Abstract

This research uses multiple-sample longitudinal data from different test batteries to examine propositions about changes in constructs over the lifespan. The data come from three classic studies on intellectual abilities where, in combination, N=441 persons are repeatedly measures as many as 16 times over 70 years. Cognitive constructs of Vocabulary and Memory were measured using eight different age-appropriate intelligence test batteries, and we explore possible linkage of these scales using Item Response Theory (IRT). We simultaneously estimate the parameters of both IRT and Latent Curve Models (LCM) based on a joint model likelihood approach (i.e., NLMIXED and WINBUGS). Group differences are included in the model to examine potential inter-individual differences in levels and change. The resulting Longitudinal IRT (LIRT) analyses leads to a few new methodological suggestions for dealing with repeated constructs based on changing measurements in developmental studies.

Classical research on cognitive abilities has provided information about the growth and decline of intellectual abilities over the lifespan (i.e. Cattell, 1941, 1998; Horn, 1988, 1998). Many recent analyses of this topic use some form of longitudinal mixed-effects, multi-level, latent curve models (Meredith & Tisak, 1990; McArdle, 1986, 1988; McArdle et al, 2002; McArdle & Nesselroade 2003). One of the basic measurement assumptions of all latent curve models is longitudinal measurement equivalence – i.e., the same unidimensional attribute is measured on the same persons using exactly the same scale of measurement at every occasion. Tests of these assumptions starts by measuring the same variables at each occasion and considering tests of factorial invariance (e.g., McArdle, 2007). However, the classical requirements of exactly equivalent scales of measurement is often impractical and not often achieved. These measurement issues have been raised in classic treatments of the analysis of change (e.g., Harris, 1961; Cattell, 1966; Wohwill, 1973), but have not fully been resolved (e.g., Burr & Nesselroade, 1991; Collins & Sayer, 2001).

One creative solution to this problem of changing scales was illustrated in the work of Bayley (1956) in her analysis of data from the seminal Berkeley Growth Study. Individual growth curves of mental abilities from birth to age 26 were plotted for a selected set of males (Fig. 1a) and females (Fig. 1b). In the early stages of this data collection (circa 1929), Bayley (among many others) assumed any measurement occasion within each study should incorporate an “age-appropriate” intelligence test – i.e., a version of the Stanford-Binet (S-B) at ages 6 -17, then the Wechsler-Bellevue Intelligence Scale (W-B) at ages 16–26. While these tests measure specific intellectual abilities, they are not administered or scored in the same way and may measure different intellectual abilities at the same or different ages. However, Bayley was interested in using the statistical techniques applied to physical growth curves, so she created the individual growth curves represented in Figure 1 by adjusting the means and standard deviations of different mental ability tests at different ages into a common metric (based on z-scores formed at age 16). As Bayley suggested, “They are not in ‘absolute’ units, but they do give a general picture of growth relative to the status of this group at 16 years. These curves, too, are less regular than the height curves, but perhaps no less regular than the weight curves. One gets the impression both of differences in rates of maturing and of differences in inherent capacity.” (p. 66). She also noticed the striking gender differences in dispersion of the resulting curves.

Figure 1.

Growth curves of intellectual abilities from the Berkeley Growth Studies of Bayley (1956; Age 16 D scores).

This classic study can be considered an early application of what is now termed linked or mapped measurement scaling of growth data. The practical scaling method used by Bayley permitted the analysis of fundamental features regarding growth curves of cognition, and appeared to put mental growth on the same scientific footing as physical growth. Nonetheless, not all researchers were convinced by the merits of this approach. In one important critique Wohlwill (1973, p.75) suggested, “Yet the pooling of data as conceptually diverse as Wechsler-Bellevue raw scores and Stanford-Binet mental age scores is surely suspect. For the reasons previously indicated growth functions based on the latter are altogether artifactual, so that pooling intelligence test scores from this scale together with other intelligence test scores can hardly be expected to yield useful information concerning the growth function” (p.75-76).

These kinds of critiques highlight important technical concerns about the possible and most appropriate ways to examine these issues. In this paper we use concepts from Item Response Theory (IRT) to create measurement linkages for tests even though the same measurement device was not used on all occasions. We merge IRT with concepts from Latent Curve Modeling (LCM) for examining growth and change over age using data pooled from mmultiple longitudinal samples.

Longitudinal Growth and Change Modeling

A great deal of prior work on structural equation modeling (SEM) has been devoted to the problems of longitudinal analysis. This includes important work on the auto-regressive simplex models, as well as new ways to deal with common factors and measurement error in panel data (i.e. Wiley & Wiley, 1970; Sörbom, 1975; Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1979; Horn & McArdle, 1980). Meredith & Tisak (1990) proved how the “Tuckerized curve” models (after Tucker, 1958; cf., Rao, 1958) could be represented and fitted using SEM based on restricted common factors. These SEM representations of growth curve models offered the possibility of representing a wide range of alternative models and quickly led to other methodological and substantive studies (McArdle, 1986, 1988, 1989) The LCM approach to modeling change has since been expanded upon and used by many researchers (e.g., Willett & Sayer, 1994; Duncan & Duncan, 1995; Tisak & Tiask, 1996; Muthen & Curran, 1997; Metha & West, 2000; Fan, 2003). LCMs can now be estimated from observed raw score longitudinal data which are both unbalanced and incomplete using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE, as in Little & Rubin, 1987; McArdle & Anderson, 1990; McArdle & Hamagami, 1992, 2001; Hedeker & Gibbons, 1997; McArdle & Bell, 2000). These formal developments in LCM overlap with many recent developments of multi-level models (Goldstein, 1995; Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992; Snijders & Bosker, 1994; Woodhouse, Yang, Goldstein, & Rasbash. 1996) or mixed-effects models (Singer, 1998; Verbeke et al, 2000). The important work by Browne & du Toit (1991) showed how the nonlinear dynamic models can also be considered in this same framework (see Cudeck & du Toit, 2003; McArdle & Hamagami, 1996, 2001; Pinherio & Bates, 2000).

These LCM developments also led to a revival of practical experimental variations based on planned incomplete data. For example, in both McArdle and Woodcock (1997) and McArdle, Ferrer-Caja, Hamagami & Woodcock (2002), the cognitive test-retest data were collected by a design with varying intervals of time – a “time-lag design.” This timelag design used here created sub-groups of persons based on the time delay between testings, and a “planned incomplete data” approach was used to estimate parameters in a pooled analyses. Similar incomplete data latent growth models have also been used when the separate group data was neither planned nor randomly selected. In these cases, the available incomplete data pooling techniques can stll be applied to describe a limited mixture of age-based and time-based models using only two-time points of data collection; i.e., an “accelerated longitudinal design” (Bell, 1953, 1954; McArdle & Anderson, 1990; McArdle & Woodcock, 1997; McArdle & Bell, 2000), and a multipe group pooling approach proved especially useful in dealing with “cohort-sequential” data collections in studies across the life-span (i.e. McArdle & Hamagami, 1992; Duncan & Duncan, 1995; cf, Swanson, 1999).

A seemingly separate literature has focused on the estimation of latent traits using item response theory (IRT) models (Fischer & Molenaar, 1995; van der Linden & Hambleton, 1997; Embretson & Reise, 2000; Bond & Fox, 2001; Rost, 2002; De Boeck & Wilson, 2004). IRT can be considered a collection of models designed to yield estimates of one or more latent traits based on responses to a set of individual items, whether binary (dichotomous) or multi-category (polytomous). The basic model of Rasch (1960, 1966) for dichotomous items was expanded by Fisher (1987, 1999) for use in the measurement of change over time (also see Fisher & Parzer, 1991; Fisher & Siegler, 2004). In one SEM-IRT type integration, Hamagami (1998) showed how the longitudinal invariance of the factorial structure of a set of items could be evaluated using available SEM software (e.g., LISCOMP). This approach has been extended using general SEMs which show all IRT are latent variable SEM with discrete indicators, so standard distinctions are artificial (e.g., McDonald, 1999; Muthen, 2002; Skrondal & Rabe-Hesketh, 2004). Other aspects of longitudinal-item response models are found in the work of Wilson (1989), Embretson (1991), Mislevy and Wilson (1996), Ferrando (2002), and some key numerical issues have been raised by Fischer (2005), Feddag and Mesbah (2005), Rijmen, De Boeck and van der Maas, (2005), and Pastor & Beretvas (2006).

