Abstract

Many studies from developed countries show a negative correlation between family size and children’s schooling, while results from developing countries show this association ranging from positive to neutral to negative, depending on the context. The body of evidence suggests that this relationship changes as a society develops, but this theory has been difficult to assess because the existing evidence requires comparisons across countries with different social structures and at different levels of development. The world’s fourth most populous nation in 2007, Indonesia has developed rapidly in recent decades. This context provides the opportunity to study these relationships within the same rapidly developing setting to see if and how these associations change. Results show that in urban areas, the association between family size and children’s schooling was positive for older cohorts but negative for more recent cohorts. Models using instrumental variables to address the potential endogeneity of fertility confirm these results. In contrast, rural areas show no significant association between family size and children’s schooling for any cohort. These findings show how the relationship between family size and children’s schooling can differ within the same country and change over time as contextual factors evolve with socioeconomic development.

Numerous studies of educational attainment in the United States have shown that schooling is negatively correlated with sibship size. That is, children with fewer brothers and sisters obtain more schooling than those with more siblings. This negative association exists for many different measures of children’s human capital, including completed schooling, standardized test scores, and grades, and holds even after family socioeconomic characteristics are controlled (Blake 1989; Featherman and Hauser 1978; see Steelman et al. 2002 for a comprehensive review of this literature). In the sociological literature, this finding is often explained using an argument of finite resources: parents have limited time, money, and patience to devote to the education of their children, and those with fewer children can invest more per child. This theory of resource dilution fits well with the classic notion of the quality-quantity trade-off in family economics (Becker 1991; Becker and Tomes 1976).1

In recent years, two lines of research have called into question this seemingly robust negative relationship between family size and children’s schooling. First, some scholars have argued that this finding might be biased or spurious. If this negative association is explained by factors such as unobserved family characteristics that are not controlled in the analysis, then our understanding of the true relationship between these variables may be erroneous (Guo and VanWey 1999b). Moreover, few studies have addressed the concern that fertility and children’s schooling are jointly determined, despite evidence suggesting this is the case in some settings or sociohistorical periods (Axinn 1993; Caldwell, Reddy, and Caldwell 1985; Wolfe and Behrman 1984). Indeed, the very notion of a quality-quantity trade-off suggests that these processes are interrelated in complex ways that contradict the basic assumptions of regression analysis or fixed-effects models. Using data from Norway and Israel, for example, recent research in economics has shown that once fertility and child outcomes are modeled jointly, these variables display no meaningful association (Angrist, Lavy, and Schlosser 2006; Black, Devereux, and Salvanes 2005). Qian (2005), in contrast, found mixed results using a similar approach with data from China. She found that an increase from zero to one sibling has a positive effect on children’s schooling, while an increase from one to two siblings has a negative effect. Further research that addresses these issues, especially in a range of countries, will advance our understanding of the extent of such potential bias.

Second, a growing literature on the nature of these relationships in the developing world shows that the negative correlation found so consistently in more developed countries is not necessarily generalizeable. Instead, the association between family size and children’s outcomes varies greatly by time and place and ranges from negative to positive, depending on the specific context (see Buchmann and Hannum 2001 for an overview of this literature). A few examples suffice to show the range. The evidence from Thailand and Brazil suggests a negative association between family size and educational attainment (Knodel, Havanon, and Sittitrai 1990; Psacharopoulos and Arriagada 1989). Results from Vietnam show that the association is negative only for families with six or more children, and effects are modest when other family characteristics are controlled (Anh et al. 1998). The evidence from Botswana and Kenya, on the other hand, suggests the reverse is true: educational attainment has a positive relationship with family size (Chernichovsky 1985; Gomes 1984). Even within the same country, studies show that patterns differ by subgroup. Among Israeli Jews, for example, family size has a negative association with educational attainment. Among Israeli Muslims, who are less advantaged socioeconomically, live in less urban settings, have extended kinship networks, and have much higher fertility rates, family size and educational attainment are not associated (Shavit and Pierce 1991; but see Angrist et al. 2006).2

This array of evidence suggests that the relationship between family size and educational attainment is likely related to a society’s level of development, modes of production, and access to schooling, which in turn shape the relative influence of the family on the schooling of children (Desai 1995; King 1987; Lloyd 1994). In certain contexts or at certain stages of development, having more siblings to share household and labor market work may provide children with more resources for schooling. In some settings, the quality-quantity trade-off may not hold, and the desire to have better-educated children may not necessarily lead parents to choose smaller families (Gomes 1984; Mueller 1984). These macro socioeconomic mechanisms relating family size and children’s schooling might include the availability of schools, transportation and communication infrastructure, and participation in labor-intensive production such as agriculture. These mechanisms might be most apparent when comparing less developed rural contexts with more developed urban ones.

Furthermore, context-specific factors such as family organization and cultural roles determine wealth flows between parents and children, whether the burden of child rearing is limited to the nuclear family or extended across broader kin networks, whether and how much school-aged children work inside and outside the home, and whether these factors change as societies develop or as overall levels of educational attainment increase (Caldwell et al. 1985). In societies where parents bear most of the cost of schooling and where the costs are high, we might expect a negative relationship between family size and educational attainment. In societies with extended kinship networks and lower schooling costs, the relationship may be neutral or positive (Lloyd and Blanc 1996). The effects of family size on children’s schooling may also differ within families by factors such age, sex, or birth order of children (Lloyd and Gage-Brandon 1994; Parish and Willis 1993). Context-specific mechanisms relating family size to children’s schooling might include financial relationships within families, norms about how much schooling children should complete, parents’ preferences by child sex or birth order, labor market returns to schooling, and the costs of schooling.

The evidence also highlights the interdependence of family size, family structure, and educational attainment. Family size and educational attainment are likely to be jointly determined, at least to some degree, with families choosing the level of fertility that is likely to produce children with the preferred level of education for a given family, context, or society. The relationship between family size and children’s educational attainment can have demographic feedbacks as well. Small families may raise educational attainment, which in turn may lower fertility in the next generation. Moreover, if the effect of family size grows more negative or positive over time, these aggregate demographic relationships may intensify or accelerate.3

Over time, the relationship between family size and children’s schooling might change as development brings changes in income, consumption, urbanization, migration, educational opportunities, gender roles, and family organization. Government policies to invest in women’s schooling change women’s relative position in families and society and update norms about schooling girls. Of course, these updated norms also double the number of children families must educate relative to when only sons were schooled. Industrialization, modernization, and an expanding formal job sector increase the returns and hence the demand for schooling. But higher levels of schooling may be cost prohibitive despite families’ growing expectations for their children’s education. Other changing benefits of education might include more labor market opportunities for women and improvements in health and home production, which could also impact the relationship between family size and children’s education.

Socioeconomic development brings increased differentiation between urban and rural areas, which might translate to differences in the association between family characteristics and children’s schooling by geographical location. Urbanization improves access to schools by improving transportation and communication infrastructure and allowing closer proximity to this infrastructure. As the formal job sector grows, urban residents have better access to these jobs, which require more investment in schooling. Although city dwellers might be richer on average, costs of living are also higher there, making the marginal expense of an additional child different between urban and rural areas. The agrarian and informal economy of rural areas, in contrast, might allow families more flexibility in resource sharing and balancing home, work, and school responsibilities. Educational opportunities, however, might be quite limited in rural areas, and the formal sector more difficult to enter.

Taken together, the existing evidence from developed and developing nations suggests that there is no axiomatic relationship between family size and children’s schooling. Rather, this relationship varies by context and by levels of modernization and development. Much of the existing evidence, however, requires us to compare across different cultures and socioeconomic settings to determine the role of development in shaping the relationship between family size and children’s schooling. Although it may be tempting to use an array of cross-sectional evidence from across the world to infer something about the role of socioeconomic development, family organization, or government policies, comparing across different cultures and socioeconomic contexts can be difficult and misleading (Thornton 2001). Comparisons across time within the same country help with this problem.

