Abstract

The elopement of a child with Asperger syndrome was assessed using functional analyses and was treated in two school settings (classroom and resource room). Functional analyses indicated that elopement was maintained by access to attention in the resource room and obtaining a preferred activity in the classroom. Attention- and tangible-based interventions were compared in an alternating treatments design in both settings. Results validated the findings of the functional analyses. Implications for the assessment and treatment of elopement are discussed.

Keywords: Asperger syndrome, elopement, functional analysis, intervention

Elopement (attempts to leave an assigned area without consent) is prevalent among individuals with developmental disabilities (Jacobson, 1982). Intervention is warranted because elopement can endanger an individual's safety and disrupt the classroom. Functional analyses of elopement have shown that elopement may be maintained by different operant contingencies and can be reduced using function-based interventions (e.g., Kodak, Grow, & Northup, 2004; Lang, Rispoli, et al., 2009; Piazza et al., 1997; Tarbox, Wallace, & Williams, 2003). Because the results of previous research have suggested that the assessment setting may influence the results of functional analyses in some instances (Harding, Wacker, Berg, Barretto, & Ringdahl, 2005; Lang et al., 2008, 2009), the current study evaluated the influence of assessment setting on the analysis and treatment of elopement. Towards this aim, separate functional analyses and corresponding interventions were compared in two relevant settings.

METHOD

Participant and measurement

Joe, a 4-year-old boy who had been diagnosed with Asperger syndrome, participated. Elopement was defined as getting out of seat, turning away from the therapist, and running towards the door of the room. Data on elopement were collected using a 10-s partial-interval procedure. Data were converted to a percentage after dividing the number of intervals in which the target behavior occurred by the number of intervals in the session. Interobserver agreement data were collected on elopement during both the functional analyses and the intervention analyses on an interval-by-interval basis. Interobserver agreement was calculated by dividing the total number of intervals in which both data collectors scored either the presence or absence of elopement within a specific interval by the total number of intervals and converting this ratio to a percentage. Agreement measures were collected during 20% of all assessment and treatment sessions and were all 100%.

Settings

Separate functional analyses were conducted in Joe's typical classroom and a resource room at his school in which he received individual instruction. The classroom (approximately 5 m by 9 m) contained tables, chairs, and other typical classroom items. In addition to the implementer and data collectors, two or three teachers and between three and six other children with developmental delays were also present in the classroom during the functional analyses. The daily routine in this classroom consisted of a period in which students divided up into small groups or paired off individually with a teacher. The therapist conducted functional analyses at a table located near the center of the room and in sight of the door.

Teachers used the resource room, which contained cubicles (2 m by 2.5 m) for discrete-trial teaching. The cubicle used for the assessment had no windows and contained a table, two chairs, and only the materials needed for the particular assessment condition being implemented. During sessions in the resource room, Joe, the therapist, and one or two data collectors were present. Joe and the therapist were seated in chairs at the table (the typical instructional arrangement).

Functional analyses

Elopement was assessed during 5-min individual sessions across play (control), attention, escape, and tangible conditions. School policy prevented the implementation of an alone condition. The therapist did not restrain or block Joe during all conditions, and he had equal opportunities to engage in elopement across conditions. During the attention condition, the therapist sat next to Joe in her chair at the table, assumed the appearance of reading a notebook, and instructed him to play. Joe had free access to toys. If he eloped, the therapist retrieved him and provided verbal and physical attention, which continued for 5 s after the therapist had guided Joe back to the table. During the escape condition, the therapist delivered task demands based on Joe's individualized education plan. If he did not respond to the demand within 5 s, the therapist provided a gestural or model prompt indicating the correct response. If he still did not respond, the therapist used a physical prompt. Following elopement, the therapist retrieved him using a minimal amount of physical contact (i.e., guiding lightly by the arm) and refrained from providing verbal attention. The therapist delayed presentation of the next demand for an additional 5 s once she returned Joe to the table. In the tangible condition, a television and DVD player, which the class used frequently, were present. The therapist played Joe's preferred DVD for 10 s prior to the session, turned off the TV via a remote control to start the session, and turned on the TV with the remote following elopement. After the TV was turned on, Joe would either return to the area or the therapist would retrieve him in the same manner as described for the escape condition. During the play condition, Joe had unrestricted access to toys. The therapist did not present task demands, maintained close proximity to Joe, provided verbal praise and physical contact about every 10 s, and ignored elopement.

