111** (951) | 49,112** (1,594) |

| Black | –17,711** (840) | –17,074** (1,094) | –10,554** (975) | |

| Latino | –18,168** (788) | –18,124** (1,015) | –8,921** (1,022) | |

| Other Race | –12,106** (1,320) | –11,265** (1,581) | –6,458** (1,444) | |

| Change Over Time |

Change Over Time |

Change, Stayers |

Change, Stayers |

|

| Intercept | 2,477** (140) | 3,366** (383) | 1,402** (229) | 1,257** (228) |

| Black | –1,533** (455) | –605* (295) | –586* (290) | |

| Latino | –777 (428) | –338 (278) | –392 (276) | |

| Other Race | –772 (765) | –955* (463) | –1,058* (464) | |

| Change, Movers Within Chicago |

Change, Movers Within Chicago |

|||

| Intercept | 1,506 (848) | 1,639 (841) | ||

| Black | –104 (961) | –164 (953) | ||

| Latino | 1,347 (908) | 1,170 (902) | ||

| Other Race | –848 (1,324) | –828 (1,321) | ||

| Change, Movers Outside Chicago |

Change, Movers Outside Chicago |

|||

| Intercept | 6,270** (1,248) | 5,998** (1,249) | ||

| Black | –1,528 (1,532) | –1,331 (1,522) | ||

| Latino | –1,522 (1,409) | –1,397 (1,405) | ||

| Other Race | 4,458 (2,540) | 4,731 (2,571) | ||

| Percentage of Variance | Percentage of Variance Explainedc | Percentage of Variance Explainedc | Percentage of Variance Explainedc | |

| Level 1 | 26 | 0 | 10 | 10 |

| Level 2 | < 1 | 0 | 13 | 13 |

| Level 3 | 74 | 25 | 26 | 41 |

Models 3 and 4 also include dummy variables representing variation in the initial conditions of movers within and outside the city; the coefficients from these dummy variables are not shown in the table.

Model 4 includes the full set of covariates; the coefficients for all nonrace predictors are shown in Table 3.

Percentage of the variance at the given level from Model 1 that is accounted for in the current model.

Significant at p ≤ .05;

Significant at p ≤ .01.

In Model 2, we let the parameters representing initial status and change in median income vary by race and ethnicity, with whites as the reference group. The data show that African Americans in Chicago live in neighborhoods with median incomes about $17,700 lower than whites, while the gap between whites and Latinos is more than $18,000. Members of other racial and ethnic groups live in neighborhoods with median incomes that are about $12,000 lower than whites. This model reveals a racial and ethnic hierarchy of neighborhoods that is large in magnitude; whereas whites are estimated to live in neighborhoods with a median income over $54,000, blacks and Latinos live in neighborhoods where the median income is roughly a third lower. Including race and ethnicity in the model without other predictors explains about a quarter of the between-family variance in neighborhood income.

Over the course of the survey, the gaps between whites and nonwhites grow slightly, though all groups experience a positive slope of change. The neighborhood median income of whites rises by almost $3,400 at each wave of the survey ($6,800 from Wave 1 to Wave 3). The gap between the slope of change for whites and blacks is about $1,500 per wave, meaning the net slope of change for blacks is about $1,800 per wave. For Latinos and all others, the net slope of change is about $2,600 per wave. In Model 3, we begin to decompose the sources of within-individual change in neighborhood conditions by distinguishing between change in residential environments that is attributable to residential mobility and change occurring around stayers. We do so by adding indicators for residential mobility, within and outside the city, to the Level 1 model, explaining about 10% of the Level 1 (within-individual) variance. All of the parameters in the Level 1 model are allowed to vary by race and ethnicity in Model 3, enabling us to estimate the return to residential mobility for each group.

The first set of coefficients in Model 3 (Table 2) shows the same large gaps in the initial neighborhood conditions of whites and nonwhites that are present in Model 2. Because this model incorporates mobility into the analysis, we focus primary attention on change in neighborhood conditions. The second set of coefficients describes Chicago residents who remain at their original addresses throughout the course of the survey (stayers). Among white stayers, we find a slight positive trend in neighborhood median income of about $1,400 per survey wave. For both blacks and all others, the positive time trend is slightly less steep, meaning that the gaps between white stayers and both black and all other stayers rise slightly over the survey. The significant trajectories of change found among all groups of stayers highlights the fact that neighborhood change occurs even among those who do not move.