Although numerous studies have examined the changing association between family size and children’s schooling across cohorts in the United States and Europe (de Graaf and Huinink 1992; Hauser and Featherman 1976; Kuo and Hauser 1995), few analysts have examined cohort trends in a developing country. The few studies that considered changes within the same developing country generally used only two cohorts (e.g., Hermalin, Seltzer, and Lin 1982; Pong 1997; Sudha 1997; see Parish and Willis 1993 for an exception). These offer only a limited view of the development process. One way to improve our understanding of these relationships is to study these associations across many different birth cohorts within one rapidly developing country. Indonesia offers such a context.

Indonesia, the world’s fourth most populous country in 2007, has experienced enormous socioeconomic growth in recent decades. Between 1970 and the late 1990s, Indonesia had one of the fastest-growing economies in the world. Over this period, the infant mortality and total fertility rate (TFR) declined dramatically, and life expectancy increased by almost 20 years (Indonesia Central Bureau of Statistics 2003; UNICEF 2000). There were also large gains in educational attainment, especially for women. Overall, participation in agriculture declined and industry grew. This setting provides a unique opportunity to examine how the relationship between family size and educational attainment changes as a society develops.

This study examines the association between family size/composition and educational attainment for four cohorts of Indonesians born between 1948 and 1991. To preview the results, large families are associated with significantly better educational outcomes for the oldest urban birth cohort but are associated with significantly poorer educational outcomes in more recent urban cohorts. Instrumental variables analysis shows that this negative relationship in the recent urban cohorts remains even in models that address the possibility that fertility and children’s schooling are jointly determined. In rural areas, in contrast, there is little evidence of a significant association between family size and children’s schooling for any cohort.

THE INDONESIAN CONTEXT

Indonesia is an archipelago nation of thousands of islands, hundreds of ethnicities, and nearly 235 million inhabitants in 2007. Following 300 years of Dutch colonization and several years of Japanese occupation during World War II, Indonesia gained independence in 1949. During the 1950s and 1960s, most Indonesians lived in rural areas, and poverty was endemic. The analysis starts with the 1948–1957 birth cohort, whose members were school-aged from the mid-1950s to the late 1960s. The Indonesian economy was largely agricultural in 1960, with about 75% of the labor force engaged in agriculture and 85% living in rural areas (UNICEF and Government of Indonesia 1988; Walton 1985). This was a period marked by severe economic strain, hyperinflation, and infant mortality rates of about 150 per 1,000 births (Hugo et al. 1987). Average life expectancy at birth was about 41 years, the real per capita gross national product (GNP) was $125 (USD), and only 27% of women ages 20 to 24 were literate (Hull 1987; Jones 1990).

A military coup in 1965 brought a shift in political power and a new focus on domestic development. Starting in 1967, the economy began to grow rapidly as the nation began to export oil and natural gas and attract foreign investment (Walton 1985). The 1958–1967 cohort was born during this time of transition and was school-aged just as the Indonesian economy began a period of massive growth. Between 1970 and the late 1990s, Indonesia went from being one of the poorest countries in the world to one at a middle level of socioeconomic development.

Indonesia used windfall profits from rising oil prices in the 1970s to finance an extensive educational expansion at the primary school level. From 1974 to 1979, the government built more than 61,000 primary schools and abolished tuition at public primary schools (Duflo 2001; Oey-Gardiner 1997). Primary school enrollments rose from 60% in 1974 to 94% by 1984 (Jones and Hull 1997). Meanwhile, the dramatic pace of socioeconomic development continued. Between 1970 and 1980, the infant mortality rate fell from 118 to 98 per 1,000 births, life expectancy rose from 47 to 53 years, and female literacy grew from 47% to 66% (Firman 1997; Iskandar 1997; Jones 1990; Jones and Hull 1997). By the early 1980s, only 55% of the labor force participated in agriculture, and real per capita GNP had risen to $447 (USD) (Hull 1987; Walton 1985). The 1968–1977 birth cohort was school-aged at the height of this period of growth and development.

After a period of turbulent oil prices and economic adjustment, the economy continued to grow in the 1980s. By the early 1990s, the infant mortality rate had declined to 66 per 1,000, female literacy was 93%, primary school enrollment had risen to 98%, and 31% of Indonesia’s population lived in urban settings (Cobbe and Boediono 1993; Jones and Hull 1997). The youngest birth cohort, born between 1978 and 1981, was school-aged in the late 1980s and 1990s after more than 20 years of sustained growth and development.

These four birth cohorts straddle another important part of Indonesia’s development experience. Historically in Indonesia, fertility was quite high and exhibited an inverted U-shaped pattern with women’s educational attainment (women with some primary or middle school experience had higher fertility than women with no schooling or with 12 or more years). This pattern was stronger in urban than in rural areas. Also, average fertility was higher in urban areas, and fertility exhibited a positive relationship with household income (Cobbe and Boediono 1993; Hull and Hull 1977).

The 1970s and 1980s marked the implementation of Indonesia’s state-sponsored family planning program (Gertler and Molyneaux 1994). The program distributed contraceptives and educated women on how to use them, promoted two-child families, and encouraged women to postpone marriage. The program aimed to both increase contraceptive supply and spur contraceptive demand by changing fertility preferences and norms. Concomitant with sustained economic growth and improvements in women’s socioeconomic position, the program was hugely successful. Between 1970 and the early 1990s, TFR declined from 5.6 to 2.9 children per woman (Gertler and Molyneaux 1994; Jones and Hull 1997). Women’s reports of their ideal family sizes also declined from an average of 4.2 in 1972 to about 3.2 in 1987 (Jones 1990). By the 1980s, the inverted U-shaped pattern of fertility by women’s schooling began to flatten out and disappear, especially in urban areas. Moreover, the positive correlation between household wealth and fertility declined, and a negative correlation emerged. The two oldest cohorts (1948–1957 and 1958–1967) were born before the implementation of the family planning program, and the more recent cohorts (1968–1977 and 1978–1981) were born after.

The formal school system in Indonesia has four basic levels. Primary school covers grades 1 to 6; junior secondary school covers grades 7 to 9; senior secondary school covers grades 10 to 12; and postsecondary covers all years from 13 onward. National final examinations separate each level of formal schooling. Urban-rural disparities in schooling were large in the 1960s and 1970s and have narrowed in more recent decades. Still, enrollment ratios after age 12 in rural areas in the 1990s are similar to those in urban areas in the 1970s (Oey-Gardiner 1997: figure 8.8). Although primary schooling has become widespread throughout Indonesia, higher educational levels remain quite expensive, and enrollment differences between urban and rural areas are substantial at these higher school levels (Oey-Gardiner 1997).

DATA AND METHODS

This analysis is based on the 1993 and 1997 waves of the Indonesian Family Life Survey (IFLS), a comprehensive longitudinal socioeconomic and health survey. The survey represents an area that includes 83% of Indonesia’s population (see Frankenberg and Thomas 2000 for detailed documentation on the IFLS). The sample used in this study includes approximately 3,200 families with more than 13,000 living children. All variables are measured as of 1997, except for those respondents who died between 1993 and 1997 or households not found in 1997 (about 5% of the 1993 sample). For these cases, I use the information provided in 1993, except for the schooling of respondents ages 19 or younger, which I leave missing because it is likely to be censored and systematically underreported when compared with the 1997 data. Overall, the data are quite complete, and the variables used in the analyses include little missing data.

For each ever-married female respondent (Indonesia is a society with nearly universal marriage and essentially no nonmarital fertility), I assemble a full count of all children, alive or dead, coresident or living elsewhere. I also identify the schooling of each woman’s husband, whether current or former. These women’s children are the units of analysis. The woman and her husband are the parents, and their children constitute the sibship.4 For mothers, fathers, and children, I measure educational attainment by years of completed schooling. I control for mother’s age in all models and report robust standard errors that correct for clustering of multiple children born to the same woman. I also control for province of residence, a key sampling stratum, in all statistical models.