Changing Scales in Longitudinal Data

One of the most basic measurement requirements in all latent curve analyses is longitudinal measurement equivalence -- where the same attribute is measured on the same person in the same scale at every occasion. For practical reasons, many longitudinal researchers make sure to use exactly the same tests (or items) at every repeated occasion. However, even when such precautions are taken, the meaning and function of the test(s) can change (Cattell, 1966; Horn & McArdle, 1992; McArdle & Cattell, 1994). When the same measures are repeated on the same persons, the assumption of metric factorial invariance over time can be examined using longitudinal SEMs (e.g., McArdle, 1988; 2007; McArdle & Nesselroade, 1994, 2003; Hancock, Kuo & Lawrence, 2001; Sayer & Cumsille, 2001; Leite, 2007).

But another common scenario in longitudinal studies is when the primary measurements are not “exactly the same” from one occasion to the next. Scales are altered for many good reasons, including age-appropriateness, bad experiences in prior usage of some tests, new and improved test batteries, and so on (see Jones et al, 1971; Wohwill, 1973). These considerations are sensible and practical, so it is likely that changing measurements of the same constructs will remain a feature of developmental research for many years to come. Unfortunately, researchers using growth curve methods can not be sure how to separate differences in the scales over time from changes in the constructs over time. Most specifically, if there are differences in test forms and test batteries, the difficulty of this problem increases. This problem is relevant in life-span developmental studies because we often include a wide range of ages or attempt to combine different studies based on different groups of persons measured on similar constructs.

Longitudinal researchers have approached these problems in several different ways:

1. Over-Time Prediction

A popular solution to this problem is to simply choose a mathematical-statistical model that does not require identical measurements. This choice is often made indirectly, such as when the analyst simply describes the correlations in scores over time and the “constancy” of individual differences (as in Jones et al, 1971). In a multiple regression prediction over time, earlier scores are used to predict later scores, and regression type models based on latent variables are popular (i.e. Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1979). Such an approach seems necessary in long-term longitudinal research where the key constructs are considered to be different from one time to the next (i.e., in childhood versus adulthood). However, these prediction models do not attempt to directly estimate change over time at the individual level (Nesselroade & Baltes, 1979; McArdle & Nesselroade, 2003).

2. Within Occasion Re-Scoring

Another simple alternative is based on transforming the raw scores into z-scores within a time point (as in Bayley, 1956; Fig. 1). Under the assumption that the same construct is measured by two different scales, one variable is simply transformed into another scale by a regression calculation, usually using a focal occasion (e.g., 16 years old). This approach can lead to several potential problems. First, it removes the means and standard deviations within each time or age, so any systematic growth or change related to the these statistics cannot be easily identified. Second, the accuracy is limited by the size of the correlation among the observed scores, and the estimated scores will be attenuated unless a residual term is also imputed. Third, longitudinal data collections often have many different cross-battery rescalings to consider (e.g., for variables W, X, Y, and Z), so many regressions could be imputed using multiple pairs, or as triplets, or as an aggregate of several different occasions of overlap. Finally, the measured sample at any time may be shifting due to attrition, yet each regression can only be conducted with a selected part of the available sample.

3. Absolute Scaling

A related longitudinal scaling method was proposed by Thurstone (1928) for cognitive scores. In this work he first assumed cognition over age could be represented as a linear growth model with linearly increasing means and linearly increasing standard deviations. Next, he assumed any measurement of this construct at any age should be rescaled to fit this linear growth pattern. Using these assumptions, the group means and deviations of different tests at different ages should follow a linear pattern back to the starting point – i.e, the variance went to “absolute zero.” This creative approach used the latent curve parameters to create weights for a common metric. These linear assumptions seem unreasonable, so there seem to be very few applications of this scaling method (e.g., McArdle, 1988).

4. SEM with Convergent Factor Patterns

It is possible to consider a simultaneous structural model for the multiple scales where some measures are missing at some occasions. The general problem of scale overlap can be seen in common factor model of multivariate repeated measures where the longitudinal data is accounted for by constant loadings but changing factor scores – a “curve of factor scores” model (McArdle, 1988, 1989; Leite, 2007). To the degree multiple measurements are made at multiple occasions, this common factor hypothesis about the change pattern can be estimated, and even rejected (i.e. McArdle & Woodcock, 1997; McArdle et al, 2002). It has been shown that the critical assumption of invariant loadings over time at the first-order allows us to model the changes in the common factor scores in terms of a latent growth model at the second-order (as in McArdle, 1988, 1989; McArdle & Woodcock, 1997; Hancock, Kuo & Lawrence, 2001; Sayer & Cumsille, 2001; Leite, 2007). A first problem is that the scaling of the factor scores requires some fixed factor means, and this is typically done by assigning a zero factor mean at the first occasion (e.g., see Cattell, 1972; McArdle, 1988, 1989). With changing measures, we assume the same factor score can be measured by different variables at the different times, and the common factor equation is expressed for the possible patterns of measurement for the multiple measures. Although this is a compelling idea, it is important to consider how much observed information is needed to identify and estimate these model parameters, especially when using standard SEM computations based on high-dimensional integration. In general, the identification status and the ease of estimation of the covariance parameters depends on the number of observed measurements and occasions and secondly depends on the overlap or “coverage” of multiple batteries within each time. If we have a large number of changing measurements we can end up with low covariance coverage, and a common factor measurement model with or without invariance may not be identified (see McArdle, 1994; McArdle & Woodcock, 1997; McArdle & Hamagami, 2004).

5. IRT Linkage of Common Items

As a contemporary combination of the approaches listed above, we can try to estimate common scales of measurement using an IRT approach for the items in changing scales. In one specific form of this model we can postulate Rasch-based restrictions -- a single common factor for a large set of items, including equal loadings on the items. These simplifying assumptions allow planned missing items within occasion due to the experimental design (i.e., not due to the person’s refusal; as in McArdle, 1994). This form of incomplete data IRT approach can be used to estimate a measurement model of the common traits over time, but unless some form of item overlap is present it will not be possible to test the validity of the measurement invariance constraints. In any case, further longitudinal modeling of the factor score estimates can tbe based on mixed-model latent growth curve analyses. Given enough information, the parameters of growth-measurement models can be estimated simultaneously (as in Fischer, 1989; Feddag & Mesbah, 2005; Rijmen et al, 2005; Pastor & Beretvas, 2006). The strengths and weakness of each approach, as well the computational techniques available to carry out the estimation, have only recently been explored, but the general idea of fitting a longitudinal growth model together with an IRT model fits naturally into the contemporary multi-level IRT research (e.g., Kamata, 2001; Goldstein & Browne, 2002; Fox & Glas, 2002; De Boeck & Wilson, 2004).

Summary of the Current Approach

In the next section we present details on real life-span longitudinal data where, on at least one oaccasion, one or two from a total of eight different standardized tests have been administered. We describe eight cognitive scales where the choice of the specific measurement for each occasion is slightly different, but based on using the most “well regarded” and the “age-appropriate” test(s) available at the time. To limit these analyses, we focus on two key constructs in cognitive aging research -- Vocabulary and Memory. Next, we define the features of multi-level latent curve models which allow us to describe the life-span features of the growth and changes of these abilities. Here we also emphasize our assumptions about incomplete data. We propose a longitudinal growth model based on a Longitudinal Invariant Rasch Tests (LIRT), define the simplifying model assumptions, and show how this approach can be used to bring different measures of the same construct into a common scale. We consider several techniques for linkage across measurement scales and across multiple groups and we fit a unidimensional Rasch model to item responses and a latent curve model together with changing latent scores over age and groups.

These LIRT models can be estimated using either multiple stages or simultaneous methods, and we highlight the simultaneous estimation methods in this paper (c.f., McArdle & Nesselroade, 2003). In general, we emphasize how these kinds of LIRT analyses can provide a new and practically useful solution to the classic problem of changing measurement scales with different groups. We do not view LIRT as a methodological breakthrough, but instead see the LIRT approach as a practical integration of important theoretical questions and contemporary modeling principles. We also show how LIRT leads to key issues for future longitudinal data collections and analyses.

METHODS

Participants

The data come from three long-term longitudinal studies of the growth (and decline) of a variety of cognitive abilities (see Table 1). The combination of these studies leads to N=419 persons measured from T=1 to 16 occasions on ages ranging from A=2 ½ to 72 years (as in McArdle et al, 2001). An overview of the cognitive testing in these three different studies follows:

The Berkeley Growth Study (BGS; n = 75) was initiated by Nancy Bayley in 1928 to trace the normal intellectual, motor, and physical development through the first year (see Jones et al, 1971). The original participants of the BGS were selected for study as infants born in local hospitals in Berkeley, CA. Data collection continued through childhood and adolescence with the sample taking an intelligence test every year until age eighteen. The sample was measured repeatedly on these kinds of cognitive tests at ages 21, 26, 36, 50, and 70. The two most recent measurement occasions included the spouses of the subjects bringing the total sample size to 124. The sample is approximately half male (63) and half female (62).