The third set of coefficients shows that movers within the city experience larger gains in neighborhood median income than stayers of the same race or ethnicity, with the largest returns to mobility occurring among Latinos. The slope of change for whites who move within Chicago is about $1,500 per wave greater than the slope for white stayers. By adding the coefficient describing the change in neighborhood median income for white movers within Chicago with that from white stayers, we estimate that white movers within the city experience an increase of about $2,900 per survey wave, or $5,800 from Wave 1 to Wave 3. The difference in the slopes of change for African Americans who move within the city as compared with those who remain at their original addresses is similar to that for whites, while Latinos who relocate within Chicago experience a steeper gain of about $3,900 in neighborhood median income at each survey wave, or $7,800 from Wave 1 to Wave 3. Overall, residential moves within the city appear to lead to substantial improvement in neighborhood income for all groups of movers.

The fourth set of coefficients in Model 3 shows that the largest changes in neighborhood environment occur among movers who leave the city. The difference in the slope of change for white movers who leave the city as compared with those who remain in Chicago is almost $6,300 per survey wave. Combining coefficients, we estimate that whites who leave Chicago enter neighborhoods with median incomes close to $9,200 higher than their neighborhoods of origin. Over the course of the survey, the total change for white movers who exit the city is a substantial $18,400. The difference in the slopes of change for African Americans and Latinos who leave the city as compared with those who relocate within Chicago are not quite as high as that for whites, but they are similar. The total gain in neighborhood median income for African Americans who exit Chicago is $13,900 from Wave 1 to Wave 3; for Latinos, the gain is about $17,300. The returns to leaving Chicago are even larger for members of other racial and ethnic groups, who experience a gain of almost $23,700 from Wave 1 to Wave 3.

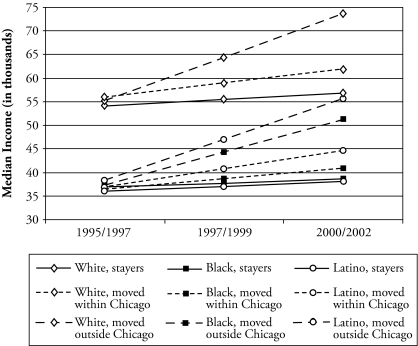

Results from Model 3 are more clearly interpretable when graphed. Figure 1 displays estimated trajectories of neighborhood median income for stayers, movers within the city, and movers who leave the city. (For parsimony, we exclude the small number of individuals not identified as white, black, or Latino.) The dramatic racial and ethnic inequality in neighborhood conditions that characterizes residential Chicago is immediately apparent— the trend lines describing trajectories of neighborhood attainment for whites all begin at a much higher point in the graph than those for blacks and Latinos, and all groups of whites continue to live in relatively advantaged neighborhoods throughout the study. Note that initial neighborhood conditions of the eventual movers and stayers, within racial/ethnic groups, are nearly identical, suggesting that selection into initial differences in context cannot explain the temporal pattern.

Figure 1.

Unadjusted Trajectories of Neighborhood Median Income, by Mover-Stayer Status in Chicago and Race/Ethnicity: PHDCN Longitudinal Study

The second striking feature in Figure 1 is the improvement in neighborhood conditions attributable to residential mobility; this is especially apparent among movers who leave Chicago. Though all trend lines describe positive secular change in neighborhood median income, the dashed lines tracking those who exit Chicago make clear that leaving the city is associated with enormous gains in neighborhood affluence. These improvements are visible for each racial and ethnic group. A third feature of the graph in Figure 1 is the apparent reproduction of racial inequality that occurs among all groups of movers and stayers, including those who exit the city. Put differently, initial results indicate that selection reinforces hierarchy, such that among each group of movers and stayers, we find the same racial stratification of place.

Multivariate Predictors of Status and Change

One possible explanation for the persistence of racial inequality among each group of movers and stayers is racial and ethnic heterogeneity in economic status, life-cycle stage, or other potential factors that might influence residential choices. Model 4 in Table 2 addresses this possibility by adjusting for an extensive set of covariates. We include both stable characteristics of individuals and families as well as time-varying covariates that measure the relationship between changes in individuals’ lives and changes in their neighborhood context.

In Table 3, we display all multivariate coefficients from this model in the form of dollar values for individual and family-level covariates other than race. Consistent with the spatial assimilation model, household income and education are strong predictors of neighborhood income. Compared with high school graduates, caregivers with at least a college degree are estimated to live in neighborhoods where the median income is roughly $2,500 higher. Compared with families with total household income in the range of $30,000–$39,999 per year, being in the highest income group (household income over $50,000) is associated with a jump in neighborhood median income of about $7,400. By contrast, being in the lowest income group (less than $10,000) is associated with a drop in neighborhood median income of $2,500 relative to the reference group. While average income has a positive association with neighborhood median income, change in household income leads to improvement in the neighborhood environment; specifically, individuals who enter the highest income group during the course of the survey seem to shift their residences accordingly, moving into more affluent neighborhoods.