Because urban and rural areas are quite different in Indonesia, especially in terms of resources and infrastructure, I estimate separate models by rural status. To identify whether a child grew up in an urban or rural location, I use the mother’s detailed migration history to determine each child’s region of residence when he or she was age 12. In their retrospective reports, women reported whether each of their places of residence was a village, small town, or big city. I classify villages as rural, and small towns and big cities as urban areas.5

I assemble four birth cohorts spanning ages 16 to 49 in 1997. The first three cohorts are restricted to families containing mothers who are at least 41 years old and children 20 years and older in order to measure completed fertility and completed schooling. This sample of children, born between 1948 and 1977, provides information on three broad cohorts: those born in 1948–1957, 1958–1967, and 1968–1977. I examine the relationship between family size and completed education by cohort and urban-rural status using ordered probit models with completed education classified in categories as the dependent variable and family size and household characteristics as independent variables.6 Children’s education is categorized in the most basic levels of the Indonesian educational system: none, primary (1–6 years), junior secondary (7–9 years), senior secondary (10–12 years), and postsecondary (13 or more years). To these three birth cohorts I add a fourth cohort of young children, those born between 1978 and 1981 (ages 16 to 19 in 1997). Here, there are no restrictions on the mother’s age, and fertility is not completed in many cases. Because many members of this most recent birth cohort have not completed their schooling, I use continuation beyond primary school as the measure of educational attainment for this cohort.

Educational attainment is correlated with household wealth, especially in developing countries (Chernichovsky and Meesook 1985; Filmer and Pritchett 1999; Hull and Hull 1977). The analyses shown below do not control for household wealth because the data do not include an appropriate measure of family wealth for most individuals used in this study, namely a measure of family wealth when the individuals were school-aged. The IFLS does collect extensive information about assets, consumption, and expenditures at the time of the survey, but most individuals included in this analysis were adults at that point (they were aged 16 to 49 in 1997). Thus, the measure of wealth comes after respondents’ schooling is completed and is likely endogenous to their educational attainment. Because using current wealth to predict previous schooling is problematic, I report results from models that do not include this measure. Mother’s and father’s schooling, which serve as noisy proxies for family wealth (Hull and Hull 1977), are controlled in all models.

Sensitivity tests confirm that the results shown below are robust to omitted measures of household wealth.7 For respondents in the youngest birth cohort, who were aged 12 to 15 in 1993, including 1993 log per capita expenditures of their mothers’ household does not change the results in either the exogenous or instrumented models. The results for the other cohorts are also quite consistent. For these older cohorts, excluding individuals who coreside with their mothers and are not enrolled in school and including 1993 log per capita expenditures for their mothers’ household also produces quite similar results despite the reduced sample size. Moreover, the overall pattern of results—the association between family size and children’s schooling going from positive to neutral to negative across cohorts—remains unchanged with or without a measure of family wealth.

Another methodological issue involves the effect of mortality on the sample. Developing countries generally have high rates of infant and child mortality. This means that a full count of a woman’s live births may not represent the actual number of living siblings a child had while growing up. Nor is it obvious which count represents the correct measure of sibship size. Infants who die soon after birth may not compete with older children for resources that relate to schooling. But sick infants may require much of their parents’ attention, leaving older children with increased responsibilities within the household and less time for school. In the results below, I use a count of living siblings as the measure of family size. This measure facilitates comparisons across these Indonesian cohorts, which have experienced steady declines in infant mortality. The full count of all live births would implicitly embed this changing pattern of infant mortality in the construct. In these Indonesian cohorts, including controls for the number of siblings who have died does not change the estimated effects of family size or any of the other independent variables in the analysis. In other settings, however, these different measures of family size may give different results.

Selective mortality may be a potential problem in at least two other ways. First, the oldest cohort (born 1948–1957) may be positively selected because their mothers, who are on average in their 60s in 1997, survived long enough to appear in the IFLS sample. If the relationship between family size and children’s schooling differs by mother’s schooling, and mothers with less schooling are systematically censored from the sample, then the results may be biased. Fortunately, analyses confirm that there are no meaningful interactions between family size effects and women’s schooling for the oldest cohort, which is the cohort most likely to suffer from selective survival of mothers. Second, the IFLS does not collect information on the schooling of children who died more than 12 months before the survey, or detailed pregnancy histories from women over age 49. This means that children identified as the “oldest” may not be, strictly speaking, firstborn if the women had any children born earlier who had died. Thus, measures of being the oldest boy or girl in a family represent being the oldest living child at the time of the survey.

Analyzing the relationship between family size and children’s schooling also involves grappling with the difficult problems of unobserved heterogeneity and joint determination. If parents have characteristics not captured by the included covariates that are correlated with family size and children’s schooling, or if parents choose their family size with an eye to how much schooling they would like to provide their children, then standard regressions of the type presented here provide biased estimates of the effect of family size on children’s education. Although most of the research on the effects of family size on children’s outcomes assumes that fertility is exogenous to children’s outcomes (see DeGraff and Bilsborrow 2003 for a partial review of the literature in this regard), some recent research has tried to address these concerns through the use of fixed-effects designs or by using twinning as a “natural experiment” that causes an exogenous increase in fertility.

Fixed-effects models net out a constant individual or group-level factor that is unobserved and is usually a component of the error term (see, e.g., Guo and VanWey 1999b, which used repeated observations on individuals, or Parish and Willis 1993, which used differences between siblings).8 The fixed-effect approach assumes that the unobserved characteristics are not related to the dependent and independent variables in complex ways. In particular, the unobserved effect is assumed to be additive, meaning that the effect of the unobserved factor does not differ across different levels of the other regressors. To use a concrete example, this means assuming that the effect of parents’ unobserved preferences for child’s schooling does not differ by child’s sex or birth order. The fixed-effect approach also assumes that the effect of the unobserved factor on the dependent variable does not change over time.

The fixed-effect approach, however, does nothing to resolve concerns about more complex relationships such as “trade-offs” or jointly determined processes. In this case, the analyst might model both processes together (as in a simultaneous equation model with exclusion restrictions) or rely on an experiment that provides exogenous variation on one of the jointly determined processes without affecting the other one. Researchers in economics have utilized twinning as an instrument to measure the exogenous effects of fertility on outcomes such as labor force participation (Angrist and Evans 1998; Jacobsen, Pearce, and Rosenbloom 1999; Rosenzweig and Wolpin 1980a), women’s economic outcomes (Bronars and Grogger 1994), and children’s schooling (Angrist et al. 2006; Black et al. 2005; Rosenzweig and Wolpin 1980b). The instrumental variables approach and the use of twins in particular have their own set of shortcomings.9 But there is also a major practical problem with using twins as instruments: twinning is a rare event and one that is difficult to capture in sample surveys. In this paper, I use an alternative instrument that relies on women’s report of miscarriages, which are more common events and are widely available in survey data. I use this approach to test the robustness of the results to assumptions about joint determination. I discuss the approach in more detail below.

RESULTS

Changing Patterns Across Cohorts

Table 1 presents sample means and proportions for the full sample and each birth cohort. Families are relatively large in this Indonesian sample. In the first three birth cohorts, children have an average of 4.5 living siblings. The average number of children ever born ranges from about 7 in the oldest cohort to about 6.4 in the 1968–1977 cohort. Family sizes are smaller in the most recent cohort, but this is also the cohort in which some of the mothers are still in their peak childbearing years. In general, one- and two-child families are uncommon in Indonesia. In the first three birth cohorts, families with three to eight children are relatively common. Despite a clear trend toward smaller families over time, the range across cohorts of the number of children born to Indonesian parents is quite wide and fairly high for the years covered by these data.

Table 1.