The Guidance-Control Study (GCS; n = 206) also began in 1928 by Jean Macfarlane (also in Jones, et al 1970). The participants were selected from the population of every third infant born in Berkeley between January 1928 and June 1929. Half of the GCS participants’ mothers were offered guidance by the principal investigator about general issues of childhood behavior and development (see Jones & Meredith, 2000). The participants whose mother’s received guidance were called the Guidance Group; the other participants were called the Control Group. The participants from this study were repeatedly measured on various forms of intelligence tests almost every year from age 6 to age 15 and then at age 18, 40, and 53. The final two measurement occasions also included measurements of their spouses.

The Bradway-McArdle Longitudinal Study (BML; n =111) began in 1930 when the participants were tested in the Bay Area of California as part of the standardization sample of the Revised Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale (see Bradway & Thompson, 1962). At the initiation of the study the participants were between the ages of two and five and a half. Katherine Bradway retested the participants in 1941 for her doctoral thesis and continued the longitudinal study by testing the participants in 1957 and 1969. McArdle and colleagues followed-up these participants in the 1980s and the 1990s (see McArdle et al, 2001). The Bradway-McArdle and both Berkeley samples are predominately Caucasian, from approximately the same cohort (~1928), from the San Francisco area, and have above average social economic status.

Table 1.

Summary of available data from multiple testing occasions for three longitudinal studies

| Age | Berkeley Growth BGS (n=61) |

Guidance-Control GCS (n=206) |

Bradway-McArdle BML (n=111) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 – 5 ½ | SB-L, SB-M (111) | ||

| 6 | 1916 SB (60) | 1916 SB (205) | |

| 7 | 1916 SB (47), SB-L (8) | 1916 SB (204) | |

| 8 | SB-L (51) | SB-L (187) | |

| 9 | SB-L (53) | SB-L (94), SB-M (98) | |

| 10 | SB-M (53) | SB-L (102), SB-M (88) | |

| 11 | SB-L (48) | SB-L (77) | |

| 12 | SB-M (50) | SB-L (90), SB-M (43) | |

| 13-14 | SB-L (42) | SB-L (82), SB-M (97) | SB-L (111) |

| 15 | SB-M (51) | ||

| 16 | WB-I (48) | ||

| 17 | SB-M (44) | ||

| 18 | WB-I (41) | WB-I (157) | |

| 21 | WB-I (37) | ||

| 25 | WB-I (25) | ||

| 29 | WAIS, SB-L (110) | ||

| 36 | WAIS (54) | ||

| 40 | WAIS (156) | WAIS, SB-LM (48) | |

| 53 | WAIS-R (41) | WAIS-R (118) | WAIS (53) |

| 63 | WAIS, WJ-R (48) | ||

| 67 | WAIS, WJ-R (33) | ||

| 72 | WAIS-R, WJ-R (31) |

Notes: (1) Available sample size for specific tests is contained in parentheses; (2) Test Abbreviations: SB = Stanford-Binet, WB = Wechsler-Bellevue Intelligence Scale, WAIS = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, WAIS-R = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised, WJ-R = Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery – Revised.

Available Vocabulary & Memory Measurements

The raw data for all samples were recoded at the item level from the archival records of all three longitudinal studies. This analysis focuses on the Vocabulary and Memory Span items and specific scoring details are presented in the Table 2. The Wechsler and Woodcock-Johnson scales have a specific set of items which are used to form the Vocabulary and Memory Span sub-scales. To add complexity to this problem, the scoring procedures for these items change from one version to the next. The use of the S-B scales are a more complex problem because the Vocabulary and Memory Span items are scored in a different way and are interspersed throughout the entire scale. In addition, the items representing the Vocabulary and Memory Span constructs are only presented if a person reaches a specific “age-level” on the overall test.

Table 2.

Descriptions of administration and scoring of alternative scales

| 2a: Scoring of Alternative Vocabulary tests | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vocabulary Test | Items | Scoring | Response Typea |

Stopping Rule | Item Overlap |

| 1916 Stanford-Binet | 50 | 0, ½, 1, coverted to 0, 1, 2 |

Define | 5 consecutive failures |

34 with SB-L, SB-LM |

| Stanford-Binet Form L & LMb | 45 | 0,1 | Define | 5 consecutive failures |

34 with 1916 SB |

| Wechsler-Bellevue – Form I | 42 | 0, 1, 2 | Define | 5 consecutive failures |

|

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale |

40 | 0, 1, 2c | Define | 5 consecutive failures |

33 with WAIS-R |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised |

35 | 0, 1, 2 | Define | 5 consecutive failures |

33 with WAIS |

| WJ-R Oral Vocabulary Synonyms |

20 | 0, 1 | Name Synonym |

4 consecutive failures |

1 with WAIS |

| WJ-R Oral Vocabulary Antonyms |

24 | 0, 1 | Name Antonym |

4 consecutive failures |

|

| WJ-R Picture Vocabulary | 58 | 0, 1 | Name Object |

6 consecutive failures |

|

| 2b: Scoring of Alternative Memory Span tests | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intelligence Test | Items types | Attempts | Stopping Rule |

| Stanford-Binet | Digits Forward | 3 | * |

| Digits Backward | 3 | * | |

| Memory for Words | 3 | * | |

| Memory for Sentences | 3 | * | |

| Wechsler Memory | Digits Forward | 2 | 2 incorrect on same length |

| Digits Backward | 2 | 2 incorrect on same length |

|

| Woodcock Johnson – Revised |

Memory for Words | 1 | 4 consecutive failures |

| Memory for Sentences | 1 | 4 consecutive failures |

|

Notes: (1) Define - participant is asked to define the word presented, Name Synonym – participant is asked to name a word that has the same meaning as the word presented, Name Antonym – participant is asked to name a word that has the opposite meaning as the word presented, Name Object – participant is asked to name the object which is presented visually. (2) Stanford-Binet Form M does not contain a vocabulary tests (3) Except for the first three items, which are scored 0, 2.

Notes: (1) All items were scored correct (=1)/ incorrect (=0), except for the WJ-R Memory for Sentences (0=wrong, 1=partial, 2=right); (2) The items in the Stanford-Binet are presented by difficulty, not by type of intelligence; (3) The participants were not administered every memory span item on the Stanford-Binet; (4) The items presented depended on each participants individually assigned starting and stopping points for each test.

It is useful to consider the multiple patterns of available test data. At each occasion of measurement, participants received only one or two of the eight cognitive test batteries. In all three studies combined, with 8 different scales, it is possible for many combinations of overlap or “coverage” among different scales. However, as seen in Table 1, there are only five instances where there was a direct administration of more than one scale at the same occasion (e.g., the S-B form L and the S-B form M were administered in the BML in 1931 at ages 2 ½ -5).

Substantially more coverage was available at the item level. In addition to overlap because two scales were administered at the same testing occasion, item overlap occurred because the same item was administered on multiple test forms. For Vocabulary, 34 common items exist on the 1916 S-B and the S-B form L, 45 items are common to the S-B forms L and LM, and 33 items are common to the WAIS with the WAIS-R. For Memory, Digit Span items of a common length appear in the 1916 S-B and the three revised editions of the S-B (forms L, M, LM), and the Digit Span items of the W-B are the same as the WAIS and WAIS-R. (This assumes that Digit Span items of the same length are the same item even though the specific numerals the participants were asked to remember were different.)

Another potentially important issue is that incomplete data are created within each test because of starting and stopping rules on each of the scales. Items were skipped when thought to be too easy (credit is given), and items the participant did not reach are assumed to be too hard (credit is not given). In all analyses presented here we treated items that were not administered as missing. This was a conservative strategy, so we examined several other ways to score the items, including giving credit to items before the starting point (assumed correct), not giving credit to items after the stopping rule (assumed incorrect), and other combinations. A preliminary analysis of these methods, at the item level, produced no notable differences in the results from any model (i.e., the estimates across both coding schemes r(a,b) >0.98), so we only present the conservative scoring strategy here.

This data collection raises another practical problem when there is a complete lack of item overlap. In these studies the Wechsler-Bellevue was never administered at the same time as any other tests, and the Vocabulary items on the W-B were never given on another test. If we simply ignored these occasions we would lose potentially valuable longitudinal data, so we explored several alternative solutions. We found it was most useful to include items from the Information scale, both because the Information-Vocabulary subscales are highly correlated (r(i,v)>.8), and because the W-B, WAIS, and WAIS-R share Information items (the Information subscale of the W-B shares 16 items with the WAIS and 9 items with the WAIS-R. The WAIS and the WAIS-R information subscales share an additional 11 items, totaling 20 shared items between the two tests). Using this set-up we found that common persons and common item linking can be used to equate the Wechsler-Bellevue to the WAIS and WAIS-R, which in turn are linked to the other Vocabulary tests. We examined the impact of this use of shared information in several ways, but we could not find any notable impact on the results. For this reason the only solutions presented here use this overlapping item collection.