Table 3.

Fixed and Time-Varying Predictors of Neighborhood Median Income: PHDCN Longitudinal Study

| Covariates | Average Statusa | Individual Changeb | Effect of Wave 1 Statusc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-Varying Covariates | |||

| Income (reference group: $30,000–$39,999) | |||

| Below $10,000 | –2,455* | –445 | |

| $10,000–$19,999 | –1,418 | –714 | |

| $20,000–$29,999 | –732 | –719* | |

| $40,000–$49,999 | 767 | –267 | |

| $50,000 or more | 7,370** | 778 | |

| Employment/welfare | |||

| Caregiver’s partner/spouse works | –263 | –92 | |

| Caregiver works | –325 | 96 | |

| Occupational prestige (max of caregiver/partner) | 91** | 9 | |

| On welfare | –745 | –311 | |

| Marital status (reference group: single) | |||

| Married | –2,036* | 175 | |

| Cohabiting | –2,071* | –91 | |

| Homeowner | 5,927** | 1,537** | |

| Household size | –175 | 349** | |

| Fixed Covariates | |||

| Education (reference group: high school graduate) | |||

| Caregiver has less than high school diploma | –1,000 | ||

| Caregiver has some college | –160 | ||

| Caregiver has college degree or more | 2,524* | ||

| Length of residence at current address | –49 | ||

| Age/gender | |||

| Subject’s age | –15 | ||

| Caregiver’s age | 1 | ||

| Caregiver is male | –251 | ||

| Subject is male | –33 | ||

| Caregiver’s immigrant generation (reference group: third or higher generation) | |||

| First generation | −2,110* | ||

| Second generation | –961 | ||

| Caregiver is a U.S. citizen | –1,406* | ||

| Caregiver’s language proficiency (reference group: English is “good”) | |||

| English is “fair” | –519 | ||

| English is “poor” | –481 | ||

| Family crime/domestic violence/exposure to violence | |||

| Number of family members with criminal record | –531* | ||

| Exposure to violence (caregiver and child) | –1,485** | ||

| Domestic violence | 5 | ||

| Social support | 1,612* | ||

| Caregiver has depression | 235 |

Note: Race/ethnicity coefficients are shown in Table 2.

The coefficients in the “average status” column represent the effect of the given covariate at its average level for the individual over the course of the survey.

The coefficients in the “individual change” column represent the effect of deviation from the individuals’ average status; in other words, the effect of within-individual change.

The set of coefficients for all fixed covariates represent the effect of the given covariate at its Wave 1 level; see description of Table 2, Model 4 in the text.

Significant at p ≤ .05.

Significant at p ≤ .01.

Education and income are not all that matters. Homeownership is independently associated with an average level of neighborhood median income that is roughly $5,900 higher than non-homeowners, while buying a home during the course of the survey is associated with an improvement in neighborhood median income of almost $1,500. Not surprisingly, first-generation compared with third-generation immigrants exhibit lower levels of neighborhood income (over $2,100 less). Noncitizens also fare less well. Families that grow larger during the course of the survey (e.g., through the birth of a child, marriage) appear to adjust their residential location by entering higher-income neighborhoods (approximately a $300 gain for each additional person). Overall, these patterns are consistent with both the human capital and life-cycle approaches.

One unexpected finding is that marriage and cohabitation are associated with a reduction in neighborhood income relative to being single. We explored this result in more depth to understand the mechanism behind this pattern. When we introduce only the measures of average marital status and change in marital status to the model in Table 3, excluding all other covariates, being married is associated with a substantial ($4,200) improvement in neighborhood income, while cohabiting is associated with a reduction of roughly $1,500. The positive coefficient attached to the indicator for marriage switches sign, however, when we include measures of household income in the model. Thus, the benefits of marriage appear to be entirely attributable to having higher household income, which is not altogether surprising. Note, moreover, that becoming married between waves of the survey is associated with a slight improvement (albeit not significant) in neighborhood income.

Table 3 also includes several measures designed to capture family aspects typically not measured in analyses of neighborhood mobility. Families with members who have criminal records are likely to live in lower-income neighborhoods (–$500 for each additional family member with a criminal record), and exposure to violence is associated with living in neighborhoods with median incomes roughly $1,500 lower than those of families who did not report exposure to violence. By contrast, caregivers who report having high social support from friends and family live in neighborhoods that are estimated to be about $1,600 more affluent. Neither depression nor domestic violence is directly associated with neighborhood income.