Sample Means and Proportions: IFLS

| Born 1948–1957 | Born 1958–1967 | Born 1968–1977 | Born 1978–1981 | All Sample Children | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Living Siblings | 4.6 (0.07) | 4.6 (0.04) | 4.4 (0.03) | 3.8 (0.04) | 4.3 (0.02) |

| Number of Siblings Who Died | 1.4 (0.05) | 1.2 (0.03) | 1.0 (0.02) | 0.7 (0.03) | 1.0 (0.01) |

| Average Number of Children Ever Born (row 1 + row 2 + 1) | 7.0 | 6.8 | 6.4 | 5.5 | 6.3 |

| Family Size (living children) | |||||

| 1 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| 2 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.06 |

| 3 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.13 |

| 4 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.17 |

| 5 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.17 |

| 6 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.16 |

| 7 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.11 |

| 8 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| 9 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| 10 or more | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Child’s Education (years) | 6.5 (0.13) | 7.1 (0.09) | 8.5 (0.07) | 8.3 (0.06) | 7.8 (0.04) |

| Child’s Educational Level | |||||

| None | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Elementary school | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.33 | 0.43 |

| Junior secondary school | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.28 | 0.17 |

| Senior secondary school | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 0.25 |

| Postsecondary | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| Gender Gap in Education (M – F) | 1.8 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.9 |

| Mother’s Education (years) | 1.7 (0.08) | 2.3 (0.06) | 3.3 (0.05) | 4.0 (0.08) | 3.0 (0.03) |

| Father’s Education (years) | 3.6 (0.11) | 4.0 (0.07) | 4.9 (0.06) | 5.5 (0.09) | 4.6 (0.04) |

| Mother’s Age | 67.1 (0.22) | 60.6 (0.15) | 52.5 (0.12) | 43.8 (0.17) | 54.7 (0.11) |

| Child’s Age | 43.4 (0.08) | 33.9 (0.05) | 24.5 (0.04) | 17.5 (0.02) | 28.0 (0.09) |

| Rural Residence at Age 12 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.72 |

| Oldest Boy in Family | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.23 |

| Oldest Girl in Family | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.25 |

| Child Under Age 6 in Sibship | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.06 |

| Number of Observations | 1,612 | 3,632 | 5,329 | 2,770 | 13,343 |

Notes: Numbers in parentheses are standard errors. Descriptive data are weighted using sample probability weights. Because schooling and family size are not completed for those in the 1978–1981 cohort, these means are not directly comparable to the other three cohorts.

Average levels of schooling have increased steadily across birth cohorts.10 The proportion of those with no schooling decreased steadily, while the proportion of those with senior and postsecondary schooling increased in the cohorts with completed schooling (1948–1977). At the same time, differences in educational attainment by sex changed from a 1.8-year advantage for males in the oldest cohort to parity in the most recent cohort.11

Table 2 shows the distribution of children’s schooling by cohort and place of residence for the first three birth cohorts. For those living in urban areas at age 12, average levels of schooling increased by about 1.6 years across the three birth cohorts (from about 9.3 years to 10.9 years). The median level of schooling increased from completing junior secondary to completing senior secondary, and the top of the distribution also increased.12 Most of the educational gains in the urban cohorts occurred at the bottom of the education distribution. The bottom decile went from having only some primary schooling to completing that level, and the 25th percentile went from completing primary to completing junior secondary.

Table 2.

Distribution of Children’s Education (years of school completed) by Cohort: IFLS

| Percentiles |

Mean | N | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 90 | |||

| Urban 1948–1957 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 9.3 | 559 |

| Urban 1958–1967 | 3 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 17 | 10.0 | 1,203 |

| Urban 1968–1977 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 15 | 10.9 | 1,911 |

| Rural 1948–1957 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 5.4 | 1,053 |

| Rural 1958–1967 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 6.0 | 2,429 |

| Rural 1968–1977 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 7.6 | 3,418 |

Notes: N = 10,573. The table includes only cohorts with completed education. Descriptive data are weighted using sample probability weights.

In contrast, those who grew up in rural areas have substantially lower levels of average attainment and a more disadvantaged distribution of schooling across all cohorts. Average attainments are three to four years lower here than in the urban cohorts. The median level of schooling remained stable at about six years across all rural cohorts, although the inter-quartile range shifted from straddling the primary grades to a range that includes junior and senior secondary grades. For the bottom rural decile, the floor increased from no schooling to an average of three years. Those in the top decile in rural areas achieved relatively high attainments across all cohorts. Even in the top decile, however, few individuals who grew up in rural areas progressed beyond senior secondary.

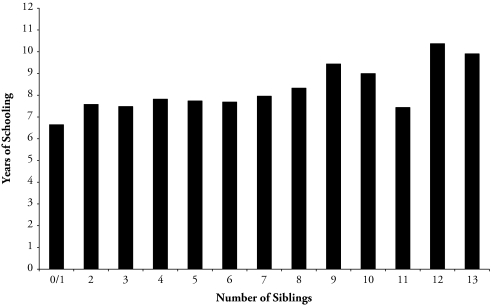

Figure 1 shows completed schooling by number of siblings for those born between 1948 and 1977 (ages 20 to 49 in 1997). Respondents with zero or one sibling, a rare sibship size in this sample, have about one year less schooling than those with two to seven siblings. Those with eight or more siblings complete more schooling on average. Remarkably, children’s education in the cross section displays little relationship with family size for those with two to seven siblings, a substantial range by most demographic standards. Even more surprisingly, the cross-sectional data show a positive relationship between very large families and children’s schooling.

Figure 1.

Educational Attainment by Family Size in Indonesia, Adults Ages 20–49: IFLS (N = 10,573)

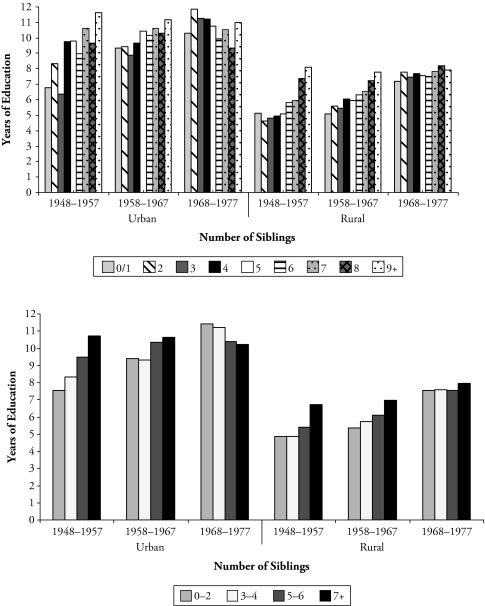

This cross-sectional view, however, hides substantial variation by cohort and place of residence. Figure 2 shows the same sample as Figure 1, stratified by birth cohort and urban-rural residence. The top panel provides a detailed specification of number of siblings. The bottom panel collapses adjacent categories to provide a more tractable grouping for analysis. Comparing the two graphs shows that the more parsimonious grouping stays true to the trends apparent in the more detailed representation. Figure 2 also highlights the dramatic increase in schooling in Indonesia over time and the large differences in schooling by urban-rural residence.13

Figure 2.

Educational Attainment by Family Size and Birth Cohort, Adults Ages 20–49: IFLS (N = 10,573)

In the first two urban birth cohorts (1948–1957 and 1958–1967) those with four or fewer siblings have lower educational attainment than those with five or more siblings. In the 1948–1957 cohort, for example, those with five or six siblings have an average of 1.5 more years of schooling than those with fewer siblings, while those with seven or more siblings have about 2.5 more years of schooling, on average. This relationship is quite different in the 1968–1977 urban birth cohort. This cohort shows large gains in average levels of schooling overall and has a negative relationship between family size and children’s schooling. Each larger category of siblings is associated with lower levels of average schooling, with a difference of about 1.2 years in average attainment between the smallest and largest sibship categories.

In the first two rural cohorts, there is a positive relationship between family size and completed schooling. In the 1948–1957 rural cohort, those from the largest sibships have the highest levels of schooling, and this association is monotonically positive for those in the 1958–1967 rural cohort. In contrast, the most recent rural cohort exhibits no relationship between family size and educational attainment, a quite different pattern than has emerged for its urban counterpart. The patterns in Figure 2 suggest that the overall association between family size and children’s schooling has been changing across Indonesian cohorts and differs by geographical area. The offsetting patterns in Figure 2 also explain the apparent lack of a pattern when family size and schooling are examined in the pooled cross section (as in Figure 1).

