Abstract

Background

Hyperhomocysteinemia is a cardiovascular risk factor that is associated with the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA). Using mice transgenic for overexpression of the ADMA-hydrolyzing enzyme dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase-1 (DDAH1), we tested the hypothesis that overexpression of DDAH1 protects from adverse structural and functional changes in cerebral arterioles in hyperhomocysteinemia.

Methods and Results

Hyperhomocysteinemia was induced in DDAH1 transgenic (DDAH1 Tg) mice and wild-type littermates using a high methionine/low folate (HM/LF) diet. Plasma total homocysteine was elevated approximately 3-fold in both wild-type and DDAH1 Tg mice fed the HM/LF diet compared with the control diet (P<0.001). Plasma ADMA was approximately 40% lower in DDAH1 Tg mice compared with wild-type mice (P<0.001) irrespective of diet. Compared with the control diet, the HM/LF diet diminished endothelium-dependent dilation to 10 µmol/L acetylcholine in cerebral arterioles of both wild-type (12±2 vs. 29±3%; P<0.001) and DDAH1 Tg (14±3 vs. 28±2%; P<0.001) mice. Responses to 10 µmol/L papaverine, a direct smooth muscle dilator, were impaired with the HM/LF diet in wild-type mice (30±3 vs. 45±5%; P<0.05) but not DDAH1 Tg mice (45±7 vs. 48±6%). DDAH1 Tg mice also were protected from hypertrophy of cerebral arterioles (P<0.05) but not from accelerated carotid artery thrombosis induced by the HM/LF diet.

Conclusions

Overexpression of DDAH1 protects from hyperhomocysteinemia-induced alterations in cerebral arteriolar structure and vascular muscle function.

Keywords: amino acids, nitric oxide synthase, endothelium, vasodilation, thrombosis

Introduction

Hyperhomocysteinemia is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, ischemic stroke, and venous thromboembolism.1, 2 Abnormal vasomotor function, altered vascular mechanics and morphology, and accelerated thrombosis have been observed in animal models of hyperhomocysteinemia.3 Although there is strong epidemiological evidence that hyperhomocysteinemia is associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events, several large intervention trials have failed to demonstrate any clinical benefit of homocysteine-lowering therapy.4–9 The negative results of these trials may be related to inadequate sample size, confounding due to effects of folate fortification, or possible adverse effects of high dose B vitamins.10 Another possible explanation is that hyperhomocysteinemia might be associated with increased cardiovascular risk because it is a marker of another causative risk factor. One candidate for such a factor is asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide (NO) synthase.10

Dysregulation of ADMA metabolism may occur in hyperhomocysteinemia through an inhibitory effect of homocysteine on the expression and activity of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH), which hydrolyzes ADMA to citrulline and dimethylamine.11–13 Overexpression of the major isoform of DDAH, DDAH1, in transgenic mice has been shown to protect from the adverse vasomotor effects of exogenous ADMA on endothelial function. 14, 15 It is not known, however, if DDAH1 overexpression protects from the vascular consequences of hyperhomocysteinemia. Interestingly, DDAH also may influence vascular function through a mechanism that is independent of ADMA hydrolysis.16, 17 The ADMA-independent cellular effects of DDAH are thought to involve direct binding of DDAH to cell signaling molecules such as protein kinase A or Ras pathway regulatory molecules.18

The goal of the present study was to utilize DDAH1 transgenic mice to test the hypothesis that overexpression of DDAH1 protects from hyperhomocysteinemia-induced vascular dysfunction, vascular hypertrophy, and thrombosis. Our findings demonstrate that transgenic overexpression of DDAH1 does not protect mice with dietary hyperhomocysteinemia from endothelial dysfunction or accelerated thrombosis. In contrast, overexpression of DDAH1 does provide protection from the deleterious effects of hyperhomocysteinemia on vascular muscle function and the development of cerebral vascular hypertrophy. A lack of elevation of plasma ADMA in hyperhomocysteinemic mice suggests that these protective effects of DDAH1 may be independent of ADMA.

Methods

Mice and experimental diets

Animal protocols were approved by the University of Iowa and Veterans Affairs Animal Care and Use Committees. Human DDAH1 transgenic (DDAH Tg) mice14 were generated on the C57BL/6 background and maintained by backcrossing to C57BL/6 mice. Genotyping was performed by polymerase chain reaction using the primers: 5’ – AGCACCAGCTCTACGTG – 3’ (forward) and 5’- GCCCTTTGTTGGGGATATT-3’ (reverse). Starting from the time of weaning (3–4 weeks of age), mice were fed either a control diet (LM485, Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI), which contains 6.7 mg/Kg folic acid and 4.0 g/Kg L-methionine, or a high methionine/low folate (HM/LF) diet (TD00205, Harlan Teklad) that contains 0.2 mg/Kg folic acid and 8.2 g/Kg of L-methionine.19 Mice were maintained on the control or HM/LF diets until they were studied at 6–12 months of age.

Plasma total homocysteine, ADMA, and SDMA

Blood was collected by cardiac puncture into EDTA (final concentration 5 mmol/L). Plasma was separated by centrifugation, flash frozen, and stored at −80°C. Plasma total homocysteine (tHcy), defined as the total concentration of homocysteine after quantitative reductive cleavage of all disulfide bonds,20 was measured by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using ammonium 7-fluorobenzo-2-oxa-1,3-diazole-4-sulphonate fluorescence detection.21 Plasma and tissue levels of ADMA and SDMA were determined by HPLC using precolumn derivatization with o-phthaldialdehyde.22

Immunoblotting

Samples of aorta or carotid artery were homogenized in ice-cold HEMGN buffer (25 mmol/L HEPES [pH 7.6], 0.1 mmol/L EDTA, 12.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 100 mmol/L KCl, 10% glycerol [v/v], 0.1% NP-40 [v/v]) containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete™ Mini EDTA-free, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Homogenates were centrifuged at 14000 × g for 30 minutes at 4°C. Protein concentrations of supernatant fractions were determined using the Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Samples (5 µg protein) were separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% polyacrylamide gels, transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA), and probed with 1 µg/ml monoclonal antibody raised against rat DDAH123 for 2 hours at room temperature. This antibody cross-reacts with both murine and human DDAH1.15 To control for sample loading, the membranes were reprobed with 0.5 µg/ml anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) for 2 hours at room temperature. HRP-conjugated goat-antimouse antibody (Pierce, Rockford, IL,) was used as the secondary antibody (10 ng/ml, 1 hour, RT). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using Supersignal West Femto (Pierce, Rockford, IL) detection system. Densitometry was performed on a BioRad VersaDoc Imaging System equipped with the Quantity1 software program.