Within each of the functional analysis conditions, it was necessary to guide Joe gently to his seat following elopement, which may have been a form of attention. We addressed the potential confounding effects of this attention in several ways. First, during conditions in which attention was not a programmed consequence, the therapist did not to speak to Joe or make eye contact following elopement and only used minimal physical contact to guide him back to his seat. Second, the therapist delivered multiple forms of attention following elopement in the attention condition (i.e., the therapist gently picked Joe up to hold him, made eye contact, and told him, “You're a good boy, but I do need you to stay close to me”). Finally, the therapist did not provide physical contact during the tangible condition if Joe returned to the table on his own.

Functional analysis conditions were alternated according to a multielement design in each setting. The influence of the setting was examined systematically using an ABAB design, in which A represented the resource room and B represented the classroom. The same therapist, protocol, materials, task demands, condition sequence, and number of sessions were repeated across each phase of the reversal design.

Intervention analysis

Baseline data on elopement were collected in each setting during 30-min sessions in which the teacher responded to Joe's elopement in her typical manner. During baseline sessions in both settings, the teacher frequently provided attention in the form of a reprimand or redirection to an alternative activity. The teacher implemented two different intervention sessions in both settings. Both interventions involved noncontingent reinforcement (NCR) using the reinforcers identified in the functional analyses because NCR has been shown to be effective for reducing problem behavior (Hagopian, Crockett, van Stone, DeLeon, & Bowman, 2000; Hagopian, Fisher, & Legacy, 1994; Kodak et al., 2004; Piazza et al., 1997; Tarbox et al., 2003; see Tucker, Sigafoos, & Bushell, 1998, for a review).

The attention-based intervention consisted of the teacher maintaining close proximity to Joe and remaining oriented towards him for the entire session. For example, the teacher sat next to Joe when possible, and when working with another student, the teacher would move the other student closer to Joe so as to remain in close proximity. In addition, the teacher provided physical contact (e.g., pat on the back or high five), combined with affirmative statements (e.g., “Joe, you are a great student!”) every 30 s. The teacher closed the door to the room to prevent elopement and ignored elopement when it occurred. Tangible extinction was in place because the teacher did not deliver any tangible items during this condition.

The tangible-based intervention consisted of continuous and noncontingent access to the DVD, which was in Joe's view in the classroom. The teacher worked with other children or delivered instruction approximately 2 m away from Joe and did not interact with him in any way (i.e., the teacher did not deliver attention or tangible items following elopement). Therefore, the teacher implemented both tangible and attention extinction. Joe watched a small screen that the other students could not see with the volume reduced to minimize distractions in the classroom.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

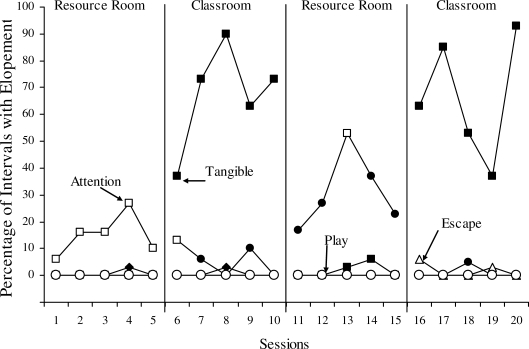

Figure 1 shows the results of the functional analysis. Levels of elopement were consistently elevated in the attention condition in sessions conducted in the resource room. Levels of elopement were consistently elevated in the tangible condition in sessions conducted in the classroom. These results showed that elopement was sensitive to different reinforcers across settings. This study extends elopement assessment research by empirically demonstrating the influence of setting on analyses of the variables that influence the occurrence of elopement.

Figure 1.

Results of functional analyses across the classroom and resource room settings.

Figure 2 shows the results of the treatment analyses. In the resource room, where elopement was sensitive to attention as reinforcement, the attention-based intervention resulted in relatively lower levels of elopement than did the tangible-based intervention. By contrast, in the classroom, where elopement was sensitive to access to the DVD movie as a reinforcer, the tangible-based intervention resulted in relatively lower levels of elopement. By showing the relative superiority of treatments more explicitly matched to setting-specific behavioral functions, our results support the validity of the distinct functional analysis results.

Figure 2.

Results of the attention-based and the tangible-based interventions conducted in the resource room (top) and in the classroom (bottom).