Despite these interesting associations, however, including the full set of covariates does not change the basic unadjusted patterns displayed in Figure 1. Moreover, whereas the full model explains about 41% of the between-family variation (compared with 25% in Model 3), the model continues to explain only 10% of within-person variation. This result suggests that the inclusion of time-varying covariates measuring change in household income, employment, occupation, education, and household size does not help to account for the remaining variation in individuals’ neighborhoods over time.

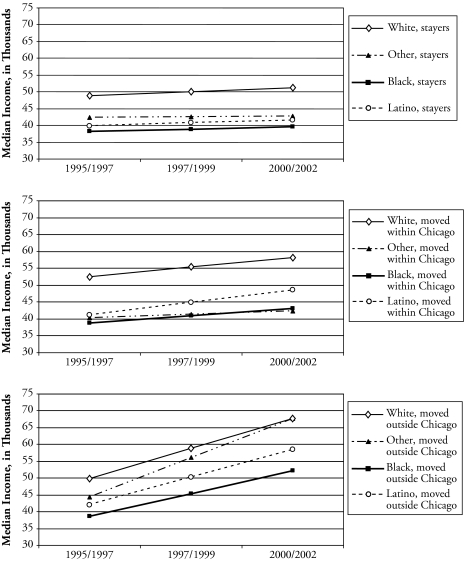

To see these patterns more clearly, Figure 2 shows the analogous trajectories of neighborhood change for movers (in Chicago and outside Chicago) and stayers adjusted for the full set of covariates. The size of the racial and ethnic gaps in neighborhood income is reduced in these models, suggesting that the superior economic position of whites in the sample explains at least a portion of the racial inequality in neighborhood conditions. Slopes of change also differ somewhat from those in Model 3, revealing that change in individuals’ environments that arise from residential mobility can be partially accounted for by heterogeneity among movers and stayers. These slight differences are far outweighed, however, by the striking similarity of patterns between Figures 1 and 2. The bottom-line result is that most of the racial and ethnic inequality in neighborhood attainment cannot be explained by changing economic circumstances, life-cycle stage, or other major characteristics of families that might influence residential decisions. After accounting for these and other factors heretofore not considered in the mobility literature, we continue to find that whites attain neighborhoods that are substantially more affluent than nonwhites, and that residential mobility leads to sharp improvements in neighborhood income, especially among those leaving Chicago.7

Figure 2.

Covariate-Adjusted Trajectories of Neighborhood Median Income, by Mover-Stayer Status in Chicago and Race/Ethnicity: PHDCN Longitudinal Study

MOVING OUT (AND UP)

Our findings thus far motivate an additional question: what predicts who leaves the city and who does not? Updating and extending the demographic literature on neighborhoods and residential mobility (see, e.g., Crowder 2000; Lee, Oropesa, and Kanan 1994; Rossi 1980), we address this situation in Table 4 by displaying the results from models of mobility outside Chicago for the overall sample and then for whites, African Americans, and Latinos separately. We employ the same individual- and family-level covariates as before, but now introduce neighborhood covariates that measure both the initial status and change in the racial and economic composition of neighborhoods during the first half of the 1990s (i.e., up to the first survey wave).

Table 4.

Predictors of Mobility Outside Chicago, by Race/Ethnicity: PHDCN Longitudinal Study

| Covariates | All | Whites | African Americans | Latinos |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighborhood-Level Covariates | ||||

| Percentage black, 1990 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.01* |

| Change in percentage black, 1990–1995 | 1.02** | 1.06** | 1.00 | 1.05* |

| Percentage Latino, 1990 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Change in percentage Latino, 1990–1995 | 1.02* | 1.03 | 0.96 | 1.04** |

| Log median income, 1990 | 1.16 | 1.19 | 1.11 | 1.04 |

| Change in log median income, 1990–1995 | 0.78 | 0.68 | 0.53 | 2.20 |

| Race/Ethnicity (reference group: whites) | ||||

| African American | 0.39** | ––a | ––a | ––a |

| Latino | 0.38** | ––a | ––a | ––a |

| Other | 0.59** | ––a | ––a | ––a |

| Subject- and Family-Level Covariates | ||||

| Income (reference group: $30,000–$39999) | ||||

| Below $10,000 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.56* | 1.25 |

| $10,000–$19,999 | 0.96 | 0.51 | 0.66 | 1.45 |

| $20,000–$29,999 | 0.94 | 0.67 | 0.57* | 1.43 |

| $40,000–$49,999 | 1.11 | 0.79 | 1.19 | 1.12 |

| $50,000 or more | 0.90 | 0.70 | 0.88 | 1.18 |

| Employment/welfare | ||||

| Caregiver’s partner/spouse employed | 0.99 | 0.56 | 1.78* | 0.66 |

| Caregiver employed | 1.07 | 1.46 | 1.05 | 0.92 |

| Occupational status (max of caregiver/partner) | 1.01* | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02** |