Table 3 shows results from multivariate models that examine the relationship between family size and completed education, controlling for other family characteristics.14 For each cohort and place of residence, I show both linear and categorical estimates of the effects of family size. All models control for mother’s and father’s education, child’s sex, whether the child was the oldest child in the family, child’s age, mother’s age, and the regional province in which the household was located. Parents’ education, child’s sex, and birth order are mediators that have been shown relevant in other studies of these relationships. The remaining variables control for sample composition.15 Models 3.1 and 3.2, shown in the first two columns, give estimates for the oldest urban birth cohort. For this cohort, the association between family size and children’s schooling is positive. Holding all else constant at the sample mean, an additional sibling increases the probability of being in the highest education category by about .01. This positive association disappears in the 1958–1967 urban cohort (Models 3.3 and 3.4). In this urban cohort, there is no meaningful relationship between family size and children’s schooling net of family and individual characteristics. For the 1968–1977 urban cohort, however, a negative association emerges (Models 3.5 and 3.6). For this birth cohort, an additional sibling decreases the probability of being in the highest education category by about .013. The results are similar for both the linear and categorical specifications of family size. Over a span of three birth cohorts, the association between family size and children’s schooling goes from positive to neutral to negative for those who lived in urban areas at age 12.

Table 3.

Ordered Probit Models Predicting Completed Education, by Cohort and Rural Residence: IFLS

| Urban 1948–1957 |

Urban 1958–1967 |

Urban 1968–1977 |

Rural 1948–1957 |

Rural 1958–1967 |

Rural 1968–1977 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 3.1 | Model 3.2 | Model 3.3 | Model 3.4 | Model 3.5 | Model 3.6 | Model 3.7 | Model 3.8 | Model 3.9 | Model 3.10 | Model 3.11 | Model 3.12 | |

| Number of Siblings (linear, 0–14) | 0.064* (0.025) | 0.010 (0.020) | –0.052* (0.017) | 0.025 (0.020) | 0.005 (0.015) | –0.012 (0.013) | ||||||

| Number of Siblings (categories) (ref. = 7 or more) | ||||||||||||

| 0–2 | –0.363† (0.188) | 0.016 (0.137) | 0.323* (0.121) | –0.150 (0.136) | –0.037 (0.103) | 0.105 (0.089) | ||||||

| 3–4 | –0.441* (0.193) | –0.184 (0.116) | 0.198† (0.113) | –0.223† (0.127) | –0.024 (0.096) | 0.010 (0.082) | ||||||

| 5–6 | –0.408* (0.156) | –0.068 (0.119) | 0.188† (0.110) | –0.184 (0.136) | –0.097 (0.095) | –0.031 (0.085) | ||||||

| Mother’s Education | 0.071* (0.024) | 0.073* (0.023) | 0.106* (0.012) | 0.107* (0.012) | 0.129* (0.012) | 0.129* (0.012) | 0.136* (0.023) | 0.139* (0.024) | 0.116* (0.014) | 0.117* (0.014) | 0.116* (0.010) | 0.116* (0.011) |

| Father’s Education | 0.077* (0.018) | 0.080* (0.018) | 0.109* (0.012) | 0.109* (0.012) | 0.090* (0.010) | 0.091* (0.010) | 0.126* (0.017) | 0.124* (0.017) | 0.100* (0.010) | 0.100* (0.010) | 0.106* (0.009) | 0.107* (0.009) |

| Female | –0.478* (0.160) | –0.489* (0.161) | –0.113 (0.092) | –0.125 (0.092) | –0.083 (0.071) | –0.087 (0.071) | –0.533* (0.126) | –0.538* (0.125) | –0.385* (0.071) | –0.383* (0.072) | –0.168* (0.053) | –0.169* (0.053) |

| Oldest Boy | 0.041 (0.148) | 0.012 (0.150) | –0.004 (0.098) | –0.011 (0.099) | –0.113 (0.077) | –0.098 (0.076) | 0.128 (0.101) | 0.112 (0.101) | –0.139* (0.066) | –0.145* (0.067) | –0.029 (0.057) | –0.042 (0.057) |

| Oldest Girl | 0.058 (0.126) | 0.022 (0.131) | –0.261* (0.094) | –0.261* (0.091) | –0.140† (0.078) | –0.120 (0.078) | 0.042 (0.105) | 0.034 (0.105) | –0.079 (0.066) | –0.087 (0.066) | –0.178* (0.051) | –0.192* (0.051) |

| Log-Likelihood | –701 | –699 | –1,415 | –1,412 | –2,145 | –2,146 | –1,132 | –1,131 | –2,825 | –2,823 | –3,970 | –3,968 |

| N | 559 | 1,203 | 1,911 | 1,053 | 2,429 | 3,418 | ||||||

Notes: Total N = 10,573. Robust standard errors are shown in parentheses. Cut-point parameters are not shown. All models control for child’s age, mother’s age, and province of residence (coefficients not shown).

p < .10;

p < .05

In these urban birth cohorts, daughters are disadvantaged in the oldest cohort but not in the more recent ones—a sign of the closing gender gap in schooling at least in urban areas. At the same time, being the oldest girl in a family is a disadvantage in more recent urban cohorts but not in the oldest cohort. This pattern might reflect emerging inequality within the family or capture a transitory period effect during a time of rapid school expansion. Girls who were born at the very beginning of this cohort may not have enjoyed the full benefit of the massive school expansion of this period. But the difference between the estimate for being the oldest boy (which is not significant) and being the oldest girl suggests an alternative possibility. Parents’ attitudes toward schooling girls may have evolved over this period to the benefit of younger girls.16

Models 3.7 to 3.12 show the results for the three rural birth cohorts. In these rural cohorts, there is no significant association between family size and children’s schooling once other family characteristics are controlled. The categorical specification for the oldest rural birth cohort (Model 3.8) suggests a marginally significant negative association of having three or four siblings relative to having seven or more. The coefficients, however, are not jointly significant, and the linear term is also not significant. This marginally positive association between larger families and children’s schooling in the oldest rural cohort is consistent with the relationship found in the oldest urban cohort. Indeed, the overall pattern of results for the rural cohorts, although smaller in magnitude and not significant, is similar to that found in the urban cohorts.17 I discuss possible explanations for these urban-rural differences in more detail below.

Daughters complete less schooling than sons across all rural cohorts, although this disadvantage diminishes over time. The marginal effect of being female on the probability of being in the highest education category shrinks from –.027 to –.01. Nonetheless, women have not made the same educational gains relative to men in rural areas as they have in urban settings, another example of differential associations by levels of socioeconomic development (in this case by urban-rural status within the same country). The association between being the oldest child and completed schooling shows two interesting patterns. The coefficient for being the oldest boy is negative in the middle rural cohort, and the coefficient for being the oldest girl is negative in the younger rural cohort. These patterns suggest that as schooling became more widely available in Indonesia, boys first benefited more than girls, and younger children benefited more than older children. In Indonesia, however, these patterns appear to be related to the availability of schools rather than strong preferences by birth order. This pattern does not exist for older boys in urban areas and dissipates for older girls by the 1968–1977 urban cohort.

Overall, these findings reproduce the trends shown in Figure 2 in a multivariate frame-work, particularly for the urban birth cohorts. Historically in Indonesia, children from large families living in urban areas obtained more schooling than those from smaller families, holding other family characteristics constant. In recent urban cohorts, this positive association between large families and children’s schooling has disappeared, and a negative association has emerged in the most recent cohort. In rural areas, there is no significant association between family size and educational attainment in any cohort once other factors are controlled.

The results in Table 4 extend the analysis to the most recent cohort of children available in the 1997 IFLS, those ages 16 to 19 in 1997. Because many members of this cohort have not completed their schooling, these analyses rely on continuation beyond primary school rather than completed education. About three-fourths of IFLS children ages 6 to 19 were enrolled in school in 1997. In both rural and urban areas, at least 95% of children ages 8 to 12 were enrolled in school. After age 12, enrollment by age drops faster in rural areas, with about three-fourths of urban children still enrolled at age 16 compared with about half of rural children age 16.18 While Indonesia has achieved nearly universal primary school enrollment, enrollment proportions drop rapidly at ages associated with secondary school and differ considerably between urban and rural areas.

Table 4.

