Abstract

The Federal government has promoted National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) to reduce mental health disparities among Hispanic and Native American populations. In 2005, the State of New Mexico embarked upon a comprehensive reform of its behavioral health system with an emphasis on improving cultural competency. Using survey methods, we examine which language access services (i.e., capacity for bilingual care, interpretation, and translated written materials) and organizational supports (i.e., training, self-assessments of cultural competency, and collection of cultural data) mental health agencies in New Mexico had at the onset of a public sector mental health reform (Office of Minority Health, 2001).

Keywords: Cultural competency, mental health, agency capacity, rural

Introduction

A number of published studies document racial and ethnic disparities in mental health access and use in the United States (Alegría et al., 2002; Cook, McGuire, & Miranda, 2007; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001; Wells, Klap, Koike, & Sherbourne, 2001). The Federal government has promoted National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) to help eliminate health care disparities due to inequities based on language, ethnicity, and race (Office of Minority Health, 2001). Culturally competent care is defined as a set of behaviors, attitudes and policies that enable effective work with individuals from different cultures (Cross, Bazron, Dennis, & Issacs, 1989; Office of Minority Health, 2001). Few published studies examine whether mental health agencies receiving public funds have language access services (i.e., capacity for bi-lingual care, interpretation, and translated written materials) and organizational supports (i.e., training, self-assessments of cultural competency, and collection of cultural data in behavioral health records), the basic building blocks identified in the CLAS standards.

In this paper, we present the number of agencies serving adults with serious mental illness in New Mexico that have language access services and organizational supports to ensure provision of culturally competent care. We examine whether the availability of language access services and organizational supports at an agency is influenced by the linguistic characteristics of its patient catchment area, referred to here as the mental health service area. We hypothesize that the higher percentage of the population in the mental health service area that speaks Spanish or Native American languages, the more likely the agency is to have these services and supports.

The findings in this paper document the extent to which language access services and organizational supports are in place in New Mexico, a largely rural state that has launched a comprehensive reform of its publicly-funded mental health system. A long-term goal of this reform is to promote the delivery of culturally competent services. Future analyses will document the extent to which this goal is achieved.

Ethnic and linguistic disparities in mental health service use

Research on Native American mental health access and use is limited because the population is small, geographically dispersed, and heterogeneous (Beals, Manson, Mitchell, & Spicer, 2003; Beals, Manson et al., 2005; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). Compared to whites, Native Americans are less likely to seek and receive mental health services, to visit mental health specialists, and to be prescribed psychotropic medications (Beals, Manson et al., 2005; Libby et al., 2007). A much higher percentage of Native Americans than whites use traditional healing services, an indication of the importance of non-Western forms of treatment within this population (Beals, Novins et al., 2005; Walls, Johnson, Whitbeck, & Hoyt, 2006).

A number of studies have examined differences between Hispanics, as a cultural group, and white populations. Hispanic populations receive less appropriate mental health treatment when compared to white populations (Cabassa, Zayas, & Hansen, 2006; Wells et al., 2001). For example, Hispanics are less likely to receive psychiatric medication (Han & Liu, 2005; Lasser, Himmelstein, Woolhandler, McCormick, & Bor, 2002), use outpatient services (Lasser et al., 2002; Ojeda & McGuire, 2006), and visit mental health specialists (Alegría et al., 2002; Kimerling & Baumrind, 2005; Vega, Kolody, & Aguilar-Gaxiola, 2001). Disparities for Hispanic people often persist after adjusting for service need and financial factors that decrease mental health care access, such as income and health insurance status (Alegría et al., 2002; Barrio et al., 2003; Chow, Jaffee, & Snowden, 2003; Kimerling & Baumrind, 2005).

In addition, speaking non-English languages exacerbate existing service use disparities for ethnic minority populations. Hispanics with limited English proficiency (LEP) are less likely to use mental health services than those fluent in English (Barrio et al., 2003; Fiscella, Franks, Doescher, & Saver, 2002).

Calls for improved cultural competency to reduce disparities

The adoption of strategies to enhance linguistic and cultural competency within health agencies may improve access, service use, and quality of care for ethnic minority populations (Lieu et al., 2004; Opler, Ramirez, Dominguez, Fox, & Johnson, 2004) and individuals with LEP (Miranda et al., 2003; Sue, Fujino, Hu, Takeuchi, & Zane, 1991; Ziguras, Klimidis, Lewis, & Stuart, 2003). Reports released by the Surgeon General (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1999), the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health (2003), and the American College of Mental Health Administration (Dougherty, 2004) call for the elimination of racial, ethnic and linguistic disparities in access, quality of care, and disability burden through culturally competent service provision. More recently, the National Association for State Mental Health Program Directors (2004) released an action paper that urges mental health commissioners to personally lead cultural competency improvement initiatives in their states.

Federal agencies have developed definitions, standards, and guidelines for ensuring that publicly-funded agencies deliver culturally competent medical care including mental health care (Center for Mental Health Services, 2000; Office of Minority Health, 2001). These guidelines identify widely accepted language access services and organizational supports for cultural competency to improve access and quality of care for ethnic minorities and individuals with LEP (Office of Minority Health, 2001). Federal civil rights law requires that agencies provide linguistically appropriate care, and this mandate is reiterated in the CLAS standards ("Lau v. Nichols," 1974).

A critical gap in the published literature is the lack of statewide surveys reporting how many agencies have in place language services and cultural competency organizational supports that are recommended in the CLAS standards. A small number of published survey studies report availability of language services, organizational supports and other cultural competency practices in agencies delivering primary care (Vandervort & Melkus, 2003) and substance abuse treatment (Campbell & Alexander, 2002; Howard, 2003). We were unable to find any peer-reviewed studies reporting similar findings of statewide surveys pertinent to mental health agencies. However, San Diego County and the State of Hawaii each spearheaded organizational self-assessments of publicly-funded mental health agencies and documented the results in technical reports for internal planning (Hawaii Adult Mental Health Division, 2005; Refowitz, 2002).

Study context

Because of its large Hispanic and Native American populations, New Mexico is an ideal state in which to study language access services and organizational supports available in mental health agencies. New Mexico is one of three states and the District of Columbia in which ethnic minorities comprise the numerical majority. Forty-two percent of the state’s overall population of 1.8 million is Hispanic or Latino of any race, 9.5% is Native American, and 1.9% is African American (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000a, 2000e). More than one-third of New Mexicans age 5 and older speak a language other than English at home, the second highest percentage in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2003). Spanish is the most common non-English language spoken at home. Navajo is the most common Native American language spoken at home. Members of the 22 pueblos and tribes that have land bases within the state commonly speak Native American languages (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000f) . Many of these languages have only an oral form. Therefore mental health agencies in New Mexico have to consider whether written materials are appropriate for the specific Native American language groups in their areas.

In addition, New Mexico is a predominately rural state with an average of 15 persons per square mile compared with 80 persons per square mile for the United States as a whole (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000g). The low population density combined with the relatively small state population results in small numbers of mental health organizations and insufficient capacity (Gale & Deprez, 2003; Gamm, Stone, & Pittman, 2003; Hauenstein et al., 2007).

Studying New Mexico is also particularly relevant because the state embarked upon a comprehensive transformation of its publicly-funded mental health system, placing a high priority on improving cultural competency (Hyde, 2004; Interagency Behavioral Health Purchasing Collaborative, 2006). The goal of the reform is to eliminate the fragmentation of mental health services that 15 separate state departments and offices had historically managed, provided, or funded. Under the reform, the state government initiated the creation of a single set of services, standards, access procedures, utilization protocols, and performance measures for all mental health agencies accepting public funds.

