Abstract

The globus pallidus plays a central integrative role in the basal ganglia circuitry. Morphological studies have revealed a high level of GABA and GABAA receptors in the globus pallidus. To further investigate the effects of endogenous GABAA neurotransmission in the globus pallidus of normal and parkinsonian rats, in vivo extracellular recording and behavioral tests were performed in the present studies. In normal rats, micro-pressure ejection of GABAA receptor antagonist gabazine (0.1 mM) increased the spontaneous firing rate of pallidal neurons by 28.3%. Furthermore, in 6-hydroxydopamine parkinsonian rats, gabazine increased the firing rate by 46.0% on the lesioned side, which was significantly greater than that on the unlesioned side (21.5%, P < 0.05), as well as that in normal rats (P < 0.05). In the behaving rats, unilateral microinjection of gabazine (0.1 mM) evoked consistent contralateral rotation in normal rats, and significantly potentiated the number of apomorphine-induced contralateral rotations in parkinsonian rats. The present electrophysiological and behavioral findings may provide a rational for further investigations into the potential of pallidal endogenous GABAA neurotransmission in the treatment of Parkinson's disease.

Keywords: globus pallidus, GABAA receptor, Parkinson's disease, single unit recording

Introduction

The globus pallidus in rodents, equivalent to the external globus pallidus in primates, is located in the central position of the basal ganglia circuit (Smith et al., 1998; Bolam et al., 2000). It mainly receives GABAergic inputs from the striatum and local axon collaterals, and glutamatergic afferents from the subthalamic nucleus (Kita and Kitai, 1991; Kita, 1992; Parent and Hazrati, 1995; Kita et al., 1999). In turn, the globus pallidus sends its GABAergic output to all the basal ganglia nuclei including the subthalamic nucleus, the striatum, the entopeduncular nucleus and the substantia nigra (Bolam et al., 2000; Parent et al., 2000; Kita and Kita, 2001). There is much evidence that the globus pallidus plays an important role in normal movement regulation and in basal ganglia movement disorders, such as Parkinson's disease (Mink, 1996; Bolam et al., 2000). For example, the firing rate of the globus pallidus neurons decreased in parkinsonian patients, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) primate model of Parkinson's disease and 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) parkinsonian rats (El-Deredy et al., 2000; Heimer et al., 2002; Soares et al., 2004; Starr et al., 2005; Breit et al., 2007). In addition to the changes in firing rate, the firing patterns of the globus pallidus were found to be more bursty (Filion and Tremblay, 1991; Ni et al., 2000) and displayed an increase in synchronous rhythmic activity (Bergman et al., 1998; Magnin et al., 2000; Raz et al., 2000; Wichmann and Soares, 2006) under parkinsonian state.

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter used in the globus pallidus and exerts its function through two receptor subtypes: GABAA and GABAB receptors (Oertel et al., 1984; Zhang et al., 1991; Bolam and Smith, 1992; Shink and Smith, 1995). Morphological studies have shown that both GABAA and GABAB receptors are expressed in the globus pallidus (Bowery et al., 1987; Wisden et al., 1992; Peng et al., 2002). The inhibitory postsynaptic action of GABA is primarily mediated through GABAA receptors (Macdonald and Olsen, 1994; Sieghart, 1995). A line of evidence indicated that there is a close relationship between GABA or GABAA receptors and Parkinson's disease. For example, the expression of GABAA/benzodiazepine receptors in the rostral part of the globus pallidus significantly decreased in unilateral or systemic MPTP-treated monkeys (Robertson et al., 1990; Calon et al., 1995). Similarly, the messenger RNA levels of GABAA receptors decreased in the globus pallidus of 6-OHDA-lesioned rats and parkinsonian patients (Pan et al., 1985; Griffiths et al., 1990; Chadha et al., 2000). However, by using microdialysis, the release of GABA was observed to be increased in the globus pallidus of parkinsonian animals (Robertson et al., 1991; Ochi et al., 2000; Schroeder and Schneider, 2002). Consistently, an increase of GAD67 mRNA, the rate-limiting enzymes of GABA synthesis, has been reported in the globus pallidus of nigrostriatal lesioned rats (Kincaid et al., 1992; Soghomonian and Chesselet, 1992; Billings and Marshall, 2004) and MPTP-treated cats and primates (Soghomonian et al., 1994; Schroeder and Schneider, 2001; Soares et al., 2004). Thus, exploring the effects of endogenous GABAA neurotransmission controlling the activity of pallidal neurons is important for understanding the functions of globus pallidus in normal and pathological conditions. In this study, we elucidated the electrophysiological effects of gabazine, a GABAA receptor antagonist, on the firing rate of globus pallidus neurons by extracellular recordings. We also microinjected gabazine directly into the globus pallidus of unilaterally 6-OHDA-lesioned rats and normal rats to observe the behavioral effects.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult male Wistar rats, weighing 260–290 g, were used in this study. Animals were housed under a 12-h light/dark cycle with food and water available. The experiments were performed according to the University guidelines on animal ethics. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

Establishment of parkinson's disease model with 6-OHDA lesioning

Rats were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (400 mg/kg, i.p.) and placed in a stereotaxic frame (NarishigeSN-3, Tokyo, Japan). Then the scalp was shaved, swabbed with iodine and a central incision was made to expose the skull. A cranial burr hole (1 mm) was drilled into the skull over the injection site, and a microsyringe was lowered into the right medial forebrain bundle: 3.2 mm posterior, 1.5 mm lateral to the bregma, and 8.7 mm ventral to the skull surface (Paxinos and Watson, 1986). A total dose of 14.5 μg 6-OHDA hydrochloride (H4381; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in 4 μl sterile saline containing 0.01% ascorbic acid was then injected into the right medial forebrain bundle at a rate of 1.0 μl/min. The microsyringe was allowed to rest for 10 min to prevent backflow of the toxin. Rats were pretreated 30 min before the 6-OHDA infusion with 25 mg/kg desipramine to protect noradrenergic projections. Two weeks after the 6-OHDA treatments, the rats were injected subcutaneously with 0.2 mg/kg apomorphine hydrochloride (A4393; Sigma) dissolved in 0.1% ascorbated saline solution. Animals accomplishing at least 210 net contralateral rotations in 30 min were included in this study.

