Abstract

The purpose of this study is to see whether prayer helps older people cope more effectively with the adverse effects of lifetime trauma. Data from a nationwide survey of older adults reveal that the size of the relationship between traumatic events and depressive symptoms is reduced for older people who believe that only God knows when it is best to answer a prayer, and when they believe that only God knows the best way to answer it. The findings further reveal that these beliefs about prayer outcomes are especially likely to offset the effects of traumatic events that arose during childhood.

Keywords: Traumatic events, prayer, depressive symptoms

A number of researchers argue that one of the primary functions of religion is to help people cope more effectively with the adverse events that arise in their lives (Pargament, 1997). However, as research on the stress process continues to mature, it has become increasingly evident that people are faced with several different kinds of stressors (Wheaton, 1994). In order to fully understand the stress-buffering function of religion, researchers must explore the full spectrum of stressful experiences. So far, most of the research on religion and stress has focused on stressful life events. Stressful life events are distinguished from other types of adversity by their natural history. More specifically, stressful events tend to peak and dissipate within a relatively short time, typically within a year or so (Turner & Wheaton, 1995). Included among stressful life events are trouble with the boss, moving to a new neighborhood, and financial setbacks. More recently, researchers have become interested in studying whether religion helps people cope more effectively with another kind of stressor – traumatic events (e.g., Ai, Tice, Peterson, & Huang, 2005). Wheaton (1994) defines trauma as events that are “… spectacular, horrifying, and just deeply disturbing experiences (p. 90).” Included among traumatic events are sexual and physical abuse, witnessing a violent crime, the premature loss of a parent, and participation in combat. Traumatic events are distinguished from other types of stressors, such as stressful life events, by their imputed seriousness. And because they are so severe, a number of investigators have found that the deleterious effects of traumatic events can last a lifetime (Krause, Shaw, & Cairney, 2004).

The purpose of the current study is to see whether one specific facet of religion (i.e., prayer) helps older people cope more effectively with the deleterious effects of lifetime trauma. This appears to be the first time this issue has been examined with data provided by a nationwide sample of older adults.

The theoretical rationale for this study is developed below by discussing three challenges that face researchers who wish to learn more about the interface between traumatic events, prayer, and psychological distress. The first challenge involves whether to study single traumatic events or whether to study the joint influence of multiple traumatic experiences. The second dilemma has to do with seeing whether traumatic events that arise at specific points in the life course are especially consequential. The third quandary arises from conceptual and measurement issues in the study of religious coping responses. In the process of discussing each of these issues, an effort is made to show why it is important to evaluate these issues in samples comprising older people.

Studying Individual versus Multiple Traumatic Events

A number of researchers have studied the effects of single traumatic events on health and well-being. For example, some investigators have examined exposure to combat in Vietnam (e.g., Green, Lindy, & Grace, 1988) whereas others have focused on the bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma City in 1995 (Pargament, Smith, Koenig, & Perez, 1998). However, as a number of studies reveal, the average individual experiences nearly three traumatic events in his or her lifetime (Norris, 1992). Although researchers have clearly learned a great deal from studying each traumatic event by itself, it is time to consider a different way of measuring this type of stressor. If the effects of trauma last a lifetime, and if people experience several traumatic events, then the full effects of trauma are more likely to be captured with checklists that assess exposure to a range of different traumatic experiences. There do not appear to be any studies in the literature that assess whether religion helps older adults cope more effectively with the effects of multiple traumatic events that have arisen across the life course.

Bringing Life Course Issues to the Foreground

The second problem with research on religion and traumatic events has to do with life course developmental issues. Researchers have argued for some time that the impact of a traumatic event may depend on the age or developmental stage in which it is encountered (O'Connor, 2003). For example, some investigators maintain that the loss of a parent has a greater effect on mental health if it occurs prior to age 16 or so (e.g., Krause, 1993). Because many mental health problems arise relatively early in life (i.e., typically before young adulthood) (Kessler et al., 2005), the causes of these mental health difficulties are likely to be found relatively early in life, as well. As research by Kessler and his associates reveals, traumatic events arising during childhood may be an important etiological factor in the genesis of mental disorder (Kessler et al., 1997). If traumatic events promote mental health problems that arise early in life, and if religion helps people cope more effectively with trauma, then it follows that these stress-buffering effects should be especially evident when traumatic events that arise early in life are taken into consideration.

Although research on childhood trauma and mental health has provided some valuable insights, there is a problem with the way most of the research in this field has been conducted. So far, many of the investigators who assert that events that arise early in life have the greatest impact base their claim on data that have been provided primarily by adolescents and younger adults. But the only way to be sure that early childhood trauma exerts the greatest effect is to wait until people have traversed all of the major developmental stages and are well into old age. Otherwise, researchers cannot rule out the possibility that events arising in late life are more consequential. It is for this reason that studying lifetime trauma among older people is the focus of the current study. There do not appear to be any studies that are designed to see if religion is more likely to help older people cope with traumatic events that rise earlier in life than traumatic events that emerge later in the life course.