Cultural competency is an important value and principal of this reform (Interagency Behavioral Health Purchasing Collaborative, 2005, 2006, 2008). ValueOptions New Mexico (VONM) is the single managed care company responsible for the day-to-day operations of the state’s publicly-funded behavioral health system. The company employs staff whose responsibility is to work on cultural competency issues, including an Agency Liaison for Cultural Diversity Issues and several liaisons to the state’s Native American communities. During the first year of the reform, a goal of VONM’s cultural competency plan was to develop and implement policies for direct service providers that comply with the CLAS standards. In addition, VONM aimed to increase access to culturally competent services through the identification of mental health agencies that specialize in culturally relevant “best practices” (Interagency Behavioral Health Purchasing Collaborative, 2005, 2006, 2008). However, the priorities of the state government and VONM centered on the establishment of new systems for enrollment, billing, utilization review, quality management, and oversight rather than the introduction of new cultural competency interactions during the first year of the reform. VONM’s or the current managed behavioral partner’s purchasing power and influence on mental health agencies will likely increase as it is entrusted to oversee the delivery of greater numbers of state-funded services.

Research Questions

In this paper, we answer two primary research questions pertaining to mental health agencies that serve adults with serious mental illness in New Mexico. First, how many mental health agencies have language access services (i.e., capacity for bilingual care, interpretation, and translated written materials) and organizational supports (i.e., training, self-assessments of cultural competency, and collection of cultural data in behavioral health records)? This question is answered by surveying the agencies about the availability of specific language access services and organizational supports promoted in the CLAS standards. Second, we ask whether mental health agencies located in service areas with higher percentages of Spanish or Native American language speakers are more likely to have language access services and organizational supports. We hypothesize that the higher percentage of people in the mental health service area that speak Spanish or Native American languages, the more likely the agency is to have these services and supports.

Methods

This baseline survey is one component of a five-year, multi-method assessment that also uses ethnographic methods and secondary analysis of state data to evaluate how the reform affects mental health access and quality of care for adults with serious mental illness. The assessment has a special emphasis on the impact of the reform on Hispanic and Native American populations living in rural areas.

Sample

To construct our statewide sampling frame of agencies, we reviewed VONM’s complete list of agencies in its behavioral health network. This list, compiled from five separate state agencies and departments that were previously responsible for funding services, identified 306 agencies that deliver mental health and substance use treatment. Our research team created a final list of agencies that met three principal criteria: 1) serving adults with serious mental illness, i.e., schizophrenia, major depression and bi-polar disorder; 2) accepting Medicaid or Department of Health indigent patients; and 3) comprising either a group practice or an agency. The exclusion of independent practitioners reflected the overall study’s purpose of examining the impact of the reform on agencies that serve adults with serious mental illness; therefore the study focused on understanding factors that affected organizations.

For the first level of review, we cross-checked the information contained in the VONM list of agencies with existing sources, such as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) website of available mental health services (U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2005) and a previous statewide provider survey conducted in New Mexico (Technical Assistance Collaborative, 2002). We removed agencies that only offered services to children and adolescents and those that were located outside of New Mexico. We also removed duplicate listings. Theses listings resulted from the practice of state agencies and departments using slightly different designations to refer to the same agency.

In the second level of review, we contacted the remaining agencies to verify that they met all the study criteria. Finally, state officials, faculty from the Department of Psychiatry at the University of New Mexico, and a representative from a professional association of organizations serving adults with serious mental illness reviewed the revised agency list to confirm its accuracy. The final list of 74 agencies that met all the criteria included inpatient facilities, community mental health centers, Federally Qualified Health Centers, and outpatient providers. The most common reasons for exclusion are as follows: no services for adults with serious mental illness (103, 42%); children-only services (50, 20%); independent practitioners (29, 12%); and based in state other than New Mexico (23, 9%).

Survey Development and Administration

The cultural competency data reported in this study were collected as part of a 55-item telephone survey designed to assess the general status of mental health provider agencies at the start of the New Mexico reform. In addition to cultural competency, we asked about available mental health services, staffing patterns, administrative issues, finances, clinical care, and perceptions of behavioral health reform. The survey results reported in this paper measured the availability of language access services and organizational supports pertinent to cultural competency within the VONM provider network during the first year of the reform (July 1, 2005 to June 30, 2006), which was prior to the implementation of major cultural competency improvement efforts. The State of New Mexico designed the first year of the reform as a period of “do no harm” that emphasized the introduction of new, billing enrollment and reporting systems by VONM, rather than the introduction of clinical practice innovations, including those that focused on enhancing cultural competency within agencies (Willging et al., 2007). We are conducting a follow-up survey to assess the reform’s impact in its third year (July 1, 2007 to June 30, 2008), after clinical practice innovations have been introduced.

Survey questions were developed based on systematic reviews of the 2005 VONM contract (Interagency Behavioral Health Purchasing Collaborative, 2005), provider surveys designed to study mental health reforms in Massachusetts and Michigan (Beinecke, Shepard, Leung, & Sousa, 2002; Beinecke & Vore, 2002; Beinecke & Woliver, 2000; Hodgkin, Shepard, & Beinecke, 2002; Shepard, Daley, Ritter, Hodgkin, & Beinecke, 2002), as well as input from several national experts in the field. The survey included questions about services and supports that are promoted in the CLAS standards (numbers 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 10). Based on three required CLAS language standards, the survey included questions about whether the agency employed non-English speaking staff and interpreters and had written translations of patient materials and notices informing individuals with LEP of their right to language assistance services. Other CLAS standards recommend that agencies conduct regular organizational self-assessments, offer ongoing education and training for staff at all levels (e.g., administrative, clinical, and executive) and include cultural data in behavioral health records regarding patient race, ethnicity, spoken language, and written language.

The cultural competency questions consisted primarily of structured queries offering close-ended Yes/No responses about whether agencies employed staff speaking non-English languages and engaged in specific organizational support activities. A small number of open-ended questions solicited descriptions of designated services and the number of cultural competency training hours that agencies required of staff. Translated materials were defined as printed patient materials available in non-English languages (Goode, 2002). Organizational self-assessment was defined as an inventory of an agency’s policies, practices, and procedures related to the provision of culturally and linguistically appropriate services in health care (Office of Minority Health, 2001). To minimize respondent burden, the questions did not explore the availability (e.g., number of staff or hours) or quality of the cultural competency services. Refer to the Appendix for the complete list of questions.

Mental health agencies were contacted to participate in the survey between August 2006 and January 2007. Trained staff administered the survey over the telephone to senior agency leaders, usually the chief executive officer or the clinical director. The survey required an average of 45 minutes to complete. Staff entered survey responses into an electronic Accesstm database. Sixty-six agencies participated in the survey resulting in a response rate of 89%. The majority of non-participating agencies were for-profit entities that expressed concern about sharing proprietary information that was not publicly available. More than half of the participating agencies were private non-profits (54%). The next most common classifications were private for-profits (21%) and Federally-operated agencies such as the Veterans Administration and the Indian Health Service (13%). Forty-two percent of mental health agencies responding to the survey received 50% or more of revenue from VONM, which underscores the state’s purchasing power under the reform. Forty-one percent of all respondent agencies were licensed by the New Mexico Department of Health to operate as community mental health centers.