Available Longitudinal Data

Given all these considerations, the net result is a large set of scores on cognitive test items. The Vocabulary scores are based on N=419 at an average of T=6 occasions with an average of I=34.9 specific items per testing occasion (i.e., D=2,507 individual records with 87,420 individual item scores). The Memory Span scores are based on N=416 participants at an average of T=7.5 occasions with an average of I=8.4 specific items per testing occasion (i.e., D=3,107 individual records and 25,943 individual items). However, even with all these longitudinal item data the coverage of all possible items at all possible occasions is only about 5%. That is, if all of these persons had been measured on all possible items (I=278 or I=76) at all possible occasions (T=16) the result would be almost twenty times more data than are currently available. It is clear that the historical choices to administer different tests at specific occasions have created a challenging problem for subsequent developmental analysis and inference.

MODELS

Latent Growth-Decline Curve Models

The overall goal of the current longitudinal analysis is to examine group and individual differences in the trajectory of people over the full life-span, so we start with a focus on growth models. In the latent curve model used here we assume we have observed the variable Y on persons (n=1 to N) at multiple occasions (t=1 to T), and we can write

| [1] |

where we separate the within-time measurement equation from the over-time functional change equation. In the simple form of a measurement equation within each time we separate the construct or trait score (g) from the time-specific unique scores (u). These unique scores are assumed to contribute variation to the observation at a given time but are independent of the trait score, and are independent of other unique scores across occasions of measurement. In this sense, they may be considered as unique factors with both specific (i.e., state) and random error components. For the purposes of all further analyses, these unique scores are distributed with a mean zero, a single unique variance (ψ2), and zero correlation with any of the other latent scores.

In the functional equation, the g0n are latent scores representing an individual’s initial level (i.e. intercept), g1n are scores representing the individual linear change over time (i.e. slopes). The set of A[t] are termed “basis” weights that define the timing or “shape” of the change over time for the group (e.g., age at testing), and we do not restrict the test occasion to be administered at a specific age. There is no additional residual in the functional equation, but this would be considered in multiple construct models (e.g., McArdle, 1988; McArdle & Woodcock, 1997). The latent components of this functional equation are assumed to have means, variances and covariances, and related to other variables. In a multi-level form we write these equations as

| [2] |

where the second-level scores are assumed to have means (μj) and covariances (ϕ02, ϕ12,ϕ01), and are accounted for by using a regression based on external variables (X) with regression intercepts (ν), coefficients (γ) and disturbance terms (d).

Changes Implied from the Basis of the Latent Curve

The measurement equation above defines the separation of the g[t] from u[t] in the same way as a classical model of a true-score separated from time dependent error (e.g., Gulliksen, 1950). But in the functional equation, the constant part of the true score is the intercept or level score (g0), while the change in the true score from one time to another (g[t]- g[t+k]) is a function of the slope score (g1) and the change in the time-based loadings (α[t]- α[t+k]). This interpretation is clarified when we write the first difference among successive latent scores as

| [3] |

to isolate the interpretation of changes over time. This interpretation as a difference equation obviously requires the scaling of the latent scores g[t] to be identical at each occasion, and it is clear that substantial problems can arise if this assumption is not met (e.g., Cattell, 1966).

To the degree these scaling assumptions are met, we benefit from several other features of the latent curve models. The A[t] basis coefficients determine the metric or scaling and interpretation of these changes, so alterations of A[t] can lead to different curves. If we require all A[t]=0, we effectively eliminate all slope parameters, whereas if we fix A[t]=t we represent a “straight line” or “linear” growth curve. Alternatively, we can allow the latent basis to be estimated and take an optimal shape for the group curve (i.e. Rao, 1958; Tucker, 1958; Meredith & Tisak, 1990; McArdle, 1986). Restrictive nonlinear forms of the latent basis coefficients can be used to reflect specific growth hypothesis (McArdle & Nesselroade, 2003). Popular nonlinear models include polynomial models (quadratic, cubic) and exponential forms (e.g., Coleman, 1968; McArdle & Hamagami, 1996; McArdle et al, 2002). It is also possible to fit and compare a set of models where the basis is written as Equation [1] with either

| [4] |

The basis parameters represent a series of specific hypothesis to be tested. The first three models allow either (1) no systematic change over time, (2) linear change with time, or (3) linear change with age at the time of testing. The distinctions among the first three models have been discussed some depth in previous literature (e.g., McArdle & Bell, 2000). The last two models have been used to represent (4) an exponential and non-decreasing change with age, or (5) a more complex dual increasing-decreasing change over age. In this last model the basis is formed as a difference between two exponentials shapes with rates of growth (πg) and decline (πd). Of course, this model is not novel in mathematics and statistics – it corresponds to a second order constant coefficient differential equation in continuous time, a second order auto-regression model in discrete time series, and a two-equation state space model (McArdle & Nesselroade, 2003). This final dual exponential basis is of interest here when interpreted in terms of “competing forces over age”, and has been found to provide a reasonable fit using other life-span abilities (i.e., McArdle et al, 2002). It is clear that the equivalence of measurement is required before we cany consider any nonlinear form of latent changes (e.g., Carroll, Ruppert & Stefanski, 1995).

Item Response Measurement Models

Another part of our approach follows the analysis of latent traits using item response theory (IRT) models (Fischer & Molenaar, 1995; van der Linden & Hambleton, 1997; Embretson & Reise, 2000; Bond & Fox, 2001; De Boeck & Wilson, 2004). IRT can be considered as a collection of models designed to yield estimates of one or more latent traits based on responses to a set of individual items, whether binary (dichotomous) or multi-category (polytomous). The basic model of Rasch (1960, 1966) for dichotomous items can be defined as

| [5] |

where Pri,n is the probability of the correct response (Pr=1) of person n to item i, the latent score gn, (usually termed θn) is the true-score or ability (trait level) of person n, and βi is the difficulty of item i. In this simple form, the log-odds of the correct response increases to the degree that the person’s ability is higher than the item difficulty. A corresponding model of the probability of a correct response can be written as a standard exponential ratio (i.e., exp(Pr)/{1+exp(Pr)}).

The item data we examine are collected at different occasions of measurement (t=1 to T), so we extend this model by writing

| [6] |

where, at time t, the Pr[t]i,n is the probability of the correct response (Pr=1) of person n to item i, the latent score g[t]n, is the true-score or ability (trait level) of person n at time t, and the difficulty of the item βi does not change with time. This assumption of measurement invariance over time at the item level (i.e., βi is constant over t=1 to T) is a testable hypotheses with complete longitudinal data at several occasions (McArdle & Nesselroade, 1994; McArdle, 2007). However, when the scales change from one time to the next, with only minimal overlap, the assumption of item invariance over time is not so easily tested. Nevetheless, given these assumptions and adequate fit to the overall measurement model, the Rasch estimated ability score g[t]n can be considered a valid interval scaled measure, and substituted into Eq. [1].

Many more complex variations of this basic model can be introduced. In the data presented here some items used in these analyses can have graded outcome scores for some variables (i.e., 0, 1 or 2), so we can use a partial credit model (Masters, 1982; Wilson & Draney, 1997). The partial credit model can be written for any item as

| [7] |

where, at time t, the PrX[t]i,n= Pr(X[t]i,n= x ∣ X[t]i,n = x or X[t]i,n = x-1) is the probability the response of person n to item i is in category x, given that the response is in either category x or x-1. This reduces to the longitudinal Rasch model of [6] when dichotomous items are used.

In another alternative, we can write the classic two-parameter logistic model (Birnbaum, 1968) as

| [8] |

where, at each time t, the discrimination parameter λi modifies the difference and hence the probability of the correct response (Pr[t]=1) of person n to item i at time t. While there are now two independent characteristics of each item, the intercept βI and slope λI, these are both assumed to be invariant over time. The generalized partial credit model (Muraki, 1992) combines the partial credit model and two-parameter logistic model by incorporating the slope parameter into the adjacent logits equation (see [7]), and this can be added to the longitudinal model (Eq. [8]). These models involving the slope parameter may be needed to achieve fit, and this raises a number of critical issues in measurement theory (see Bock, 1997; Andrich, 2002).

ESTIMATION AND PROGRAMMING

Modeling Incomplete Longitudinal Curves

The longitudinal life-span data considered here are incomplete for many different reasons: (a) The number of occasions was not the same across the three studies, (b) the individuals were not measured at the same ages, (c) there was some attrition due to death and relocation, (d) the same scales were not used at every occasion, and (e) the same items were not presented to every individual even when the same test was administered. To deal with these issues each of the models that follow are estimated using a variation of Maximum-Likelihood Estimation (MLE) based on high-dimensional integration under various assumptions about the reasons for the incomplete data (see Little & Rubin, 1987; McArdle, 1994).