Issues in the Assessment of Religious Coping Responses

So far, the discussion of religion and lifetime trauma has focused solely on issues in the conceptualization and measurement of traumatic events. However, it is also important to consider issues in the conceptualization and measurement of religious coping because this is a vast conceptual domain in its own right. Researchers have used one of two broad strategies to study religious coping responses. The first approach involves assessing whether a wide array of religious coping responses offset the effects of various stressors on physical and mental health. So, for example, Pargament and his colleagues have devised an extensive inventory of religious coping responses ranging from coping methods that are designed to enhance feelings of control to coping responses that help people feel closer to God (Pargament, Koenig, & Perez, 2000). Researchers have learned a great deal from this approach to studying religious coping. However, there are some drawbacks associated with the study of multiple coping responses. This issue is perhaps best illustrated by focusing on the coping response that is the focal point of the current study. Researchers have known for some time that people often turn to prayer in order to deal with the adversities that confront them (e.g., Ai et al., 2005). However, prayer is a complex construct that can be measured in a number of ways. By far, the most common way of measuring prayer involves simply assessing how often people pray, but prayer can also be evaluated by focusing on the type of prayer that is offered (e.g., ritual prayer and petitionary prayer – see Poloma & Gallup, 1991), as well as the beliefs that people hold about the outcomes of the prayers they offer (Krause, 2004). Unfortunately, it is difficult to tease out the finer nuances of prayer when it is embedded in a larger checklist of religious coping responses. This problem arises because sufficient questionnaire space is often not available to conduct a detailed assessment of the various types of prayer, different uses of prayer, and different beliefs about prayer outcomes.

The current study was designed to take a more focused approach to the subject of religious coping by examining one particular coping response – prayer. Doing so makes it possible to highlight a facet of prayer that has not been considered previously within the context of the stress process. As noted above, the most common way to measure prayer involves simply asking study participants how often they pray when they are alone. However, as Blalock (1982) pointed out some time ago, embedded in every measurement strategy is a theoretical statement about how a construct operates. Cast within the context of the current study, this means that when investigators rely on measures of the frequency of prayer, they are assuming that the most important element of a prayer is how often it is offered, and that other facets of prayer, such as the type of prayer or the beliefs about prayer outcomes are of little consequence. This is a largely untested assumption that is not likely to be valid. The best way to see whether this is so is to empirically contrast the stress-buffering effects of the frequency of private prayer with the effects of other facets of prayer that speak more directly to the problems that are created by traumatic life events. This strategy is adopted in the analyses that follow.

A number of other investigators have focused specifically on the potential stress-buffering properties of prayer. In the process, they have moved beyond the use of simple prayer frequency measures. For example, Ai and her colleagues assess whether prayer helps people cope with pending cardiac surgery (Ai, Peterson, Bolling, & Koenig, 2002). Prayer is assessed in this study with a three-item index that asks study participants if prayer is important to them, if prayer helps them cope with the stressors they encounter, and if they intend to use prayer in order to cope with their upcoming surgery. This study clearly makes a number of important contributions to the literature. However, the items that are used to assess prayer are somewhat vague. These indicators reflect whether prayer is useful and important and whether study participants intend to use prayer as a coping resource, but it is still not clear how prayer offsets the deleterious effects of stress because these items do not explicitly capture what prayer actually does. In order to move research on the potential stress-buffering properties of prayer forward, it is important to identify the specific psychosocial deficits that are created by the type of stressor that is under investigation, and devise measures that reflect the ways in which prayer helps people confront these particular problems.

Gottlieb's (1997) insightful review of the stress process provides an important point of departure for thinking about how prayer helps people cope specifically with traumatic events. Gottlieb argues that religion may be especially helpful for dealing with stressors that cannot be altered or avoided. In many ways, traumatic events cannot be altered, avoided or resolved easily. This is especially true with respect to traumatic events that have arisen in childhood. By the time a person reaches late life, the traumatic events they encountered in childhood arose fifty or sixty years ago. As a result, there is relatively little that can be done about them. When stressors that cannot be altered have arisen, Gottlieb suggests that about all a person can do is accept the fact that the event happened and move on with his or her life. In fact, he maintains that doing so has important implications for dealing with other types of stressors: “… acceptance of the permanence of certain aspects of personal and environmental hardship may free the energy needed to deal with other demands or stressful conditions that are changeable” (Gottlieb, 1997, p. 27). The fact that many traumatic events cannot be altered or eradicated has important implications for studying the potential stress-buffering properties of prayer.

In the process of presenting his views on the resigned acceptance of unalterable events, Gottlieb (1997) makes an observation that can easily be overlooked. Specifically, he points out that different facets of religion, including prayer, may not just promote a sense of acceptance – instead, they may instill a sense of “peaceful acceptance” (p. 28). Some insight into the nature of peaceful acceptance may be found in Heiler's (1932) classic book on prayer. In this work, Heiler argues that when people pray, “The vehement emotions of anxiety, worry, depression, mourning dissolve away in the gentle mood of trust, good hope, resignation” (p. 294). Unfortunately, Gottlieb (1997) never explains precisely what he means by peaceful acceptance nor does he provide a clear sense of how a feeling of peaceful acceptance may arise. A central premise in the current study is that certain beliefs about the way prayers are answered may play an important role in bringing this about. Research on prayer by Krause (2004) reveals that some people believe that God answers prayers right away, and they believe they often get exactly what they ask for when they pray. In contrast, Krause (2004) reports that other individuals believe that it is important to learn to wait for an answer to a prayer because only God knows when it is best to respond, and they believe that God often answers prayers in ways other than they expected or requested. When viewed from a wider vantage point, the prayer beliefs of this later group of individuals reflect a deep and abiding sense of trust in God, and a strong belief that He will provide exactly what they need even though they may not fully appreciate what is in their own best interest. It should be easier for people who take this approach to prayer to accept the traumatic events they have encountered because their faith leads them believe that God will take care of things for them. But more than this, the sense of trust, hope, and assurance that arises from these prayer beliefs is likely to foster the sense of peaceful acceptance that is identified by Gottlieb (1997).