Definition of Mental Health Service Areas in New Mexico

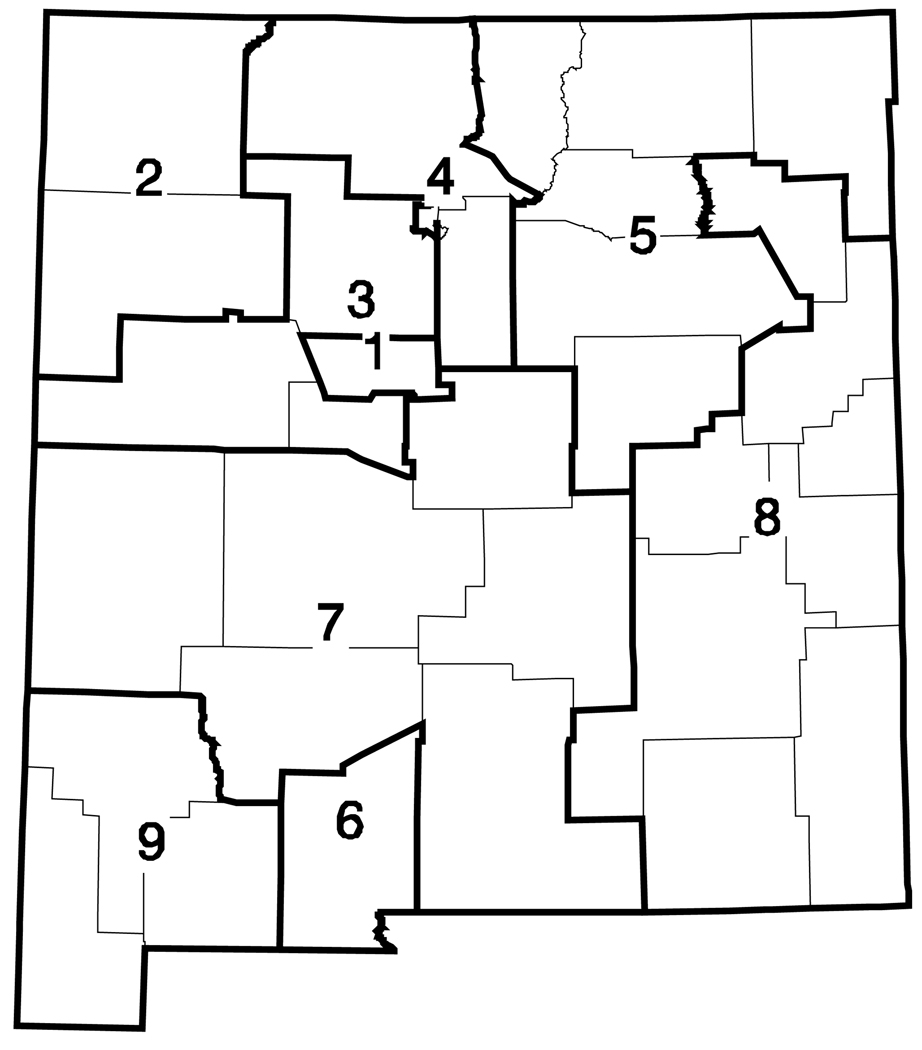

We divided New Mexico into 9 mental health service areas using as the starting point the 15 local collaborative “districts” developed by the state government to administer the reform. “Local collaboratives” served as coordinating and planning groups to identify community needs, help develop a range of resources, and ensure the responsiveness and relevance of behavioral health services within the area (The MacArthur Foundation Network on Mental Health Policy Research, 2005). Because the number of survey respondents was small in some local collaborative areas, we reduced the number of mental health services areas for our analysis from 15 to 9 by merging districts that appeared to be part of the same natural catchment area. Figure 1 presents the geographic location of the mental health service areas.

Figure 1.

Mental health service areas in New Mexico

We used U.S. Census data to determine the following demographics of the 9 mental health service areas: 1) percentage of the total population that live in rural areas, because the U.S. Census does not present rural population by age; 2) percentage of adults (older than 18 years of age) that speak Spanish or Native American languages at home; and 3) percentage of adults that self-identify as Hispanic or Native American (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000b, 2000c) .

Analyses

The results from the survey were analyzed in two ways. First, we assessed the number of mental health agencies that had language access services and organizational supports identified as essential in the CLAS standards. For language access services and organizational supports specifically related to Spanish or Native American languages, we examined whether the prevalence of a particular practice or support was related to the language context of the surrounding service area. For Spanish language services, agencies were divided into two groups depending on whether their service areas had less than or greater than the statewide service area median (28.7%) percentage Spanish speakers. For Native American services we divided agencies into those located in the northwest and northwest central areas that had the highest percentage of Native Americans compared to the remainder of the state. Chi-square tests (and Fisher’s exact test where needed) were utilized to assess for statistically significant differences in the prevalence of the respective language services and supports between areas classified as either high or low prevalence for the particular language.

In the second set of analyses we constructed multivariate models for multiple indicators related to the availability of cultural competency practices. These indicators were summarized in two types of measures: 1) the presence/absence of a specific cultural competency service or support offered by the agency; and 2) hours of cultural competency training required of agency staff. We then assessed the relationship of these indicators to organizational characteristics and the cultural characteristics of each agency’s service area. Binary outcomes were modeled using logistic regression. Continuous outcomes (i.e., hours of training) were first transformed to square root scales to create a more normal distribution and then modeled using linear regression. Each model contained a measure of the percentage of Spanish speakers and/or Native American language speakers In addition we included the percentage of the service area’s population in rural areas as an independent variable in the models, because rural agencies tend to be smaller, with fewer resources available to fund cultural competency initiatives (Calloway, Fried, Johnsen, & Morrissey, 1999; Hauenstein et al., 2007; Rost, Fortney, Fischer, & Smith, 2002). We also examined the impact of an agency’s for-profit or non-profit status, including private nonprofit and governmental agencies, and its potential relationship to the availability of culturally competent services. This organizational distinction was included to account for the greater likelihood of nonprofit agencies to offer more comprehensive services, more innovative treatment and less profitable services (Harrison & Sexton, 2004; Schlesinger, Dorwart, Hoover, & Epstein, 1997; Schlesinger & Gray, 2006).

Agencies were clustered within operationally defined mental health service areas, introducing possible correlation among agencies in the services offered (Fitzmaurice, Laird, & Ware, 2004). Multilevel modeling techniques were utilized to account for the nesting of agency observations within the larger geographical mental health services areas and the potential for the agencies within service areas to have unmeasured commonalities with each other. Specifically, the logistical and linear regression analyses were conducted using the Generalized Linear Latent And Mixed Models (GLLAMM) framework available in the Stata 10.1 statistical software program (Rabe-Hesketh & Skrondal, 2005). For the regression analyses, random intercept models were generated in which the intercept for each region varied to reflect unmeasured service area differences. In additional analyses, available upon request, results from logistical and linear regression models not accounting for the nesting of organizations within service areas were almost the same as the multilevel random intercept model results. However, we reported the results from the multilevel models as these models provide a conservative approach to handling the hierarchical nature of our data.

To examine whether consistent modeling results were obtained, we generated models using the adaptive quadrature approach for maximum likelihood estimation with different numbers of numerical integration points (Rabe-Hesketh & Skrondal, 2005). The findings across models were essentially identical indicating that the approximation techniques were arriving at a stable result.

Given the exploratory nature of the study and the relatively small sample size, we consider findings significant at the level of p = < 0.10 level. Regression coefficients, standard errors, p-values for the test of no effect, and 90% confidence intervals are presented. Odds ratios and 90% intervals of the odds ratios are also shown for the logistic regression model results. No adjustments were made for conducting multiple statistical tests.

In addition to the results presented below, we also developed separate models with the percentage of the population in the mental health service areas self-identifying as Hispanic or Native American. Race/ethnicity models resulted in similar statistically significant explanations of the availability of written materials and spoken communication services. However, we only report models developed for language spoken at home in this article, because these variables more directly measure mental health service areas’ need for language assistance. These findings indicate that the availability of non-linguistic cultural competency supports is related to the percentage of the mental health service area population that speaks either Spanish or Native American languages because of the overlap of ethnic and LEP populations in New Mexico.

Findings

As shown in Table 1, the mental health service areas differed in terms of demographic characteristics. New Mexico is a predominately rural state and only the Albuquerque mental health service area had less than 20% of the population living in rural areas. The percentage of responding agencies that were non-profits and public agencies ranged from 0 to 40%. Adults speaking Spanish at home represented between 24.1% and 52.3% of the population in 8 of the 9 service areas. However, adults speaking Native American languages at home were concentrated in two mental health service areas in the northwest (38.8% and 9.9%). Racial and ethnic demographics exhibited similar geographic patterns as language spoken at home. Individuals self-identifying as Hispanic represented between 29.0% and 61.4% of the population in 8 of the 9 service areas. Persons self-identifying as Native American were concentrated in the same two mental health services areas (13.1% and 47.7%) as individuals speaking Native American languages.