These results replicate the more general findings of previous research that suggests that setting can influence functional analysis results and that such an influence is pertinent to intervention design (e.g., Harding et al., 2005; Lang, O'Reilly, et al., 2009). It is important to note that the maintaining consequence for elopement may not always vary with setting. For example, Piazza et al. (1997) assessed elopement in one setting (i.e., adjacent classrooms) and used those results to design interventions that were effective in multiple settings (i.e., school, home, cafeteria, and hospital lobby) for 3 children.

Because elopement involves leaving a particular environment, its assessment requires some modification to typical functional analysis methods. One consideration necessary for repeated observation of the target behavior is the retrieval of the participant following elopement. Because retrieval is a form of attention and could confound results, previous research has attempted to offset this by providing attention noncontingently on a fixed-time schedule across all conditions (Kodak et al., 2004; Piazza et al., 1997; Tarbox et al., 2003). The current study included an alternative tactic that involved providing several forms of attention in tandem when attention was a programmed consequence (e.g., verbal and physical attention and eye contact) and providing minimal attention in only one form (e.g., retrieval) when attention was not a programmed consequence.

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution due to several limitations. First, the involvement of only 1 participant limits the generality of these results (i.e., the extent to which elopement will serve different functions across settings is unknown). Second, the interventions described here have several features that may make them inappropriate in some settings (e.g., providing continuous attention for 30 min and use of a television in a classroom). Third, elopement persisted, albeit at low levels, in the classroom following our brief intervention. Finally, the intervention involved closing the classroom door, which was not a component of baseline. Future research should investigate ways to make these and other function-based treatments more effective, socially valid, and practical for extended use in classrooms.

Acknowledgments

We thank the children, staff, teachers, and parents of the Capitol School of Austin. We also thank the Eli and Edythe L. Broad Asperger Research Center at the Koegel Autism Center, University of California, Santa Barbara for their support.

Contributor Information

Russell Lang, THE ELI AND EDYTHE L. BROAD ASPERGER RESEARCH CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA BARBARA.

Tonya Davis, BAYLOR UNIVERSITY.

Mark O'Reilly, UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN.

Wendy Machalicek, UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN–MADISON.

Mandy Rispoli, TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY.

Jeff Sigafoos, UNIVERSITY OF WELLINGTON, NEW ZEALAND.

Giulio Lancioni, UNIVERSITY OF BARI, ITALY.

April Regester, THE ELI AND EDYTHE L. BROAD ASPERGER RESEARCH CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA BARBARA.

REFERENCES

- Hagopian L.P, Crockett J.L, van Stone M, DeLeon I.G, Bowman L.G. Effects of noncontingent reinforcement on problem behavior and stimulus engagement: The role of satiation, extinction, and alternative reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2000;33:433–449. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian L.P, Fisher W.W, Legacy S.M. Schedule effects of noncontingent reinforcement on attention-maintained destructive behavior in identical quadruplets. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:317–325. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding J, Wacker D.P, Berg W.K, Barretto A, Ringdahl J. Evaluation of relations between specific antecedent stimuli and self-injury during functional analysis conditions. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 2005;110:205–215. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2005)110<205:EORBSA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson J.W. Problem behavior and psychiatric impairment within a developmentally disabled population: I. Behavior frequency. Applied Research in Mental Retardation. 1982;3:121–139. doi: 10.1016/0270-3092(82)90002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodak T, Grow L, Northup J. Functional analysis and treatment of elopement for a child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:229–232. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang R, O'Reilly M, Lancioni G, Rispoli M, Machalicek W, Chan J.M, et al. Discrepancy in functional analysis results across two applied settings: Implications for intervention design. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42:393–398. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang R, O'Reilly M, Machalicek W, Lancioni G, Rispoli M, Chan J.M. A preliminary comparison of functional analysis results when conducted in contrived versus natural settings. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2008;41:441–445. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang R, Rispoli M.J, Machalicek W, White P.J, Kang S, Pierce N, et al. Treatment of elopement in individuals with developmental disabilities: A systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2009;30:670–681. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza C.C, Hanley G.P, Bowman L.G, Ruyter J.M, Lindauer S.E, Saiontz D.M. Functional analysis and treatment of elopement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30:653–672. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarbox R.S, Wallace M.D, Williams L. Assessment and treatment of elopement: A replication and extension. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:239–244. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker M, Sigafoos J, Bushell H. Use of noncontingent reinforcement in the treatment of challenging behavior: A review and clinical guide. Behavior Modification. 1998;22:529–547. doi: 10.1177/01454455980224005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]