In most cases here the reason a participant does not have a score on a specific item at a specific occasion was largely dependent on the investigators plan. For this reason, this form of incomplete data is entirely unrelated to the score they would have received and no statistical correction is needed (i.e., Missing Completely at Random, MCAR). In many cases, the reason the data are missing is directly related to the score, such as not being given certain test items that seemed too difficult, and corrections based on the data are needed (i.e., Missing at Random, MAR). In some cases the reason for incomplete data is less clear, such as when the individuals dropped out of the study at some point in time (e.g., After age 29, the attrition was >50% in the Bradway-McArdle study), and other variables may be needed to account for selection effects. The deal with these problems we fit all models with MLE-MAR estimation.

Initial Estimation of IRT scores

In the LIRT approach described above the IRT model (Eq. [6]) is used as the first-order of measurement and the longitudinal growth curve (Eq. [1] and [4]) can be used at the second-order – i.e., the “curve of factor scores” model, One practical way to start this analysis is to estimate a Rasch scoring table which is invariant over time. As a simple first approximation we can fit an IRT model to the available data at each occasion and then use the separate occasion item estimates to build up a scoring table for the conversion of the items to common composites. Joint maximum likelihood (JML) estimation of Rasch scores is implemented in WinSTEPS (Wright & Stone, 1979) and this creates estimates by iteratively alternating between item and person parameters, treating the other as fixed. This first stage may also be improved by using all the available data at all occasions for all persons (see Appendix Script 1a),

It has recently been recognized that all IRT models can also be reformulated as nonlinear mixed effects models (e.g., Rijmen, Tuerlinckx, De Boeck, & Kuppens, 2003). One common approach to fitting these models uses Marginal Maximum Likelihood (MML) using classic multi-dimensional integration, and typically relies on a design matrix used to select the appropriate item for comparison with the latent trait in building up the likelihood function (e.g., Smits, De Boeck, & Verhelst, 2003; De Boeck & Wilson, 2004; Sheu, Chen, Su, & Wang, 2005). However, the problems posed here are of substantially larger magnitude (e.g., 224 items), and alterations of these programs without design matrices are needed (see the NLMIXED program with ARRAYs in Script 1b).

This simple IRT approach with longitudinal data ignores several dependencies within persons over time. To account for these dependencies, we might create a separate dimension for each occasion, or facet, still requiring item invariance. The resulting person trait estimates can then be considered as observed data at each occasion for other longitudinal models (e.g., LGM-NLMIXED; Script 2). Of course, there are now a variety of elegant statistical and computational procedures for MML estimation of the parameters of latent-growth mixed-effect multi-level models with MAR incomplete data (i.e. SAS MIXED and NLMIXED, Singer, 1998; Littell et al, 1998; Verbeke & Molenberghs, 2000; S-Plus, Pinherio & Bates, 2000; MIXREG, Hedeker & Gibbons, 1997). These programs are practical in their ease of representing different models for the basis function (i.e., exact ages, non-linear curves, free basis parameters; McArdle & Bell, 2000; Verbeke & Molenberghs, 2000).

Simultaneous Estimation with MLE and MCMC

The LIRT models conceptualized here requires the assumptions that (1) the item are measuring a unidimensional construct, (2) the item difficulty is invariant with respect to time/age, (3) the items are equally discriminating and this discrimination does not change across time/age. Violations of any assumptions could lead to fundamentally incorrect conclusions regarding the within-person changes and between-person differences in change. Thus, estimation where we ignore the person dimension is likely to lead to poor estimates of growth and change.

To solve some of these problems we consider the entire model, from Eq. [1] to [6], to be a unitary model for the longitudinal items and estimate the parameters simultaneously – i.e, a “curve of factor scores” model. The primary advantage of a simultaneous analysis of the IRT-LCM is that we do not need to make a separate estimation of the LIRT score for each occasion, and this in turn should minimize the within-person dependence created by ignoring subjects in a two-stage approach. There is a possible gain in statistical efficiency from using the simultaneous approach, and the result should be more precise estimates and hypothesis tests. In practice, the first stage estimates may best be used as “starting values” for the more comprehensive simultaneous solutions.

Other researchers have shown how to deal with the complexities of fitting a simultaneous model of this type using high dimensional integration (e.g., Ferrando, 2002; Feddag & Mesbah, 2005), but the number of items and incompleteness we consider here far exceeds anything discussed in this previous literature. As a result, differences due to the different computer programs, time intervals chosen, and MAR assumptions may be important considerations in further data analysis. Once again, we can employ the MLE based programs, now with IRT and LCM combined, but once again the problems posed here are of substantially larger magnitude (e.g., up to 224 items at up to 16 occasions), and alterations of the typical programs are needed (NLMIXED+ARRAYs, Script 3). Good initial starting values are crucial to the stability of this approach (McArdle & Wang, 2007).

Recent work has also shown how the latent curve models described here can be fitted using Bayesian inference and a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithmic approach (e.g., WinBUGS, Congdon, 2003; Gelman & Meng, 2004; McArdle & Wang, 2007; Wang & McArdle, 2008; Zhang, Wang, Hamagami & McArdle, 2007). One purpose of the MCMC approach is to approximate a marginal posterior estimate without using an intractable multi-dimensional numerical quadrature method (see Brooks, 1998; Jackman, 2000). A Gibbs sampling algorithm is repeatedly used to generate a sequence of samples from the posterior joint probability distribution of model parameters. Good starting values are useful here as well because, at each MCMC iteration, the sampling of a parameter is generated given the previous posterior instance of all other model parameters and data. After a sequence of samples is generated for each parameter, an average of samples is obtained as the posterior estimate of the given model parameter. Numerous theoretical diagnostics techniques have been proposed in the past (Brooks & Roberts, 1996;Gelman & Rubin, 1992) for the convergence decision. In practice, visual inspections of the trace of sequentially sampled posterior parameter estimates are needed to examine whether the Markov chain reaches stability. A script for WinBUGS using a Bayesian approach to MCMC estimation is also presented in Appendix (Script 4).

RESULTS

Initial First-Stage Item Response Estimation

To initially represent the outcomes of these LIRT analyses, we estimated ability scores (g[t]) (using WinSTEPS and NLMIXED, Scripts 1) as a simple function of the items administered at each occasion and the total number of correct and incorrect responses, ignoring the age at measurement. Although these initial Rasch estimates are likely to be biased away from the mean (i.e., JML), these initial estimates raise a number of important empirical issues. For example, these theoretical scores can be scaled in many ways, and here we chose a logit metric to reflect linear probability changes, and defined so the average of the item difficulties is zero (i.e., ∑βι=0).

After this calculation, the Vocabulary estimates for each person was plotted against the persons’ age at testing in the life-span trajectory plot, displayed as Figure 2a. A corresponding plot of the Memory ability estimates against the participants’ age at testing is shown in Figure 2b. In an important sense, these initial estimates are a first estimate of the key longitudinal data originally desired. That is, the life-span trajectories are now represented for each person and the variable plotted, under the Rasch model theory, has the same interpretation at ages ranging from 2 to 75. These scores rise rapidly through childhood and adolescence, flatten out through adulthood, and there are substantial individual differences in both Vocabulary and Memory.

Figure 2.

Longitudinal plots of Rasch estimated person abilities against age for (A) Vocabulary and (B) Memory abilities.

Simultaneous Longitudinal Item Response Models

A simultaneous LIRT solution was estimated for the models above and the results are listed in Table 3 for Vocabulary and Table 4 for Memory. It is known that this simultaneous model requires a numerical constraint typically placed on the intercept of the intercept component in second-order growth curves (see McArdle, 1988, 1989; Hancock et al, 2001; Leite, 2007), and this constraint is imposed here. The MML estimation using NLMIXED (Script 3) took far longer than expected to carry out the numerical calculations so these results are incomplete and are not presented. (As pointed out by a reviewer, this failure to converge requires further investigation). In contrast, the MCMC estimation using WinBUGS (Script 4) was far more reasonable in terms of the computer time required for each iteration -- It was reasonable to run over 20,000 iterations for each model (i.e., 5,000 burn-in iterations, 10,000 runs, and an additional 5,000 to describe the converged estimates), and to start the estimation from three disparate starting points (even using different computers). The summary of numerical results using this Bayesian estimation approach is presented in the tables where the summary information about each parameter is listed -- including the mean of estimates, 95% credible interval, and Deviance Information Criterion (DIC, see Congdon, 2003; Speiglehalter et al, 2004).

Table 3.