Based on the theoretical rationale that has been developed above, it is proposed that current trust-based prayer beliefs will offset the pernicious effects of lifetime traumatic events on psychological distress in late life. Moreover, it is hypothesized that the stress-buffering effects of trust-based prayer beliefs will be especially evident when traumatic events that have arisen during childhood are assessed.

Methods

Sample

The data for this study come from an ongoing nationwide survey of older Whites and older African Americans. The study population was defined as all household residents who were either Black or White, non-institutionalized, English-speaking, and at least 66 years of age. Geographically, the study population was restricted to all eligible persons residing in the coterminous United States (i.e., residents of Alaska and Hawaii were excluded). Finally, the study population was restricted to practicing Christians, people who were Christian in the past but no longer practice any religion, and individuals who were not affiliated with any faith at any point in their lifetime. This study was designed to explore a range of issues involving religion. As a result, individuals who practice a faith other than Christianity were excluded because the members of the research team felt it would be too difficult to devise a comprehensive battery of religion measures that would be suitable for individuals of all faiths.

The sampling frame consisted of all eligible persons contained in the beneficiary list maintained by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). A five-step process was used to draw the sample from the CMS files. A detailed discussion of these steps is provided by Krause (2002).

The baseline survey took place in 2001. The data collection for this study was performed by Harris Interactive (New York). A total of 1,500 interviews were conducted, face-to-face, in the homes of the study participants. Elderly African Americans were oversampled so that sufficient statistical power would be available to assess race differences in religion. As a result, the Wave 1 sample contained 749 older Whites and 752 older Blacks. The overall response rate for the baseline survey was 62%.

The Wave 2 survey was conducted in 2004. A total of 1,024 of the original 1,500 study participants were re-interviewed successfully, 75 refused to participate, 112 could not be located, 70 were too ill to participate, 11 had moved into a nursing home, and 208 were deceased. Not counting those who had died or were living in a nursing home, the re-interview rate for the Wave 2 survey was 80%.

A third wave of interviews was completed in 2007. A total of 969 older study participants were re-interviewed successfully, 33 refused to participate, 118 could not be located, 17 were to sick to take part in the interview, and an additional 155 older people had died. Not counting those who either died or were in a nursing home, these figures reveal that approximately 86% of the older adults who participated in Wave 1 were successfully re-interviewed at Wave 3.

The data used in the analyses presented below come from the Wave 3 interviews only because this was the first time that information on exposure to lifetime trauma was obtained. A range of analyses are performed below. After using listwise deletion to deal with item nonresponse, complete data were available for between 869 and 784 older people. Preliminary analyses revealed that the average age of the participants in the group consisting of 869 respondents was 78.7 years (SD = 5.9 years) at Wave 3. Approximately 53.7% were White, 37% were men, and 44% reported they were married at the time the Wave 3 interviews were conducted. Finally, these study participants indicated they had successfully completed an average of 11.9 years of schooling (SD = 3.4 years). These descriptive data, as well as the data that are used in the analyses presented below, have been weighted. Separate weights were devised for older Whites and older Blacks. Within each racial group, the data were weighted so that the age, gender, and education of the study participants match the age, gender, and education reported in the most recent Census.

Measures

Table 1 contains the core measures that are used in the analyses that were conducted for this study. The procedures used to code these indicators are reported in the footnotes of this table.

Table 1.

Core Study Measures

|

A measure of lifetime trauma was created by simply summing the number of traumatic events that a respondent had experienced. A measure of childhood trauma was created by summing the number of traumatic events that a respondent encountered before they were 18 years of age.

These items were scored in the following manner (coding in parentheses): Strongly disagree (1); disagree (2); agree (3); strongly agree (4).

This item was scored in the following manner: Never (1); less than once a month (2); once a month (3); a few times a month (4); once a week (5); a few times a week (6); once a day (7); several times a day (8).

These items are scored in the following manner: Rarely or none of the time (1); some or a little of the time (2); occasionally or a moderate amount of the time (3); most or all of the time (4).

Traumatic life events

The older people in this study were presented with a checklist of 25 traumatic life events. This checklist was assembled from several sources, including the work of Wheaton, Roszell, and Clark (1997), Turner and Lloyd (1995), and the traumatic events listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 1994, p. 424). The participants in the current study were asked if they had ever experienced each of these events at any time in their life. If they reported that they had been exposed to a traumatic event, they were asked to report their age when they first encountered the stressor.

Two measures of trauma were created from responses to this checklist. The first measure reflects a simple count of the total number of traumatic events that an older person experienced in their entire lifetime. Consistent with the research of Norris (1992), preliminary analysis revealed that the older people in the current study experienced an average of 2.2 traumatic events (SD = 1.9 events) over the course of their lives. The second trauma measure consists of the total number of traumatic events that an older person encountered before the age of 18. The mean for this childhood trauma measure was .59 events (SD = .83 events). Preliminary analyses revealed that 42.8% of the older participants in this study experienced one or more traumatic events when they were 17 years of age or younger.

Prayer

Prayer is measured in two ways in the current study. As shown in Table 1, the first measure reflects how often people pray in private (0 = 6.8, SD = 1.8). A high score on this measure indicates that an older person prays more often when they are alone. The second measure, which was developed by Krause (2004), assesses trust-based prayer beliefs. This construct is measured with two items. Consistent with the theoretical rationale that was developed earlier, the first indicator asks respondents about the importance of waiting for God's answers to prayers, whereas the second item asks whether God gives people what is best for them. In essence, these measures capture the cognitions, or mind-set that is necessary for the emergence of the sense of peaceful acceptance that was identified by Gottlieb (1997). The bivariate correlation between these indicators is .699 (p < .001). A high score on this measure represents older respondents with stronger trust-based prayer beliefs.