Table 1.

Demographics of mental health (MH) service areas

| MH service area number & name |

MH orgs surveyed |

2000 Census population |

Rural (%) |

For- profit /public agencies (%) |

Adults speak Spanish at home (%) |

Adults speak NAL at home (%) |

Adult Hispanic (%) |

Adult Native American (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Albuquerque | 23 | 556678 | 4.4 | 26.1 | 25.8 | 1.8 | 38.3 | 3.8 |

| 2. Northwest | 7 | 188599 | 48.9 | 0.0 | 8.5 | 38.8 | 13.1 | 47.7 |

| 3. Northwest Central | 7 | 181655 | 27.0 | 28.6 | 25.3 | 9.9 | 36.4 | 13.3 |

| 4. North Central | 7 | 188825 | 30.4 | 14.3 | 38.2 | 2.0 | 47.2 | 4.3 |

| 5. Northeast | 3 | 88328 | 55.4 | 33.3 | 52.3 | 1.9 | 61.4 | 2.9 |

| 6. South Central | 5 | 174682 | 20.4 | 40.0 | 51.6 | 0.3 | 57.9 | 1.1 |

| 7. Southeast Central | 6 | 133511 | 46.3 | 33.3 | 24.1 | 1.9 | 29.0 | 4.2 |

| 8. Southeast Plains | 6 | 244818 | 24.4 | 0.0 | 28.8 | 0.1 | 33.4 | 1.2 |

| 9. Southwest | 2 | 61950 | 42.5 | 0.0 | 42.5 | 0.1 | 47.2 | 1.2 |

NAL Native American Languages

Availability of language access services and organizational supports

The survey findings report the number of mental health agencies in New Mexico that have adopted language access services and organizational supports to improve cultural competency, described in six of the Federal government’s CLAS standards, during the first year of the New Mexico reform. In general, agencies were more likely to adopt language access services to reduce language barriers in mental health delivery than organizational supports that address nonlinguistic cultural barriers. This section presents the most noteworthy findings. More detailed information on the prevalence of services and supports can be found in Table 2–Table 5.

Table 2.

Spoken Spanish communication services

| Less than median Spanish- speaking in MH service area a N = 43 Yes |

Greater than median Spanish- speaking in MH service area a N = 23 Yes |

P-value chi-square test |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Direct-service clinical staff who speak Spanish |

29 | 69 | 18 | 83 | 0.23 |

| Administrative support staff who speak Spanish |

27 | 64 | 19 | 86 | 0.06 |

| Trained Spanish interpreters |

16 | 37 | 7 | 30 | 0.58 |

| MH service areas 1, 4–9 N = 50 Yes |

MH service areas 2–3 N = 14 Yes |

P-value chi-square test |

|||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Direct-service clinical staff who speak NAL |

13 | 26 | 7 | 50 | 0.09 |

| Administrative Support staff who speak NAL |

13 | 26 | 9 | 64 | 0.01 |

| Trained NAL interpreters | 10 | 20 | 4 | 29 | 0.49 |

The median percent of Spanish speakers at home in MH service areas is 28.7%.

NAL Native American Languages

Table 5.

Other cultural competency (cc) practices

| Yes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | ||

| Organizational self-assessment of cultural competency | |||

| Conduct organizational self-assessment N = 65 | 25 | 38.5 | |

| Cultural information in behavioral health records | |||

| Include race and ethnicity N = 65 | 62 | 95.4 | |

| Include language N = 65 | 57 | 87.7 | |

| Include spoken language N = 64 | 46 | 71.9 | |

| Include tribal affiliation N = 63 | 44 | 69.8 | |

| Include written language N = 60 | 24 | 40.0 | |

| Training N = 66 | |||

| Require direct-service staff receive training on cc | 48 | 72.7 | |

| Require administrative support staff receive training on cca | 31 | 48.4 | |

| N = 63 | Average Hours | ||

| Average hours of training for direct-service staff annuallya | 3.4 | ||

| Average hours of training for direct-service staff in first year | 1.3 | ||

| Average hours of training for support staff annually | 1.8 | ||

| Average hours of training for support staff in first year | 0.8 | ||

N = 64

Spoken communication services

Due to the variation in Spanish spoken at home within the catchment areas, we present the spoken language communication above and below the mean of the population speaking Spanish at home (28.7%). As shown in Table 2, a high percentage of agencies employed Spanish-speaking interpreters and clinical and administrative staff in areas above the mean; however the difference was only statistically significant for administrative support staff (p = 0.06). A higher percentage of agencies employed Native American language services in the northwest and northwest central mental health service areas and the difference was statistically significant for administrative and direct-service clinical staff (p = 0.01, p = 0.09).

Translation of written materials

Overall, eighty-one percent of agencies translated one or more consumer education materials into non-English languages. Data are not shown. The results presented in Table 3 indicate that more agencies translated materials into Spanish (73%) than into Native American languages (12%). As with the spoken communication services, we presented the rates of agencies offering translated written materials based on the percentage of the population speaking Spanish and Native American languages. The higher percentage of organizations in areas with more Spanish speakers was statistically significant (p = 0.08). Likewise, the higher percentage of organizations in the north and northwest central areas offering translated materials was also statistically significant (p = 0.07).

Table 3.

Materials translated into Spanish and Native American Languages

|

Less than median Spanish-speaking in MH service areaa N = 43 Yes |

Greater than median Spanish-speaking in MH service area a N = 23 Yes |

P-value chi-square test |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Materials translated into Spanish |

29 | 67 | 20 | 87 | 0.08 |

|

MH service areas 1, 4–9 N= 52 Yes |

MH service areas 2–3 N = 14 Yes |

2-sided Fisher’s exact test |

|||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Materials translated into NAL |

4 | 8 | 4 | 29 | 0.06 |

The median percent of Spanish speakers at home in MH service areas is 28.7%.

NAL Native American Languages

The survey also collected information on the translation of specific materials into Spanish. Data are not shown. Agencies in areas with a higher percentage of Spanish speakers at home had higher percentages of the majority of specific materials translated into Spanish, except for notification of the availability of language assistance, and these differences were statistically significant. Due to the small number of agencies translating specific materials into Native American languages, we did not analyze the responses.

Designated clinical services

As presented in Table 4, agencies were more likely to offer designated clinical services for Native Americans (38.4%) than for Hispanics (13.6%). The higher percentages of agencies in areas with larger Native-American language speakers were statistically significant for designated services for Native Americans (p = < 0.01). The greater availability of these services for Native Americans may be the result of Indian Health Service programs that target this population. Examples of designated services for Native Americans included sweat lodges, talking circles, diagnostic ceremonies and clinical services delivered in Native American languages. Designated services for Hispanics were largely clinical services delivered in Spanish.

Table 4.

Designated services

|

Less than median Spanish-speaking in MH service areasa N = 43 Yes |

Greater than median Spanish-speaking in MH service areasa N = 23 Yes |

P-value chi-square test |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Designated services for Hispanics |

4 | 9.3% | 5 | 21.7 | 0.16 |

|

MH service areas 1, 4–9 N= 52 Yes Yes |

MH service areas 2–3 N = 14 Yes Yes |

P-value chi-square test |

|||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Designated services for Native Americans |

11 | 21.6% | 9 | 64.3% | 0.00 |

Median Spanish speaking percentage is 28.7

Organizational self-assessment of cultural competency

Table 5 presents the distribution of additional cultural competency measures within our sample organizations. Thirty-nine percent of agencies conducted their own organizational self-assessment in the first year of the reform.