Binary Probit Models Predicting School Enrollment and Continuation Beyond Primary School for the 1978–1981 Cohort (ages 16–19 in 1997): IFLS

| Completed Junior Secondary School |

Entered Senior Secondary School |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban |

Rural |

Urban |

Rural |

|||||

| Model 4.1 | Model 4.2 | Model 4.3 | Model 4.4 | Model 4.5 | Model 4.6 | Model 4.7 | Model 4.8 | |

| Number of Siblings (linear) | –0.087* (0.032) | –0.017 (0.023) | –0.089* (0.030) | –0.026 (0.026) | ||||

| Number of Siblings (ref. = 5 or more) | ||||||||

| 0–2 | 0.457* (0.166) | 0.195† (0.114) | 0.315* (0.143) | 0.212† (0.122) | ||||

| 3–4 | 0.196 (0.127) | 0.132 (0.093) | 0.198 (0.122) | 0.132 (0.098) | ||||

| Mother’s Education | 0.135* (0.020) | 0.135* (0.020) | 0.120* (0.015) | 0.121* (0.015) | 0.085* (0.017) | 0.086* (0.017) | 0.115* (0.015) | 0.116* (0.015) |

| Father’s Education | 0.081* (0.016) | 0.081* (0.016) | 0.123* (0.012) | 0.122* (0.012) | 0.087* (0.015) | 0.086* (0.015) | 0.117* (0.013) | 0.116* (0.013) |

| Female | 0.344* (0.131) | 0.332* (0.131) | –0.064 (0.092) | –0.062 (0.092) | 0.213† (0.119) | 0.204† (0.119) | –0.002 (0.101) | –0.001 (0.101) |

| Oldest Boy in Family | 0.081 (0.155) | 0.063 (0.160) | 0.126 (0.105) | 0.100 (0.106) | 0.215 (0.135) | 0.239† (0.135) | –0.022 (0.113) | –0.043 (0.112) |

| Oldest Girl in Family | –0.066 (0.156) | –0.062 (0.157) | 0.012 (0.103) | –0.017 (0.103) | 0.040 (0.136) | 0.077 (0.135) | –0.213† (0.115) | –0.235* (0.115) |

| Child Under Age 6 in Sibship | 0.173 (0.157) | 0.162 (0.162) | –0.131 (0.105) | –0.099 (0.102) | 0.177 (0.147) | 0.127 (0.145) | –0.142 (0.111) | –0.118 (0.109) |

| Constant | –0.937* (0.480) | –1.332* (0.511) | –1.149* (0.311) | –1.377* (0.348) | –1.561* (0.444) | –1.869* (0.478) | –1.589* (0.340) | –1.825* (0.379) |

| Log-Likelihood | –441 | –441 | –932 | –930 | –548 | –550 | –765 | –764 |

| N | 1,059 | 1,059 | 1,711 | 1,711 | 1,059 | 1,059 | 1,711 | 1,711 |

Notes: All models control for child’s age in single years, mother’s age, and province of residence (coefficients not shown). Sibling categories in models 4.4 and 4.8 are not jointly significantly different that zero.

p < .10;

p < .05

Table 4 shows results from binary probit models that examine the likelihood of completing junior secondary schooling (completing grade 9) and entering senior secondary (completing at least grade 10) by urban-rural residence. The models also include a measure for having a child under age 6 in the sibship. This measure is intended to capture whether having a very young sibling interferes with school investment for older siblings. Models are restricted to children ages 16 to 19 at the time of the survey so that only those who are old enough to have made these transitions are considered.19 Because families are smaller in this cohort, the categorical version of family size is capped at five or more children (rather than at seven or more, as in Table 3) for this birth cohort.

In the 1978–1981 urban birth cohort, larger families are associated with a lower likelihood of completing junior secondary schooling (Model 4.1). With covariates held at the sample means, an additional living sibling is associated with a .02 decrease in the probability of entering junior secondary school. Model 4.2 replicates this finding with a categorical version of number of siblings. Having two or fewer siblings (versus five or more) reduces the likelihood of transitioning from primary to junior secondary school. In contrast, family size and the likelihood of completing junior secondary school are not significantly associated for children living in rural areas at age 12 (Models 4.3 and 4.4). The results are similar for the likelihood of entering senior secondary school.20 With other family and individual characteristics held constant, the association of family size and entering senior secondary school is negative and significant in urban areas (Models 4.5 and 4.6) but not significant in rural areas (Models 4.7 and 4.8). With covariates held at the sample means, an additional living sibling reduces the predicted probability of entering senior secondary school by about .03 in urban areas. Having a young child in the household is not associated with the likelihood of making either school transition. This result does not differ by the sex of the index child (interaction models not shown).

Differences by sex and birth order are consistent with the patterns shown in Table 3. For urban cohorts, differences by birth order have disappeared, and an advantage for girls has emerged. This advantage likely reflects girls’ lower rates of school failure and grade retention rather than any emerging sex preference. Indeed, by senior secondary school, this female advantage has become only marginally significant in urban areas. For rural areas, disadvantages by sex and birth order have largely disappeared, reflecting growing school opportunities for all children and particularly for girls in these areas (albeit only at these lower levels of schooling). The one exception to this pattern is that older rural girls are still marginally less likely to enter senior secondary school relative to their younger siblings.

Testing for the Potential Endogeneity of Fertility

The analyses above provide ample evidence for a correlation between family size and children’s schooling but do not address the concern that these processes may be jointly determined. To assess the sensitivity of the results to assumptions about the exogeneity of fertility, I use instrumental variables analysis (IV) as an alternative estimation strategy (Wooldridge 2002). One way to instrument completed fertility is to find a physiological (rather than behavioral) trait that is exogenous and heterogeneously distributed among individuals, which affects completed fertility but is independent of preferences for family size. As discussed above, twinning has been the most widely utilized instrument of this type in previous work. A few studies, however, have also used miscarriages to instrument fertility (Hotz, McElroy, and Sanders 2005; Hotz, Mullin, and Sanders 1997). Once maternal age and behaviors such as smoking and drinking are controlled, miscarriages represent an exogenous and random shock to a woman’s fertility (Kline, Stein, and Susser 1989; Leridon 1977; Porter and Hook 1980). Miscarriages are involuntary, spontaneous fetal deaths that reduce the number of conceptions that result in live births, and therefore represent lost fertility exposure time (Bongaarts and Potter 1983; Casterline 1989; Leridon 1977). As described by Casterline (1989:81–82), “[a]ccepted estimates of overall spontaneous loss rates of 20 percent of recognized pregnancies (Bongaarts and Potter, 1983) thus imply two and one-half months of time lost involuntarily for every live birth, on average. In most societies this represents a reduction in fertility of 5–10 percent from levels expected in the absence of pregnancy loss.” Net of age and behavior, women who experience many miscarriages may fail to achieve their desired family size despite their preferences. Factors such as socioeconomic and nutrition status are not associated with miscarriage rates (Kline et al. 1989).21

Using miscarriages to instrument fertility is a different approach than using twins. Miscarriages represent an exogenous constraint on fertility, while twins represent an exogenous “extra” child. Women who experience many miscarriages may end up with lower fertility than they had hoped for, while women with twins may end up with more children than desired. Ideally, one would test the robustness of the results to both these approaches. However, this is untenable in most sample surveys because twinning is a rare event. Miscarriages, in contrast, are a more common event and are recorded in many demographic surveys. When appropriate, miscarriages offer an alternative approach to measuring exogenous shocks to fertility.

Using the number of miscarriages a woman experiences as an instrument for completed fertility does not sufficiently control for underlying parental preferences about family size, which may be correlated with preferences about children’s schooling (see Rosenzweig and Wolpin 1980a for a related discussion regarding twins). Those who desire very large families may have many pregnancies and therefore experience more miscarriages because of their increased exposure to the risk of miscarriage (Kline et al. 1989). To address this, I adjust number of miscarriages by regressing it on total number of pregnancies, pregnancies squared, and pregnancies cubed, using a Poisson model. I then use the residual from this regression, which is orthogonal to number of pregnancies, along with the residual squared and cubed as the instruments. This adjusts the count of miscarriages for underlying family size preferences in a flexible and nonlinear way.22

Two important limitations to using miscarriages to instrument fertility include women’s knowledge of having had a miscarriage in the first place and recall error in the reporting of miscarriages. Women’s knowledge and recall about miscarriages may vary by their level of schooling and urban-rural residence, and both variables are controlled in all models. Women may also forget to report miscarriages that occurred long ago as these events lose salience in their mental record of their reproductive history (Casterline 1989; Panis and Lillard 1994). In the current analysis, the issue of recall error seems particularly problematic for the older cohorts. I exclude these cohorts from the IV analyses and focus only on testing the robustness of the negative association between family size and children’s schooling in the most recent cohorts. The endogeneity of fertility is also more likely to be relevant for more recent cohorts, who experienced the widespread distribution of modern contraception after the 1970s.