A word is in order about how the trust-based prayer belief items were administered. The study participants were asked the question about the frequency of prayer. In the process of answering this question, 47 older study participants indicated that they never pray. A question was also asked about whether older people believe their prayers are answered. A total of 10 older adults reported that they felt their prayers were never answered. The items assessing trust-based prayer beliefs were not administered to the individuals in either of these groups because it did not make sense to ask about the way God answers prayers if older people either do not pray, or do not believe their prayers are answered.

Depressive symptoms

Eight items were taken from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) to assess depressive symptoms (Radloff, 1977). A confirmatory factor analysis (not shown here) revealed that these indicators reflect two underlying factors or dimensions. The first, which assesses a depressed affect, reflects the cognitive-affective aspects of depressive symptomatology, including feeling sad, blue, and depressed. The second factor, (somatic symptoms) captures the physiological manifestations of psychological distress including difficulty sleeping, having a poor appetite, and having little energy. The results of this confirmatory factor analysis are consistent with findings from other studies of the CES-D Scale that have been conducted with samples of older people (e.g., Hertzog et al., 1990). Two separate outcome measures were created based upon these results. A high score on either measure denotes greater depressive symptomatology. The internal consistency reliability estimate for the depressed affect measure (0 = 5.8; SD = 2.7) is .898, and the reliability of the brief composite assessing somatic symptoms of depression (0 = 6.6; SD = 3.1) is .845.

Frequency of church attendance

The relationships among lifetime trauma, prayer, and depressive symptoms were evaluated after the effects of the frequency of church attendance were controlled statistically. This control variable was assessed with a single item that asks study participants how often they attend formal worship services at church. A high score represents more frequent church attendance (0 = 5.5; SD = 2.9).

Demographic control variables

Measures of age, sex, education, race, and marital status were used as demographic control variables in all analyses presented below. Age is scored continuously in years and the measure of education reflects the total number of years of schooling completed successfully by study participants. In contrast, sex (1 = men; 0 = women), race (1 = White; 0 = Black), and marital status (1 = currently married; 0 = otherwise) were scored in a binary format.

Results

The findings from this study are presented below in three main sections. First, when the sample for this study was introduced, it was reported that some subjects who participated in the baseline survey did not participate in the follow-up interviews. Even though the substantive analyses for this study are based solely on the Wave 3 data, the loss of study subjects prior to that time may, nevertheless, bias study findings if this loss occurs non-randomly. Consequently, the analyses presented in the first section were conducted in order to assess this potential problem. Following this, findings from the substantive analyses that were designed to assess the relationships among trust-based prayer beliefs, lifetime trauma, and depressive symptoms are presented in section two. Section three contains the results of the analyses that were performed in order to evaluate the relationships among the frequency of private prayer, traumatic life events, and depressive symptoms in late life.

Evaluating the Effects of Sample Attrition

Although it is difficult to determine the precise effect of the loss of subjects over time on study findings, some preliminary insight can be obtained by seeing whether older people who were lost to follow-up differ significantly from older people who participated in the Wave 3 survey on select baseline study measures. The following procedures were used to examine this issue. First, a nominal level variable was created by assigning a score of 1 to older people who participated in the Wave 3 survey, a score of 2 was given to older adults who dropped out of the study between Wave 1 and Wave 3 but were presumed to be alive, and a score of 3 was assigned to older individuals who had died. Then, using multinomial logistic regression, this nominal outcome variable was regressed on the following Wave 1 study measures: Age, sex, education, marital status, race, the frequency of church attendance, the frequency of private prayer, trust-based prayer beliefs, depressed affect, and somatic symptoms of depression. Older people who participated in the Wave 3 interviews were used as the reference group in this model.

The findings (not shown here) suggest that, compared to older people who remained in the study, older adults who dropped out prior to Wave 3 were less likely to be White (b = !.611; p < .01; odds ratio = .543), less likely to be married (b = !.827; p < .001; odds ratio = .428), less likely to attend church often (b = !.114; p < .01; odds ratio = .892), and less likely to experience somatic symptoms of depression (b = !.104; p < .05; odds ratio = .901).

The data further reveal that, compared to older people who remained in the study, older individuals who died were more likely to be men (b = .636; p < .001; odds ratio = 1.889), older (b = .079; p < .001; odds ratio = 1.082), less likely to attend church often (b = !.096; p < .01; odds ratio = .909), and more likely to endorse trust-based prayer beliefs (b = .200; p < .05; odds ratio = 1.222).

Taken together, the findings from the sample attrition analysis suggest that the loss of subjects over time did not occur in a random manner. However, there is considerable debate in the literature about whether study findings are biased under these circumstances (see Groves et al., 2004, for a discussion of this controversy). Because this issue cannot be resolved in the current study, it is best to keep the potential influence of non-random sample attrition in mind as the substantive findings are reviewed.

Traumatic Events, Trust-Based Prayer Beliefs, and Depressive Symptoms

Trauma across the entire life course

Findings from the analyses that were designed to assess the relationships among retrospective reports of trauma that arose at any point in the life course, current trust-based prayer beliefs, and current levels of depressive symptoms are presented in Table 2. Based on the theoretical rationale that was developed for this study, it was hypothesized that the deleterious effects of lifetime trauma on depressive symptoms would be offset for older people who strongly adhere to trust-based prayer beliefs. Stated in more technical terms, this hypothesis predicts that there will be a statistically significant interaction effect between lifetime trauma and trust-based prayer beliefs on depressive symptoms. Tests of this hypothesis were performed with a hierarchical ordinary least squares multiple regression analysis consisting of two steps. In the first step (i.e., Model 1) measures of lifetime trauma, trust-based prayer beliefs, the frequency of church attendance, and the demographic control variables were entered into the equation. Then, a multiplicative term was added in Step 2 (i.e., Model 2) that was created by multiplying lifetime trauma scores by scores on the measure of trust-based prayer beliefs. This cross-product term tests for the proposed statistical interaction effect.