Vasomotor function in cerebral arterioles

Dilation of cerebral arterioles was measured using a cranial window preparation as described previously.24 Briefly, mice were anesthetized and ventilated mechanically with room air and supplemental oxygen, a cranial window was made over the left parietal cortex, and a segment of a randomly selected pial arteriole (about 30 µm in diameter) was exposed. Changes in the diameter of the cerebral arteriole were measured, using a video microscope coupled to an image-shearing device, during superfusion with acetylcholine (1 and 10 µmol/L) and papaverine (1 and 10 µmol/L).

Structure and mechanics of cerebral arterioles

Systemic arterial blood pressure was measured in conscious mice using a carotid artery catheter as described previously.25 Pressure and diameter in first order arterioles on the cerebrum were measured in anesthetized mice through an open skull preparation with a micropipette connected to a servo-null pressure-measuring device as described previously.26 Arteriolar pressures and diameter were measured under baseline conditions and again after deactivation of vascular muscle by suffusion of cerebral vessels with artificial CSF containing EDTA as described previously.26 After the animal was killed by an injection of potassium chloride, the arteriolar segment used for pressure-diameter measurements was removed, processed and embedded for microscopy in Spurr’s low viscosity resin while maintaining crosssectional orientation. The cross-sectional area (CSA) of the arteriolar wall was determined as described in the online supplement. Mechanical characteristics of cerebral arterioles (circumferential stress, circumferential strain and tangential elastic modulus) were calculated from measurements of cerebral arteriolar pressure, diameter and cross-sectional area using an approach we have described in detail previously.26, 27

Carotid artery thrombosis

Carotid artery thrombosis was induced by photochemical injury as described previously.28 Mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (70–90 mg/kg intraperitoneally) and ventilated mechanically with room air and supplemental oxygen. The left femoral vein was cannulated for the administration of rose bengal. The right common carotid artery was dissected free and carotid artery blood flow was measured with a 0.5 PSB Doppler flow probe (Transonic Systems, Inc., Ithaca, NY) and digital recording system (Gould Ponemah Physiology Platform version 3.33). To induce endothelial injury, the right common carotid artery was transilluminated continuously with a 1.5-mV, 540-nm green laser (Melles Griot, Carlsbad, CA) from a distance of 6 cm, and rose bengal (35 mg/kg) was injected via a femoral vein catheter. Blood flow was monitored continuously for 90 minutes or until stable occlusion occurred, at which time the experiment was terminated. First occlusion was defined as the time at which blood flow first decreased to zero for ≥ 10 seconds, and stable occlusion was defined as the time at which blood flow remained absent for ≥ 10 minutes.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of effects of genotype and diet on plasma metabolites and vascular mechanics (arteriolar pressures, diameters, cross-sectional area, wall thickness, and slope of tangential elastic modulus versus stress) were performed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Holm-Sidak posthoc test for multiple comparisons. Responses of cerebral arterioles to vasodilators were analyzed using two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Holm-Sidak posthoc analysis. Effects of genotype and diet on carotid artery thrombosis were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with log-rank testing. Statistical significance was defined as a P value <0.05. Values are reported as mean±SE.

Results

Plasma tHcy and ADMA in DDAH1 transgenic mice

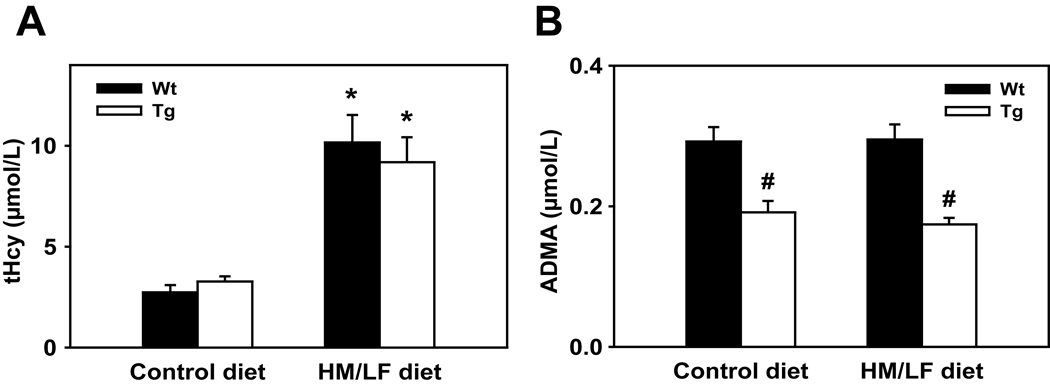

To determine if overexpression of DDAH1 can protect from deleterious vascular effects of homocysteine in vivo, we used a HM/LF diet to induce dietary hyperhomocysteinemia in DDAH1 Tg mice and wild-type littermates. Plasma tHcy was elevated approximately 3-fold in both wild-type and DDAH1 Tg mice fed the HM/LF diet compared with the control diet (P<0.001) (Figure 1A). Plasma tHcy did not differ between wild-type and DDAH1 Tg mice. Plasma ADMA was similar in wild-type mice fed the control (0.29±0.02 µmol/L) and HM/LF (0.30±0.02 µmol/L) diets (Figure 1B), but was approximately 40% lower in DDAH1 Tg mice fed either diet (P<0.001) (Figure 1B). There were no statistically significant differences in SDMA levels between the groups (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Plasma levels of (A) tHcy and (B) ADMA in wild-type and DDAH1 Tg mice fed either the control diet or the HM/LF diet. Filled bars indicate wild-type mice and open bars indicate DDAH1 Tg mice. Values are mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 compared with mice of the same genotype fed the control diet. #P<0.05 compared with wild-type mice fed the same diet (n=8 in each group).