Vocabulary Parameter Estimates and Fit Statistics for Age-based Latent Growth Models from Simultaneous Bayesian Estimation (using WinBUGS)

| V0b: Level Only Baseline |

V1b: Exponential Growth |

V2b: Dual Exponential Growth |

V3b: Dual Exponential with Gender |

V4b: Dual Exponential with Sample |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Fixed Effects | |||||

| Level Mean ν00 | =0 | =0 | =0 | =0 | =0 |

| Slope Mean ν10 | -- | 4.61* (4.47,4.78) |

4.98* (4.72,5.25) |

4.96* (4.73,5.19) |

4.98* (4.70,5.30) |

| Growth Rate πg | -- | .131* (.127,.136) |

.123* (.117,.130) |

.124* (.119,.129) |

.125* (.120,.131) |

| Decline Rate πd | -- | =0 | .001* (.001,.002) |

.001* (.0006,.002) |

.001* (.0003,.002) |

|

| |||||

| Level on Gender γ01 | .01 (−.20,.21) |

-- | |||

| Slope on Gender γ11 | −.11 (−.28,.06) |

-- | |||

| Level on BMW γ02 | -- | −.65* (−.90,−.40) |

|||

| Slope on BMW γ12 | -- | −.08 (−.34,.19) |

|||

| Level on GCS γ03 | -- | −.47* (−.66,−.26) |

|||

| Slope on GCS γ13 | -- | −.10 (−.33,.13) |

|||

|

| |||||

| (b) Random Effects | |||||

| Error Deviation σe | 2.34* (2.22,2.47) |

.40* (.36,.43) |

.40* (.37,.43) |

.40* (.37,.43) |

.40* (.37,.43) |

| Level Deviation σ0 | 1.00* (.85,1.15) |

.98* (.90,1.06) |

.98* (.90,1.06) |

.98* (.90,1.06) |

.97* (.89,1.05) |

| Slope Deviation σ1 | -- | .65* (.59,.72) |

.70* (.63,.78) |

.70* (.63,.78) |

.69* (.62,.78) |

| Covariance ρ01 | -- | −.15* (−.24,−.06) |

−.15* (−.25,−.06) |

−.15* (−.26,−.06) |

−.16* (−.26,−.07) |

|

| |||||

| (c) Goodness-of-Fit | |||||

| DIC | 71660 | 70042 | 69998 | 70011 | 70012 |

| Parameters | 3 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 11 |

Notes: (1) Data D=2507 based on maximum N=419, T=13, I=99; (2) Cell entries include MLE and 95% Credible Intervals in parentheses; (2) ‘*’ indicates a significant parameter at .05 level; (3) ‘--’ indicates that a model does not include a parameter; (4) Age was recentered at 10 years; (4) Final Information matrix was not Positive Definite in Linear Model; (5) Quadratic and Linear Models did not converge.

Table 4.

Memory Span Parameter Estimates and Fit Statistics for Age-based Latent Growth Models from Simultaneous Bayesian Estimation (using WinBUGS)

| M0b: Level Only Baseline |

M1b: Exponential Growth |

M2b: Dual Exponential Growth |

M3b: Dual Exponential with Gender |

M4b: Dual Exponential with Sample |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Fixed Effects | |||||

| Level Mean ν00 | =0 | =0 | =0 | =0 | =0 |

| Slope Mean ν10 | -- | 3.42* (3.22,3.61) |

4.18* (3.91,4.20) |

4.19* (3.77,4.60) |

4.20* (3.86,4.57) |

| Growth Rate πg | -- | .213* (.205,.225) |

.186* (.172,.197) |

.186* (.175,.201) |

.180* (.170,.185) |

| Decline Rate πd | -- | =0 | .007* (.006,.008) |

.007* (.005,.009) |

.007* (.006-,.009) |

|

| |||||

| Level on Gender γ01 | −.25 (−.48,.02) |

||||

| Slope on Gender γ11 | .13 (−.05,.33) |

||||

| Level on BMW γ 02 | −1.04* (−1.43,−.66) |

||||

| Slope on BMW γ12 | −.13 (−.46,.21) |

||||

| Level on GCS γ 03 | −.52* (−.75,−.28) |

||||

| Slope on GCS γ13 | .39* (.13,.62) |

||||

|

| |||||

| (b) Random Effects | |||||

| Error Deviation σe | .84* (.77,.92) |

.38* (.29,.46) |

.34* (.25,.43) |

.34* (.24,.43) |

.35* (.26,.45) |

| Level Deviation σ0 | .97* (.88,1.06) |

1.45* (1.34,1.57) |

1.46* (1.34,1.58) |

1.45* (1.34,1.57) |

1.40* (1.29,1.51) |

| Slope Deviation σ1 | -- | .48* (.41,.56) |

.59* (.50,.69) |

.59* (.49,.70) |

.57* (.47,.68) |

| Covariance ρ01 | -- | −.06* (−.18,−.06) |

−.01 (−.16,.14) |

.01 (−.16,.17) |

.01 (−.14,.15) |

|

| |||||

| (c) Goodness-of-Fit | |||||

| DIC | 24090 | 20989 | 20905 | 20940 | 20904 |

| Parameters | 2 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 11 |

Notes: (1) Data D=3107 based on maximum N=416, T=16, I=76; (2) Cell entries include MLE and 95% Credible Intervals in parentheses; (2) ‘*’ indicates a significant parameter at .05 level; (3) ‘--’ indicates that a model does not include a parameter; (4) Age was recentered at 10 years.

Fitting Alternative Change Models

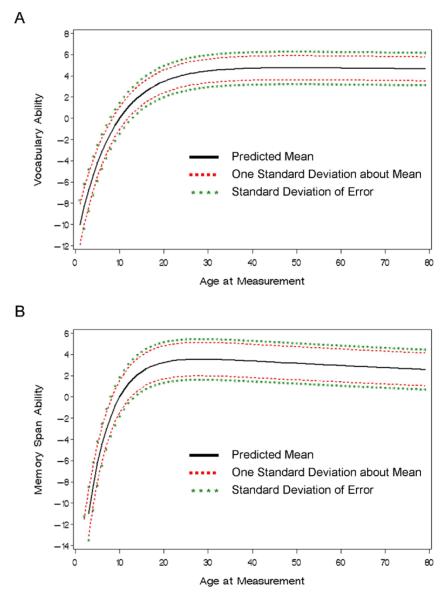

Several growth models (i.e., level only, exponential, dual exponential) were fit as the second-level LCM model in the simultaneous estimation of IRT-growth models. The parameters (p) estimated and fit statistics are presented in the first three columns of Table 3 for a series of simple growth models fit to the item-level vocabulary. The initial level only model (V0) gives a baseline for evaluating fit (DIC=71660) and includes two growth parameters (σ0 = 1.00, and σe = 2.34). The mean of the latent level was fixed for identification purposes (μ0 = 0). Both linear models and quadratic models based resulted in serious convergence problems. In contrast, the single exponential model (V1) fit much slightly better than the level only model (DIC=70042, Δp=4). Here the slope mean (μ1 = 4.61) and the “growth” rate (πg=.13) indicating a rapid early growth from childhood to early adulthood. The level and slope variances and their covariance (σ0=0.98, σ1=0.65, σ01= −0.15) show significant variation in vocabulary at age 10 and significant variation in individual changes. Furthermore, children who had a greater level of vocabulary ability at age 10 tended to have a slower rate of change. The dual exponential model (V2) fit slightly better than the single exponential model (DIC = 69998, Δp = 1), and the “decline” rate (πd=.001) indicates a small but significant decline in ability in through adulthood. As with the exponential model, the average rate of change was positive (μ1= 4.98)and there was significant variation in the level (σ1=.98) and slope (σ1= .70) and their covariance (σ01= −.15) was also significant. The expected mean (and deviations) of the age-based latent curve of Vocabulary is displayed in Figure 3a.

Figure 3.

Latent Growth Curve Model expected group trajectories based on the dual exponential model with one standard deviation around the mean for (A) Vocabulary and (B) Memory abilities.

The same sequence of IRT-growth models was applied to the Memory Span items, and the dual exponential model also best represents the longitudinal data (Table 4). The level only model (DIC=24090) provided a baseline for comparison and two growth parameters, the variation of the level (σ0= .97) and residual (σe= .84). The exponential model was an improvement over the level only model (DIC=20989, Δp= 4). The mean slope was positive (μ1=3.42) and the growth rate was positive (πg =.21) and larger (i.e., faster) than Vocabulary. As with Vocabulary, there was significant variation in the level (σ0=1.45) and slope (σ1=.48), but their covariance (σ01=−.06) was non-significant. Next, a dual exponential growth model was fit as the second-level growth model and the fit was subsequently improved (DIC=20905, Δp=1). The mean slope (μ1= 4.18), growth rate (πg =.19) and decline rate (πd =.007) were all positive and significant, and this describes a latent curve with a fast rate of growth during childhood and adolescence and a marked decline through adulthood. There was significant variation in the level (σ0=1.46) and slope (σ1=.598), but their covariance (σ01=−.01) was non-significant. The mean (and deviation) of the latent curve of Memory is displayed in Figure 3b.