Table 2.

Trust-Based Prayer Beliefs, Lifetime Trauma, and Depression (N = 784)

| Depressed Affect | Somatic Symptoms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 |

| Age | .096**a | .093** | .106*** | .104** |

| (.045)b | (.044) | (.057) | (.056) | |

| Sex | !.152*** | !.156*** | !.083* | !.085* |

| (!.871) | (!.890) | (!.543) | (!.559) | |

| Education | !.025 | !.024 | !.009 | !.009 |

| (!.020) | (!.019) | (!.009) | (!.009) | |

| Race | .045 | .044 | .057 | .056 |

| (.248) | (.242) | (.359) | (.353) | |

| Marital status | .060 | .065 | .053 | .056 |

| (.335) | (.362) | (.335) | (.356) | |

| Church attendance | !.277 | !.272*** | !.289*** | !.286*** |

| (!.264) | (!.259) | (!.317) | (!.313) | |

| Prayer beliefs | !.027 | !.032 | !.003 | !.006 |

| (!.070) | (!.083) | (!.010) | (!.018) | |

| Lifetime trauma | .087** | .098** | .096** | .103** |

| (.124) | (.139) | (.156) | (.167) | |

| Lifetime trauma X prayer beliefs | …… | …… | …… | |

| …… | (!.103)* | (!.073) | ||

| Multiple R2 | .125 | .130 | .120 | .122 |

Standardized regression coefficient

Metric (unstandardized) regression coefficient

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

The data provided in the far left-hand column of Table 2 reveal that older people who experience more traumatic events over the course of their lives tend to report more depressed affect symptoms than older adults who encountered fewer traumatic events in their lifetime (Beta = .087; p < .01). In contrast, greater endorsement of trust-based prayer beliefs does not appear to be associated with depressed affect scores (Beta = !.027; ns). The same findings emerge when somatic symptoms of depression are used as the outcome measure. More specifically, the data in column three suggest that exposure to more traumatic events over the life course is associated with more somatic symptoms of depression (Beta = .096; p > 01), whereas trust-based prayer beliefs are not significantly associated with this outcome measure (Beta = !.003; ns).

The data in columns 2 and 4 of Table 2 are of greater interest because they contain the results of the tests for the proposed statistical interaction effect. The findings from these analyses are mixed. As the data in column 2 reveal, there is a statistically significant interaction effect between lifetime trauma and trust-based prayer beliefs on depressed affect scores (b = !.103; p < .05), but the same is not true when somatic symptoms serve as the outcome measure (b = !.073; ns; unstandardized coefficients are presented when interaction effects are reviewed because standardized estimates are meaningless in this context). Taken together, these findings would appear to provide only modest support for the notion that trust-based prayer beliefs are an important resource for coping with the effects of traumatic life events. Fortunately, a more compelling set of results emerges when the analyses involve traumatic events that arose during childhood.

Childhood trauma

Table 3 contains the findings from the analyses that were conducted to see if trust-based prayer beliefs help older people cope more effectively with the effects of traumatic events that arose before they were 18 years of age. The data in column one suggest that both childhood trauma (Beta = .040; ns) and trust-based prayer beliefs (Beta = !.019; ns) are not significantly associated with depressed affect scores in late life. The same results emerge when somatic symptoms serves as the dependent variable (childhood trauma Beta = .013; ns; trust-based prayer beliefs Beta = .006; ns).

Table 3.

Trust-Based Prayer Beliefs, Childhood Trauma, and Depression (N = 784)

| Depressed Affect | Somatic Symptoms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 |