The analyses in the previous section use ordered probit models because this specification offers a flexible and less parametric way to capture educational attainment. Measured in years of schooling, educational attainment is inherently discrete and ordered and is well-suited to this statistical modeling strategy. But combining IV with these types of nonlinear models is quite complex and generally not well identified. The best-developed IV methods use two-stage least squares (2SLS) or binary probit models. Although, in general, ordered probit and ordinary least squares (OLS) models do not necessarily produce the same results, for the case of educational attainment in this IFLS sample, the substantive results are the same for both methods. Therefore, I estimate the IV models using 2SLS and IV probit models. Instruments that are too weakly correlated with the endogenous regressor pose another methodological problem for IV (Bound, Jaeger, and Baker 1995; Hall, Rudebusch, and Wilcox 1996; Shea 1997; Staiger and Stock 1997), but standard metrics show that the instruments used here are sufficiently strong. The IV models shown in Table 5 all have first-stage F statistics larger than 12. The 2SLS models also have high values for the first-stage partial R2. 23

Table 5.

Summary of Instrumental Variables Results: IFLS

| Urban 1968–1977, Years of School Completed (linear) | Urban 1978–1981, Complete Junior Secondary (0/1) | Urban 1978–1981, Enter Senior Secondary (0/1) | Rural 1968–1977, Years of School Completed (linear) | Rural 1978–1981, Complete Junior Secondary (0/1) | Rural 1978–1981, Enter Senior Secondary (0/1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Siblings, Treated as Exogenous | –0.138* (0.050) | –0.087* (0.032) | –0.089* (0.030) | –0.017 (0.040) | –0.017 (0.023) | –0.026 (0.026) |

| Number of Siblings, Instrumented | –0.260† (0.144) | –0.110 (0.085) | –0.143† (0.079) | –0.167 (0.117) | –0.070 (0.049) | –0.054 (0.055) |

| F (IV first stage) | 18.18 | –– | –– | 24.78 | –– | –– |

| Partial R2 (IV first stage) | 0.146 | –– | –– | 0.130 | –– | –– |

| N | 1,911 | 1,059 | 1,059 | 3,418 | 1,711 | 1,711 |

Notes: The exogenous regressions for years of school completed are estimated using OLS, and those for school attendance are estimated using probit models. The exogenous OLS results are available from the author. The exogenous probit models are shown in Table 4. The IV coefficients are estimated using 2SLS for years of school completed and maximum likelihood IV probit for school attendance. The instrument is described in the text. The full IV results are available from the author.

p < .10;

p < .05

Table 5 summarizes the IV results. The first row shows estimates for number of siblings treated exogenously from OLS models corresponding to Table 3 (models not shown) and the probit models shown in Table 4. All models control for child’s and mother’s age and therefore mother’s age at birth. The models do not control for smoking or drinking because these behaviors are rare among women in Indonesia. Less than 5% of IFLS women reported having ever smoked, and controlling for this behavior does not change the results shown. Alcohol consumption is even more uncommon in this predominantly Muslim country, and the IFLS does not include this measure.

Overall, the IV models show the same patterns as the models that treat fertility as exogenous, but the coefficients are not estimated as precisely. For the 1968–1977 urban birth cohort, the instrumented effect of number of siblings is negative and marginally significant, suggesting that children with more siblings obtain less schooling in more recent urban cohorts. The effect of family size is also negative and marginally significant for the model predicting entry into senior secondary school. In the most recent urban birth cohort, children with more siblings are less likely to make this transition. For those cohorts in which the concern of the endogeneity of fertility and a spurious negative effect of family size on children’s schooling is most likely, the IV results support the results of the analyses that treat fertility as exogenously determined. The IV results lack power for the two recent rural cohorts. Here, none of the models yield a significant relationship between family size and children’s schooling, although the patterns are suggestive and similar to those in the earlier models.

DISCUSSION AND SUMMARY

In Indonesia, the relationship between family size and children’s schooling is not uniformly positive or negative. Rather, there are important differences by cohort and urban-rural residence. For rural cohorts, there is little evidence of a statistically significant association between family size and children’s schooling, a finding that is consistent in all birth cohorts. In contrast, in urban areas, this association evolved from positive to neutral to negative over a span of 30 years. For the 1948–1957 urban cohort, larger families were associated with more schooling. This positive relationship diminished over time, and a negative relationship developed in the 1968–1977 cohort and remains for the most recent birth cohort (1978–1981). Although the estimated effects are smaller and not statistically significant, this evolving pattern is also apparent across the rural cohorts, suggesting that as rural areas continue to develop these associations may change.

In both rural and urban areas, differences in schooling by sex and birth order also changed over time. In the oldest urban cohort and in all rural cohorts, girls obtained less schooling than boys. This disadvantage, however, has disappeared across cohorts in urban areas and diminished over time in rural ones. Similarly, disadvantages associated with being the oldest child also diminished and disappeared across cohorts. These results highlight the Indonesian government’s success in expanding schooling opportunities, especially for girls. The speed with which sex and birth order differences in schooling have narrowed reflects Indonesia’s relatively egalitarian family organization, at least relative to other East Asian countries.

Standard analyses of the relationship between family size and children’s schooling make strong assumptions about the relationship between family size and parents’ preferences for children’s schooling. Although IV analysis requires its own set of strong assumptions, the results presented here suggest that, at least in the most recent urban cohorts, the negative relationship between family size and children’s schooling is not sensitive to assumptions about the exogeneity of fertility. Ideally, one would confirm this result by using other instruments, such as twins, but household surveys like the IFLS do not have large enough samples to support this type of analysis, especially for a cohort design like the one used here. Recent studies using twin data from developed countries found no relationship between family size and children’s schooling once these variables were modeled jointly. Rosenzweig and Wolpin (1980a), in contrast, found a negative relationship using data from India, and Qian (2005) found mixed results using data from China. Few other studies have explored this question in a developing setting.

This pattern of associations changing from positive to neutral to negative in urban areas suggests that changes in socioeconomic and demographic conditions brought by development can alter the ways in which families benefit or impinge on children. Differences between more socioeconomically developed urban areas and less developed rural ones provide additional support for this explanation. The contrast between urban and rural areas, for example, serves as another measure of differences in transportation and communication infrastructure, school opportunities, and labor market opportunities.

Although testing specific mechanisms explaining this changing relationship is beyond the scope of the current study (and the data are limited in this regard), rapid development in Indonesia has changed numerous aspects of the economy, family organization, and educational opportunities, offering some candidate explanations for the patterns shown above. For the oldest urban cohort, it seems likely that widely shared preferences for larger families combined with better family resources, such as education and occupation and much better accessibility of schools, offered those in urban areas the ability both to have more children and to provide those children with some schooling. Moreover, in this older cohort, average attainments were still relatively low such that the cost of schooling itself was low. It also seems likely that schooling offered better payoffs for urban residents than for the largely agrarian-based residents of rural areas.

Between 1970 and 1980, primary schooling became nearly universal in urban areas and grew by nearly 30 percentage points in rural areas (Oey-Gardiner 1997). Given this infusion of schooling at the primary level, it seems likely that families’ educational aspirations grew. But the expansion in educational infrastructure was substantially slower at the secondary level. The per-student cost of secondary schooling remains about 3 times that of primary schooling, while the per-student cost of tertiary schooling is about 13 times as high (UNESCO 1999). Parents, rather than other family members or broader kin, pay the family’s portion of these costs, which can be sizeable especially for poorer families. Even before the economic crisis of 1997–1998 (an experience that affected subsequent waves of the IFLS but not the samples used here), Indonesia could not finance the expansion in post-primary schooling that the nation hoped to achieve (World Bank 1998). As the educational distribution continues to shift upward, parents with more children may be unable to afford the cost of postprimary schooling, at least for some of their children. At the same time, changing norms about schooling girls increases the number of children families may want to educate relative to older cohorts.