| On welfare | 0.79* | 0.82 | 0.88 | 0.71* |

| Marital status (reference group: single) | ||||

| Married | 0.98 | 1.43 | 0.61 | 1.49 |

| Cohabiting | 0.74* | 0.54 | 0.54** | 1.09 |

| Homeowner | 0.75* | 0.46** | 0.73 | 0.90 |

| Household size | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.97 | 1.03 |

| Education (reference group: high school graduate) | ||||

| Caregiver has less than high school diploma | 0.78 | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0.94 |

| Caregiver has some college | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.04 |

| Caregiver has college degree or more | 1.02 | 1.54 | 0.75 | 0.80 |

| Length of residence at current address | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| Age/Gender | ||||

| Subject’s age | 0.97** | 0.95 | 0.97* | 0.98 |

| Caregiver’s age | 0.98** | 0.96** | 1.00 | 0.96** |

| Caregiver is male | 0.83 | 0.51** | 1.10 | 0.54** |

| Subject is male | 1.01 | 0.92 | 0.90 | 1.16 |

| Caregiver’s immigrant generation (reference group: third or higher generation) | ||||

| First generation | 1.68** | 1.46 | 0.97 | 1.67 |

| Second generation | 1.28 | 0.78 | 2.05 | 1.06 |

| Caregiver is a U.S. citizen | 1.14 | 1.47 | 0.29** | 1.41* |

| Caregiver’s language proficiency (reference group: English is “good”) | ||||

| English is “fair” | 0.90 | 1.37 | 2.88 | ––b |

| English is “poor” | 1.12 | 1.48 | 0.36 | ––b |

| Family crime/domestic violence/exposure to violence | ||||

| Number of family members with criminal record | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.02 | 1.00 |

| Exposure to violence (caregiver and child) | 1.15 | 1.97 | 1.38* | 0.93 |

| Domestic violence | 1.01 | 1.04 | 1.02 | 1.00 |

| Social support | 1.02 | 0.81 | 1.17 | 0.96 |

| Caregiver depression | 1.14 | 1.68* | 0.99 | 1.03 |

Notes: Figures represent odds ratios. Standard errors are not shown.

Not applicable.

Not estimable (measures excluded due to multicollinearity).

Significant at p ≤ .05.

Significant at p ≤ .01.

We begin with Model 1 in Table 4 for the pooled sample. Note, first, that all groups of nonwhites are less likely to move out of Chicago than whites. Second, families who leave the city appear to be responding to changes in neighborhood racial and ethnic composition. Although the prevalence of nonwhite residents in 1990 does not have an independent influence on future mobility patterns, changes in racial composition occurring in the years prior to the cohort study—specifically, increases in the percentage of black and Latino neighbors from 1990 to 1995—make it more likely overall that families exit the city (cf. Crowder 2000). Third, however, the statistically significant and large influence of an increase in the percentage of black residents on moving out is restricted to whites and Latinos. Blacks, by contrast, do not respond to changes in the size of the black (or Latino) populations, suggesting that the racial composition of the neighborhood may be less important to them than to other groups. This interpretation is consistent with research showing that blacks are the group most willing to live in integrated neighborhoods (Charles 2000).

Few individual- or family-level factors have consistent associations with mobility across the three racial and ethnic groups. In the pooled sample and among Latinos, we find that high occupational status is associated with mobility out of the city, but in general, the various measures of socioeconomic status (notably income and education) have a weaker influence than one might have predicted. Among the factors that predict mobility with some consistency are homeownership and age: homeowners and older caregivers are less likely to move outside Chicago, as are the families of older children in the sample. We also find that caregivers who cohabit are less likely to exit Chicago, while first-generation immigrants are more likely to leave the city. Interestingly, African American caregivers who report exposure to serious forms of violence are more likely to leave the city (the coefficient is also positive for whites, although not significant due to the small sample). White caregivers who report a period of major depression are also more likely to exit Chicago, providing additional evidence that noneconomic factors may be important for understanding decisions regarding residential location.

In short, any neighborhood economic benefits that arise from suburban moves are most commonly experienced by whites. To a surprising extent, however, mobility is not influenced by individual or family characteristics but rather by changes in the neighborhood of origin—whites and Latinos are more likely to exit the city if they live in neighborhoods where blacks and Latinos have a growing presence. Although indirect, this evidence is highly suggestive of a “white and Latino flight” response that serves as another mechanism underlying racial hierarchy. Considering the consistent finding that Latinos are similar to whites in their desire to live in neighborhoods with few African Americans (Charles 2001), it is surprising that the significance of Latino flight (see also Fairlie 2002) has not received more attention in the literature on persistent residential segregation. In conjunction with the rapidly changing nature of U.S. society in terms of Latino immigration, our results suggest that this topic is ripe for further inquiry.