| Age | .091**a | .087** | .101** | .098** |

| (.043)b | (.041) | (.054) | (.053) | |

| Sex | !.147*** | !.152*** | !.078* | !.081* |

| (!.844) | (!.868) | (!.512) | (!.532) | |

| Education | !.017 | !.015 | !.002 | .001 |

| (!.014) | (!.012) | (!.002) | (.001) | |

| Race | .047 | .053 | .058 | .061 |

| (.260) | (.290) | (.363) | (.380) | |

| Marital status | .051 | .046 | .042 | .039 |

| (.283) | (.253) | (.267) | (.247) | |

| Church attendance | !.279*** | !.269*** | !.293*** | !.288*** |

| (!.266) | (!.257) | (!.321) | (!.315) | |

| Prayer beliefs | !.019 | !.020 | .006 | .005 |

| (!.048) | (!.052) | (.019) | (.016) | |

| Childhood trauma | .040 | .039 | .013 | .012 |

| (.127) | (.126) | (.049) | (.046) | |

| Childhood trauma X prayer beliefs | …… | …… | …… | …… |

| …… | (!.471)*** | …… | (!.359)*** | |

| Multiple R2 | .119 | .147 | .112 | .124 |

Standardized regression coefficient

Metric (unstandardized) regression coefficient

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

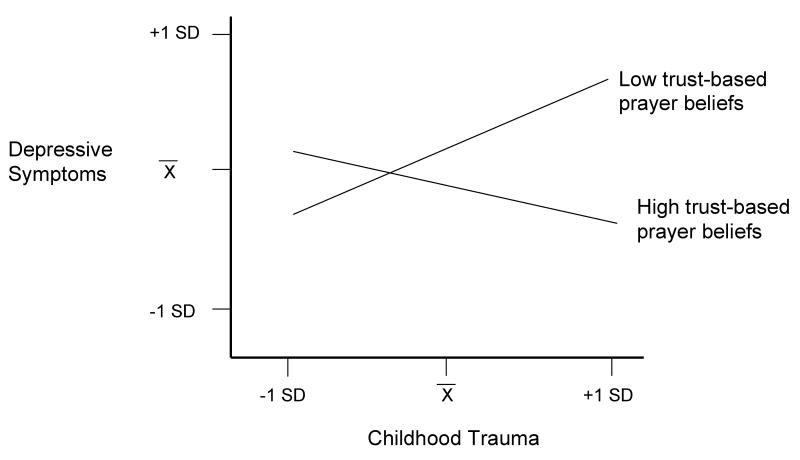

In contrast to the findings that have emerged so far, the data further suggest that there is a statistically significant interaction effect between childhood trauma and trust-based prayer expectancies on depressed affect scores (b = !.471; p < .001) and somatic symptoms of depression (b = !.112; p < .001). Although the results reveal that there are statistically significant interaction effects in the data, it is somewhat difficult to tell if these interactions are in the hypothesized direction. Fortunately, it is possible to address this issue by using the formulas that are provided by Aiken and West (1991) to estimate the effects of childhood trauma on depressive symptoms at select levels of trust-based prayer beliefs. If the theoretical rationale that was developed for this study is valid, the effects of childhood trauma on depressive symptoms should become progressively weaker at successively higher levels of trust-based prayer beliefs. Scores on the measure of trust-based prayer beliefs range from 4 to 8. Although any value in this range can be used to illustrate the observed interaction effects, values of 4, 6, and 8 were selected for this purpose. Even though significant interaction effects emerged with both the depressed affect and somatic symptom outcomes, only the data from the analyses involving depressed affect scores will be used to illustrate the nature of the observed interaction effects.

The additional calculations (not shown here) suggest that traumatic events that arose during childhood are associated with elevated depressed affect scores for older people who have relatively weak trust-based prayer beliefs (i.e., older people with a trust-based belief score of 4) (Beta = .478; b = 1.529; p < .001). Childhood trauma also appears to exert a detrimental influence on depressed affect scores for older people with stronger trust-based prayer belief scores (i.e., a score of 6), but the size of the relationship has been reduced by about 62 percent (Beta = .183; b = .587; p < .001). And perhaps more importantly, the additional calculations suggest that among older people with the highest possible trust-based belief scores (i.e., a value of 8), greater exposure to childhood trauma is associated with fewer depressive affect symptoms (Beta = !.111; b = !.355; p < .05). A graph was created (see Figure 1) to further illustrate the nature of the observed interaction effect between childhood trauma and trust-based prayer beliefs on depressive symptoms.

Figure 1.

Illustrating the Statistical Interaction between Childhood Trauma and Trust-Based Prayer Beliefs on Depressed Affect Scores

Traumatic Events, the Frequency of Private Prayer, and Depressive Symptoms

The findings that have been provided up to this point suggest that trust-based prayer beliefs may be an important resource for coping with the pernicious effects of traumatic events that arose during childhood. However, it is important to see if these stress-buffering effects can be attributed to trust-based prayer beliefs, per se, and not some other facet of prayer that is correlated with it. It is not possible to conduct a comprehensive assessment of this issue because data on a complete range of prayer measures are not available in this study. Nevertheless, some preliminary insight into this issue may be found by seeing whether the same stress-buffering effects emerge when another dimension of prayer (i.e., the frequency of private prayer) is used in the analyses. The frequency of private prayer is suitable for this purpose because, as noted earlier, it is the most widely used measure of prayer and because it is significantly correlated with the measure of trust-based prayer beliefs (r = .387; p < .001).

The analyses that were discussed in the previous section were repeated after the measure of the frequency of private prayer was used in place of the measure of trust-based prayer beliefs. Two sets of analyses were performed. The first set was designed to see whether more frequent private prayer offsets the effects of traumatic events that arose at any point in the life course on depressive symptoms. The findings (not shown here) suggest that the size of the relationship between lifetime trauma and depressed affect scores is not reduced significantly for older people who pray often (i.e., a statistically significant interaction effect failed to emerge from the analyses; b = .007; ns). Similarly, the data further reveal that the frequency of private prayer does not significantly offset the deleterious effects of lifetime trauma on somatic symptoms of depression (b = .011; ns) (tables containing the results of these analyses are available upon request from the author).

The second set of analyses was designed to see whether more frequent private prayer buffers the effects of traumatic events that were encountered during childhood on symptoms of depression in late life. Little support for this alternative hypothesis was found in the data. More specifically, a statistically significant interaction effect between childhood trauma and the frequency of private prayer failed to emerge from the data when either depressed affect scores (b = .024; ns) or somatic symptoms (b = .026; ns) served as the outcome measure.