Inclusion of cultural information in behavioral health records

Race and language were the most common types of cultural information included in behavioral health records (95.4% and 87.8% respectively). Less than three-quarters of agencies included tribal affiliation in records (69.8%) or more specific information about an individual’s spoken language (71.9%). Written language was included in records of 40% of agencies.

Cultural competency training

Table 5 presents additional information on the cultural competency training requirements. More agencies required that direct-service clinical staff receive ongoing education and training (72.7%) as compared to training and education for administrative support staff (48.4%). On average, agencies required that direct-service clinical staff complete 3.4 hours annually and that support staff complete 1.8 hours. Fewer hours of training were required in the first year of employment (1.3 direct-service clinical staff; 0.8 administrative staff).

Multivariate Modeling of Cultural Competency Practices

Spoken language services

The results of the multilevel, multivariate logistic regression models are presented in Table 6. The following analyses evaluated whether the probability that an agency employed bilingual staff was influenced by service area and organizational characteristics. In terms of Spanish language services, having a larger rural population was associated with a reduced likelihood of providing Spanish-speaking clinical staff. For each 1% increase in the percentage of the rural population (p = 0.02), the odds that an agency offered services with Spanish-speaking clinical staff declined by 4%. The population speaking Spanish at home approached a statistically significant, positive relationship with the probability of providing Spanish-speaking administrative staff (p = 0.07). For-profit status increased the probability that an agency offered Spanish interpreters (p = 0.09).

Table 6.

Statistical models of cultural competency (CC) practices

| Variable | Log odds ratio |

Standard error log OR |

P-value | Odds ratio |

90% LCL odds ratio |

90% UCL odds ratio |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative support staff who speak Spanish |

% Spanish speakers at home |

0.05 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 1.05 | 1.00 | 1.11 |

| % Rural | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.01 | |

| For-profit vs. non-profit | −0.37 | 0.71 | 0.61 | 0.69 | 0.17 | 2.78 | |

| Direct service clinical staff who speak Spanish |

% Spanish speakers at home |

0.03 | 0.03 | 0.23 | 1.03 | 0.98 | 1.09 |

| % Rural | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.99 | |

| For-profit vs. non-profit | 0.67 | 0.86 | 0.44 | 1.96 | 0.36 | 10.68 | |

| Trained Spanish interpreters |

% Spanish speakers at home |

0.02 | 0.03 | 0.54 | 1.02 | 0.97 | 1.07 |

| % Rural | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.98 | 0.95 | 1.01 | |

| For-profit vs. non-profit | 1.09 | 0.63 | 0.09 | 2.98 | 0.86 | 10.34 | |

| Administrative support staff who speak NAL |

% NAL speakers at home |

0.07 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 1.07 | 1.00 | 1.15 |

| % Rural | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.49 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.05 | |

| For-profit vs. non-profit | −0.48 | 0.74 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.15 | 2.62 | |

| Direct service clinical staff who speak NAL |

% NAL speakers at home |

0.06 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 1.12 |

| % Rural | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.74 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.03 | |

| For-profit vs. non-profit | −0.38 | 0.73 | 0.61 | 0.68 | 0.16 | 2.89 | |

| Trained NAL interpreters |

% NAL speakers at home |

0.03 | 0.03 | 0.28 | 1.03 | 0.98 | 1.09 |

| % Rural | −0.00 | 0.02 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 1.04 | |

| For-profit vs. non-profit | −0.48 | 0.85 | 0.57 | 0.62 | 0.12 | 3.27 | |

| Any written materials in Spanish |

% Spanish speakers at home |

1.03 | 0.03 | 0.31 | 1.03 | 0.98 | 1.08 |

| % Rural | −0.00 | 0.02 | 0.84 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.03 | |

| For-profit vs. non-profit | 0.19 | 0.74 | 0.80 | 1.21 | 0.28 | 5.11 | |

| Any written materials in NALa |

% NAL speakers at home |

0.04 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 1.04 | 0.98 | 1.11 |

| % Rural | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 1.06 | |

| For-profit vs. non-profit | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Race/ethnicity data in recordb |

% Spanish speakers at home |

-- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| % NAL speakers at home |

-- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| % Rural | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| For-profit vs. non-profit | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Tribe in record | % Spanish speakers at home |

0.06 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 1.06 | 0.97 | 1.15 |

| % NAL speakers at home |

0.04 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 1.04 | 0.95 | 1.14 | |

| % Rural | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.61 | 1.01 | 0.97 | 1.05 | |

| For profit vs. non-profit | −0.29 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.74 | 0.20 | 2.79 | |

| Language in record |

% Spanish speakers at home |

0.16 | 0.14 | 0.25 | 1.17 | 0.90 | 1.53 |

| % NAL speakers at home |

0.04 | 0.08 | 0.59 | 1.04 | 0.89 | 1.22 | |

| % Rural | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.72 | 1.01 | 0.95 | 1.07 | |

| For profit vs. non-profit | −1.86 | 0.89 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.89 | |

| Spoken language in record |

% Spanish speakers at home |

−0.00 | 0.04 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 1.08 |

| % NAL speakers at home |

−0.02 | 0.05 | 0.62 | 0.98 | 0.89 | 1.07 | |

| % Rural | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.54 | 1.01 | 0.97 | 1.06 | |

| For profit vs. non-profit | −0.08 | 0.69 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.24 | 3.55 | |

| Written language in record |

% Spanish speakers at home |

0.02 | 0.04 | 0.56 | 1.02 | 0.95 | 1.10 |

| % NAL speakers at home |

0.04 | 0.04 | 0.38 | 1.04 | 0.95 | 1.13 | |

| % Rural | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.59 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 1.03 | |

| For profit vs. non-profit | 0.57 | 0.63 | 0.37 | 1.76 | 0.51 | 6.04 | |

| Designated services for Hispanics |

% Spanish speakers at home |

0.12 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 1.12 | 1.02 | 1.23 |

| % Rural | −0.06 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 1.01 | |

| For-profit vs. non-profit | −0.44 | 0.98 | 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.09 | 4.41 | |

| Designated services for Native Americans |

% NAL speakers at home |

0.07 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 1.07 | 1.00 | 1.15 |

| % Rural | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.37 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.06 | |

| For-profit vs. non-profit | −1.74 | 1.10 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 1.50 | |

| Cultural competency self-assessment |

% Spanish speakers at home |

0.03 | 0.03 | 0.40 | 1.03 | 0.96 | 1.10 |

| % NAL speakers at home |

0.01 | 0.04 | 0.77 | 1.01 | 0.94 | 1.09 | |

| % Rural | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.26 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.06 | |

| For-profit vs. non-profit | 0.29 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 1.33 | 0.38 | 4.73 | |

NAL Native American Languages

Model unable to converge with for-profit indicator included due to minimal variation in the dependent variable across for-profit indicator categories. Results presented generated by a model that did not include the for-profit indicator variable.

Model unable to converge due to minimal variation in dependent variable.

The models developed for Native American spoken languages produced similar results on the impact of the percentage of population speaking these languages at home, but there were no statistically significant results for the percentage in rural areas. The odds of having Native American language-speaking administrative support staff increased by an estimated 7% with each 1% increase in the percentage of the population speaking Native American languages at home (p = 0.04). Likewise, the odds that an agency offered services from clinical staff who speak a Native American language increased by an estimated 6% for each 1% increase in the percentage of the population speaking Native American languages at home (p = 0.05).

Written materials

There were no significant associations between the independent variables and whether an agency offered any written materials in either a Native American language or in Spanish.

Cultural information in behavioral health records

For-profit status reduced the odds that an agency included the language spoken by an individual by 186% (p = 0.04).

Designated clinical services

The percentage of the population that speaks Spanish at home increased the likelihood that an agency offered designated services for Hispanics by an estimated 12% for each 1% increase in the percentage of the population speaking Spanish at home (p = 0.01). There was also a statistically significant estimated increase of 7% in the odds that an agency offered designated services for Native Americans for each 1% increase in the percentage of the population speaking Native American languages at home (p = 0.05). Rurality was not statistically significant, but approached a negative relationship with designated services for Hispanics (p = 0.07). Non-profit/public status had no statistically significant impact on whether an agency offered designated services.