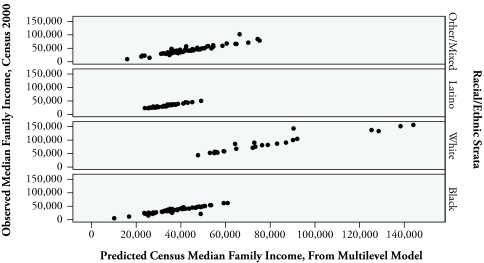

FROM INDIVIDUAL ACTIONS TO NEIGHBORHOOD FLOWS

An implication of our analysis is that the causes of residential moves may prove to be less important than their aggregate consequences for the reproduction of a racialized hierarchy of place at the structural level. We pursue this line of inquiry in two ways by responding, at least in preliminary form, to Coleman’s (1990:10) call for the study of “type 3” micro-macro relations. In the first approach, we use coefficients from the full multilevel model in Table 3 of the locational attainment process to generate predicted values of neighborhood median income at Wave 3 for each subject. We exploit the stratified design of the PHDCN by focusing on the original sample of 80 neighborhood clusters, consisting of 190 census tracts, within which a representative sample of children was drawn. At Wave 3, these original neighborhoods contain both original stayers and in-movers and, because of the clustered design, produce a sufficient sample size to aggregate the predicted values and obtain reliable between-neighborhood estimates (Raudenbush and Sampson 1999). For purposes of this analysis, we classify neighborhoods by race/ethnicity—those at least two-thirds white (N = 26), black (N = 56), and Latino (N = 36). The fourth category includes all other racially mixed neighborhoods (N = 72).

Based on this design, we first estimate a two-level hierarchical model that examines the variability of predicted individual values of neighborhood income attainment within and across the 190 tracts. In this model, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of predicted median income at the neighborhood level is .92, and the aggregate reliability is .99, confirming the strong between-neighborhood variability. In addition, within each set of neighborhood types defined by race/ethnicity, the correspondence between predicted and observed median income is almost exact, although as shown in Figure 3, there is virtually no overlap in the distributions of neighborhood median income for black and white areas. It is only for neighborhoods of about $50,000 median income that we find an overlap, and yet this is the low end for white neighborhoods and the high end for black neighborhoods. These results confirm that our multilevel process model closely predicts neighborhood-level attainment outcomes and reaffirms the fundamental racial income inequality at the neighborhood level.

Figure 3.

From Individual Actions to Neighborhood Structure: Observed Median Income (U.S. Census) at Wave 3 and Predicted Median Income From PHDCN Multilevel Longitudinal Mobility Model: 190 Chicago Census Tracts, by Racial/Ethnic Strata

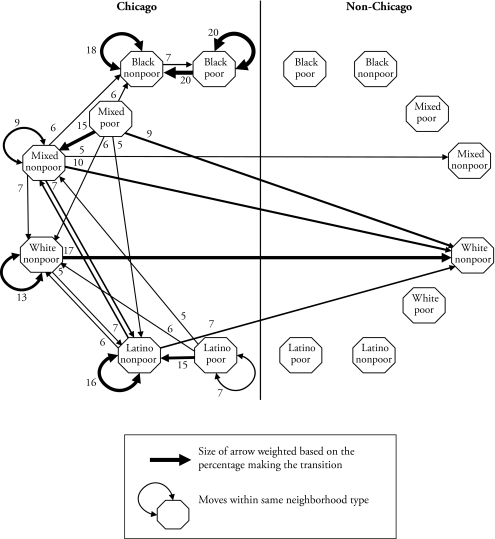

Figure 4 pushes the analysis one step further by exploring the structural pattern of flows connecting origin neighborhoods in Chicago to destinations anywhere in the United States. Drawing on findings to this point, we classify neighborhoods based on location within or outside Chicago (mostly suburban Chicago), the dominant neighborhood racial/ethnic group or mix as defined above, and poverty status; neighborhoods with median income in the bottom quartile of Chicago’s distribution are defined as poor. Our graphs depict transitions across neighborhoods undertaken by at least 5% of the residents in each origin neighborhood.8 Consistent with our decomposition of change approach, we also graph stayer mobility pathways if at least five percent of residents moved addresses but remained in the given neighborhood subtype over the course of the survey. By focusing on the most prominent transitions, the analysis is designed to complement our analysis of individual trajectories by showing how aggregate movement connects neighborhoods and thereby produces a linked network of stratification.9

Figure 4.