Expression of DDAH1 in aorta and carotid arteries

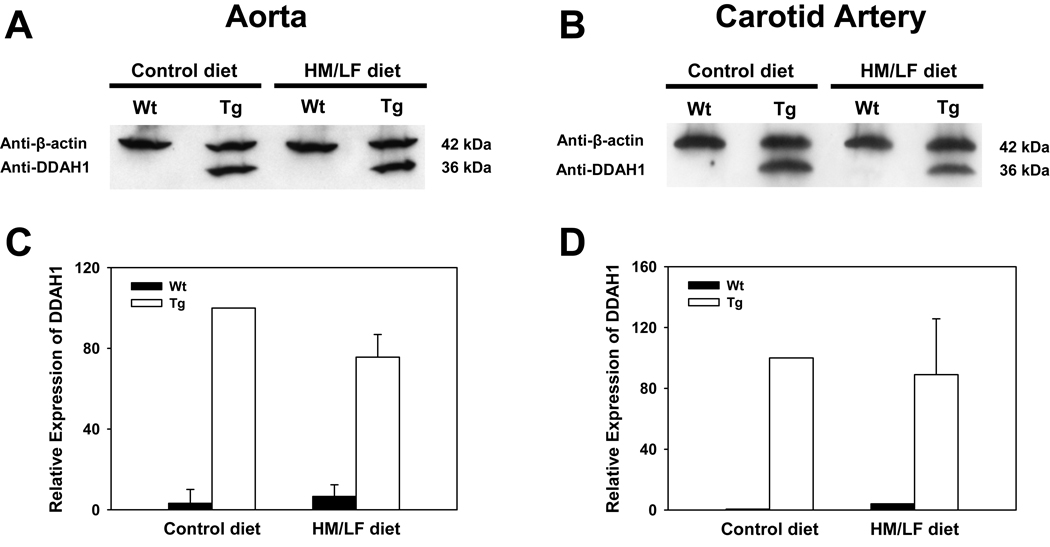

Expression of DDAH1 protein was detected by immunoblotting in both the aorta and carotid artery of DDAH1 Tg mice (Figure 2). No expression of DDAH1 protein was detected in the aorta or carotid artery of wild-type mice. The expression of DDAH1 was not significantly affected by the dietary intervention (P=0.14).

Figure 2.

Representative immunoblots for DDAH1 and β-actin in (A) aorta and (B) carotid artery from wild-type (Wt) or DDAH1 Tg (Tg) mice fed the control or HM/LF diets. Densitometric analysis of DDAH1 expression, normalized to β-actin and expressed relative to Tg mice fed the control diet is shown for the aorta (C) (n=5) and for pooled samples of carotid artery (n=2 with 3 mice in each pool).

Vascular function in cerebral arterioles

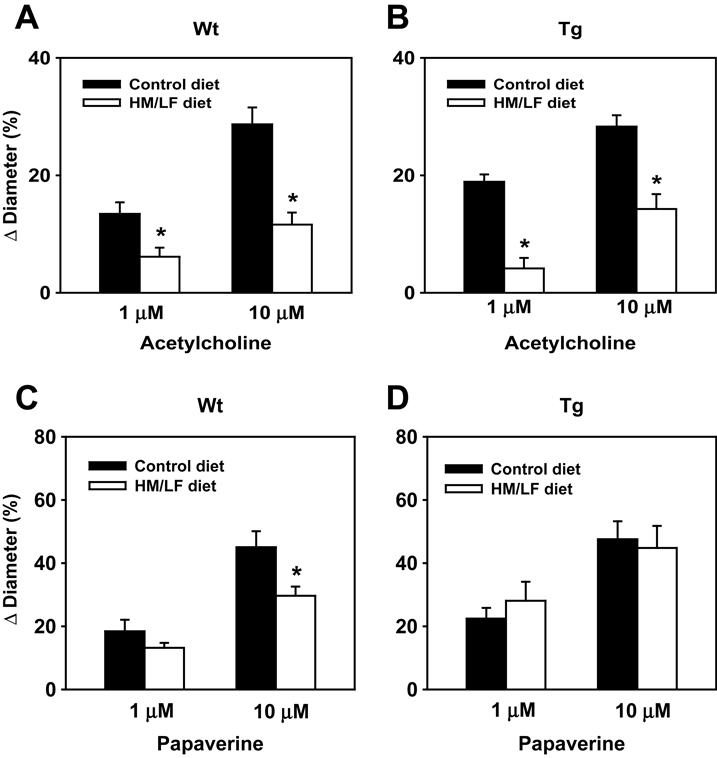

Dilation of cerebral arterioles in response to the endothelium-dependent dilator, acetylcholine, was impaired in wild-type mice fed the HM/LF diet compared with the control diet (Figure 3A). A similar degree of impairment in dilator responses to acetylcholine was seen in DDAH1 Tg mice fed the HM/LF diet compared with the control diet (Figure 3B). Compared with the control diet, the HM/LF diet diminished dilator responses to 10 µmol/L acetylcholine by 60% in wild-type mice (12±2 vs. 29±3%; P<0.001) and 50% in DDAH1 Tg (14±3 vs. 28±2%; P<0.001).

Figure 3.

Vasomotor function in cerebral arterioles. Dilation of cerebral arterioles to acetylcholine (A, B) or papaverine (C, D) in wild-type (A, C) and DDAH1 Tg (B, D) mice. Filled bars indicate mice fed the control diet and open bars indicate mice fed the HM/LF diet. Values are mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 compared with mice of the same genotype fed the control diet (n=7–14 in each group).

Cerebral arteriole responses to the direct smooth muscle agonist, papaverine (Figure 3C and 3D) were also similar between wild-type and DDAH1 Tg mice fed the control diet. However, responses to the highest doses of papaverine (10 µmol/L) were lower in wild-type mice fed the HM/LF diet than in wild-type mice fed the control diet (30±3 vs. 45±5%; P<0.05). Responses to papaverine did not differ between the control diet and the HM/LF diet in DDAH1 Tg mice (Figure 3D and 3F).