In vivo electrophysiological recordings

Extracellular single unit recordings were performed in rats anesthetized with urethane (1 g/kg, i.p.; supplemented as needed) and positioned in the stereotaxic frame. Body temperature was maintained at 36–38°C by a heating pad. According to the stereotaxic atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 1986), an incision was made in the scalp, the skull exposed, and a burr hole drilled in the skull.

Three-barrel microelectrodes were fastened at each end with metal tubing and prepared using a Stoelting pipette puller (Stoelt-ing Co., Wood Dale, IL., USA). They were broken to a tip diameter of 3–10 μm under the microscope. The resistance of the microelectrodes ranged from 10 to 20 MΩ. The recording electrode was filled with 0.5 M sodium acetate containing 2% pontamine sky blue. The other two micro-pressure ejection barrels connected to 4-channel pressure ejector (PM2000B; Micro Data Instrument, South Plainfield, NJ, USA) respectively contained either gabazine or vehicle (normal saline). The electrode was then placed into the globus pallidus with coordinates of 0.8–1.3 mm posterior, 2.5–3.5 mm lateral from the bregma, 5.5–7.2 mm vertical from the dura (Paxinos and Watson, 1986). Neurons were identified as pallidal on the basis of their location and electrophysiological features. Drugs were ejected onto the surface of firing neurons with short pulse gas pressure (1500 ms, 5.0–15.0 psi).

The recorded electrical signals were amplified by a micro- electrode amplifier (MEZ-8201, Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan) and displayed on a memory oscilloscope (VC-11, Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan), while being fed to an audiomonitor. The amplified electrical signals were passed through low and high pass filters into a bioelectricity signal analyzer and computer. Spike times were preprocessed online and further analyzed offline using the program of Histogram ver 1.00 (Shanghai Medical University, Shanghai, China) for spike data analysis. The firing rates were recorded in 1 s bins. Drug infusion was performed only once for each recording and a period of 30 min at least was allowed to pass before another recording in the same track.

At least 5 min stable basal firing was collected from each neuron before drug ejection onto the globus pallidus. The frequency of basal firing was determined by the average frequency of 120 s baseline data before drug administration. The maximal change of frequency within 50 s following drug application was considered as drug effect. A change of at least 20% of basal firing rate during drug application was considered significant (Querejeta et al., 2005).

Behavioral test

Firstly, the normal rats were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (400 mg/kg, i.p.) and placed in a stereotaxic frame. A guide cannula constructed from stainless steel (o.d., 0.4 mm; i.d., 0.3 mm) was implanted into the globus pallidus on the right side (1.0 mm posterior, 3.0 mm lateral from the bregma, 6.9 mm ventral from the skull surface). The cannulae were fixed to the skull with stainless steel screws and dental acrylic. Stainless steel stylets were used to keep the cannulae sealed. Following at least 3 days of recovery, the rats were tested for rotational behavior. The rats were placed in an observation cage to which they had already become habituated. Saline or 0.1 mM gabazine (0.5 μl) was microinjected into the globus pallidus in awake rats over a 2 min period. At the end of injection, the cannula was left in the globus pallidus for an additional 1 min before removal and then replaced by a stylet. Rotational behavior was recorded by a digital camera.

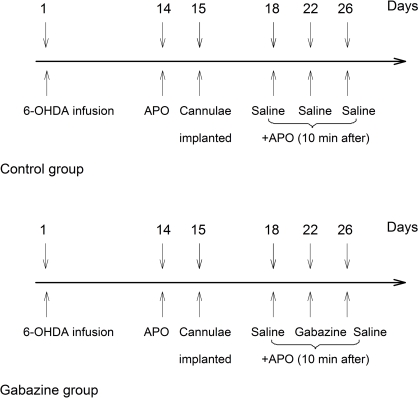

Secondly, the successful parkinsonian rats were divided into two groups. Each group contained an equal representation of good rotators (>10 rotations/min) and moderate rotators (7–10 rotations/min) in order to balance the groups based upon their average rate of rotation for the 30 min testing period. On the 15th days following 6-OHDA lesion, both groups were unilaterally implanted with stainless steel guide cannulae into the globus pallidus ipsilateral to lesioned side at coordinates mentioned above. Three days after cannulae implantation, rats in both groups were intrapallidally microinjected vehicle (0.5 μl normal saline) 10 min prior to apomorphine application (0.2 mg/kg, s.c.) as baseline scores. After the baseline scores were obtained, rats in control group were intrapallidally injected normal saline every 4th day (i.e., on the 22nd and 26th days). While in gabazine group, rats were intrapallidally injected gabazine (0.1 mM, 0.5 μl) on the 22nd days. On the 26th days, normal saline was microinjected into the globus pallidus again in this group. Ten minutes after each intrapallidal injection, apomorphine was administrated subcutaneously. The resulting contralateral rotations were counted every 10 min for 60 min. The schematic diagram (Figure 1) depicts the schedules of experiments in the two groups of animals.

Figure 1.

A schematic diagram depicted the experimental design in the present study. Numerals with the downward arrows above the line represent the days experiments were conducted. The arrows on day 1 indicate 6-OHDA infusion. The upward arrows depict the days for behavioral testing, and the drugs used.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

To identify the position of single unit recording, pontamine sky blue was ejected from the recording electrode tip by iontophoresis (10 μA, 20 min). All the rats used in electrophysiological and behavioral experiments were sacrificed and perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde solution transcardially. Brains were frozen, sectioned at 50 μm and all the recording and microinjection sites were verified under light microscope. To confirm the nigral dopaminergic degeneration, rats receiving 6-OHDA treatment were examined for immunohistochemical staining of tyrosine hydroxylase after electrophysiological and behavioral tests.

Drugs and statistics

Gabazine, 6-OHDA hydrochloride, apomorphine hydrochloride and monoclonal anti-tyrosine hydroxylase antibody were obtained from Sigma.

The data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Data analysis was performed using SPSS software. Paired t test was used to compare the difference of firing rate before and after treatment. Statistical comparisons between groups were determined with student's t test. Bivariate analyses was used to analyse the correlation between the gabazine-induced excitation and basal firing rate of pallidal neurons. The numbers of rotations were analyzed by the non-parametric one-way Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Mann-Whitney test. The level of significance was preset by using a P value of 0.05.