Other cultural competency organizational supports

There were no statistically significant findings for any of the models developed to explain whether agencies conducted organizational self-assessments of cultural competency.

We also developed multivariate regression models for the number of training hours of the cultural competency training. There were few significant findings. Data are not shown.

Discussion

The overall survey results suggest that mental health agencies in New Mexico had developed some capacity to serve Hispanic and Native American populations at the start of the state’s behavioral health reform. However, this capacity varied among agencies. Almost three-quarters of the mental health agencies employed bilingual staff, translated written materials, and required clinical staff to complete cultural competency training. Only one-third of mental health agencies conducted annual organizational self-assessments of cultural competency and translated documents into the patients’ written language about their right to language assistance.

Statistical models indicate that mental health agencies are responding to the language needs of their service areas. More specifically, the likelihood that agencies offered Spanish-speaking administrative staff, spoken communication in Spanish, Native American language-speaking clinical and administrative staff, and spoken communication in Native American languages increased with the percentage of the population speaking the respective languages at home. In addition, mental health agencies appeared to be responsive to service area needs in terms of offering translations of written materials, requiring more hours for clinical staff in cultural competency, and developing targeted services for Hispanics and Native Americans.

The models indicate different effects of rurality for Spanish and Native American languages. We found significant negative impacts of rurality on the availability of language services and organizational supports for the percentage of the population speaking Spanish at home, but no significant impacts for Native Americans languages.

The survey findings suggest that the great majority of mental health agencies in New Mexico need translated materials that describe critical aspects of mental health care, such as what services are available and how to submit a grievance or complaint, in order to meet basic cultural competency standards. The higher percentage of agencies that offer Spanish language supports is likely to increase as the percentage of the New Mexican population that speaks Spanish continues to rise as a result of Mexican immigration (U.S. Census Bureau, 2003, 2006). The lower percentage of agencies translating written materials into Native American languages is in part explained by the concentration of Native Americans in the northwestern part of the state. In addition, many Native American languages have only an oral form. For others, a written form is a recent development.

A potential role for the state government and its managed care partner is to provide leadership and resources (e.g., financial, staff and other) for an initiative to translate commonly used materials that can be distributed to all mental health agencies. A number of states and managed care plans have successful initiatives to implement strategies for translating and distributing materials on health care issues. For example, the State of New York translates consent forms, patient rights information and program descriptions for use in state-operated programs (C. Cave, personal communication, October 10, 2007). Molina Healthcare, a Medicaid-focused health plan operating in California, translates into six languages patient risk assessments, member rights and responsibilities, and information explaining the process for accessing interpreters (M. Ryan, personal communication, October 11, 2007).

Our survey also found that nearly two-thirds of mental health agencies had not conducted an annual organizational self-assessment, a critical first step in undertaking initiatives to improve cultural competency (Siegel, Haugland, & Chambers, 2003). Self-assessments have the potential to educate clinicians, administrative support staff, and executive leadership about cultural competency capacity and to gain their support for the implementation of an action plan (Goode, Jones, & Mason, 2002). Therefore, an agency’s involvement in a self-assessment can counter employees’ overestimation of their ability to provide culturally competent services and propensity to minimize the importance of nonlinguistic cultural factors (Quintero, Lilliott, & Willging, 2007).

VONM’s cultural competency plan includes the goal of encouraging mental health agencies to conduct organizational self-assessments of cultural competency. To increase the number of agencies undertaking such assessments, VONM or the state’s managed behavioral health partner could offer training and supportive materials on how to do self-assessments to agencies across the state. An additional strategy would be for the state’s managed behavior health partner to include as a contractual requirement that mental health agencies complete annual organizational self-assessments.

New Mexico and other states with large limited-English speaking and ethnic populations that are seeking to increase the cultural competency of mental health agencies will face several challenges as they move forward with plans to improve this capacity. First, New Mexico and other states will need to combine agency survey information on cultural competency with data on mental health service use, pharmaceutical prescriptions, and individual background data collected during enrollment in order to perform statistical analyses to determine whether agencies that adopted more cultural competency services and supports offered better access to mental health care and improved outcomes for ethnic and linguistic minorities. The National Association for State Mental Health Program Directors (2004) affirms this approach in an action paper urging mental health commissioners to evaluate disparities in mental health access and service use between cultural groups in their states.

Second, states will need to develop complete assessments of how well mental health agencies are delivering culturally competent services. Cultural competency occurs during the patient/provider interaction and requires that direct service providers are knowledgeable about the influence of cultural, economic, and social factors (Quintero, Lilliot & Willging, 2007) and also spend adequate time to learn about how individuals understand their mental health issues, as well as their particular preferences and goals for mental health treatment (Kleinman & Benson, 2006; Vega et al., 2007). Surveys of staffing, policies and other structural characteristics of mental health agencies, such as the one reported here, cannot assess what occurs during actual mental health visits. States will need to employ qualitative research methods to more fully assess the quality of culturally competent services.

Third, state policy makers and program officials face difficulties in fostering the adoption of strategies to improve cultural competency because of the limited research on the effectiveness of current cultural competency guidelines, standards, and models (Anderson, Scrimshaw, Fullilove, Fielding, & Normand, 2003; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1999). States lack knowledge of which approaches are the most effective for disseminating and promoting cultural competency and how to prioritize specific approaches in order to maximize limited resources. The completion of additional evaluation research is essential to the promotion of cultural competency at a time when states are increasingly directing mental health funding to services with a strong evidence-base (Magnabosco, 2006; Rapp et al., 2005; Torrey et al., 2001). SAMHSA’s funding of work by the New York State Office of Mental Health has the potential to develop a limited number of performance measures for assessing cultural competency of mental health agencies (Siegel et al., 2000; Siegel et al., 2003).

Fourth, a challenge for New Mexico and other states is to advance multifaceted and specialized approaches that respond to the heterogeneity within Hispanic and Native American populations. For example, 42.1% of Hispanics in New Mexico self-identify as Mexican; 32.2% as Hispanic, 9.7% as Spanish, less than 1% as Cuban or Puerto Rican; and 13.2% as other Hispanic (U.S. Census Bureau, 2001). The majority are native-born Hispanics descended from individuals living in former Mexican territories that became part of the United States after the Mexican War of 1846–1848 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). In addition, 6% (114,858) of New Mexicans that identify as Hispanic are first-generation (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000d). Likewise, Native Americans belong to the 22 pueblos and tribes that have land bases within the state, as well as to numerous tribes located outside New Mexico (Technical Assistance Collaborative, 2002). Acculturation has been found to influence the symptomatology of mental illness and treatment preferences (Burnam, Hough, Karno, Escobar, & Telles, 1987; Lopez & Guarnaccia, 2000; Reichman, 2003). Cultural competency initiatives need to be extremely sensitive and flexible in order to respond to the full range of cultural influences and identities.

Limitations

This study has the challenge of conducting statistical analyses with small sample sizes, similar to other studies on mental health in rural areas (Hauenstein et al., 2007; Willging, Waitzkin, & Nicdao, 2008). To minimize the adverse impact of small sample size, we developed a survey that was brief enough for agency staff to complete in less than an hour and expended resources to assure a near universal response rate.

Despite our high response rate, the small sample size and the clustered nature of the data likely limit our capacity to identify small or potentially even moderate effects as statistically significant. As an exploratory study and first survey of cultural competency practices in New Mexico, we attempted to reduce the likelihood of overlooking potentially “true” relationships by considering p = < 0.1 to be an acceptable level of significance. However, additional research will be needed to confirm and expand upon our findings.