Morphological and mechanical properties of cerebral arterioles

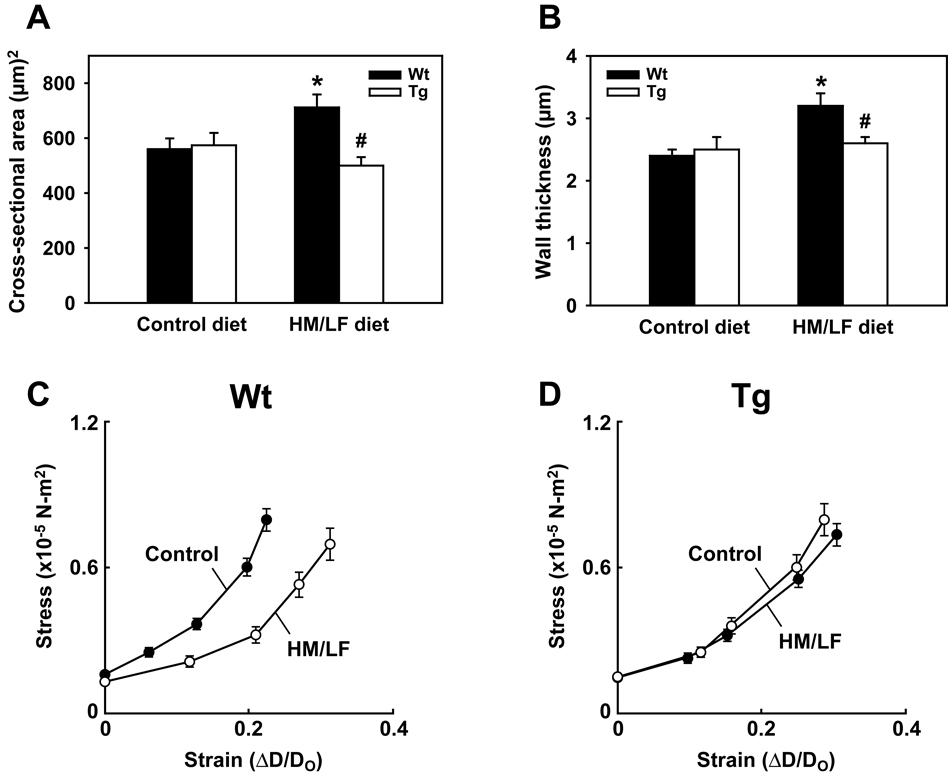

The relative preservation of responses to the endothelium-independent vasodilator papaverine in DDAH1 Tg mice fed the HM/LF diet suggested a possible protective effect of DDAH1 on the structural mechanics of the vessel wall. To determine if overexpression of DDAH1 protects from hyperhomocysteinemia-induced alterations in cerebral arteriole structure and elasticity,26 wild-type and DDAH1 Tg mice were fed the control or HM/LF diets for 8 to 12 months. Systemic arterial mean pressure did not differ between groups of mice in either the unanesthetized or anesthetized states (Table 1). Cerebral arteriolar pressures and diameters also did not differ significantly between groups of anesthetized mice (Table 1). The cross-sectional area of the vessel wall was significantly increased in cerebral arterioles of wild-type mice fed the HM/LF diet compared with the control diet (Table 1 and Figure 4A). Wall thickness was also significantly increased in these mice (Table 1 and Figure 4B). In striking contrast, no increases in cross-sectional area or wall thickness were observed in DDAH1 Tg mice fed the HM/LF diet compared with the control diet. The slope of tangential elastic modulus versus stress was decreased (Table 1) and stress-strain curves were shifted to the right (Figure 4C) in cerebral arterioles of wild-type mice fed the HM/LF diet compared with the control diet (Table 1). These results, which reflect an increase in passive distensibility, are consistent with previous findings in cerebral arterioles of hyperhomocysteinemic mice.26 Interestingly, the stress-strain curves of the cerebral arterioles of DDAH1 Tg mice did not differ between the control and HM/LF diets (Figure 4D). The slope of tangential elastic modulus and stress in both groups of DDAH1 Tg mice was significantly higher than that in wild-type mice fed the HM/LF diet (Table 1).

Table1.

Effect of diet and genotype on vascular parameters.

| Parameter | Wild-type | DDAH 1 Tg | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control diet | HM/LF diet | Control diet | HM/LF diet | |

| Prior to Maximal Dilatation | ||||

| Systemic Arterial Mean Pressure (mm Hg) | ||||

| Unanesthetized | 126±2 | 128±3 | 126±2 | 132±3 |

| Anesthetized | 62±2 | 63±1 | 62±2 | 65±3 |

| Cerebral Arteriolar Pressure (mm Hg) | ||||

| Systolic | 46±2 | 48±2 | 47±2 | 50±2 |

| Diastolic | 31±2 | 33±1 | 33±1 | 34±2 |

| Mean | 36±2 | 38±1 | 38±1 | 39±2 |

| Pulse | 15±1 | 15±2 | 14±1 | 16±1 |

| Arterial Blood Gases | ||||

| pCO2 | 34±4 | 32±3 | 34±2 | 32±3 |

| pH | 7.38±0.03 | 7.34±0.03 | 7.36±0.01 | 7.33±0.02 |

| pO2 | 112±5 | 118±6 | 113±3 | 112±7 |

| Internal Cerebral Arteriolar Diameter (µm) | 49±2 | 50±4 | 48±4 | 43±3 |

| After Maximal Dilatation | ||||

| Cerebral Arteriolar Diameter (µm) | ||||

| Internal | 69±2 | 68±5 | 66±4 | 62±5 |

| External | 75±2 | 75±4 | 72±4 | 67±4 |

| Cross-sectional Area of Vessel Wall (µm2) | 560±39 | 712±47* | 574±45 | 500±31† |

| Wall Thickness (µm) | 2.4±0.1 | 3.2±0.2* | 2.5±0.2 | 2.6±0.1† |

| ET vs Stress | 7.27±0.55 | 5.21±0.32* | 5.91±0.58 | 5.82±0.37† |

| N | 9 | 11 | 10 | 11 |

Measurements of internal diameter prior to maximal dilatation of cerebral arterioles were obtained at prevailing levels of arterial pressure. Measurements of internal diameter after maximal dilatation were made at an arteriolar mean pressure of 40 mmHg. Values of external diameter after maximal dilatation were calculated from measurements of internal diameter at 40 mm Hg arteriolar pressure and histological measurements of cross-sectional area of the vessel wall. ET vs Stress: slope of tangential elastic modulus (ET) versus stress. Values are mean ± SEM.