Differences between urban and rural areas might be explained by several factors. Before the 1970s, parents in rural areas had limited options for schooling children. As Lloyd (1994:9) argued, some threshold level of development is necessary before family size can even influence children’s schooling. In an area with no schools, having many or few siblings is irrelevant for children’s schooling. Also, the local agrarian economy meant that the returns to schooling were likely low relative to those living in urban areas. In more recent years, primary schooling has become widely available, free, and compulsory. Although most children now complete primary school, the education distribution in rural areas has yet to shift up to the more expensive secondary level. It remains an open question whether higher schooling costs, changing labor market conditions, change or stability in family organization, and growing migration rates will produce similar or different patterns in rural areas in the future.

These results and candidate explanations are not meant to argue that socioeconomic development inevitably produces family and school patterns that are negatively correlated, whether causally or because those who value education highly will have fewer children. Indeed, one of the most important lessons of this literature has been that patterns differ greatly by context. These results instead speak to the diversity of possible relationships and to the interplay of macro socioeconomic factors, government policies, norms and preferences, and familial and local mechanisms in producing patterns of stratification by place and family structure.

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Health & Society Scholars program for their financial support. I owe many thanks to Elizabeth Frankenberg, Jinyong Han, Robert Mare, William Mason, Douglas McKee, Judith Seltzer, Duncan Thomas, Donald Treiman, and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and advice.

Footnotes

The competing “confluence theory” suggests that additional children lower a family’s average intellectual environment, leaving children in larger sibships and those with higher birth order worse off (Zajonc and Markus 1975). Empirical analyses, however, have not found much support for this theory (Hauser and Sewell 1985; Retherford and Sewell 1991).

Except for Angrist et al. (2006), all of these studies assumed that fertility is exogenous to children’s schooling.

See Preston (1976) for a precise demonstration of the relationship between the average number of children ever born for a cohort of women and the average sibship size of the offspring of those women.

I use the terms sibship size and family size interchangeably. These terms mean all of a child’s brothers and sisters plus the child himself/herself. When I count a child’s siblings, I use the sibship size minus one.

About two-thirds of Indonesia’s total population and 70% of its urban population reside on Java. Java and the outer islands have a mix of urban and rural populations, although the proportion urban differs across islands. In the 1990s, Java was about 40% urban compared with an average of 26% for the other areas (Firman 1997).

About 7% of those in the 1968–1977 cohort were enrolled in school in 1997 (concentrated at ages 20 to 23). More than 90% of these respondents had completed grade 12 or higher, with a median and mode of 15 years of schooling. Therefore, nearly all are assigned to the highest education category despite their censored schooling.

I am grateful to Duncan Thomas for letting me borrow his coding of the IFLS household expenditure data for these sensitivity tests. An appendix describing these sensitivity tests is available from the author.

See Downey et al. (1999), Guo and VanWey (1999a), and Phillips (1999) for a discussion of the relative merits of Guo and VanWey’s approach.

Rosenzweig and Wolpin (2000) have provided an excellent discussion of the limitations of using twins as instruments. Rosenzweig and Wolpin (1980a) pointed out that there are biological differences between twins themselves, and between twins and nontwins. Twins have substantially lower gestational age, lower birth weight, and more complicated deliveries. Twins might therefore be less healthy, on average, than singletons. And while twinning might represent the addition of an extra child in the short term, it is not equivalent to adding an additional child to a woman’s completed fertility. The evidence shows that women adjust their subsequent fertility to compensate for the unexpected extra child. The completed fertility of women who have twins is substantially less than an average of one child higher, and this difference has been declining over time and varies between groups (Bronars and Grogger 1994; Jacobsen, Pearce, and Rosenbloom 1999).

Means for the most recent cohort (1978–1981) are not directly comparable to the other three cohorts because schooling and family size are not completed for this younger group.

Because schooling is censored for this cohort, it is impossible to know whether the gender gap will remain closed once this cohort completes its schooling. If boys have higher continuation probabilities into the higher levels of schooling, which the data suggest is still true for this recent IFLS cohort, then a small gender gap favoring boys may emerge by the time the cohort completes its schooling.

About 7% of those in the 1968–1977 cohort are still enrolled in school, and it is likely that average attainment in the top decile will be higher than shown once their schooling is completed.

None of the means for the 1968–1977 rural cohort are significantly different from each other. In all other cohorts, the mean for the 7+ category is significantly different from the mean for the 0–2 and 3–4 categories. The means for the 0–2 and 3–4 categories are not significantly different.

The results shown in Tables 3 and 4 assume that fertility and children’s schooling are not jointly determined.

The remainder of the analysis focuses on the additive effects of family size on children’s schooling both to draw out the major contours of these relationships across cohorts and to provide tractable models for the instrumental variables analysis. This simplification ignores two interactions that are descriptively interesting but do not change the substantive patterns shown here. First, in all three urban cohorts, the effect of family size is diminished or made more negative when fathers are highly educated. This interaction is not significant in the first two rural cohorts and is marginally significant in the 1968–1977 rural cohort. Second, in some cohorts, fathers with more schooling provide an extra boost to their daughters’ education. Other interactions, such as family size by the sex of the index child or family size by mother’s schooling, show no meaningful patterns across cohorts.

Overall, however, this association should be interpreted cautiously. Children in the most recent cohort are more likely to have siblings who survive and who are captured in the survey. Therefore, children identified as the “oldest” in these cohorts are less likely to be positively selected than those identified as the oldest child in the oldest urban cohort (1948–1957) when both mothers and children were older and mortality rates were higher.

In a joint model, the two-way interactions of family size and cohort and rural status and cohort are significant. The two-way interaction of siblings and rural status is not significant. The three-way interaction of family size, cohort, and rural status is also not significant (models not shown).

Only 4% of children ages 7 to 19 worked while enrolled in school, with the proportions slightly higher in rural than in urban areas (4.7% versus 2.3%).

These samples and transitions are not conditioned on completing at least grade 8 or 9. Results do not change if the sample is restricted to only those who made the previous transitions.

The sibling categories in Models 4.4 and 4.8 are not jointly significantly different from zero.

About three-fourths of women in the IFLS sample reported no miscarriages. At the high end, about 7% reported that more than 20% of their total number of pregnancies ended in miscarriage. A possible confounding factor is if women report abortions, which are legally prohibited in Indonesia except to save a woman’s life, as miscarriages. Women who miscarry may also try to compensate for this lost fertility or treat the children they do have differently than women who never miscarry. Recall error is another important problem that I discuss in more detail later.

There is no evidence that the risk of miscarriage increases with pregnancy number (Kline et al. 1989; Leridon 1976). Indeed, in this sample, the average proportion of pregnancies ending in miscarriage is similar across different family sizes. Also, the number of living siblings is correlated but not collinear with either miscarriages or the proportion of pregnancies that end in miscarriage (ρ = .13 and –.02 respectively). In this sample, women’s education is weakly positively correlated with miscarriages (ρ = .14), and this variable is controlled in all models. Although using whether a woman’s first birth resulted in a miscarriage would be an even better IV strategy (Rosenzweig and Wolpin 2000), the IFLS sample is too small to support this approach, especially for older cohorts.

The exogenous OLS results corresponding to the ordered probit analyses shown in Table 3 and the full set of IV results are omitted due to space limitations. These are available from the author as an appendix.

REFERENCES

- Angrist JD, Evans WN. “Children and Their Parents’ Labor Supply: Evidence From Exogenous Variation in Family Size”. American Economic Review. 1998;88:450–77. [Google Scholar]

- Angrist JD, Lavy V, Schlosser A.2006“Multiple Experiments for the Causal Link Between the Quantity and Quality of Children.”Working Paper 06-26. Department of Economics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Available online at http://ssrn.com/abstract=931948