Results

Effects of gabazine on spontaneous firing of globus pallidus in normal rats

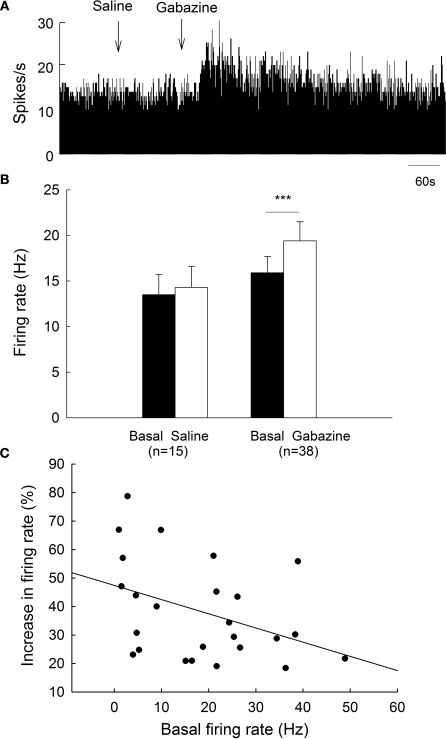

All the spikes recorded in the present study showed a biphasic positive/negative waveform, which is characteristic of type II globus pallidus neurons (Kelland et al., 1995; Ruskin et al., 1998). To clarify the effects of gabazine on globus pallidus neurons of normal rats, we monitored the spontaneous activity of 38 pallidal neurons sampled from 10 rats. The spontaneous firing rate of pallidal neurons was 15.9 ± 1.8 Hz in average. Micro-pressure ejection of 0.1 mM gabazine increased the frequency of spontaneous firing to 19.4 ± 2.1 Hz (n = 38, P < 0.001, Figures 2A,B). The average increase was 28.3 ± 3.3%, which was significantly different (P < 0.001) from that of vehicle (normal saline) injection (basal: 13.5 ± 2.2 Hz; saline: 14.3 ± 2.3 Hz; increase: 6.2 ± 1.4%, n = 15, Figures 2A,B). More than 20% increase in firing rate was observed in 25 out of the 38 neurons receiving gabazine administration (basal: 13.9 ± 2.2 Hz; gabazine: 18.3 ± 2.8 Hz; increase: 38.3 ± 3.5%, n = 25). As shown in Figure 2C, we further analyzed the correlation between gabazine-induced excitation with the basal firing rate in the 25 neurons. Although modest, there was a negative correlation (r = −0.40, P < 0.05) between these two parameters, suggesting that the neurons with slower basal firing rate are more affected by gabazine in globus pallidus.

Figure 2.

Effects of micro-pressure ejection of gabazine on the spontaneous firing of globus pallidus neurons in normal rats. (A) Typical frequency histograms showing that gabazine (0.1 mM) increased the firing rate of a globus pallidus neuron by 57.8%. (B) Pooled data summarizing the effects of gabazine and normal saline on the firing rate of globus pallidus neurons in normal rats. ***P < 0.001. (C) Correlation between the increase of firing rate and the basal firing level in pallidal neurons with more than 20% increase in firing rate.

Effects of gabazine on spontaneous firing of globus pallidus in 6-OHDA-lesioned rats

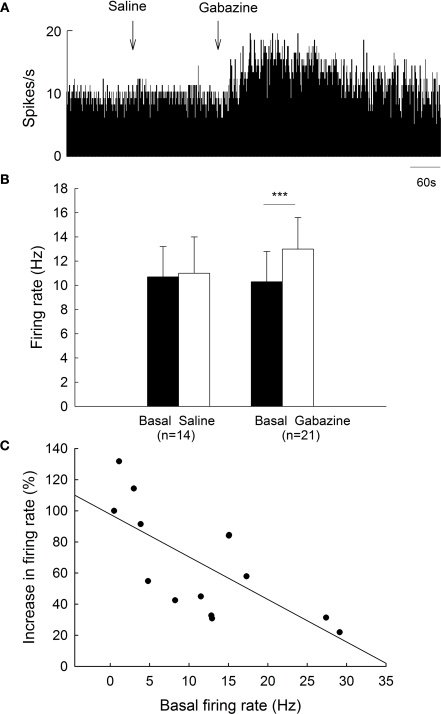

To clarify the functions of GABAA receptors on globus pallidus neurons of 6-OHDA-lesioned parkinsonian rats, we monitored the spontaneous activity of 39 pallidal neurons sampled from 10 parkinsonian rats. On the lesioned side, pallidal neurons discharged with a mean firing rate of 10.3 ± 2.5 Hz (n = 21), which tend to be lower than that of normal rats (15.9 ± 1.8 Hz, n = 38) although there was no significant difference (P = 0.068). Local administration of 0.1 mM gabazine increased the spontaneous firing rate of pallidal neurons from 10.3 ± 2.5 Hz to 13.0 ± 2.6 Hz (n = 21, P < 0.001, Figures 3A,B). The average increase was 46.0 ± 8.8%, which was significantly different compared to vehicle injection (basal: 10.7 ± 2.5 Hz; saline: 11.0 ± 3.0 Hz; increase: 2.5 ± 2.6%, n = 14, P < 0.001, Figures 3A,B). More than 20% increase in firing rate was observed in 14 out of the 21 neurons receiving gabazine administration (basal: 8.0 ± 1.9 Hz; gabazine: 11.6 ± 2.4 Hz; increase: 65.9 ± 9.3%, n = 14). Similarly, a negative correlation between gabazine-induced excitation and the basal firing rate was observed in these 14 neurons (r = −0.70, P < 0.01, Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Effects of gabazine on the spontaneous firing of pallidal neurons on lesioned side of 6-OHDA parkinsonian rats. (A) Typical frequency histogram showing that gabazine increased the firing rate of a pallidal neuron by 84.0%. (B) Pooled data summarizing the effects of gabazine and normal saline on the firing rate of globus pallidus neurons on the lesioned side of 6-OHDA-lesioned rats. ***P < 0.001. (C) Correlation between the increase of firing rate and the basal firing level in pallidal neurons with more than 20% increase in firing rate.