P<0.05 vs. wild-type mice fed the control diet;

P<0.05 vs. wild-type mice fed the HM/LF diet.

Figure 4.

Morphological and mechanical properties of cerebral arterioles. Cross-sectional area (A) and wall thickness (B) of cerebral arterioles in wild-type and DDAH1 Tg mice. Filled bars indicate wild-type mice and open bars indicate DDAH1 Tg mice. Values are mean ± SEM. *P<0.05 compared with wild-type mice fed the control diet. #P<0.05 compared with wild-type mice fed the HM/LF diet. Circumferential stress vs. strain in wild-type (C) or DDAH1 Tg (D) mice in fed either the control diet (solid symbols) or HM/LF (open symbols) diet (n=9–11 in each group).

Carotid artery thrombosis

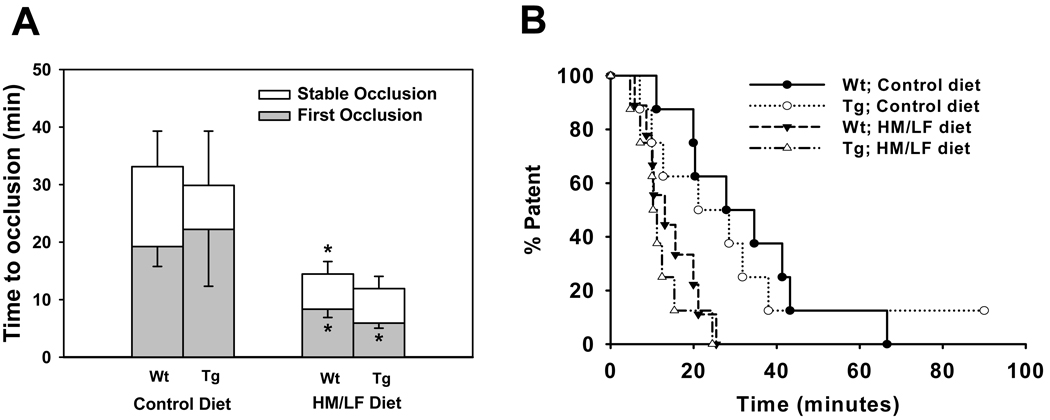

Susceptibility to carotid artery thrombosis was assessed using a photochemical injury method.28 The mean times to first occlusion or stable occlusion did not differ significantly between wild-type and DDAH1 Tg mice fed the control diet (Figure 5A). The HM/LF diet caused a 60–70% shortening of the mean times to first occlusion and stable occlusion independently of genotype. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis demonstrated significant differences in carotid artery patency, defined as absence of stable occlusion, between mice fed the control and HM/LF diets (P<0.05 for either genotype), but no significant differences in patency between wild-type and DDAH1 Tg mice (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Carotid artery thrombosis after photochemical injury. (A) Time to first occlusion (filled bars) or stable occlusion (open bars) in wild-type or DDAH1 Tg mice fed either the control or HM/LF diets. Values are mean ± SE. *P<0.05 compared with mice of same genotype fed the control diet (n=8–9 in each group). (B) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of carotid artery patency, defined as absence of stable occlusion time as a function of time after administration of rose bengal, in wild-type mice fed the control diet (filled circles), DDAH1 Tg mice fed the control diet (open circles), wild-type mice fed the HM/LF diet (filled triangles), or DDAH1 Tg mice fed the HM/LF diet (open triangles).

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that overexpression of DDAH1 protects from the adverse vascular effects of hyperhomocysteinemia. There two major findings from this study: 1) Contrary to our hypothesis, we found that overexpression of DDAH1 did not protect from hyperhomocysteinemia-induced endothelial dysfunction or thrombosis despite causing a significant lowering of plasma ADMA. These findings suggest that, at least in this model, hyperhomocysteinemia impairs vascular endothelial function through a mechanism that is largely independent of the ADMA/DDAH pathway. It is more likely, therefore, that hyperhomocysteinemia produces endothelial dysfunction through alternative mechanisms, such as inhibition of endothelial NO synthase activity by protein kinase C29 or oxidative inactivation of NO caused by an impairment in cellular antioxidant enzyme activity.30 2) Although DDAH1 Tg mice were not protected from hyperhomocysteinemia-induced endothelial dysfunction, they did exhibit resistance to impairment of vascular responses to the endothelium-independent agonist, papaverine, and to alterations in cerebral vascular wall structure and mechanics. These findings suggest that DDAH1 selectively protects from the deleterious effects of hyperhomocysteinemia on vascular muscle. The lack of elevation of plasma ADMA in hyperhomocysteinemic mice suggests that these protective effects of DDAH1 may be independent of ADMA.

One potential limitation of our study is that the HM/LF diet did not cause an elevation of plasma ADMA. Similar observations have been made in other murine models of hyperhomocysteinemia,13, 29 raising the possibility that metabolic interactions between homocysteine and ADMA may differ in mice and humans. Even in humans, however, some recent studies have demonstrated that hyperhomocysteinemia is not always accompanied by elevation of plasma ADMA.31, 32 It is possible that ADMA may accumulate intracellularly and inhibit vascular function even in the absence of elevation of plasma ADMA, since ADMA is actively taken up by vascular cells.33 Another intriguing possibility is that the protective effects of DDAH1 overexpression that we observed may be ADMA-independent. Both DDAH1 and DDAH2 have been proposed to have effects on vascular cells that are independent of ADMA hydrolysis.16, 17, 34 Future studies with catalytically-inactive variants of DDAH could be designed to address the role of the ADMA-independent effects of DDAH in the regulation of vascular function.