Structural Pattern of Neighborhood Mobility Flows: Mover-Stayer Pathways of Exchange Among White, Black, Latino, and Mixed Neighborhoods, by Poverty and Chicago Location

Notes: All flows represent the percentage of families in the origin neighborhood making a transition, either within (moverstayers) or to another neighborhood type. Arrows are not shown for transitions under 5% (see the text). Numbers attached to arrows indicate the percentage of individuals making the transition.

The pattern of flows in Figure 4 renders visible the structural consequences of the findings that have been presented throughout the analysis. Note, first, that only tiny flows of Chicago residents produce upward mobility in the sense of crossing the boundaries of the racial and ethnic hierarchy that is present in Chicago neighborhoods and well beyond. By far the most common outcome is to stay at one’s original address, a crucial ingredient in reproducing the system of place stratification. Moreover, the next most common transition leads movers into neighborhoods of the same subtype. Circulation within African American neighborhoods is especially common, as seen in the 20% of families in segregated, poor black neighborhoods who change addresses but remain in the “ghetto”; similarly, 18% of residents in black nonpoor neighborhoods move into different neighborhoods of the same type. Twenty percent of families in black poor neighborhoods do leave, but to other segregated black areas (cf. Wilson 1987). The largest pathway that crosses the black-white divide is from black middle-class areas to white nonpoor areas outside Chicago, and yet this transition is negligible, representing less than 5% of residents in such origin neighborhoods.

The dominant flows crossing a racial or ethnic boundary serve to reinforce the hierarchy of neighborhoods rather than undermine it. Extending earlier results, Figure 4 shows that (a) four out of the five dominant pathways out of Chicago are to white nonpoor areas, (b) white-origin neighborhoods (all of which are nonpoor) generate the largest pathway out of Chicago, and (c) white neighborhoods in Chicago are a favored destination but do not send to any neighborhood subtype other than Latino nonpoor (5% make this transition). Yet by repeating the analysis using transition rates calculated for members of each racial/ethnic group (cf. Quillian 1999), we find that this flow consists almost entirely of Latinos moving from predominantly white origin areas into Latino neighborhoods (results from race- and ethnicity-specific flows available upon request). Race-specific flows also document that 80% of whites transition into (or remain in) neighborhoods that are predominantly white and nonpoor, whether inside or outside the city. By contrast, when blacks and Latinos leave Chicago, they continue to live in areas that are markedly less affluent than their white counterparts—for instance, on average, the neighborhood median income for blacks who leave the city is 30% less than for whites who leave the city (see Figure 1). Considering the improvements in neighborhood quality associated with mobility outside the city, this pattern thus reveals one of the major ways in which whites maintain an ongoing advantaged position in the hierarchy of neighborhoods, even in a multiethnic and economically diverse area such as Chicago.

Figure 4 further reveals a largely underappreciated pattern of flows among racially hetero geneous areas. There is considerable neighborhood “exchange” that involves Latino and mixed areas, and to a lesser extent, Latino and white areas. For example, we see a reciprocal exchange between Latino and mixed (heterogeneous) nonpoor neighborhoods, and between white nonpoor and Latino nonpoor neighborhoods, although the exit pathway from white nonpoor neighborhoods to outside Chicago suggests that Latinos are moving into white Chicago neighborhoods in the throes of transition and hence on their way toward becoming Latino enclaves. At the same time, we find that the pathway connecting Latino nonpoor neighborhoods to white nonpoor neighborhoods outside Chicago comprises primarily Latinos, indicating that nontrivial numbers of Latinos are moving into suburban neighborhoods that are primarily white. The larger point is that family mobility forms connections between white and Latino areas only, not black. Figure 4 thus confirms a stark reality: the sheer lack of significant pathways to any poor neighborhoods outside Chicago and to any black or Latino neighborhoods constitutes a hierarchy of racial and economic residential exchange that produces neighborhood stratification—which in turn bears directly on the lives of children with no choice in the matter.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSION

The results of the current analyses yield several implications for understanding the demography of neighborhood change and, by implication, neighborhood effects. First, a number of previously unobserved factors that represent hypothesized sources of selection bias in studies of neighborhood effects are, despite the litany of suspicions raised in the literature, of surprisingly minimal importance in actual or revealed neighborhood selection decisions. Residential stratification falls powerfully along racial/ethnic lines and socioeconomic location, especially income and education. These are for the most part the only surviving factors that explain a significant proportion of variance in neighborhood attainment conditions. Even after we introduced a variety of theoretically motivated covariates that captured largely unstudied aspects of locational attainment—such as depression, criminality, and social support—the substantive picture of our results was unchanged (cf. Figures 1 and 2). It follows that longitudinal studies accounting for neighborhood selection decisions and a fairly simple set of individual and family stratification measures may make for a reasonable test of neighborhood influences.