These latent curve estimates of the dual exponential growth model obtained for Memory were quite different from those for Vocabulary. The dual exponential model has a marked acceleration through childhood and adolescence as in the Vocabulary model, but as young adulthood is reached the function reaches its maximum and begins a decline. While it is compelling to state that the decline in Memory is more pronounced than that of Vocabulary, we cannot compare them directly because they are not in the same scale of measurement.

Including Predictors of Change

In the next set of models (V3 and M3) we introduced sex differences in the LIRT levels and slopes. The IRT-growth models with a dual exponential basis were refit with Gender (coded − ½ for female and ½ for males) as a predictor of the level and slope. For the Vocabulary and Memory span data, Gender was a non-significant predictor of the level and slope. To investigate the potential differences between our three groups, the trajectories were compared by including two dummy codes to compare the levels and slopes of the BML and GCS samples to the BGS sample (see Figure 4). The mean level (at age 10) of the BML and GCS samples was slightly lower than the mean level of the BGS sample on Vocabulary. For Memory span, the BMW and GCS samples had lower mean performances at age 10 compared with the BGS sample, but the GCS sample had a slightly greater rate of change than the BGS sample. It would be useful at this point to more fully evaluate the invariance of the measurement model over the multiple groups, but we recognize these data are limited in this respect.

Figure 4.

Expected group growth curves of (A) Vocabulary and (B) Memory abilities for the three independent study groups – the Berkeley Growth Study (BGS), the Guidance Control Study (GCS), and the Bradway-McArdle Longitudinal Study (BML).

As these new growth charts show, the intellectual abilities underlying Vocabulary and Memory rise rapidly throughout childhood, peak in early adulthood, and decline at a very slow rate, if at all. The use of combined data increased the precision of most tests (McArdle et al, 2001), and some significant but small differences were found between the separate studies (BGS, GCS, and BML). However, individual differences in the intercepts (at age 10) and subsequent changes were not related to group differences in gender. Of course, this sets the stage from the inclusion of other multilevel predictors, some of which differ over these samples (see Grimm & McArdle, 2007).

DISCUSSION

Summary of Results

The basic requirements of meaningful and age-equivalent measurement models are a key problem in the behavioral sciences (see Burr & Nesselroade, 1990; Fischer & Molenaar, 1995). The possibilities for a standard longitudinal measurement analysis were initially limited here by the complex longitudinal data collection (Jones et al, 1971). The classical solutions based on simple or complex rescoring were not used and have generally not been considered satisfactory to a wide research audience because of their ad hoc nature. Although not emphasized here, a full-information SEM approach based on using multiple indicators at the scale level failed to be estimable due to large amounts of incomplete data (see McArdle & Nesselroade, 2003). In contrast, the simultaneous estimation approach for a combined LIRT-growth model was able to account for the dependencies (longitudinal aspect) of the data. This method allowed us to consider changes over age in the same constructs for a longer span of time than any previous longitudinal study of cognitive aging.

To many substantive researchers this kind of mixed-battery data collection is far better than a strict adherence to repeated measures because of age-appropriateness, improved batteries, and so on. The subsequent IRT-growth analyses provided (a) a relative scaling of each item for Vocabulary and Memory as if everyone had taken all items on all scales, (b) ability estimates for participants at each occasion of measurement, and (c) parameters of average growth and of between-person differences in growth. Of course, it is also important to verify these results using other datasets where the scales are constant. For example, the loss of memory from adolescence to your adulthood is coincident with the changing scales, so the accuracy of this decline requires further verification (see McArdle et al, 2002). The IRT-growth solution used here may reflect the best case scenario because it solves one of the key problems of changing measures of repeated constructs. An ancillary result of this analysis is the optimal selection of a shortened LIRT (e.g., 24 items) with fairly well spaced item difficulty (available upon request). It is also important to consider checking the adequacy of the pooling of data by further sensitivity analyses – i.e., considering the results when one or more sub-samples of people are treated as missing.

Simultaneous vs. Two-Stage Estimation

This simultaneous estimation approach used here is thought by many researchers to be the optimal way to model longitudinal item-level data in which systematic growth is expected. However, some viable alternative estimation approaches may be more practical and provide additional information not easily obtainable in the simultaneous estimation approach. One alternative we mentioned is a two-stage approach in which ability estimates for each person at each occasion are estimated using an item response model. In the second step, the ability estimates obtained from a first step can be used as observed data and modeled using growth curve analysis. This alternative two-stage estimation was not pursued here because it was considered less optimal due to the longitudinal dependencies within person. Some problems of factor score estimation (e.g., Croon, 2002) can be overcome simply by using a simultaneous estimation of the joint set of parameters (as in Tables 3 and 4). However we do not want to overlook several practical advantages. First, the fit of items/people to the specific item response model can be evaluated in a standard IRT framework. Second, the ability estimates from the first step are easily plotted (e.g., as in Figure 2), and this can allow the researcher to check for outliers or unusual observations and consider the shape of development. Third, this simpler approach cuts down on the computational complexity and the amount of estimation time required. These are all practical issues worthy of further investigation.

Longitudinal Item Response Modeling Limitations

Of paramount importance here is our lack of ability to examine the assumption of metric factorial invariance over occasions (i.e., Λ[t]=Λ[t+1]?; McArdle & Nesselroade, 1994), and we were limited in what we could accomplish here. When this kind of restrictive model of “changes in the factor scores” among multiple variables provides a reasonable fit to the data, we have evidence for “dynamic construct validity” (as in McArdle et al, 1998; McArdle, 2005). Unfortunately, when the data are less than complete, or reflect non-overlapping scales, we lose some or most of the statistical power of such tests. Due to the changing measures we basically had to assume but not test invariance of the construct over time in order to proceed with our calculations. To make this a more reasonable analysis, we selected narrowly defined abilities of Vocabulary and Memory Span, and considered these as part of a larger “universe of items” (Gullicksen, 1950). A more complete consideration of metric versus configural invariance with different loadings for different items would be possible in more carefully designed item selections. In general, we do expect the LIRT method can be operationalized in studies with clearly defined constructs over repeated testings.

As we have shown using MCMC estimation, it is now possible to fit models with simultaneous estimation of item characteristics and higher-order factors, including changes over time (e.g., Hamagami, 1998; Jamssen, Tuerlinckx, Meulders & De Boeck, 2004; Fox & Glas, 2001; Rijmen et al, 2003, 2005; Ram et al, 2005). It also follows that a simultaneous IRT-LCM model might increase accuracy from different stages of analysis. Unfortunately, this model could not be fitted using the standard ML estimation based on high dimensional integration, and this may be due to the size of our problem and/or the lack of overlap in the items (e.g., Table 1). The large amount of incomplete information made it impossible to carry out SEM models at the scale level. The standard IRT-LCM calculation also made it difficult to fit a simultaneous growth-item model using standard MLE. In contrast, the MCMC approach to these problems used here highlights a practical solution that others may find useful when faced with these kinds of longitudinal models.

Issues for Future Longitudinal Studies

A set of theoretical and practical issues have emerged from these longitudinal analyses:

Contemporary data analysts need not simply rephrase substantive questions about development to deal with incommensurate measures (growth ~ regression). The models that are used for data analysis should drive the data collection, but this is not always the case. While classic methods such as the factor-growth models as applied in standard SEM programs were limited here by the lack of overlap of the scales, the item intensive IRT-growth analyses presented here were successful. The subsequent mixed-effects analyses demonstrate the possibility of measuring and evaluating growth and change in the same constructs over many ages using non-repeated or changing measures.

In theory it is not necessary or desirable for future longitudinal studies to require exactly the same measures from one occasion to the next. As shown here, there are several contemporary techniques based on latent variables for dealing with repeated constructs without exactly repeated measures. This means a scale should not simply be repeated because it was given before. Instead scale alteration over time should be designed to match reasonable substantive goals (i.e., age-appropriateness) and not repeat items or scales that are irrelevant.

Planning for overlapping scales or items within and between occasions is essential. It is clear that much can be accomplished by carrying over of some scales or items from one occasion to the next to facilitate future analysis. If the practical problems of calibration at the scale and item level are recognized at the design stage, a variety of future analyses will be feasible. It is essential to study the linkage features of measurement in all longitudinal designs.