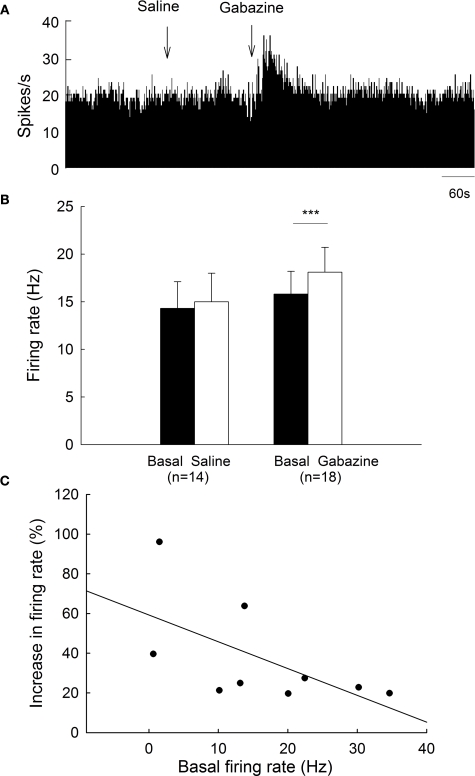

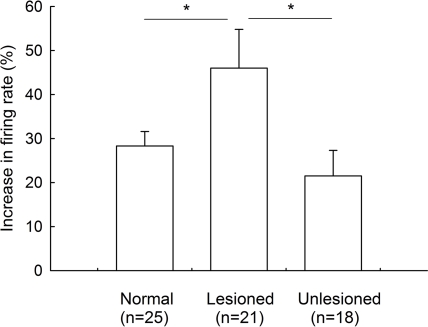

On the unlesioned side, pallidal neurons discharged with a mean firing rate of 15.8 ± 2.4 Hz (n = 18), which was not different from that of normal rats (15.9 ± 1.8 Hz, n = 38, P > 0.05). Micro-pressure ejection of 0.1 mM gabazine increased the frequency of spontaneous firing from 15.8 ± 2.4 Hz to 18.1 ± 2.6 Hz (n = 18, P < 0.001, Figures 4A,B). The average increase was 21.5 ± 5.8%, which was significantly different from that of vehicle injection (basal: 14.3 ± 2.8 Hz; saline: 15.0 ± 3.0 Hz; increase: 4.3 ± 3.9%, n = 14, Figures 4A,B). Nine of the eighteen neurons receiving gabazine administration displayed at least 20% increase in firing rate (basal: 13.0 ± 3.3 Hz; gabazine: 16.3 ± 3.9 Hz; increase: 37.3 ± 8.7%, n = 9). As shown in Figure 4C, gabazine induced a stronger excitation with slower basal firing rate on these nine pallidal neurons, although there was no significance (r = −0.60, P = 0.08). Figure 5 summarized the effects of gabazine on the firing rate of pallidal neurons between 6-OHDA-lesioned rats and normal rats. Gabazine-induced increase in firing rate on the lesioned side (46.0 ± 8.8%, n = 21) was stronger than that on unlesioned side 21.5 ± 5.8%, n = 18, P < 0.05), as well as that in normal rats (28.3 ± 3.3%, n = 25, P < 0.05). There was no significant difference between the unlesioned side of parkinsonian rats and normal rats (P > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effects of gabazine on the spontaneous firing of pallidal neurons on unlesioned side. (A) Frequency histogram illustrating that gabazine increased the firing rate of a pallidal neuron by 43.5%. (B) Pooled data summarizing the effects of gabazine and normal saline on the firing rate of globus pallidus neurons. ***P < 0.001. (C) Correlation between the increase of firing rate and the basal firing level in pallidal neurons with more than 20% increase in firing rate.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the increase in firing rate induced by intrapallidal microinjection of gabazine between 6-OHDA-lesioned rats and normal rats. *P < 0.05. Unlesioned refers to contralateral side in lesioned rats.

Behavioral effects of intrapallidal injections of gabazine on normal rats

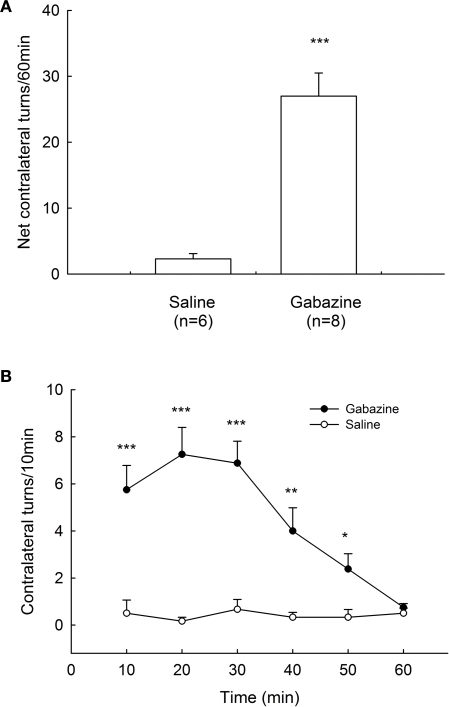

To elucidate the motor function of GABAA receptors in globus pallidus, we microinjected gabazine into the globus pallidus of awake rats unilaterally. In control group, normal saline injection caused a small net contralateral turning of 2.3 ± 0.8 turns/60 min (n = 6). In contrast, microinjection of gabazine (0.1 mM) into the globus pallidus produced robust contralateral rotations of the animals (27.0 ± 3.5 turns/60 min, n = 8, P < 0.001 compared with control). The rotations appeared almost immediately and invariably within 10 min after injection and typically peaked between 10–30 min. This turning behavior usually persisted for 1 h. These data are summarized in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Rotational behavior induced by intrapallidal microinjection of gabazine. (A) Unilateral microinjection of 0.1 mM gabazine into globus pallidus induced contralateral rotation in normal rats recorded in 60 min. (B) Time course of the contralateral rotation induced by intrapallidal microinjection of gabazine and saline. *** P < 0.001, ** P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 compared to saline.