Discussion

Martin Luther maintained that faith is “… prayer and nothing but prayer” (as quoted in Heiler, 1932, p. iii). Since that time, a number of other investigators have expressed a similar view. For example, William James argued that prayer is “… the very soul and essence of religion” (James, 1902/1997, p. 486). Describing prayer as “… religion in action …,” James believed that prayer is the arena in which the work of religion is done (1902/1997, p. 486). If one of the primary goals of religion is to help people deal with adversity (Pargament, 1997) and prayer is the very essence of religion, then it follows that prayer should perform a significant stress-buffering function. The purpose of the current study was to explore this possibility. The findings suggest that prayer may, indeed, help older people cope more effectively with the stressors that arise in life. Although other investigators have come to a similar conclusion (e.g., Copeland-Linder, 2006), an effort was made to contribute to the literature in three potentially important ways. First, an attempt was made to expand the scope of inquiry by seeing whether prayer helps older individuals cope more effectively with traumatic events that have arisen across the life course. The data suggest that this may be so. These results are noteworthy because this appears to be the first time that the interface between prayer and a comprehensive measure of lifetime trauma has been evaluated. Second, the findings from the current study were extended by seeing whether prayer helps older people cope with traumatic events that arose specifically during childhood. The results suggest that prayer may be especially effective in this respect. This appears to be the first time that the relationships among prayer, childhood trauma, and depressive symptoms have been evaluated with data provided by older people. These results provide dramatic evidence of the lifelong influence of childhood experiences because in this instance, the childhood events that were encountered by the participants in this study emerged, on average, about sixty years ago. Third, the results indicate that some types of prayer (i.e., trust-based prayer beliefs) are more likely to offset the effects of childhood trauma than other types of prayer (i.e., the frequency of private prayer). This is the first time that the potential stress-buffering effects of trust-based prayer beliefs have been evaluated empirically.

One finding that emerged from the current study may seem somewhat surprising. Recall that at the highest level of trust-based prayer beliefs, greater exposure to traumatic events during childhood is associated with fewer symptoms of depression. There is a straightforward explanation for this seemingly counterintuitive finding. For some time now, scholars who study traumatic events have argued that rather than resulting solely in negative outcomes, exposure to trauma can provide an opportunity for significant personal growth as well (e.g., Bonanno, 2004). As Tedeschi and Calhoun (2004) observe, “The evidence is overwhelming that individuals facing a wide variety of very difficult circumstances experience significant changes in their lives that they view as highly positive” (p. 3). McMillen (1999) discusses how this may happen. More specifically, he argues that wrestling with adverse experiences may increase a person's sense of meaning in life; it may help them either gain new coping skills or realize they had coping skills they didn't know they possessed; and the support they receive from others may help them more deeply appreciate the loved ones who surround them. In addition, as Koenig (1994) points out, grappling with adversity may also provide an opportunity to deepen one's faith.

Although the findings from this study may have contributed to what researchers know about the interface between prayer and stress, a great deal of work remains to be done. For example, prayer is a complex multidimensional construct that can be measured in a number of ways. To date, no one has conducted a comprehensive study with a full complement of prayer measures to see which types of prayer are more likely to offset the pernicious effects of stress. It may turn out that no one type is more efficacious than another. Instead, some types of prayer may be more likely to offset the effects of certain types of stressors, whereas other types of prayer may be more likely to help people cope with differing stressful experiences. As noted earlier, greater insight might be gained by matching the benefits provided by specific types of prayer with the psychosocial deficits that are created by particular types of stressors.

It is also important to delve more deeply into the study of trust-based prayer beliefs. According to the theoretical rationale that was developed for this study, trust-based prayer beliefs help reduce the effects of traumatic life events by instilling a sense of peaceful acceptance. However, a measure of peaceful acceptance was not available in the data. Consequently, it is important to derive measures of this intervening construct and see whether it explains how the potentially beneficial effects of trust-based prayer beliefs arise.

It would also be important for researchers to explore other aspects of religion that help promote a sense of peaceful acceptance. This research may reveal, for example, that the same positive emotions are likely to arise from engaging in religious rituals as well as scriptural study.

Researchers would also benefit from assessing the relationships among childhood trauma, trust-based prayer beliefs, and depressive symptoms in other cultures and other religions. For example, in their insightful book about religion in Japan, Reader and Tanabe (1998) report that the Japanese frequently pray for practical or worldly things, such as job promotions and academic success for their children. It would be enlightening to see whether the Japanese hold views about prayer outcomes that are similar to those reported in the current study. Moreover, it would be important to discover if the prayer belief outcomes they endorse help them cope more effectively with the effects of stress.

Researchers should also pay more careful attention to the measurement of lifetime trauma. One of the traumatic events that were assessed in the current study has to do with the unexpected death of a spouse. However, inventories of stressful life events typically include the death of a spouse, as well. Clearly, it is not possible to resolve longstanding problems in stress measurement here, but resolving these issues should be a high priority in the future.

In the process of examining these, as well as other issues, it is important for researchers to keep the limitations of the current study in mind. Four shortcomings may be found in the work that was presented above. First, the data are cross-sectional. As a result, it cannot be demonstrated conclusively that traumatic events “cause” depressive symptoms or that prayer plays a role in reducing these deleterious effects. These issues can only be addressed with studies that employ a true experimental design. However, it is difficult to see how an experiment can be devised to assess the effects of childhood trauma on depressive symptoms among older people.

Second, information on trauma across the life course was obtained through self-report. There is tremendous controversy in the literature over the reliability and validity of retrospective reports of lifetime trauma. Some investigators maintain that these self-reports are seriously flawed (e.g., Maughan & Rutter, 1997), but others disagree. For example, Bernstein and his colleagues conclude that fears about retrospective reports, especially reports about childhood events, are exaggerated and that these self-reports are “… generally stable over time, show good agreement with reports of other informants (e.g., siblings), and are often verified when archival data are available” (Bernstein et al., 1994, p. 1136). There is clearly no way to resolve this issue with the data that are available in the current study. In fact, the only way to conclusively resolve this issue is to conduct a prospective study that encompasses the entire life course, ranging from childhood to old age. However, as Kessler et al. (1997) point out, such a study would be prohibitively expensive.