In agreement with previous studies of diet-induced hyperhomocysteinemia in mice,19 plasma levels of tHcy were about 3-fold higher in both wild-type and DDAH1 Tg mice fed the HM/LF diet compared with mice fed the control diet. Because hyperhomocysteinemia can lead to a decrease in the expression and activity of endogenous DDAH1,11, 13 it was essential to demonstrate that the HM/LF diet did not alter the expression or activity of the DDAH1 transgene. Immunoblotting showed that expression of the human DDAH1 transgene under the control of the β-actin promotor was not significantly affected by the HM/LF diet, and overexpression of the DDAH1 transgene lowered plasma ADMA to a similar extent in DDAH1 Tg mice fed the control and HM/LF diets. These findings suggest that the expression and activity of the transgene was similar in normohomocysteinemic and hyperhomocysteinemic mice.

Several previous studies by our group and others have demonstrated that hyperhomocysteinemic animals have impaired vasomotor responses to endothelium-dependent dilators.35 In some animal models, including the primate model in which we first demonstrated vasomotor dysfunction in mild hyperhomocysteinemia,36 impaired responses to endothelium-independent vasodilators also have been observed. In murine models of hyperhomocysteinemia, responses to endothelium-dependent dilators first become impaired in young mice (less than 6 months of age).35 In older mice (greater than 6 months of age), impaired responses to both endothelium-dependent dilators and endothelium-independent dilators are often observed.37 The current results, in which the HM/LF diet produced impairment of responses in cerebral arterioles to papaverine in wild-type mice aged 6–12 months (Figure 3), are consistent with these previous findings.

One potential mechanism of hyperhomocysteinemia-induced smooth muscle dysfunction is cerebral vascular hypertrophy,26 which can lead to impairment in maximal vasodilator capacity.38 To test the hypothesis that overexpression of DDAH1 protects from hyperhomocysteinemia-induced structural changes in vascular wall, we examined the wall thickness and cross-sectional area of cerebral arterioles in DDAH1 transgenic mice fed either the control or the HM/LF diet. Consistent with our previous observations,26 hyperhomocysteinemia induced hypertrophic changes in the arterial wall, with significant increases in both wall thickness and cross-sectional area (Figure 4). Like the effects of hyperhomocysteinemia on endothelium-independent vasomotor responses, vascular hypertrophy was prevented by overexpression of the DDAH1 transgene. It is very possible, therefore, that structural changes in the vessel wall are at least partially responsible for the observed impairment in response to papaverine.

Because the HM/LF diet did not elevate plasma ADMA, it is possible that the protective effect of DDAH1 on smooth muscle structure and function is independent of ADMA. One potential mechanism for this protective effect is the DDAH1-dependent phosphorylation of neurofibromin 1 (NF1).34 NF1 has been shown to regulate smooth muscle proliferation,39 so modulation of NF1 activity by DDAH1 could potentially affect vascular wall structure and function. Another possible mechanism is that, despite the lack of elevation of plasma ADMA, hyperhomocysteinemia may promote the accumulation of intracellular ADMA in vascular cells.40 If this is the case, then the protective effects of DDAH1 could be mediated by increased metabolism of this intracellular pool of ADMA. By decreasing intracellular levels of ADMA, DDAH1 may prevent angiotensin II-mediated smooth muscle hypertrophy,41 perhaps leading to improved smooth muscle vasodilatory function. This potential mechanism is supported by the observation that the angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonist valsartan protects from hyperhomocysteinemia-induced ventricular hypertrophy and vascular remodeling.42, 43

We also observed that DDAH1 overexpression altered the changes in vessel wall elasticity induced by the hyperhomocysteinemic diet. As expected,26 mice fed the HM/LF diet for 8–12 months exhibited increased passive distensibility of cerebral arterioles compared with control mice (Figure 4C). This difference between the HM/LF and control diets was not observed in DDAH1 Tg mice (Figure 4D). Interestingly, the elasticity of cerebral arterioles in DDAH1 Tg mice appeared to be intermediate between that of wild-type mice fed the control diet and wild-type mice fed the HM/FL diet (demonstrated by the differences in the slope of ET vs. Stress shown in Table 1).

Finally, we tested the hypothesis that overexpression of DDAH1 protects from hyperhomocysteinemia-induced acceleration of thrombosis. We observed accelerated thrombosis in wild-type mice fed the HM/LF diet (Figure 5A and 5B), but overexpression of DDAH1 did not protect from accelerated thrombosis caused by hyperhomocysteinemia. This finding indicates that, at least in this animal model, hyperhomocysteinemia likely causes accelerated thrombosis via an ADMA-independent mechanism. Our results are consistent with our previous observations that deficiency of endothelial NOS (Nos3) in mice does not lead to accelerated thrombosis.44 Taken together these studies suggest that deficient NO production is not a major mechanism for enhancement of thrombosis in carotid arteries in hyperhomocysteinemia. Possible alternative mechanisms of the prothrombotic effects of hyperhomocysteinemia include decreased tissue plasminogen activator binding to annexin A2, upregulation of tissue factor, or hyperactivation of platelets.3

In summary, we tested the role of DDAH1 in protecting from the adverse vascular effects of hyperhomocysteinemia. Our results suggest that the DDAH/ADMA pathway is not a major mediator of hyperhomocysteinemia-induced endothelial dysfunction or accelerated thrombosis, In contrast, overexpression of DDAH1 protects from hyperhomocysteinemia-induced impairment of smooth muscle structure and function. The lack of elevation of plasma ADMA in hyperhomocysteinemic mice suggests that these protective effects of DDAH1 may be ADMA-independent.

Novelty and Significance.