Although not emphasized here, the IRT calibration does not require longitudinal data. Instead, measurement calibrations at the scale and item level can and should be completed in auxiliary studies outside the constraints of longitudinal studies. This encourages increased accuracy in scaling results based on much larger and wider-range cross-sectional studies. But “Can we just take the scoring system from some larger IRT calibration studies and use it with new occasions and people?” One unique aspect of the longitudinal data demonstrated here is the increased precision of the random effects from the simultaneous LIRT model fitting. However, we may not always be able to benefit from item model fitting and scale model fitting within the same study. Future longitudinal studies can benefit from considering many different approaches to cross-battery calibrations.

Pooling Data with some Overlapping Measures is a Powerful Idea. The attempt to use all available information from any person measured on any of the variables of interest in a study can lead to increased multivariate power and precision (e.g., McArdle, 1994). Of course, biases can emerge when subgroups of persons within distinct groups should not be considered from the same population, and without overlapping information we may not realize these problems exist at all. We need to examine the assumptions of pooling group data whenever such data are available.

The results for LIRT multiple group pooled data approximations presented here may be emphasized in different ways by different researchers. These differences represent potentially important theoretical and practical choices for future longitudinal researchers.

Acknowledgments

John J. McArdle is supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (AG02695, AG04704, and AG07137). Kevin J. Grimm was supported in part by a National Institute on Aging Training Grant NIA T32 AG20500-01 and an Institute of Education Sciences Training Grant received by the University of Virginia when he attended the University of Virginia. Ryan P. Bowles was supported by National Institute on Aging Training Grant NIA T32 AG20500-01 when he attended the University of Virginia.

This work is dedicated to our late co-author, Bill Meredith, who had the original idea for the LIRT type analysis. Of course, these analyses would not have been possible without the cooperation of the participants of the Bradway-Longitudinal Study and the Inter-Generational Studies. The extensive recoding of the item level was carried out by the second author in collaboration with Ms. Anna Hammarskjold. We also thank our colleagues John L. Horn, John R. Nesselroade, Karen M. Schmidt, and Carol A. Prescott for their assistance in this research and for their comments on drafts of this paper. Early versions of this paper have been presented at the Society of Multivariate Experimental Psychology, University of Virginia (October, 2002), at the Working Conference on The Future of Longitudinal Studies, Institute of Human Development, University of California, Berkeley (March 2003), and at the Annual Meeting of the Gerontological Society of America, San Diego (November 2003).

Appendix

1a: WINSTEPS input script for initial Rasch model fitting

Winsteps Script for PCM Model &INST TITLE=‘Vocabulary Analysis’ DATA=LIRT_Vocab_Items.txt ITEM1=20 NI=278 PTBIS=Y CODES = 012 GROUPS= 0 &END

1b: Alternative SAS PROC NLMIXED Script for Initial Rasch model fitting

TITLE2 ‘Initial Rasch Model for First Occasion’;

PROC NLMIXED DATA = LIRT_Vocab_Items_224 (WHERE=(Time=1))

METHOD=GAUSS TECHNIQUE=NEWRAP NOAD QPOINTS=20;

ARRAY beta[224] beta1-beta224;

diff = gscore − beta[item_num];

p=1/(1+EXP(−diff));

MODEL item_mem ~ BINARY(p);

RANDOM gscore ~ NORMAL([0], [sigma_g*sigma_g]) SUBJECT = id;

PARMS s_g=1 beta1-beta224=.001;

ESTIMATE ‘variance’ sigma_g*sigma_g;

PREDICT p OUT=Vocab_Pred_Prob;

PREDICT gscore OUT=Vocab_Pred_Parm_Person;

ODS OUTPUT ParameterEstimates=Vocab_Pred_Parm_Item;

RUN;2: SAS PROC NLMIXED Script for Dual Exponential Growth Model of estimated Rasch Scores

TITLE2 ‘Dual Exponential Model fitted to estimated scale scores’;

PROC NLMIXED DATA = LIRT_Vocab_Scale;

Yt = g0 + g1 * At ;

At=(EXP(−pi_d*(age-10)) − EXP(−pi_g*(age-10)));

MODEL measure ~ NORMAL(Yt, V_e);

RANDOM g0 g1 ~ NORMAL([nu_0, nu_1],

[V_0, C_01, V_1])

SUBJECT = id out=LIRT_Vocab_Growth_estimate;

PARMS nu_0=0 nu_1=1 pi_g=.10 pi_d=0.01

V_e=1 V_0=5 V_1=1 C_01=.01;

RUN;3: SAS PROC NLMIXED Script for Simultaneous LIRT Approach

TITLE2 ‘Fitting the item-growth model to the longitudinal item data’;

PROC NLMIXED DATA = LIRT_Vocab_Items_224

METHOD=GAUSS TECHNIQUE=NEWRAP NOAD QPOINTS=20;

ARRAY beta[224] beta1-beta224;

ARRAY g[16] g1-g16;

ARRAY u[16] u1-u16;

g[occ] = g_0 + g_1*At + u[occ];

At =EXP(−pi_d*(age-10)) − EXP(-pi_g*(age-10));

diff = g[occ] − beta[item_num];

p=1/(1+EXP(−diff));

v_0 = sigma_0*sigma_0;

v_1 = sigma_1*sigma_1;

v_u = sigma_u*sigma_u;

c_01 = rho_01*sigma_0*sigma_1;

MODEL item_mem ~ BINARY(p);

RANDOM g_0 g_1 u1 u2 u3 u4 u5 u6 u7 u8 u9 u10 u11 u12 u13 u14 u15 u16 ~

NORMAL([0,nu_1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0],

[v_0,

c_01, v_1,

0, 0, v_u,

0, 0, 0, v_u,

0, 0, 0, 0, v_u,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, v_u,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, v_u,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, v_u,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, v_u,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, v_u,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, v_u,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, v_u,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, v_u,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, v_u,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, v_u,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, v_u,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, v_u,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, v_u])

SUBJECT = id;

PARMS nu_1=1 sigma_0=1 sigma_1=1 rho_01=.001 sigma_u=2

beta1-beta224=1 pi_g=.15 pi_d=0.001;

ESTIMATE ‘level variance’ sigma_0*sigma_0;

ESTIMATE ‘slope variance’ sigma_1*sigma_1;

ESTIMATE ‘leve-slope covariance’ rho_01*sigma_0*sigma_1;

ESTIMATE ‘unique variance’ sigma_u*sigma_u;

PREDICT p OUT=Pred_Prob;

PREDICT gscore OUT=Vocab_Pred_Parm_Person;

ODS OUTPUT ParameterEstimates=Vocab_Pred_Parm_Item;

RUN;4: WinBUGS Script for Simultaneous One-Stage LIRT Approach

Model Dual Exponential with PCM

#variable specification

gscore[N,T] person trait levels

beta[I] item difficulties

gamma[J] step difficulties

tau precision for person distribution

sigma2 variance of person distribution

p[N,I,T,J] category probabilities

x[N,I,T] item responses

z[N,I,T,J] working matrix

#likelihood

model{

for (n in 1:N) {

for (t in 1:numobs[n]) {

for (i in 1:115) {

logit(p[n,t,i])<-gscore[n,t]-beta[i]

x[n,t,i] ~ dbern(p[n,t,i])

}

for (i in 116:224) {

z[n,t,i,1]<-1

pr[n,t,i,1]<-1/sum(z[n,t,i,])

log(z[n,t,i,2])<-gscore[n,t]-beta[i]-gamma[i-115]

pr[n,t,i,2]<-z[n,t,i,2]/sum(z[n,t,i,])

log(z[n,t,i,3])<-2*(gscore[n,t]-beta[i])

pr[n,t,i,3]<-z[n,t,i,3]/sum(z[n,t,i,])

x[n,t,i] ~ dcat(pr[n,t,i,])

}

gscore[n , t] ~ dnorm(mu[n , t],tauy)

mu[n,t] <- nu[n,1] +nu[n,2]* At

At= (exp(−1*pid*(age[n,t]-10)) − exp(−1*pig*(age[n,t]-10)))

}

}

#priors

for (i in 1:224) {

beta[i] ~ dnorm(0,1.0E-6)

}

for (i in 1:109) {

gamma[i] ~ dnorm(0,1.0E-6)

}

tauy ~ dgamma(0.001,0.001)

for( n in 1 : N ) {

nu[n,1:2]~dmnorm(munu[1:2],taunu[1:2,1:2])

}

munu[1]<-0

munu[2]~dnorm(0, 1.0E-6)

taunu[1:2,1:2]~dwish(R[1:2, 1:2],2)

sigma2nu[1:2, 1:2]<-inverse(taunu[1:2,1:2])

sigmay <- 1 / sqrt(tauy)

pid~dnorm(0,1.0E-6)

pig~dnorm(0,1.0E-6)

}

NOTE: Data entry in vector form needs to followREFERENCES