A second and related point is that despite accounting for changes in income, marital status, household size, and several other time-varying factors, we explain only about 10% of within-family change in neighborhood conditions occurring over the course of the study. The data reveal also that individuals experience significant change in their neighborhood environments even when they remain stationary. Clearly, individual characteristics and changes in individual life circumstances go only so far in explaining neighborhood stratification.

Third, however, we find that race/ethnicity interacts with changes in the racial composition of the origin neighborhood to influence the likelihood that an individual will choose to exit Chicago. Whites and Latinos living in neighborhoods with growing populations of nonwhites are more likely to exit the city, providing evidence that realized mobility arises, at least in part, as a response to changes in the racial mix of the origin neighborhood (Table 4). The same, however, is not true for black families—our data suggest that it is not African Americans’ preference for same-race neighbors that seems to matter as much as whites’ and Latinos’ eagerness to exit neighborhoods with growing populations of blacks. Ironically, then, neighborhood conditions appear to matter a great deal for influencing neighborhood selection decisions, suggesting a different kind of neighborhood effect—sorting as a social process.

Our findings based on neighborhood moves can be integrated with research on survey-reported preferences establishing that preferences for “out-group” neighbors fall along racial and ethnic lines, with whites consistently ranked as the preferred out-group, followed by Asians, Latinos, and African Americans (Charles 2001). African Americans typically report being the most open to living in integrated neighborhoods, yet they are thought of as the least desirable neighbors by whites, Latinos, and Asians. Although whites’ hostility toward the idea of integrated neighborhoods declined somewhat from the mid-1970s to the early 1990s (Farley and Frey 1994), the racial and ethnic divergence in neighborhood preferences shows up consistently over time and place (Charles 2001). Segregation is thus likely to reflect, in varying degrees, how race-specific perceptions and preferences translate into residential decisions (Quillian 2002:201).

Additional research is necessary to clarify how discrimination and revealed preferences for “in-group” and “out-group” neighbors interact to produce what appears to be a stratified pattern of neighborhood poverty traps (Sampson and Morenoff 2006). It is likely that some of the inequality reproduction we witness is “chosen” by the disadvantaged, not in the sense of an intended consequence for such but because some families, especially African American families, trade off more affluent (white) neighborhoods for ones perceived to be more hospitable and racially diverse, a not unreasonable calculus given the grim history of race relations in Chicago. Our data are also consistent with the notion that members of minority groups make residential sorting decisions based on their perceptions of a racialized hierarchy of places, even if felt to be unjust, and net of legal or outright institutional discrimination (Bobo and Zubrinsky 1996). Note that there is no significant exchange between African American and either mixed or Latino neighborhoods, regardless of economic status. These areas presumably do not offer vigorous opposition or institutional barriers of the sort proposed by place stratification theory.

Further work is also needed to address some of the limitations of the present study, such as the single site of study origin, the relatively small sample size, the relatively short duration of follow-up, and the restriction of inferences to families with children. Thus, for example, we cannot make claims about the mobility of single adults or generalize to the national scene.10 In many ways, the limitations of the PHDCN are the reverse of the PSID, which is not subject to any of these constraints. The flip side is that the PHDCN has several unique strengths, among them great diversity by race/ethnicity and immigration, a developmental focus that allows us to exploit a rich set of fixed and time-varying covariates, and the clustered neighborhood design that permitted analysis of the structural consequences of mobility through neighborhood flows.

In conclusion, our results show that the profound residential stratification visible in Chicago and beyond is reproduced as the complex result of choices actively made by movers and stayers of every racial/ethnic group. We are not suggesting that constraints on mobility are unimportant, only that they alone are inadequate to explain neighborhood stratification. This perspective views individuals as making heterogeneous choices and revealing their preferences about where to reside, with the parameters of choice tightly bounded by the stratified landscape in which choices are made. Discrimination continues, of course, especially in rental housing in white and mixed areas (Fischer and Massey 2004), such that anticipated discrimination may motivate nonwhite stayers. Preferences and structural constraints thus simultaneously and dynamically work together to yield a self-reinforcing cycle of inequality (Loury 2002), or what Tilly (1998) has more generally referred to as durable inequality. It follows logically that poverty traps are difficult to escape and likely to continue absent state-led interventions (e.g., deconcentration of public housing) or cultural changes that yield visions of social life in which ethnic and class diversity is seen as an urban amenity rather than a stigma.