The results of this statewide survey apply only to mental health agencies that deliver services to adults with serious mental illness within New Mexico. Therefore, it is not representative of cultural competency practices among independent practitioners and primary care providers who deliver a limited set of mental health services (typically medication management and individual therapy) to the less severely mentally ill.

This survey depends on the accuracy of the self-report data collected from senior agency staff. Some respondents might have exaggerated the extent of language services and organizational supports to improve the profile of their agency. However since the survey does not ask about compliance with CLAS standards, but only capacity to deliver certain services and materials, we believe that this narrower approach minimizes risk of such bias. Furthermore, recall bias is less of a threat because of the small size of agencies in New Mexico that participated in the survey as indicated by a median size of 18 staff.

In order to keep the administration time reasonable and enhance the feasibility of the telephone survey, we did not collect qualitative information on the quality of services and supports such as the fluency of bi-lingual staff, the process for translating written materials, or the curriculum for the cultural competency training. We also did not collect information on the education, training, and experience of individual clinical staff in delivering culturally competent services. One indication of the gap between linguistic service need and mental health system capacity is the finding from a 2006 statewide mail survey funded by the State of New Mexico (Research and Polling Inc., 2006). This survey found that more than twice as many behavioral health agencies and independent practitioners were dissatisfied than satisfied with the availability of interpreters for individuals with language needs, 23% versus 10%. Qualitative research conducted prior to the reform confirms that lack of interpretation services is a problem in mental health agencies, particularly among those located in rural areas of New Mexico (Willging et al., 2008)

The survey questions reflect the Federal government’s emphasis on language accommodations in health services, which is due to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act and its prohibition on discrimination based on national origin, and does not include other types of cultural competent practices necessary to provide quality services in mental health care. The impact of culture in mental health care extends beyond language, race, and ethnicity to include consideration of religious or spiritual beliefs and practices and social difference based on age, gender, and sexuality, in addition to place of residence (The President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003).

Conclusion

The President’s New Freedom Commission (2003) asserted, “In a transformed mental health system, all Americans will share equally in the best available services and outcomes, regardless of race, gender, ethnicity, or geographic location.” New Mexico joins several other states (California, Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, and New York) that have begun to integrate cultural competency into their public mental health systems (National Technical Assistance Center for State Mental Health Planning & National Association State Mental Health Program Directors, 2004). Our statewide agency survey is one component of the information that the state government and its managed behavioral health partner can draw from to perform a comprehensive assessment of culturally competent mental health care for adults with chronic and persistent mental illness. Other data include mental health service claims data, pharmaceutical prescriptions, consumer assessments of service, and provider attitude surveys.

This study found that mental health agencies in New Mexico are more likely to implement language access services that address spoken and written language needs than cultural competency supports that address nonlinguistic aspects of culture. Our findings point to several areas for improvement in New Mexico, especially in terms of enhancing availability of translated materials, conducting organizational self-assessments of cultural competency, and offering designated services for ethnic minorities. As the only published statewide survey of language access services and organizational supports that promote cultural competency within mental health agencies, our research expands the knowledge base concerning the language services and cultural competency supports that mental health agencies have adopted. With its large Hispanic, Native American and limited English-speaking populations, New Mexico has a substantial need for culturally competent mental health services. This study has national relevance because the state’s ambitious initiative to maximize its influence and synchronize policies and practices for all publicly-funded mental health services may serve as a model for other states considering initiatives to enhance the seamlessness of mental health delivery systems and their capacity to deliver culturally competent care (The MacArthur Foundation Network on Mental Health Policy Research, 2005).

Acknowledgment

This study was primarily funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH0760840) and the Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration. However, the views expressed in this paper are those of the authors alone.

Appendix

Cultural Competency Questions from Safety-Net Institution Survey

1. In the first year of the reform (July 1, 2005 to June 30, 2006), did behavioral health

records include consumer self-report data on the following?

Race and Ethnicity □ Yes □ No

Tribe □ Yes □ No

Language □ Yes □ No

Spoken language □ Yes □ No

Written language □ Yes □ No

2. In the first year of the reform (July 1, 2005 to June 30, 2006), did this agency offer the

following culturally competent services:

a. Direct-service clinical staff who speak Spanish □ Yes □ No

b. Administrative support staff who speak Spanish □ Yes □ No

c. Direct-service clinical staff who speak

American Indian language(s) □ Yes □ No

d. Administrative support staff who speak

American Indian language(s) □ Yes □ No

e. Trained Spanish interpreters □ Yes □ No

f. Trained American Indian interpreters □ Yes □ No

g. Promotoras or tribal health representatives □ Yes □ No

h. Designated services for Hispanics □ Yes □ No

List:_________________________________________________________________________

i. Designated Services for American Indians □ Yes □ No

List:_________________________________________________________________________

3. In the first year of the reform (July 1, 2005 to June 30, 2006), did this agency require

that direct-service staff receive training in culturally competent behavioral health

services? Require means that direct-service staff cannot work at the agency unless they

complete the training.

□ Yes Go to Q. 3.a

□ No Go to Q. 4

a. If yes, please indicate the frequency and hours of training required. (Please

check all that apply.)

□ Within the first year of employment _______ hours

□ Less than annually _______ hours

□ Annually _______ hours

4. In the first year of the reform (July 1, 2005 to June 30, 2006), did this agency require

that administrative support staff receive training in culturally and linguistically

appropriate behavioral health services? Require means that administrative support staff

cannot work at the agency unless they complete the training.

□ Yes Go to Q. 4.a

□ No Go to Q. 5

a. If yes, please indicate the frequency and hours of training required.

□ Within the first year of employment _______ hours

□ Less than annual _______ hours

□ Annually _______ hours

5. In the first year of the reform (July 1, 2005 to June 30, 2006), which of the following

types of written materials were available in any non-English languages to your adult

consumers?

a. Consumer consent forms □ Yes □ No

b. Consumer education materials □ Yes □ No

c. Consumer satisfaction questionnaires/survey □ Yes □ No

d. Grievance/complaint procedures and forms □ Yes □ No

e. HIPAA notice □ Yes □ No

f. In-take forms □ Yes □ No

g. Materials describing services

available to consumers □ Yes □ No

h. Materials on how to access and use services □ Yes □ No

i. Notification of language assistance □ Yes □ No

j. Please specify in which languages written materials were available:

______________________________________________________________________________

6. In the first year of the reform (July 1, 2005 to June 30, 2006), did this agency conduct a

self-assessment of culturally competent-related activities? A self-assessment is an

inventory of an agency’s policies, practices, and procedures related to the

provision of culturally and linguistically appropriate services in health care. It

focuses on the capacities, strengths and weaknesses of the agency in providing

such services (USDHHS, National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically

Appropriate Services in Health Care, 2001).

□ Yes

□ No

Footnotes

Presented at: The Nineteenth National Institute of Mental Health Conference on Mental Health Services, Washington, DC, July 2007