Effects of gabazine on apomorphine-induced rotational behavior in 6-OHDA-lesioned rats

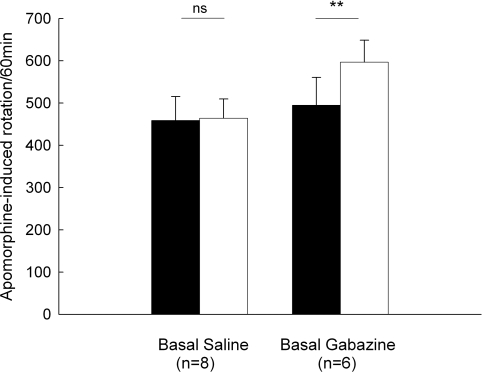

Animals given unilateral 6-OHDA lesions were tested for rotational behavior induced by an injection of apomorphine (0.2 mg/kg, s.c.). In the control group, apomorphine-induced baseline rotation was 458.5 ± 56.9 turns/60 min (n = 8). Intrapallidal microinjection of normal saline did not significantly alter the rotation (463.9 ± 45.7 turns/60 min, P > 0.05). While in another group (n = 6), intrapallidal microinjection of 0.1 mM gabazine produced a significant increase in rotational scores compared to baseline (baseline: 494.8 ± 65.8 turns/60 min, gabazine: 596.8 ± 51.7 turns/60 min, increase 25.5 ± 8.6%, P < 0.01). These data are summarized in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Effects of intrapallidal microinjection of gabazine on apomorphine-induced rotation in 6-OHDA-lesioned rats. Gabazine significantly enhanced apomorphine-induced contralateral rotation. **P < 0.01; ns: not significant.

Discussion

Previous studies have indicated that activation of GABAA receptors inhibited the neuronal activity of globus pallidus in rodents and primates (Kita, 1992; Querejeta et al., 2001; Cobb and Abercrombie, 2003; Galvan et al., 2005). However, it is not clear whether endogenous GABAA neurotransmission modulates the firing rate of pallidal neurons in rats. Our present results showed that microinjections of GABAA receptor antagonist, gabazine, evoked an increase in the firing rate of pallidal neurons, suggesting the tonic activity of GABAA receptors in globus pallidus. Consistently, previous electrophysiological studies indicated that local application of GABAA receptor antagonist increased the firing rate of globus pallidus neurons in awake monkeys (Matsumura et al., 1995; Kita et al., 2004). Additionally, the present electrophysiological studies revealed that gabazine exerted stronger excitatory effects in the globus pallidus of 6-OHDA-lesioned side, which suggests a high level of GABAergic activity on globus pallidus of lesioned side. This phenomenon may be mediated mainly by two possible reasons: (1) the expression of postsynaptic GABAA receptors is increased under parkinsonian state; (2) the release of GABA from striatopallidal and/or pallidopallidal terminals is increased on the lesioned side. Considering the previous morphological reports that the expression of GABAA receptors or their subunits was decreased in the globus pallidus on the side ipsilateral to unilateral 6-OHDA-lesioned rats (Yu et al., 2001; Nielsen and Soghomonian, 2004; Katz et al., 2005), it is supposed that enhanced GABA release may be the major reason for the stronger gabazine-induced excitation on lesioned side. There exists abundant evidence supporting this hypothesis. For example, by using microdialysis, the release of GABA was consistently increased in the globus pallidus of parkinsonian animals (Robertson et al., 1991). Consistently, an increase in GAD67 mRNA, the rate-limiting enzymes of GABA synthesis, has been reported in the globus pallidus of nigrostriatal lesioned rats (Soghomonian and Chesselet, 1992; Billings and Marshall, 2004) and MPTP-treated primates (Soares et al., 2004). Furthermore, gabazine-induced excitation on unlesioned side was similar to that in normal rats, which is in line with morphological study that no significant change in GABAA receptor expression was observed in the brain of contralateral sides in 6-OHDA treated rats (Araki et al., 2002). In addition to above mentioned two reasons, some other possibilities should also be considered. For example, increased GABA activity could be caused by less efficient GABA reuptake. Although there is no evidence that GABAA receptors are altered in 6-OHDA parkinsonian model, inhibition could be made more effective by changes in intraneuronal Cl− level. And of course, the lower frequency of ongoing firing in the 6-OHDA treated animals could reflect reduced excitatory input or a change in some peptide action.

In addition to GABAA receptors, morphological studies also revealed the expression of GABAB receptors in the globus pallidus (Bowery et al., 1987). The enhancement of GABA release may modulate the activity of globus pallidus by activating GABAB receptors. However, our previous electrophysiological studies indicated that blockade of GABAB receptors only induced a very weak increase in the spontaneous firing of pallidal neurons (Chen et al., 2008). The possible reason is that activation of GABAB receptors may exert two opposite effects on pallidal neurons. On one hand, activation of presynaptic GABAB receptors would excite pallidal neurons by reducing the release of GABA. On the other hand, activation of GABAB receptors would inhibit pallidal neurons by both presynaptic inhibition of glutamate release and postsynaptic hyperpolarization. Therefore, GABAB receptors only induced weaker tonic activity on the spontaneous firing of globus pallidus neurons. Another possible explanation is that GABAB receptors in globus pallidus are abundantly expressed early postnatally and decline to lower levels as the brain matures (Turgeon and Albin, 1994).

The present results also showed that gabazine-induced excitation was dependent on the basal activity of pallidal neurons in both normal and parkinsonian rats. Similarly, it was reported recently that the bicuculline-induced excitation was related to basal discharge rate in substantia nigra reticulata neurons. The neurons with slower basal firing rate were more affected by bicuculline (Windels and Kiyatkin, 2006). It was known that pallidal neurons display a tonic, high-frequency discharge that is interrupted by pauses (Filion and Tremblay, 1991; Magill et al., 2001). These pauses or reductions in the activity of pallidal neurons are likely to be evoked by a striatal or perhaps intrapallidal GABAergic inputs (Kita and Kitai, 1991; Cooper and Stanford, 2000; Chan et al., 2005). Therefore, we hypothesize that the pallidal neurons with slow-firing may receive more GABAergic inputs, while the fast-firing cells receive less GABAergic afferents. That is probably one of the reasons for the negative correlation between gabazine-induced excitation and basal firing rate in globus pallidus neurons. In addition, the firing rate of pallidal neurons also depends on the excitatory input mainly originating from subthalamic nucleus.