A high blood level of the amino acid homocysteine is an established risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), yet several large clinical trials have failed to demonstrate any cardiovascular benefit of homocysteine-lowering therapy. One potential explanation is that elevation of homocysteine might be a biomarker of another causative risk factor such as asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA). The goal of this study was to utilize a transgenic mouse model to determine if dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH), an enzyme that metabolizes ADMA, protects from the adverse vascular effects of elevated homocysteine. The most important finding of the study is that overexpression of DDAH protects from the deleterious effects of homocysteine on the structure and function of vascular muscle within the wall of cerebral blood vessels. Interestingly, ADMA was not elevated in mice with high levels of homocysteine, suggesting that some of the vasoprotection conferred by DDAH may be independent of ADMA. This work raises several questions for future research on the ADMA dependent and ADMA-independent vascular effects of DDAH, which may be a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of cardiovascular disease.

What is known

Homocysteine is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, yet homocysteine-lowering therapy does not improve clinical outcomes

Homocysteine might be a biomarker of another risk factor such as ADMA

ADMA levels are regulated by the enzyme DDAH

New information contributed by this study

Overexpression of DDAH protects from some of the deleterious vascular effects of homocysteine in a mouse model

The ADMA/DDAH metabolic pathway may be a promising therapeutic target in CVD

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Brett Wagner for technical assistance.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the Office of Research and Development, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Institutes of Health grants HL63943, NS24621, and CA98303, an American Heart Association predoctoral fellowship award (0515537Z), and the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (RS1-00183).

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ADMA

asymmetric dimethylarginine

- CSA

cross-sectional area

- DDAH

dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase

- HM/LF

high methionine/low folate

- NF1

neurofibromin 1

- NO

nitric oxide

- Tg

transgenic

- tHcy

total homocysteine

- Wt

wild-type

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Journal subject codes: [95] Endothelium/vascular type/nitric oxide, [47] Brain Circulation and Metabolism, [145] Genetically altered mice

Disclosures

Dr. Cooke is the inventor of patents owned by Stanford University for diagnostic and therapeutic applications of the NOS pathway from which he receives royalties.

