Drug recycling seems a more elegant solution than simply flushing pharmaceuticals down the toilet to work their way into watersheds, various flora or fauna and eventually back into the human food chain.

In fact, 38 of the United States have now accepted that rationale and adopted some manner of drug recycling or redistribution programs for the estimated 3%–7% of pharmaceutical products that go unused because patients are cured, die or, for reasons such as undesirable side effects, discontinue their medications.

The US programs vary in scope, inclusivity and restrictions. Some accept drug donations from patients or family members of the deceased. Others limit donations to health facilities. Some accept only cancer drugs while others accept all prescription drugs or all unused medications. As a general rule, though, the intent is to redistribute unused drugs to needy people who simply cannot afford them.

In Canada, by contrast, there are only a few fledgling efforts to recycle drugs and a raft of regulatory or legislative obstacles to creating such programs. But it appears that Dr. Jeff Turnbull, one of the founders of the Ottawa, Ontario-based Inner City Health Project and the president-elect of the Canadian Medical Association, has managed to sidestep the obstacles with a program for the homeless, while Nova Scotia oncologist Dr. Ronald McCormick hopes to soon establish a pilot project for recycling cancer drugs.

“There still seems to be a ludicrous waste of drugs, particularly drugs that are well-documented in terms of the safety of them,” says McCormick, medical director of the Cape Breton Cancer Centre in Sydney, Nova Scotia. “It’s crazy.”

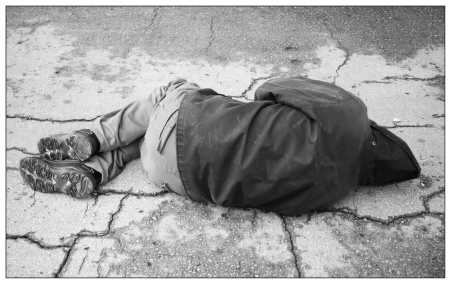

The homeless in Ottawa, Ontario, are one of the recipient groups of a drug recyling program established by CMA President-elect Dr. Jeff Turnbull as part of the Inner City Health Project.

But the fact remains that all provinces have some manner of legislation or regulation that prohibits redispensing of previously prescribed drugs, typically on the grounds of safety. In the US, some states distinguish between drugs that are donated by individuals (and thus supposedly more prone to tampering) and those donated by health facilities, practitioners, pharmaceutical firms, pharmacies or representatives of various medical facilities.

Turnbull tapped that distinction by establishing a program within the Inner City Health Project to dispense, to the homeless, unused prescription drugs donated by pharmacies or hospitals. Overstocked medical facilities donate excess supply, which is then examined by a pharmacist and approved for redistribution, Turnbull says.

MacCormick hopes to soon obtain legislative approval for a similar program. To that end, he recently established a partnership with a local community development group, New Dawn, that will seek to persuade facilities such as nursing homes to donate drugs, a pharmacy to monitor the incoming drugs and social workers to identify patients in need. Donations from private individuals will be precluded because some drugs require special care, he says.

There’s no doubt there’s a broader public benefit to such a program, says MacCormick. He and other proponents argue that recycling drugs would help to ensure that lower-income Canadians who can’t afford third party insurance have access to expensive cancer therapies. In the US, many of the programs were established as means of alleviating the cost of treating uninsured people in emergency rooms or clinics, which is essentially a moot point in Canada because drugs used in emergency departments are generally covered by Medicare. But a recycling program in Canada could help to alleviate the cost of catastrophic drug coverage programs, which most provinces now have some form of to assist people hit with extraordinary pharmaceutical bills.

Objections to recycling programs have largely been based on the argument that patient safety, and the profit margins of the pharmaceutical industry, would be compromised.

In the US, some programs prohibit donations from individuals in the interests of ensuring that the drugs have not been adulterated. Others allow individual donations but have various requirements regarding packaging, as well as various mechanisms for examining drugs after they’ve been donated. Some states allow recycled drugs to be dispensed directly to patients, while others funnel the donations to authorized pharmacies or medical facilities.

There’s been no evidence that safety has been compromised in the roughly three years that the Iowa Prescription Drug Corporation has been distributing recycled drugs to eligible medical facilities or to uninsured, underinsured or impoverished patients, says David Fries, executive director of the nonprofit corporation.

Nor does it appear that such programs constitute an enormous threat to profit margins. In Iowa, for example, roughly $US1 million worth of drugs were recycled in 2009, which would barely register on the bottom lines of Big Pharma, Fries says.

The pharmaceutical industry’s financial concerns have to be weighed against the reality that most recipients of recycled drugs wouldn’t be able to afford the drugs in the first place, Mac-Cormick notes.

He adds that the industry would also risk public approbation by opposing drug recycling programs. De facto, they’d be saying: “‘Yeah our drug works; we just don’t want anyone to have it who would get it for free.’ No one would say that, I don’t think.”

Not all firms appear opposed. Francesco Bellini, chairman of the Laval, Quebec-based pharmaceutical firm Bellus Health Inc., for example, calls it “a noble idea.”