The globus pallidus in rats is believed to be the equivalent of the external pallidum, a component of the indirect pathway, in higher mammals. Rotational behavior employed in the past suggested that unilateral increase in the activity of globus pallidus neurons would result in contralateral turning, presumably due to an increased motor output from the ipsilateral motor cortex. For example, unilateral activation of the globus pallidus by picrotoxin produced contralateral rotational behavior in rats (Herrera-Marschitz and Ungerstedt, 1987), while inhibition of the neurons leads to ipsilateral turning (Aiko et al., 1988; Sañudo-Peña and Walker, 1998; Chen and Yung, 2003; Chen et al., 2004). Thus, the present finding that gabazine-induced contralateral turning in normal rats was caused via an excitation of pallidal neurons. Furthermore, the present behavioral studies demonstrated that intrapallidal microinjection of gabazine potentiated apomorphine-induced contralateral rotation in unilaterally 6-OHDA-lesioned rats. This contralateral response is attributed to the stimulation of supersensitive D1-receptor and D2-receptor activation, especially in the lesioned hemisphere (Betarbet et al., 2002; Schober, 2004). This model would predict an augmentation of apomorphine-induced rotational behavior following reduction of the ipsilateral striatopallidal pathway, as was observed in this study. Similarly, by using a different animal model, early study revealed that microinjection of GABAA receptor antagonist, bicuculline, into the globus pallidus had marked antiparkinsonian effects (Maneuf et al., 1994).

In summary, the present study indicated that gabazine increased the spontaneous firing rate of globus pallidus neurons and potentiated apomorphine-induced contralateral rotation in 6-OHDA-lesioned rats. Therefore, blockade of GABAA receptors in globus pallidus could counteract the excessive striatopallidal activity under parkinsonian state and represent a potential avenue for future pharmacotherapeutic development in Parkinson's disease.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants from the Ministry of Education of China (200810650002), the Bureau of Science and Technology of Qingdao (08-2-1-2-nsh) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (30670664, 30870800) to L. Chen.

Abbreviations

6-OHDA, 6-hydroxydopamine; GABA, γ-aminobutyric acid; MPTP, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine

References

- Aiko Y., Hosokawa S., Shima F., Kato M., Kitamura K. (1988). Alterations in local cerebral glucose utilization during electrical stimulation of the striatum and globus pallidus in rat. Brain Res. 442, 43–52 10.1016/0006-8993(88)91430-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki T., Matsubara M., Fujihara K., Kato H., Imai Y., Itoyama Y. (2002). Gamma-aminobutyric acidA and benzodiazepine receptor alterations in the rat brain after unilateral 6-hydroxydopamine lesions of the medial forebrain bundle. Neurol. Res. 24, 107–112 10.1179/016164102101199486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman H., Feingold A., Nini A., Raz A., Slovin H., Abeles M., Vaadia E. (1998). Physiological aspects of information processing in the basal ganglia of normal and parkinsonian primates. Trends Neurosci. 21, 32–38 10.1016/S0166-2236(97)01151-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betarbet R., Sherer T. B., Greenamyre J. T. (2002). Animal models of Parkinson's disease. Bioessays 24, 308–318 10.1002/bies.10067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billings L. M., Marshall J. F. (2004). Glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 mRNA regulation in two globus pallidus neuron populations by dopamine and the subthalamic nucleus. J. Neurosci. 24, 3094–3103 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5118-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolam J. P., Hanley J. J., Booth P. A. C., Bevan M. D. (2000). Synaptic organisation of the basal ganglia. J. Anat. 196, 527–542 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19640527.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolam J. P., Smith Y. (1992). The striatum and the globus pallidus send convergent synaptic inputs onto single cells in the entopeduncular nucleus of the rat: a double anterograde labelling study combined with postembedding immunocytochemistry for GABA. J. Comp. Neurol. 321, 456–476 10.1002/cne.903210312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowery N., Hudson A. L., Price G. W. (1987). GABAA and GABAB receptor site distribution in the rat central nervous system. Neuroscience 20, 365–383 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90098-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breit S., Bouali-Benazzouz R., Popa R. C., Gasser T., Benabid A. L., Benazzouz A. (2007). Effects of 6-hydroxydopamine-induced severe or partial lesion of the nigrostriatal pathway on the neuronal activity of pallido-subthalamic network in the rat. Exp. Neurol. 205, 36–47 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calon F., Goulet M., Blanchet P. J., Martel J. C., Piercey M. F., Bédard P. J., Di Paolo T. (1995). Levodopa or D2 agonist induced dyskinesia in MPTP monkeys: correlation with changes in dopamine and GABAA receptors in the striatopallidal complex. Brain Res. 680, 43–52 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00229-J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadha A., Dawson L. G., Jenner P. G., Duty S. (2000). Effect of unilateral 6-hydroxydopamine lesions of the nigrostriatal pathway on GABA(A) receptor subunit gene expression in the rodent basal ganglia and thalamus. Neuroscience 95, 119–126 10.1016/S0306-4522(99)00413-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan C. S., Surmeier D. J., Yung W. H. (2005). Striatal information signaling and integration in globus pallidus: timing matters. Neurosignals 14, 281–289 10.1159/000093043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Chan C. S, Yung W. H. (2004). Electrophysiological and behavioral effects of zolpidem in rat globus pallidus. Exp. Neurol. 186, 212–220 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Wang H. T., Han X. H., Li Y. L., Cui Q. L., Xie J. X. (2008). Behavioral and electrophysiological effects of pallidal GABAB receptor activation and blockade on haloperidol-induced akinesia in rats. Brain Res. 1244, 65–70 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.09.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Yung W. H. (2003). Effects of the GABA-uptake inhibitor tiagabine in rat globus pallidus. Exp. Brain Res. 152, 263–269 10.1007/s00221-003-1549-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb W. S., Abercrombie E. D. (2003). Relative involvement of globus pallidus and subthalamic nucleus in the regulation of somatodendritic dopamine release in substantia nigra is dopamine-dependent. Neuroscience 119, 777–786 10.1016/S0306-4522(03)00071-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A. J., Stanford I. M. (2000). Electrophysiological and morphological characteristics of three subtypes of rat globus pallidus neurone in vitro. J. Physiol. 527, 291–304 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00291.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Deredy W., Branston N. M., Samuel M., Schrag A., Rothwell J. C., Thomas D. G., Quinn N. P. (2000). Firing patterns of pallidal cells in parkinsonian patients correlate with their pre-pallidotomy clinical scores. Neuroreport 11, 3413–3418 10.1097/00001756-200010200-00029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filion M., Tremblay L. (1991). Abnormal spontaneous activity of globus pallidus neurons in monkeys with MPTP-induced parkinsonism. Brain Res. 547, 142–151 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan A., Villalba R. M., West S. M., Maidment N. T., Ackerson L. C., Smith Y., Wichmann T. (2005). GABAergic modulation of the activity of globus pallidus neurons in primates: in vivo analysis of the functions of GABA receptors and GABA transporters. J. Neurophysiol. 94, 990–1000 10.1152/jn.00068.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths P. D., Sambrook M. A., Perry R., Crossman A. R. (1990). Changes in benzodiazepine and acetylcholine receptors in the globus pallidus in Parkinson's disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 100, 131–136 10.1016/0022-510X(90)90023-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimer G., Bar-Gad I., Goldberg J. A., Bergman H. (2002). Dopamine replacement therapy reverses abnormal synchronization of pallidal neurons in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine primate model of parkinsonism. J. Neurosci. 22, 7850–7855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Marschitz M., Ungerstedt U. (1987). The dopamine-gamma aminobutyric acid interaction in the striatum of the rat is differently regulated by dopamine D-1 and D-2 types of receptor: evidence obtained with rotational behavioral experiments. Acta Physiol. Scand. 129, 371–380 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1987.tb08080.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz J., Nielsen K. M., Soghomonian J. J. (2005). Comparative effects of acute or chronic administration of levodopa to 6-hydroxydopaminelesioned rats on the expression of glutamic acid decarboxylase in the neostriatum and GABAA receptors subunits in the substantia nigra, pars reticulata. Neuroscience 132, 833–842 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.12.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelland M. D., Soltis R. P., Anderson L. A., Bergstrom D. A., Walters J. R. (1995). In vivo characterization of two cell types in the rat globus pallidus which have opposite responses to dopamine receptor stimulation: comparison of electrophysiological properties and responses to apomorphine, dizocilpine, and ketamine anesthesia. Synapse 20, 338–350 10.1002/syn.890200407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kincaid A. E., Albin R. L., Newman S. W., Penney J. B., Young A. B. (1992). 6-Hydroxydopamine lesions of the nigrostriatal pathway alter the expression of glutamate decarboxylase messenger RNA in rat globus pallidus projection neurons. Neuroscience 51, 705–718 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90309-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita H. (1992). Responses of globus pallidus neurons to cortical stimulation: intracellular study in the rat. Brain Res. 589, 84–90 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91164-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita H., Kita T. (2001). Number, origins, and chemical types of rat pallidostriatal projection neurons. J. Comp. Neurol. 437, 438–448 10.1002/cne.1294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita H., Kitai S. T. (1991). Intracellular study of rat globus pallidus neurons: membrane properties and responses to neostriatal, subthalamic and nigral stimulation. Brain Res. 564, 296–305 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91466-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita H., Nambu A., Kaneda K., Tachibana Y., Takada M. (2004). Role of ionotropic glutamatergic and GABAergic inputs on the firing activity of neurons in the external pallidum in awake monkeys. J. Neurophysiol. 92, 3069–3084 10.1152/jn.00346.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita H., Tokuno H., Nambu A. (1999). Monkey globus pallidus external segment neurons projecting to the neostriatum. Neuroreport 10, 1467–1472 10.1097/00001756-199905140-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald R. L., Olsen R. W. (1994). GABAA receptor channels. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 17, 569–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill P. J., Bolam J. P., Bevan M. D. (2001). Dopamine regulates the impact of the cerebral cortex on the subthalamic nucleus-globus pallidus network. Neuroscience 106, 313–330 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00281-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnin M., Morel A., Jeanmonod D. (2000). Single-unit analysis of the pallidum, thalamus and subthalamic nucleus in parkinsonian patients. Neuroscience 96, 549–564 10.1016/S0306-4522(99)00583-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maneuf Y. P., Mitchell I. J., Crossman A. R., Brotchie J. M. (1994). On the role of enkephalin cotransmission in the GABAergic striatal efferents to the globus pallidus. Exp. Neurol. 