References

- 1.Homocysteine Studies Collaboration. Homocysteine and risk of ischemic heart disease and stroke: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2002;288:2015–2022. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.16.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.den Heijer M, Lewington S, Clarke R. Homocysteine, MTHFR and risk of venous thrombosis: a meta-analysis of published epidemiological studies. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:292–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lentz SR. Mechanisms of homocysteine-induced atherothrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:1646–1654. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toole JF, Malinow MR, Chambless LE, Spence JD, Pettigrew LC, Howard VJ, Sides EG, Wang CH, Stampfer M. Lowering homocysteine in patients with ischemic stroke to prevent recurrent stroke, myocardial infarction, and death: the Vitamin Intervention for Stroke Prevention (VISP) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:565–575. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonaa KH, Njolstad I, Ueland PM, Schirmer H, Tverdal A, Steigen T, Wang H, Nordrehaug JE, Arnesen E, Rasmussen K. Homocysteine lowering and cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1578–1588. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lonn E, Yusuf S, Arnold MJ, Sheridan P, Pogue J, Micks M, McQueen MJ, Probstfield J, Fodor G, Held C, Genest J., Jr Homocysteine lowering with folic acid and B vitamins in vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1567–1577. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jamison RL, Hartigan P, Kaufman JS, Goldfarb DS, Warren SR, Guarino PD, Gaziano JM. Effect of homocysteine lowering on mortality and vascular disease in advanced chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298:1163–1170. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.10.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.den Heijer M, Willems HP, Blom HJ, Gerrits WB, Cattaneo M, Eichinger S, Rosendaal FR, Bos GM. Homocysteine lowering by B vitamins and the secondary prevention of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Blood. 2007;109:139–144. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-014654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albert CM, Cook NR, Gaziano JM, Zaharris E, MacFadyen J, Danielson E, Buring JE, Manson JE. Effect of folic acid and B vitamins on risk of cardiovascular events and total mortality among women at high risk for cardiovascular disease: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;299:2027–2036. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.17.2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodionov RN, Lentz SR. The homocysteine paradox. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1031–1033. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.164830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stuhlinger MC, Tsao PS, Her JH, Kimoto M, Balint RF, Cooke JP. Homocysteine impairs the nitric oxide synthase pathway: role of asymmetric dimethylarginine. Circulation. 2001;104:2569–2575. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.098514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frey D, Braun O, Briand C, Vasak M, Grutter MG. Structure of the mammalian NOS regulator dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase: A basis for the design of specific inhibitors. Structure. 2006;14:901–911. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dayal S, Rodionov RN, Arning E, Bottiglieri T, Kimoto M, Murry DJ, Cooke JP, Faraci FM, Lentz SR. Tissue-specific downregulation of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase in hyperhomocysteinemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H816–H825. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01348.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dayoub H, Achan V, Adimoolam S, Jacobi J, Stuehlinger MC, Wang BY, Tsao PS, Kimoto M, Vallance P, Patterson AJ, Cooke JP. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase regulates nitric oxide synthesis: genetic and physiological evidence. Circulation. 2003;108:3042–3047. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000101924.04515.2E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dayoub H, Rodionov R, Lynch C, Cooke JP, Arning E, Bottiglieri T, Lentz SR, Faraci FM. Overexpression of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase inhibits asymmetric dimethylarginine-induced endothelial dysfunction in the cerebral circulation. Stroke. 2008;39:180–184. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.490631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pope AJ, Karuppiah K, Kearns PN, Xia Y, Cardounel AJ. Role of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolases in the regulation of endothelial nitric oxide production. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.037036. (Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hasegawa K, Wakino S, Tanaka T, Kimoto M, Tatematsu S, Kanda T, Yoshioka K, Homma K, Sugano N, Kurabayashi M, Saruta T, Hayashi K. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 2 increases vascular endothelial growth factor expression through Sp1 transcription factor in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1488–1494. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000219615.88323.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leiper J, Vallance P. New tricks from an old dog: nitric oxide-independent effects of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1419–1420. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000229598.55602.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devlin AM, Arning E, Bottiglieri T, Faraci FM, Rozen R, Lentz SR. Effect of Mthfr genotype on diet-induced hyperhomocysteinemia and vascular function in mice. Blood. 2004;103:2624–2629. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mudd SH, Finkelstein JD, Refsum H, Ueland PM, Malinow MR, Lentz SR, Jacobsen DW, Brattströ m L, Wilcken B, Wilcken DEL, Blom HJ, Stabler SP, Allen RH, Selhub J, Rosenberg IH. Homocysteine and its disulfide derivatives: a suggested consensus terminology. Arterioscl Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1704–1706. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.7.1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin SC, Hilton AC, Bartlett WA, Jones AF. Plasma total homocysteine measurement by ion-paired reversed-phase HPLC with electrochemical detection. Biomed Chromatogr. 1999;13:81–82. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0801(199902)13:1<81::AID-BMC762>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teerlink T, Nijveldt RJ, de JS, van Leeuwen PA. Determination of arginine, asymmetric dimethylarginine, and symmetric dimethylarginine in human plasma and other biological samples by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem. 2002;303:131–137. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimoto M, Whitley GS, Tsuji H, Ogawa T. Detection of NG,NG-dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase in human tissues using a monoclonal antibody. J Biochem. 1995;117:237–238. doi: 10.1093/jb/117.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dayal S, Arning E, Bottiglieri T, Böger RH, Sigmund CD, Faraci FM, Lentz SR. Cerebral vascular dysfunction mediated by superoxide in hyperhomocysteinemic mice. Stroke. 2004;35:1957–1962. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000131749.81508.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merrill DC, Thompson MW, Carney CL, Granwehr BP, Schlager G, Robillard JE, Sigmund CD. Chronic hypertension and altered baroreflex responses in transgenic mice containing the human renin and human angiotensinogen genes. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1047–1055. doi: 10.1172/JCI118497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baumbach GL, Sigmund CD, Bottiglieri T, Lentz SR. Structure of cerebral arterioles in cystathionine beta-synthase-deficient mice. Circ Res. 2002;91:931–937. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000041408.64867.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baumbach GL, Siems JE, Heistad DD. Effects of local reduction in pressure on distensibility and composition of cerebral arterioles. Circ Res. 1991;68:338–351. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.2.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson KM, Lynch CM, Faraci FM, Lentz SR. Effect of mechanical ventilation on carotid artery thrombosis induced by photochemical injury in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:2669–2674. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2003.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang X, Yang F, Tan H, Liao D, Bryan RM, Jr, Randhawa JK, Rumbaut RE, Durante W, Schafer AI, Yang X, Wang H. Hyperhomocystinemia impairs endothelial function and eNOS activity via PKC activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2515–2521. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000189559.87328.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lubos E, Loscalzo J, Handy DE. Homocysteine and glutathione peroxidase-1. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:1923–1930. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antoniades C, Tousoulis D, Marinou K, Vasiliadou C, Tentolouris C, Bouras G, Pitsavos C, Stefanadis C. Asymmetrical dimethylarginine regulates endothelial function in methionine-induced but not in chronic homocystinemia in humans: effect of oxidative stress and proinflammatory cytokines. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:781–788. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.4.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korandji C, Zeller M, Guilland JC, Vergely C, Sicard P, Duvillard L, Gambert P, Moreau D, Cottin Y, Rochette L. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) and hyperhomocysteinemia in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Clin Biochem. 2007;40:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cardounel AJ, Cui H, Samouilov A, Johnson W, Kearns P, Tsai AL, Berka V, Zweier JL. Evidence for the Pathophysiological Role of Endogenous Methylarginines in Regulation of Endothelial NO Production and Vascular Function. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:879–887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603606200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tokuo H, Yunoue S, Feng L, Kimoto M, Tsuji H, Ono T, Saya H, Araki N. Phosphorylation of neurofibromin by cAMP-dependent protein kinase is regulated via a cellular association of N(G),N(G)-dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. FEBS Lett. 2001;494:48–53. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02309-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dayal S, Lentz SR. Murine Models of Hyperhomocysteinemia and Their Vascular Phenotypes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1596–1605. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.166421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lentz SR, Sobey CG, Piegors DJ, Bhopatkar MY, Faraci FM, Malinow MR, Heistad DD. Vascular dysfunction in monkeys with diet-induced hyperhomocyst(e)inemia. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:24–29. doi: 10.1172/JCI118771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dayal S, Baumbach GL, Arning E, Bottiglieri T, Faraci FM, Lentz SR. Deficiency of superoxide dismutase-1 sensitizes to endothelial dysfunction and hypertrophy of cerebral arterioles in hyperhomocysteinemic mice. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45:A22. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Folkow B, Hallback M, Lundgren Y, Weiss L. Background of increased flow resistance and vascular reactivity in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Acta Physiol Scand. 1970;80:93–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1970.tb04773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu J, Ismat FA, Wang T, Yang J, Epstein JA. NF1 regulates a Ras-dependent vascular smooth muscle proliferative injury response. Circulation. 2007;116:2148–2156. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.707752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cardounel AJ, Cui H, Samouilov A, Johnson W, Kearns P, Tsai AL, Berka V, Zweier JL. Evidence for the Pathophysiological Role of Endogenous Methylarginines in Regulation of Endothelial NO Production and Vascular Function. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:879–887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603606200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suda O, Tsutsui M, Morishita T, Tasaki H, Ueno S, Nakata S, Tsujimoto T, Toyohira Y, Hayashida Y, Sasaguri Y, Ueta Y, Nakashima Y, Yanagihara N. Asymmetric dimethylarginine produces vascular lesions in endothelial nitric oxide synthase-deficient mice: involvement of renin-angiotensin system and oxidative stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1682–1688. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000136656.26019.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kassab S, Garadah T, bu-Hijleh M, Golbahar J, Senok S, Wazir J, Gumaa K. The angiotensin type 1 receptor antagonist valsartan attenuates pathological ventricular hypertrophy induced by hyperhomocysteinemia in rats. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone. Syst. 2006;7:206–211. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2006.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sen U, Herrmann M, Herrmann W, Tyagi SC. Synergism between AT1 receptor and hyperhomocysteinemia during vascular remodeling. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45:1771–1776. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2007.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dayal S, Wilson KM, Leo L, Arning E, Bottiglieri T, Lentz SR. Enhanced susceptibility to arterial thrombosis in a murine model of hyperhomocysteinemia. Blood. 2006;108:2237–2243. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.