References

- Alegría M, Canino G, Rios R, Vera M, Calderon J, Rusch D, Ortega AN. Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(12):1547–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LM, Scrimshaw SC, Fullilove MT, Fielding JE, Normand J. Culturally competent healthcare systems: A systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(3 Suppl):68–79. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrio C, Yamada AM, Hough RL, Hawthorne W, Garcia P, Jeste DV. Ethnic disparities in use of public mental health case management services among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(9):1264–1270. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.9.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Manson SM, Mitchell CM, Spicer P. Cultural specificity and comparison in psychiatric epidemiology: Walking the tightrope in American Indian research. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 2003;27(3):259–289. doi: 10.1023/a:1025347130953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Manson SM, Whitesell NR, Spicer P, Novins DK, Mitchell CM. Prevalence of DSM-IV disorders and attendant help-seeking in 2 American Indian reservation populations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(1):99–108. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Novins DK, Whitesell NR, Spicer P, Mitchell CM, Manson SM. Prevalence of mental disorders and utilization of mental health services in two American Indian reservation populations: Mental health disparities in a national context. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(9):1723–1732. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beinecke RH, Shepard DS, Leung M, Sousa D. Evaluation of the Massachusetts behavioral health program: Year 8. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2002;30(2):141–157. doi: 10.1023/a:1022585102102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beinecke RH, Vore N. Provider assessments of the Massachusetts behavioral health program: Year 7. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2002;29(6):519–524. doi: 10.1023/a:1020780411239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beinecke RH, Woliver R. Assessment of the Massachusetts behavioral health program: Year 6. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2000;28(2):107–129. doi: 10.1023/a:1026655423320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnam MA, Hough RL, Karno M, Escobar JI, Telles CA. Acculturation and lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders among Mexican Americans in Los Angeles. J Health Soc Behav. 1987;28(1):89–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa LJ, Zayas LH, Hansen MC. Latino adults' access to mental health care: A review of epidemiological studies. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006;33(3):316–330. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0040-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calloway M, Fried B, Johnsen M, Morrissey J. Characterization of rural mental health service systems. J Rural Health. 1999;15(3):296–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1999.tb00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell CI, Alexander JA. Culturally competent treatment practices and ancillary service use in outpatient substance abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22(3):109–119. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00221-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Mental Health Services. Cultural competence standards in managed mental health care for four underserved/underrepresented racial/ethnic groups. Rockville, MD: United States Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. pp. 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Chow JC, Jaffee K, Snowden L. Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services in poverty areas. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(5):792–797. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BL, McGuire T, Miranda J. Measuring trends in mental health care disparities, 2000 2004. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(12):1533–1540. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross TL, Bazron BJ, Dennis KW, Issacs MR. Towards a culturally competent system of care: A monograph on effective services for minority children who are severely emotionally disturbed. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Child Development Center; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty RH. Reducing disparity in behavioral health services: A report from the American College of Mental Health Administration. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2004;31(3):253–263. doi: 10.1023/b:apih.0000018833.22506.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Franks P, Doescher MP, Saver BG. Disparities in health care by race, ethnicity, and language among the insured: Findings from a national sample. Med Care. 2002;40(1):52–59. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Inter-Science; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gale JA, Deprez RD. A public health approach to the challenges of rural mental health services integration. In: Stamm BH, editor. Rural behavioral health care: An interdisciplinary guide. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gamm LD, Stone S, Pittman S. Mental health and mental disorders-- A rural challenge . [Retrieved October 18, 2008];Rural healthy people 2010. 2003 from http://www.srph.tamhsc.edu/centers/rhp2010/08Volume1mentalhealth.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Goode T. [Retrieved March 10, 2009];Promoting cultural diversity and cultural competency-- Self assessment checklist for personnel providing services and supports to children with disabilities & special health care needs. 2002 from http://www11.georgetown.edu/research/gucchd/NCCC/foundations/frameworks.html. [Google Scholar]

- Goode T, Jones W, Mason J. A guide to planning and implementing cultural competence organizational assessment. Washington, DC: National Center for Cultural Competence; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Han E, Liu GG. Racial disparities in prescription drug use for mental illness among population in US. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2005;8(3):131–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison JP, Sexton C. The paradox of the not-for-profit hospital. Health Care Manag (Frederick) 2004;23(3):192–204. doi: 10.1097/00126450-200407000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauenstein EJ, Petterson S, Rovnyak V, Merwin E, Heise B, Wagner D. Rurality and mental health treatment. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007;34(3):255–267. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawaii Adult Mental Health Division. [Retrieved October 2, 2007];3- year multicultural strategic plan [Electronic Version] 2005 from http://amh.health.state.hi.us/Public/REP/Planning/MulticulturalStrategicPlan.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin D, Shepard DS, Beinecke RH. Management of alcohol and drug abuse treatment by medical plans: Michigan providers' experience. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2002;20(1):79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Howard DL. Culturally competent treatment of African American clients among a national sample of outpatient substance abuse treatment units. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;24(2):89–102. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00348-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde PS. State mental health policy: A unique approach to designing a comprehensive behavioral health system in New Mexico. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(9):983–985. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interagency Behavioral Health Purchasing Collaborative. Statewide behavioral health services contract. Santa Fe, NM: State of New Mexico; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Interagency Behavioral Health Purchasing Collaborative. Statewide behavioral health services contract. Santa Fe, NM: State of New Mexico; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Interagency Behavioral Health Purchasing Collaborative. Statewide behavioral health services contract. Santa Fe, NM: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kimerling R, Baumrind N. Access to specialty mental health services among women in California. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(6):729–734. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.6.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A, Benson P. Culture, moral experience and medicine. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73(6):834–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser KE, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler SJ, McCormick D, Bor DH. Do minorities in the United States receive fewer mental health services than whites? Int J Health Serv. 2002;32(3):567–578. doi: 10.2190/UEXW-RARL-U46V-FU4P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau v. Nichols, 563 (Supreme Court 1974)

- Libby AM, Orton HD, Barth RP, Webb MB, Burns BJ, Wood PA, Spicer P. Mental health and substance abuse services to parents of children involved with child welfare: A study of racial and ethnic differences for American Indian parents. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007;34(2):150–159. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieu TA, Finkelstein JA, Lozano P, Capra AM, Chi FW, Jensvold N, Quesenberry CP, Farber HJ. Cultural competence policies and other predictors of asthma care quality for Medicaid-insured children. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):e102–e110. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.e102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez SR, Guarnaccia PJ. Cultural psychopathology: Uncovering the social world of mental illness. Annu Rev Psychol. 2000;51:571–598. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnabosco JL. Innovations in mental health services implementation: A report on state-level data from the U.S. evidence-based practices project. Implement Sci. 2006;1:13. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Duan N, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Lagomasino I, Jackson-Triche M, Wells KB. Improving care for minorities: Can quality improvement interventions improve care and outcomes for depressed minorities? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(2):613–630. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Technical Assistance Center for State Mental Health Planning, & National Association State Mental Health Program Directors. Cultural competency: Measurement as a strategy for moving knowledge into practice in state mental health systems. Alexandria, VA: National Technical Assistance Center for State Mental Health Planning & The National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors; 2004. pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Minority Health. [Retrieved March 10, 2009];National standards on culturally and linguistically appropriate services (CLAS): Final report. 2001 from http://www.omhrc.gov/assets/pdf/checked/finalreport.pdf.

- Ojeda VD, McGuire TG. Gender and racial/ethnic differences in use of outpatient mental health and substance use services by depressed adults. Psychiatr Q. 2006;77(3):211–222. doi: 10.1007/s11126-006-9008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opler LA, Ramirez PM, Dominguez LM, Fox MS, Johnson PB. Rethinking medication prescribing practices in an inner-city Hispanic mental health clinic. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10(2):134–140. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintero G, Lilliott E, Willging C. Substance abuse treatment provider views of "culture": Implications for behavioral health care in rural settings. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17(9):1256–1267. doi: 10.1177/1049732307307757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and longitudinal modeling using Stata. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp CA, Bond GR, Becker DR, Carpinello SE, Nikkel RE, Gintoli G. The role of state mental health authorities in promoting improved client outcomes through evidence-based practice. Community Ment Health J. 2005;41(3):347–363. doi: 10.1007/s10597-005-5008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refowitz M. San Diego County mental health system cultural competence assessment. San Diego: San Diego State University Foundation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Reichman JS. Immigration, acculturation and health: The Mexican diaspora. In: Gold SJ, Rumbaut RG, editors. The new Americans: Recent immigration and American society. New York: LFB Scholarly Publishing; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Research and Polling Inc. NMMRA/NM HSD behavioral health provider satisfaction study. Albuquerque, NM: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rost K, Fortney J, Fischer E, Smith J. Use, quality, and outcomes of care for mental health: The rural perspective. Med Care Res Rev. 2002;59(3):231–265. doi: 10.1177/1077558702059003001. discussion 266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]