The third limitation in this study is closely related to the second. The respondents in the current study were asked to provide two specific pieces of information: They were asked if they encountered a traumatic event and they were asked to report how old they were when they first encountered a traumatic event. This raises the possibility that an older study participant could accurately report that he or she experienced a traumatic event, but fail to provide accurate information about how old they were when this first happened. Although there do not appear to be any studies in the literature that explore the extent of this problem, the potential bias arising from the inaccurate dating of lifetime traumas should be kept in mind as the findings from this study are reviewed.

The fourth shortcoming in this study also has to do with the way that the data on traumatic events were obtained. Respondents were asked to only report the first time they experienced a traumatic event, but as the research of Breslau and her colleagues reveals, people may experience the same traumatic event more than once (Breslau, Chilcoat, Kessler, & Davis, 1999). So, for example, a person may be sexually or physically abused more than once. To the extent this is true, reports about the relationship between trauma on depressive symptoms in the current study are likely to be underestimated.

At its base, prayer rests upon and is sustained by belief. But whether beliefs about prayer are valid is of little concern because there is no way they can be verified. Instead, the primary concern lies with the intensity and commitment to these beliefs, as well as their impact on behavior and the quality of life. As W. I. Thomas so aptly put it, “If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences” (Thomas & Thomas, 1928, p. 572). When viewed at the broadest level, the current study was designed to assess both the intensity of beliefs about prayer and how these beliefs shape the way older people handle more extreme types of adversity. And as the findings reveal, the consequences of these beliefs are very real indeed.

Acknowledgments

Author's Note: This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG014749).

References

- Ai AL, Peterson C, Bolling SF, Koenig H. Private prayer and optimism in middle-aged patients awaiting cardiac surgery. The Gerontologist. 2002;42:70–81. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai AL, Tice TN, Peterson C, Huang B. Prayers, spiritual support, and positive attitudes in coping with the September 11 national crisis. Journal of Personality. 2005;73:763–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, Sapareto E, Ruggiero J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of childhood abuse and neglect. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blalock HM. Conceptualization and measurement in the social sciences. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience. American Psychologist. 2004;59:20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Chilcoat HD, Kessler RC, Davis GC. Previous exposure to trauma and PTSD effects of subsequent trauma: Results from the Detroit Area Study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:902–907. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland-Linder N. Stress among black women in a South African township: The protective role of religion. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;34:577–599. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb BH. Conceptual and measurement issues in the study of coping with chronic stress. In: Gottlieb BH, editor. Coping with chronic stress. New York: Plenum; 1997. pp. 3–40. [Google Scholar]

- Green BL, Lindy JD, Grace MC. Long-term coping with combat stress. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1988;1:399–412. [Google Scholar]

- Groves RM, Fowler FJ, Couper MP, Lepkowski JM, Singer E, Tourangeau R. Survey methodology. New York: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Heiler F. Prayer: A study in the history and psychology of religion. New York: Oxford University Press; 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog C, Van Alstine J, Usala PD, Hultsch DF, Dixon R. Measurement properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in older populations. Psychological Assessment. 1990;2:64–72. [Google Scholar]

- James W. William James: Selected writings. New York: Book-of-the-Month Club; 19021997. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Gillis-Light J, Magee WJ, Kendler KS, Eaves LJ. Childhood adversity and adult psychopathology. In: Gotlieb IH, Wheaton B, editors. Stress and adversity over the life course: Trajectories and turning points. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–603. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG. Aging and God. New York: Haworth Pastoral Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Early parental loss and personal control in late life. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1993;48:P117–P126. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.3.p117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Church-based social support and health in old age: Exploring variations by race. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2002;57B:S332–S347. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.s332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Assessing the relationships among prayer expectancies, race, and self-esteem in late life. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2004;43:395–408. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Shaw BA, Cairney J. A descriptive epidemiology of lifetime trauma and the physical health status of older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2004;19:637–648. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.4.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maughan B, Rutter M. Retrospective reporting of childhood adversity: Issues in assessing long-term recall. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1997;11:19–33. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1997.11.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen JC. Better for it: How people benefit from adversity. Social Work. 1999;44:455–468. doi: 10.1093/sw/44.5.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH. Epidemiology of trauma: Frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:409–418. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor TG. Early experiences and psychological development: Conceptual questions, empirical illustration, and implications for intervention. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:671–690. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice. New York: Guilford; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Perez LM. The many methods of coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;56:519–543. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(200004)56:4<519::aid-jclp6>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Smith BW, Koenig HG, Perez L. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1998;37:710–724. [Google Scholar]

- Poloma MM, Gallup GH. Varieties of prayer: A survey report. Philadelphia: Trinity Press International; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reader I, Tanabe GJ. Practically religious: Worldly benefits and the common religion of Japan. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry. 2004;15:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas WI, Thomas DS. The child in America: Behavioral problems and programs. New York: Knopf; 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Lloyd DA. Lifetime trauma and mental health: The significance of cumulative adversity. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36:360–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Wheaton B. Checklist measurement of stressful life events. In: Cohen S, Kessler RC, Gordon LU, editors. Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 29–58. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B. Sampling the stress universe. In: Avison WR, Gotlieb IH, editors. Stress and mental health: Contemporary issues and prospects for the future. New York: Plenum; 1994. pp. 77–114. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B, Roszell P, Hall K. The impact of twenty childhood and adult traumatic stressors on the risk of psychiatric disorder. In: Gotlieb IH, Wheaton B, editors. Stress and adversity over the life course. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 50–72. [Google Scholar]