125, 65–71 10.1006/exnr.1994.1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura M., Tremblay L., Richard H., Filion M. (1995). Activity of pallidal neurons in the monkey during dyskinesia induced by injection of bicuculline in the external pallidum. Neuroscience 65, 59–70 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00484-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mink J. W. (1996). The basal ganglia: focused selection and inhibition of competing motor programs. Prog. Neurobiol. 50, 381–425 10.1016/S0301-0082(96)00042-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Z., Bouali-Benazzouz R., Gao D., Benabid A. L., Benazzouz A. (2000). Changes in the firing pattern of globus pallidus neurons after the degeneration of nigrostriatal pathway are mediated by the subthalamic nucleus in the rat. Eur. J. Neurosci. 12, 4338–4344 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen K. M., Soghomonian J. J. (2004). Normalization of glutamate decarboxylase gene expression in the entopeduncular nucleus of rats with a unilateral 6-hydroxydopamine lesion correlates with increased GABAergic input following intermittent but not continuous levodopa. Neuroscience 123, 31–42 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochi M., Koga K., Kurokawa M., Kase H., Nakamura J., Kuwana Y. (2000). Systemic administration of adenosine A(2A) receptor antagonist reverses increased GABA release in the globus pallidus of unilateral 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats: a microdialysis study. Neuroscience 100, 53–62 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00250-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel W. H., Nitsch C., Mugnaini E. (1984). Immunocytochemical demonstration of the GABA-ergic neurons in rat globus pallidus and nucleus entopeduncularis and their GABA-ergic innervation. Adv. Neurol. 40, 91–98 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H. S., Penney J. B., Young A. B. (1985). Gamma-aminobutyric acid and benzodiazepine receptor changes induced by unilateral 6- hydroxydopamine lesions of the medial forebrain bundle. J. Neurochem. 45, 1396–1404 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb07205.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent A., Hazrati L. N. (1995). Functional anatomy of the basal ganglia. II. The place of subthalamic nucleus and external pallidum in basal ganglia circuitry. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 20, 128–154 10.1016/0165-0173(94)00008-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent A., Sato F., Wu Y., Gauthier J., Levesque M., Parent M. (2000). Organization of the basal ganglia: the importance of axonal collateralization. Trends Neurosci. 23, S20–S27 10.1016/S1471-1931(00)00022-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G., Watson C. (1986). The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- Peng Z., Hauer B., Mihalek R. M., Homanics G. E., Sieghart W., Olsen R. W., Houser C. R. (2002). GABA(A) receptor changes in delta subunit-deficient mice: altered expression of alpha4 and gamma2 subunits in the forebrain. J. Comp. Neurol. 446, 179–197 10.1002/cne.10210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querejeta E., Delgado A., Valdiosera R., Erlij D., Aceves J. (2001). Intrapallidal D2 dopamine receptors control globus pallidus neuron activity in the rat. Neurosci. Lett. 300, 79–82 10.1016/S0304-3940(01)01550-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querejeta E., Oviedo-Chavez A., Araujo-Alvarez J. M., Quinones-Cardenas A. R., Delgado A. (2005). In vivo effects of local activation and blockade of 5-HT1B receptors on globus pallidus neuronal spiking. Brain Res. 1043, 186–194 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.02.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz A., Vaadia E., Bergman H. (2000). Firing patterns and correlations of spontaneous discharge of pallidal neurons in the normal and the tremulous 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine vervet model of parkinsonism. J. Neurosci. 20, 8559–8571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson R. G., Clarke C. A., Boyce S., Sambrook M. A., Crossman A. R. (1990). The role of striatopallidal neurones utilizing gamma-aminobutyric acid in the pathophysiology of MPTP-induced parkinsonism in the primate: evidence from [3H]flunitrazepam autoradiography. Brain Res. 531, 95–104 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90762-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson R. G., Graham W. C., Sambrook M. A., Crossman A. R. (1991). Further investigations into the pathophysiology of MPTP-induced parkinsonism in the primate: an intracerebral microdialysis study of gamma-aminobutyric acid in the lateral segment of the globus pallidus. Brain Res. 563, 278–280 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91545-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruskin D. N., Rawji S. S., Walters J. R. (1998). Effects of full D1 dopamine receptor agonists on firing rates in the globus pallidus and substantia nigra pars compacta in vivo: tests for D1 receptor selectivity and comparisons to the partial agonist SKF 38393. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 286, 272–281 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sañudo-Peña M. C., Walker J. M. (1998). Effect of intrapallidal cannabinoids on rotational behavior in rats: interactions with the dopaminergic system. Synapse 28, 27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schober A. (2004). Classic toxin-induced animal models of Parkinson's disease: 6-OHDA and MPTP. Cell Tissue Res. 318, 215–224 10.1007/s00441-004-0938-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder J. A., Schneider J. S. (2001). Alterations in expression of messenger RNAs encoding two isoforms of glutamic acid decarboxylase in the globus pallidus and entopeduncular nucleus in animals symptomatic for and recovered from experimental Parkinsonism. Brain Res. 888, 180–183 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)03097-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder J. A., Schneider J. S. (2002). ABA-opioid interactions in the globus pallidus: [D-Ala2]-Met-enkephalinamide attenuates potassium-evoked GABA release after nigrostriatal lesion. J. Neurochem. 82, 666–673 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01010.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shink E., Smith Y. (1995). Differential synaptic innervation of neurons in the internal and external segments of the globus pallidus by the GABA- and glutamate-containing terminals in the squirrel monkey. J. Comp. Neurol. 358, 119–141 10.1002/cne.903580108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieghart W. (1995). Structure and pharmacology of gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptor subtypes. Pharmacology 47, 181–234 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Y., Bevan M. D., Shink E., Bolam J. P. (1998). Microcircuitry of the direct and indirect pathways of the basal ganglia. Neuroscience 86, 353–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares J., Kliem M. A., Betarbet R., Greenamyre J. T., Yamamoto B., Wichmann T. (2004). Role of external pallidal segment in primate parkinsonism: comparison of the effects of 1-Methyl-4-Phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced parkinsonism and lesions of the external pallidal segment. J. Neurosci. 24, 6417–6426 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0836-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soghomonian J. J., Chesselet M. F. (1992). Effects of nigrostriatal lesions on the levels of messenger RNAs encoding two isoforms of glutamate decarboxylase in the globus pallidus and entopeduncular nucleus of the rat. Synapse 11, 124–133 10.1002/syn.890110205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soghomonian J. J., Pedneault S., Audet G., Parent A. (1994). Increased glutamate decarboxylase mRNA levels in the striatum and pallidum of MPTP-treated primates. J. Neurosci. 14, 6256–6265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr P. A., Rau G. M., Davis V., Marks W. J., Ostrem J. L., Simmons D., Lindsey N., Turner R. S. (2005). Spontaneous pallidal neuronal activity in human dystonia: comparison with Parkinson's disease and normal macaque. J. Neurophysiol. 93, 3165–3176 10.1152/jn.00971.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turgeon S. M., Albin R. L. (1994). Postnatal ontogeny of GABAB binding in rat brain. Neuroscience 62, 601–613 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90392-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann T., Soares J. (2006). Neuronal firing before and after burst discharges in the monkey basal ganglia is predictably patterned in the normal state and altered in parkinsonism. J. Neurophysiol. 95, 2120–2133 10.1152/jn.01013.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windels F., Kiyatkin E. A. (2006). GABAergic mechanisms in regulating the activity state of substantia nigra pars reticulata neurons. Neuroscience 140, 1289–1299 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.03.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisden W., Laurie D. J., Monyer H., Seeburg P. H. (1992). The distribution of 13 GABAA receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat brain. I. Telencephalon, diencephalon, mesencephalon. J. Neurosci. 12, 1040–1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T. S., Wang S. D., Liu J. C., Yin H. S. (2001). Changes in the gene expression of GABA(A) receptor alpha1 and alpha2 subunits and metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 in the basal ganglia of the rats with unilateral 6-hydroxydopamine lesion and embryonic mesencephalic grafts. Exp. Neurol. 168, 231–241 10.1006/exnr.2000.7590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. H., Sato M., Tohyama M. (1991). Different postnatal development profiles of neurons containing distinct GABAA receptor beta subunit mRNAs in the rat forebrain. J. Comp. Neurol. 308, 586–613 10.1002/cne.903080407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]